Kazakh–English Bilingualism in Kazakhstan: Public Attitudes and Language Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1: How is language choice distributed across different domains of communication in Kazakhstan?

- RQ2: What are public perceptions of Kazakh–English bilingualism, and how do these attitudes influence language policy in Kazakhstan?

- RQ3: What role do technological advancements and digital content play in the expansion of Kazakh language use?

2. Background Information

3. Language Policy and Planning in Kazakhstan

4. Kazakh–English Bilingualism: Policies and Practices

5. Methodology

5.1. Data Collection

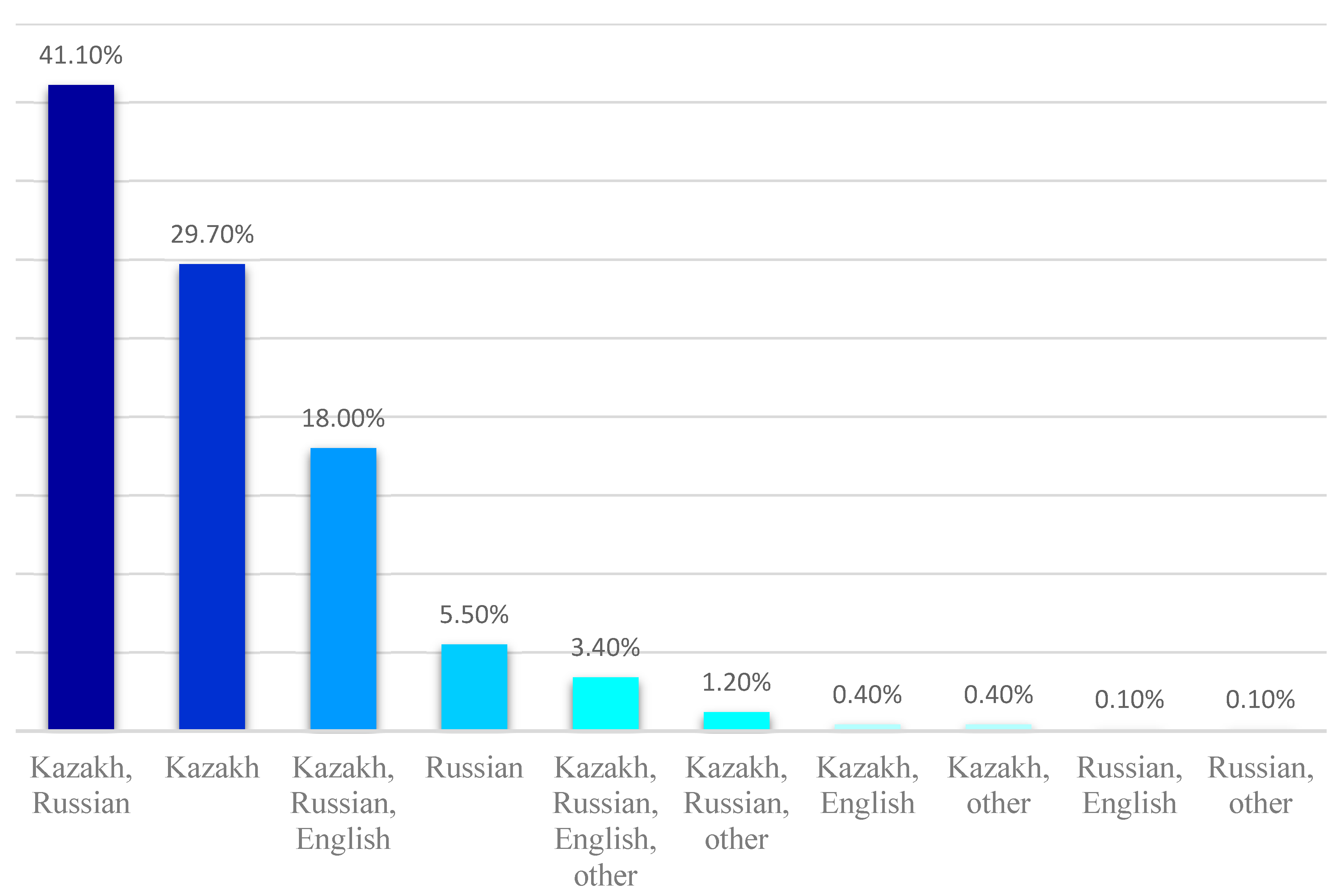

5.2. Participants

5.3. Data Analysis

6. Results

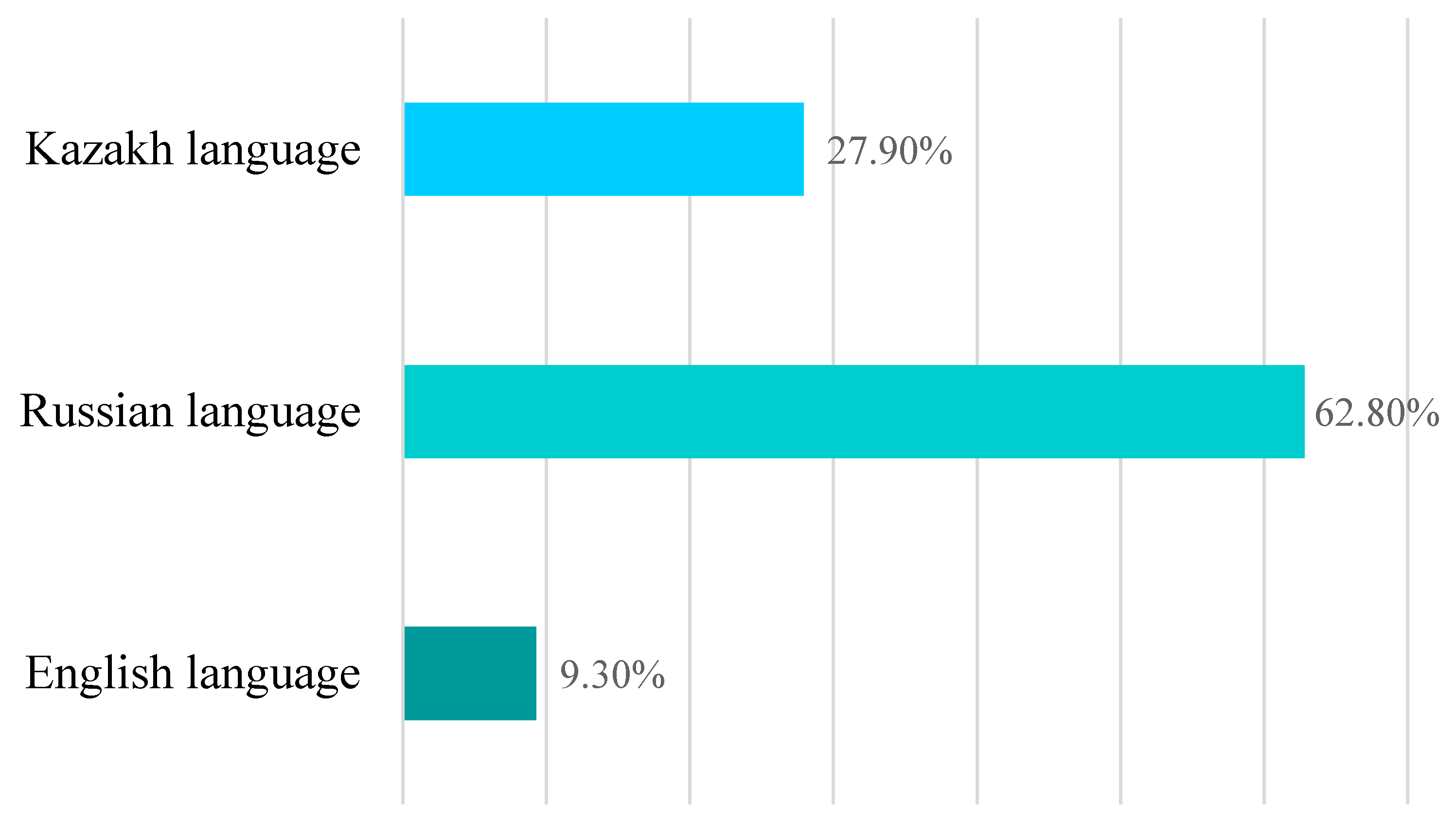

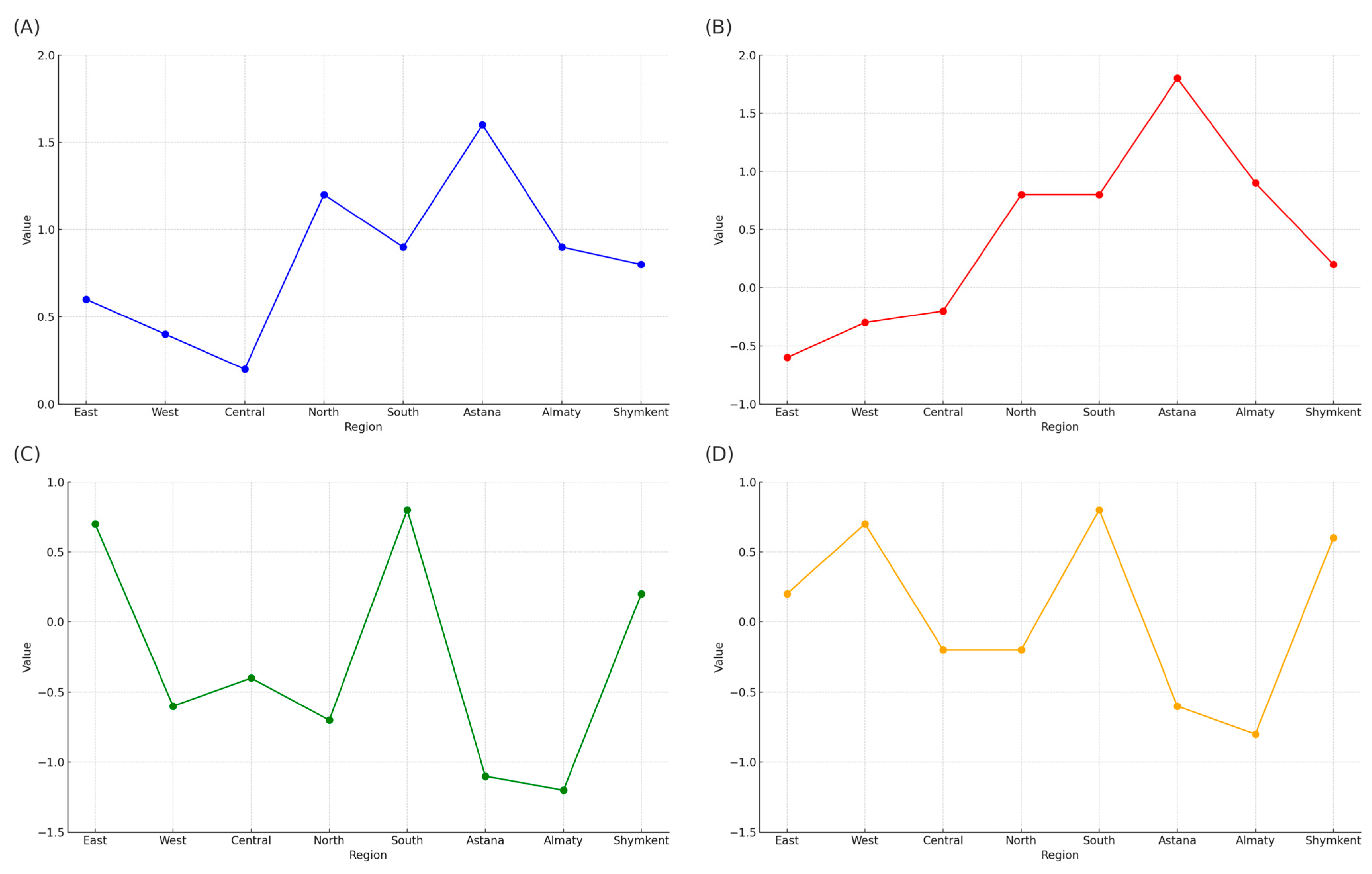

6.1. Language Preferences Across Various Settings

6.2. Public Attitudes Towards Kazakh–English Bilingualism

6.3. Kazakh Language and Its Integration in Modern Technologies

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abasilov, A., & Kapalbek, B. (2024). Linguistic dynamics and language policy in Kazakhstan: Challenges and future prospects. European Journal of Language Policy, 16(2), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency of Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan National Bureau of Statistics. (2024). Results of the 2024 population census of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: www.gov.kz (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Ahn, E. S., & Smagulova, J. (2022). English language choices in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. World Englishes, 41(1), 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batyrbekkyzy, G., Mahanuly, T. K., Tastanbekov, M. M., Dinasheva, L. S., Issabek, B., & Sugirbayeva, G. (2018). Latinization of Kazakh alphabet: History and prospects. European Journal of Science and Theology, 14, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- British International Haileybury Schools. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.haileybury.kz/ru (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Bureau of National Statistics. Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (n.d.). Available online: www.stat.gov.kz (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Chen, X. L., Zou, D., Xie, H. R., & Su, F. (2021). Twenty-five years of computer-assisted language learning: A topicmodeling analysis. Language Learning & Technology, 25(3), 151–185. Available online: https://www.lltjournal.org/item/10125-73454/ (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (1995). Available online: https://www.akorda.kz/en/constitution-of-the-republic-of-kazakhstan-50912 (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Coventry University’s Kazakhstan Branch. (n.d.). Available online: https://coventry.edu.kz/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Ferrer, A., & Lin, T. B. (2024). Official bilingualism in a multilingual nation: A study of the 2030 bilingual nation policy in Taiwan. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(2), 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2019). State program for the implementation of language policy in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2020–2025. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P1900001045 (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Heriot-Watt University’s Aktobe Branch. (n.d.). Available online: http://zhubanov.edu.kz (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- International Miras School. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.miras.kz/kk (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Karabassova, L. (2020). Understanding trilingual education reform in Kazakhstan: Why is it stalled? In Education in central Asia: A kaleidoscope of challenges and opportunities (pp. 37–51). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kazakhstan. (n.d.-a). Geographical profile. Union of International Associations. Available online: https://uia.org/s/geo/en/1400000129 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Kazakhstan. (n.d.