Breaking Down Greek Nominal Stems: Theme and Nominalizer Exponents

Abstract

1. Introduction

| (1) | a. | ánθropo-s | ‘human.MASC-SG.NOM’ |

| (2) | a. | pórta-Ø | ‘door.FEM-SG.NOM/ACC’3 |

| b. | pórt-es | ‘door.FEM-PL.NOM/ACC’ | |

| (3) | a. | psará-s | ‘fisherman.MASC-SG.NOM’ |

| b. | psaráð-es | ‘fisherman.MASC-PL.NOM/ACC’ |

| (4) | a. | karékla-Ø | ‘chair.FEM-SG.NOM/ACC’ |

| b. | karékl-es | ‘chair.FEM-PL.NOM/ACC’ | |

| (5) | a. | babá-s | ‘dad.MASC-SG.NOM’ |

| b. | babáð-es | ‘dad.MASC-PL.NOM/ACC’ | |

| (6) | a. | máθima-Ø | ‘lesson.NEUT-SG.NOM/ACC’ |

| b. | maθímat-a | ‘lesson.NEUT-PL.NOM/ACC’ |

2. Distribution of Stem Endings

2.1. Stem-Final /o/, /a/, /i/

| (7) | a. | ðáskalo-s | ‘teacher.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: ðáskal-i |

| b. | uranó-s | ‘sky.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: uran-í | |

| c. | ípiro-s | ‘continent.FEM-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: ípir-i | |

| d. | leofóro-s | ‘avenue.FEM-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: leofór-i | |

| e. | átomo-Ø | ‘person.NEUT-SG.NOM/ACC’ | cf. PL: átom-a | |

| f. | biskóto-Ø | ‘biscuit.NEUT-SG.NOM/ACC’ | cf. PL: biskót-a |

| (8) | a. | ðaskála-Ø | ‘teacher.FEM-SG.NOM/ACC’ | cf. PL: ðaskál-es |

| b. | aɣorá-Ø | ‘market.FEM-SG.NOM/ACC’ | cf. PL: aɣor-és | |

| c. | fílaka-s | ‘guard.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: fílak-es | |

| d. | kanóna-s | ‘rule.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: kanón-es | |

| (9) | a. | aðerfí-Ø | ‘sister.FEM-SG.NOM/ACC’ | cf. PL: aðerf-és |

| b. | záxari-Ø | ‘sugar.FEM-SG.NOM/ACC’ | cf. PL: záxar-es | |

| c. | aθlití-s | ‘athlete.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: aθlit-és | |

| d. | planíti-s | ‘planet.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: planít-es |

2.2. Stem-Final /a(ð)/, /i(ð)/, /a(t)/

| (10) | a. | vasiljá-s | ‘king.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: vasiljáð-es |

| b. | papá-s | ‘priest.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: papáð-es | |

| (11) | a. | manávi-s | ‘grocer.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: manávið-es |

| b. | serífi-s | ‘sheriff.MASC-SG.NOM’ | cf. PL: serífið-es |

| (12) | a. | pírama-Ø | ‘experiment.NEUT-SG.NOM/ACC’ | cf. PL: pirámat-a |

| b. | máθima-Ø | ‘lesson.NEUT-SG.NOM/ACC’ | cf. PL: maθímat-a |

3. Morphosyntactic Analysis

3.1. Distributed Morphology

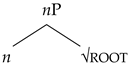

| (13) |  |

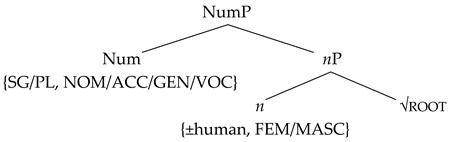

| (14) |  |

| (15) | a. | n[+human, FEM] |

| b. | n[FEM] | |

| c. | n[+human, MASC] | |

| d. | n[MASC] | |

| e. | n[–human] | |

| f. | n |

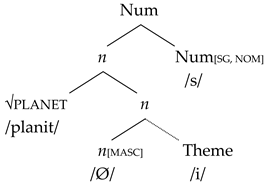

| (16) |  |

| (17) |  |

3.2. n Exponents

| (18) |  |

| (19) |  |

| (20) |  |

3.3. Theme Exponents

| (21) |  |

| (22) |  |

| (23) |  |

| (24) |  |

4. Phonological Analysis

4.1. Segmental Representation

| (25) | /at0.7/ | Dep weight: 2 | Max weight: 1 | |

| a. | [at1] | −(1 − 0.7) × 2 = −0.6 | ||

| b. | [a] | −(0.7 × 1) = −0.7 |

| (26) | /at0.7/ | Dep weight: 2 | Max weight: 1 | *C[–son, –cont]]ω weight: 1 | H | |

