Abstract

Learning a language means both mastering the grammatical structures and using contextually appropriate language, or developing sociolinguistic competence, which has been examined by measuring the native-like patterns of sociolinguistic variables. This study investigates subject personal pronoun expression (SPE) variation in Mandarin by young adult and child heritage language learners (or Chinese Heritage Language, CHL) and explores the development of sociolinguistic competence. With data collected from 15 young adults and 27 children, regression analyses show that internal linguistic constraints, psychophysiological constraints, and social constraints all significantly affect SPE variation in CHL. Overall, CHL children used fewer subject pronouns than young adults. The use of pronouns in both child language and young adult speech is constrained by similar factors. However, the difference in SPE patterns between the two groups was not statistically significant. This suggests that children may have already established some adult-like variation patterns, but these are not further developed until early adulthood. By exploring the development of sociolinguistic competence, this research contributes to the current understanding of how sociolinguistic variables are acquired and employed in heritage language at different developmental stages.

1. Introduction

Learning a language means not only mastering the grammatical structures of a target language but also becoming a legitimate member of the target speech community. It requires knowledge about how to recognize and produce contextually appropriate language, or sociolinguistic competence, which has been examined by measuring the native-like patterns of sociolinguistic variables (Bayley et al., 2022; Bayley & Regan, 2004; Lyster, 1994; Regan, 1996). Previous studies showed that besides internal grammatical constraints, external factors, including age, gender, language proficiency, and language contact (e.g., studying abroad), may all affect learners’ choice of different linguistic variants (Edwards, 2011; Eisenstein, 1982; Kennedy Terry, 2022; Pozzi, 2022; Preston & Bayley, 1996; Regan et al., 2009; Romaine, 2003). However, language learning often differs between typical L2 learners and heritage language learners due to input, language environment, and learner background. It may be reasonable to suspect that these factors also contribute to the development of sociolinguistic competence. This study investigates the subject personal pronoun expression (SPE) variation in Mandarin by young adult and child Chinese Heritage Language (CHL) learners and explores the development of sociolinguistic competence in early childhood and early adulthood. With spontaneous speech data collected from 15 young adults and 27 children, regression analyses show that internal linguistic constraints, psychophysiological constraints, and social constraints all significantly affect SPE variation in CHL. By exploring variation acquisition and the development of sociolinguistic competence in heritage language, this research contributes to the current understanding of how sociolinguistic variables are acquired and employed by heritage language learners at different developmental stages.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sociolinguistic Competence and the Use of Sociolinguistic Variables

The development of sociolinguistic competence, or the ability to use the target language appropriately in various contexts as an active interlocutor with native speakers, differs in first language (L1), second language (L2), and heritage language (e.g., Bayley & Regan, 2004; Dewaele, 2004; Holmes & Brown, 1976; Lyster, 1994; Mede & Dikilitaş, 2015; Mougeon et al., 2010; Nagy et al., 2011; Regan, 1996; Regan et al., 2009; Van Compernolle & Williams, 2012; Young & Lee, 2004; Yu, 2005; X. Zhang, 2021). In L1, children gradually acquire sociolinguistic patterns via interactions with more experienced community members (Holmes & Brown, 1976; Roberts, 1997; Smith & Durham, 2019). Labov (1989) argues that before all the basic grammatical rules have been fully acquired, children begin to learn constraints on sociolinguistic variables. However, this is more challenging for L2 learners who often lack resources to acquire native-like patterns. Early studies on L2 French use in Montreal have revealed that when L2 learners had close interactions with native speakers, they were able to use the vernacular variants in near-native ways (Nagy et al., 2003; Sankoff et al., 1997). However, for classroom L2 students, this is much more difficult, as only limited types of language input can be provided. For example, Mougeon et al. (2010) illustrated that high school French immersion students tended to overuse formal linguistic variants, and this may be attributed to the underuse of colloquial variants in pedagogical materials and teachers’ speech. For heritage language learners, it depends on how the heritage language has been acquired and maintained (or not maintained). Only a few scholars have explored how heritage language learners acquire and develop sociolinguistic patterns. Representative works by Nagy (2015) and Nagy et al. (2011) examined several heritage languages, including Cantonese, Italian, Russian, and Ukrainian spoken in Toronto. The results revealed cross-generational differences in Voice Onset Time (VOT), but not in subject pronoun use, and both variables were not related to language contact, use, or attitudes.

Two fundamental aspects of sociolinguistic competence have been discussed: the interpretation of the sociocultural context in which the conversation occurs and the appropriate use of the language (Van Compernolle & Williams, 2012). From a variationist perspective, this has been mainly examined by analyzing variation patterns in a particular sociolinguistic variable, such as ne deletion in French (Dewaele, 2004; Regan, 1996). The following sections review previous studies on SPE, which is a widely examined sociolinguistic variable across languages and the one that the current study investigates.

2.2. Constraints and Patterns in Subject Pronoun Variation: Adult Language

Pronominal subject variation has been widely explored in many languages, including Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Persian, Chinese, and German, among others (e.g., Barbosa et al., 2005; Barrenechea & Alonso, 1973; Bayley & Pease-Alvarez, 1997; Beaman, 2024; Bohnacker, 2013; Cameron & Flores-Ferrán, 2004; Kato & Duarte, 2021; X. Li et al., 2012; Nagy et al., 2011; Nanbakhsh, 2011; Otheguy & Zentella, 2012; Paredes Silva, 1993; X. Zhang, 2021). In these pro-drop languages where a grammatical subject is eligible to be unexpressed, the overt expression of a subject pronoun is not always required. As shown in the following examples in Chinese Mandarin, the subject “frog” can be expressed with a noun phrase, a subject pronoun, or be unexpressed. In this case, the subject pronoun is optional and, to some extent, can reflect the speaker’s sociolinguistic competence: the absence of pronoun in some cases may cause misunderstanding, while the overuse of pronoun may sound inappropriate.

| Sentence (1) | |||||||||||

| Qīngwā | kànjiàn | nàge | chuán, | tā | jiù | zhǔnbèi | tiào | dào | nàge | chuán | shàng |

| 青蛙 | 看见 | 那个 | 船, | 他 | 就 | 准备 | 跳 | 到 | 那个 | 船 | 上。 |

| frog | see | that | boat | 3sg | just | prepare | jump | to | that | boat | on |

| ‘The frog saw that boat, he was preparing to jump on that boat’. | |||||||||||

| Sentence (2) | |||||||||||

| Qīngwā | kànjiàn | nàge | chuán, | jiù | zhǔnbèi | tiào | dào | nàge | chuán | shàng | |

| 青蛙 | 看见 | 那个 | 船, | ∅ | 就 | 准备 | 跳 | 到 | 那个 | 船 | 上。 |

| frog | see | that | boat | ∅ | just | prepare | jump | to | that | boat | on |

| ‘The frog saw that boat, ∅ was preparing to jump on that boat’. | |||||||||||

Following the variationist approach, most of the SPE investigations have been based on spontaneous speech collected from adult language users. Previous research has shown how native SPE variation is constrained by various factors and to what extent L2 and/or heritage learners diverge from native speakers. Pioneered by Barrenechea and Alonso (1973) who explored Spanish personal pronoun use in Buenos Aires, L1 research has revealed that, as observed in other sociolinguistic variables, SPE variation is not random but is systematically constrained by internal linguistic, psychophysiological, and social factors (Erker et al., in press). However, to what extent L2 and/or heritage language learners can acquire the native-like patterns depends on learners’ L1 background, the learning environment, and L2 proficiency, among other factors. For example, in an early study that investigated pronoun use by Japanese and English learners of Mandarin, Polio (1995) found that L2 learners employed fewer unexpressed forms compared to native speakers, and pronoun absence increased with their Mandarin proficiency. Furthermore, Japanese students used more unexpressed pronouns than their English counterparts. This discrepancy could partially be attributed to the influence of structural transfer, given that Japanese lacks genuine third-person pronouns and relies on classifier constructions to replace pronouns. The study by X. Li (2014) resonated with these findings: learners whose L1s were languages where subject pronouns are less frequently dropped (e.g., English and Russian) used more overt pronouns than learners whose L1s often allow unexpressed pronouns (e.g., Korean and Japanese); and lower-proficiency learners across language groups used more overt pronouns. For SPE variation in heritage languages, Nagy et al. (2011) analyzed subject pronoun use in three heritage languages (Cantonese, Italian, and Russian) and English in Toronto. No significant difference was identified across generations, suggesting that SPE was not undergoing change in any of these communities. In addition, X. Zhang (2021) revealed that Mandarin heritage students largely used the SPE patterns found in classroom input, and students who had spent their early childhood in Mandarin-speaking regions (e.g., mainland China and Taiwan) significantly employed fewer overt subject pronouns (56%) than their US-born peers (83%).

