1. Introduction

Ever since

Kendon (

2004, pp. 264–281) dedicated a section of his book to a gesture family named “Open hand supine” (i.e., with the open hand ‘on its back’), and, in the same year,

Müller (

2004) published a paper formalizing the nomenclature PUOH for palm-up open hand gestures, these gestures have been an object of interest in gesture studies, as the overview by

Cooperrider et al. (

2018) demonstrates. Most examples shown in the published research involve clear instances with the palm of the hand turned fully upward, and the fingers of the hand fully extended. However, the hand form with the palm facing directly up with fingers stretched out straight is rather effortful to produce (try it yourself!). Consequently, in some research, we see examples shown of PUOHs with the palm facing only diagonally upward and/or fingers slightly bent; and in conversations between those who are well-acquainted, as discussed below, we find many instances involving less effort, with the forearm and hand barely being turned out and/or the hand being in a relaxed, cup shape. Yet such instances often appear to be used with the same function as a PUOH. It raises the question as to whether the best term for such gestures is in fact PUOH, and also what the basis is for classifying them together if the various gesture tokens do not involve a palm up or an open hand.

The issue also raises questions for other gesture types involving recurrent use of certain forms with certain pragmatic functions in a given culture, which have been called “recurrent gestures” (

Bressem & Müller, 2014a;

Harrison & Ladewig, 2021;

Will, 2022). Examples include the family of gestures with the palm facing away from the speaker, found in German and some other cultures to be associated with different kinds of negation or refusal (

Bressem & Müller, 2014b;

Graça & Avelar, 2024;

Wu et al., 2024); or the gesture with swaying hands indicating uncertainty (

Bressem & Müller, 2014a;

Graça & Avelar, 2024). How does one decide methodologically whether the palm is pointed sufficiently away from the speaker to ‘count’ as an ‘away gesture’? Or whether the hand has swayed sufficiently to be considered a swaying gesture? There are challenges with operationalizing these types due to situational differences and individual differences in gesture production.

Below we present an approach to analyzing variants of PUOH gestures, introduced in

Section 2 and

Section 3, in terms of action schemas which can be realized with different degrees of effort, as discussed in

Section 4 and

Section 5. Specific examples from a set of elicited conversations (characterized in

Section 6) are then discussed in

Section 7. The fact that any action schema can be realized with different degrees of effort in its production, and subsequently with variations in handshape and palm orientation, means that this “palm-up puzzle” can be resolved by accounting for the variability in gesture use. This allows for a solution having greater ecological validity, as will be discussed in the conclusion in

Section 8, and has potential for application to a number of what have elsewhere been called recurrent gesture types.

2. PUOH Gestures: “The Same” Form with Several Pragmatic Functions

The idea of treating the “open hand supine” or the “palm up open hand” as a gesture family arose from

Kendon’s (

2004) and

Müller’s (

2004) assertions about these gestural forms. After extensive material collected from interactions in both English and Italian (Neopolitan),

Kendon (

2004, p. 264) proposed that “the open hand supine gesture family” can be composed of the following gestural forms:

Palm presentation gestures (moving the hand in front of the speaker as if presenting something): the speaker offers their discourse to the interlocutor (

Figure 1).

Kendon (

2004, p. 266) notes that this is typically used to “serve as an introduction to something the speaker is about to say, or serve as an explanation or comment or clarification of something the speaker has just said.” In the example in

Figure 1 (

Kendon, 2004, Figure 13.9B, p. 271), the speaker on the left had just pointed out a building on the street and when making the gesture shown, he adds, “

and it it stands up to the uh scrutiny that everything [else] calls [for in] this [beautiful little to]wn”, with square brackets being used here to indicate when the hand is held out and lowered, being lifted each time just before that, as

Kendon (

2004, p. 270) notes.

This can be seen as the classic form and function of the PUOH discussed in many studies.

Bavelas et al. (

1992) drew attention to the function of certain pragmatic gestures by defining what they call “interactive gestures,” understood as gestures that involve an interlocutor (such as the palm-up gesture used when we say “for example”). In this perspective, these gestures are not part of the propositional content of the discourse, as they are related to the way in which the discourse is presented and managed in relation to the interaction in which the speaker and the interlocutor are engaged.

Palm addressed gestures (directed to an addressee): the speaker acknowledges what the interlocutor has just said. In the example in

Figure 2, the speaker on the right had just explained how people in Naples were so hungry after World War II that they even ate weeds, including poppies. When his interlocutor is surprised at this, mentioning that poppies are supposed to be poisonous, the man says (in Neopolitan), “

L’oppio! Eee së ‘e mangiavëne!” (‘Opium! Eh they used to be eaten!’). He makes the gesture towards her when saying “

L’oppio!” (‘Opium!’), as

Kendon (

2004, p. 272) adds, “in this way acknowledging that she is right […] when she said they were poisonous”.

Given the location of the hand directly in front of the interlocutor and the orientation of the fingers straight towards the interlocutor,

Kendon (

2004, p. 271) counts this as a form of pointing. See also

Holler and Wilkin (

2009) on communicating sharing common ground with another speaker via gestures pointing at them, which they count as deictics (p. 275); the function here can be seen as part of acknowledging an interlocutor’s contribution to a conversation, as discussed by Kendon. For these reasons, this use of the PUOH is counted as a form of pointing in the present analysis.

