Reconsidering the Social in Language Learning: A State of the Science and an Agenda for Future Research in Variationist SLA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Variationist SLA

2.1. An Overview of Variationist SLA

- Periphrastic future: Demain je vais aller à Londres. “Tomorrow I am going to go to London.”

- Inflectional future: Demain j’irai à Londres. “Tomorrow I will go to London.”

- Present indicative: Demain je vais à Londres. “Tomorrow I go to London.”

2.2. Previous L2 Variationist Research on Social Factors

3. Three Waves of Variationist Sociolinguistics

4. Other Socially Oriented Research in SLA

5. Conclusions

- (i)

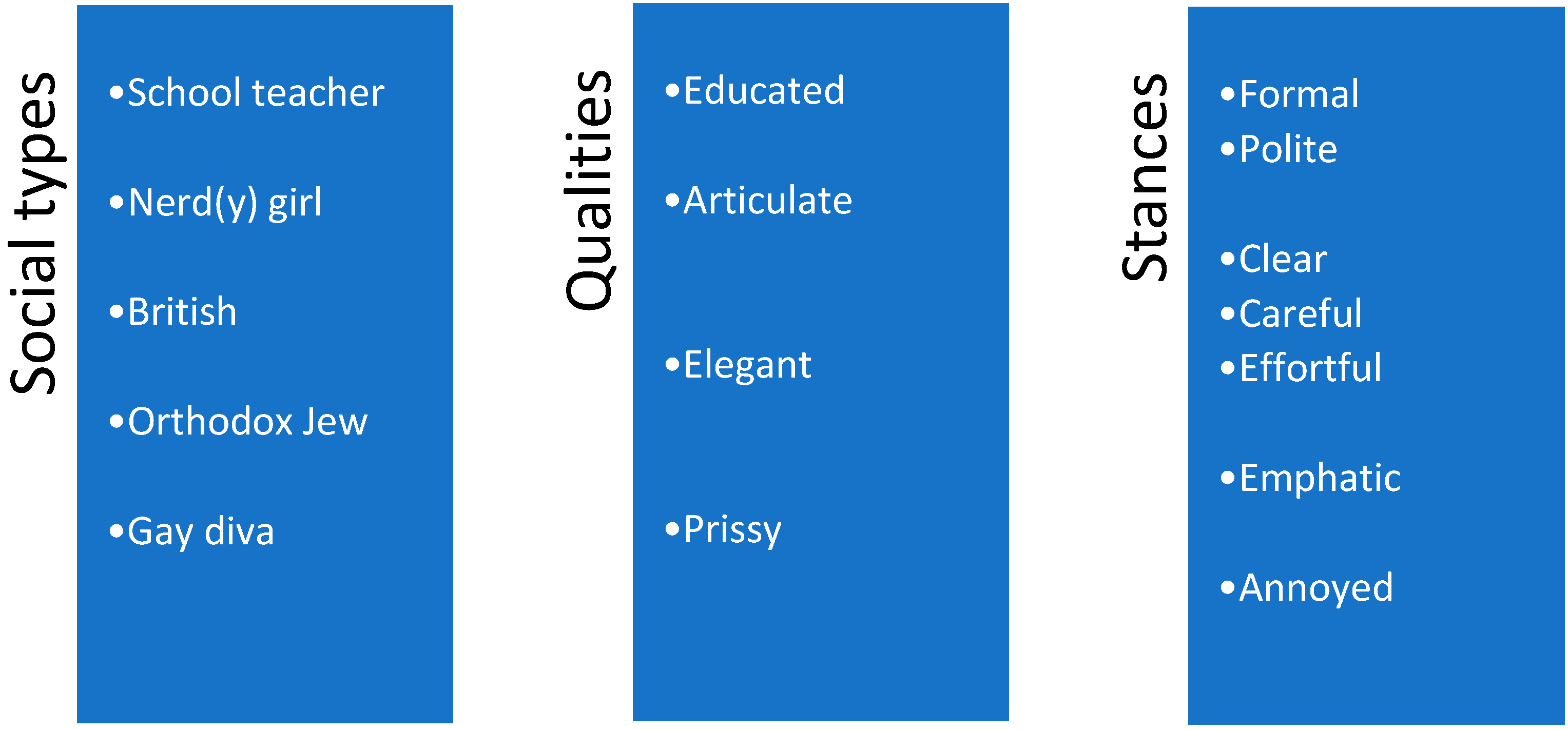

- The second and third wave of sociolinguistics and contributions from non-variationist L2 approaches show us that a critical aspect of language usage and development pertains to language users and learners themselves—the active role they play in their language behavior and the agency they have to use language to reflect their identity. For instance, with approaches informed by sociocultural theory, van Compernolle and Williams (2012) have shown how learners use variation to perform and negotiate their identities in an L2 and how the meanings they assign to variation may change over time for variables such as first-person plural and second-person singular reference and variable use of negative ne in L2 French.12 Variationist SLA has much to learn about L2 sociolinguistic competence by better incorporating the constructs of agency and identity into the investigation of variable structures and by examining these constructs along with other (extra)linguistic factors. This work could also help reveal how learner language ideologies develop and the extent to which these reflect or diverge from ideologies present in the target-language culture. In turn, how learners come to associate variable linguistic forms with locally relevant social types and how additional orders of indexicality unfold can continue to inform what we know about L2 development.

- (ii)

- Most L2 variationist research has employed quasi-experimental techniques and has been quantitative (see Regan, 2023; Wirtz et al., 2024, for recent examples of qualitative studies). While analytical tools like regression models remain valuable, the evolution of variationist sociolinguistics and other socially oriented approaches to SLA has demonstrated that ethnography and qualitative analyses shed important light on the intricacies of social factors (e.g., local categories like Burnouts and complex variables like gender identity). Thus, diversifying the research methods employed in variationist SLA appears to be a necessary step for expanding the study of the