A Sequence-to-Sequence Transformer-Based Approach for Turbine Blade Profile Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

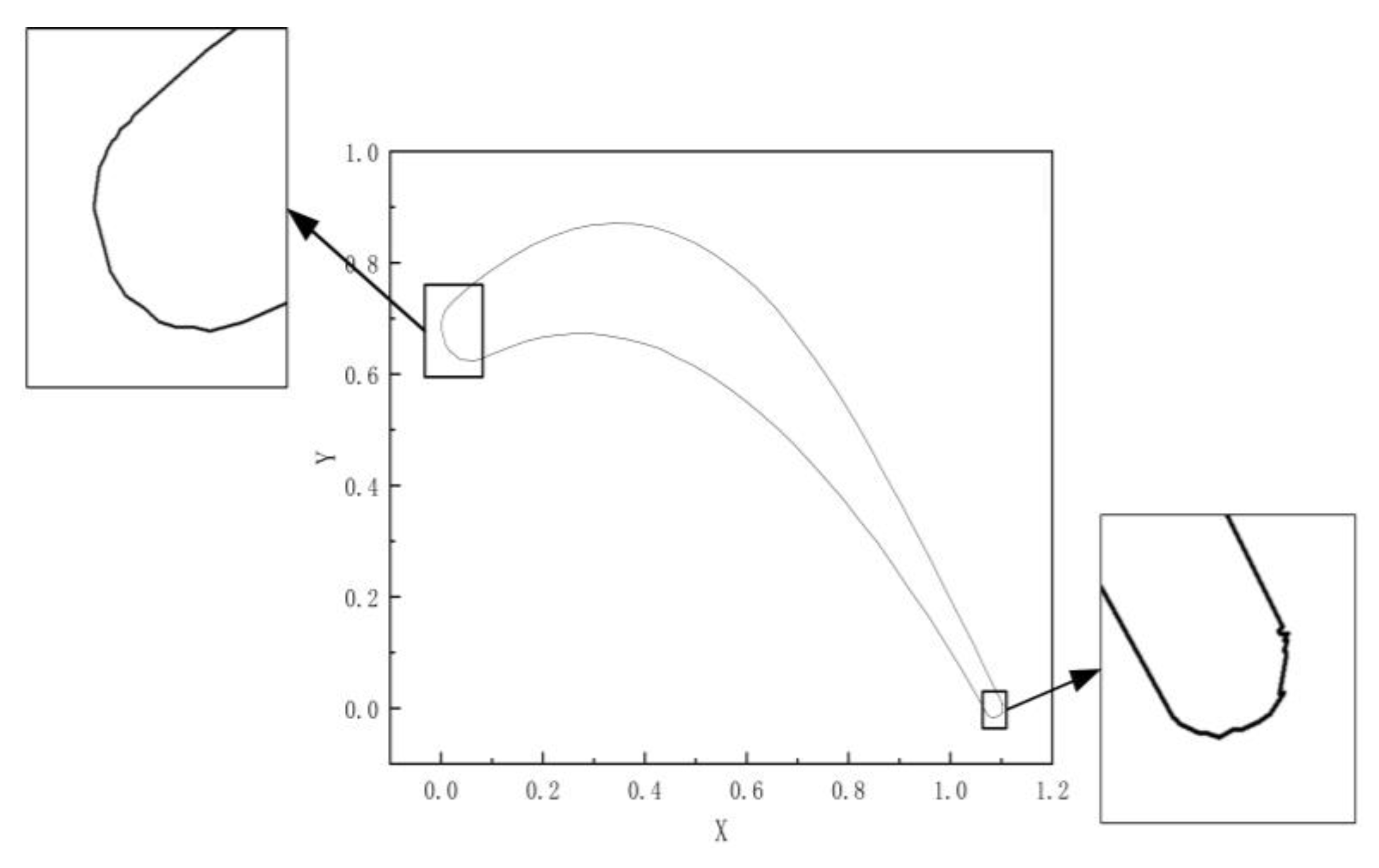