Palm lateral gestures (moving the PUOHs apart) can serve several functions. They can show: the speaker’s inability to intervene with regard to what one’s interlocutor is saying; acceptance of something as ‘obvious’; that something suggested is a possibility which the speaker neither denies nor accepts; that the other person is free to do something; or follow a question for which one does not expect an answer (

Kendon, 2004, p. 275). “Lateral” here refers to the final position of the palm-up hands after they have moved apart, namely at the speaker’s sides.

Kendon (

2004, p. 275) describes that the laterally outward movement begins in many cases “with an outward rotation of the forearm so that one’s impression is that of the hand or hands ‘opening’ as they move apart from one another.” The context of the example illustrating the gesture in

Figure 3 is that the person’s pet turtle had fallen into a wash tub and died, and someone suggested it was because it had drunk the soapy water. The person shown responds with the given gesture without words “to indicate that the suggestion is neither accepted nor rejected”, as

Kendon (

2004, p. 280) claims. Only after making the gesture does she simply conclude (in Italian), “

è morta” (‘it is dead’) (p. 279).

According to

Cooperrider et al. (

2018, p. 4), a noticeable distinction must be made between two different types: palm-up presentational gestures (Kendon’s palm presentation gestures) and palm-up epistemic gestures (Kendon’s palm lateral gestures). (Their study did not consider Kendon’s palm-addressed category.) The former type involves a movement toward the interlocutor, as if ‘presenting’ an idea. According to the authors (

Cooperrider et al., 2018), this would be related to the

conduit metaphor, discussed by

Reddy (

1979), in which communication is conceptualized in terms of the transfer of ideas. In terms of presentational gestures, either an (invisible) idea is being offered—or in fact nothing is being offered and the empty hand shows the non-existence of some object or idea or that an object or idea is being requested. Palm-up epistemic gestures, involve a lateral separation of the hands and express evaluative meanings, or are part of a shrug, and can be related to the core meaning of “absence of knowledge”.

The distinction pointed out by

Cooperrider et al. (

2018) thus concerns both the location of the PUOH(s) and the function. While we agree with the functional distinction they pointed out, afforded by the differing movement directions in different locations in gesture space, we find in our own conversational data that many other occurrences of gesture appear to serve the same functions, and to have a relation to such uses of PUOHs, but in fact are either not palm up gestures, or do not involve open hands, or both—an issue treated in the following section.

3. The Problem: Many “PUOH Gestures” Are Not Palm Up, or Not Open Hand, or Neither

This dilemma is discussed in

Cienki (

2021), which considers the category of presentational gestures discussed above. It proposes a more integrative way of analyzing gestures serving the function of “presenting a point”. While the PUOH would be the stereotypical form, “many other gesture forms can also accompany this discursive move” (p. 17), as can be illustrated by the continuum proposed by the author, shown in

Figure 4.

The continuum comprises four gestures exhibiting different degrees of exertion in their production, that could be coherently seen as various ways of “presenting a point”, with each way entailing a different degree of prominence in doing so. This prominence is constituted for the producer in terms of the degree and kind of effort taken in the production of the gesture, and for the perceiver in terms of visual salience through the number of articulators involved and the amount of gesture space used (

Cienki, 2021). It ranges from simple finger lifts, to a small rotation outward of the lower arm and hand, to an opening of the hand and turnout to a palm diagonally pointing up, to a full PUOH, also with a turnout of the upper arm and extension from the elbow and abduction (movement laterally outward) of the upper arm from the torso. The arrows mark the motions of the bodily segments involved in each case, considered in terms of the kinesiological factors just mentioned, based on

Boutet’s (

2010,

2018) work. The point to be taken from them here is that the general function of presenting a point can be accomplished with varying degrees of effort, involving lesser or greater use of space.

The same phenomena were found in the data for the study discussed below. This applied not only to presentation gestures, but also ones involving the hands spreading apart laterally to serve an epistemic function (

Cooperrider et al., 2018). In previous work, others have noted that a turning out of the lower arms and hands might serve a similar purpose to what Kendon called palm-lateral gestures and may comprise part of the compound enactment called a shrug (

Streeck, 2009). The hand turnout has also been called a hand shrug (

Debras, 2017; cf.

Morris, 1994, pp. 137–138: “the hands shrug”) or a hand flip (

Ferré, 2011). As these names for it suggest, this gesture may not necessarily entail the hands finally being positioned laterally, despite sharing the function found with the gesture when the hands actually do end up on either side of one’s torso.

In the following section, we explain the idea of analyzing recurrent gesture form-function pairings in terms of action schemas before presenting the details of our empirical study.

4. Action Schemas to Describe Correlated Forms and Functions

Over the last decade, recurrent gestures have emerged as a promising field of investigation in gesture studies (

Ladewig, 2014,

2024). They are considered as a category that stands in-between emblems with fixed meanings and idiosyncratic ‘singular gestures’ which have representational functions that are highly dependent on the context of use for their meaning (

Cienki, 2017;

Müller, 2018). Previous research has suggested that in any given culture, people have a repertoire of such recurrent gestures at their disposal; for any such recurrent gesture, a limited set of form features is found to be related to a limited set of functions (

Bressem & Müller, 2014a). Some of them can be grouped into gesture families, each with a unified semantic core (

Kendon, 2004). For example, gestures of brushing away, sweeping away, holding away, etc.—when used with various topics in conversation and not with the physical function of brushing, sweeping, holding off, etc.—have been claimed (in the German culture, but also known in many other cultures) to share not only the formal feature of the palm of the hand facing away from the speaker, but also the function of indicating negative assessment (

Harrison, 2024)