relationship between the extralinguistic nature of language and the L2 development of variable structures (see Riazi & Farsani, 2024, for a discussion of mixed-methods research in applied linguistics more generally). The aforementioned recent example of the use of virtual reality in Wirtz and Pfenninger (2024) illustrates another way in which new methods may be used to untap the role of social characteristics in language development, and the study’s dense data collection points help to reveal how sociolinguistic competence develops over time. Such repeated elicitations will contribute social information to a base of studies in L2 variationism that have tended to follow the general applied linguistics trend of largely including one-time cross-sectional or relatively limited longitudinal sampling (Ortega & Byrnes, 2008).

- (iii)

- Variationist SLA research has primarily investigated Caucasian college students. These participant pools come from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (i.e., WEIRD) societies, which are not representative of the extent of human diversity, thus raising questions about the generalizability of the knowledge that has emerged from research on this population (Henrich et al., 2010). Broadening the study of variable structures to other learner populations (see Anya, 2017) will therefore enable researchers to more fully investigate the role that social factors play in the development of sociolinguistic competence because, for one, the social and linguistic diversity that exist in the world will be more accurately represented.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In our article, usage refers to language use, interpretation, and selection (Gudmestad, 2024). See Section 2.2 for further details on the term extralinguistic. |

| 2 | In Section 3, we recognize that most variationist SLA research has corresponded to the first wave of variationist sociolinguistics (Eckert, 2008), so the terms we use to discuss this line of L2 research align with terminology of the cited authors and of the first wave. As variationist sociolinguistics has evolved (i.e., the second and third waves), so too has the conceptualization of language variation and, therefore, the rhetoric and terminology used to characterize it. |

| 3 | We do not mean to imply a strict dichotomy between work that appealed to cognition and research into social factors. Although cognitive accounts of language structure and change were considered in early analyses of L2 variation, social information and the underlying processes that link variability to cognition also have a long history in the field (e.g., Adamson & Kovac, 1981; Bayley, 1991; Dickerson, 1974; Preston, 1993; Tarone, 1988; Young, 1991). |

