Case Marking in Turkish Heritage Children With and Without Developmental Language Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. DLD in Monolinguals

1.2. DLD in Agglutinative Languages

1.3. DLD and Heritage Language

1.4. Diagnostic Challenges in Assessing Bilingual Children

2. Case in Standard Turkish

2.1. Case Marking in Turkish

| (1) | a. | (Ben) | kalem-i | al-dı-m. |

| (I) | pencil_ACC | take-PAST-1SG | ||

| “(I) took the pencil.” | ||||

| b. | (Ben) | o-nu | al-dı-m. | |

| (I) | It-ACC | take-PAST-1SG | ||

| “(I) took it.” | ||||

| (2) | a. | Kız | oğlan-a | çiçek | ver-di |

| girl | boy-DAT | flower | give-PAST-3SG | ||

| “The girl gave a flower to the boy.” | |||||

| b. | Kız | okul-a | git-ti. | ||

| girl | school-DAT | go-PAST-3SG | |||

| “The girl went to school.” | |||||

| (3) | Ahmet | köy-de | yaş-ar. |

| Ahmet | village-LOC | Iive.PRES | |

| “Ahmet lives in the village.” | |||

| (4) | Adam | ev-i-nden | çık-ıyor-du. |

| the man | home-POSS.3SG-ABL | come out-PROG-PAST-3SG | |

| “The man was coming out of his home.” | |||

| (5) | Kadın-ın | boy-u | kısa. |

| women-GEN.3SG | height-POSS.3SG | short | |

| “The woman is short.” | |||

| (6) | Çocuk | oyuncak-la | oynuyor. |

| Child | toy-INST | play-PROG-3SG | |

| “The child is playing with the toy.” | |||

| (7) | Simple personal pronouns: seninle “with you” |

| Demonstrative pronouns: bununla “with this” | |

| kim “who”: kiminle “with whom” |

2.2. The Acquisition of Case Marking in Turkish

2.3. Case Marking in Heritage Turkish

| (8) | Target | ||||||||

| (Oda-m-ın | duvar-lar-ı-nda) | diploma | ve | resimli | yapboz-lar | var. | |||

| (Room-POSS.3SG-GEN | wall-PL-POSS:3G-LOC) | certificate | and | illustrated | puzzle-PL | exist | |||

| “(On the wall of my room) there’s a certificate and illustrated puzzles.” | |||||||||

| Response | |||||||||

| Urkunde | var, | ondan sonra | Puzzle-ler-den | resimler | |||||

| Certificate | exist | then | puzzle-PL-ABL | picture-PL | |||||

| *“There is a certificate, and then pictures (made) from puzzles.” (Boeschoten, 1994, p. 261) | |||||||||

| (9) | Target | ||||

| kadın | da | bir | kapı-yı | göster-di | |

| woman | and | DEF | door-ACC | show-PAST | |

| “And the woman pointed out a door.” | |||||

| Response | |||||

| kadın | da | bir | kapı-ya | göster-di (FEH, 1. Class) | |

| woman | and | DEF | door-DAT | show-PAST | |

| “And the woman pointed out a door.” | |||||

| (10) | Target | |

| İşyeri-ne | telefon ed-iyor-um. | |

| workplace- DAT | phone-PRES.PROG-1SG | |

| “I call to work.” | ||

| Response | ||

| telefon aç-ıyo-m | işyeri-ni | |

| phone-PRES.PROG-1SG | workplace- ACC | |

| “I call to work.” (Sirim, 2009, p. 55). | ||

| (11) | Target | ||||

| Park-ta-ki | kadın-lar-ın | dedikodu-lar-ı | ne | üzerine? | |

| park-LOC | woman-PL-GEN | gossip-PL-POSS-3SG | what | about-DAT | |

| “About what are the woman in park gossiping?” | |||||

| Response | |||||

| Park-ta-ki | kadın-lar | dedikodu-lar-ı | ne | üzerine? | |

| park-LOC | woman-PL-Ø | gossip-PL-POSS.3SG | what | about-DAT | |

| *“The woman in the park what about is their gossip?” (Cindark & Aslan, 2004, p. 4) | |||||

| (12) | Target | |||||||

| O kişi-nin | değişik | bir | ülke-den | gel-diği-nden | veya | |||

| this-person-GEN | different | DEF | country-DAT | come-FNOM-POSS-ABL | or | |||

| kültür-ü-nden | dolayı | dışla-n-ma-sı | ||||||

| culture-POSS.3SG-ABL | due to | exclude-PASS-FNOM-POSS- | ||||||

| çok | gör-ül-üyor. | |||||||

| often | see-PASS-PROG-3G | |||||||

| *“It is very common for that person to be excluded due to being from a different country or having (a different) culture.” | ||||||||

| Response | ||||||||

| O kişi-nin | değişik | bir | ülkeden, | veya | kültürü | dolayı | dışla-n-ma | |

| this-person-GEN | different | DEF | country-DAT | or | culture-ACC | due to | exclude-PASS-FNOM-Ø | |

| çok | görülüyor | |||||||

| often | see-PASS-PROG-3G | |||||||

| “It is very common for that person to be excluded due to from a different country or culture.”(Schroeder, 2014, p. 37) | ||||||||

| (13) | Target | |||||

| Kopya | çekmek-le | başka | insan-ın | hakkını | yersin. | |

| copy | take-INSR | another | person-GEN.3SG | right-POSS3SG-ACC | take-AO-2SG | |

| “By copying (in the exam) you cheat others of their rights.” | ||||||

| Response | ||||||

| Kopya | çekmek | başka | insan-ın | hakkı-sı-nı | yiyorsun | |

| copy | take | another | person-GEN.3SG | right-POSS.3SG-POSS.3SG-ACC | take-IPFV-2SG | |

| sayılır. | ||||||

| count-PASS-AOR | ||||||

| *“To copy it is considered you are cheating others of their rights.” (Küppers et al., 2015, p. 36). | ||||||

| (14) | Target | |

| Çanta-sı-yla | oynu-yor-du. | |

| bag-POSS3SG-INST | play-PROG-PAST-3SG | |

| “S/he played with his bag.” | ||

| Response | ||

| Çantasın-lan | oynu-yor-du. | |

| bag-POSS3SG-INST | play-PROG-PAST-3SG | |

| “S/he played with his bag.” (Şimşek & Schroeder, 2011, p. 213) | ||

2.4. Case Marking in DLD in Turkish

| (15) | Target | ||||

| Şimdi | ben | bu-nu | tak-a-yım | mı? | |

| Now | I | this-acc | attach-OPT-1SG | INT | |

| “Shall I attach it now?” | |||||

| Response | |||||

| Dimmi | ben | bu-Ø | gada (DLD-Fer, 6;5) | ||

| now | I | that- Ø (for ACC) | attach | ||

| *“I attach this now.” (Rothweiler et al., 2010, p. 550) | |||||

| (16) | Target | |||

| O | kedi | o-na | bak-ıyor. | |

| This | cat | he-DAT | look-PRES.PROG | |

| “This cat looks at him.” | ||||

| Response | ||||

| O | Katze | bakıyo | o-nu. (DLD-Dev, 5;5) | |

| This | cat | look-PRES.PROG | he-ACC | |

| “This cat looks at him.” (Rothweiler et al., 2010, p. 550) | ||||

| (17) | Target | |

| Atta-ya | gid-iyor. | |

| Out-DAT | go-PRES.PROG | |

| “S/he is going out.” | ||

| Response | ||

| Atta-yı | gid-iyo. | |

| Out-ACC | go-PRES.PROG | |

| “S/he is going out.” (Topbaş et al., 2016) | ||

| (18) | Target | ||

| Ayı | kepçe-yi | it-ti. | |

| bear | truck-ACC | hit-PAST | |

| “The bear hit the truck.” | |||

| Response | |||

| Ayı | it-ti | çepçe-Ø | |

| bear | hit-PAST | truck | |

| *”The bear hit the truck.” (Topbaş et al., 2016) | |||

2.5. Current Study

- How do heritage BiDLD children compare to their heritage BiTD peers and lL2 BiTDs in their production of case and possessive markers of standard Turkish?

- Which age and input variables predict variance in performance using case and possessive markers in standard and heritage Turkish?

