“I Want to Be Born with That Pronunciation”: Metalinguistic Comments About K-Pop Idols’ Inner Circle Accents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Language Attitudes in Digital Spaces

2.2. English in South Korea

2.3. K-Pop Industry in Korea and Its Global Impact

2.4. Current Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Affect Toward Idols’ English Accents

4.2. Social Aspects Related to the Corresponding Affect

4.2.1. Social Attractiveness

| (1) | Korean original: | 젠틀섹시 조슈아…영어할 때 더 잘생겨짐 |

| English translation: | Gentle sexy Joshua...Becoming more handsome when speaking English |

| (2) | She doesn’t get every word exactly right, but her tone and pronunciation are the best I’ve ever heard from a non-native English speaker. Couple that with her kindness and intelligence, and Wendy really is an incredible idol and person. |

4.2.2. (Non-)Nativeness

| (3) | Even native Australia got shock hearing Felix’s thick Aussie accent |

| (4) | Rosé is a native English speaker but I’m still fascinated whenever she speaks English. I just melt whenever her voice become low |

| (5) | Jennie has the most neutral accent (unless she does her NZ accent) among all four... neither too ‘black’ not too ‘white’ nor too ‘Asian’ be it singing or speaking |

| (6) | I find Jennie’s kiwi accent to be very pretentious because she was only in New Zealand for 5 years and lived in Seoul for 19 to 18 years. She obviously knows how to speak English without the accent. Also I believe her accent isn’t truly kiwi anymore since she has live outside of the country for so long she would lose the authentic dialect. |

4.2.3. Off-Topic

| (7) | Korean original: | 한국은 이상한게 영어 잘 하면 무슨 엄청난 인텔리인 걸로 착각하는데 이런 풍조 좀 없어졌으면 좋겠다. 미국에서 오래 살았으니 영어 잘 하는거야 당연한거고, 미국 길바닥 거렁뱅이도 영어 잘 함. |

| English translation: | It’s strange that Korea mistakes for great intelligence when it comes to good English, but I hope this trend will disappear. Since he/she lived in the U.S. for a long time, he/she is good at English, of course. It’s natural, and homeless people in the US are also good at English. |