| 4 | In addition to variationist sociolinguistics, variationist SLA also has roots in another vein of sociolinguistics: ethnography of communication. Early contributions from this approach critically informed the aforementioned construct of sociolinguistic competence and the superordinate communicative competence (see Hymes, 1967, 1972; Paulston, 1974). |

| 5 | Topic seriousness is a contextual, sociostylistic factor that is external to the internal linguistic system (see Donaldson, 2017). |

| 6 | Native speaker is the term used most often in this line of inquiry, so we use it in the current article. We recognize, however, concerns about the role of native speakers in applied linguistics more generally (e.g., Holliday, 2006; Ortega, 2013, 2016) and variationist SLA in particular (Grammon, 2022, 2024b). |

| 7 | Type II variation can be subdivided into two categories. The most frequently investigated category pertains to linguistic structures that are variable within a given community or speaker (e.g., future-time reference in French). The other category pertains to linguistic structures that vary geographically. In these cases, categorical usage can be found within speakers or communities (e.g., the second-person plural [familiar] subject pronoun vosostros/vosotras in north-central Spain, which is generally absent in other varieties). |

| 8 | Whereas we focus on variationist research on variable structures in the current article, Wirtz and Pfenninger (2024) show that variationist approaches can also fruitfully be used to study the variable use of language varieties. |

| 9 | Although socially informed L2 variationist work has tended to consider macrodemographic characteristics in line with the first wave, early exceptions made greater use of social networks and anthropological methods that would later become hallmarks of the second and third waves. For instance, Preston (1989) highlights ethnographic backgrounds and suggests the possible consideration of classrooms as speech communities. |

| 10 | In our consideration of the presence of second and third wave variationist sociolinguistics in SLA research, we were faced with the task of objectively determining the envelope of L2 studies that fall into these waves. The approach we have adopted here is to examine how researchers describe their own work. Another approach would have been independently to classify work based on the presence of certain criteria, even if the author does not mention a particular wave. As we were interested in how researchers viewed their own work as fitting into the waves of the relevant field(s), we chose the former. |

| 11 | Although early sociolinguistic work on social networks has been described as second-wave research, the application of social network theory to variationist SLA has tended to take this approach from a first-wave perspective in its consideration of macro-demographic characteristics of learners and local residents in study-abroad contexts (e.g., Kennedy Terry, 2022). |

| 12 | Similarly, as part of sociolinguistic development, Ender (2017) has considered how learners construct identities, show alignment with local communities, and develop attitudes toward language varieties in the context of variation between standard German and what is known as Austrian Dialect. Regan (2022) has also shown how learners’ identities and attitudes and ideologies toward the L2 help to shape their development of a sociolinguistic repertoire with respect to variable deletion of the French negative particle ne. |

