1. Introduction

A “filler–gap” dependency occurs when a wh-phrase or another nominal element (the filler) is displaced from its canonical position in a sentence. In turn, this displaced nominal element must be linked to another position in the sentence (the gap) in order to be properly interpreted. At the gap site, the filler fulfills its grammatical role as required by the verb or another predicate, such as serving as the object of the verb. For instance, in (1), the filler who is interpreted as the object of saw, even though it appears at the beginning of the sentence and is separated from its original canonical position by an embedded clause. Such dependencies that span across a clause boundary are referred to as long-distance dependencies.

- (1)

Who did Mary say that John saw __ at the party?

A central question in psycholinguistic research is when and how comprehenders resolve these long-distance dependencies during real-time sentence processing. In the types of structures most commonly investigated, namely wh-questions and relative clauses, the filler typically appears at the beginning of the sentence, while the gap is encountered later in the linear sequence. This raises an important question: Do comprehenders attempt to link the filler to a gap as early as possible during parsing of the sentence structure, adopting what has been termed an active resolution strategy, or do they instead wait until additional structural evidence becomes available, following a wait-and-see strategy? This issue has motivated the development of several distinct theoretical accounts of sentence processing.

One influential account is the

Active Filler Strategy (

Frazier, 1987), which proposes that upon encountering a displaced filler, such as a wh-word, comprehenders actively search for the earliest grammatically permissible gap site to interpret the filler. In other words, they attempt to identify a gap where the filler can be assigned its syntactic role (e.g., subject or object) as soon as the parser encounters a position compatible with that role, without waiting for further confirmation. This assumption is supported by studies on the Active Gap-Filling Hypothesis (

Crain & Fodor, 1985;

Stowe, 1986), which indicate that listeners attempt to link a wh-phrase to a gap as soon as a grammatically licit position becomes available. Processing difficulty arises when the predicted gap site is unexpectedly filled by an overt noun phrase. For example, in (2),

who is initially expected to be the object of

bring, but this expectation is violated when the direct object

us appears, forcing comprehenders to revise their initial interpretation.

- (2)

My brother wanted to know who Ruth will bring us home to __ after the party.

Much of the empirical support for the Active Filler Strategy derives primarily from studies conducted in head-initial languages like English. In these languages, comprehenders often show an early preference for main clause (MC) interpretations when processing structurally ambiguous wh-questions. For example, in (3), the wh-word

where can be interpreted as referring either to the location of the “telling” event (i.e., MC interpretation) or to the location of the butterfly-catching event (i.e., embedded clause (EC) interpretation). Using methodologies such as self-paced reading and eye-tracking, previous studies have shown that English speakers typically favor the MC interpretation, consistent with a bias toward early gap resolution (

Traxler & Pickering, 1996). Similar findings have been reported in other head-initial languages such as German (

Gibson, 1998).

- (3)

Where did Lizzie tell someone that she was going to catch butterflies?

Although previous findings support the view that comprehenders resolve wh-dependencies as early as possible, a critical question remains: What guides this early commitment in filler–gap dependency resolution? Two possible explanations have been proposed, one based on hierarchical syntactic structure and the other on linear locality constraints. The first account suggests that comprehenders prioritize syntactically more prominent positions, resolving dependencies in higher structural positions, such as the matrix clause, whenever possible. For example, in a sentence like (3), comprehenders may interpret the wh-phrase

where as referring to the location of the matrix verb

tell, rather than the embedded verb

catch. This preference for MC interpretations aligns with parsing theories that emphasize structural simplicity and grammatical prominence (

Frazier & Fodor, 1978;

Frazier, 1987). According to this view, comprehenders favor interpretations that involve fewer levels of clausal embedding because these require fewer processing resources and reflect the syntactic hierarchy of the sentence. In this framework, the matrix clause, being structurally higher, serves as a default attachment site for the filler. Thus, when comprehenders encounter a wh-phrase, they initially attempt to resolve the dependency within the main clause before considering more deeply embedded clauses.

In contrast, the locality-based account argues that the dependency resolution is guided by linear proximity. Comprehenders are assumed to favor gap positions that are closer to the wh-phrase in the surface order, thereby minimizing the working memory demands associated with maintaining an unresolved dependency. A prominent formalization of this idea is the

Dependency Length Minimization Hypothesis (

Gibson, 1998), which posits that dependencies involving shorter linear distances between syntactically related elements are easier to process than those involving longer distances (

Gibson, 2000;

Lewis & Vasishth, 2005). According to the Dependency Locality Theory, even when dependencies are not structurally simpler in terms of hierarchical embedding, that is, when the filler must be linked to a deeply embedded position in the syntactic tree, they can still be easier to process if the surface linear distance is short, as measured by the number of intervening discourse referents or syntactic heads between the filler and the gap.