| a. | [at1]19 | −(1 − 0.7) × 2 = −0.6 | −1 | −1.6 | ||

| b. | [a] | −(0.7 × 1) = −0.7 | −0.7 |

| (27) | /piram-at0.7-a/ | Dep weight: 2 | Max weight: 1 | *VV weight: 1 | H | |

| a. | [piˈramata] | −(1 − 0.7) × 2 = −0.6 | −0.6 | |||

| b. | [piˈramaa] | −(0.7 × 1) = −0.7 | −1 | −1.7 |

| (28) | /pap-að0.7-s/ | Dep weight: 2 | Max weight: 1 | *CC]ω weight: 2 | H | |

| a. | [paˈpaðs] | −(1 − 0.7) × 2 = −0.6 | −2 | −2.6 | ||

| b. | [paˈpas] | −(0.7 × 1) = −0.7 | −0.7 |

| (29) | /pap-að0.7-es/ | Dep weight: 2 | Max weight: 1 | *VV weight: 1 | H | |

| a. | [paˈpaðes] | −(1 − 0.7) × 2 = −0.6 | −0.6 | |||

| b. | [paˈpaes] | −(0.7 × 1) = −0.7 | −1 | −1.7 |

| (30) | /θalas-a0.7/ | Dep weight: 2 | Max weight: 1 | *VV weight: 1 | H | |

| a. | [ˈθalasa] | −(1 − 0.7) × 2 = −0.6 | −0.6 | |||

| b. | [ˈθalas] | −(0.7 × 1) = −0.7 | −0.7 | |||

| (31) | /θalas-a0.7-es/ | Dep weight: 2 | Max weight: 1 | *VV weight: 1 | H | |

| a. | [θaˈlasaes] | −(1 − 0.7) × 2 = −0.6 | −1 | −1.6 | ||

| b. | [ˈθalases] | −(0.7 × 1) = −0.7 | −0.7 |

4.2. Stress

| (32) | (* .) að0.7 - σ |

| (33) | (* .) σ - ið0.7 |

| (34) | (* .) σ σ - at0.7 |

5. Discussion

| (35) | a. | papa- | ~ | papað |

| b. | manavi- | ~ | manavið | |

| c. | pirama- | ~ | piramat- |

| (36) | a. | urano- | ~ | uran |

| b. | θalasa- | ~ | θalas | |

| c. | planiti- | ~ | planit- |

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Accusative |

| AL | Activity Level |

| ALex | Annotated-Lexicon |

| APU | Antepenultimate |

| C | Consonant |

| DM | Distributed Morphology |

| FEM | Feminine |

| GEN | Genitive |

| GHG | Gradient Harmonic Grammar |

| H | Harmony |

| MASC | Masculine |

| n | Nominalizer |

| NEUT | Neuter |

| NOM | Nominative |

| Num | Number |

| PL | Plural |

| PU | Penultimate |

| REF | Referentiality |

| SG | Singular |

| TC | Tagged-Clean |

| U | Ultimate |

| V | Vowel |

| VOC | Vocative |

| 1 | We define as “stem” the part of the nominal form that results if we remove any number/case exponents (cf. Anastassiadis-Symeonidis, 2012; Ralli, 2022). |

| 2 | Here, we exclude phenomena of a phonological nature that may be attested at the left edge of the nominal form, as, for example, assimilation of stops after nasals (e.g., /tin porta/ → [timˈboɾta], ‘the door’; see Revithiadou & Markopoulos, 2021). |

| 3 | All neuter and most feminine nouns have a syncretic nominative-accusative-vocative form. To ease the readability of the examples, we omit the vocative case in glosses. |

| 4 | The term permissible echoes the trisyllabic window restriction in Greek, i.e., the requirement that stress may fall on only one of the last three syllables of the word (Malikouti-Drachman & Drachman, 1989; Drachman & Malikouti-Drachman, 1999; Revithiadou, 1999, 2007). |