2. Research Object and Dataset Composition

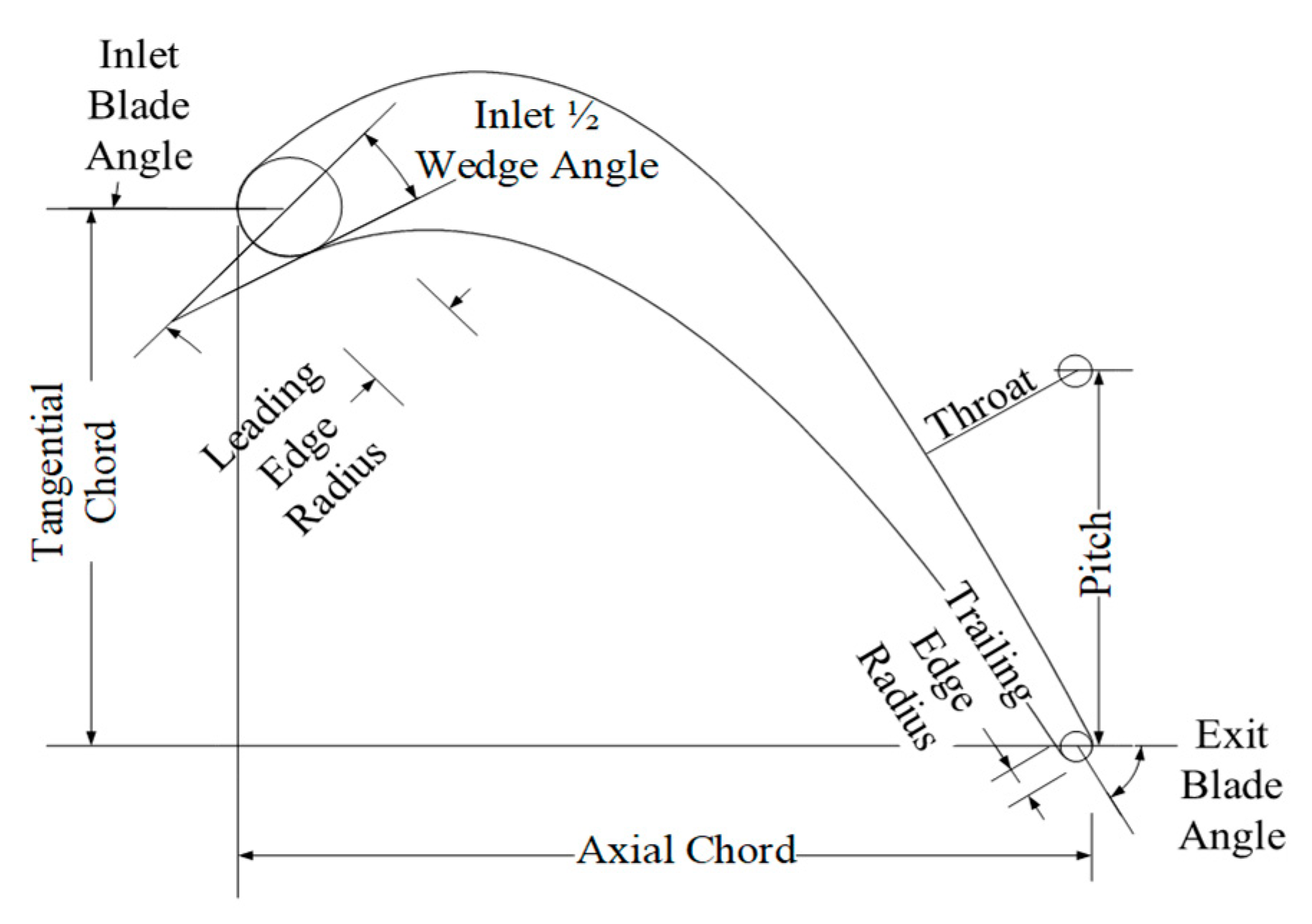

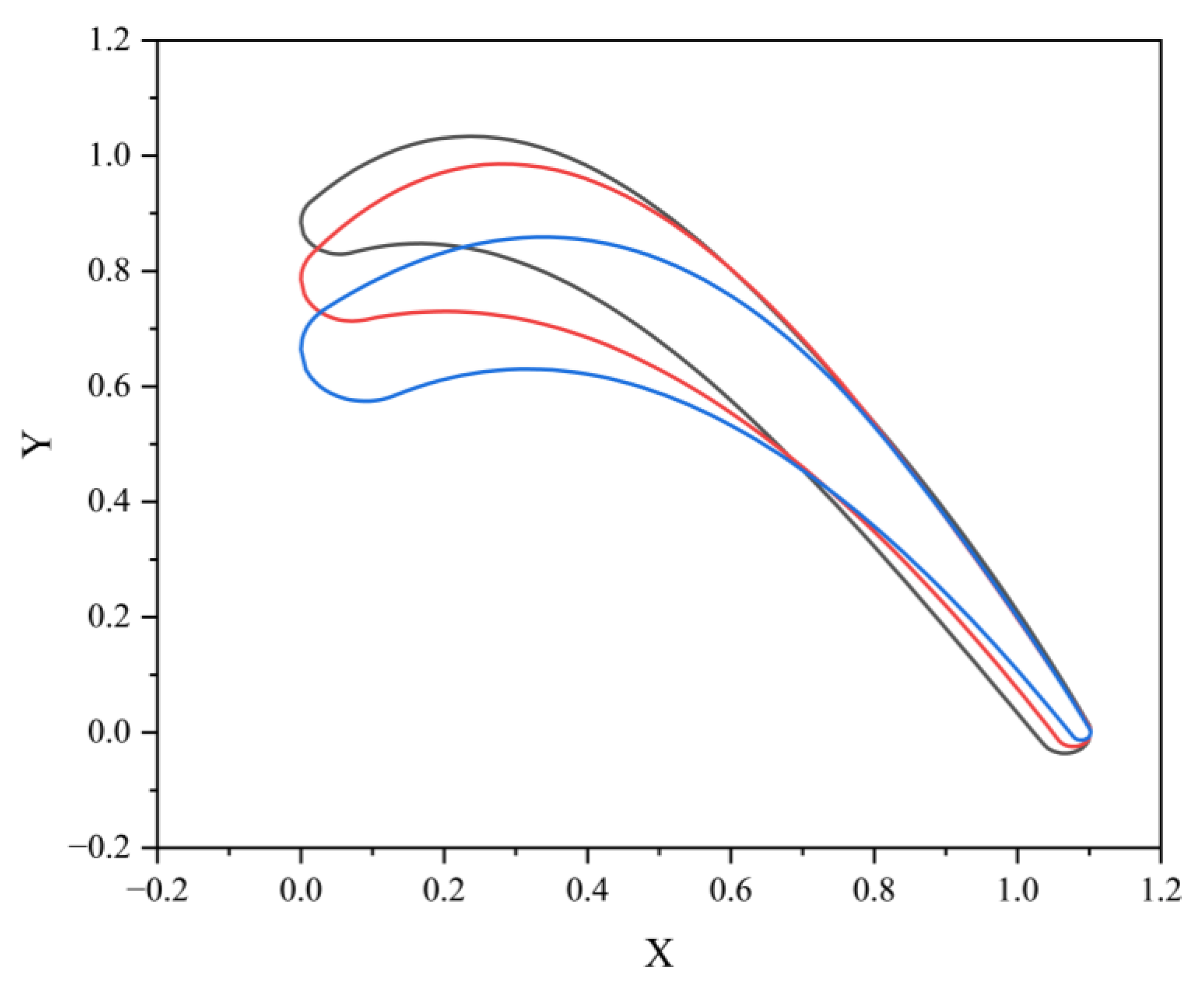

2.1. Data Generation and Processing

