1. Introduction

This paper explores the dynamic interplay and complex relationship between the universal and the particular by examining one of the defining characteristics of human language, namely its ability to display long-distance filler–gap dependencies (cf.

Sprouse et al., 2016), as (1) illustrates for English:

Who did Peter see __ yesterday?

Who do you think [that Peter saw __ yesterday]?

Who do you think [that she believes [that I said [that Peter saw __ yesterday]]]?

The examples in (1) involve question formation with varying degrees of dependency length between the

filler (i.e.,

who) and the

gap (i.e., the underlined spaces). The filler in a sense leads a ‘double life’ being spelt out at one location (the sentence-initial position) and interpreted in another (in the object position). In (1a), the filler–gap dependency is contained within a main clause, while it crosses a clausal boundary (indicated by square brackets) in (1b). The bidirectional association between the fronted element and its gap has been argued to be unbounded in principle, i.e., theoretically speaking, there should be no limit to the possible distance between the two. In (1c), the fronted element,

who, moves across no less than three clausal boundaries on its way to its final landing site at the front of the sentence. Certain structures with long-distance dependencies, however, appear to indeed be ‘bounded’, in the sense that L1 users (native speakers) tend to find them unacceptable. More specifically, problems appear to arise in specific structural environments, which

Ross (

1967) metaphorically dubbed

islands, because they are difficult or impossible to escape from (referencing the story of Robinson Crusoe); in order to appreciate the motivation behind the present L2 study on this type of structure, an understanding of recent developments within L1 island research is necessary.

In the tradition of generative grammar and in modern theorizing (e.g.,

Bošković, 2015;

Chomsky, 2001;

Nunes & Uriagereka, 2000;

Phillips, 2013a,

2013b;

Sabel, 2002;

Villata et al., 2016), extraction from island structures are assumed to be ungrammatical due to a violation of universal syntactic. Among the configurations thought to be island structures are embedded questions, as in (2a), adverbial (or adjunct) clauses

1 (2b), and relative clauses (2c). As a result, extraction from such clauses may lead to ungrammaticality (signaled by ‘*’):

The proposed constraints on filler–gap dependencies were originally based on English (

Ross, 1967;

Chomsky, 1964;

Huang, 1982), but they have traditionally been assumed to be universal. As a result, island effects have been a major part of theory-building in generative syntax, being used as a diagnostic for binding and movement in numerous analyses. Yet, even though island configurations are thought to be ungrammatical in the tradition of generative grammar, there appears to be a lot of variation both across speakers and across languages, so the purported universal constraints have continuously faced counterevidence. The Mainland Scandinavian languages have provided fascinating data points, since they exhibit consistent exceptions and have hence been argued to be more permissible when it comes to the space of possibilities for filler–gap dependencies, as sentences of the types in (2) have frequently been attested in naturally occurring speech (

Engdahl & Ejerhed, 1982;

Lindahl, 2017). Observe the following examples in (3) from the syntax literature:

- b.

those flowers know I a man who sells

‘I know a man who sells those flowers’

- c.

Hvilken film var det du gärna ville veta

which movie was it you please would know

who that had directed

‘Which movie would you like to know who had directed?’

The example in (3a) from Danish violates the Condition on Extraction Domain (CED,

Huang, 1982), which basically states that extraction can only take place from a complement clause, cf. (1b–c); the Swedish one in (3b) violates the Complex NP Constraint (

Ross, 1967), and (3c) is a Swedish counterexample to the proposed ban on extraction from an embedded question, i.e., a

wh-island (

Chomsky, 1964). Examples like these have compelled some syntacticians to argue that the counterexamples are not really counterevidence, and that their underlying structures are different from their apparent surface structure (e.g.,

Chomsky, 1982;

Kush & Lindahl, 2011;

Phillips, 2013a,

2013b). However, in a series of psycho- and neurolinguistic experiments, we have found that certain island structures indeed appear to be grammatical in Danish: Though the actual level of acceptability varies a lot, from well below to well above the middle range, other factors suggest that they are indeed grammatical. First, the acceptability of extraction from relative clauses is positively correlated with the frequency of the matrix verb (a lexical effect). Second, extraction from embedded questions and from relative clauses becomes more acceptable with increased repeated exposure (trial or satiation). Third, extraction from adjunct clauses depends on the complementizer. Finally, actual examples of all of these island violations are easy to find (

K. R. Christensen et al., 2013a,

2013b;

K. R. Christensen & Nyvad, 2014,

2024;

Nyvad et al., 2017;

Nyvad & Christensen, 2023). In English, on the other hand, the ratings for extraction from relative clauses and embedded questions did not increase as a function of repeated exposure or lexical frequency of the matrix verb (

K. R. Christensen & Nyvad, 2019,

2022). For relative clauses, the ratings did not differ significantly from unambiguously ungrammatical controls.