Besides the discrepancy in SPE patterns between native speakers and L2/heritage learners, SPE variation is found to be consistently constrained by internal linguistic factors or the structural features of the variation envelope, psychophysiological factors or cognitive conditions, and social factors or social characteristics of the speakers and contexts (Otheguy & Zentella, 2012). Firstly, linguistic constraints that have been frequently investigated by previous studies concern morphosyntactic aspects of the subject, verb form, and clause type (Erker et al., in press). For example, person and number of the subject have emerged cross-linguistically as strong linguistic constraints in predicting pronoun use (e.g., Bouchard, 2018; Cameron & Flores-Ferrán, 2004; Jia & Bayley, 2002; X. Li et al., 2012; X. Li & Bayley, 2018; Otheguy & Zentella, 2012; X. Zhang, 2021). Secondly, psychophysiological constraints such as referential continuity (or switch in subject referent) and priming have been shown as significant conditioning factors: a subject pronoun tends to be unexpressed if it repeats the same referent that has been mentioned in the preceding clause (Azar & Özyürek, 2015; Bayley & Pease-Alvarez, 1996; Bouchard, 2018; X. Li & Bayley, 2018; Shin & Otheguy, 2009; Tamminga et al., 2016; X. Zhang, 2021). Thirdly, the effects of social constraints are more community-specific, depending on who the interlocutors are and the particular characteristics of the contexts. For example, females tended to use more subject pronouns in L1 Mandarin, but this gender differentiation was not identified in L2 Mandarin or heritage Mandarin (X. Li et al., 2012; X. Li, 2014; X. Zhang, 2021).

2.3. Constraints and Patterns in Subject Pronoun Variation: Child Language

While SPE variation has been widely explored as a sociolinguistic variable in adult speech, it has been mainly interpreted from the developmental perspective for child language. Around the age of one to two, children begin to combine single words and form sentences (Clark, 2016; Erbaugh, 1982). Subject-missing sentences, such as “hug mommy” instead of “Lillian/I hug mommy,” are typical in early child language cross-linguistically, even in non-pro-drop languages such as English (P. Bloom, 1990; Guasti, 2002). Empirical studies have identified subject drop in English (Hyams, 1983; Hyams & Wexler, 1993), Mandarin (Wang et al., 1992), Cantonese (Lee, 1997), Italian (Valian, 1991), Brazilian Portuguese (Valian & Eisenberg, 1996), Korean (Kim, 2000), and Japanese (Nakayama, 1996) by children under the age of five. In general, young children use fewer subjects than adults and may drop up to 30% of the subjects even in English, Dutch, or French where subjects are obligatory (Clark, 2009, p. 204). However, their overt subject expression increases with age and quickly reaches the adult level (Kim, 2000). It was found that personal pronouns first appear in native Mandarin child language by the end of the second year (Hsu, 1987; Y. Li, 1995; Xu & Min, 1992), and children seemed able to use unexpressed pronouns at about the age of two to three in their two-word stage (Chao, 1973; Erbaugh, 1982; Zhu et al., 1986).

Due to the unique patterns of language development, pronominal subject variation in child language has been found to be significantly affected by processing capability, which increases with children’s age, while linguistic and social constraints also play a role, as found in adult language. For psychophysiological effects, findings are inconsistent. As the processing hypothesis proposes, P. Bloom (1990) found that lexical subjects with the most phonetic length led to the heaviest processing load, followed by pronouns, then unexpressed subjects. However, Hyams (1983, 1986) demonstrated that children who produced subject-absent sentences were also capable of producing longer utterances. On the other hand, as children gradually develop their native language and acquire the communicative rules in their speech community, their language variation patterns become more similar to adult patterns. For example, Shin and Cairns (2012) found that Spanish-learning children could not perform as well as native adults in SPE usage at five years of age, but exhibited sensitivity to referent continuity at the age of eight and were able to deal with unexpressed pronouns appropriately. Linguistic constraints seem to be more language-specific in SPE variation: unexpressed pronouns were more frequently employed in pro-drop languages such as Mandarin, Spanish, or Portuguese than in non-pro-drop languages such as English by monolingual children aged two to five (Sorace et al., 2009; Wang et al., 1992). Some strong social constraints, such as gender, can sometimes be observed in SPE patterns among older children. For instance, as female adults often tend to use more pronouns than their male counterparts, girls are also found to prefer overt pronouns more than boys. This gender differentiation did not appear statistically significant among Spanish-speaking children aged under eight from Mexico (Shin, 2012), but it had a strong effect on Spanish SPE variation among children aged ten to twelve in California (Bayley & Pease-Alvarez, 1996, 1997).

2.4. The Current Study

This study explores an aspect of sociolinguistic competence among CHL children and young adult speakers. Heritage language speakers, who usually have been exposed to their heritage languages from birth at home, often outperform non-heritage peers in communication and comprehension (Weger-Guntharp, 2006; Xiao, 2006). However, limited home input and the lack of formal language instruction can hinder their full language development and sociolinguistic competence (Kondo-Brown, 2001; Kondo-Brown & Brown, 2017). Although heritage language research has been emerging, longitudinal and cross-sectional studies on heritage language development, especially sociolinguistic skills, are still rare. By comparing subject pronoun use by CHL children and young adults, this study examines the development of sociolinguistic competence in CHL and the extent to which it is influenced by internal linguistic, psychophysiological, and external social factors. Based on the theories of variation acquisition and previous findings on SPE variation, three hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1:

As subject absence is a typical feature in early grammar (Clark, 2009; Hyams & Wexler, 1993), subject pronouns will be dropped more in child language than in young adult speech. And because young children are not as grammatically competent as adults (L. Bloom et al., 1975; Chomsky, 1964; Miller & Ervin, 1964; Solan, 1983), their SPE patterns may be constrained by fewer conditioning factors than those of young adults.

Hypothesis 2:

Children could show sensitivity to SPE variation at a young age (Shin, 2012; Shin & Cairns, 2012), and this knowledge may be maintained but not further developed until early adulthood due to the limited input of heritage language (Duff et al., 2017; Xiao, 2010). Thus, young adults may demonstrate similar SPE patterns to what is observed in child language.