- Given the potential overlap between features of heritage Turkish and clinical markers of DLD in standard Turkish, can case and possessive markers be used to identify DLD in the bilingual heritage context? Does performance on case and possessive markers improve if certain features of heritage Turkish are considered?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Materials

3.2.1. The Parental Questionnaire PaBiQ

3.2.2. Elicited Production of Turkish Case and Possessive Markers

3.3. Scoring

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

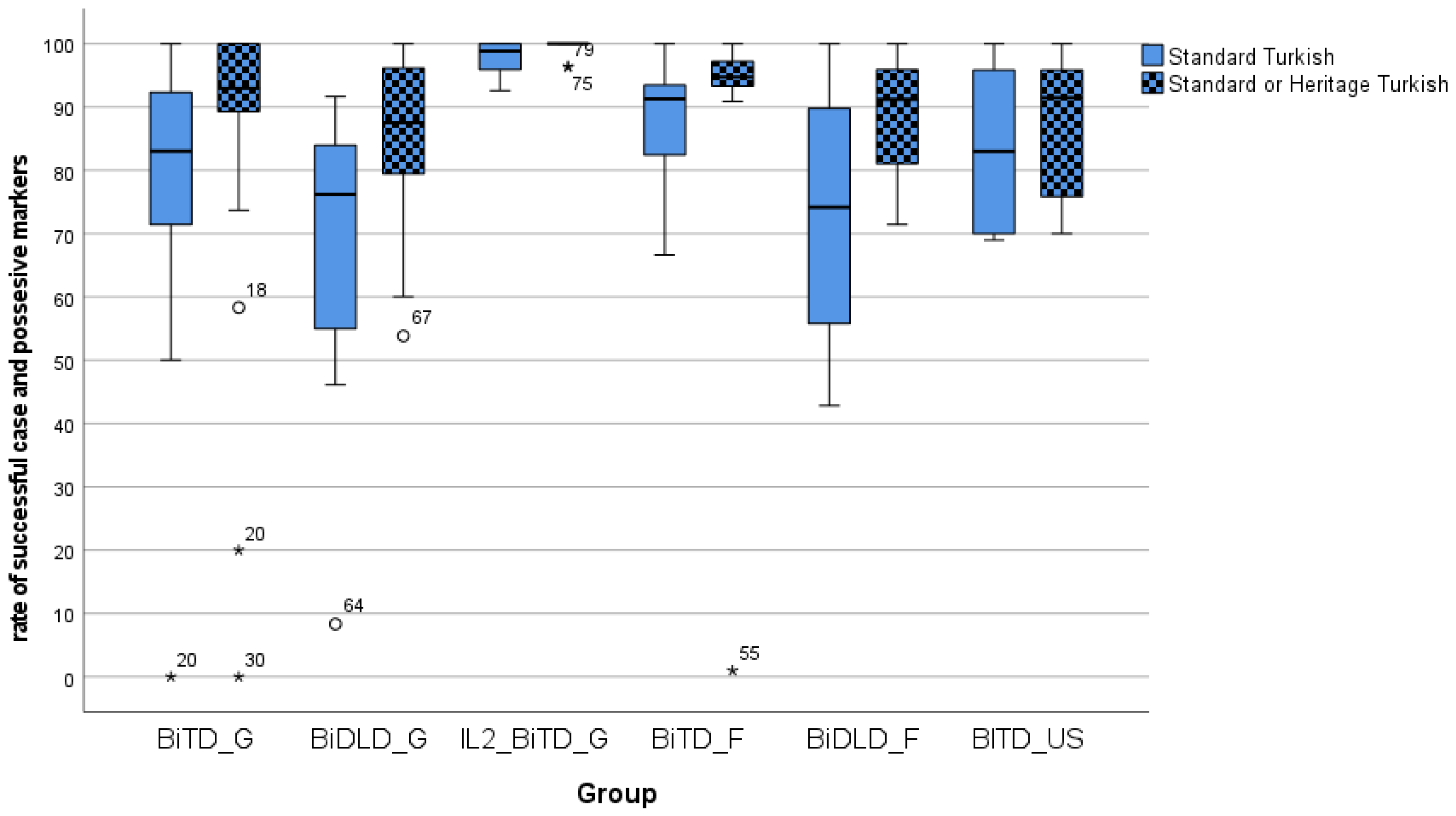

4.1. TEDIL: Case and Possessive Marker Comparisons

4.2. Factors Predicting Performance on Case and Possessive Markers

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| ABL | ablative case |

| ACC | accusative case |

| ADJ | adjective/adjectival/adjectivize |

| AOR | aorist |

| ADV | adverb/adverbializer |

| COP | copula |

| CV | converb |

| DAT | dative case |

| EV/PF | evidential/perfective |

| FNOM | factive nominalization |

| GEN | genitive case |

| IMPF | imperfective |

| INF | infinitive |

| INT | interrogative |

| LOC | locative case |

| NEG | negative |

| OBJP | object participle |

| OPT | optative |

| PAST | past tense |

| PART | participle |

| P.COP | past copula |

| PL | plural |

| POSS | possessive |

| PRES | present |

| PRES.PROG | present progressive |

| PROG | progressive |

| PSB | possibility |

| SG | singular |

| s/he | she, he (also “it”, depending on the context) |

| SUB | subordinator |

| SUBJP | subject participle |

| VN | verbal noun marker |

| 1 | first person |

| 2 | second person |

| 3 | third person |

| Ø | zero |

Appendix A

| Language | Test | Language Skills Tested | Scoring Method | Age Range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phonology | Vocabulary Expression | Vocabulary Reception | Morphosyntax Comprehension | Morphosyntax Production | ||||

| German | WWT 6–10a | Picture naming | Picture selection | - | Individual subtest scores | 5;6–10;11 | ||

| Lise-DaZ b | - | - | - | Picture–sentence matching, TVJT | Story, sentence completion, lead-in questions | Individual subtest scores | Monolinguals: 3;0–6;11 Bilinguals: 3;0–7;11 | |

| PLAKSS-II c | Picture naming | -- | - | - | Individual subtest scores | 2;6–7;11 | ||

| French | NEE-L d | - | Picture naming | Picture selection | Picture–sentence matching | Sentence completion | Individual subtest scores | 5;7–8;6 |

| BILO e | Word repetition | - | - | - | - | Individual subtest scores | 5;0–15;0 | |

| Turkish | TEDİL f | -- | Picture naming | Picture selection | Picture selection | Sentence completion/ construction | 2 composite scores, 1 production and 1 comprehension | 2;0–7;11 |

| 1 | DFG-ANR research project: Bilingual Language Development: Typically Developing Children and Children with Language Impairment (BiLaD). The BiLaD project was financed by a joint grant (German DFG: HA 2335/6-1, CH 1112/2-1, and RO 923/3-1) and a French ANR grant (ANR-12-FRAL-0014-01) awarded to Laurice Tuller, and Cornelia Hamann, Monika Rothweiler, and Solveig Chilla. It was carried out at the University of Tours, the University of Oldenburg, the University of Bremen, and the University of Education Heidelberg. |

| 2 | DFG research project: Bilingual Language Development in School-age Children with/without Language Impairment with Arabic and Turkish as first languages (BiliSAT). The BiliSAT project was funded by DFG Grants to CH 1112/4-1S (to Chilla) and HA 2335/7-1C (to Hamann). It was carried out at the University of Oldenburg and the University of Flensburg. |

References

- Aalberse, S., Backus, A., & Muysken, P. (2019). Heritage languages: A language contact approach. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Abed Ibrahim, L. (2025). Assessment of heritage language abilities in bilingual Arabic–German children with and without developmental language disorder: Comparing a standardized test battery for spoken arabic to an Arabic LITMUS sentence repetition task. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 68, 1569–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed Ibrahim, L., & Hamann, C. (2016, November 4–6). Bilingual Arabic-German & Turkish-German children with and without specific language impairment: Comparing performance in sentence and nonword repetition tasks [Paper presentation]. The 41st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development (pp. 1–17), Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Acarlar, F., & Johnston, J. R. (2011). Acquisition of Turkish grammatical morphology by children fifth developmental disorders. Journal for Communication Disorders, 46(5), 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarlar, F., Miller, J., & Johnston, J. (2006). Systematic analysis of language transcripts (SALT) Turkish (Version 9) [Computer software]. Turkish Psychological Association.

- Akıncı, M.-A. (2002). Développement des compétences narratives des enfants bilingues Turc-Français en France âgés de 5 à 10 ans [Development of narrative competence of bilingual Turkish-French children in France between the ages of 5 and 10] (Vol. 3). LINCOM studies in language acquisition. LINCOM. [Google Scholar]

- Akıncı, M.-A. (2008). Language use and biliteracy practices of Turkish-speaking children and adolescents in France. In V. Lytra, & J. N. Joergensen (Eds.), Multilingualism and identities across contexts: Cross-disciplinary perspectives on Turkish-speaking youth in Europe (pp. 85–108). University of Copenhagen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Akıncı, M.-A. (2018). Relative clauses in the written texts of French and Turkish bilingual and monolingual children and teenagers. In M. A. Akıncı, & K. Yağmur (Eds.), The rouen meeting: Studies on Turkic structures and language contacts (Vol. 114, pp. 217–230). Turcologica. Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Akıncı, M.-A. (2021). Cognate and non-cognate lexical access in Turkish of bilingual and monolingual 5-year-old nursery school children. Dilbilim Araştırmaları Dergisi, 32(3), 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıncı, M.-A., & Decool-Mercier, N. (2010). Aspects of language acquisition and disorders in Turkish-French bilingual children. In I. S. Topbaş, & M. Yavaş (Eds.), Communication disorders in Turkish in monolingual and multilingual settings (pp. 312–351). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Akıncı, M.-A., & Koçbaş, D. (2002, August 7–9). Literacy development in bilingual context: The case Turkish of bilingual and monolingual children and teenagers [Paper presentation]. 11th international conference on Turkish linguistics (pp. 547–562), Famagusta, Cyprus. [Google Scholar]