| 5 | There are also neuter nouns that, at the surface level, have a stem ending in -i (e.g., spíti-Ø ‘house.NEUT-SG.NOM/ACC’; psomí-Ø ‘bread.NEUT-SG.NOM/ACC’). However, the different allomorphy pattern that is attested in these nouns (e.g., /spitj-a/ [ˈspitça] ‘house.NEUT-PL.NOM/ACC’; /psomj-a/ [psoˈmɲa] ‘bread.NEUT-PL.NOM/ACC’) suggests that the surface stem-final /i/ in fact corresponds to an underlying /j/ (see Markopoulos, 2018; Apostolopoulou, 2018). |

| 6 | The pattern -i/-ið emerges exclusively in masculine human nouns. The pattern -á/-áð is also attested in a handful of feminine nouns (e.g., mamá ‘mom (SG)’, cf. mamáð-es (PL)) and in a closed class of Turkish non-human loanwords (e.g., kuvá-s ‘bucket (SG)’, cf. kuváð-es (PL)). |

| 7 | Νouns with stem-final /i(ð)/ that include the derivational suffixes -dz and -l are always stressed on the last syllable of the stem (e.g., taksi-dz-í-s ‘taxi driver (SG)’, cf. taksi-dz-íð-es (PL); merak-l-í-s ‘a person keen on something (SG)’, cf. merak-l-íð-es (PL)). Here we consider only non-derived nouns; therefore, this noun category is excluded. |

| 8 | When the singular form consists of two syllables, it receives stress on the leftmost one, i.e., on PU (e.g., kíma ‘wave (SG)’). |

| 9 | Apart from DM, the decomposition of a stem into separate constituents could also be formalized within other syntax-oriented frameworks such as the Exo-Skeletal Model (Borer, 2005a, 2005b, 2013), Spanning (Svenonius, 2012), Nanosyntax (Starke, 2009), or Morphology as Syntax (Collins & Kayne, 2023). Of course, the implementation would require framework-specific adjustments in each case. For instance, in a nanosyntactic account, the root and n nodes would break down into a sequence of functional heads. To give a brief example, the structure of a feminine nominal stem could be the following: [FEM [CLASS REF]] (see Caha, 2025, to appear). I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing up this issue. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | In Greek, the n node has also been argued to host (post-syntactic) declension class features (Alexiadou, 2017; Alexiadou & Anagnostopoulou, 2023; see also Kramer, 2015), as well as Number features in idiosyncratic plural forms of, e.g., mass nouns, such as ner-á, ‘water-PL’ (Alexiadou, 2011; see also Lecarme, 2002; Acquaviva, 2008; Lowenstamm, 2008; Kramer, 2016; Punske & Jackson, 2017). Many thanks to an anonymous reviewer for raising this point. |

| 12 | Here we remain agnostic about the (non-)content of roots. To enhance the clarity of the examples, in the remainder of the article, we refer to roots using abstract meanings written in small caps. This choice, however, should not be interpreted as a particular approach to the nature of roots. For some discussion, see, among others, Arad (2005); Acquaviva (2009); Borer (2013); Alexiadou et al. (2014); Harley (2014); Panagiotidis (2014, 2020). |

| 13 | Given that the inflectional suffix -es in pap-áð-es and manáv-ið-es and the suffix -a in pirám-at-a are underspecified for case (they may appear in nominative, accusative, or vocative plural forms), they are taken to be elsewhere PL exponents. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | The Theme node is also present in the syntactic structures in (18–20) but has a zero exponent. |

| 16 | Revithiadou and Spyropoulos (2016) also highlight the distinction between, on the one hand, /o/, /a/, and /i/, and, on the other hand, /að/, /ið/, and /at/, but propose that both categories of stem endings are Theme exponents. The Theme node that is realized by the former category does not attach to the n node, but to a functional category F higher in the structure. |

| 17 | Alternatively, this hypothesis could be framed within an analysis positing floating segments (e.g., Faust, 2014; Scheer, 2016). |

| 18 | Throughout this section, a subscript number is used to indicate the AL of an element. |

| 19 | In theory, in each computation there is an infinite number of possible outputs. In the present analysis, we focus only on the top two candidates, one where the weak segment is realized and one where it is not pronounced. |

| 20 | In the present study, AL values are assigned arbitrarily and simply serve as indicators of the elements’ relative strength. For some approaches to calculating AL using lexical databases, see Markopoulos & Frantzi (2022) and Markopoulos et al. (2024). |

| 21 | ALex is based on Anastassiadis-Symeonidis’ (2002) Reverse Dictionary of Modern Greek and consists of 5,133 nouns (types). TC is based on Protopapas et al.’s (2012) Clean Corpus and includes 22,806 nominal forms (types and tokens) (Apostolouda, 2018, p. 164). |

| 22 | Within the framework of GHG, this would translate into AL lower than 1. A detailed GHG account of stress assignment is beyond the scope of the present article. For an analysis that captures the probabilistic nature of stress assignment in Greek nouns, see Markopoulos et al. (2024). |

| 23 | |

| 24 | I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for bringing up this discussion. |