Hypothesis 3:

Children tend to use more subject pronouns than young adults, and their SPE patterns are constrained by more factors. This may be associated with crosslinguistic transfer in bilingual children’s language development (Liceras & Fernández Fuertes, 2019; Qi, 2010; Serratrice, 2007; Sorace et al., 2009): in the early stages of Mandarin–English bilingual development, children might transfer the English non-pro-drop structure into CHL, leading to a higher frequency of subject pronouns in Mandarin. As young adults have more experience with pro-drop structures as a language-specific feature in CHL, they may use fewer pronouns in Mandarin.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

In the school years, 2021–2023, spontaneous speech data were collected from 27 children (12 girls, 15 boys, aged 3;01–5;09) from two English–Mandarin dual immersion preschools in Northern California. All children were CHL learners with at least one parent or grandparent who was a native speaker of a Chinese language. All families belonged to the middle class, and all parents had received bachelor’s or higher degrees. The preschools adopted both English and Mandarin for instruction in a 50:50 ratio. Mandarin teachers, most of whom were native speakers, were responsible for providing Mandarin language input in class. Most children used 50% or more Mandarin along with English or other Chinese dialects (e.g., Taiwanese or Shanghainese) at home. Family information, including demographic background and home language practice, was collected via a family background questionnaire. Language practice in school, teacher–child communication, and peer interaction were recorded in field notes via about 300 h of classroom observation. At the beginning (time 1) and the end (time 2) of the school years, children completed several language tasks, including a Mandarin version of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 5 (Chow & McBride-Chang, 2003; Lu & Liu, 1998; D. Zhang, 2017), the Woodcock–Johnson IV Oral Language for English oral communication skills (Schrank & Wendling, 2018), a story-retelling task of a frog story (Mayer, 1969), and a casual conversation in which the child was encouraged to talk about their personal experiences such as weekend activities, favorite friends at school, and animals at zoo. All language tasks were conducted in Mandarin, except for the English language assessments.

Young adult language data were collected from 15 CHL undergraduate students (11 females, 4 males, aged 18–27) who self-identified as CHL learners. All of them enrolled in the “heritage student track” for Chinese learning at a research university in Northern California. All students were from Chinese immigrant families: they either were born in the United States or arrived with their families in the United States around the age of four or five. They used Mandarin or other varieties (e.g., Taiwanese, Cantonese, or Chaoshan dialect) at home with their parents and grandparents, but not with siblings. Formal Chinese education was usually interrupted or even absent, and family education was not enough to support their Chinese literacy development. Spontaneous data were elicited via sociolinguistic interviews (25–35 min) in Mandarin. The conversations dealt with family background, language learning experience, daily life, and opinions about Chinese varieties, after which students watched the wordless Pear Story film and retold the story in Mandarin (Chafe, 1980).

The participants’ demographic and language backgrounds can be found in the appendices (Appendix A for children and Appendix B for young adults). All speech data were audio-recorded with a Sony ICD-UX570 Digital Voice recorder with a Lavalier lapel microphone at a 44.1 kHz sampling rate. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim in ELAN (ELAN, 2024).

3.2. Data Coding

With text transcriptions, the use of SPE in each clause was coded for its internal linguistic constraints, psychophysiological constraints, and socio-stylistic constraints following the variation conditioning schema proposed by Tamminga et al. (2016). Specifically, internal linguistic constraints (i-conditioning) are structural conditioning factors, such as person and number of the subject and clause type; psychophysiological constraints (p-conditioning) deal with cognitive conditioning factors including referential continuity and structural priming; and socio-stylistic constraints (s-conditioning) involve social characteristics of the context or the speaker, such as discourse type, age, gender, regional origin, and heritage generation.

3.2.1. I-Conditioning: Person and Number

Many studies across languages have shown that speakers are sensitive to person and number of the subject when they choose between a present or absent subject pronoun (e.g., Barrenechea & Alonso, 1973; Bayley et al., 2017; Bayley & Pease-Alvarez, 1997; Bohnacker, 2013; Cooper & Engdahl, 1989; Flores-Ferrán, 2007; Haag-Merz, 1996; McKee et al., 2011; Otheguy & Zentella, 2012; Rosenkvist, 2018; Wulf et al., 2002). Although Chinese is a non-inflectional language, the effect of person and number on SPE is still consistent and significant, as previous research revealed (Jia & Bayley, 2002; X. Li et al., 2012; X. Li & Bayley, 2018; X. Zhang, 2021). In this factor group, six categories were coded: first-person, second-person, and third-person singulars and plurals.

3.2.2. I-Conditioning: Clause Type

Prior findings in Spanish and Mandarin by Carvalho and Bessett (2015), X. Li and Bayley (2018), Nagy (2015), Orozco (2015), and Otheguy and Zentella (2012) demonstrated that clause type is another significant linguistic factor for SPE. Following their models, clause type was coded as main, subordinate (e.g., relatives, complementizers, etc.), and other (e.g., imperatives, etc.).

3.2.3. P-Conditioning: Referent Continuity

Many studies have shown that when the referent is mentioned in the same form as in the preceding clause, an absent pronoun is often preferred by speakers (Cameron, 1992, 1993, 1995; Carvalho et al., 2015; Erker & Guy, 2012; X. Li et al., 2012; X. Li & Bayley, 2018; Otheguy & Zentella, 2012; X. Zhang, 2021, etc.). Thus, referent continuity or a switch in reference from the preceding finite verb was coded as same when the previous clause contained the same subject referent as the current one and different when the referent was switched.

3.2.4. P-Conditioning: Priming

Priming, or the non-conscious tendency to repeat some structural aspect that occurs in a previous utterance, has been found to be a powerful influencing factor in language use, language development, and language change (Bock, 1986; Mahowald et al., 2016; Pickering & Garrod, 2017). For SPE variation, priming is also a significant predictor as “unexpressed subjects tend to be followed by unexpressed subjects, while preceding pronouns favor subsequent pronouns” (Torres Cacoullos & Travis, 2016, p. 733). In this study, priming was coded as pro_present if the preceding subject was expressed as a pronoun, pro_absent if the preceding subject was a pronoun but unexpressed, lexical_np if the preceding subject was expressed as a lexical noun phrase, and n/a if the subject was not available in the preceding clause.

3.2.5. S-Conditioning: Discourse Type

Previous studies showed that discourse type (e.g., classroom speech, telephone conversation, narration, or sociolinguistic interview) or the pragmatic characteristics of a particular register, such as formality, may affect speakers’ choices of SPE in Mandarin (Jia & Bayley, 2002; X. Li & Bayley, 2018; X. Zhang, 2021). Regarding the speech content in CHL child and young adult speech, discourse type was coded as casual for sociolinguistic interviews, narrative for storytelling or story-retelling, and test for language assessment (child language only).

3.2.6. S-Conditioning: Age, Gender, Regional Origin, Test, and Heritage Generation

Social characteristics of the speakers that were coded included age (numerical), gender (female, male), regional origin (child language only), test (child language only), and heritage generation (young adult language only). Regional origin categorized the birthplaces of the parents: whether they were born in mainland China or Hong Kong and Taiwan. According to the time and language tasks children were asked to do, the test coded the context of the token in another form. For example, test CHN1 means the data were collected at the beginning of the school year with Chinese language assessments. Heritage generation was coded as early-arrival for those who migrated to the United States around age of four or five and US-born for those who were born in the United States.

3.3. Data Analysis

To examine the SPE variation in CHL child and young adult language, generalized linear mixed-effects models were adopted to model the binary outcome of the presence or absence of a subject personal pronoun based on conditioning factors as described above. To control for individual variation, the individual speaker was set as a random effect (Baayen, 2008). Three models were adopted: model 1 examined the SPE variation in child language, model 2 examined the SPE variation in young adult language, and model 3 examined whether the SPE variation in child language and young adult language differed significantly. All the statistical models were implemented in R with the glmer() function in the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015).