Furthermore, in a recent study on English (

Nyvad et al., 2022), we made the remarkable discovery that English appears to be quite permissive towards extraction by relativization from a range of adjunct clause types (see also

Sprouse et al., 2016, who found island effects for

wh-movement but not for relativization from

if-clauses in English). This pattern is echoed in a corpus study which has found a range of examples in English of the island type in (4) (

Müller & Eggers, 2022, p. 11):

(4) Many of the exercises are ones [that I would be surprised [if even 1 percent of healthy women can do __]] (Corpus of Contemporary American English 2008).

Findings such as these suggest that island constraints may not be universal and that long-distance filler–gap dependencies into certain island environments may in fact be grammatical, under the right discourse conditions and if the right comparisons are made.

Given these developments in island research, another important question emerges, namely whether crosslinguistic differences in island sensitivity can be attested in transfer from L1 to L2, which is a central question in second language acquisition research. The

Full Transfer Full Access hypothesis (

Schwartz & Sprouse, 1994,

1996;

White, 1985,

2003, p. 66 ff) states that the early phases of second language learning are based on the L1 grammar (hence, ‘Full Transfer’)

2 and that the learner has ‘Full Access’ to the syntactic constraints of so-called Universal Grammar that constrain the space of possibility in the interlanguage (i.e., in the development stages from L1 to L2). For instance, it has been found that L1 speakers of languages without overt

wh-movement, such as Chinese and Indonesian, reject the same violations of certain island constraints as L1 English users, both in their L1 and in their L2 English (

Martohardjono, 1993; see the discussion in

Slabakova, 2021, pp. 225–226; see also

Huang, 1982,

2009). This result indicates that the learner has ‘Full Access’ to the parts of Universal Grammar that are responsible for constraining extraction from islands, e.g., in the form of the CED mentioned above. In addition, there might be parametric options with respect to abstract functional structure, allowing or disallowing extraction from certain island environments, as suggested by research carried out by

Kush and Dahl (

2020) and

Kush et al. (

2023), who found that island insensitivity with respect to extraction from embedded questions in Norwegian L1 was transferred into English L2.

Previous research suggests that Danes transfer (part of) their grammar into L2 English, judging extraction from relative clauses higher than speakers of L1 English (

Nyvad & Christensen, 2023). The purpose of the current study is to investigate whether judgements of island structures in an L2 language mirror those of L1 users of the target language (here, Danish), or the participants’ L1 (here, English). In other words, do L1 English users learning Danish as a foreign language judge island structures in Danish as more acceptable than L1 Danish users (indicating transfer from English) or as less acceptable (in which case, transfer is not indicated)? The object of study here is relativization out of adverbial clauses, which, in one recent series of experiments (

Nyvad et al., 2022,

2024;

Nyvad & Christensen, 2023), has been found—quite unexpectedly—to be more acceptable in English than in Danish: In English, there was no significant difference between extraction from

if-clauses (adjuncts) and

that-clauses (complements), while extraction from

when-clauses was rated lower, and extraction from

because-clauses even lower ({

that,

if} >

when >

because). In Danish, on the other hand, extraction from

if-clauses was significantly less acceptable than extraction from

that-clauses, and while extraction from

when and

because was even less acceptable, there was no difference between the two (

that >

if > {

when,

because}). Furthermore, whereas the acceptability profiles of extraction from

if-, when-, and

because-clauses seemed to suggest that none of them were strong islands in English (they did not exhibit large island effects

3), all three did show large island effects in Danish (in terms of DD scores, see

Section 3.2 below).

This contrast in effect sizes found in English and Danish in this comparative study (see

Nyvad & Christensen, 2023) suggests that the constraints on island configuration are subject to a parametric setting (e.g., in the form of an extra layer of functional structure, see

Nyvad et al., 2022), and the existence of the crosslinguistic difference attested here opens up the possibility that the parameter on which the variation hinges can be transferred from L1 to L2 (see also

Kush et al., 2023). Given a seeming lack of positive evidence for a conflict between English L1 and Danish L2 grammars, a more conservative resetting of the L2 grammar is unlikely. That is, since there is no overt indication in the input that extraction from adverbial clauses should be blocked, L1 English users have no reason to restrict the grammar in their L2 Danish. Hence, based on the

Full Transfer Full Access hypothesis, we predicted the following:

Prediction 1: L1 English users judge extraction from adverbial clauses in L2 Danish to be on the same acceptability level as in L1 English.

Prediction 2: Acceptability of extraction from adverbial clauses is not correlated with level of proficiency in Danish.