References

- Acquaviva, P. (2008). Lexical plurals: A morphosemantic approach. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Acquaviva, P. (2009). Roots and lexicality in Distributed Morphology. York Papers in Linguistics (Series 2), 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, A. (2011). Plural mass nouns and the morpho-syntax of number. In M. B. Washburn, K. McKinney-Bock, E. Varis, A. Sawyer, & B. Tomaszewicz (Eds.), Proceedings of the 28th west coast conference on formal linguistics (pp. 33–41). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, A. (2017). Gender and nominal ellipsis. In N. LaCara, K. Moulton, & A.-M. Tessier (Eds.), “A schrift to fest kyle johnson” (Vol. 1, pp. 11–22). Linguistics Open Access Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, A., & Anagnostopoulou, E. (2023). Zero-derived nouns in Greek. Languages, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiadou, A., Borer, H., & Schäfer, F. (2014). The syntax of roots and the roots of syntax. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, A., Haegeman, L., & Stavrou, M. (2007). Noun phrase in the generative perspective. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Anastassiadis-Symeonidis, A. (2002). Aντίστροφο λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής [Reverse dictionary of Modern Greek]. Institute of Modern Greek Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Anastassiadis-Symeonidis, A. (2012). Το νεοελληνικό κλιτικό σύστημα των ουσιαστικών και οι τάσεις του [The Modern Greek noun inflectional system and its tendencies]. In Z. Gavriilidou, A. Efthymiou, E. Thomadaki, & P. Kambakis-Vougiouklis (Eds.), Selected papers of the 10th international conference of Greek linguistics (pp. 23–40). Democritus University of Thrace. [Google Scholar]

- Anastassiadis-Symeonidis, A., & Cheila-Markopoulou, D. (2003). Συγχρονικές και διαχρονικές τάσεις στο γένος της Ελληνικής (Μια θεωρητική πρόταση) [Synchronic and diachronic tendencies in Greek gender (A theoretical proposal)]. In A. Anastassiadis-Symeonidis, A. Ralli, & D. Cheila-Markopoulou (Eds.), Το γένος [Gender] (pp. 13–56). Patakis. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolopoulou, E. (2018). H φωνολογική αναπαράσταση του ημιφώνου της Κοινής Νέας Ελληνικής: Μια προσέγγιση με βάση τη Διαβαθμισμένη Aρμονική Γραμματική [The phonological representation of glide in Standard Modern Greek: An approach based on Gradient Harmonic Grammar] [Master’s Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki]. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolouda, V. (2012). O τονισμός των ουσιαστικών της Ελληνικής: Μια πειραματική προσέγγιση [The stress of Greek nouns: An experimental approach] [Master’s Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki]. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolouda, V. (2018). Πειραματικές διερευνήσεις στον τονισμό της Ελληνικής [Experimental investigations on Greek stress] [Ph.D. Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki]. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, M. (2005). Roots and patterns: Hebrew morpho-syntax. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, G. (1997). Allomorphy and the autonomy of morphology. Folia Linguistica, 31(1–2), 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borer, H. (2005a). In name only: Structuring sense (Vol. I). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borer, H. (2005b). The normal course of events: Structuring sense (Vol. II). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borer, H. (2013). Taking form: Structuring sense (Vol. III). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caha, P. (2025). Root and stem allomorphy without multiple exponence: The case of special nominatives. Morphology. Published online 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caha, P. (to appear). Nanosyntax: Some key features. In A. Alexiadou, R. Kramer, A. Marantz, & I. Oltra-Massuet (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of distributed morphology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christofidou, A. (2003). Γένος και κλίση στην Ελληνική (Μια φυσική προσέγγιση) [Gender and inflection in Greek (A natural approach)]. In A. Anastassiadis-Symeonidis, A. Ralli, & D. Cheila-Markopoulou (Eds.), Το γένος [Gender] (pp. 100–131). Patakis. [Google Scholar]