4. Results

In total, 5238 tokens of SPE were elicited from child language, and, 5565 tokens were elicited from young adult language, after a few factor groups had been excluded. Following the coding scheme by X. Li and Bayley (2018), tokens in false starts, repeated clauses, formulaic expressions (e.g., 谢谢 ‘thank you’), and serial verbal constructions (e.g., 我不喜欢放在这里 ‘I don’t like to put (it) here’) have been excluded. In addition, to avoid extreme or unreliable coefficient values that may have been caused by few tokens in a factor (Johnson, 2009), second-person plurals (3 or 0.04% in child language and 4 or 0.07% in young adult language) were excluded. The tokens that occurred during language tasks in child language were also excluded as there was no comparable context in young adult speech. Corresponding token numbers and SPE rates of each factor are listed in Table 1. The overall SPE rate in child language reached 69.76%, which was slightly lower than the overall SPE rate of 70.73% in young adult language. Both were higher than the SPE rate of native speakers: 53% for teachers, students, and university administrators (aged 19–73) in telephone conversations (Jia & Bayley, 2002), 47.2% for teachers and students (aged 18–65) in conversation and narration (X. Li et al., 2012), and 65.7–69.8% for interlocutors (various occupations, aged 14–63) in sociolinguistic interviews (Erker et al., in press). The variation in SPE rates may be attributed to the social characteristics of the interlocutors and contexts, style differences, or dialectal differences.

Table 1.

Data summary.

4.1. SPE Patterns in CHL Child Language

As shown in Table 2, the regression results of SPE patterns in child language reveal that the i-conditioning factor of clause type, the p-conditioning factors of referent continuity and priming, and the s-conditioning factors of discourse type, age, and test were all significant constraints on pronoun usage by children. Specifically, for internal linguistic constraints, children favored the presence of subject personal pronouns in subordinate clauses (β = 0.673, p < 0.001). For psychophysiological constraints, the same referent continuity favored the unexpressed pronoun use (β = −0.190, p = 0.025). Priming effect was also significant: when the pronoun was absent in the preceding clause, the pronoun in the current clause tended to be absent (β = −0.333, p = 0.004); when the pronoun was present in the previous clause, the current pronoun tended to be expressed (β = 0.668, p < 0.001). For social constraints, SPE used in narration was unexpressed more than SPE in casual speech (β = −0.338, p < 0.001). In addition, children significantly used more expressed pronouns in the first English assessment (β = 0.462, p < 0.001), and their pronoun use increased with age (β = 0.537, p = 0.004). Besides these constraints, person and number, regional origin, and gender did not reach significance in this model.

Table 2.

SPE variation in child language 1.

4.2. SPE Patterns in CHL Young Adult Language

Table 3 lists the results of the regression analysis of SPE variation in young adult language. As shown below, the i-conditioning factor of person and number, the p-conditioning factors of referent continuity and priming, and the s-conditioning factors of discourse type, heritage generation, gender, and age appeared to be significant predictors. Specifically, for internal linguistic constraints, all singular pronouns and third-person plural 他们 ‘they’ tended to be overtly expressed (s1 β = 1.033, p < 0.001; s2 β = 1.000, p < 0.001; s3 β = 0.909, p < 0.001; p3 β = 0.784, p < 0.001). The other linguistic constraint, clause type, did not reach significance in this model. For psychophysiological constraints, again, the same referent continuity favored the use of unexpressed pronouns (β = −1.273, p < 0.001). Priming was still significant, but in a slightly different way: young adults preferred unexpressed subject personal pronouns when the subject pronoun in the preceding clause was absent (β = −0.542, p < 0.001) or when the subject in the preceding clause was not available in the structure (β = −0.425, p = 0.012). Lastly, for social constraints, compared with other discourse types, narration appeared to be a favorable environment for absent subject pronouns (β = −0.464, p < 0.001). Additionally, young adults who were born in the United States preferred to use more pronouns than their early-arrival counterparts (β = 1.069, p < 0.001). Males in general used fewer pronouns than females (β = −0.765, p = 0.017), and, as found in child language, older adults tended to use more pronouns (β = 0.157, p = 0.012).

Table 3.

SPE variation in young adult language 1.

4.3. Insignificant Group Difference

To examine whether the SPE patterns differed significantly between children and young adults, model 3 tested SPE variation in both child and young adult language with group-specific factors (i.e., test, heritage generation, and regional origin) removed. As shown in Table 4, the same constraints were found in child language and young adult language: i-conditioning factors including person and number, p-conditioning factors including referent continuity and priming, and the s-conditioning factor of discourse type. However, group (children versus young adults) did not reach significance in this model, which indicates that the two groups of speakers did not differ significantly in their SPE patterns (for young adults, β = 0.174, p = 0.452). When group was set as the only fixed effect in the model, the group difference was still not statistically significant (for young adults, β = 0.188, p = 0.395).

Table 4.

SPE variation in child and young adult language 1.

5. Discussion

5.1. Linguistic Internal Constraints

Linguistic structural factors such as phonological environment or grammatical rule often shape the envelope of variation in which a particular sociolinguistic feature can vary in a few forms. Variation in the use of personal pronouns is common historically and dialectically in Chinese. A larger number of personal pronouns was present in early and middle Chinese compared to modern Chinese (Hong, 2020; Jiang & Ren, 2023). Absent subject pronouns have been identified in classical, middle, and modern Chinese. Overall, it seems that the types of subject pronouns have reduced, whereas the overall use of subject pronouns has increased from Old Chinese to Modern Chinese (e.g., Dong, 2005; Tang, 1996). There is, however, no evidence to determine whether this is a cross-regional or cross-dialectal language change. For linguistic conditioning factors of Chinese SPE variation, previous studies showed that person and number, clause type, animacy, referent specificity, and verb type have significant impacts on variable use (Jia & Bayley, 2002; X. Li et al., 2012; X. Li & Bayley, 2018; Nagy et al., 2011; X. Zhang, 2021). In this study, regression analyses showed that person and number were powerful predictors of SPE variation in young adult speech, while clause type had a significant influence on SPE in child language.

For person and number, results (see Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4) demonstrate that in young adult speech, all singular forms and third-person plural forms were preferred to be expressed. Only first-person plurals 我们 ‘we’ were more unexpressed when the pronoun was used to refer to the speaker and their family members or classmates as a group. Child language showed the same person and number constraint pattern, though the results were not statistically significant. The correlation between singularity and pronoun expression echoes previous findings in Mandarin speech by native adult speakers (Jia & Bayley, 2002; X. Li et al., 2012). The differences in person and number constraints on SPE in child and young adult language suggest that at the age of four or five, children may not have reached a native-adult-like SPE pattern regarding the singularity preference. Young adults, on the other hand, performed similarly to native speakers for this linguistic constraint.

Clause type only reached significance in child language: children expressed more pronouns (84.77%) in subordinate clauses, such as 那是我选的 ‘that is what I chose’. Based on this result, it may be reasonable to suspect that the highly frequent use of pronouns in subordinate clauses is to avoid reference ambiguity as Chinese lacks inflectional markers, and the interpretation of unexpressed pronouns mainly relies on discourse clues. However, young adults did not seem to be sensitive to this linguistic difference. They demonstrated similar SPE usage patterns in all clause types and did not emphasize the pronoun in a complex sentence structure where a misunderstanding of the referent was possible. Previous findings show that compared to imperatives, native Mandarin speakers tended to express more pronouns in statements and questions (Jia & Bayley, 2002; X. Li et al., 2012). However, due to the sociolinguistic characteristics of CHL speech, declarative clauses occurred much more often than other clause types (>95%) and may have caused skewed results in statistical analyses. In this case, L1 findings cannot be compared as a baseline.

5.2. Psychophysiological Constraints

Sociolinguistic research has traditionally categorized constraints on variation into linguistic and social factors. Psychophysiological factors, as mentioned by Tamminga et al. (2016), are concerned more with how variables are processed cognitively and affected by articulation/perception characteristics. As regression results show, SPE in CHL was significantly affected by two p-conditioning factors: referent continuity and priming. Overall, the p-conditioning factors appeared to be consistent in both child and young adult speech.