If UG disallows extraction from adjunct clauses (

Stepanov, 2007; see also

Bode, 2020), we would not expect transfer of lenience from L1 to L2. Moreover, it is still unclear whether the restrictions on extraction from island configuration are gradient or, as predicted here, categorical in nature. This study may thus help elucidate a more general question about the nature of island constraints.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on previous studies on English and Danish carried out in our research group, we conducted an L2 acceptability judgment experiment in the form of a questionnaire in Google Form, disseminated on social media platforms and through other social networks. We wanted to test whether extraction from three different types of adjunct clauses in Danish (corresponding to

if-,

when-, and

because-clauses in English) would be as (un)acceptable to L1 English users in L2 Danish as they are to L1 Danish users. The test sentences were translated versions of the English stimulus set in

Nyvad et al. (

2022), albeit modified slightly in a few cases where direct translation was not possible. Minimally contrasted example sentences, modelled on the naturally occurring data in the text corpora and manipulated according to factors theorized to be of importance to acceptability level (e.g., complementizer type, extraction, semantic and pragmatic coherence, lexical frequency), were divided onto eight carefully balanced lists using a Latin square design. They were randomly mixed with filler-sentences (corresponding examples with subject islands and coordinate structures), and participants judged their acceptability using a Likert scale from 1 (“unacceptable”) to 7 (“acceptable”). Below is an example of a stimulus set (examples of filler sentences can be found in

Appendix A). Each target stimulus sentence was preceded by a short facilitating context. We carefully constructed the materials such that the same context could be used to precede all eight types, as shown in (6). (The entire stimulus set is available online, see the Data Availability Statement.)

(6) TARGET. CONTEXT:

I det sidste træningsprogram jeg udarbejdede for Emma, ville jeg gøre det så godt som umuligt for hende og inkluderede derfor endnu et sæt virkelig brutale pull-ups.

‘In the latest workout routine I designed for Emma, I really wanted to make it impossible for her and included another set of particularly brutal pull-ups.’

NON-ISLAND STRUCTURE [-EXTRACTION]:

Det er åbenlyst at jeg blev overrasket over

It is obvious that I became surprised over

at hun faktisk gennemførte dét program.

that she actually completed that exercise

‘It’s obvious that I was surprised that she actually completed this exercise.’

ISLAND STRUCTURE [-EXTRACTION]:

- b.

Det er åbenlyst at jeg ville blive overrasket

It is obvious that I would be surprised

hvis hun faktisk gennemførte dét program.

if she actually completed that exercise

‘It’s obvious that I would be surprised if she actually completed this exercise.’

- c.

Det er åbenlyst at jeg blev overrasket da hun faktisk gennemførte dét program.

It is obvious that I was surprised when she actually completed that exercise.

- d.

Det er åbenlyst at jeg blev overrasket fordi hun faktisk gennemførte dét program.

It is obvious that I was surprised because she actually completed that exercise.

NON-ISLAND STRUCTURE [+EXTRACTION]:

- e.

Det er er dét program som jeg blev overrasket over

It is that exercise that I became surprised over

at hun faktisk gennemførte.

that she actually completed

‘This is the exercise that I was surprised that she actually completed.’

ISLAND STRUCTURE [+EXTRACTION]:

- f.

Det er er dét program som jeg ville blive overrasket

It is that exercise that I would be surprised

hvis hun faktisk gennemførte.

ifshe actually completed

‘This is the exercise that I would be surprised if she actually completed.’

- g.

Det er er dét program som jeg blev overrasket da hun faktisk gennemførte.

‘This is the exercise that I was surprised when she actually completed.’

- h.

Det er dét program som jeg blev overrasket fordi hun faktisk gennemførte.

‘This is the exercise that I was surprised because she actually completed.’

We chose to use extraction by relativization in the experiment in order to provide optimal conditions for extraction for two reasons: One, because

wh-dependencies in questions have been found to potentially affect the acceptability of extraction from island environments negatively (

Sprouse et al., 2016). Two, because we wanted to be able to compare the acceptability judgements of our English speakers of L2 Danish as directly as possible to previous studies which tested relativization (

Nyvad et al., 2022,

2024;

Nyvad & Christensen, 2023).

This design gave us eight target types (see

Table 1), which we used as the levels for a type factor for our statistical model in order to test for interactions between extraction and the four clause types. This design also follows the logic of the 2 × 2 design (±Island x ±Extraction) from

Sprouse et al. (

2012).

Participants were asked to rate their own level of proficiency in L2 Danish (“How would you rate your own level of proficiency in Danish?”) on a 10-point Likert scale (0 = “beginner”, 10 = “(near-) native”). We did not ask for further information about their place of residence, age at onset of learning, etc. Though this subjective and very simple self-reported L2 proficiency is obviously only a proxy for a more elaborate, objective proficiency measure, previous research has shown significant positive correlations between self-reported language measures and actual linguistic ability (

Marian et al., 2007;

Kaushanskaya et al., 2020;

Macbeth et al., 2022; but see

Tomoschuk et al., 2019).

A total of 40 L1 English users with Danish as L2 participated in the experiment. One self-reported to have a proficiency in Danish of 0 and judged everything, including clearly ungrammatical coordinate structure violations (filler 2), to be more or less equally acceptable, and was therefore excluded from the analysis. Consequently, the number of participants included in the analysis was 39 (23 female, 15 male, 1 other; aged 18–66 years, mean = 39.2, SD = 14.4). The mean proficiency in Danish was 8.0 (range 2–10, SD = 2.1). The number of participants on lists 1–8 of the Latin square design was 6, 2, 6, 6, 4, 4, 4, and 7, respectively.