We build here on

Müller’s (

2017) characterization that many such recurrent gestures involve an action schema. Rather than being an actual action with a physical object (such as wiping away some dust from a surface with the side of one’s hand), or an actual depiction of such an action (e.g., pantomiming how someone wiped a surface with the side of their hand), a gesture might just involve an action schema that is a simplified version of that instrumental action, a metonymic recreation of it for another purpose. So a sweeping away movement made in the air with one’s hand can serve to dismiss or reject an idea (see, e.g.,

Teßendorf, 2014). As

Müller (

2017) points out, many of the gestures that are recurrent in conversation in any culture are based on such schematized, “as if” actions, and often serve pragmatic functions (e.g., various outward movements with the palm facing away serving to express negation of various kinds). Compare

Streeck’s (

2009, esp. ch. 3) discussion of the origin of many common gestures in practical actions with objects. Such gestures may be seen as metaphorically treating ideas or topics as if objects being acted upon with the gestures (e.g., swept away, held in the hand, etc.), leading

Streeck (

2009, ch. 8) to say that such gestures involve “speech handling”. A classic example of this is the palm-up open hand gesture (PUOH), which, if presenting an idea or question to an interlocutor for consideration, acts as if an abstract object were situated in the open palm, visible to all the participants (

Müller, 2004). Compare, for example, a video clip (Cornelia Müller, personal communication) demonstrating the physical “source domain” of this gesture with a child showing his mother an insect that he had just found, displaying it on his palm-up open hand as something interesting that he wanted her to inspect.

Another motivation for action schemas comes from Zlatev’s proposal of mimetic schemas in relation to gesture use.

Zlatev (

2005, p. 334) defines mimetic schemas as “dynamic, concrete and preverbal representations, involving the body image, accessible to consciousness and pre-reflectively shared in a community”. Examples include enactments expressing actions such as

hit,

kick,

dance, or

kiss. In many cultures, one can pretend to perform such actions, and the action being imitated is considered sufficiently common to be recognized as such. One can

hit, kick, or

kiss someone or something in different ways, for example, but the schematic pattern behind each action is one that, the author proposes, would be recognizable to members of the given culture for which the mimetic schema is relevant.

The category ‘action schemas’ that we are proposing differs from mimetic schemas in several ways. One is that it covers a broader range of actions than the mimetic schemas proposed so far in the literature. In addition, the action schemas we have characterized to date are related to manual actions specifically. Other kinds of action schemas are imaginable (e.g., related to actions performed by other parts of the body), but the characterization of them will remain for future research. Furthermore, we are not tying action schemas to some of the theoretical claims made about mimetic schemas. Specifically, mimetic schemas have been claimed (

Zlatev, 2014) to have importance ontologically, as patterns that children acquire at an early stage in their development (and are thus “preverbal”); we do not make this claim about action schemas. In addition,

Zlatev (

2007) argues that mimetic schemas, as an aspect of mimesis more generally, have been important in human evolution, as a means by which early humans may have realized the link between oneself and others. We are agnostic as to whether such developmental and/or evolutionary claims apply to some or all action schemas. The main point here is that action schemas constitute simple actions that can be performed physically (here: with the hands), and the form, movement pattern, or cultural association with them can provide the motivation for their serving a pragmatic function.

5. Offering, Side-Offering, and Spreading Hands as Action Schemas

The study reported on here, described further below, concerns a broader topic, that of potentially recurrent gestures (in the sense of

Bressem & Müller, 2014a) among speakers of Russian. For that, a coding manual was developed initially applying the recurrent gesture types described in

Bressem and Müller (

2014a). The manual was then elaborated using a bottom-up technique of discovery of additional potentially recurrent form-meaning pairings. Some of these gesture types were characterized in terms of action schemas. The present article focuses on three such action schemas, namely: Offering, a sub-category of that called Side-Offering, and Spreading (of one’s hands).

The term ‘Offering’ picks up on

Müller’s (

2004) characterization of the function of the PUOH found across the variants she observed (e.g., listing of offered arguments, continuation of offered arguments, etc.). To adopt

Mittelberg’s (

2017) characterization, such gestures may merely involve a “metonymic and often rather schematic allusions” (p. 5) to the full action of offering. Thus rather than only consisting of a PUOH, we include the first three forms of presenting one’s point from

Cienki (

2021), shown in

Figure 4. That is, Offering an idea can be done in a minimal way, with a finger lift; in a somewhat more effortful way with a hand turnout; or in a more stereotypical way, with one’s open palm up and oriented toward the interlocutor. Offering was performed in a central space in front of the speaker in our data, and as described below, this is related to the discourse setting, in which the interlocutors were seated facing each other. Any movement in the gesture on the horizontal plane was usually in the sagittal axis toward the interlocutor.

In our analysis, a sub-category of Offering, which we call Side-Offering was distinguished based on its form and function. The action schema of Side-Offering is marked in its form by the gesture’s use of a peripheral space on the left or right side of the speaker, as shown in the fourth gesture in

Figure 4. Following

McNeill’s (

1992, p. 378) division of gesture space for purposes of transcription, the lateral peripheral space is that beyond the speaker’s shoulder on either side. For our purposes here we do not make a further separation of ‘extreme periphery’ as McNeill does but just count the lateral peripheral space as a whole. Given the effort involved in bringing a gesturing hand to this location, Side-Offering usually does not afford production via a simple hand turnout, as Offering might.

Both Offering and Side-Offering can be used when the speaker is presenting a point, an idea, or a question. Offering, described above, involves an appeal to the interlocutor, and is performed more centrally in what

Kendon (

1990, ch. 7) calls the participant’s “interactional segment”, the space for activity extending sagitally in front of them. Side-Offering serves a different function, namely that of mentioning a point that is tangential by being either not directly related to the current interactional space of the interlocutors or not directly connected to the discourse up to that point, as will be illustrated in the examples below.