References

- Adamson, H. D., & Kovac, C. (1981). Variation theory and second language acquisition data: An analysis of Schumann’s data. In D. Sankoff, & H. Cedergren (Eds.), Variation omnibus (pp. 285–292). Linguistic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, H. D., & Regan, V. M. (1991). The acquisition of community speech norms by Asian immigrants learning English as a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, H. S., Rickford, J., & Ball, A. (Eds.). (2016). Raciolinguistics: How language shapes our ideas about race. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anya, U. (2017). Racialized identities in second language learning: Speaking blackness in Brazil. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, D. (2011). Introduction: Cognitivism and second language acquisition. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 1–23). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, R. H. (2014). Multivariate statistics. In R. J. Podesva, & D. Sharma (Eds.), Research methods in linguistics (pp. 337–372). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, R. (1991). Variation theory and second language learning: Linguistic and social constraints on interlanguage tense marking [Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University]. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley, R., & Tarone, E. (2012). Variationist perspectives. In S. M. Gass, & A. Mackey (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 41–56). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, R., Preston, D. R., & Li, X. (Eds.). (2022). Variation in second and heritage languages: Crosslinguistic perspectives. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, Harriet Wood. (2016). Assessing second language oral proficiency for research: The Spanish elicited imitation task. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 38, 647–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, K. (2011). Intersecting variables and perceived sexual orientation in men. American Speech, 86, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, H. R. (2021). Thickening language and sexuality studies: Multilingualism, race/ethnicity, and queerness. Journal of Language and Sexuality, 10, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, L. (1974). Internal and external patterning of phonological variability in the speech of Japanese learners of English: Toward a theory of second-language acquisition [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois]. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, B. (2017). Negation in near-native French: Variation and sociolinguistic competence. Language Learning, 67, 141–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, P. (1989a). Jocks and burnouts: Social categories and identity in the high school. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, P. (1989b). The whole woman: Sex and gender differences in variation. Language Variation and Change, 1, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, P. (2000). Linguistic variation as social practice. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, P. (2008). Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 12, 453–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, P. (2012). Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, P. (2018). Meaning and linguistic variation: The third wave in sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (1992). Think practically and look locally: Language and gender as community-based practice. Annual Review of Anthropology, 21, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2007). Putting communities of practice in their place. Gender and Language, 1, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, A. (2017). What is the target variety? The diverse effects of standard—Dialect variation in second language acquisition. In G. De Vogelaer, & M. Katerbow (Eds.), Acquiring sociolinguistic variation (pp. 155–184). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Brasdefer, J. C., & Shively, R. L. (Eds.). (2021). New directions in second language pragmatics. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, A., & Wagner, J. (1997). On discourse, communication, and (some) fundamental concepts in SLA research. The Modern Language Journal, 81, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2019). Bringing race into second language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 103(S1), 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatbonton, E., Trofimovich, P., & Magid, M. (2005). Learners’ ethnic group affiliation and L2 pronunciation accuracy: A sociolinguistic investigation. TESOL Quarterly, 39, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeslin, K. L. (2011). Variation in L2 Spanish: The State of the Discipline. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics, 5, 461–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeslin, K. L. (2020). Variationist perspective(s) on interlocutor individual differences. In L. Gurzynski-Weiss (Ed.), Cross-Theoretical Explorations of Interlocutors and Their Individual Differences (pp. 127–157). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeslin, K. L., & Fafulas, S. (2012). Variation of the simple present and present progressive forms: A comparison of native and non-native speakers. In K. L. Geeslin, & M. Díaz-Campos (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 14th hispanic linguistics symposium (pp. 179–196). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, K. L., & Long, A. Y. (2014). Sociolinguistics and second language acquisition: Learning to use language in context. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammon, D. (2022). Es un mal castellano cuando decimos ‘Su’: Language instruction, raciolinguistics ideologies and study abroad in Peru. Linguistics and Education, 71, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammon, D. (2024a). Ideology, indexicality, and the second language development of sociolinguistic perception during study abroad. L2 Journal, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammon, D. (2024b). Inappropriate identities: Racialized language ideologies and sociolinguistic competence in a study abroad context. Applied Linguistics, amae003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmestad, A. (2012). Acquiring a variable structure: An interlanguage analysis of second-language mood use in Spanish. Language Learning, 62, 373–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmestad, A. (2024). Usage and variationist approaches to SLA. In K. McManus (Ed.), Usage in second language acquisition: Critical reflections and future directions (pp. 67–86). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmestad, A., & Edmonds, A. (2023). The variable use of first-person-singular subject forms during an academic year abroad. In S. L. Zahler, A. Y. Long, & B. Linford (Eds.), Study abroad and the second language acquisition of sociolinguistic variation in Spanish (pp. 266–290). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmestad, A., Edmonds, A., Donaldson, B., & Carmichael, K. (2020). Near-native sociolinguistic competence in French: Evidence from variable future-time expression. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 23, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Lew, L., Moore, E., & Podesva, R. J. (Eds.). (2021). Social meaning and linguistic variation: Theorizing the third wave. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The meaning of style. Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the word? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, R. (2003). The german address system: Binary and scalar at once. In I. Taavitsainen, & A. H. Jucker (Eds.), Diachronic perspectives on address term systems (pp. 401–425). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, A. (2006). Native-speakerism. ELT Journal, 60, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymes, D. (1967). Models of the interaction of language and social setting. Journal of Social Issues, 23, 8–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In B. Pride, & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected readings (pp. 269–293). Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, J. T., & Gal, S. (2000). Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In P. V. Kroskrity (Ed.), Regimes of language: Ideologies, polities, and identities (pp. 35–83). School of American Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwit, M. (2017). What we gain by combining variationist and concept-oriented approaches: The case of acquiring spanish future-time expression. Language Learning, 67, 461–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, M. (2022). Sociolinguistic competence: What we know so far and where we’re heading. In K. Geeslin (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and sociolinguistics (pp. 30–44). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, M., & Solon, M. (2013). Acquiring variation in future-time expression abroad in Valencia, Spain and Mérida, Mexico. In J. Cabrelli, G. Lord, A. de Prada Pérez, & J. E. Aaron (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 16th hispanic linguistic symposium (pp. 206–221). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Terry, K. (2022). At the intersection of SLA and sociolinguistics: The predictive power of social networks during study abroad. The Modern Language Journal, 106, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesling, S. F. (2024). Doing gender in interaction. In S. F. Kiesling (Ed.), Language, gender, and sexuality: An introduction (2nd ed., pp. 88–111). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisely, K. A. (2020). Le français non-binaire: Linguistic forms used by non-binary speakers of French. Foreign Language Annals, 53, 850–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H., & Rinnert, C. (2003). Coping with high imposition requests: High vs. low proficiency EFL students in Japan. In A. Martínez, E. U. Juan, & A. Fernández (Eds.), Pragmatic competence and foreign language teaching (pp. 161–184). Servei de Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzenbacher, H. L. (2010). “Man ordnet ja bestimmte leute irgendwo ein für sich …”: Anrede und soziale deixis [“One indeed classifies certain people somewhere for himself…”: Forms of address and social deixis]. Deutsche Sprache, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantolf, J. P., Poehner, M. E., & Thorne, S. L. (2020). Sociocultural Theory and L2 development. In B. VanPatten, G. Keating, & S. Wulff (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (3rd ed., pp. 223–247). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966). The savage mind. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. [Google Scholar]