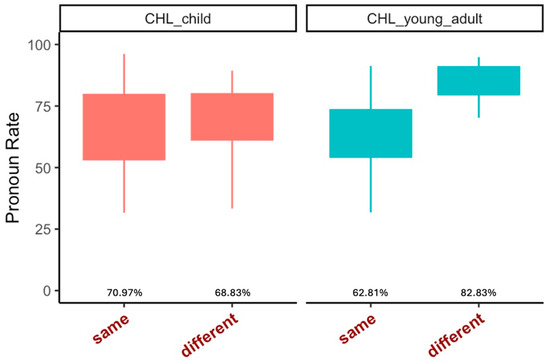

When language is used in a conversation, the listener and the talker often need to track and hold the referents that have been mentioned in the conversation in short-term memory via linguistic signs (Azar & Özyürek, 2015; Contemori & Dussias, 2016; Davidson, 1996; Nieuwland et al., 2007). For SPE, referent continuity, sometimes called coreference in previous studies, plays a key role in completing this task. As many studies have revealed, when a referent is the subject of the preceding clause, the speaker tends not to use a pronoun for the same referent again (Jia & Bayley, 2002; X. Li et al., 2012; X. Li & Bayley, 2018; Nagy, 2015; X. Zhang, 2021). The referent continuity effect was consistent in both child language and young adult speech (see Table 2 and Table 3 and Figure 1). Although the average SPE rate for the same referent (70.97%) was slightly higher than the rate for a different referent (68.83%) in child language, regression analysis indicates that referential continuity is a favorable environment for unexpressed pronouns. Echoing previous findings, speakers favored unexpressed pronouns when the same referent had been mentioned in the preceding clause. Though Shin and Cairns (2012) found that Spanish monolingual children were not as sensitive as native adults to referent continuity until age eight, CHL children appeared to become native-like regarding this p-conditioning feature around the age of four or five. If this is earlier than Chinese native children (no empirical evidence to date), then language contact or the bilingual environment may facilitate an early establishment of sociolinguistic patterns.

Figure 1.

SPE across referent continuity.

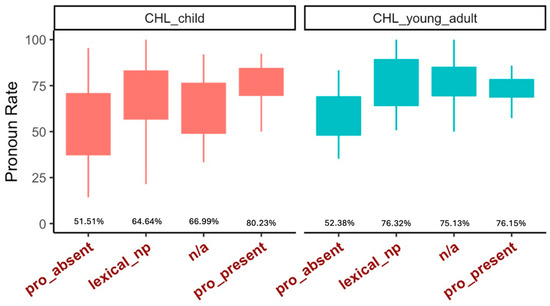

There is substantial evidence indicating that language users tend to repeat structures that have been recently used (Bock, 1986; Branigan et al., 2000; Hartsuiker et al., 2004). This priming effect has also been found in the use of subject pronominal variation (Tamminga et al., 2016; Travis, 2007). SPE variation in CHL data was also significantly affected by priming. Specifically, children tended to omit the pronoun when the previous one was absent (SPE rate = 51.51%, see Figure 2) and preferred to express the pronoun when the previous one was present (SPE rate = 80.23%). Similarly, the absence of the preceding pronoun favored the unexpressed pronoun in young adult speech (SPE rate = 52.38%).

Figure 2.

SPE across priming.

5.3. Social Constraints

In variationist research, the analysis of social factors affecting speakers’ choices among variable forms constitutes one of the key areas for investigation as it reveals the social meanings behind the sociolinguistic variables and what they might index in a given speech community (Eckert, 2012; Labov, 1972). In the examination of SPE in CHL speech, it was found that discourse type and age are significant social constraints in both child and young adult language, and heritage generation and gender—only in young adult speech.

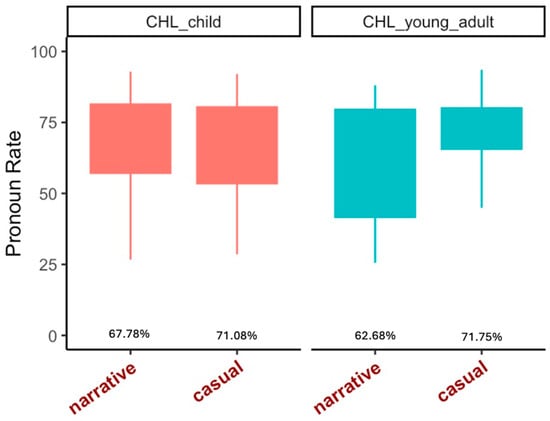

Discourse type was shown to be a strong predictor of SPE patterns in previous studies, although different discourse types were examined (e.g., telephone conversation, classroom instruction, storytelling, casual interaction, or sociolinguistic interview) (Jia & Bayley, 2002; X. Li & Bayley, 2018; X. Zhang, 2021). For CHL data, all children and young adults were recorded in a private and quiet classroom, which provided a relaxing context for interacting with the researcher. In this case, both children and young adults significantly reduced their use of subject pronouns in narration when there were extensive descriptions of sequential actions involving the same referent (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

SPE across discourse type.

Moreover, older children tended to use more pronouns in their utterances. The same age effect was also found in young adult language. It is possible that with the exposure to English increased, children’s SPE patterns in their heritage language were influenced. As English always requires an expressed subject, speakers may transfer this feature into Chinese and use more pronouns on subject positions. The high SPE rates in English assessments (71.29% and 71.63%) in child language can also be attributed to the language contact effect. This has been identified in Spanish SPE variation in child language as well: while Spanish monolingual Mexican children (aged 6;4–7;8) overtly expressed SPE at a rate of 6.3%, Spanish–English bilingual children in California (aged over 8) had a higher SPE rate of around 20–24% (Shin, 2012).

In addition, heritage generation and gender also strongly affected how subject pronouns were used by young adults. Specifically, speakers who were born in the United States, compared to their peers who spent four or five years living in mainland China or Taiwan, used significantly more subject pronouns (78.52% vs. 60.19%) in their speech. This provides more evidence to support the assumption that SPE patterns in heritage language could be affected by language contact with English. Moreover, males favored unexpressed pronouns significantly more than females. This gender difference whereby males tend to use the vernacular variant has been identified in SPE variation in child Spanish (Bayley & Pease-Alvarez, 1996, 1997), adult Mandarin (X. Li et al., 2012), and the use of other variables (Cameron, 2010; Holmquist, 2008; Roberts, 1997). In CHL child language, boys tended to use fewer pronouns than girls, but this was not statistically significant. It seems that children are not sensitive to how adults use the variable according to their gender roles in early childhood as gender differences emerge and increase during elementary school, then peak in adolescence (Cameron, 2010).

5.4. Group Differences

By comparing the SPE patterns in child and young adult speech, results show that (1) the i-conditioning factor of person and number, (2) both p-conditioning factors, including referent continuity and priming, and (3) discourse type and age among s-conditioning factors significantly constrain SPE variation in child and young adult language. This may suggest that compared to linguistic and social constraints, psychophysiological factors are more powerful predictors with consistent effects on SPE patterns. However, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant. These findings align with what hypothesis 2 proposes: in early childhood, children may have already established some adult-like variation patterns, and these patterns or the corresponding sociolinguistic competence could be maintained but would not be further developed with limited language input until early adulthood. To determine whether the observed SPE patterns in CHL have reached a native-adult level, further investigations comparing data from native and heritage speakers are required.