Importantly, while structural and locality-based accounts offer competing explanations for how filler–gap dependencies are resolved, both are compatible with the Active Filler Strategy, which posits that comprehenders attempt to resolve dependencies as early as possible, at least in English. This convergence arises because, in English, the preference for resolving the dependency at the MC site aligns with predictions from both theoretical perspectives. Specifically, the matrix gap site, such as the verb tell in example (3), is both structurally higher in the syntactic structure and linearly closer to the filler than the embedded verb catch. As a result, evidence from English alone does not allow us to disentangle whether early gap resolution is primarily guided by syntactic structure or by linear proximity.

Japanese, in contrast, provides an ideal test case for teasing apart these two accounts. Owing to its complement clause structure, Japanese reverses the linear order of embedded and main clauses. For example, the English sentence (3) corresponds to the Japanese structure in (4). In this construction, the EC choucho-o tsukamaeta (caught butterflies) precedes the MC verb iimashita (told). This word order creates a configuration in which the predictions of the structural and locality-based accounts come into direct conflict. In sentences like (4), the structural account predicts that comprehenders will associate the filler (Doko, where) with the syntactically higher MC verb (iimashita, told), while the locality-based account predicts that the dependency will be resolved at the linearly closer EC verb (tsukamaeta, caught).

- (4)

Doko-de Lizzie-wa [pro choucho-o tsukamaeta to] iimashita-ka?

Where-at Lizzie-TOP[pro butterfly-ACC catch-PST COMP] tell-PST-Q

“Where did Lizzie tell (someone) she was going to catch butterflies?”

In fact, this precise contrast was empirically tested by

Aoshima et al. (

2004). They conducted a series of self-paced reading experiments using Japanese wh-question sentences as in (5), where the EC precedes the MC. Their results revealed increased reading times at the EC verb and complementizer sequence (

yonda-to, “read”), which they interpreted as a filler–gap effect, indicating that comprehenders had attempted to associate the fronted wh-phrase (

Dono seito-ni, to which student) with a gap in the EC, resolving the filler–gap dependency at the linearly closer site. These findings support a locality-based account, according to which dependency resolution is guided by linear proximity rather than structural locality.

- (5)

Dono-seito-ni tannin-wa Koocyoo-ga hon-o yonda-to tosyositu-de sisyo-ni iimasita-ka?

Which student-DAT class teacher-TOP principal-NOM book-ACC read-DeclC library-AT librarian-DAT told-Q

‘Which student did the class teacher tell the librarian at the library that the principal read a book for?

Similarly,

Omaki et al. (

2014) conducted a study investigating the interpretation of Japanese wh-questions as in sentence (4), which provides a particularly transparent contrast with their English counterparts due to the reversal of EC and MC order. While

Aoshima et al. (

2004) focused on real-time processing in Japanese, Omaki et al. extended this line of work by directly comparing offline interpretations across Japanese and English using sentence structures that were syntactically simpler and lacked additional embeddings, in order to isolate cross-linguistic differences in filler–gap resolution preferences. Consistent with Aoshima et al.’s findings, Omaki et al. found that Japanese participants interpreted the wh-phrases as being associated with the EC, rather than the MC. This pattern suggests that when comprehenders encounter a wh-phrase, they attempt to resolve it at the first grammatically licit gap site they encounter in the linear order of the sentence, even if that site is structurally deeper in the syntactic tree. In other words, rather than prioritizing structurally higher syntactic tree sites like the MC, Japanese speakers show a preference for resolving filler–gap dependencies in the linearly closer clause, which challenges theories that emphasize structural hierarchy. Taken together, the results from these studies support the view that active gap filling may be more strongly influenced by linear locality rather than by syntactic prominence.

However, this view is at odds with insights from Japanese linguistic theory (e.g.,

Kuno, 1973;

Hoji, 1985;

Miyagawa, 2010), which emphasizes the central role of case-marking particles and clause-final elements in determining syntactic relationships. Unlike English, where word order is the primary cue to syntactic structure, Japanese relies heavily on morphosyntactic markers such as case particles (e.g., -

ga for nominative, -

o for accusative, -

ni for dative) and complementizers (such as

to,

ka) to signal argument structure and clause type. As

Saito (

2021) points out, Japanese wh-phrases such as

doko (where) are not morphologically marked for interrogative use and can appear in both questions and non-questions, as illustrated in (6b). From this perspective, the interrogative status of a wh-phrase is not determined until the comprehender encounters a licensing element, typically a clause-final question particle such as

ka, as in (4), (5), and (6a).

- (6)

a. Doko-ni ikimasu-ka? (Where are you going?)

b. Doko-ni ikutomo iwanakatta. ((Someone) did not tell where he was going.)

This theoretical perspective suggests that these typological features of Japanese may influence how speakers process wh-questions. Unlike English wh-phrases such as what or where, which are unambiguously marked for interrogative force and typically appear in sentence-initial position, Japanese wh-phrases like doko (where) are not morphologically marked for interrogative use. Consequently, Japanese listeners must rely on downstream morphosyntactic cues that appear later in the sentence, particularly the clause-final question particles -ka, to determine the utterance is interrogative. This delayed availability of interrogative force may, in turn, lead Japanese comprehenders to withhold full commitment to a gap site until the sentence-final position.