- Lybeck, K. (2002). Cultural identification and second language pronunciation of Americans in Norway. Modern Language Journal, 86, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A. R. (2019). Interpersonal factors affecting queer second or foreign language learners’ identity management in class. The Modern Language Journal, 103, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeon, R., Nadasdi, T., & Rehner, K. (2010). The sociolinguistic competence of immersion students. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C. D. (2010). A gay immigrant student’s perspective: Unspeakable acts in the language class. TESOL Quarterly, 44, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L. (2013). SLA for the 21st century: Disciplinary progress, transdisciplinary relevance, and the Bi/multilingual turn. Language Learning, 63, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L. (2016). Multi-competence in second language acquisition: Inroads into the mainstream? In V. Cook, & L. Wei (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multi-competence (pp. 50–76). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L., & Byrnes, H. (2008). Theorizing advancedness, setting up the longitudinal research agenda. In L. Ortega, & H. Byrnes (Eds.), The longitudinal study of advanced L2 capacities (pp. 281–300). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Paulston, C. B. (1974). Linguistic and communicative competence. TESOL Quarterly, 8, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picoral, A., & Carvalho, A. M. (2020). The acquisition of preposition+article contractions in L3 Portuguese among different L1-speaking learners: A variationist approach. Languages, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podesva, R. J. (2007). Phonation type as a stylistic variable: The use of falsetto in constructing a persona. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 11, 478–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D. R. (1989). Sociolinguistics and second language acquisition. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, D. R. (1993). Variation linguistics & SLA. Second Language Research, 9, 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, D. R. (2000). Three kinds of sociolinguistics and SLA: A psycholinguistic perspective. In B. Swierzbin, F. Morris, M. Anderson, C. Klee, & E. Tarone (Eds.), Social and cognitive factors in second language acquisition: Selected proceedings of the 1999 second language research forum (pp. 3–30). Cascadilla. [Google Scholar]