| (8) | Korean original: | 둘 다 영어 잘해서 개멋있다. 영어 잘하는 사람 ㅈㄴ 멋있어 |

| English translation: | Both of them are so cool because their English is so good, People who are good at English is fucking cool. |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agha, A. (2003). The social life of cultural value. Language & Communication, 23(3–4), 231–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, A. (2005). Voice, footing, enregisterment. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 15(1), 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H. (2014). Teachers’ attitudes towards Korean English in South Korea. World Englishes, 33(2), 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H., Choi, N., & Kiaer, J. (2020). South Korean perceptions of “native” speaker of English in social and news media via big data analytics. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 9(1), 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.-Y., & Kang, H.-S. (2017). South Korean university students’ perceptions of different English varieties and their contribution to the learning of English as a foreign language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(8), 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulos, J. (2015). Networked multilingualism: Some language practices on Facebook and their implications. International Journal of Bilingualism, 19(2), 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, E., & Vásquez, C. (2018). ‘Cash me ousside’: A citizen sociolinguistic analysis of online metalinguistic commentary. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 22(4), 406–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S. (2003). Foreign-born teachers in the multilingual classroom in Sweden: The role of attitudes to foreign accent. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 6(3–4), 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, E. M., & Brennan, J. S. (1981). Accent scaling and language attitudes: Reactions to Mexican American English speech. Language and Speech, 24(3), 207–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Y. G. (2007). How are nonnative-English-speaking teachers perceived by young learners? TESOL Quarterly, 41(4), 731–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J. H. (2016). Korean EFL college learners’ perspectives toward World Englishes. Journal of the Korean English Education Society, 15(4), 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-A. J., & Herring, S. C. (2024). “What a standard Taiwan Mandarin accent”: Online metalinguistic commentary on linguistic performances of non-native Chinese speakers. Language & Communication, 99, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, E. W. (2017). How to drop a name: Hybridity, purity, and the K-pop fan. Language in Society, 46(1), 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, C. (2016). “Ets jast ma booooooooooooo”: Social meanings of Scottish accents on YouTube. In L. Squires (Ed.), English in computer-mediated communication: Variation, representation, and change (pp. 69–98). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, C. (2020). Metapragmatic comments and orthographic performances of a New York accent on YouTube. World Englishes, 39(1), 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, T. (2003). What do ESL students say about their accents? The Canadian Modern Language Review, 59(4), 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiza, D. (2020). Stimulating English learning in global K-pop community on Twitter. Journal of Applied Linguistics (ALTICS), 2(1), 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, J. N., Gottdiener, W. H., Martin, H., Gilbert, T. C., & Giles, H. (2012). A meta-analysis of the effects of speakers’ accents on interpersonal evaluations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondelaers, S., van Hout, R., & van Gent, P. (2019). Re-evaluating the prestige of regional accents in Netherlandic Standard Dutch: The role of accent strength and speaker gender. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 38(2), 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, B., van Meurs, F., & Reimer, A.-K. (2018). The evaluation of lecturers’ nonnative-accented English: Dutch and German students’ evaluations of different degrees of Dutch-accented and German-accented English of lecturers in higher education. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 34, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, B., van Meurs, F., & Usmany, N. (2023). The effects of lecturers’ non-native accent strength in English on intelligibility and attitudinal evaluations by native and non-native English students. Language Teaching Research, 27(6), 1378–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyd, T. (2016). Global varieties of English gone digital: Orthographic and semantic variation in digital Nigerian Pidgin. In L. Squires (Ed.), English in computer-mediated communication: Variation, representation, and change (pp. 101–122). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IFPI. (2021). Global music report 2021. Available online: https://www.ifpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GMR2021_STATE_OF_THE_INDUSTRY.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Jaworski, A., Coupland, N., & Galasiński, D. (2004). Metalanguage: Why now? In A. Jaworski, N. Coupland, & D. Galasiński (Eds.), Metalanguage: Social and ideological perspectives (pp. 3–8). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D. Y. (2021). The BTS sphere: Adorable Representative M.C. for Youth’s transnational cyber-nationalism on social media. Communication and the Public, 6(1–4), 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D. Y. (2024). The rise of digital platforms as a soft power apparatus in the New Korean Wave era. Communication and the Public, 9(2), 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. (2014). Youth, social media and transnational cultural distribution: The case of online K-pop circulation. In A. Bennett, & B. Robards (Eds.), Mediated youth cultures (pp. 114–129). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B. B. (1992). World Englishes: Approaches, issues and resources. Language Teaching, 25(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. (2023). The politics of being a K-pop fan: Korean fandom and the ‘cancel the Japan tour’ protest. International Journal of Communication, 17, 1019–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, O. (2015). Learners’ perceptions toward pronunciation instruction in three circles of World Englishes. TESOL Journal, 6(1), 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, O., & Rubin, D. L. (2009). Reverse linguistic stereotyping: Measuring the effect of listener expectations on speech evaluation. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 28(4), 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, O., & Yaw, K. (2021). Social judgment of L2 accented speech stereotyping and its influential factors. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(4), 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y. (2012). Singlish or Globish: Multiple language ideologies and global identities among Korean educational migrants in Singapore. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 16(2), 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Customs Service. (2023). Recited from Chosun Ilbo, “after PSY and BTS, there is no “mega-hit” songs that the world sings along to” February 25, 2023. 싸이·BTS 이후… 세계가 따라부르는 ‘대형 히트곡’이 없다. Available online: https://www.chosun.com/culture-life/culture_general/2023/02/25/D3WNFJHXR5BDPEYMZOHQDS6YBE/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Kutlu, E. (2023). Now you see me, now you mishear me: Raciolinguistic accounts of speech perception in different English varieties. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 44(6), 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (2006). The social stratification of English in New York city. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, W. E. (1967). A social psychology of bilingualism. Journal of Social Issues, 23(2), 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, W. E., Hodgson, R. C., Gardner, R. C., & Fillenbaum, S. (1960). Evaluational reactions to spoken languages. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 60(1), 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. S. (2014). English on Korean television. World Englishes, 33(1), 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, S., Campbell, M.-A., Litzenberg, J., & Subtirelu, N. C. (2016). Explicit and implicit training methods for improving native English speakers’ comprehension of nonnative speech. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, 2(1), 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z., & Haider, S. (2023). Online community development through social interaction—K-pop stan twitter as a community of practice. Interactive Learning Environment, 31(2), 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, U., & Appiah, O. (2016). Perspective taking to improve attitudes towards international teaching assistants: The role of national identification and prior attitudes. Communication Education, 65(2), 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C., & McRae, S. (2010). A pre-trial collection and investigation of what perceptions and attitudes of Konglish exist amongst foreign and Korean English language teachers in terms of English education in Korea. Asian EFL, 12, 134–164. [Google Scholar]