- Akıncı, M.-A., & Yagmur, K. (2000, August 16–18). Language use and attitudes of Turkish immigrants in France and their subjective ethnolinguistic vitality perceptions [Paper presentation]. 10th international conference on Turkish linguistics (pp. 299–309), İstanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Aksu-Koç, A. (2010). Normal language development in Turkish. In S. Topbaş, & M. Yavaş (Eds.), Communication disorders in Turkish in monolingual and multilingual settings (pp. 65–104). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Altinkamis, F., & Simon, E. (2020). Language abilities in bilingual children: The effect of family background and language exposure on the development of Turkish and Dutch. International Journal of Bilingualism, 24(5–6), 931–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA. (2004). Preferred practice patterns for the profession of speech-language pathology [preferred practice patterns. Available online: https://www.asha.org/policy/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Armon-Lotem, S., de Jong, J., & Meir, N. (Eds.). (2015). Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Babur, E., Rothweiler, M., & Kroffke, S. (2007). Spezifische sprachentwicklungsstörung in der erstsprache Türkisch. Lin guistische Berichte, 212, 377–402. [Google Scholar]

- Backus, A. (2003). Can a mixed language be conventionalized—Alternational codeswitching? In Y. Matras, & P. Bakker (Eds.), The mixed language debate. Theoretical and empirical advances (pp. 237–340). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Backus, A. (2013). Turkish as an immigrant language in Europe. In T. K. Bhatia, & W. C. Ritchie (Eds.), The handbook of bilingual ism and multilingualism (pp. 770–790). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Backus, A., & Boeschoten, H. (1998). Language change in immigrant Turkish. In G. Extra, & J. Marteens (Eds.), Multilingualism in a multicultural context. Case studies on South Africa and western Europe (pp. 221–238). Tilburg University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Backus, A., Demirçay, D., & Sevinç, Y. (2013). Converging evidence on contact effects on the second and third generation immigrant Turkish. Babylon. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, F. (Ed.). (2020). Studies in Turkish as a heritage language. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, F., Rothman, J., Iverson, M., Miller, D., Mayenco, E. P., Kupisch, T., & Westergaard, M. (2017). Differences in use without deficiencies in competence: Passives in the Turkish and German of Turkish heritage speakers in Germany. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(8), 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, L. M., & Leonard, L. (1998). Specific language impairment and grammatical morphology: A discriminant function analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41(5), 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, L. M., & Leonard, L. (2001). Grammatical morphology deficits in Spanish-speaking children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 44(4), 905–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, L. M., & Leonard, L. (2005). Verb inflections and noun phrase morphology in the spontaneous speech of Spanish-speaking children with specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 26(2), 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, S., & Grim, J. (2012). Assessment of young children with special needs: A context-based approach (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernreuter, M. (2004). Türkçe-Almanca ikidilli çocuklarda özgün dil bozukluklari: Anadilin çekim morfolojisinde klinik belirtilerin aranmasinda ilk adimlar. 2. Ulusal dil ve konuşma bozukluklari kongresi. Bildiri kitabi içinde (S. Topbaş, Ed.; pp. 106–113). Kök Yayıncılık, Dilkom. [Google Scholar]

- Bezcioglu-Göktolga, I., & Yagmur, K. (2018). Home language policy of second-generation Turkish families in the Netherlands. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(1), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. V. (1994). Grammatical errors in specific language impairment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 33, 3–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, D. V., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T., & CATALISE Consortium. (2016). CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary delphi consensus study. Identifying language impairments in children. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0158753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. V., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T., & CATALISE-2 Consortium. (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 58(10), 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, E., & Boerma, T. (2017). Effects of language impairment and bilingualism across domains. Vocabulary, morphology and verbal memory. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 7(3), 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, E., Boerma, T., & De Jong, J. (2019). First language attrition and developmental language disorder. In M. S. Schmid, & B. Köpke (Eds.), The oxford handbook of language attrition (pp. 108–120). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, E., Boerma, T., Karaca, F., de Jong, J., & Küntay, A. (2022). Grammatical development in both languages of bilingual Turkish-Dutch children with and without developmental language disorder. Frontiers in Communication, 7, 1059427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeschoten, H. (1994). L2 influence on L1 development: The case of Turkish children in Germany. In G. Extra, & L. Verhoeven (Eds.), The cross-linguistic study of bilingual development (pp. 253–264). North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Boeschoten, H. (2000). Convergence and divergence in migrant Turkish. In K. J. Mattheier (Ed.), Dialect and migration in a changing Europe (pp. 145–154). Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnacker, U., & Karakoç, B. (2020). Subordination in children acquiring Turkish as a heritage language in Sweden. In F. Bayram (Ed.), Studies in Turkish as a heritage language (pp. 155–206). John Benjamin. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnacker, U., Lindgren, J., & Öztekin, B. (2016). Turkish-and German-speaking bilingual 4-to-6-year-olds living in Sweden: Effects of age, SES and home language input on vocabulary production. Journal of Home Language Research, 1, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, U., Arfé, B., Caselli, M. C., Degasperi, L., Deevy, P., & Leonard, L. B. (2006). Clinical markers for specific language impairment in Italian: The contribution of clitics and nonword repetition. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 41, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, U., Caselli, M. C., & Leonard, L. B. (1997). Grammatical deficits in Italian-speaking children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40(4), 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castilla-Earls, A., Auza, A., Péréz-Leroux, A. T., Fulcher-Rood, K., & Barr, C. (2020). Morphological errors in monolingual Spanish-speaking children with and without developmental language disorders. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 51, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Shirai, Y. (2010). The development of aspectual marking in child Mandarin. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrie-Muller, C., & Plaza, M. (2001). N-EEL Nouvelles épreuves pour l’examen du langage. ECPA. [Google Scholar]

- Chiat, S. (2015). Nonword repetition. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Methods for assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (pp. 125–151). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Chilla, S. (2022). Assessment of developmental language disorders in bilinguals: Immigrant Turkish and the standard-with dialect challenge in Germany. In E. Saiegh-Haddad, L. Laks, & C. McBride (Eds.), Handbook of literacy in diglossia and dialectal contexts—Psycholinguistic and educational perspectives. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chilla, S., & Babur, E. (2010). Specific language impairment in Turkish-German successive bilingual children. aspects of assessment and outcome. In S. Topbaş, & M. Yavaş (Eds.), Communication disorders in Turkish in monolingual and multilingual settings (pp. 65–104). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Chilla, S., & Şan, N. H. (2017). Möglichkeiten und grenzen der diagnostik erstsprachlicher fähigkeiten: Türkisch-deutsche und türkisch-französische kinder im vergleich. In C. Yildiz, N. Topaj, R. Thomas, & I. Gülzow (Eds.), Sprachen 2016: Russisch und Türkisch im fokus (pp. 175–205). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Chondrogianni, V., & Marinis, T. (2012). Production and processing asymmetries in the acquisition of tense morphology by sequential bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition, 15, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cindark, İ., & Aslan, S. (2004). Deutschlandtürkisch? Mannheim: Open-access publikationsserver des IDS. Available online: http://www.ids-mannheim.de/fileadmin/prag/soziostilistik/Deutschlandtuerkisch.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Clahsen, H. (1991). Child language and development dysphasia. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen, H., Bartke, S., & Göllner, S. (1997). Formal features in impaired grammars: A comparison of English and German SLI children. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 10, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun Kunduz, A. (2022). Heritage language acquisition and maintenance of Turkish in the United States: Challenges to teaching Turkish as a heritage language. Dilbilim Dergisi—Journal of Linguistics, 38, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun Kunduz, A., & Montrul, S. A. (2022a). Relative clauses in child heritage speakers of Turkish in the United States. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 14(2), 218–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun Kunduz, A., & Montrul, S. A. (2022b). Sources of variability in the acquisition of differential object marking by Turkish heritage language children in the United States. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 25, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronel-Ohayon, S. (2004). Etude longitudinale d’une population d’enfants dysphasiques [Doctoral dissertation, University of Geneva]. [Google Scholar]

- Csató, E., & Johanson, L. (1998). Turkish. In L. Johanson, & E. Csató (Eds.), The Turkic languages (pp. 203–235). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Çavuș, N. (2009). In search of clinical markers in Turkish SLI; An analysis of the nominal morphology in Turkish bilingual children [Master’s thesis, Universities of Amsterdam]. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, C. (2005). The grammars of Hungarian outside Hungary from a linguistics-typological perspective. In A. A. Fenyvesi (Ed.), Hungarian language contact outside Hungary (pp. 351–370). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J., Cavuş, N., & Baker, A. (2010). Language impairment in Turkish-Dutch bilingual children. In S. Topbaş, & M. Yavaş (Eds.), Communication disorders in Turkish in monolingual and multilingual settings (pp. 288–300). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Doğruöz, A. S., & Backus, A. (2009). Innovative constructions in Dutch Turkish: An assessment of on-going contact-induced change. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition, 12(1), 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, W. U. (1997). Studies on pre-and proto-morphology. Austrian Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Dromi, E., Leonard, L., & Shtiman, M. (1993). The grammatical morphology of Hebrew speaking children with specific language impairment: Some competing hypotheses. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, K., Mok, P. L. H., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2015). Core subjects at the end of primary school: Identifying and explain ing relative strengths of children with specific language impairment (SLI). International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50, 226–240. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbeiss, S., Bartke, S., & Clahsen, H. (2005). Structural and lexical case in child German: Evidence from language-impaired and typically developing children. Language Acquisition, 13, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekçi, Ö. (1987). Creativity in the language acquisition. In H. E. Boeschoten, & L. T. Verhoeven (Eds.), Studies on modern Turkish Tilburg (pp. 203–210). Tilburg University. [Google Scholar]