4 4. Discussion

We had two main predictions in this L2 study, the first of which was that L1 English users judge extraction from adverbial clauses in L2 Danish to be on the same acceptability level as in L1 English (

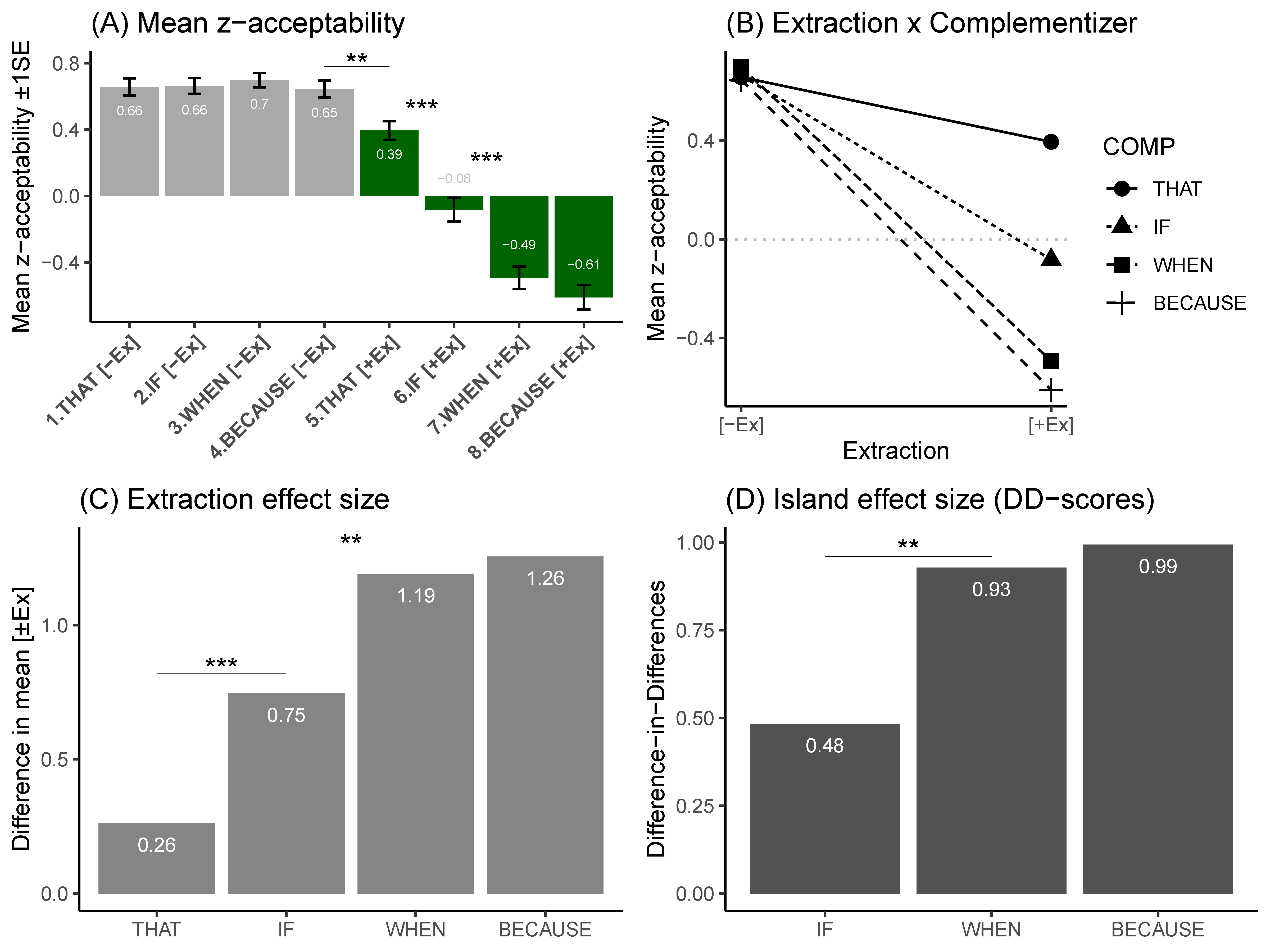

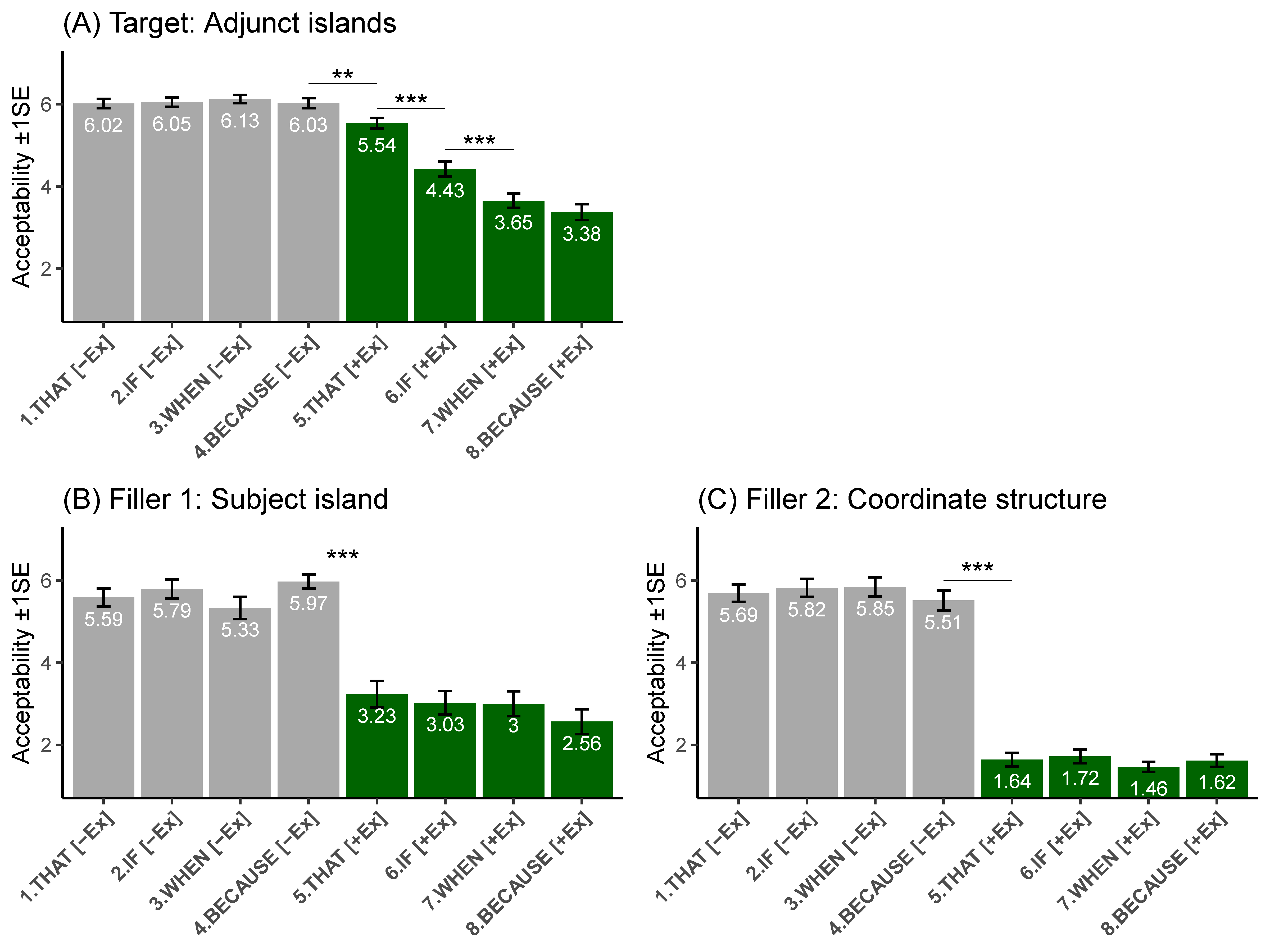

Nyvad et al., 2022) due to transfer. In other words, these L1 English users should not perceive adverbial clauses as strong islands in L2 Danish. As regards the DD scores in

Figure 2D, this assumption turned out to only hold true with respect to extraction from

if-clauses, with a difference-in-difference score well below the 0.75 threshold of