The third action schema we consider here is that of Spreading one’s hands. The form involves a symmetrical lateral movement apart of one’s hands in front of one’s torso. While the hands may end up being palm up and open, neither of these features is an essential one of Spreading gestures. The hands (and lower arms) turn outward but need not reach a supine position. The fingers open to some degree but need not reach full extension to a flat open hand. The action may be associated semiotically with the physical context of moving one’s hands or arms apart, in a symmetrical lateral movement to open up the space in front of oneself and admit access to oneself, or to show that one is not holding or hiding anything. Pragmatically, this action can indicate notions such as showing that one is allowing for a possibility, or that one does not know for sure (i.e., that one is not metaphorically holding the answer to a question that has been asked).

These functions of the Spreading action schema can also be recognized in terms of the potential role of this manual action in the shrug. As

Streeck (

2009, p. 191) observes, “In shrugs, our bodies withdraw and retract from possible engagement.” This description applies equally well to the symmetrical lateral spreading outward of one’s hands in front of one’s torso, withdrawing the hands from possible engagement with any objects (physical, or in the sense of abstract ideas as if objects, metaphorical) in front of oneself.

Streeck (

2009, p. 191) continues, considering the pragmatic implication of such action: “This may be the reason why we understand shrugs as displays of distancing and disengagement.” As

Streeck (

2009, ch. 8),

Debras and Cienki (

2012),

Debras (

2017), and

Jehoul et al. (

2017) discuss, the shrug is a compound act, not all components of which are required in every performance of it. So Spreading of one’s hands is possible with or without shoulder lifts. Interestingly, while the works just cited mention the palm-up open hand as a possible component of shrugs, none of them point out the hands spreading as a feature of the action. Yet the hands are spread apart in the examples that each of them provides to illustrate shrugs. It is this feature of the movement that we highlight with our characterization of the action schema Spreading (of one’s hands). It is also worth noting that the English term ‘shrug’ covers various combinations of the components, whereas in Russian (and in many other languages), the closest equivalent term for the shrug concerns only the action of the shoulders (Russ.

pozhimat’ plechami ‘to squeeze one’s shoulders’). Therefore, particularly for such cultures, it is fitting to identify the act of Spreading one’s hands as its own action schema.

The analysis in

Section 7 demonstrates that each action schema did not consist of a simple use of one handshape with one palm orientation, as the descriptor PUOH would lead one to expect, but rather a range of variations, with each action schema stemming from a common underlying movement pattern.

6. Data and Methods

The data for this study consisted of ten conversations between pairs of native speakers of Russian (thus 20 participants in total, 16 female), average age 25, recorded in Moscow. The members of each pair were already well acquainted with each other. In addition to providing informed consent before recording began, participants also chose afterwards how their data could be used (i.e., whether their image and/or voice could be shown in academic presentations and publications). For the larger study (on stance-taking and gesture) that the present analysis was part of, the participants were invited to watch a short (5 min) animated video from a TED-Ed talk with a voice-over in Russian (

https://ya.ru/video/preview/5589761501200677611, accessed on 29 April 2024) concerning artificial intelligence and its possible implications for society. Following this, each pair, seated facing each other, was presented with a series of questions on a computer screen off to the side which they discussed, eliciting their views on the uses, benefits, and potential threats of AI. The average length of the conversations was 17 min. Participants were video-recorded from four angles (

Figure 5): one camera on each participant, one camera capturing both participants together, and one viewing both from overhead which allowed for seeing small movements not visible from the frontal views. The examples in our empirical analysis will show one or two quadrants of the video to allow for close-ups of the individual speakers.

Gesture analysis was performed using

ELAN (

2024, version 6.8), and involved identifying and annotating the gesture strokes, and, when they occurred, the preparation and/or post-stroke hold (

Bressem et al., 2013;

Kendon, 2004). Self-adapters were marked but not included in further analysis. A coding manual was developed for the gesture strokes, initially drawing upon the recurrent gesture types described in

Bressem and Müller (

2014a). The manual was then elaborated using a bottom-up technique of discovery of additional potentially recurrent form-meaning mappings. This was done by four researchers. To begin, all four coded three videos to compile the initial coding manual of potentially recurrent gestures. Gestures (strokes) were considered to constitute either singular gestures or potentially recurrent gestures. Following

Müller (

2010), gestures were considered ‘singular’ when form and meaning were constituted on the spot, such that the meaning was local and context-specific, holding only for the particular communicative encounter. This meant that gesture strokes not fitting this description were considered to be potentially recurrent. This category thus also included emblems (the few that occurred) as one category type.

Using the initial coding manual, the four coders divided into two teams of two, with each person coding one video. Videos were then traded between team members, with the first coder’s annotation tiers hidden using this feature of ELAN. The second coder received empty gesture stroke annotations to be filled in as either singular or potentially recurrent gestures, with the latter codable using the controlled vocabulary developed based on the coding manual. The results were then compared within each team. Differences in coding were discussed and resolved, and any remaining unresolved differences and questions were addressed in meetings with all four coders. Such meetings also considered possible additions or changes to the coding manual, which were then applied in subsequent coding. A final check of all ELAN files was performed with the final coding manual to ensure that earlier annotations conformed to the last version of the coding manual.