- Erguvanlı, E. (1984). The functions of word order in Turkish grammar. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Felser, C., & Arslan, S. (2019). Inappropriate choice of definite articles in Turkish heritage speakers of German. Heritage Language Journal, 16, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, C. (2015). Understanding heritage language acquisition. Some contributions from the research on heritage speakers of European Portuguese. Lingua, 164, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, C. (2020). Attrition and reactivation of a childhood language: The case of returnee heritage speakers. Language Learning, 70(S1), 85–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Boyer, A. (2014). Psycholinguistischer analyse kindlicher Aussprachestörungen-II: PLAKSS II. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Fredman, M. (2006). Recommendations for working with bilingual children—Prepared by the multilingual affairs committee of IALP. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 58, 458–464. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, S., & Fukuda, S. (1999). Developmental language impairment in Japanese; A linguistic investigation. McGill Working Papers in Linguistics, 10, 150–177. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, S., Fukuda, S., It, T., & Yamaguchi, Y. (2007). Grammatical impairment of case assignment in Japanese children with specific language impairment. The Japan Journal of Logopedics and Phoniatrics, 48, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glück, C. W. (2011). WWT 6–11. Wortschatz-und wortfindungstest für 6–10 jährige kinder. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gökgöz, K., Gagarina, N., & Klassert, A. (2020). Kasuserwerb in der erstsprache Türkisch: Eine untersuchung zur akkusativ-und dativproduktion von bilingual türkisch-deutschsprachigen kindern. Stimm, Sprache, Gehör, 44(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksel, A., & Kerslake, C. (2005). Turkish: A comprehensive grammar. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Güven, S., & Leonard, L. (2020). The production of noun suffixes by Turkish-speaking children with developmental language disorder and their typically developing peers. Journal for Communication Disorders, 55(3), 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, C., & Abed Ibrahim, L. (2017). Methods for identifying specific language impairment in bilingual populations in Germany. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, C., Chilla, S., Ibrahim, L. A., & Fekete, I. (2020). Language assessment tools for Arabic-speaking heritage and refugee children in Germany. Applied Psycholinguistics, 41(6), 1375–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, C., Zesiger, P., Dubé, S., Frauenfelder, U., Starke, M., & Rizzi, L. (2003). Aspects of the grammatical development in young French children with SLI. Developmental Science, 6(2), 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamurcu-Süverdem, B., & Akıncı, M. A. (2017). Study on language development of Turkish preschool children. Revue Française de Linguistique Appliquée, xxi(2), 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, K., Nettelbladt, U., & Leonard, L. (2000). Specific language impairment in Swedish: The status of verb morphology and word order. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 43, 848–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herkenrath, A., & Rehbein, J. (2012). Pragmatic corpus analysis. In T. Schmidt, & K. Wörner (Eds.), Multilingual corpora and multilingual corpus analysis (pp. 123–152). Hamburg Studies in Multilingualism 14. Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hertel, I., Chilla, S., & Abed Ibrahim, L. (2022). Special needs assessment in bilingual school-age children in Germany. Languages, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hresko, W., Reid, K. D., & Hammill, D. D. (1999). Examiner’s manual: Test of early language development (3rd ed.). Pro-ed. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released. (2020). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 27.0). IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Iefremenko, K., & Schroeder, C. (2019). Göçmen Türkçesinde cümle birleştirme. Pilot çalışma [Clause-combining in heritage Turkish: A pilot study]. In K. İşeri (Ed.), Dilbilimde güncel tartişmalar [Current Debates in Linguistics] (pp. 247–255). Dilbilim Derneği Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics [IALP]. (2006). Recommendations for working with bilingual children. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 58, 456–464. Available online: https://karger.com/fpl/article-pdf/58/6/456/2801962/000096570.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Jakubowicz, C. (2003). Computational complexity and the acquisition of functional categories by French-speaking children with SLI. Linguistics, 41, 175–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowicz, C., & Tuller, L. (2008). Specific language impairment in French. In D. Ayoun (Ed.), Studies in French applied linguistics (pp. 97–134). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, L. (1991). Zur sprachentwicklung der ‘Turcia Germanica’. In I. Baldauf, K. Kreiser, & S. Tezcan (Eds.), Türkische sprachen und literaturen (pp. 199–212). Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, L. (2002). Structural factors in Turkic language contacts. Curzon. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. J., Beitchman, J., & Brownlie, E. B. (2010). Twenty-year follow-up of children with and without speech–language impairments: Family, educational, occupational, and quality of life outcomes. American Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 19(1), 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, I. (2007). Die türkischen „Power Girls“: Lebenswelt und kommunikative stile einer migrantengruppe in Mannheim, Tübingen. Studien zur Deutschen Sprache 39. Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Ketrez, F. N., & Aksu-Koç, A. (2009). Early nominal morphology: Emergence of case and number. In U. Stephany, M. Voeika, & M. M. Voeika (Eds.), The development of number and case in the first language acquisition: A crosslinguistic perspective (pp. 15–48). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketrez, N. (2004). Children’s accusative case and indefinite objects. Dilbilim Arastırmaları, 2004, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Khomsi, A., Khomsi, J., Pasquet, F., & Parbeau-Guéno, A. (2007). Bilan informatisé de langage oral au cycle 3 et au collège (BILO-3C). Éditions du Centre de psychologie appliquée. [Google Scholar]

- Köpke, B. (2007). Language attrition at the crossroad of brain, mind, society. In B. Köpke, M. S. Schmid, M. Keijzer, & S. Dostert (Eds.), Language and attrition. Theoretical perspectives (pp. 9–37). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, E., & Roberts, L. (2020). Over-sensitivity to the animacy constraint on DOM in low proficient Turkish heritage speakers. In A. Mandrale, & S. Montrul (Eds.), The acquisition of differential object marking (pp. 313–342). Trends in language acquisition research, 261. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Küppers, A., Şimşek, Y., & Schroeder, C. (2015). Turkish as a minority language in Germany: Aspects of language development and language instruction. Zeitschrift Für Fremdsprachenforschung, 26(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R. (2009). Język w zagrożeniu: Przyswajanie języka polskiego w warunkach polsko-szwedzkiego bilingwizmu. Universitas. [Google Scholar]

- Law, J., Reilly, S., & Snow, P. C. (2013). Child speech, language and communication need re-examined in a public health context: A new direction for the speech and language therapy profession. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(5), 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisiö, L. (2006). Genitive subjects and objects in the speech of the Finland Russians. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 14, 289–316. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, L. B. (2014). Children with specific language impairment. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, L. B., Caselli, M. C., & Devescovi, A. (2002). Italian children’s use of verb and noun morphology during the preschool years. First Language, 22, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. B., & Dromi, E. (1994). The use of Hebrew verb morphology by children with specific language impairment and by children developing language normally. First Language, 14, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. B., Kunnari, S., Savinainen-Makkonen, T., Tolonen, A. K., Mäkinen, L., Luotenen, M., & Leinonen, E. (2014). Noun case suffix use by children with specific language impairment: An examination of Finnish. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35, 833–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. B., Salameh, E.-K., & Hansson, K. (2001). Noun phrase morphology in Swedish-speaking children with specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 22, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, D. F., & Leonard, L. B. (1991). Subject case marking and verb morphology in normally developing and specifically language-impaired children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34(2), 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohndal, T., Rothman, J., Kupish, T., & Westergaard, M. (2019). Heritage language acquisition: What it reveals and why it is important for formal linguistic theories. Language and Linguistic Compass, 36, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukács, Á., Kas, B., & Leonard, L. B. (2013). Case marking in Hungarian children with specific language impairment. First Language, 33(4), 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukács, Á., Laurence, L., Bence, K., & Csaba, P. (2009). The use of tense and agreement by Hungarian-speaking children with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukács, Á., Leonard, L., & Kas, B. (2010). The use of noun morphology by children with language impairment: The case of Hungarian. International Journal of Language Communication and Disorders, 45, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łyskawa, P., & Nagy, N. (2020). Case marking variation in heritage slavic languages in Toronto: Not so different. Language Learning, 70(S1), 122–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, U. (2008). Sprache und sprachen in der migrationsgesellschaft: Die schriftkulturelle dimension. V & R unipres. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, U. (2010). Literaat und orat. Grundbegriffe der analyse geschriebener und gesprochener sprache. Grazer Linguistischen Studien, 73, 21–150. [Google Scholar]