- Min, B.-S. (2024). The K-pop industry: Competitiveness and sustainability. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M. (2014). New York city English. Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Octaviani, A. D., & Yamin, H. M. A. (2020). The rise of English among K-pop Idols: Language aarieties in the immigration. In International university symposium on humanities and arts (INUSHARTS 2019) (pp. 117–121). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pantos, A. J., & Perkins, A. W. (2012). Measuring implicit and explicit attitudes toward foreign accented speech. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 32(1), 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D. (1992). Nonlanguage factors affecting undergraduates’ judgments of nonnative English-speaking teaching assistants. Research in Higher Education, 33(4), 511–531. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. (1998). Help! My professor (or doctor or boss) doesn’t talk English! In J. N. Martin, T. K. Makayama, & L. A. Flores (Eds.), Readings in cultural contexts (pp. 149–160). Mayfield. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. (2012, September 16–17). The power of prejudice in accent perception: Reverse linguistic stereotyping and its impact on listener judgments and decisions [Paper presentation]. 3rd Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference (pp. 11–17), Ames, IA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D., Coles, V. B., & Barnett, J. T. (2016). Linguistic stereotyping in older adults’ perceptions of health care aides. Health Communication, 31(7), 911–916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ryan, E. B., Carranza, M. A., & Moffie, R. W. (1977). Reactions toward varying degrees of accentedness in the speech of Spanish-English bilinguals. Language and Speech, 20(3), 191–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymes, B., & Leone-Pizzighella, A. (2018). YouTube-based accent challenge narratives: Web 2.0 as a context for studying the social value of accent. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2018(250), 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J., & Mallette, L. A. (2017). Environmental coding: A new method using the SPELIT environmental analysis matrix. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(2), 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K. (2019). Korean elementary pre-service teachers’ experience of learning and using English and attitudes towards World Englishes. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 16(1), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, C. J., & Hopper, R. (1985). Measuring language attitudes: The speech evaluation instrument. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 4(2), 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Account | The Number of Subscribers | The Title of the Video | Released Date | The Number of Views | The Number of Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Doyouram-Everyday K-Culture | 21.6 M (million) | 알고 들으면 더 신기한 아이돌 영어발음 특징 (RM, JOSHUA, ROSÉ, JENNIE, WENDY, MARK) [ENG] [Idol English pronunciation characteristics that is more surprising if you know it (RM, JOSHUA, ROSÉ, JENNIE, WENDY, MARK) [ENG]] | 16 August 2021 | 203,435 | 431 |

| 2 | JTBC Voyage | 349 M | ♨핫클립♨ 거침없는 영어실력 뽐낸 레드벨벳 웬디 (Red Velvet WENDY) (발음도 이뻐♥) #스테이지K #JTBC봐야지 [♨ Hot Clip♨ Red Velvet WENDY who boasted her fluent English skills (Pronunciation is pretty♥) #StageK #JTBC] | 7 April 2019 | 4,143,521 | 1815 |

| 3 | 영크릿 | Young Cret | 20.9 M | [BLACK PINK]블랙핑크 제니 영어 뉴질랜드 발음 VS 로제 호주발음 비교해보자 (영어공부|ENG SUB) [[BLACK PINK] Let’s compare BLACKPINK Jennie’s English New Zealand pronunciation vs Rosé’s Australian pronunciation. (English study|ENG SUB)] | 6 July 2020 | 1,887,408 | 1232 |