-b). Kazakhstan: A country profile; The Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/uploads/2022/6/21/cd9b96fe6b95dc380c88dade8fae93d2_original.61045758.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Kazakhstan. (n.d.-c). Kazakhstan population. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/kazakhstan-population/ (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Koptleuova, K., Karagulova, B., Zhumakhanova, A., Kondybay, K., & Salikhova, A. (2023). Multilingualism and the current language situation in the Republic of Kazakhstan. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 11(3), 242–257. [Google Scholar]

- Law On Languages in the Republic of Kazakhstan. (1997). Available online: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=1049836 (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Ministry of Culture and Sports of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2017). Within the framework of the “Rukhani Zhangyru” program: “New Humanitarian Knowledge. 100 New Textbooks in Kazakh” project. Available online: https://openu.kz/kz/books (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Navarro, J. L., & Tudge, J. R. H. (2023). Technologizing bronfenbrenner: Neo-ecological theory. Current Psychology, 42(22), 19338–19354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarbayev, N. (2007). The address of the president of the Republic of Kazakhstan “New Kazakhstan in the New World”. Available online: https://www.akorda.kz/en/addresses/addresses_of_president/address-of-the-president-of-the-republic-of-kazakhstan-nursultan-nazarbayev-to-the-people-of-kazakhstan-february-28-2007 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Presentation of the Oxford Qazaq Dictionary. (2023). Available online: https://nu.edu.kz (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Reagan, T. (2019). Language planning and language policy in Kazakhstan. In The Routledge international handbook of language education policy in Asia (pp. 442–451). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smagulova, J. (1996). On the principles of language policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan. In Main legislative documents on languages in the Republic of Kazakhstan (pp. 11–17). Jurist. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, B. (2009). Language management. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsay, Y. N., & Pagnueva, A. S. (2011). To the problem of “Trinity of languages” cultural project realization in the republic of Kazakhstan. Education and Science Without Borders, 2(4), 82. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y. (2022). Toward technology-based education and English as a foreign language motivation: A review of literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 870540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R., & Zou, D. (2022). A state-of-the-art review of the modes and effectiveness of multimedia input forsecond and foreign language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(9), 2790–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkynbekova, S., & Aimoldina, A. (2023). The impact of socio-cultural context on composing business letters in modern Kazakhstani business community: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 52(1), 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkynbekova, S., Ayupova, G., Galiyeva, B., Shakhputova, Z., & Zabrodskaja, A. (2025). Ethno-linguistic identity of Kazakhstani student youth in modern multinational context of Kazakhstan (sociolinguistic analysis of empirical research). Languages, 10(2), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Geographical Distribution | ||

| Northern Kazakhstan | 138 | 13.8 |

| Southern Kazakhstan | 254 | 25.4 |

| Western Kazakhstan | 164 | 16.4 |

| Eastern Kazakhstan | 55 | 5.5 |

| Central Kazakhstan | 79 | 7.9 |

| Almaty | 104 | 10.4 |

| Astana | 128 | 12.8 |

| Shymkent | 78 | 7.8 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–25 | 350 | 35 |