- Clairis, C., & Babiniotis, G. (2004). Γραμματική της Νέας Ελληνικής: Δομολειτουργική-επικοινωνιακή [Grammar of modern Greek: Structural-functional-communicative]. Ellinika Grammata. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C., & Kayne, R. S. (2023). Towards a theory of morphology as syntax. Studies in Chinese Linguistics, 44(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drachman, G., & Malikouti-Drachman, A. (1999). Greek word accent. In H. van der Hulst (Ed.), Word prosodic systems in the languages of Europe (pp. 897–945). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, D. (2010). Localism versus globalism in morphology and phonology. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, D., & Noyer, R. (2007). Distributed Morphology and the syntax-morphology interface. In G. Ramchand, & C. Reiss (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces (pp. 289–324). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faust, N. (2014). Where it’s [at]: A phonological effect on phasal boundaries in the construct state of Modern Hebrew. Lingua, 150, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, N., & Smolensky, P. (2017). Activity as an alternative to autosegmental association [Unpublished manuscript]. Université Paris 8 CNRS/SFL & Johns Hopkins University. [Google Scholar]

- Fábregas, A. (2017). Theme vowels are verbs. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Galani, A. (2003). An analysis of theme vowels in Modern Greek within Distributed Morphology. Interlingüística, 14, 399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Galani, A. (2005). The morphosyntax of verbs in Modern Greek [Ph.D. Thesis, University of York]. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). Distributed Morphology and the pieces of inflection. In K. Hale, & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger (pp. 111–176). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1994). Some key features of Distributed Morphology. In A. Carnie, & H. Harley (Eds.), MIT working papers in linguistics 21: Papers on phonology and morphology (pp. 275–288). MITWPL. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, M., & Nevins, A. (2009). Rule application in phonology. In E. Raimy, & C. E. Cairns (Eds.), Contemporary views on architecture and representations in phonology (pp. 355–382). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, H. (2014). On the identity of roots. Theoretical Linguistics, 40(3–4), 225–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, H., & Noyer, R. (1999). Distributed Morphology. Glot International, 4(4), 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, D., Mackridge, P., Philippaki-Warburton, I., & Spyropoulos, V. (2012). Greek: A comprehensive grammar (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, B. (2022). Gradient symbolic representations in Harmonic Grammar. Language and Linguistics Compass, 16(9), e12473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, P. (2007). Radical decomposition and argument structure [Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tromsø]. [Google Scholar]

- Karasimos, A. (2011). Υπολογιστική επεξεργασία της αλλομορφίας στην παραγωγή λέξεων της Ελληνικής [Computational processing of allomorphy in Greek word derivation] [Ph.D. Thesis, University of Patras]. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, R. S. (2016). What is suppletive allomorphy? On went and on *goed in English [Unpublished manuscript]. New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Kihm, A. (2005). Noun class, gender, and the lexicon-syntax-morphology interfaces. In G. Cinque, & R. S. Kayne (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax (pp. 459–512). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačević, P., Antonyuk, S., & Quaglia, S. (2022). The status of verbal theme vowels in contemporary linguistic theorizing: Some recent developments. An introduction. Glossa, 9(1), 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R. (2015). The morphosyntax of gender. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, R. (2016). A split analysis of plurality: Number in Amharic. Linguistic Inquiry, 47(3), 527–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecarme, J. (2002). Gender “polarity”: Theoretical aspects of Somali nominal morphology. In P. Boucher, & M. Plénat (Eds.), Many morphologies (pp. 109–141). Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstamm, J. (2008). On little n, √, and types of nouns. In J. Hartmann, V. Hegedus, & H. van Riemsdijk (Eds.), Sounds of silence: Empty elements in syntax and phonology (pp. 105–144). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Malikouti-Drachman, A., & Drachman, G. (1989). Τονισμός στα Ελληνικά [Stress in Greek]. Studies in Greek Linguistics, 9, 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Marinis, M. (2019). Κλίση και οργάνωση κλιτικών παραδειγμάτων [Inflection and organization of inflectional paradigms] [Ph.D. Thesis, University of Patras]. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, G. (2018). Phonological realization of morphosyntactic features [Ph.D. Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki]. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, G. (2021). Nominal inflection in the morphosyntax-phonology interface: A comparative study of Greek and Hebrew. In T. Markopoulos, C. Vlachos, A. Archakis, D. Papazachariou, A. Roussou, & G. J. Xydopoulos (Eds.), Proceedings of the ICGL14 (pp. 792–801). University of Patras. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, G. (2023). Το ονοματικό σύστημα της Ελληνικής [The nominal system of Greek]. In D. Papadopoulou, & A. Revithiadou (Eds.), Εισαγωγή στη μορφολογία [Introduction to morphology] (pp. 116–149). Institute of Modern Greek Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, G., & Apostolopoulou, E. (2022). Vowel height as sonority level. In A.-M. Sougari, & V. Bardzokas (Eds.), Selected papers on theoretical and applied linguistics from ISTAL 24 (pp. 513–529). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, G., & Frantzi, K. (2022). Investigating stem allomorphy in Greek and Arabic by means of lexical frequency. In A.-M. Sougari, & V. Bardzokas (Eds.), Selected papers on theoretical and applied linguistics from ISTAL 24 (pp. 530–545). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, G., Apostolopoulou, E., Apostolouda, V., & Revithiadou, A. (2024). Beyond unpredictability: A GHG analysis of Greek noun stress. In S. Phadnis, C. Spellerberg, & B. Wilkinson (Eds.), Proceedings of the fifty-fourth annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society (NELS 54) (Vol. 2, pp. 61–74). GLSA. [Google Scholar]