- Makrodimitris, C., & Schulz, P. (2021). Does timing in acquisition modulate heritage children’s language abilities? Evidence from the Greek LITMUS sentence repetition task. Languages, 6(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinis, T., & Armon-Lotem, S. (2015). Sentence repetition. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (pp. 95–122). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Marinis, T., Armon-Lotem, S., & Pontikas, G. (2017). Language impairment in bilingual children state of the art. In J. Rothman, & S. Unsworth (Eds.), Linguistic approaches to bilingualism (7th ed., pp. 265–276). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Mastropavlou, M., & Marinis, T. (2002, June 1). Definite articles and case marking in the speech of Greek normally developing children and children with SLI. Euro Conference on the Syntax of Normal and Impaired Language, Corinth, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel, J. M. (2007). The weaker language in early child bilingualism: Acquiring a first language as a second language? Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(3), 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisel, J. M. (2009). Second language acquisition in early childhood. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft, 28, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2008). Incomplete acquisition in bilingualism. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, S. (2016). The acquisition of heritage languages. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, S., & Bowles, M. (2009). Back to basics: Differential object marking under incomplete acquisition in Spanish heritage speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 12, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M. (1995). Error analysis of pronouns by normal and language-impaired children. Journal of Communication Disorders, 28, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murao, A., Matsumoto-Shimamori, S., & Ito, T. (2012). Case-marker errors in the utterances of 2 children with specific language impairment: Focusing on structural and inherent cases. The Japan Journal of Logopedics and Phoniatrics, 53, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, N. (2016). Heritage languages as new dialects. In M.-H. Côté, & R. Knooihuizen (Eds.), Dialectology XV (pp. 15–34). Germany Language Science. [Google Scholar]

- Özsoy, O., Çiçek, B., Özal, Z., Gagarina, N., & Sekerina, I. A. (2023). Turkish-German heritage speakers’ predictive use of case: Webcam-based vs. in-lab eye-tracking. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1155585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, O., Iefremenko, K., & Schroeder, C. (2022). Shifting and expanding clause combining strategies in heritage Turkish varieties. Languages, 7(3), 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, D., Rothweiler, M., Tsimpli, I.-M., Chilla, S., Fox-Boyer, A., Katsika, K., Mastropavlou, M., Mylonaki, A., & Stahl, N. (2009). Motion verbs in Greek and German: Evidence from typically developing and SLI children. Selected Papers on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics ISTAL, 18, 298–299. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, J. (2010). The interface between bilingual development and specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J., Soto-Corominas, A., Daskalaki, E., Chen, X., & Gottardo, A. (2021). Morphosyntactic development in first generation Arabic-English children: The effect of cognitive, age, and input factors over time and across languages. Languages, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J., Tulpar, Y., & Arppe, A. (2016). Chinese L1 children’s English L2 verb morphology over time: Individual variation in long-term outcomes. Journal of Child Language, 43(3), 553–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, C. W. (1991). Turkish in contact with German: Language maintenance and loss among immigrant children in west Berlin. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 90, 97–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A. (2011). Linguistic competence, poverty of the stimulus and the scope of native language acquisition. In C. Flores (Ed.), Múltiplos olhares sobre o bilinguismo [Multiple views on bilingualism] (pp. 115–143). Humus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (1995). Cross-linguistic parallels in language loss. Southwest Journal of Linguistics, 14, 87–123. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, M. (2006). Incomplete acquisition: American Russian. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 14, 191–226. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, M. (2008). Gender under incomplete acquisition: Heritage speakers’ knowledge of noun categorization. Heritage Language Journal, 6(1), 40–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (2011). Reanylysis in Adult Heritage Language: New Evidence in Support of Attrition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 33(2), 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (2018). Heritage languages and their speakers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D. R. (1986). The case of American Polish. In D. Kastovsky, & A. Szwedek (Eds.), Linguistics across historical and geographyical boundaries: In honour of Jacek Fisiak on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday (pp. 1015–1023). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, M., & Sánchez, L. (2013). How incomplete is incomplete acquisition?—A prolegomenon for modeling heritage Rothweiler, grammar. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 3, 478–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A., & Ramos, E. (2001). Case, agreement and EPP: Evidence from an English-speaking child with SLI. Essex Research Reports in Linguistics, 36, 42–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rehbein, J., Herkenrath, A., & Karakoç, B. (2009). Turkish in Germany—On contact-induced language change of an immigrant language in the multilingual landscape of Europe. STUF—Language Typology and Universals, 62(3), 171–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M. L., & Wexler, K. (1996). Toward tense as a clinical marker of specific language impairment in English-speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 39, 1239–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, M. L., & Wexler, K. (2001). Test of early grammatical impairment. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. S., & Leonard, L. B. (1997). Grammatical deficits in German and English: A crosslinguistic study of children with specific language impairment. First Language, 17(50), 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, A., & Leonard, L. (1990). Interpreting deficits in grammatical morphology in specifically language-impaired children: Preliminary evidence from Hebrew. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 4(2), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, J. (2009). Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, J., & Kupisch, T. (2018). Terminology matters!: Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism, 22, 564–582. [Google Scholar]

- Rothweiler, M. (2006). The acquisition of V2 and subordinate clauses in early successive acquisition of German. In C. Lle’o (Ed.), Interfaces in multilingualism. Acquisition and representation. Hamburg studies on multilingualism (pp. 91–113). Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Rothweiler, M., Chilla, S., & Babur, E. (2010). Specific language impairment in Turkish. Evidence from Turkish-German successive bilinguals. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 24(7), 540–555. [Google Scholar]

- Rothweiler, M., Chilla, S., & Clahsen, H. (2012). Subject verb agreement in specific language impairment: A study of monolingual and bilingual German-speaking children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(1), 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists Specific Interest Group in Bilingualism [RCSLT]. (2007). Good practice for speech and language therapists working with clients from linguistic minority communities. RCSLT. [Google Scholar]

- Ruigendijk, E. (2015). Contrastive elicitation task for testing case marking. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (pp. 38–54). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, A. (1993). Turkish language development in the Netherlands. In G. Extra, & L. Verhoeven (Eds.), Immigrant languages in Europe (pp. 147–157). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Schellhardt, C., & Schroeder, C. (2013). Nominalphrasen in deutschen und türkischen texten mehrsprachiger schüler/innen. In K.-M. Köpcke, & A. Ziegler (Eds.), Deutsche grammatik im kontakt in schule und unterricht (pp. 241–262). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Schellhardt, C., & Schroeder, C. (Eds.). (2015). MULTILIT. Manual, criteria of transcription and analysis for German, Turkish and English. Universitätsverlag. Available online: https://scispace.com/pdf/multilit-manual-criteria-of-transcription-and-analysis-for-3z4ju50hz6.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Scherger, A.-L. (2019). Dative case marking in 2L1 and L2 bilingual SLI. In P. Guijarro Fuentes, & C. Suárez-Gómez (Eds.), Language acquisition and development—Proceedings of the GALA 2017 (pp. 95–115). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, M. S., & Karayayla, T. (2020). The roles of age, attitude, and use in first language development and attrition of Turkish–English bilinguals. Language Learning, 70(S1), 54–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S., & Yılmaz, G. (2018). Predictors of language dominance: An integrated analysis of first language attrition and second language acquisition in late bilinguals. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C. (2014). Türkische texte deutsch-türkisch bilingualer schülerinnen und schüler in Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik, 44, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C. (2016). Clause combining in Turkish as a minority language in Germany. In M. Güven, D. Akar, B. Öztürk, & K. Melte (Eds.), Exploring the Turkish linguistic landscape: Essays in honour of Eser E. Erguvanlı-Taylan (pp. 81–102). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, C. (2020). Acquisition of Turkish literacy in Germany. Research article. In Linguistic minorities in Europe. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C., & Dollnick, M. (2013). Mehrsprachige gymnasiasten mit türkischem hintergrund schreiben auf Türkisch. Available online: https://biecoll.ub.uni-bielefeld.de/index.php/mehrsprachig/article/view/319/412 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Schulz, P., & Tracy, R. (2011). Linguistische sprachstandserhebung—Deutsch als zweitsprache (LiSe-DaZ). Hogrefe Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M., Minkov, M., Dieser, E., Protassova, E., & Polinsky, M. (2015). Acquisition of Russian gender agreement by monolingual and bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism, 19(6), 726–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirim, E. (2009). Das Türkische einer deutsch-türkischen migrantinnengruppe. IDS. [Google Scholar]

- Stothard, S., Snowling, M., Bishop, D., Chipchase, B. B., & Kaplan, C. (1998). Language-impaired preschoolers: A follow-up into adolescence. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şan, N. H. (2008). Contact-induced language change in the Turkish noun phrase in bilingual Turkish student in Germany [Master’s thesis, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg]. [Google Scholar]