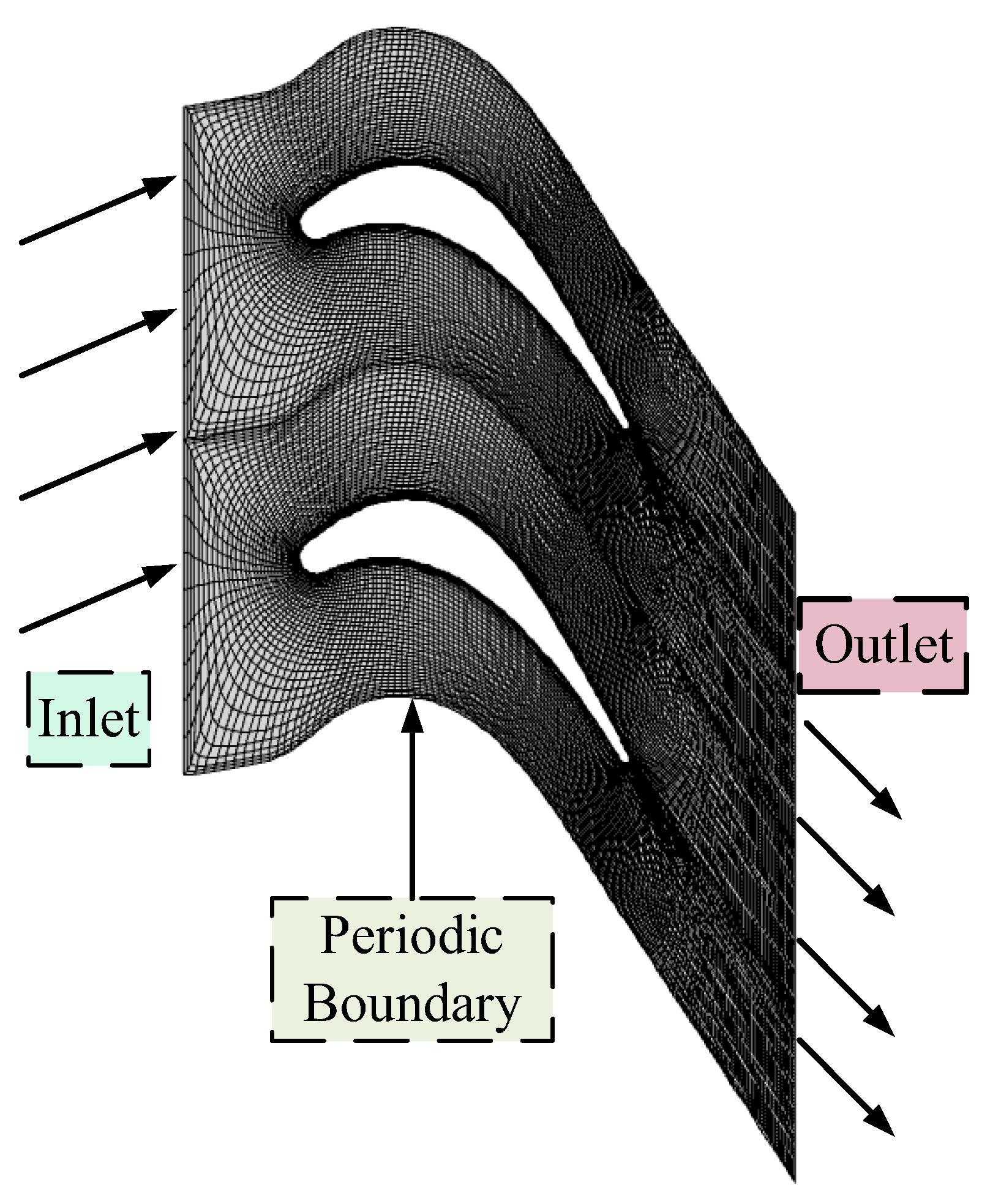

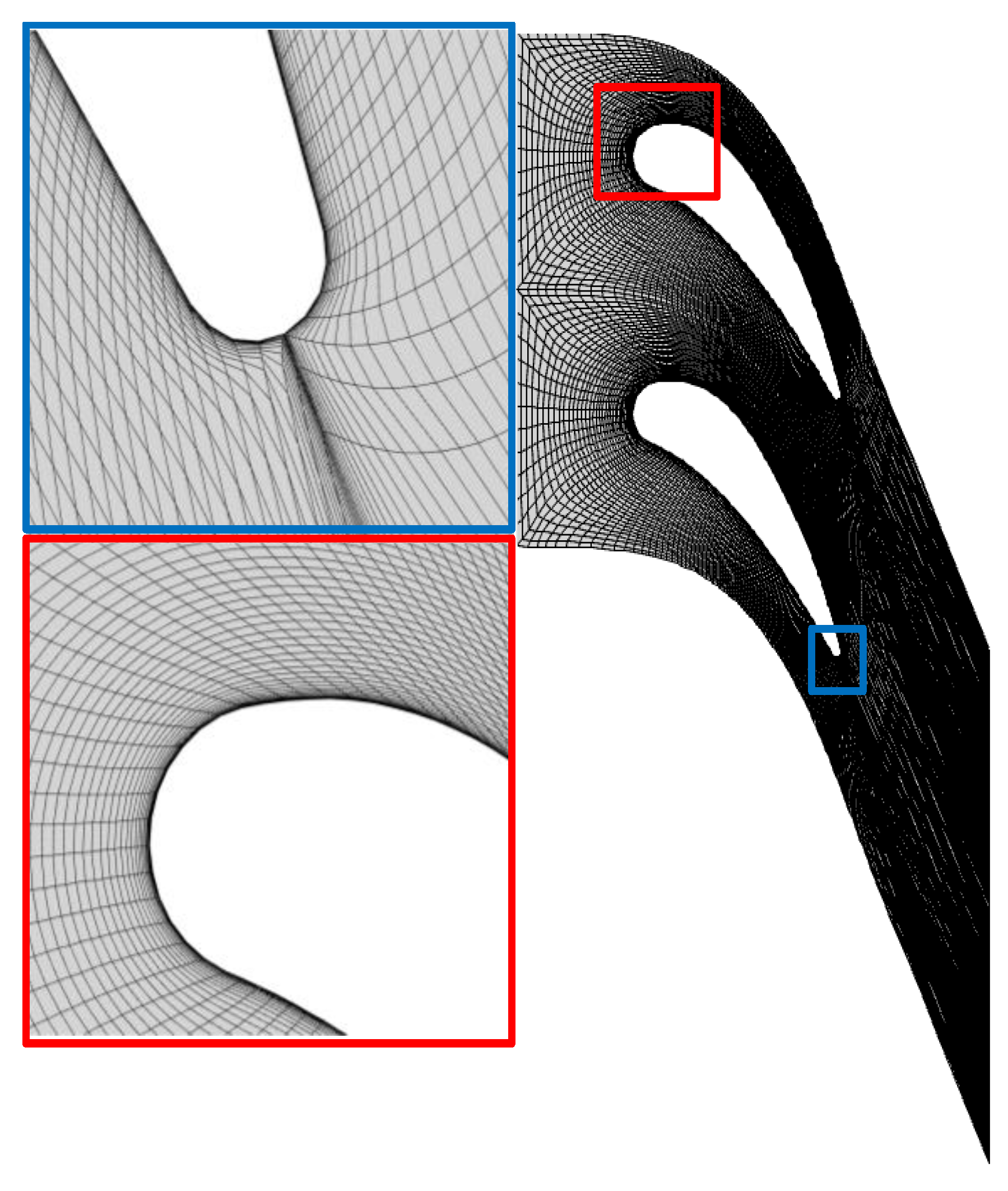

2.2. Mesh Generation and Flow Field Solution

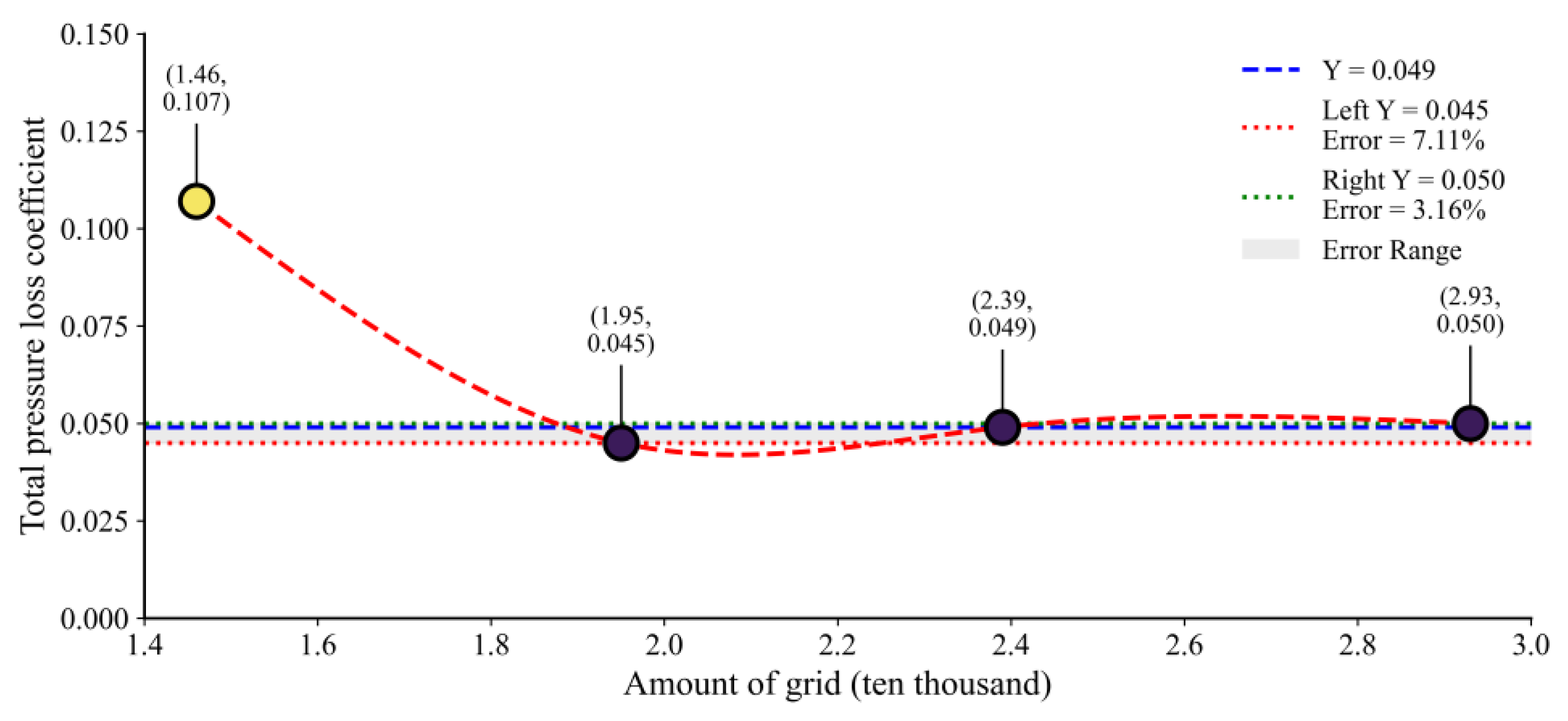