If these morphosyntactic constraints are taken into account, previous findings suggesting an EC preference (e.g.,

Aoshima et al., 2004;

Omaki et al., 2014) may warrant re-evaluation. While these studies have often been interpreted as supporting a linear proximity account, alternative interpretations of their results remain equally plausible. In particular, the increased reading times observed at the EC verb and complementizer in

Aoshima et al.’s (

2004) study do not necessarily reflect early structural commitment to a gap site in the EC. One possibility, acknowledged by

Aoshima et al. (

2004) themselves, is that participants initially expected the wh-phrase to be associated with the MC, and the appearance of the EC triggered a revision of this expectation.

Another possibility is that the increased reading times at the EC verb reflect not active gap formation but rather the absence of sufficient morphosyntactic cues to support a stable structural commitment. Under this interpretation, comprehenders may have temporarily withheld assigning a dependency, postponing structural commitment until more disambiguating information such as clause-final morphology became available later in the sentence. Thus, the increased reading time may reflect interpretative uncertainty or hesitation, rather than conclusive evidence of an early gap-filling in the EC. As for

Omaki et al.’s (

2014) results, their findings were based on end-of-sentence comprehension tasks, which reflect participants’ final interpretations rather than the incremental time courses by which those interpretations are derived. As such, their data do not provide direct evidence for early gap-filling or active dependency resolution during incremental processing.

To address these limitations and more directly investigate the time course of dependency resolution, the present study adopted a visual world eye-tracking paradigm (

Altmann & Kamide, 2004). This method provides a temporally fine-grained and naturalistic approach to examining wh-dependency resolution in real time. Unlike self-paced reading, which provides only isolated reading times at descrete sentence regions, eye-tracking continuously captures moment-by-moment shifts in participants’ visual attention as they process spoken language. In addition to the key-press response data recorded at the end of each trial, which index participants’ final interpretations, the eye-tracking data allow us to examine not only which interpretation comprehenders ultimately adopt (EC vs. MC), but also when such interpretive preferences begin to emerge during sentence processing. A more detailed description of the experimental procedure is provided below.

In addition to using the fine-grained temporal resolution of eye-tracking, we also employed a cluster-based permutation analysis to examine the time course of wh-dependency resolution. This non-parametric approach allowed us to assess the reliability of observed effects across time without relying on pre-defined analysis windows. By combining this analytic method with temporally sensitive data, we tested whether Japanese wh-dependency resolution reflects early structural commitment or later revision, and whether it is guided more strongly by hierarchical syntactic structure than by linear proximity.