7. Analysis: The Three Action Schemas and Their Range of Manifestations

The results show that of the 2600 tokens of recurrent gestures counted in the dataset, the three most frequent action-schemas were in fact Offering (N = 504, 19% of the total), Side-Offering (N = 209, 8% of the total), and Spreading (N = 192 or 7% of the total). Each of these action schemas were found to be performed with different degrees of effort, resulting in a scale of forms of realization for each. Whereas the full productions involve palm-up open hands, the reduced forms use less outward rotation of the lower arm and/or less extension of the fingers, and thus less extensive use of space, with the least effortful versions entailing even less movement away from their starting rest position. More reduced versions are less fully manifested versions of action schemas. Yet the various instantiations of each action schema appear to engage the same basic function of the fully performed version, although with less salience.

To begin with Offering,

Figure 6 shows use of the action schema resulting in the fully extended form of a PUOH, with extension of the fingers opening the hand, and outward rotation of the forearm leading to a supination of the hand. The speaker has been talking about the role of emotions in relation to one’s psyche. She then appears to start a different line of reasoning, saying (in Russian), “

The human mind is trained on very minimal percentages of, well, …”) and then restarts by returning to her earlier topic—the role of emotion—and then continues from there. The Offering gesture marks her return to that topic. In the transcription of speech here and below, the syllable(s) co-occurring with the gesture stroke will be enclosed in square brackets, and those with any post-stroke hold will be underlined.

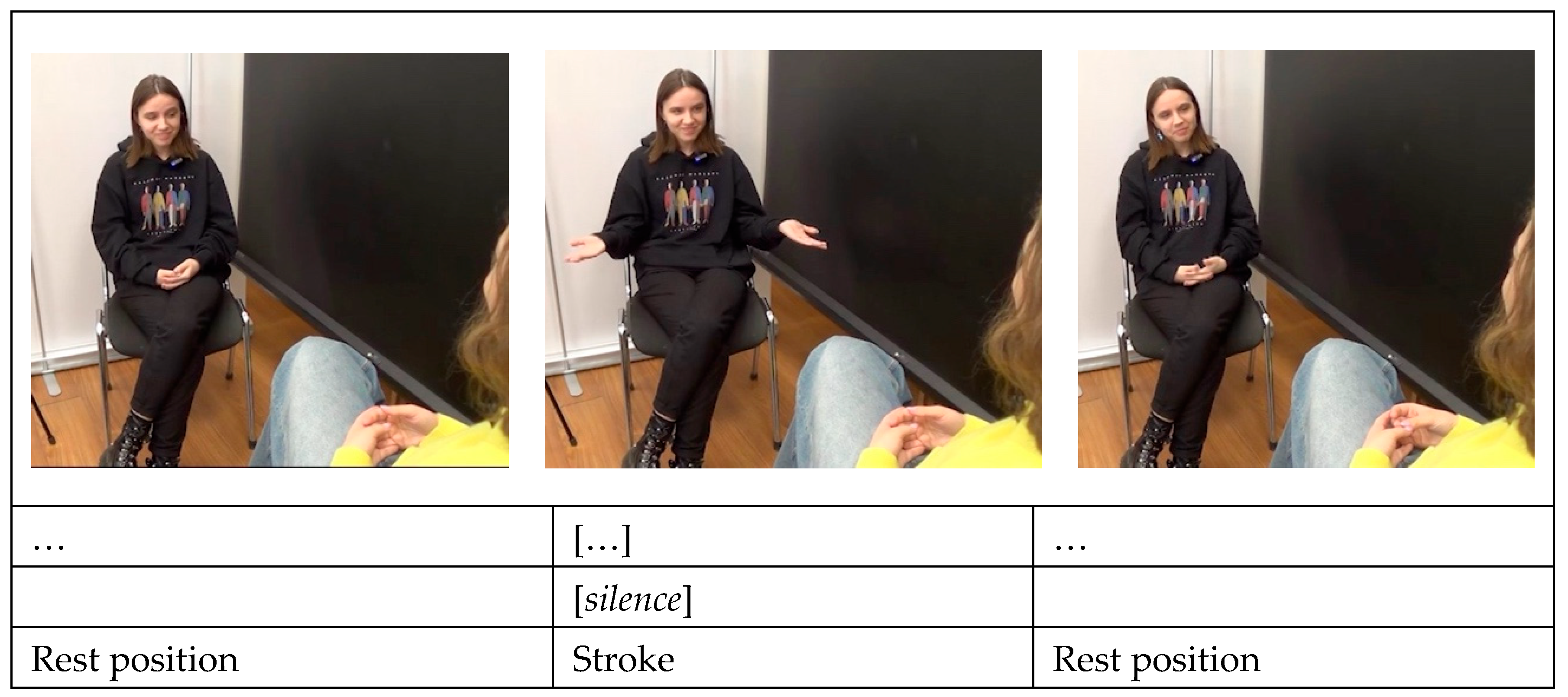

However, in many cases, Offering gestures entailed much less effort, involving a simple turnout of the hand and lower arm. This is illustrated in the example in

Figure 7.

The speaker simply summarizes her view on what they have been saying about the level to which AI has been developed, turning her hand out towards her interlocutor. It can be seen as a kind of concession—that this is where we are now in terms of the development of technology (and not further along). The maximal turnout of this Offering gesture does not involve a fully open hand with all fingers stretched out straight, but several fingers remain slightly curled, more relaxed rather than tense. At its furthest extent, the palm is only diagonally upward. The three dots (...) in the transcription of the speech indicate a long pause.