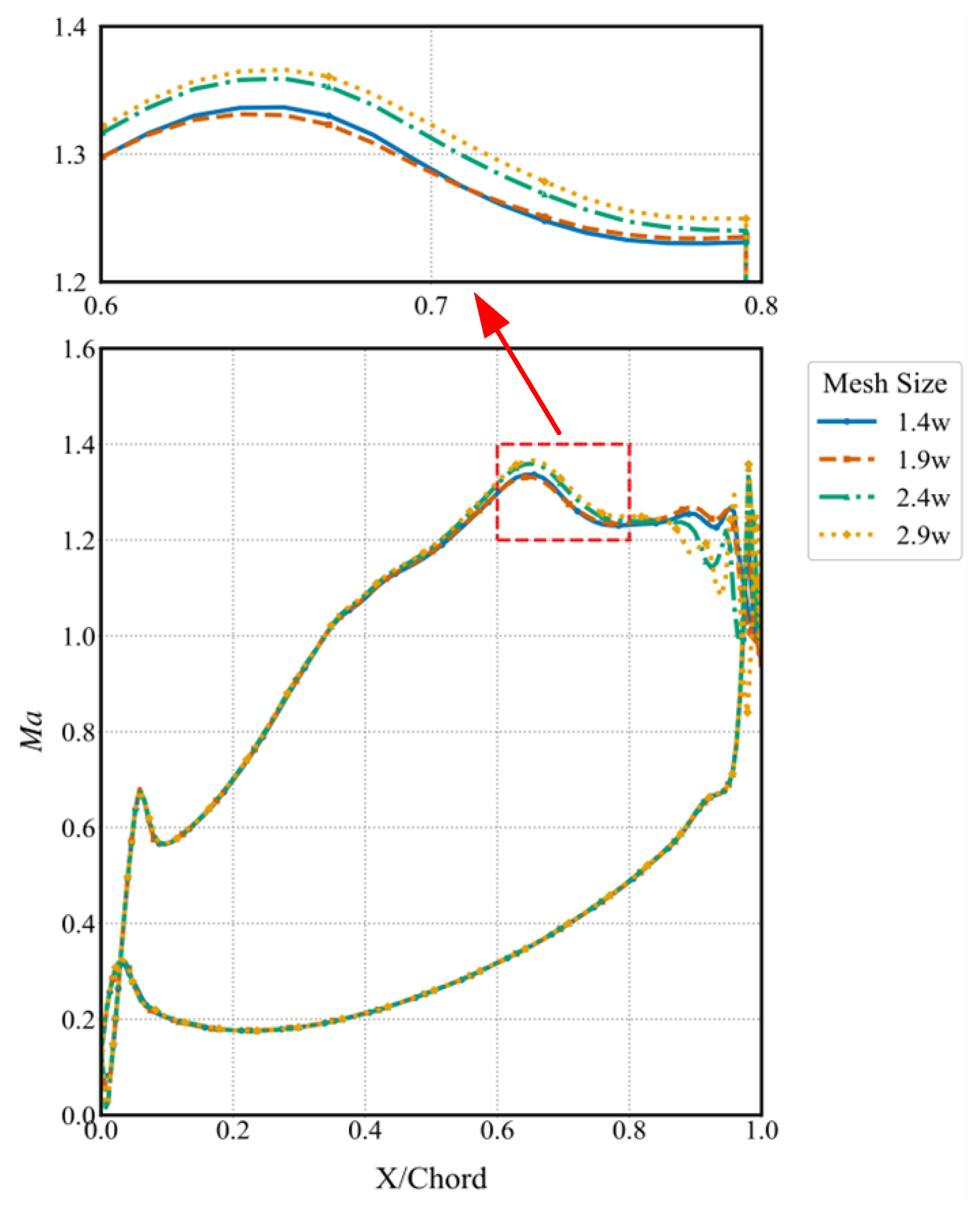

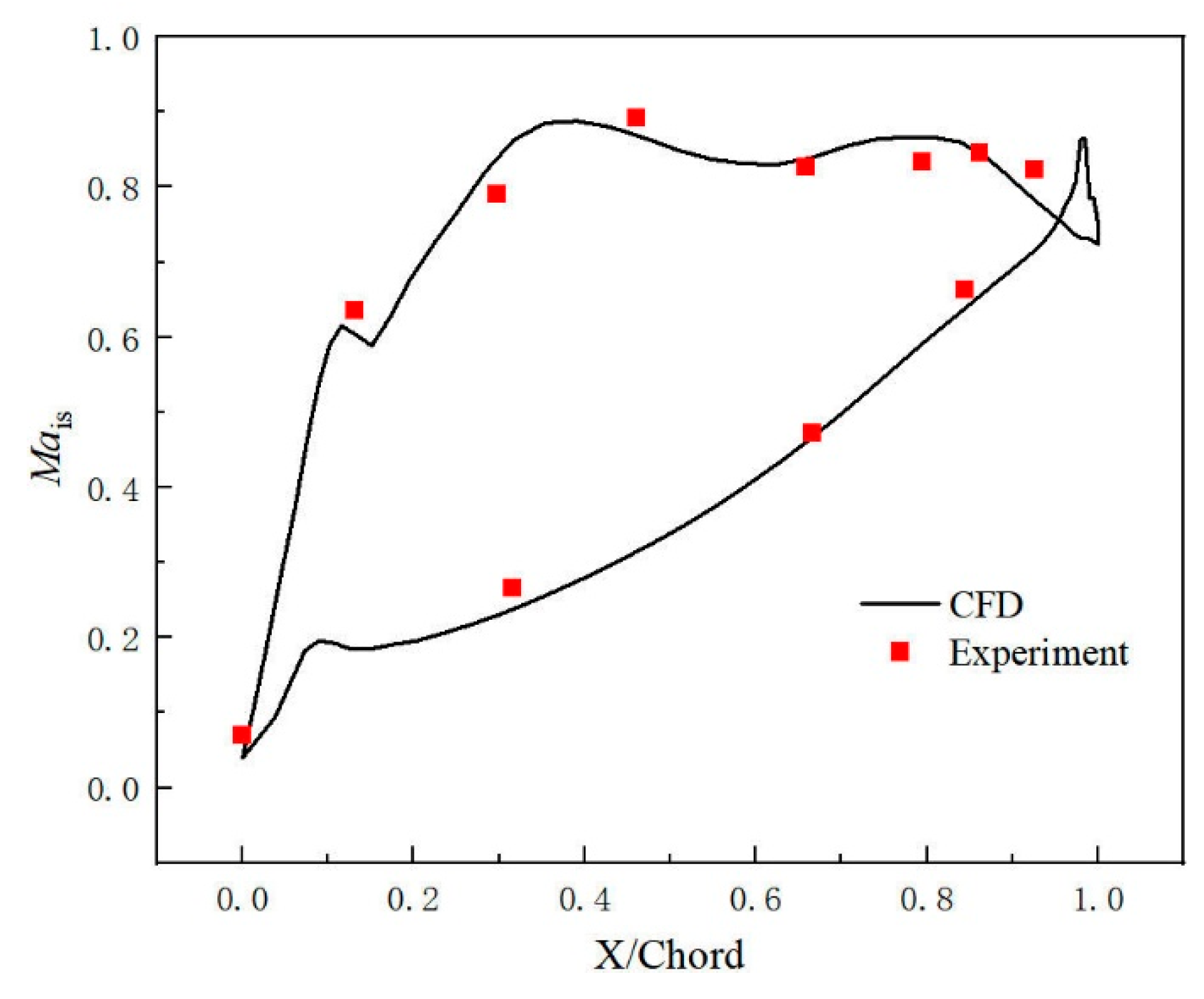

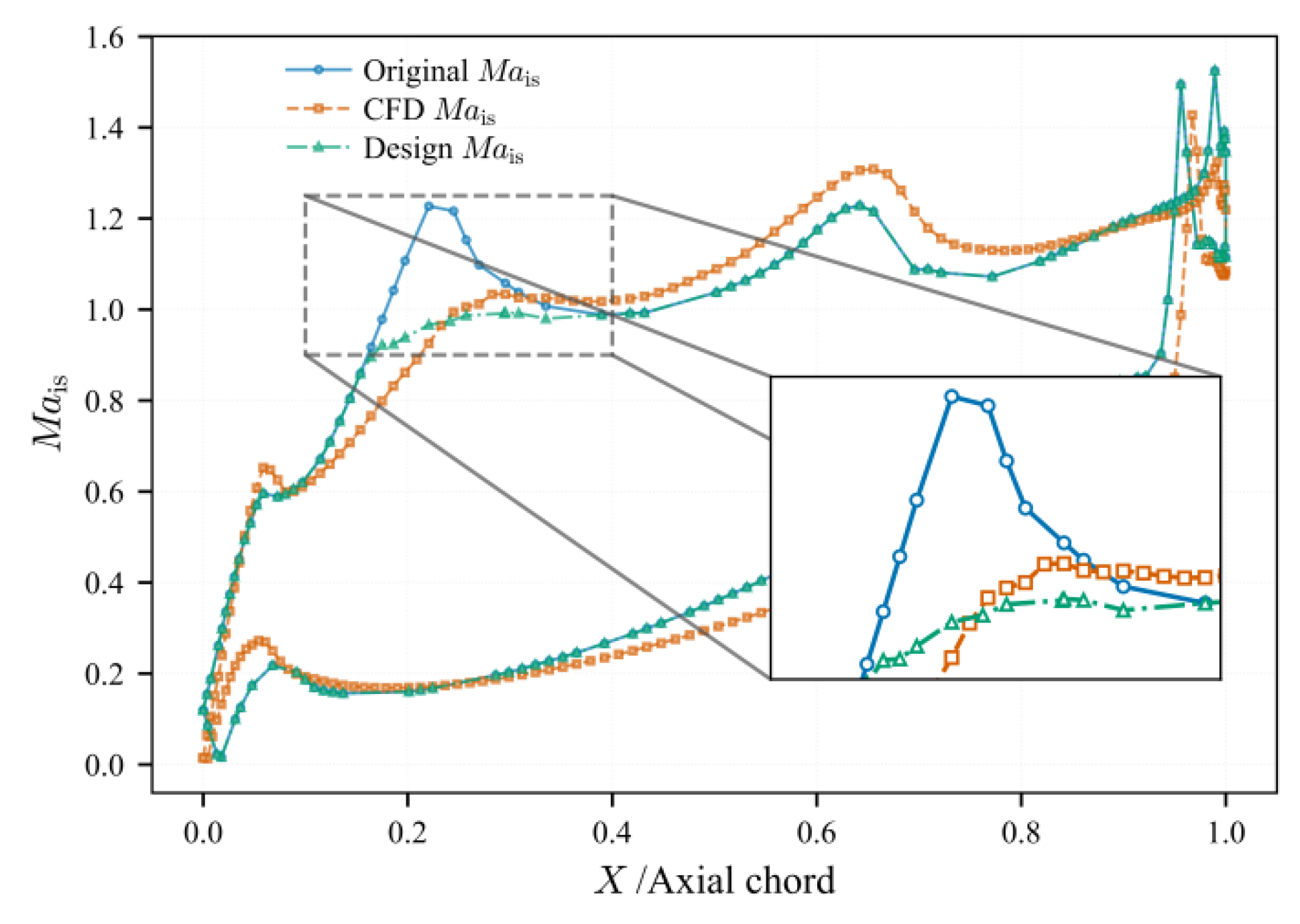

2.3. Mesh Independence Verification and