4. Discussion

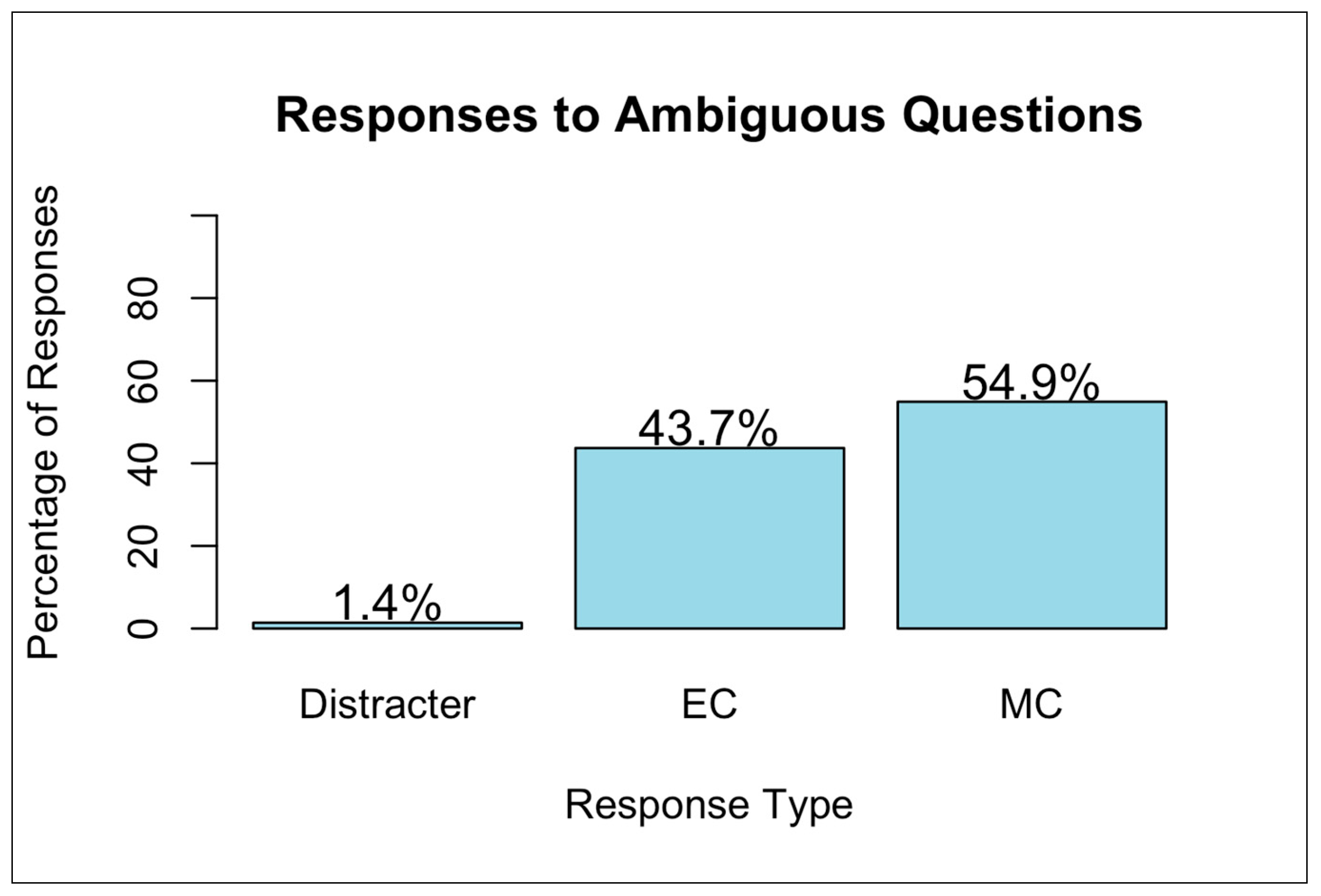

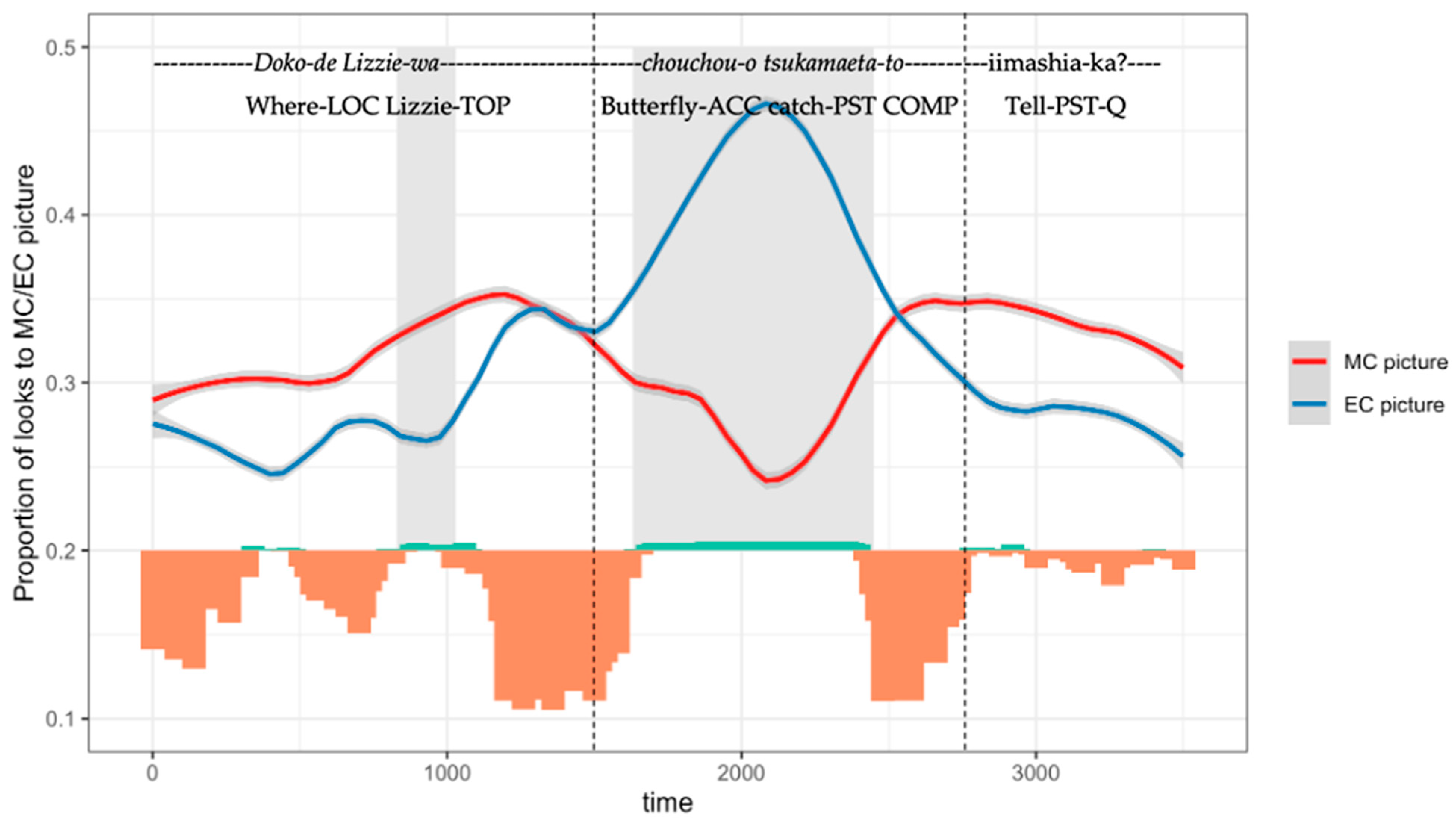

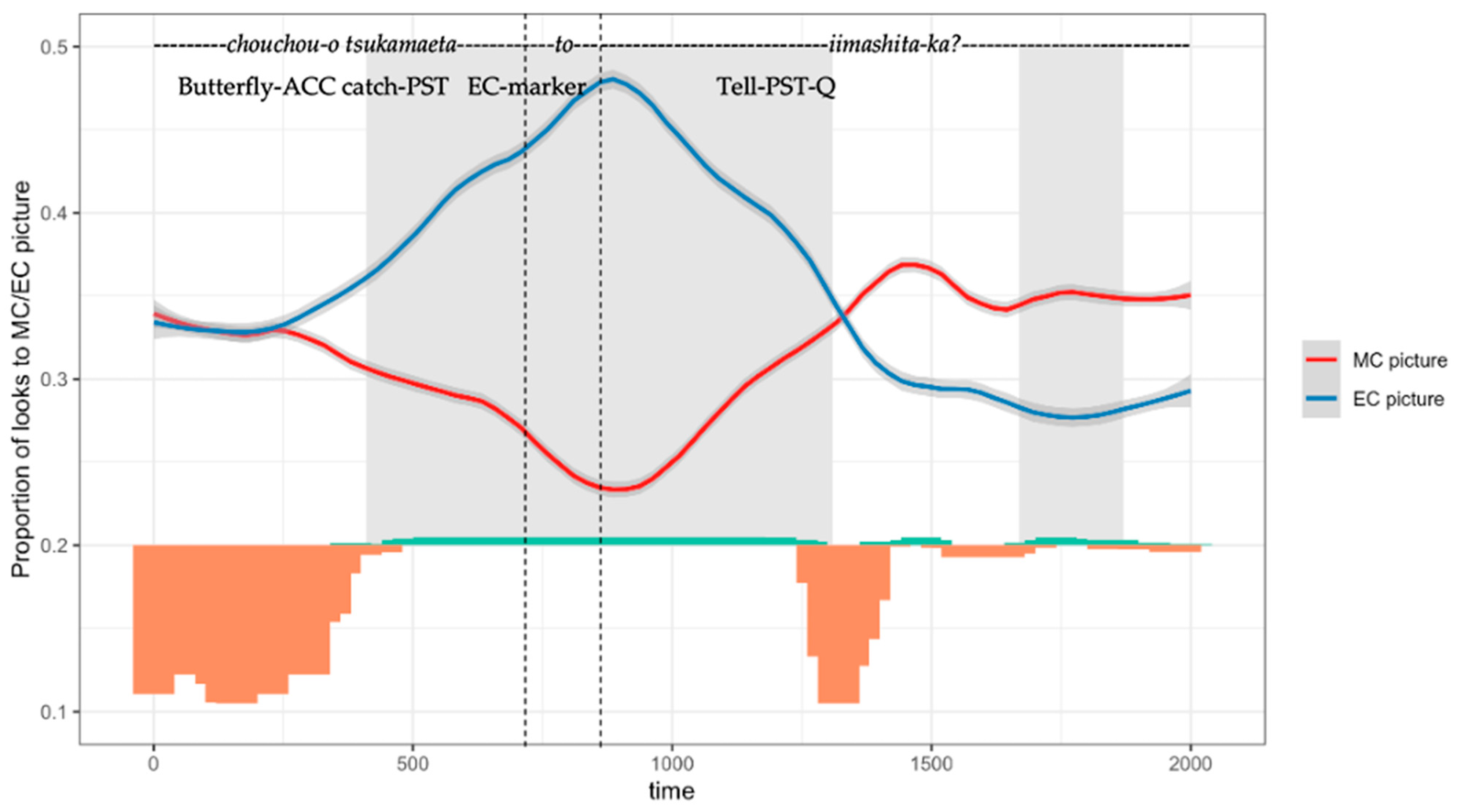

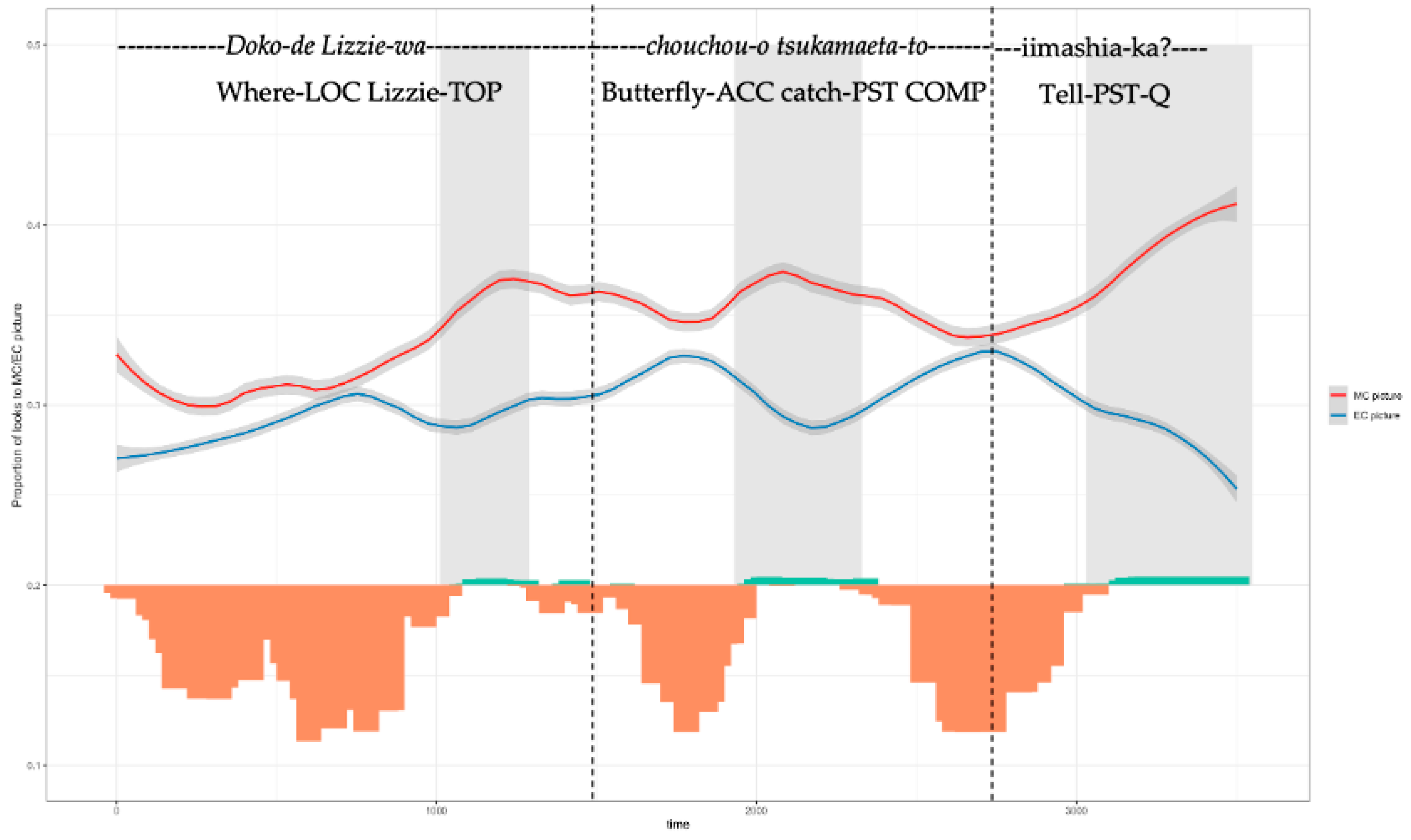

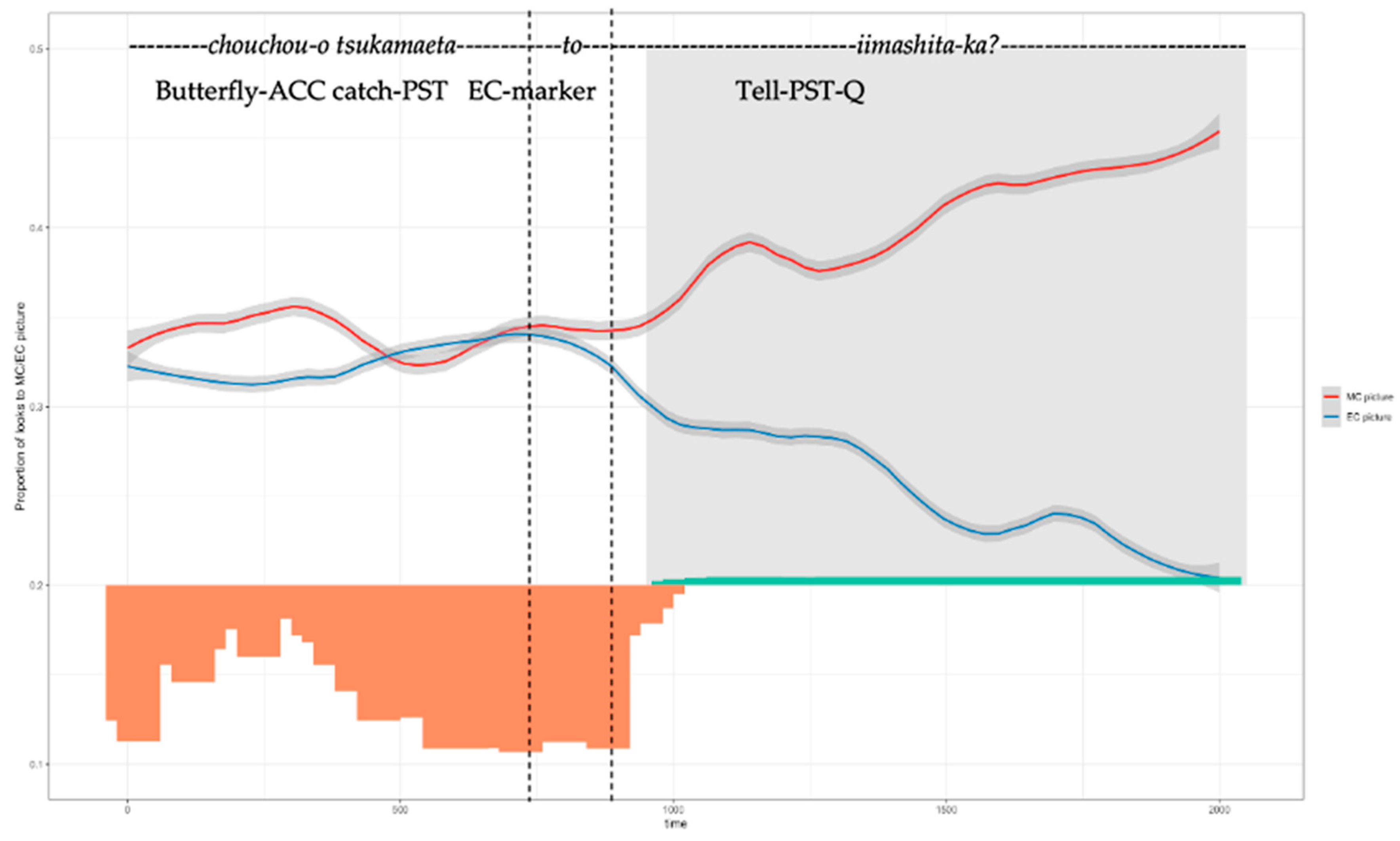

The present study examined how Japanese speakers interpret structurally ambiguous wh-questions, aiming to distinguish between two competing accounts of filler–gap resolution: one based on structural locality and the other on linear locality. Specifically, we investigated how listeners resolve ambiguity between MC and EC interpretations in real time. Key-press responses to ambiguous wh-questions revealed a preference for the MC interpretation, indicating that Japanese speakers do not resolve filler–gap dependencies based solely on linear proximity. Eye-tracking data further illuminated the time course of processing, showing how listeners incrementally constructed their interpretation as the sentence unfolded. To capture this process, we conducted two permutation analyses. The first, a whole-sentence analysis time-locked to question onset, provided a broad view of gaze patterns in processing the entire sentence. The second