A more minimally effortful version of Offering can be seen in

Figure 8 on the part of the speaker who is facing the camera. Though her two hands are clasped, the position still affords movement of her fingers, which she does with her left hand. As she offers her word of caution, that there’s something “slippery” or tricky in the situation being discussed, she extends her fingers out into the interactional space and then brings them back to the clasped position. No rotation outward of the lower arm and hand is involved. It is a minimally salient kind of gesture; the finger lift discussed in

Cienki (

2021) is an even more minimal version of Offering as finger extension. The context before the example in

Figure 8 is that they have been discussing who is responsible if some AI makes a decision that harms people or causes damage (like a power blackout). The speaker on the right (with her back to the camera) concludes that those who programmed the AI are responsible. But the speaker on the left interjects that there is a “slippery” issue to be considered, and points out that the AI could develop itself in new directions that the original programmers had not anticipated. The small Offering gesture is the initiation of her turn in which she presents a new perspective.

Supporting the argument in

Cienki (

2021), we find that speakers offer their points with varying degrees of effort, ranging from simple finger extensions, to rotation outward of the lower arm and hand, to full PUOHs. Indeed, the findings once again bring up the suggestion raised in

Cienki (

2021, p. 28) that “it is perhaps the hand turn-out that should be seen as constituting the prototype of the gestures for presenting a point, rather than the PUOH”.

As noted earlier, Side-Offering serves the function of mentioning a point that is tangential by being either not directly related to the current interactional space of the interlocutors or not directly connected to the discourse up to that point. In the example in

Figure 9, the speaker notes that if we reach the point that robots do everything for people, people may no longer remember how the robot (the machine) itself even works. The idea is presented as an additional point, showing how far the situation might go. In the given full realization of Side-Offering, the speaker not only extends her fingers straight out, but also turns her hand completely palm up, and also rotates it outward at the elbow away from her torso, into the peripheral side space.

However, Side-Offering need not result in a PUOH, and need not be located as far out from the body. In the middle frame of the example in

Figure 10, the speaker moves his open hand downward with his palm facing laterally (facing the central gesture space). His thumb is also slightly turned in, reflecting a hand shape that is not completely tense and flat. His left hand, which is not raised very high in the first frame, moves downward via a small extension from his left elbow. His left hand then becomes the target that his right hand moves to in a stroke after that, which is not the focus of interest here. The context is that the dyad is discussing who may be considered responsible if some AI makes a mistake. The speaker shown in this example is laying out the different possible parties who might be to blame. The first he names here is the creator (or author) of the materials that were used to train the model. His gesture offers this option off to his left side.

Side-Offering can also be manifested in a much less effortful way. In

Figure 11, the gesture with the right hand is produced contralaterally, but since the speaker’s starting rest position is on her left side, the resultant gesture is small. The gesture stroke of her right hand just involves finger extension and a small turning out of the hand, such that the movement from the rest position is so small that the palm is still facing herself. There is also a small extension of the fingers of her left hand; as a result, both her left thumb and the fingers of her right hand are directed off to her left side.

Prior to this example the pair had been discussing how reliance on technical “gadgets” may be reducing people’s ability to memorize things. The speaker facing the camera makes the point (in the example in the figure) that, by contrast, their older colleagues who have not relied on such gadgets still have fine memories. The Side-Offering gesture emphasizes which group she is talking about by offering them as a topic to her side, a move which could help differentiate them from her interlocutor (who is not one of those older colleagues being mentioned), as the gesture is not directed into the interactional space directly between them.

Gestures of Spreading hands differ in both pattern of motion and function from Offering gestures. Let us begin with an example showing more effortful production of Spreading of one’s hands. As shown in

Figure 12, this case involves the two hands separating laterally and symmetrically from a central rest position, ending the stroke with both hands stretched flat, forearms having rotated externally resulting in the palms facing vertically up, and each palm in a peripheral lateral location resulting from abduction (movement outward) from the elbows. Prior to the example in

Figure 12, the participant on the left has been expressing the view that real interaction and conversation takes place with living people, not with machines, and that only interpersonal contact, even through written correspondence, can involve emotions. The speaker on the right agrees and notes that someone could fall in love with an AI system and lose track of the fact that it is not a living being (as she says, “

A evo na samom dele net” [‘But in fact, it doesn’t exist’]). As she says that, her interlocutor on the left smiles and nods her head, and in the silence that follows (marked with three dots), she responds without speaking by producing a large Spreading gesture shown in the figure. In this context, her gesture appears to show her agreement with what her interlocutor said, and to highlight that there is nothing there; an AI is a virtual being.