Computational Fluid Dynamics Program Validation

2.4. Dataset Construction and Splitting

3. Theoretical Methods

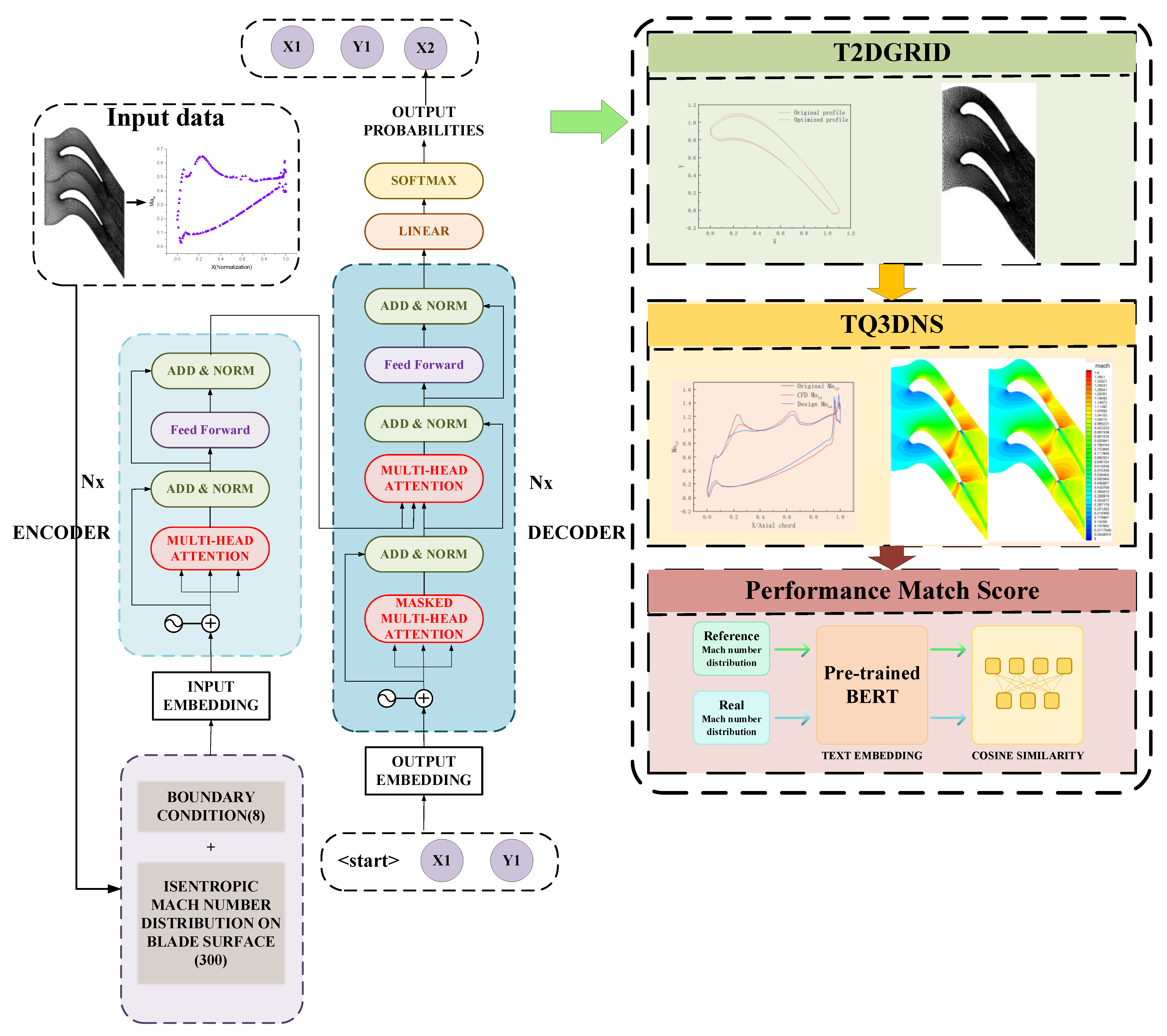