- Şan, N. H. (2018). First language assessment of Turkish–German and Turkish–French bilingual children with specific language impairment. In M. A. Akinci, & K. Yağmur (Eds.), The rouen meeting: Studies on Turkic structures and language contacts (Vol. 114, pp. 267–297). Turcologica. Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Șan, N. H. (2023). Subordination in Turkish heritage children with and without developmental language impairment. Languages, 8(4), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, Y., & Schroeder, C. (2011). Migration und Sprache in deutschland am beispiel der migranten aus der Türkei und ihrer kinder und kindeskinder. In Ş. Özil, M. Hofmann, & Y. Dayıoğlu-Yücel (Eds.), Fünfzig jahre türkische arbeitsmigration in Deutschland (pp. 205–228). V & R unipress. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, Ö. (2020). Sprachliche besonderheiten der Türken in Deutschland. In M. Önsoy, & M. Er (Eds.), Türkisch-Deutsche studien, band I: Beiträge aus den sozialwissenschaften (pp. 353–372). Nobel. [Google Scholar]

- Thordardottir, E. (2015). Proposed diagnostic procedures for use in bilingual and cross-linguistic context. In Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (pp. 331–358). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin, J. B. (2008). Validating diagnostic standards for specific language impairment using adolescent outcomes. In C. F. Norbury, J. B. Tomblin, & D. V. M. Bishop (Eds.), Understanding developmental language disorders: From theory to practice (pp. 93–114). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Topbaș, S. (1997). Phonological acquisition of Turkish children: Implications for phonological disorders. European Journal of Disorders of Communication, 32(4), 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topbaş, S. (2010). Specific language impairment in Turkish: Adapting the test of early language development (TELD-3) as a first step in measuring language impairment. In S. Topbaş, & M. Yavas (Eds.), Communication development and disorders (pp. 136–155). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Topbaş, S., Cangökçe-Yaşar, Ö., & Ball, M. (2012). LARSP: Turkish. In M. J. Ball, D. Cyristal, & P. Fletcher (Eds.), Assessing grammar: The language of LARSP (pp. 282–305). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Topbaş, S., & Güven, S. (2011). Türkçe erken dil gelişim testi-TEDİL-3. Detay. [Google Scholar]

- Topbaş, S., Güven, S., Uysal, A. A., & Kazanoğlu, D. (2016). Language impairment in Turkish-speaking children. In B. Haznedar, & F. N. Ketrez (Eds.), The acquisition of Turkish in childhood (pp. 295–324). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Topbaş, S., & Maviş, İ. (2016). Comparing measures of spontaneous speech of Turkish-speaking children with and without language impairment. In J. L. Patterson, & B. L. Rodriguaez (Eds.), Multilingual perspectives on child language disorders (pp. 209–227). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Topbaş, S., Maviş, İ., & Başal, M. (1997). Acquisition of bound morphemes nominal case morphology in Turkish. In Proocedings of VIIIth international conference on Turkish linguistics (pp. 127–137). Ankara University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuller, L. (2015). Clinical use of parental questionnaires in multilingual contexts. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (pp. 229–328). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Tuller, L., Delage, H., & Monjauce, C. (2011). Clitic pronoun production as a measure of typical language development in French: A comparative study of SLI, mild-to-moderate deafness and benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes. Lingua, 121, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuller, L., Hamann, C., Chilla, S., Ferré, S., Morin, E., Prévost, P., dos Santos, C., Ibrahim, L. A., & Zebib, R. (2018). Identifying language impairment in bilingual children in France and in Germany. International Journal Language Communication Disorders, 53, 888–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Türker, E. (2000). Turkish-Norwegian codeswitching. Evidence from intermediate and second generation Turkish immigrants in Norway. Unipub Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, S. (2016). Amount of exposure as a proxy for dominance in bilingual language acquisition. In C. Silva-Corvalán, & J. Teffers-Daller (Eds.), References 403 C. Language dominance in bilinguals (pp. 156–173). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzuntaş, A. (2008). Muttersprachliche sprachstandserhebung bei zweisprachigen türkischen kindern im deutschen kindergarten. In B. Ahrenholz (Ed.), Zweitspracherwerb: Diagnosen, verlaeufe, voraussetzungen (pp. 65–91). Fillibach Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann, A. (2020). Kasusmarkierung im Russischen und Deutschen. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, K., Schütze, C. T., & Rice, M. (1998). Subject case in children with SLI and unaffected controls: Evidence for the Agr/Tns omission model. Language Acquisition, 7(2–4), 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yağmur, K. (1997). First language attrition among Turkish speakers in Sydney. Tilburg University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yağmur, K., De Bot, K., & Korzilius, H. (1999). Language attrition, language shift and ethnolinguistic vitality of Turkish in Australia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 20(1), 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbay-Duman, T., Blom, E., & Topbaş, S. (2015). At the intersection of cognition and grammar: Deficits comprehending counterfactuals in Turkish children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 58, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarbay-Duman, T., & Topbaş, S. (2016). Epistemic uncertainty: Turkish children with specific language impairment and their comprehension of tense and aspect. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 51(6), 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, S. G. K., & O’Kearney, R. (2013). Emotional and behavioural outcomes later in childhood and adolescence for children with specific language impairments: Meta-analyses of controlled prospective studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 254(5), 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziethe, A., Eysholdt, U., & Doellinger, M. (2013). Sentence repetition and digit span: Potential markers of bilingual children with suspected SLI? Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 38(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ev | ev-ler |

| Accusative | ev-i | ev-ler-i |

| Dative | ev-e | ev-ler-e |

| Locative | ev-de | ev-ler-de |

| Ablative | ev-den | ev-ler-den |

| Genitive | ev-in | ev-ler-in |

| Instrumental | ev ile (ev-le) | ev-ler ile |

| (ev-ler-le) |

| Age | Case Marking | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1;3 | DAT | ACC | GEN | |||

| 1;4 | DAT | ACC | GEN | LOC | ||

| 1;5 | DAT | ACC | GEN | LOC | ABL | |

| 1;6 | DAT | ACC | GEN | LOC | ABL | INST |

| Background Variables (PaBiQ) | Germany | France | U.S. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BİTD (N = 38) | BİDLD (N = 12) | IL2_BITD (N = 10) | BİTD (N = 14) | BİDLD (N = 4) | BİTD (N = 5) | |

| Age (months) | 95.11 | 79.00 | 126.9 | 85.79 | 85.50 | 78.80 |

| (27.23) | (13.12) | (24.96) | (8.59) | (12.97) | (21.39) | |

| 49–161 | 64–111 | 86–149 | 70–99 | 67–95 | 61–108 | |

| L2 AoO | 18.87 | 25.92 | 97.20 | 7.07 | 6.0 | 19.20 |

| (16.31) | (13.75) | (25.42) | (13.40) | (12.0) | (19.63) | |

| 0–42 | 0–41 | 54–126 | 0–39 | 0–24 | 0–42 | |

| L2 LoE | 76.24 | 53.08 | 29.70 | 78.71 | 79.50 | 59.60 |

| (34.30) | (17.21) | (13.37) | (18.10) | (13.28) | (39.37) | |

| 13–161 | 29–81 | 9–54 | 31–99 | 67–95 | 20–108 | |

| % Early L1 Exposure | 67.89 | 75.42 | 94.90 | 72.36 | 78.50 | 87.60 |

| (20.11) | (12.01) | (8.33) | (12.17) | (5.20) | (11.67) | |

| 8–100 | 50–100 | 80–100 | 42–83 | 71–83 | 75–100 | |

| Current L1 richness (/14) | 5.68 | 6.50 | 9.50 | 7.57 | 6.50 | 7.20 |

| (2.46) | (2.11) | (2.42) | (1.45) | (4.04) | (3.83) | |

| 1–11 | 3–11 | 7–15 | 5–10 | 1–10 | 3–10 | |

| Current L1 Skills (/15) | 10.13 | 9.25 | 14.30 | 12.14 | 7.75 | 10.60 |

| (3.56) | (3.44) | (1.25) | (2.74) | (6.13) | (3.85) | |

| 0–15 | 2–15 | 11–15 | 6–15 | 0–14 | 6–14 | |

| Current L1 use (/16) | 9.08 | 9.83 | 12.10 | 11.36 | 11.75 | 9.60 |

| (3.03) | (2.12) | (2.47) | (1.50) | (1.50) | (2.19) | |

| 3–15 | 6–14 | 7–15 | 9–15 | 10–13 | 6–12 | |

| Item Types | Number of Item Types | Case Types and Possessive | Number of Obligatory Contexts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentence Repetition | 19 | Accusative | 10 | 35 |

| Dative | 6 | |||

| Locative | 0 | |||

| Ablative | 1 | |||

| Instrumental | 1 | |||

| Genitive | 5 | |||

| Possessive | 12 | |||

| Sentence Construction | 3 | Accusative | 1 | 4 |

| Dative | 1 | |||

| Locative | 0 | |||

| Ablative | 0 | |||

| Instrumental | 0 | |||

| Genitive | 1 | |||

| Possessive | 1 | |||

| Sentence Completion | 1 | Accusative | 0 | 1 |

| Dative | 0 | |||

| Locative | 1 | |||

| Ablative | 0 | |||

| Instrumental | 0 | |||

| Genitive | 0 | |||

| Possessive | 0 | |||

| Question–Answer | 2 | Accusative | 1 | 4 |

| Dative | 0 | |||

| Locative | 0 | |||

| Ablative | 0 | |||

| Instrumental | 0 | |||

| Genitive | 1 | |||

| Possessive | 2 | |||

| Interpretation | 4 | Accusative | 0 | 1 |

| Sentence Type | Sample Sentence | Number of Obligatory Contexts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Sentence | Baba-m | iş-e | git-ti. | Possessive (1) Dative (1) |