6. Conclusions

By investigating the use of subject pronoun as a sociolinguistic variable in CHL, this study explored the development of sociolinguistic competence in early childhood and early adulthood between which the formal instruction of heritage language was largely interrupted and the use of heritage language was limited. Regression statistics show that linguistic, psychophysiological, and social constraints all significantly affect the use of subject personal pronouns by CHL children and young adults. Among all the tested factors, the i-conditioning factor of person and number, the p-conditioning factors of referent continuity and priming, and the s-conditioning factors of discourse type and age appear to be strong predictors. In addition, by comparing the pronoun use in child and young adult speech, the results reveal that the difference of SPE patterns between cohort groups is not statistically significant, indicating that heritage language learners’ sociolinguistic competence regarding subject pronoun use may have not been further developed after early childhood.

The development of sociolinguistic competence regarding the acquisition of variation is an integral part of language learning (Labov, 2013; Roberts, 1997; Smith & Durham, 2019). To become a legitimate member of a local speech community, children need to learn both grammatical rules and sociolinguistic norms from more experienced community members (Bayley & Regan, 2004; Holmes & Brown, 1976; Shin, 2012). However, L2 learners and heritage language speakers have to do this in more than one language and figure out “how they [can] deploy their linguistic resources in day to day interactions in the multiple speech communities to which they belong and to which they aspire” (Bayley & Regan, 2004, p. 18). To answer these questions, future studies should address how the use of sociolinguistic features varies among different groups of speakers in various contexts. The comparison among native, heritage, and L2 speakers within and across age cohorts will be able to reveal the potential effects of dialectal difference, language contact, and the developmental trajectory of variation acquisition in detail.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of California, Davis (protocol code: 1425729-2, date of approval: 18 April 2019; protocol code: 1602628-1, date of approval: 17 June 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author due to privacy issues.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all the participants of this study, including the undergraduate students, children, parents, and teachers, for their invaluable contributions to this research. I am deeply indebted to my advisor Robert Bayley for his unwavering guidance and support. Special thanks to Gregory Guy, Aria Adli, Karen Beaman, Daniel Erker, and Rafael Orozco from whom I have learned a lot to sharpen my own approaches to examining variation patterns. I extend my appreciation to the editors and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. I also wish to thank the editors for the opportunity to contribute to this Special Issue. All errors remain mine.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

CHL children’s demographic background.

Table A1.

CHL children’s demographic background.

| Name | Gender | Age | Home Language | English Oral Level | Mandarin Vocabulary Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naomi | F | 3;01 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average | ||||

| Simon | M | 3;02 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: high |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average | ||||

| Lily | F | 3;06 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: average | ||||

| Owen | M | 3;07 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average | ||||

| Kathy | F | 3;08 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average | ||||

| Mike | M | 3;08 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: high |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: high | ||||

| Eleanor | F | 3;10 | Mandarin | Time 1: high | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: high | Time 2: average | ||||

| Luis | M | 3;11 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average | ||||

| Shane | M | 3;11 | Mandarin | Time 1: high | Time 1: low |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average | ||||

| Ben | M | 4;00 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: high |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: high | ||||

| Emily | F | 4;00 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: high |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: high | ||||

| Emma | F | 4;01 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: high | Time 2: high | ||||

| Andrew | M | 4;04 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: low |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average | ||||

| Peter | M | 4;04 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: average | ||||

| Sheldon | M | 4;06 | English, Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: low |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: low | ||||

| Tessa | F | 4;07 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: high | ||||

| Dylan | M | 4;08 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: low |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: low | ||||

| Lia | F | 4;08 | English, Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: low |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average | ||||

| Ophelia | F | 4;08 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: high |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: high | ||||

| Alice | F | 4;08 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: high | ||||

| Jay | M | 4;10 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: average | ||||

| Cameron | M | 4;11 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: high | ||||

| Julian | M | 4;11 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: high |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: high | ||||

| John | M | 4;11 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: average | ||||

| Natalie | F | 5;00 | Mandarin | Time 1: low | Time 1: high |

| Time 2: low | Time 2: high | ||||

| Mason | M | 5;09 | Mandarin | Time 1: average | Time 1: average |

| Time 2: average | Time 2: average |

Notes: All children’s names are pseudonyms. Children’s age was calculated from the beginning of the academic year when the first language tasks were completed.

Appendix B

Table A2.

CHL young adults’ demographic background.

Table A2.

CHL young adults’ demographic background.

| Name | Gender | Age | Languages (L1, L2, L3) | Age of Arrival in the U.S. | Chinese Schools/Programs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betty | F | 18 | English, Mandarin, Spanish | 0 | No |

| Tracy | F | 18 | English, Mandarin, French | 0 | No |

| Alice | F | 18 | English, Cantonese, Mandarin | 0 | Yes |

| Tina | F | 19 | English/Mandarin, French | 0 | Yes |

| Lia | F | 19 | Chaoshan dialect, English, Spanish | 0 | Yes |

| Jerry | M | 19 | Mandarin/English | 0 | Yes |

| Jolyn | F | 19 | Mandarin, English, Spanish | 4 | Yes |

| Kattie | F | 19 | English, Cantonese, Spanish | 0 | Yes |

| Melody | F | 20 | English, Mandarin/Cantonese, Spanish | 0 | Yes |

| Tim | M | 20 | Mandarin, English, Spanish | 5 | Yes |

| Nel | M | 21 | English, Mandarin | 0 | Yes |

| Anna | F | 21 | Mandarin, English, Korean | 6 | Yes |

| Cindy | F | 22 | Mandarin, English, German | 5 | Yes |

| Lynn | F | 22 | English, Mandarin | 0 | No |

| Steven | M | 27 | Mandarin, English, Japanese | 4 | No |

Notes: All names are pseudonyms. L1, L2, and L3 indicate the order in which the languages were learned. Language A/Language B means the two languages were acquired simultaneously.