3.1. Turbine Blade Optimization Framework Based on Sequence-to-Sequence Transformer Model

3.2. Transformer Principles

3.2.1. Attention Mechanism

3.2.2. Position Encoding

3.2.3. Feedforward Neural Network

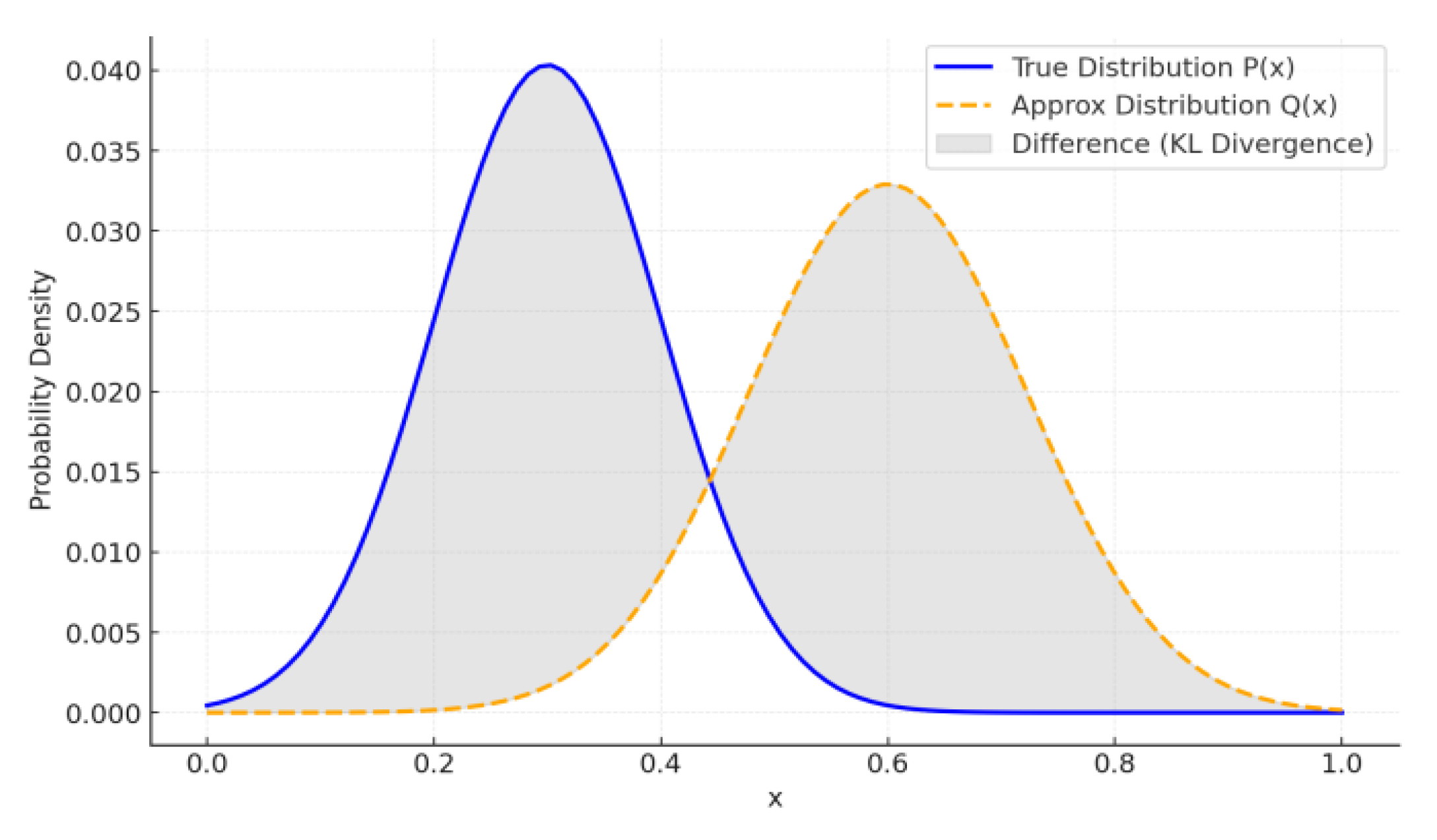

3.2.4. KL Divergence Loss Function

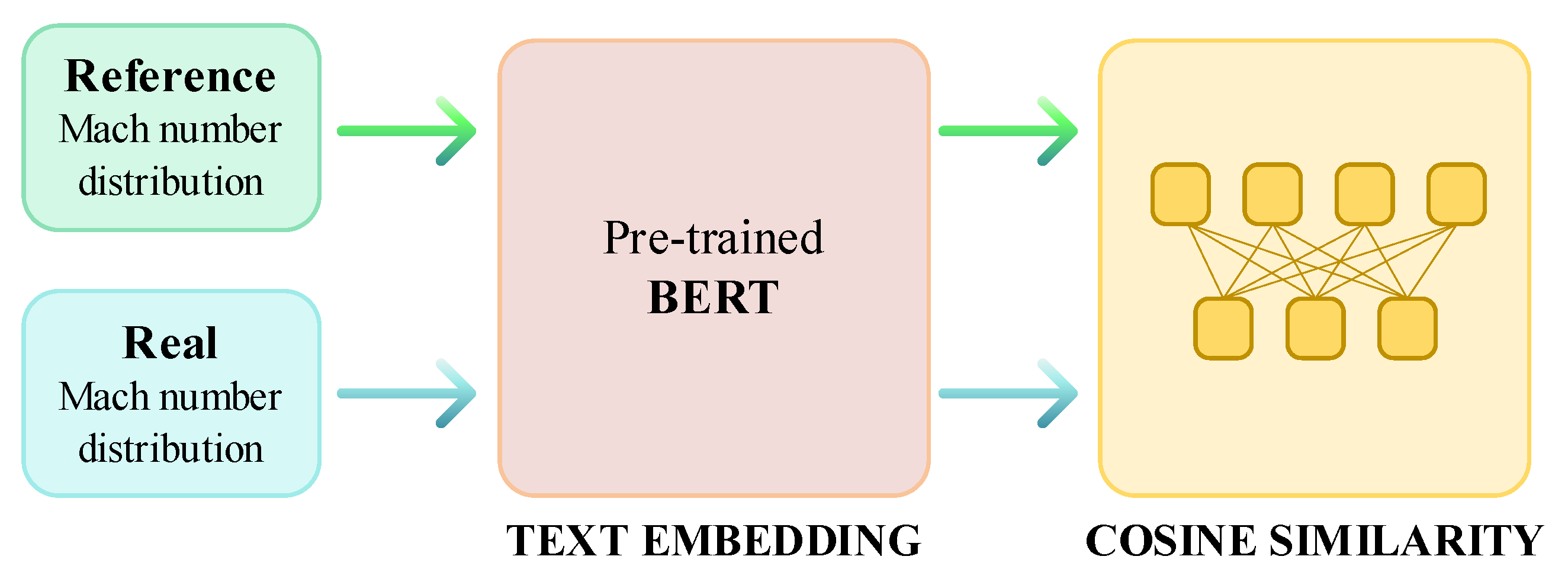

3.3. Performance Matching Metric