| father-1SG.POSS | work-DAT | go-PAST | ||

| “My father went to work”. | ||||

| Adverbial Clause | Çocuk-lar | cam-ı | kır-ıp | Accusative (1) |

| Child-P | window-ACC | break-VN(-Ip) | ||

| kaç-tı-lar. | ||||

| run away-PAST-3PL | ||||

| “Having broken the window, the children run away”. | ||||

| Noun Clause | Anahtar-ı | anne-m-e | ver-diğ-im-i | Accusative (2) Dative, (1) Possessive (1) |

| key-ACC | mother-POSS-DAT | give-FNOM- | ||

| 1SG.POSS-ACC | ||||

| unut-muş-um. | ||||

| forget-EV/PF-1SG | ||||

| “I forgot that I gave the key to my mother”. | ||||

| Relative Clause | Ağaç-a | tırman-an | kedi | Dative (1) Ablative (1) |

| Tree-DAT | climb-SUBJP | cat | ||

| köpek-ten | kaç-ıyor-du. | |||

| dog-ABLT | Run away-PROG-PAST | |||

| “The cat that climed the tree run away from the dog”. | ||||

| Adverbial Clause | Anne-m-le | baba-m | Instrumental (1) Possessive (2) | |

| Mother-1SG.POSS.INST | father-1POSS | |||

| konuş-ur-ken | biz | ders çalış-tı-k. | ||

| talk-AOR-CV | we | study-PAST-3PL | ||

| “As my mother and my father talked, we studied”. | ||||

| Simple Clause | Ayşe-nin | arkadaş-ı-nın | Genitive (3) Possessive (3) | |

| Ayşe-GEN | friend-3SG.POSS-GEN | |||

| bebek-i-nin | elbise-si | |||

| Doll- 3SG.POSS-GEN | cloth-3SG.POSS | |||

| mavi-y-di. | ||||

| blue-P.COP | ||||

| “The cloth of Ayse’s friend’s tool was blue”. | ||||

| Case and Possessive Conforming to Heritage Turkish but Not to Standard Turkish | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overextension of ablative | Expected response in standard Turkish: | ||||||

| Kitap | oku-ma-yı | ders-ten | daha çok | sev-er-im | |||

| Book | read-VN-ACC | lesson-ABL | more | like-AOR-1SG | |||

| “I like reading book more than lesson.” | |||||||

| Response of child BiTD HS (acceptable in heritage Turkish): | |||||||

| Kitap-tan | oku-ma-yı | ders-ten | daha çok | sev-er-im | |||

| Book-DAT | read-VN-ACC | lesson-ABL | more | like-AOR-1SG | |||

| “I like reading from book more than lesson.” | |||||||

| Substitution of accusative with dative | Expected response in standard Turkish (sentence repetition): | ||||||

| Dede-yi | sev-me-miş | ||||||

| grandfather-ACC | like-NEG-EV/PF | ||||||

| “S/he did not like the grandfather.” | |||||||

| Response of child BiTD (acceptable in heritage Turkish): | |||||||

| Dede-ye | sev-me-miş. | ||||||

| grandfather-DAT | like-NEG-EV/PF | ||||||

| “S/he did not like to the grandfather.” | |||||||

| Substitution of dative with accusative | Expected response in standard Turkish (sentence repetition): | ||||||

| Zeynep | ve | arkadaş-lar-ı-na | birşey | alı-yor-du. | |||

| Zeynep | and | friend-PL-3SG.POSS-DAT | something | buy-PRES.PROG-PAST | |||

| “S/he was buying something for Zeynep and her/his friends.” | |||||||

| Response of child BiTD and BiDLD HS (acceptable in heritage Turkish): | |||||||

| Zeynep | ve | arkadaş-lar-ı-nı | birşey | al-ıyor-du | |||

| Zeynep | and | friend-PL-ACC | something | buy-PRES.PROG-PAST | |||

| “S/he was buying something for Zeynep and her/his friends.” | |||||||

| Substitution of dative with locative | Expected response in standard Turkish (sentence repetition): | ||||||

| Sonra | dışarı | çık-ınca | araba-ya | eşya-lar-ı-nı | koy-uyor | ||

| And then | out | go-VN | car-DAT | belonging-PL-ACC | put-PRES.PROG | ||

| “And then when s/he goes out, s/he puts her/his belongins into the car.” | |||||||

| Response of child BiTD and BiDLD HS (acceptable in heritage Turkish): | |||||||

| Sonra | dışarı | çık-ınca | araba-da | eşya-lar-ı-nı | koy-uyor | ||

| And then | out | go-VN | car-LOC | belonging-PL-ACC | put-PRES.PROG | ||

| “And then when s/he goes out, s/he puts her/his belongins in the car.” | |||||||

| The use of instrumental marker ile "with" in -lEn (dialect leveling feature) | Expected response: | ||||||

| Mehmet | baba-sı | ile | balık tut-ma-ya | git-ti | |||

| Mehmet | father-3SG.POSS | with | angle | go-PAST | |||

| “Mehmet went to angle with his father.” | |||||||

| Response by adult and child HS BiTD (acceptable in heritage Turkish): | |||||||

| Mehmet baba-sın-lan | balık tut-ma-ya | git-ti. | |||||

| Mehmet father-3SG.POSS-INST | angle-DAT | go-PAST | |||||

| “Mehmet went to angle with his father.” | |||||||

| Omission of genitive in genitive–possessive construction | Expected response: | ||||||

| Ayşe-nin | arkadaş-ı-nın | bebeğ-i-nin | elbise-si | mavi-ydi | |||

| Ayşe-GEN | friend-ACC-GEN | doll-ACC-GEN | cloth-POSS | blue-P.COP | |||

| “The cloth of doll of Ayşe’s friend was blue.” | |||||||

| Response by adult and child HS BiTD/BiDLD (acceptable in heritage Turkish): | |||||||

| Ayşe-nin | arkadaş-ı-Ø | bebeğ-i-Ø | elbise-si | mavi-ydi | |||

| Ayşe-GEN | friend-ACC | doll-ACC | cloth-POSS | blue-P.COP | |||

| “The cloth of doll Ayşe friend was blue.” | |||||||

| Omission of possessive marker in genitive–possessive construction | Expected response: | ||||||

| Ben-im | arkadaş-ım | üç | gündür | hasta. | |||

| I-GEN | friend-POSS | tree | for tree days | sick | |||

| “My friend has been sich for tree days.” | |||||||

| Response HS BiTD (acceptable in heritage Turkish): | |||||||

| Ben-im | arkadaş-Ø | üç | gün | hasta | |||

| I-GEN | friend-Ø | tree | day | sick | |||

| “My friend has been sick tree days.” | |||||||

| Redundant use of possessive | Expected response: | ||||||

| Ev-i-ne | git-ti | ||||||

| home-3SG.DAT | go-PAST | ||||||

| “He went to his home.” | |||||||

| Response HS BiTD (acceptable in heritage Turkish): | |||||||

| Ev-i-si-ne git-ti. | |||||||

| home-3SG.POSS-3SG.POSS-DAT go-PAST | |||||||

| “He went to his his home.” | |||||||

| DLD Markers in Monolingual Turkish | |||||||

| Omission of accusative | Expected response | ||||||

| Anahtar-ı anne-m-e | verdi-ğim-i | unut-muş-um. | |||||

| Key-ACC mother-POSS-DAT | give-FNOM-ACC | forget-EV/PF-1SG | |||||

| “I forgot that I gave the key to my mother.” | |||||||

| Response by child HS BIDLD | |||||||

| Anahtar-Ø | anne-m-e | ver-diğ-im-Ø | unutmuşum | ||||

| key-Ø | mother-POSS-DAT | give-FNOM-ACC-Ø | forget-EV/PF-1SG | ||||

| “I forgot that I gave the key to my mother.” | |||||||

| Omission of dative | Expected response: | ||||||

| Dün | araba | adam-a | çarp-tı | ||||

| Yesterday | car | man-DAT | hit-PAST | ||||

| “The car hit the man yesterday.-“ | |||||||

| Response by child HS BiDLD: | |||||||

| Dün | araba | adam-Ø | çarp-tı | ||||

| Yesterday | car | man-Ø | hit-PAST | ||||

| “The car hit the man.” | |||||||

| Omission of locative | Expected Response: | ||||||

| Yarın | sınıf-ta | bayram | yok. | ||||

| Tomorrow | class-LOC | festival | exist-NEG | ||||

| “Tomorrow there is no festival in the class.” | |||||||

| Response by child HS BIDLD | |||||||

| Yarın | sınıf-Ø | bayram | yok. | ||||

| Tomorrow | class-Ø | festival | exist-NEG | ||||

| “Theres is no festival class.” | |||||||

| Group | %Target-like Case Clauses | |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Turkish Variety | ||