- Raish, M. (2015). The acquisition of an Egyptian phonological variant by U.S. students in Cairo. Foreign Language Annals, 48, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, V. (2022). Variation, identity and language attitudes. In R. Bayley, D. R. Preston, & X. Li (Eds.), Variation in second and heritage languages (pp. 253–278). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, V. (2023). L1 and L2 language attitudes: Polish and Italian migrants in France and Ireland. Languages, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, V., Howard, M., & Lemée, I. (2009). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence in a study abroad context. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, K. (2002). The development of aspects of linguistic and discourse competence by advanced second language learners of French [Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto]. (Dissertation Abstracts International S63 12). [Google Scholar]

- Riazi, A. M., & Farsani, M. A. (2024). Mixed-methods research in applied linguistics: Charting the progress through the second decade of the twenty-first century. Language Teaching, 57, 143–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauntson, H. (2020). Researching language, gender and sexuality: A student guide. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M. (2003). Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. Language and Communication, 23, 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smakman, D. (2022). Postmodern classroom language learning. In K. Geeslin (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and sociolinguistics (pp. 302–314). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, M., & Kanwit, M. (2022). New methods for tracking development of sociophonetic competence: Exploring a preference task for Spanish/d/Deletion. Applied Linguistics, 43, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, R. L. (2023). Investigating communicative competence in ethnographic research. In M. Kanwit, & M. Solon (Eds.), Communicative competence in a second language: Theory, method, and applications (pp. 79–97). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarone, E. (1988). Variation in interlanguage. Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Tarone, E. (2000). Still wrestling with ‘context’ in interlanguage theory. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, M. (1998). Introduction: A cognitive-functional perspective on language structure. In M. Tomasello (Ed.), The new psychology of language: Cognitive and functional approaches to language structure (Vol. 1, pp. vii–xxxi). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- van Compernolle, R. A., & Williams, L. (2012). Reconceptualizing sociolinguistic competence as mediated action: Identity, meaning-making, agency. The Modern Language Journal, 96, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, M. A., & Pfenninger, S. E. (2024). Capturing thresholds and continuities: Individual differences as predictors of l2 sociolinguistic repertoires in adult migrant learners in Austria. Applied Linguistics, 45, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, M. A., Pfenninger, S. E., Kaiser, I., & Ender, A. (2024). Sociolinguistic competence and varietal repertoires in a second language: A study on addressee-dependent varietal behavior using virtual reality. The Modern Language Journal, 108, 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. (1991). Variation in interlanguage morphology. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Jocks | Burnouts |

|---|---|---|

| Clothing | Pastel-colored | Dark-colored |

| Smoking habits | Do not smoke cigarettes | Smoke cigarettes |

| School activities | Involvement in school sports and clubs | Rejection of school extracurriculars |

| Spatial orientation | Occupy school facilities (eating lunch in the cafeteria, storing belongings in lockers) | Prefer school spaces less central to school life (courtyard, parking lot) |

| Cue | Description | Example |

| Salient indicators | Possible signifiers of classmates’/teachers’ acceptance of LGBT individuals | Status as young, a woman |

| Insider evidence | Comments and actions regarding acceptance of LGBT individuals | Facial expressions, use of outdated terms |

| Explicit statements | Overt declaration of acceptance | Pre-semester survey with such a statement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gudmestad, A.; Kanwit, M. Reconsidering the Social in Language Learning: A State of the Science and an Agenda for Future Research in Variationist SLA. Languages 2025, 10, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040064

Gudmestad A, Kanwit M. Reconsidering the Social in Language Learning: A State of the Science and an Agenda for Future Research in Variationist SLA. Languages. 2025; 10(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleGudmestad, Aarnes, and Matthew Kanwit. 2025. "Reconsidering the Social in Language Learning: A State of the Science and an Agenda for Future Research in Variationist SLA" Languages 10, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040064

APA StyleGudmestad, A., & Kanwit, M. (2025). Reconsidering the Social in Language Learning: A State of the Science and an Agenda for Future Research in Variationist SLA. Languages, 10(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040064