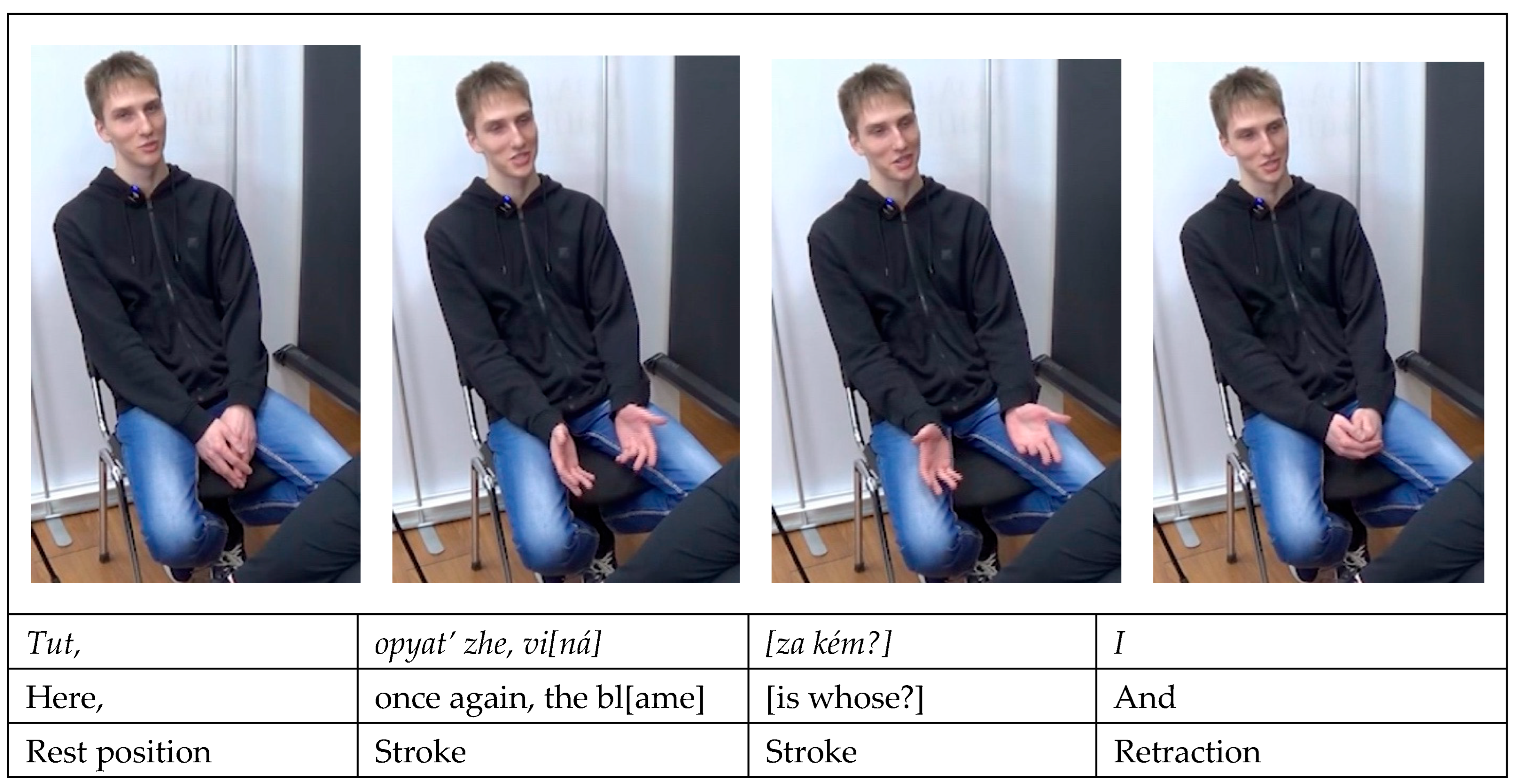

However, the Spreading need not be so extreme; one’s two hands simply turning outward symmetrically might also constitute Spreading on a small scale, serving a similar function of showing the absence of knowledge or accountability. Before the example in

Figure 13, the two people were discussing who is responsible if AI does something that is unethical, such as, for example, generating keys to break into Microsoft Windows. The Spreading gesture of the speaker shown can be seen as relating to the lack of responsibility in that case, as he is posing the hypothetical question as to who is to blame for such an unethical act (that is: the answer is not clear). The first part of the stroke (shown in the second frame), followed by a micropause, shows how a Spreading gesture can simply involve the hands partially open, one palm (the left, in this case) diagonally up, and the other palm facing laterally. Rather than involving a PUOH, the relevant feature is the symmetrical lateral turn-out of the two hands, from clasped to separated.

Even smaller versions of Spreading are possible, particularly when the speaker is seated, hands on their lap. This can be seen in

Figure 14, in which the speaker’s hands open up just to a position with palms facing each other. The pair was discussing what will happen as AI is brought into outer space. The speaker on the right mentions a scenario in which we have left our planet in danger and so we fly on to the next one. Her interlocutor, shown here, says, “

Nu, …” [‘Well, …’] and laughs, suggesting that we might be left in such a position. The Spreading gesture once again potentially serves to express a combination of helplessness and not knowing what will happen.

We see that what is the same across the Spreading gestures is the symmetrical lateral extension at the wrists and/or rotation outward of the lower arms and hands from a central vertical axis. More effortful versions involving further rotation outwards, leading to a PUOH, and even more extensively: abduction of the upper arms at the shoulder joint, moving the hand into a more peripheral lateral space. As noted in

Section 5, such a movement opens up the space to varying degrees in front of oneself and admits access to oneself, which can show that one is not holding or hiding anything. In an abstract sense, pragmatically, this action can indicate notions such as showing that one is allowing for a possibility, lacks accountability for something, or that one does not have an idea or an anwer to a question.

8. Discussion and Conclusions

The research on PUOHs across languages has pointed out the variety of functions that such gestures can have. However, the singular label for them—be it PUOH or palm-up supine—has made them appear to be one phenomenon. This has led to the puzzle as to how this one form could have functions as diverse as presentation and expressing an epistemic stance. While

Cooperrider et al. (

2018) pinpoint a distinction in functions based on the location in which the gestures are produced, we are left with another puzzle as to why a number of other gesture tokens in conversation that do not have the same handshapes and/or palm orientations also serve those functions.