| Standard Turkish | Standard or Heritage Turkish | |

| Heritage_BİTD | 82.15 | 88.01 |

| (16.19) | (21.13) | |

| Heritage_BİDLD | 69.04 | 85.33 |

| (23.01) | (13.98) | |

| IL2_BİTD | 97.57 | 99.27 |

| (2.99) | (1.54) | |

| Group | %Target-like Case Clauses | |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Turkish Variety | ||

| Standard Turkish | Standard or Heritage Turkish | |

| χ2(2, N = 83) = 21.391 p < 0.001 | χ2(2, N = 83) = 14.183 p < 0.001 | |

| Heritage_BİTD vs. Heritage_BİDLD | U = 278.0 | U = 333.0 |

| p < 0.05 | p = 0.098 | |

| r = 0.077 | r = 0.038 | |

| Heritage_BİTD vs. IL2_BİTD | U = 67.0 | U = 98.5 |

| p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 | |

| r = 0.221 | r = 0.168 | |

| Heritage_BİDLD vs. IL2_BİTD | U = 7.5 | U = 24.0 |

| p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 | |

| r = 0.569 | r = 0.371 | |

| Country | Group | %Target-like Case Clauses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Turkish Variety | |||

| Standard Turkish | Standard or Heritage Turkish | ||

| Germany | Heritage_ BİTD | 80.04 | 87.95 |

| (17.94) | (20.76) | ||

| Heritage_ BİDLD | 67.79 | 84.28 | |

| (23.68) | (14.89) | ||

| IL2_BİTD | 97.57 | 99.27 | |

| (2.99) | (1.54) | ||

| France | Heritage_ BİTD | 87.39 | 88.68 |

| (10.37) | (25.38) | ||

| Heritage_ BİDLD | 72.80 | 88.48 | |

| (23.80) | (12.11) | ||

| U.S. | Heritage_ BİTD | 83.55 | 86.63 |

| (14.30) | (13.03) | ||

| Group | %Target-like Case Clauses | |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Turkish Variety | ||

| Standard Turkish | Standard or Heritage Turkish | |

| χ2(5, N = 83) = 23.194 p < 0.001 | χ2(5, N = 83) = 15.114 p < 0.001 | |

| Heritage_BİTD_G vs. Heritage_BİDLD_G | U = 147.0 | U = 164.0 |

| p = 0.07 | p = 0.140 | |

| r = 0.041 | r = 0.026 | |

| Heritage_BİTD_G vs. IL2_BİTD_G | U = 41.0 | U = 76.5 |

| p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 | |

| r = 0.379 | r = 0.236 | |

| Heritage_BİTD_G vs. Heritage_BİTD_F | U = 194.5 | U = 238.5 |

| p = 0.14 | p = 0.573 | |

| r = 0.042 | r = 0.006 | |

| Heritage_BİTD_G vs. Heritage_BİDLD_F | U = 58.0 | U = 63.0 |

| p = 0.468 | p = 0.572 | |

| r = 0.014 | r = 0.008 | |

| Heritage_BİTD_G vs. Heritage_BİTD_U.S. | U = 89.0 | U = 75.0 |

| p = 0.840 | p = 0.472 | |

| r = 0.001 | r = 0.014 | |

| Heritage_BİDLD_G vs. IL2_BİTD_G | U = 0.00 | U = 18.0 |

| p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 | |

| r = 0.720 | r = 0.398 | |

| Heritage_BİDLD_G vs. Heritage_BİTD_F | U = 31.0 | U = 50.0 |

| p < 0.05 | p = 0.085 | |

| r = 0.286 | r = 0.118 | |

| Heritage_BİDLD_G vs. Heritage_BİDLD_F | U = 23.5 | U = 19.5 |

| p = 0.953 | p = 0.599 | |

| r = 0.000 | r = 0.019 | |

| Heritage_BİDLD_G vs. Heritage_BİTD_U.S. | U = 18.0 | U = 28.5 |

| p = 0.234 | p = 0.879 | |

| r = 0.094 | r = 0.001 | |

| IL2_BİTD_G vs. Heritage_BİDLD_F | U = 16.5 | U = 16.0 |

| p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 | |

| r = 0.415 | r = 0.449 | |

| IL2_BİTD_G vs. Heritage_BİDLD_F | U = 7.5 | U = 6.0 |

| p = 0.076 | p = 0.054 | |

| r = 0.242 | r = 0.380 | |

| IL2_BİTD_G vs. Heritage_BİTD_U.S. | U = 9.5 | U = 6.0 |

| p = 0.055 | p < 0.05 | |

| r = 0.256 | r = 0.459 | |

| Heritage_BİTD_F vs. Heritage_BİDLD_F | U = 17.5 | U = 17.0 |

| p = 0.277 | p = 0.242 | |

| r = 0.069 | r = 0.076 | |

| Heritage_BİTD_F vs. Heritage_BİTD_U.S. | U = 30.5 | U = 26.0 |

| p = 0.687 | p = 0.444 | |

| r = 0.009 | r = 0.037 | |

| Heritage_BİDLD_F vs. Heritage_BİTD_U.S. | U = 6.5 | U = 9.5 |

| p = 0.413 | p = 0.905 | |

| r = 0.082 | r = 0.002 | |

| Background Variables (PaBiQ) | %Target-like Case Markers and Possessive Marker | |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Turkish Variety | ||

| Standard Turkish | Standard or Heritage Turkish | |

| L2 AoO | 0.430 * | 0.429 * |

| L2 LoE | −0.457 * | −0.382 * |

| % Early L1 Exposure | 0.256 * | 0.198 |

| Current L1 richness (/14) | 0.268 * | 0.247 * |

| Current L1 Skills (/15) | 0.352 * | 0.331 * |

| Current L1 use (/16) | 0.271 * | 0.119 |

| Country | Group | Background Variables (PaBiQ) | %Target-like Case Markers and Possessive Marker | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Turkish Variety | ||||

| Standard Turkish | Standard or Heritage Turkish | |||

| Germany | Heritage_ BITD | L2 AoO | 0.282 | 0.229 |

| L2 LoE | −0.362 | −0.262 | ||

| % Early L1 Exposure | 0.075 | 0.140 | ||

| Current L1 richness (/14) | −0.209 | −0.106 | ||

| Current L1 Skills (/15) | 0.144 | 0.175 | ||

| Current L1 use (/16) | 0.215 | −0.087 | ||

| Heritage_ BIDLD | L2 AoO | 0.229 | 0.231 | |

| L2 LoE | 0.295 | 0.410 | ||

| % Early L1 Exposure | 0.007 | −0.142 | ||

| Current L1 richness (/14) | −0.182 | 0.014 | ||

| Current L1 Skills (/15) | −0.530 | −0.053 | ||

| Current L1 use (/16) | −0.185 | 0.182 | ||

| IL2_BITD | L2 AoO | 0.643 * | 0.646 * | |

| L2 LoE | −0.597 | −0.182 | ||

| % Early L1 Exposure | −0.119 | 0.160 | ||

| Current L1 richness (/14) | 0.085 | 0.158 | ||

| Current L1 Skills (/15) | −0.007 | 0.005 | ||

| Current L1 use (/16) | −0.866 * | −0.557 | ||

| France | Heritage_ BITD | L2 AoO | 0.537 * | 0.698 * |

| L2 LoE | −0.461 | −0.741 * | ||

| % Early L1 Exposure | 0.294 | −0.027 | ||

| Current L1 richness (/14) | 0.303 | 0.470 | ||

| Current L1 Skills (/15) | −0.093 | −0.072 | ||

| Current L1 use (/16) | 0.151 | 0.298 | ||

| Heritage_ BIDLD | L2 AoO | 0.258 | 0.258 | |

| L2 LoE | - | - | ||

| % Early L1 Exposure | 0.632 | 0.632 | ||

| Current L1 richness (/14) | - | - | ||

| Current L1 Skills (/15) | - | - | ||

| Current L1 use (/16) | 0.105 | 0.105 | ||

| U.S. | Heritage_ BITD | L2 AoO | 0.975 * | 0.975 * |

| L2 LoE | −0.900 * | - | ||

| % Early L1 Exposure | −0.564 | −0.564 | ||

| Current L1 richness (/14) | 0.866 | 0.866 | ||

| Current L1 Skills (/15) | 0.667 | 0.564 | ||

| Current L1 use (/16) | 0.447 | 0.224 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Şan, N.H. Case Marking in Turkish Heritage Children With and Without Developmental Language Disorder. Languages 2025, 10, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050103

Şan NH. Case Marking in Turkish Heritage Children With and Without Developmental Language Disorder. Languages. 2025; 10(5):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050103

Chicago/Turabian StyleŞan, Nebiye Hilal. 2025. "Case Marking in Turkish Heritage Children With and Without Developmental Language Disorder" Languages 10, no. 5: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050103

APA StyleŞan, N. H. (2025). Case Marking in Turkish Heritage Children With and Without Developmental Language Disorder. Languages, 10(5), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050103