| 4 | [BLACKPINK, STRAY KIDS] 블랙핑크 로제 영어 VS 스트레이키즈 필릭스 영어 원어민 실화냐? (영어공부|ENG SUB) [[BLACKPINK, STRAY KIDS] BLACKPINK Rose English VS Stray Kids FELIX English native speaker, is it real? (English study|ENG SUB)] | 18 July 2020 | 699,728 | 1106 |

| No. | Idols’ Names | Gender | Demographic Background | Accents Described in the Video |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joshua | Male | Born and raised in the US. | Valley girl accent |

| 2 | Mark | Male | Born and raised in Canada | New York accent |

| 3 | Wendy | Female | Born in Korea, moved to Canada when she was 11 years old. | American accent |

| 4 | Rosé | Female | Born in New Zealand, moved to Australia when she was 7 years old. | Australian accent |

| 5 | Jennie | Female | Born in Korea, studied abroad in New Zealand when she was 9 years old and stayed there for five years | New Zealand accent |

| 6 | RM | Male | Born and raised in Korea | Undefined |

| 7 | Felix | Male | Born and raised in Australia | Australian accent |

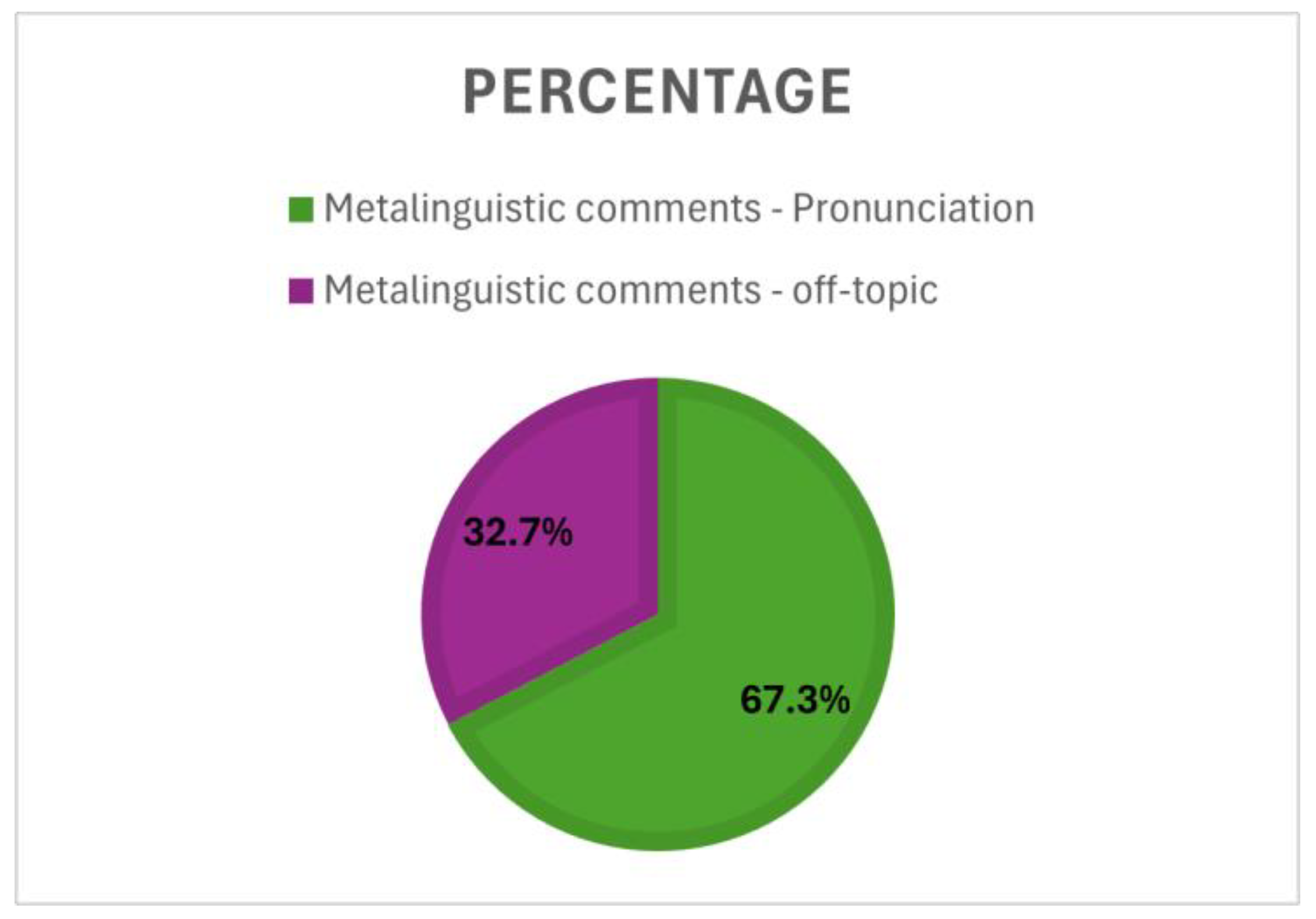

| Metalinguistic Comments (n = 602) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Languages of the Comments | English | Korean |

| Examples | Data ROSIE’s accent is so ELEGANT and MAGESTIC. its chef’s kiss | “남준 오빠 영어 발음 개섹시해 ㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠ T: Namjoon’s English pronunciation is so sexy” |