Kush et al. (

2018,

2019) for islandhood, while extraction from both

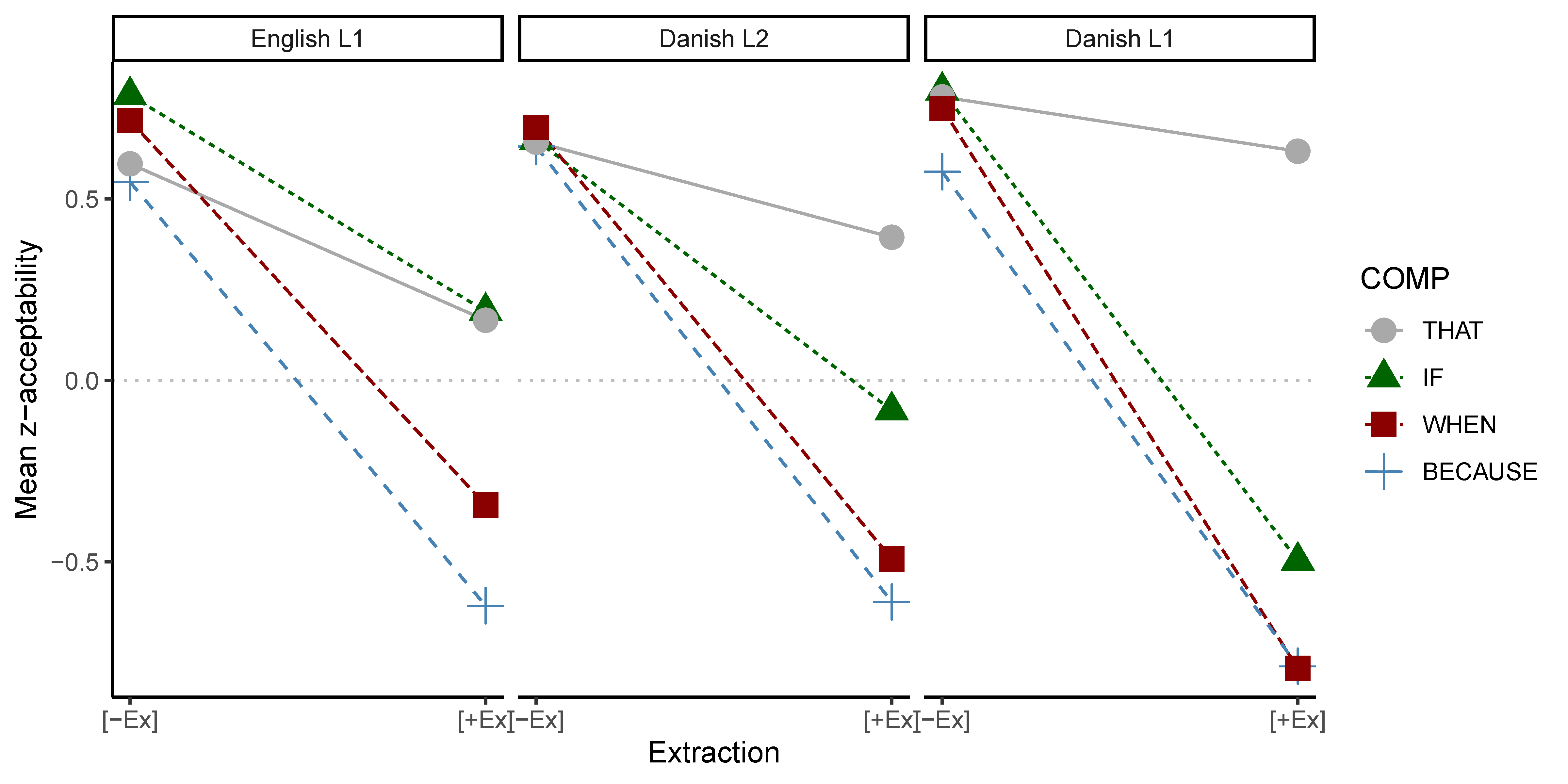

when- and

because-clauses exceeded it. However, the island effect of extracting from adjunct clauses appears to be smaller for L1 English users (in their L1 as well as L2 Danish) across the three different adverbial clause types than what was found for the corresponding constructions in L1 Danish. The results of our experiments suggest that our participants have transferred a more permissive stance towards relativization out of adverbial clauses from their English L1 into their Danish L2, thus at least partially confirming Prediction 1.

Our results showed variation and gradience in the acceptability of extraction from adjunct clauses, such that extraction across

if was more acceptable than across

when, which was more acceptable than

because.

6 This gradient pattern is not easily accounted for with a single (potentially transferrable) parameter that categorically enables or blocks extraction. This kind of gradience is more readily compatible with discourse-functional approaches to island structures (

Erteschik-Shir, 1982;

Deane, 1991;

Kuno, 1987;

Goldberg, 2005;

Abeillé et al., 2020), which have tried to explain systematic crosslinguistic variation with reference to how a particular language codes information structure. In the case of island configurations, they typically focus on the special discourse status of the configurations: The filler–gap dependency involves fronting, which arguably also has to be licensed by pragmatics. The unacceptability of island constructions can thus be seen as a reflection of infelicity (at least in part) due to, e.g., the topic/focus status of the extraction domain and/or the filler. This opens the possibility of gradience, but, generally speaking, these accounts have not explicitly operationalized core concepts that they argue give rise to the fine-grained differences in acceptability that we see across constructions and across languages (e.g., testable levels of strength of focus and topic or gradience in backgroundedness, presupposition, veridicality, etc., see

Nyvad et al., 2022). On the other hand, the fact that we found variation between the three different adverbial clause types in this L2 study appears to be an independent issue, given that the contrasts are robust across languages and across L1 and L2:

if-clauses are consistently judged as having higher acceptability than

when- and

because-clauses, and

because-clauses systematically receive the lowest ratings. The variation between the adjunct clause types is discussed at length by

Nyvad et al. (

2022, pp. 16–22), who point to differences in, e.g., attachment height, functional structure, feature-based intervention effects, semantic coherence, and discourse function as potential factors.