References

- Azar, Z., & Özyürek, A. (2015). Discourse management: Reference tracking in speech and gesture in Turkish narratives. Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, R. H. (2008). Analyzing linguistic data: A practical introduction to statistics using. Sociolinguistic Studies, 2(3), 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P., Duarte, M. E. L., & Kato, M. A. (2005). Null subjects in European and Brazilian Portuguese. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 4(2), 11–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrenechea, A. M., & Alonso, A. (1973). Los pronombres personales sujetos en el español de Buenos Aires. In K. Karl-Hermann, & K. Rühl (Eds.), Studia Iberica: Festschrift für Hans Flasche (pp. 75–91). Francke. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, R., Greer, K. A., & Holland, C. L. (2017). Lexical frequency and morphosyntactic variation: Evidence from U.S. Spanish. Spanish in Context, 14(3), 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, R., & Pease-Alvarez, L. (1996). Null pronoun variation in Mexican-descent children’s Spanish. In J. Arnold, R. Blake, & B. Davidson (Eds.), Sociolinguistic variation: Data, theory, and analysis (pp. 85–99). Center for the Study of Language and Information. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley, R., & Pease-Alvarez, L. (1997). Null pronoun variation in Mexican-descent children’s narrative discourse. Language Variation and Change, 9(3), 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, R., Preston, D. R., & Li, X. (Eds.). (2022). Variation in second and heritage languages: Crosslinguistic perspectives (Vol. 28). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, R., & Regan, V. (2004). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence: Acquiring sociolinguistic competence. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 8(3), 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaman, K. V. (2024). Language change in real- and apparent-time: Coherence in the individual and the community (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, L., Miller, P., & Hood, L. (1975). Variation and reduction as aspects of competence in language development. In A. Pick (Ed.), The 1974 Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, P. (1990). Subjectless sentences in child language. Linguistic Inquiry, 21, 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, J. K. (1986). Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology, 18(3), 355–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnacker, U. (2013). Null subjects in Swabian. Studia Linguistica, 67(3), 257–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, M.-E. (2018). Subject pronoun expression in Santomean Portuguese. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branigan, H. P., Pickering, M. J., Stewart, A. J., & Mclean, J. F. (2000). Syntactic priming in spoken production: Linguistic and temporal interference. Memory and Cognition, 28(8), 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R. (1992). Pronominal and null subject variation in Spanish: Constraints, dialects, and functional compensation [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, R. (1993). Ambiguous agreement, functional compensation, and nonspecific tú in the Spanish of San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Madrid, Spain. Language Variation and Change, 5(3), 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R. (1995). The scope and limits of switch reference as a constraint on pronominal subject expression. Hispanic Linguistics, 6(7), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, R. (2010). Growing up and apart: Gender divergences in a Chicagoland elementary school. Language Variation and Change, 22(2), 279–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R., & Flores-Ferrán, N. (2004). Perseveration of subject expression across regional dialects of Spanish. Spanish in Context, 1(1), 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. M., & Bessett, R. (2015). Subject pronoun expression in Spanish in contact with Portuguese. In A. M. Carvalho, R. Orozco, & N. L. Shin (Eds.), Subject pronoun expression in Spanish (pp. 143–165). Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A. M., Orozco, R., & Shin, N. L. (2015). Subject pronoun expression in Spanish. Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, W. L. (1980). The pear stories: Cognitive, cultural and linguistic aspects of narrative production. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Y. R. (1973). A grammar of spoken Chinese. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (1964). The development of grammar in child language: Discussion. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 29(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, B. W.-Y., & McBride-Chang, C. (2003). Promoting language and literacy development through parent-child reading in Hong Kong preschoolers. Early Education and Development, 14(2), 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E. V. (2009). First language acquisition (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E. V. (2016). Language in children (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contemori, C., & Dussias, P. E. (2016). Referential choice in a second language: Evidence for a listener-oriented approach. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 31(10), 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K., & Engdahl, E. (1989). Null subjects in Zürich German. WPSS, 44, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, B. (1996). ‘Pragmatic weight’ and Spanish subject pronouns: The pragmatic and discourse uses of ‘tú’ and ‘yo’ in spoken Madrid Spanish. Journal of Pragmatics, 26(4), 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.-M. (2004). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence in French as a foreign language: An overview. Journal of French Language Studies, 14(3), 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. (2005). Dummy subject “ta” (他) in spoken Mandarin. Language Teaching and Linguistic Studies, 5, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, P. A., Liu, Y., & Li, D. (2017). Chinese heritage language learning: Negotiating identities, ideologies, and institutionalization. In O. E. Kagan, M. M. Carreira, & C. H. Chik (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of heritage language education: From innovation to program building (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, P. (2012). Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41(1), 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. G. H. (2011). Deletion of /t, d/ and the acquisition of linguistic variation by second language learners of English. Language Learning, 61(4), 1256–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, M. (1982). A study of social variation in adult second language acquisition. Language Learning, 32(2), 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELAN. (2024). Max Planck institute for psycholinguistics; The language archive (Version 6.8) [Computer software]. Available online: https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Erbaugh, M. S. (1982). Coming to order: Natural selection and the origin of syntax in the Mandarin speaking children [Doctoral dissertation, University of California]. [Google Scholar]

- Erker, D., & Guy, G. R. (2012). The role of lexical frequency in syntactic variability: Variable subject personal pronoun expression in Spanish. Language, 88(3), 526–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erker, D., Guy, G. R., Beaman, K. V., Bayley, R., Adli, A., Orozco, R., & Zhang, X. (in press). Subject pronoun expression: A cross-linguistic variationist sociolinguistic study. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ferrán, N. (2007). A bend in the road: Subject personal pronoun expression in Spanish after 30 years of sociolinguistic research: Subject personal pronoun expression in Spanish. Language and Linguistics Compass, 1(6), 624–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasti, M. T. (2002). Language acquisition: The growth of grammar. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haag-Merz, C. (1996). Pronomen im Schwabischen: Syntax und erwerb. Tectum. [Google Scholar]