Action schemas have been proposed here as a possible solution for explaining not only how there can be variants that do not involve a palm turned upward or a flat open hand, but also how such variants can form a set with instantiations that do have the PUOH form to fulfill certain pragmatic functions with speech. To explain the idea of any given action schema as having manifestations that differ in their degree of fullness of expression, it might help to use an organic analogy from the field of botany, if we compare an action schema to a fern frond. A fern frond is most easily recognizable when it is fully unfurled, maximally extended. However, a young, coiled fern frond is nevertheless a fern frond; it is the same leaf as the large open frond, but in a more compact form. The leaflets comprising it are not yet open and facing upward (making for a “leaflet-up, open frond”), but one familiar with ferns can recognize a frond as such in any of its degrees of unfurling. The function of the frond is also essentially the same from early to full unfurling—that of providing energy to the rest of the plant through photosynthesis in the cells of its leaflets—even if the intensity of the function varies according to the degree of extension of the frond. Similarly, Offering and Spreading hand gestures can be ‘unfurled’ to different degrees in their different manifestations, and tokens of each type still perform the same general function of the type, even if with different degrees of intensity.

In addition, the focus in much existing research on the single palm orientation (palm up) and handshape (open hand) obscures the fact that the two main categories, called here Offering and Spreading, differ in terms of how the gesture strokes originate. Offering gestures usually begin with an extension of the fingers of one hand and possibly an outward rotation of the lower arm, and possibly an extension at the wrist, with movement upward and/or forward—or laterally outward for Side-Offering. Spreading gestures, however, involve two hands moving outward from a central vertical axis with a rotation outward of both lower arms, to varying degrees of extension.

Boutet’s kinesiological system thus highlights the importance of analyzing gestures not only in terms of how they look, but also (or even mainly) in terms of how they are physically produced. The four form parameters that are traditionally used in the study of manual gestures describe the hand shape, palm orientation, location in gesture space, and movement direction (e.g.,

Bressem et al., 2013;

Mittelberg, 2007). As useful as these are, they provide categories that are not only (for the most part) static in terms of what they describe, but which also take an observer’s (3rd person) perspective on the gestures, as an observer sees them in a video. Kinesiological factors, however, concern what kinds of actions the muscles are taking on the joints (e.g., extension, flexion, rotation, etc.), what body parts are moving, and how. It describes a dynamic system, and does so from the gesturer’s (1st person) perspective (

Boutet & Cienki, 2024).

In addition, much gesture research since the 1990s has focused on how the hands

represent forms and scenes that the speaker is talking about. This is partly a factor of the typology for gesture analysis that McNeill launched with his 1992 book, focused on having participants in psychology labs retell a cartoon or film that they viewed via a monologic narrative. The gesture typology he used for this focused on four categories: iconics, metaphorics, deictics, and beats; the four form parameters, mentioned above, became the customary way of describing such gestures. However, that typology does not explicitly include pragmatic functions of gestures, except for how gestures can indicate emphasis with beats. Other gesture forms used with pragmatic functions presumably fall into other categories in his system (e.g., PUOHs, cyclic, and some other gestures perhaps being considered metaphoric). But if we look at everyday conversations, only a small part of them entail description of physical motion events. In fact, one study (

Nicoladis et al., 2024) that specifically examined the use of representational versus non-representational gestures found no correlation between the frequencies of their use when participants retold a cartoon they had watched versus when they took part in a conversation. Another study (

Graziano & Gullberg, 2024) found that even in narrative retellings, where one would expcet more representational gestures, Italian speakers used many pragmatic gestures, especially palm up gestures (constituting half of the gestures they produced). Much of what people do in naturally occurring conversations is exchanging viewpoints and opinions, something which involves stance-taking (

Biber & Finegan, 1989;

Biber et al., 1999, ch. 12;

Chindamo et al., 2012;

Du Bois, 2007). In such contexts, gestures engage pragmatic functions. This means that the kinds of gestures people use most would likely be recurrent gestures with such functions, as characterized by

Bressem and Müller (

2014a),

Ladewig (

2024),

Streeck (

2009), and others. Here we can also note the development of the use of palm up gestures with pragmatic functions beginning even in childhood.

Beaupoil-Hourdel and Morgenstern (

2021) point out the change from initial uses of palm-up gestures which just correlate with the physical absence of an object the child is looking for (at as young as 1 year 4 months old in a British child studied) to later epistemic uses (related to not knowing).

Graziano (

2014) illustrates how the pragmatic uses of palm-up gestures comes into play in particular as children develop the skill of planning and structuring their discourse (noting this becoming apparent at around age 6 in the Italian children she studied).

An additional point is that whereas depictive gestures involve more effortful handshapes and specific use of space in order to produce their iconically rich representations, we observe that recurrent gestures with pragmatic functions may often be produced in more relaxed ways; their function involves expressing something about the speaker’s stance or attitude, not illustration of a specific form. The present study proposes that action schemas, rather than static parameters, are a more informative means of analysis of this default repertoire of gestures (recurrent gestures) that speakers use in everyday conversation.

Future work will involve more detailed analysis of other action schemas. A number of recurrent gestures identified among German speakers (

Bressem & Müller, 2014a), for example, have already been described in terms of schematic action patterns, for example: the gesture involving a cyclic motion of the hand, a gesture used as if gripping something precisely with the fingertips, and several gestures based on movements of brushing or sweeping small objects away. See also

Calbris (

2003) on the flat open hand(s), palm(s) facing laterally, moving with a downward or outward motion in the plane of the flat hand as embodying a cutting schema. Gestures enacting these schematic actions were also found in the Russian data, as well as some types not as well known from discussions of gesture use in other cultures. These will be studied not only for their range of instantiations, but also in relation to verbal expressions of stance-taking, as a means of ascertaining the pragmatic functions of such gestures.