| 26–35 | 358 | 35.8 |

| 36–45 | 192 | 19.2 |

| 46–60 | 91 | 9.1 |

| 60–63 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 312 | 31.2 |

| Female | 688 | 68.8 |

| Ethnic composition | ||

| Kazakh | 914 | 91.4 |

| Russian | 61 | 6.1 |

| Other minorities | 25 | 2.5 |

| Social status | ||

| Students | 219 | 21.9 |

| Private Sector Employees | 326 | 32.6 |

| Public Sector Employees | 133 | 13.3 |

| Retirees | 11 | 1.1 |

| Unemployed | 123 | 13.2 |

| Homemakers | 118 | 11.8 |

| Entrepreneurs | 61 | 6.1 |

| Field of Education | ||

| Education | 249 | 24.9 |

| Humanities | 116 | 11.6 |

| Service Sector | 107 | 10.7 |

| Medicine and Healthcare | 107 | 10.7 |

| Manufacturing and Industry | 99 | 9.9 |

| Finance and Business | 88 | 8.8 |

| Information Technology | 68 | 6.8 |

| Science and Research | 49 | 4.9 |

| Arts | 42 | 4.2 |

| Law | 22 | 2.2 |

| Tourism | 1 | 0.1 |

| Sport | 1 | 0.1 |

| No formal education | 51 | 5.1 |

| Languages | Kaz | Rus | Eng | Kaz, Rus | Kaz, Eng | Rus, Eng | Kaz, Rus, Eng |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education, % | 51.3 | 15.1 | 1.8 | 18.4 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 9.9 |

| At work, % | 42.3 | 19.2 | 1.4 | 27.9 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 4.3 |

| At home, % | 66.5 | 12.9 | 0.5 | 19.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| With friends, % | 54.4 | 12.5 | 0.4 | 29.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| In government institutions, % | 49.3 | 21.4 | 0.2 | 27.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| In public places, % | 44.4 | 21.2 | 0.7 | 31.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| When using the internet and social media, % | 32.9 | 25.4 | 1.2 | 29.3 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 7.8 |

| When watching television, % | 44.7 | 15.7 | 1.7 | 34.3 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 2.2 |

| When reading fiction, % | 49.5 | 25.9 | 1.8 | 17.1 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 4.1 |

| When reading scientific literature, % | 34.9 | 38.8 | 3.3 | 14.2 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 4.6 |

| When conducting banking operations, % | 31.2 | 41.5 | 1.1 | 23.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 2.2 |

| Regions of Kazakhstan | Kazakh Language | Russian Language | English Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Kazakhstan | −0.9 | 0.9 | −0.8 |

| West Kazakhstan | 0.7 | −0.2 | −1.3 |

| Central Kazakhstan | −0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| North Kazakhstan | −1.6 | 1.4 | −0.1 |

| South Kazakhstan | 2.2 | −1 | −2.8 |

| Astana | −2.4 | 0.5 | 2.1 |

| Almaty | 0.2 | −0.5 | 1 |

| Shymkent | 1.6 | −1.2 | −0.6 |

| Statement | Chi-Square (χ2) | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Significance Level (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I support the policy of promoting English through education | 54,181 | 28 | 0.002 < 0.05 |

| Supporting English contributes to strengthening the position of Kazakh | 62,947 | 28 | 0.001 < 0.05 |

| Promoting English poses a threat to the future of Kazakh language and culture | 62,294 | 28 | 0.002 < 0.05 |

| The popularity of English reduces interest in the Kazakh language | 90,009 | 28 | 0.001 < 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tlepbergen, D.; Akzhigitova, A.; Zabrodskaja, A. Kazakh–English Bilingualism in Kazakhstan: Public Attitudes and Language Practices. Languages 2025, 10, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050102

Tlepbergen D, Akzhigitova A, Zabrodskaja A. Kazakh–English Bilingualism in Kazakhstan: Public Attitudes and Language Practices. Languages. 2025; 10(5):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050102

Chicago/Turabian StyleTlepbergen, Dinara, Assel Akzhigitova, and Anastassia Zabrodskaja. 2025. "Kazakh–English Bilingualism in Kazakhstan: Public Attitudes and Language Practices" Languages 10, no. 5: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050102

APA StyleTlepbergen, D., Akzhigitova, A., & Zabrodskaja, A. (2025). Kazakh–English Bilingualism in Kazakhstan: Public Attitudes and Language Practices. Languages, 10(5), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050102