- Oltra-Massuet, I. (1999). On the notion of theme vowel: A new approach to Catalan verbal morphology [Master’s Thesis, MIT]. [Google Scholar]

- Oltra-Massuet, I., & Arregi, K. (2005). Stress-by-structure in Spanish. Linguistic Inquiry, 36(1), 43–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotidis, P. (2014). Indices, domains and homophonous forms. Theoretical Linguistics, 40(3–4), 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotidis, P. (2018). (Grammatical) gender troubles and the gender of pronouns. In É. Mathieu, M. Dali, & G. Zareikar (Eds.), Gender and noun classification (pp. 186–200). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotidis, P. (2020). On the nature of roots: Content, form, identification. Evolutionary Linguistic Theory, 2(1), 56–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopapas, A., Tzakosta, M., Chalamandaris, A., & Tsiakoulis, P. (2012). IPLR: An online resource for Greek word-level and sublexical information. Language Resources and Evaluation, 46, 449–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punske, J., & Jackson, S. R. (2017). The bifurcated nature of plural: Reconsidering evidence from English compounds. In J. Nee, M. Cychosz, D. Hayes, T. Lau, & E. Remirez (Eds.), Proceedings of BLS 43 (pp. 261–283). Berkeley Linguistics Society. [Google Scholar]

- Ralli, A. (2000). A feature-based analysis of Greek nominal inflection. Glossologia, 11–12, 201–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ralli, A. (2002). The role of morphology in gender determination: Evidence from Modern Greek. Linguistics, 40(3), 519–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralli, A. (2006). On the role of allomorphy in inflectional morphology: Evidence from dialectal variation. In G. Sica (Ed.), Open problems in linguistics and lexicography (pp. 123–152). Polimetrica. [Google Scholar]

- Ralli, A. (2022). Μορφολογία [Morphology] (New revised edition). Patakis. [Google Scholar]

- Revithiadou, A. (1999). Headmost accent wins: Head dominance and ideal prosodic form in lexical accent systems (LOT Dissertation Series 15) [Ph.D. Thesis, HIL/Leiden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Revithiadou, A. (2007). Colored turbid accents and containment: A case study from lexical stress. In S. Blaho, P. Bye, & M. Krämer (Eds.), Freedom of analysis? (pp. 149–174) Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Revithiadou, A., & Lengeris, A. (2016). One or many? In search of the default stress in Greek. In J. Heinz, R. Goedemans, & H. van der Hulst (Eds.), Dimensions of phonological stress (pp. 263–290). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Revithiadou, A., & Markopoulos, G. (2021). A Gradient Harmonic Grammar account of nasals in extended phonological words. Catalan Journal of Linguistics, 20, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revithiadou, A., & Spyropoulos, V. (2016). Stress at the interface: Phases, accents and dominance. Linguistic Analysis, 4(1–2), 3–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, E. (2016). Predicting the unpredictable: Capturing the apparent semi-regularity of rendaku voicing in Japanese through harmonic grammar. In E. Clem, V. Dawson, A. Shen, A. H. Skilton, G. Bacon, A. Cheng, & E. H. Maier (Eds.), Proceedings of BLS 42 (pp. 235–249). Berkeley Linguistics Society. [Google Scholar]