analysis, time locked to the onset of the EC region and continuing through to the sentence offset, focused on a narrower time window and allowed us to isolate participants’ responses to syntactic cues that emerged later in the sentence, such as the EC marker -to and the clause-final question particle -ka.

Findings from the whole-sentence analysis revealed two temporally distinct clusters in gaze behavior. The early cluster, occurring before participants were introduced to any critical lexical elements beyond the wh-phrase doko (where) and the subject Lizzie-NOM, showed a significant increase in fixations to the MC picture. This suggests that participants initially predicted that the question would concern the MC event (e.g., the act of telling), likely due to a combination of structural biases and the greater accessibility of the verb itta (told) relative to the embedded event. Although the two event locations were counterbalanced, itta (told) consistently appeared in the final position in the context sentence, making it especially salient and readily activated at the onset of the following wh-question. Moreover, itta (told) can occur only in the MC structure in fronted wh-questions, further constraining interpretation. These factors, together with a general bias toward MC interpretations over EC, likely contributed to this early predictive preference.

The second cluster, also observed in the whole-sentence analysis, showed increased fixations to the EC picture as the EC noun phrase (chouchou-o, butterflies-ACC) became available. As discussed above, one possible interpretation of this shift is that it reflects syntactic reanalysis, with listeners revising their initial MC prediction and restructuring the sentence from an MC to an EC interpretation. Alternatively, the increased fixations to the EC picture may reflect a revision of semantic interpretation under a sustained MC analysis. In this view, listeners retained the initially adopted MC structure but updated their interpretation of the event being queried, from Where did Lizzie say? to Where did Lizzie catch butterflies?, while still treating the question as an MC construction.

To test between the two possible interpretations of the increased fixations to the EC picture, namely whether they reflect syntactic reanalysis or semantic revision under sustained MC analysis, we conducted the EC-to-sentence-final region analysis, time-locked to the onset of the EC region. This analysis confirmed that the gaze shift to the EC picture occurred well before the appearance of the EC marking complementizer -to, which explicitly marks the presence of an EC. This timing most likely suggests that listeners were initially responding to the unfolding semantic content, such as the mention of butterflies, and that the increased fixations to the EC picture are unlikely to reflect syntactic reanalysis. The observed gaze pattern implies that participants may have tentatively entertained an EC interpretation as a plausible continuation of the sentence, aligning their attention with the referential content as it emerged. However, the subsequent increase in fixations to the MC picture during the final portion of the sentence, also captured in the EC-to-sentence-final region analysis, suggests that listeners ultimately returned to or confirmed an MC interpretation. This late shift in gaze aligns with the behavioral key-press responses, which also favored MC interpretations.