| Video#1 | 82 | 53 |

| Video#2 | 109 | 10 |

| Video#3 | 143 | 31 |

| Video#4 | 110 | 64 |

| Tally | 444 (74.1 %) | 158 (25.9 %) |

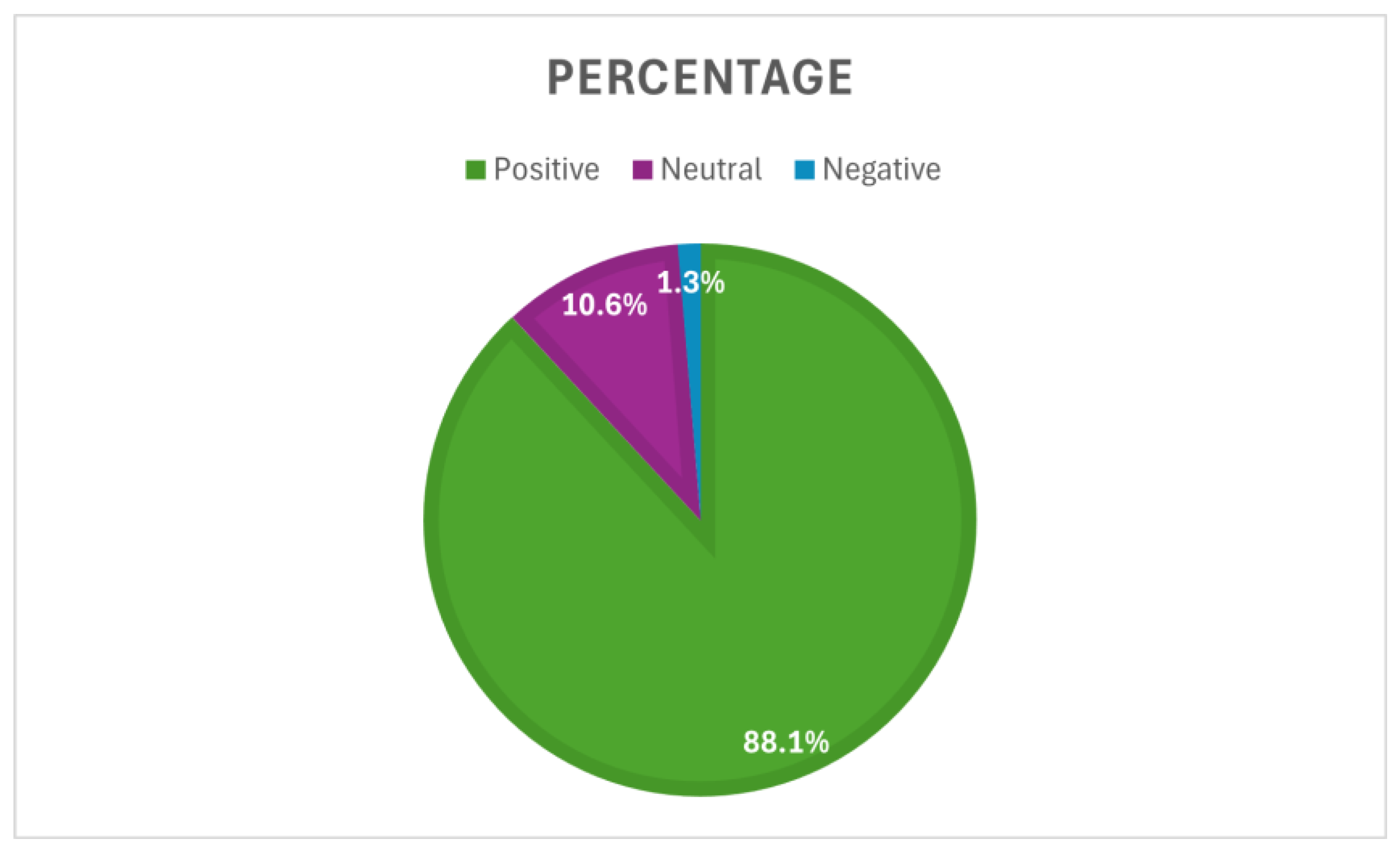

| General Evaluation | Percentage (Number) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | 88.1% (357) | Overall positive evaluation (e.g., I want to be born with that pronunciation), Adjectives of positive evaluation (e.g., Rose and her aussie accent is so elegant) |

| Neutral | 10.6% (43) | Mere description of accent (e.g., They both speak aussie accent) |

| Negative | 1.3% (5) | Adjectives of negative evaluation (e.g., I find Jennie’s kiwi accent to be very pretentious) |

| Aspect | Examples | %(n) * |

|---|---|---|

| Social attractiveness | 젠틀섹시 조슈아... 영어할 때 더 잘생겨짐 (T: Gentle sexy Joshua...Becoming more handsome when speaking English) | 33.6% (136) |

| (Non)-nativeness | Even native Australia got shock hearing Felix’s think Aussie accent | 30.3% (123) |

| Phonetic features | Rose’s voice is very soothing and smooth (coming from an Australian, I don’t really understand why people love our accent because to us it sounds not that unique haha). It’s also interesting to see Rose’s accent sometimes switches to a more American pronunciation eg) rolling r sound in some words over time. Maybe from being with Jannie for so long with her half kiwi half American accent | 4.7% (19) |

| Speech | I am very impressed with Rose, and not because of her accent or how fluent she is or how she pronounces the words. I am impressed because of what comes out of her mouth. They are not only instantaneous responses, but very intelligent as well. She doesn’t just open her mouth to speak, they are all carefully selected and well thought, and she does it in split second. | 3.7% (15) |