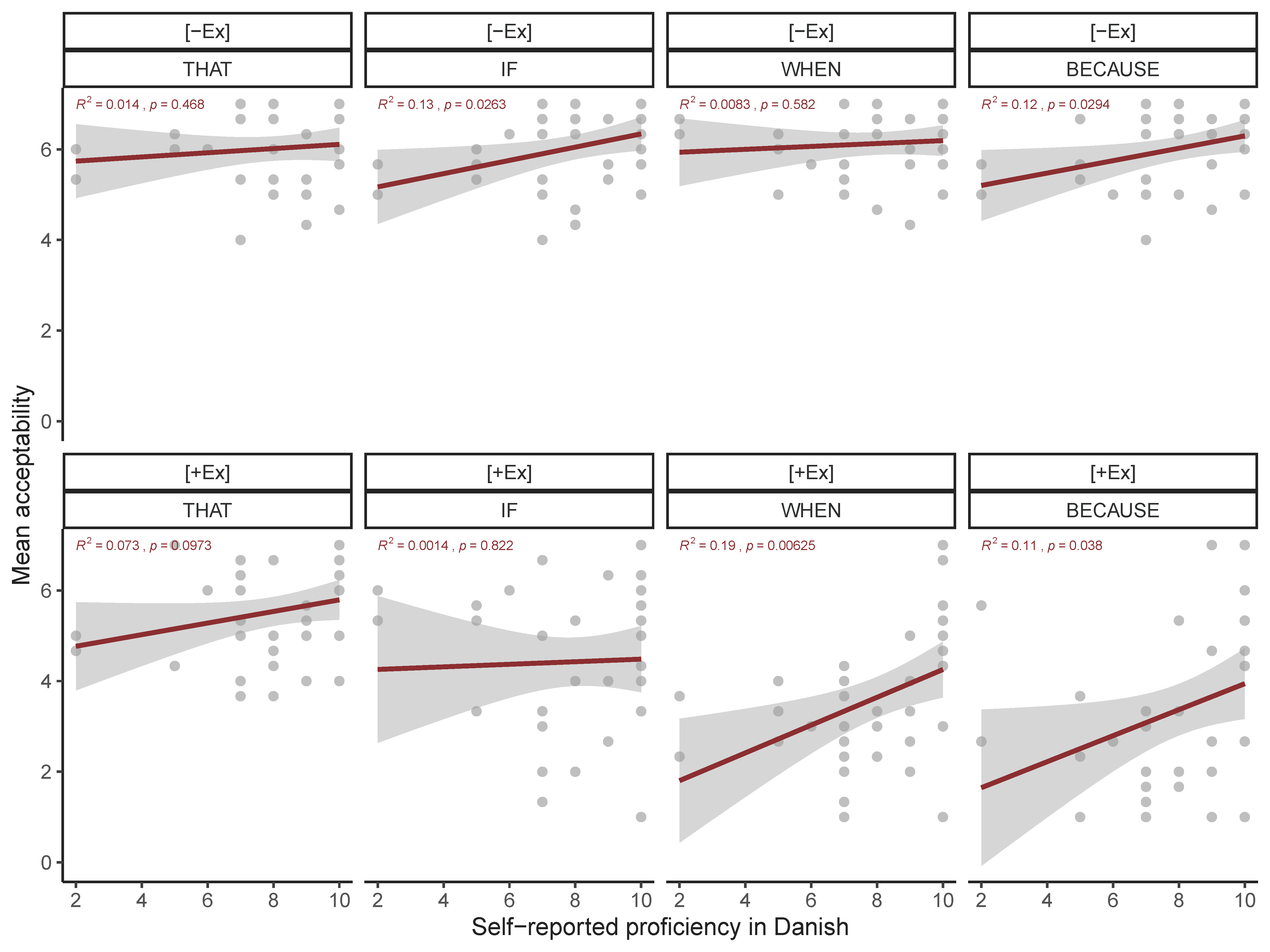

Our second prediction was that the acceptability level of extraction out of adverbial clauses would not be correlated with level of proficiency in Danish, i.e., the more proficient in Danish an L1 English user becomes, the more they perform like L1 Danish users when processing Danish sentences. However, surprisingly, we found that an increase in the self-reported level of proficiency in L2 Danish is correlated with an increase in perceived acceptability of island extractions.

One explanation for this pattern may be that the L1 English users who have reached a high level of proficiency in L2 Danish have constructed a Danish grammar that is more tolerant towards long-distance extraction

in general than their L1 English is. This overall discrepancy between Danish and English when it comes to island extractability has been attested multiple times in the syntax literature (for example,

Nyvad et al., 2017;

Vikner et al., 2017), and has been ascribed in part to the propensity to front elements via topicalization in the Mainland Scandinavian languages (

Engdahl, 1997). The mixed picture that emerges from our results may be due to this complex interplay between the particular construction under investigation (i.e., relativization from adverbial clauses), which appears to be surprisingly low in acceptability in Danish, and general tendencies in the two languages when it comes to long-distance extraction, where relative clauses and embedded questions appear to be strong islands in English, but not in Danish (REFS). Maybe the participants (consciously or subconsciously) let their awareness that Danish is more lenient toward extraction in general interfere with their intuitions about adjunct clauses. It is, however, unclear whether the self-reported proficiency in Danish covers, e.g., speaking, understanding spoken language, reading, or all the above, given that we only had one measure for overall proficiency. Some of the variation attested in the experiment may thus also be the result of the participants differing in their receptive and expressive proficiencies in a way that we are not able to control for in the analysis.