Taken together, these findings indicate that while listeners are sensitive to local semantic cues during incremental processing, the structural resolution of the filler–gap dependency ultimately depends on syntactic information that emerges later in the sentence, such as the matrix verb and sentence-final question particle.

These findings have several theoretical implications. First, they challenge the view that filler–gap resolution in Japanese is guided predominantly by linear locality, as proposed in earlier studies (e.g.,

Aoshima et al., 2004;

Omaki et al., 2014). Participants temporarily shifted their gaze toward the EC picture as the EC noun phrase (

chouchou-o, butterflies-ACC) unfolded, which may suggest that they were beginning to consider an EC interpretation. Yet, because this shift occurred prior to the appearance of the EC marker -

to, it is more likely to reflect semantic revision under a sustained MC interpretation rather than syntactic reanalysis from an MC to an EC structure. The subsequent return to the MC picture, aligned with the sentence-final structural cues and mirrored in the key-press responses, indicates that participants ultimately resolved the dependency at the structurally higher MC site. These results suggest that while local linear or semantic cues may influence participants’ moment-to-moment attention, they do not override the role of structural locality in guiding filler–gap resolution.

Second, our results demonstrate that Japanese comprehenders engage in predictive processing, using contextual and morphosyntactic cues to anticipate upcoming structure. However, unlike comprehenders of languages such as English, where wh-phrases are morphologically marked, Japanese comprehenders appear to delay structural commitment until interrogative force is confirmed by sentence-final cues (e.g., clause-final particles). This pattern is consistent with accounts that emphasize the role of case-marking and clause-final particles in Japanese parsing (e.g.,

Kuno, 1973;

Miyagawa, 2010).

The observed preference for resolving dependencies at the structurally higher MC syntactic tree site provides support for accounts that posit a syntactic hierarchy bias in filler–gap resolution. These accounts propose that comprehenders preferentially attach fillers to the highest grammatically available position in the tree structure (e.g.,

Frazier & Clifton, 1989;

Phillips, 1996,

2006). Our findings in Japanese support the view that structure-based parsing preference, such as those proposed under the Minimal Attachment hypothesis (

Frazier & Fodor, 1978), operates as a general parsing principle across languages. In both English and Japanese, comprehenders prefer to resolve filler–gap dependencies at the structurally higher MC site. However, unlike English speakers, who are often shown to commit to the MC interpretation early, Japanese comprehenders delay this commitment due to typological features such as the presence of clause-final disambiguating cues. Importantly, however, the ultimate preference for MC attachment in Japanese, despite the linear proximity of the EC, provides evidence for structure-based parsing over linear locality. This interpretation is in line with other studies of Japanese sentence processing, such as

Tamaoka and Mansbridge (

2019), who examined scrambled sentences and showed that readers often revisit earlier material to establish structural coherence. Their results, like ours, suggest that Japanese parsing cannot be reduced to simple linear locality.

Finally, we consider possible reasons why our results diverge from those of

Aoshima et al. (

2004) and

Omaki et al. (

2014), who reported linear locality-based preferences for the EC interpretation in Japanese filler–gap dependency construction. One possibility is that these earlier findings reflect methodological limitations. Because the self-paced reading and end-point judgment methods employed in the earlier studies did not capture the fine-grained time course of filler–gap dependency formation, they may have conflated temporary attention to the EC, possibly driven by semantic salience or recent mention, with actual dependency resolution, as suggested by our eye-tracking data.

In particular, it is worth noting that our offline judgment task and Omaki et al.’s task produced opposite outcomes: whereas our participants showed a preference for the MC interpretation, Omaki et al. found an EC preference. We suggest that this discrepancy is likely due to differences in task design. Omaki et al.’s experiment involved long story contexts introducing four different locations sequentially before the target wh-question. Crucially, the EC location was introduced toward the end of the story, while the MC location appeared at the beginning of the context. This asymmetry makes the EC location more recent and therefore more accessible at the time participants answered the question. Given that four different locations were introduced in each story, memory load was also higher, further increasing the likelihood that participants relied on the most recently mentioned location. Moreover, their study tested only 16 participants with eight items, limiting statistical power and making the results especially susceptible to such task-specific influences.

By contrast, our design minimized narrative load, balanced the visual referents, and directly tracked online interpretations, revealing that participants ultimately resolved the dependency at the MC site. The results suggest that Japanese comprehenders do not resolve filler–gap dependencies at the earliest grammatically available position. Rather, they appear to delay commitment until reliable structural cues, such as sentence-final particles, confirm that the sentence-initial wh-phrase is being used to form a question. This pattern suggests a predictive, yet structurally cautious parsing strategy, in which comprehenders build expectations incrementally but withhold commitment until syntactic confirmation becomes available, something that earlier methods may have failed to detect.