| Motivation | I watched the video because of their accent but finished it with so much inspiration that I too can achieve my dreams if I work hard for it. | 3.2% (13) |

| Proficiency | I love Wendy’s accent, like she’s so fluent in English. not like me though I’m not good at English and I’m not that so fluent and accent at it... | 2.2% (9) |

| Comprehensibility | Jennie’s English is so soothing to hear. The words are so clear, like we don’t need subtitles to understand her. | 2.2% (9) |

| Metalinguistic | Many people can relate with rose, so do I. we will show our different character based on the language we speak. I love | 0.7% (3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Zhang, L. “I Want to Be Born with That Pronunciation”: Metalinguistic Comments About K-Pop Idols’ Inner Circle Accents. Languages 2025, 10, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040075

Kim J, Zhang L. “I Want to Be Born with That Pronunciation”: Metalinguistic Comments About K-Pop Idols’ Inner Circle Accents. Languages. 2025; 10(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jihye, and Luoxiangyu Zhang. 2025. "“I Want to Be Born with That Pronunciation”: Metalinguistic Comments About K-Pop Idols’ Inner Circle Accents" Languages 10, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040075

APA StyleKim, J., & Zhang, L. (2025). “I Want to Be Born with That Pronunciation”: Metalinguistic Comments About K-Pop Idols’ Inner Circle Accents. Languages, 10(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040075