- Scheer, T. (2016). Melody-free syntax and phonologically conditioned allomorphy. Morphology, 26, 341–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, D. (2010). Distributed Morphology. Language and Linguistics Compass, 4(7), 524–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, D. (2018). Distributed Morphology. In J. Audring, & F. Masini (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of morphological theory (pp. 143–165). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smolensky, P., & Goldrick, M. (2016). Gradient symbolic representations in grammar: The case of French liaison [Unpublished manuscript]. Microsoft Research AI and Johns Hopkins University & Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Starke, M. (2009). Nanosyntax: A short primer to a new approach to language. Nordlyd, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Svenonius, P. (2012). Spanning [Unpublished manuscript]. CASTL, University of Tromsø. [Google Scholar]

- Taraldsen Medová, L., & Wiland, B. (2019). Semelfactives are bigger than degree achievements: The nanosyntax of Czech and Polish semelfactive and degree achievement verb stems. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 37, 1463–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Thomadaki, E. (1994). Μορφολογικά προβλήματα της Νεοελληνικής: H κλίση του ουσιαστικού [Morphological problems in Modern Greek: Noun inflection] [Ph.D. Thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens]. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllidis, M. (2018). Νεοελληνική γραμματική (της Δημοτικής) [Modern Greek grammar (of the demotic variety)]. Institute of Modern Greek Studies. (Original work published 1941). [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, I. P. (1973). Modern Greek verb conjugation: Inflectional morphology in a transformational grammar. Lingua, 32, 193–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, E. (2018). Symbolic Representations in the Output: A case study from Moses Columbian Salishan stress. In S. Hucklebridge, & M. Nelson (Eds.), Proceedings of the forty-eighth annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society (NELS 48) (pp. 275–284). GLSA. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, E. (2021). Faded copies: Reduplication as distribution of activity. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 6(1), 58. [Google Scholar]

| Stem-Final Segment | Distribution | Allomorphy Pattern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grammatical Gender | Referent | Stress | ||

| /o/ | FEM/MASC/NEUT | ±human | U/PU/APU | -o/-Ø |

| /a/ | FEM/MASC | ±human | U/PU/APU | -a/-Ø |

| /i/ | FEM/MASC | ±human | U/PU/APU | -i/-Ø |

| Stem-Final Segment(s) | Distribution | Allomorphy Pattern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grammatical Gender | Referent | Stress | ||

| /a(ð)/ | MASC (mostly) | +human (mostly) | U (SG), PU (PL) | -á/-áð |

| /i(ð)/ | MASC | +human | PU (SG), APU (PL) | -i/-ið |

| /a(t)/ | NEUT | –human | APU | -a/-at |

| Structure/Feature | /o/, /a/, /i/ | /a(ð)/, /i(ð)/, /a(t)/ |

|---|---|---|

| Grammatical gender | any value | fixed value |

| Referent (±human) | any value | fixed value |

| Stress | any position | fixed position |

| Allomorphy pattern | V-Ø | V-VC |

| Theme Exponent | Database | APU | PU | U |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /o/ | ALex | 160 55.74% | 38 13.24% | 89 31.01% |

| TC | 79 43.16% | 25 13.66% | 79 43.16% | |

| /i/ | ALex | 4 1.6% | 180 72.28% | 65 26.1% |

| TC | 1 0.69% | 74 51.38% | 69 47.91% |

| Theme Exponent | APU | PU | U |

|---|---|---|---|

| /o/ | 144 45% | 78 24.37% | 98 30.62% |

| /i/ | 69 21.56% | 167 52.18% | 84 26.25% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markopoulos, G. Breaking Down Greek Nominal Stems: Theme and Nominalizer Exponents. Languages 2025, 10, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040085

Markopoulos G. Breaking Down Greek Nominal Stems: Theme and Nominalizer Exponents. Languages. 2025; 10(4):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040085

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkopoulos, Giorgos. 2025. "Breaking Down Greek Nominal Stems: Theme and Nominalizer Exponents" Languages 10, no. 4: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040085

APA StyleMarkopoulos, G. (2025). Breaking Down Greek Nominal Stems: Theme and Nominalizer Exponents. Languages, 10(4), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040085