- Hartsuiker, R. J., Pickering, M. J., & Veltkamp, E. (2004). Is syntax separate or shared between languages? Cross-linguistic syntactic priming in Spanish-English bilinguals. Psychological Science, 15(6), 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, J., & Brown, D. F. (1976). Developing sociolinguistic competence in a second language. TESOL Quarterly, 10(4), 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmquist, J. (2008). Gender in context: Features and factors in men’s and women’s speech in rural Puerto Rico. In M. Westmoreland, & J. A. Thomas (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 4th workshop on Spanish sociolinguistics (pp. 17–35). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y. (2020). Change in Chinese personal pronouns from a typological perspective. Linguistics Journal, 14(1), 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, J. H. (1987). A study of the various stages of development and acquisition of Mandarin Chinese by children milieu. (National Science Council Research Report). College of Foreign Languages, Fu Jen Catholic University. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, N. (1983). The pro-drop parameter in child grammars. Proceedings of the West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 2, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, N. (1986). Language acquisition and the theory of parameters. Reidel. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, N., & Wexler, K. (1993). On the grammatical basis of null subjects in child language. Linguistic Inquiry, 24(3), 421–459. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L., & Bayley, R. (2002). Null pronoun variation in Mandarin Chinese. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 8(3), 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L., & Ren, M. (Eds.). (2023). Personal pronouns and demonstrative pronouns. In A general theory of ancient Chinese (pp. 159–179). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. (2009, March 30). How the statistical revolution changes (computational) linguistics. EACL 2009 Workshop on the Interaction between Linguistics and Computational Linguistics (pp. 3–11), Athens, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, M. A., & Duarte, M. E. L. (2021). Parametric variation: The case of Brazilian Portuguese null subjects. In A. Bárány, T. Biberauer, J. Douglas, & S. Vikner (Eds.), Syntactic architecture and its consequences III: Inside syntax. Language Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Terry, K. M. (2022). At the intersection of SLA and sociolinguistics: The predictive power of social networks during study abroad. The Modern Language Journal, 106(1), 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J. (2000). Subject/object drop in the acquisition of Korean: A cross-linguistic comparison. Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 9(4), 325–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo-Brown, K. (2001). Heritage language instruction for post-secondary students from immigrant backgrounds. Heritage Language Journal, 1(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo-Brown, K., & Brown, J. D. (2017). Teaching Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Heritage Language students: Curriculum needs, materials, and assessment. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner City: Studies in the black English vernacular. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (1989). The child as linguistic historian. Language Variation and Change, 1(1), 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (2013). Preface: The acquisition of sociolinguistic variation. Linguistics, 51(2), 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. (1997). Finiteness and null arguments in child Cantonese [Paper presentation]. Workshop on the First Language Acquisition of East Asian Languages, LSA Summer Institute, Cornell University. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. (2014). Variation in subject pronominal expression in L2 Chinese. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 36(1), 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Bayley, R. (2018). Lexical frequency and syntactic variation: Subject pronoun use in Mandarin Chinese. Asia-Pacific Language Variation, 4(2), 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Chen, X., & Chen, W.-H. (2012). Variation of subject pronominal expression in Mandarin Chinese. Sociolinguistic Studies, 6(1), 91–199. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. (1995). 儿童语言的发展 Ertong Yuyan de Fanzhan [Children’s language development]. Huazhong Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, J. M., & Fernández Fuertes, R. (2019). Subject omission/production in child bilingual English and child bilingual Spanish: The view from linguistic theory. Probus, 31(2), 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L., & Liu, H. X. (1998). 修訂畢保德圖畫詞彙測驗 [Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised]. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lyster, R. (1994). The effect of functional-analytic teaching on aspects of French immersion students’ sociolinguistic competence. Applied Linguistics, 15(3), 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahowald, K., James, A., Futrell, R., & Gibson, E. (2016). A meta-analysis of syntactic priming in language production. Journal of Memory and Language, 91, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. (1969). Frog, where are you? Dial Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, R., Schembri, A., McKee, D., & Johnston, T. (2011). Variable “subject” presence in Australian Sign Language and New Zealand Sign Language. Language Variation and Change, 23(3), 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mede, E., & Dikilitaş, K. (2015). Teaching and learning sociolinguistic competence: Teachers’ critical perceptions. Participatory Educational Research, 2(3), 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W., & Ervin, S. (1964). The development of grammar in child language. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 29(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mougeon, R., Nadasdi, T., & Rehner, K. (2010). The sociolinguistic competence of immersion students. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, N. (2015). A sociolinguistic view of null subjects and VOT in Toronto heritage languages. Lingua, 164, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, N., Aghdasi, N., Denis, D., & Motut, A. (2011). Null subjects in heritage languages: Contact effects in a cross-linguistic context. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 17(2), 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, N., Blondeau, H., & Auger, J. (2003). Second language acquisition and “real” French: An investigation of subject doubling in the French of Montreal Anglophones. Language Variation and Change, 15(01). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M. (1996). Acquisition of Japanese empty categories. Kuroshio Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nanbakhsh, G. (2011). Persian address pronouns and politeness in interaction [Doctoral dissertation, University of Edinburgh]. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwland, M. S., Otten, M., & Van Berkum, J. J. A. (2007). Who are you talking about? Tracking discourse-level referential processing with event-related brain potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(2), 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco, R. (2015). Pronominal variation in Colombian Costeño Spanish. In A. Carvalho, R. Orozco, & N. L. Shin (Eds.), Subject pronoun expression in Spanish: A cross dialectal perspective (p. 22). Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, R., & Zentella, A. C. (2012). Spanish in New York: Language contact, dialectal leveling, and structural continuity. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes Silva, V. L. (1993). Subject omission and functional compensation: Evidence from written Brazilian Portuguese. Language Variation and Change, 5(1), 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2017). Priming and language change. In M. Hundt, S. Mollin, & S. E. Pfenninger (Eds.), The changing English language: Psycholinguistic perspectives (pp. 173–190). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polio, C. (1995). Acquiring nothing?: The use of zero pronouns by nonnative speakers of Chinese and the implications for the acquisition of nominal reference. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 17(3), 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, R. (2022). Acquiring sociolinguistic competence during study abroad: U.S. students in Buenos Aires. In R. Bayley, D. R. Preston, & X. Li (Eds.), Variation in second and heritage languages: Crosslinguistic perspectives (pp. 199–222). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, D. R., & Bayley, R. (1996). Second language acquisition and linguistic variation. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, R. (2010). Pronoun acquisition in a Mandarin—English bilingual child. International Journal of Bilingualism, 14(1), 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, V. (1996). Variation in French interlanguage: A longitudinal study of sociolinguistic competence. In R. Bayley, & D. R. Preston (Eds.), Second language acquisition and linguistic variation (pp. 177–202). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, V., Howard, M., & Lemée, I. (2009). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence in a study abroad context. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. (1997). Acquisition of variable rules: A study of (-t, d) deletion in preschool children. Journal of Child Language, 24(2), 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaine, S. (2003). Variation in language and gender. In J. Holmes, & M. Meyerhoff (Eds.), The handbook of language and gender (pp. 98–118). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkvist, H. (2018). Null subjects and distinct agreement in Modern Germanic. In F. Cognola, & J. Casalicchio (Eds.), Null subjects in generative grammar: A synchronic and diachronic perspective (Vol. 1, pp. 285–306). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankoff, G., Thibault, P., Nagy, N., Blondeau, H., Fonollosa, M.-O., & Gagnon, L. (1997). Variation in the use of discourse markers in a language contact situation. Language Variation and Change, 9(2), 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrank, F. A., & Wendling, B. J. (2018). The Woodcock-Johnson IV: Tests of cognitive abilities, tests of oral language, tests of achievement. In Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (4th ed, pp. 383–451). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Serratrice, L. (2007). Cross-linguistic influence in the interpretation of anaphoric and cataphoric pronouns in English–Italian bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 10(3), 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N. L. (2012). Variable use of Spanish subject pronouns by monolingual children in Mexico. In K. L. Geeslin, & M. Díaz-Campos (Eds.), The 14th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium (pp. 130–141). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, N. L., & Cairns, H. S. (2012). The Development of NP selection in school-age children: Reference and Spanish subject pronouns. Language Acquisition, 19(1), 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N. L., & Otheguy, R. (2009). Shifting sensitivity to continuity of reference: Subject pronoun use in Spanish in New York City. In Español en Estados Unidos y otros contextos de contacto: Sociolingüística, ideología y pedagogía. Iberoamericana Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J., & Durham, M. (2019). Sociolinguistic variation in children’s language: Acquiring community norms. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solan, L. (1983). Pronominal reference: Child language and the theory of grammar. Kluwer Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Sorace, A., Serratrice, L., Filiaci, F., & Baldo, M. (2009). Discourse conditions on subject pronoun realization: Testing the linguistic intuitions of older bilingual children. Lingua, 119(3), 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminga, M., MacKenzie, L., & Embick, D. (2016). The dynamics of variation in individuals. Linguistic Variation, 16(2), 300–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S. (1996). 古汉语主语省略的特殊现象 Gǔ hànyǔ zhǔyǔ shěnglüè de tèshū xiànxiàng [Null subject in Old Chinese]. 语文知识 Chinese Language, 11, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Cacoullos, R., & Travis, C. E. (2016). Two languages, one effect: Structural priming in spontaneous code-switching. Bilingualism, 19(4), 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, C. E. (2007). Genre effects on subject expression in Spanish: Priming in narrative and conversation. Language Variation and Change, 19(02). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valian, V. (1991). Syntactic subjects in the early speech of American and Italian children. Cognition, 40, 21–81. [Google Scholar]

- Valian, V., & Eisenberg, Z. (1996). The development of syntactic subjects in Portuguese-speaking children. Journal of Child Language, 23(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Compernolle, R. A., & Williams, L. (2012). Reconceptualizing sociolinguistic competence as mediated action: Identity, meaning-making, agency. The Modern Language Journal, 96(2), 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Lillo-Martin, D., Best, C. T., & Levitt, A. (1992). Null subject versus null object: Some evidence from the acquisition of Chinese and English. Language Acquisition, 2(3), 221–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger-Guntharp, H. (2006). Voices from the margin: Developing a profile of Chinese Heritage Language Learners in the FL classroom. Heritage Language Journal, 4(1), 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, A., Dudis, P., Bayley, R., & Lucas, C. (2002). Variable subject presence in ASL narratives. Sign Language Studies, 3(1), 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. (2006). Heritage learners in the Chinese language classroom: Home background. Heritage Language Journal, 4(1), 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. (2010). Chinese in the USA. In K. Potowski (Ed.), Language diversity in the USA (1st ed., pp. 81–95). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. Y., & Min, H. F. (1992). Chinese children’s acquisition of personal pronouns. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 4, 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R. F., & Lee, J. (2004). Identifying units in interaction: Reactive tokens in Korean and English conversations. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 8(3), 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M. (2005). Sociolinguistic competence in the complimenting act of native Chinese and American English speakers: A mirror of cultural value. Language and Speech, 48(1), 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D. (2017). Multidimensionality of morphological awareness and text comprehension among young Chinese readers in a multilingual context. Learning and Individual Differences, 56, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. (2021). Language variation in Mandarin as a Heritage Language: Subject personal pronouns. Heritage Language Journal, 18(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M., Chen, G., Ying, H., & Zhang, R. (1986). Children’s comprehension of personal pronouns. In M. Zhu (Ed.), 儿童语言发展研究 Ertong Yuyan Fazhan Yanjiu [Studies in child language development] (pp. 114–125). Huadong Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).