In addition, one might speculate whether the performance in L2 Danish actually constitutes transfer, or whether it might simply be the case that second-language speakers fail to identify syntactic islands due to a general L2 processing effect. As shown in

Figure 3, proficiency is correlated with increased acceptability, which may suggest that, with increased proficiency, it is easier to processes the high complexity involved in such extractions. This is the opposite pattern of what we would expect if there were parameter resetting or grammar restructuring in the L2 speakers, given that Danish L1 speakers found extraction from adjunct clauses significantly worse than English L1 speakers did. Ultimately, this suggests that processing demands may explain some of the variation in our data.

The results of this experiment can potentially shed light on the underlying nature of island constraints and their limits. In past research, we have hypothesized that Danish (along with other Mainland Scandinavian languages) may have a ‘deeper’, more complex functional syntactic structure which allows extraction to occur more freely than in other languages like English by providing an ‘escape hatch’ that circumvents the restrictions imposed by island constraints (cf.

Section 1), thus enabling extraction from embedded questions and relative clauses (e.g.,

K. R. Christensen et al., 2013a,

2013b;

K. R. Christensen & Nyvad, 2019;

Nyvad et al., 2017;

Vikner et al., 2017). In such a case, L1 Danish users would encounter a reduction in syntactic complexity when learning English as a second language, while L1 English users learning Danish would be exposed to a new level of complexity, especially when it comes to island structures. However, it is not clear that adjunct clauses involve the same type of functional structure. Indeed, the findings of the present study, in conjunction with

Nyvad et al. (

2022,

2024), suggest that the nature of extraction from adjunct clauses is different from extraction from other types of clauses. Given that the differences between Danish L1, English L1, and Danish L2 appear to be a matter of degree rather than category, it is difficult to maintain that there is a parametric difference between Danish and English.

More generally, these studies also call into question the very nature of island constraints. Universalist structural accounts (

Chomsky, 1973;

Lasnik & Saito, 1984;

Phillips, 2013a,

2013b) argue that syntactic constraints on long-distance dependencies are innate and hence invariable and inviolable universal principles of grammar. As a result, gradience in acceptability as a function of manipulations in non-structural factors is not expected, nor is variation across constructions, and crosslinguistic uniformity is predicted (cf.

Liu et al., 2022). In other words, the universalist structural accounts struggle with data like the ones in the present study, as we have attested variation across, e.g., Danish L1 and Danish L2, as well as variation across the three different adjunct clause types. However, some syntactic theories of islands introduce the notion of strength of violation through grammatical constraints (

Huang, 1982;

Chomsky, 1973,

1986). In fact, while island constraints were originally conceptualized as being grammatical in nature, it has been argued that they may actually have their origins in processing demands (

Hawkins, 1999,

2004), and island effects can be viewed as epiphenomena (domain-general) rather than the product of innate grammatical island constraints (domain-specific). If acceptability levels vary simply as a function of manipulations of non-structural factors, then it stands to reason that island effects cannot be explained purely in terms of syntax.

In short, the present study suggests, perhaps not unexpectedly, that there may not be a single parameter for adjunct islands that is transferred (e.g., a parameterized version of the CED or the addition of an extra functional layer), but rather that L2 speakers restructure or adjust their L2 grammars gradually, perhaps in a “property-by-property” manner (

Westergaard, 2021). This restructuring is also subject to processing constraints, as increased proficiency appears to be positively correlated with acceptability, which in turn may be taken to reflect (reduced) processing cost (

K. R. Christensen & Nyvad, 2024).

In conclusion, this study contributes valuable empirical data to the ongoing investigation into island phenomena, shedding light on the intricate nature of adjunct clause extraction from an L2 perspective, which challenges the traditional assumption that adjunct clauses are strong islands for extraction. The variation in extraction patterns observed across different adjunct clause types and across languages calls for a more fine-grained theoretical framework to account for adjunct clause extractability that can capture the factors influencing acceptability patterns across languages. Further research in this area may illuminate which island constraints are universal, and, perhaps equally important, which are not. The crosslinguistic variation in island sensitivity between Danish and English is likely the result of a complex interplay of multiple factors, including syntactic differences, discourse-functional influences, processing-based mechanisms, and language-specific constraints. Understanding the underlying reasons for this variation is a challenging task that requires further investigation and possibly the consideration of additional linguistic, cognitive, and discourse-related aspects.