4. Transformer Model Design

5. Analysis of Blade Profile Optimization Results

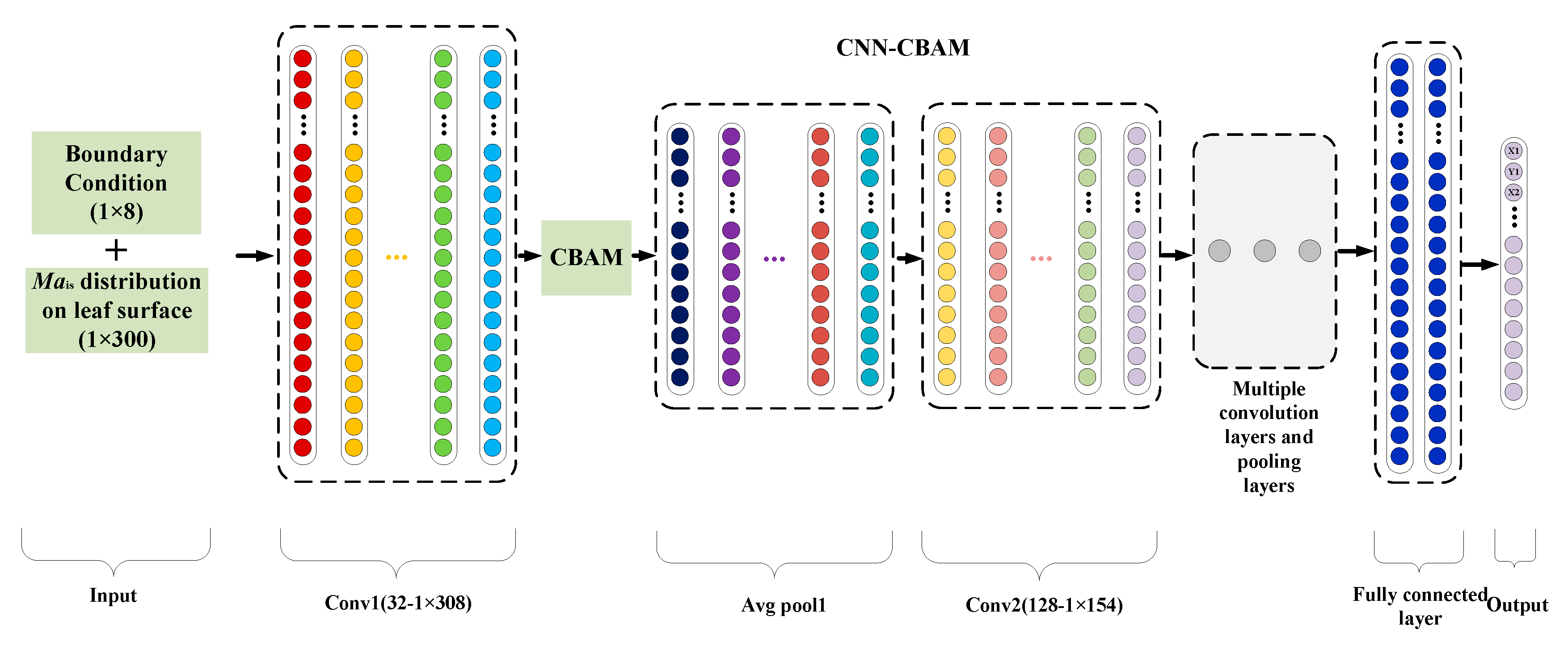

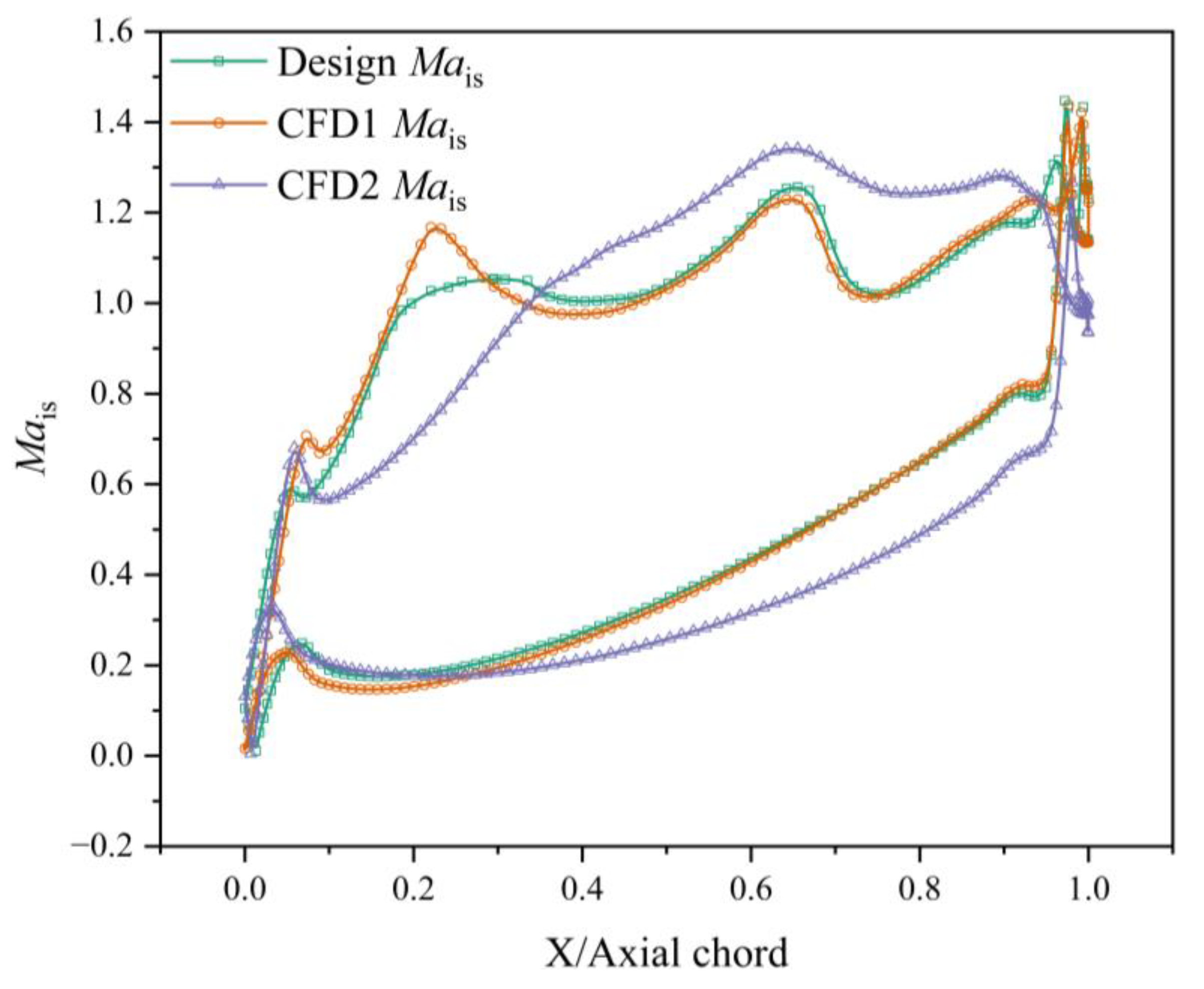

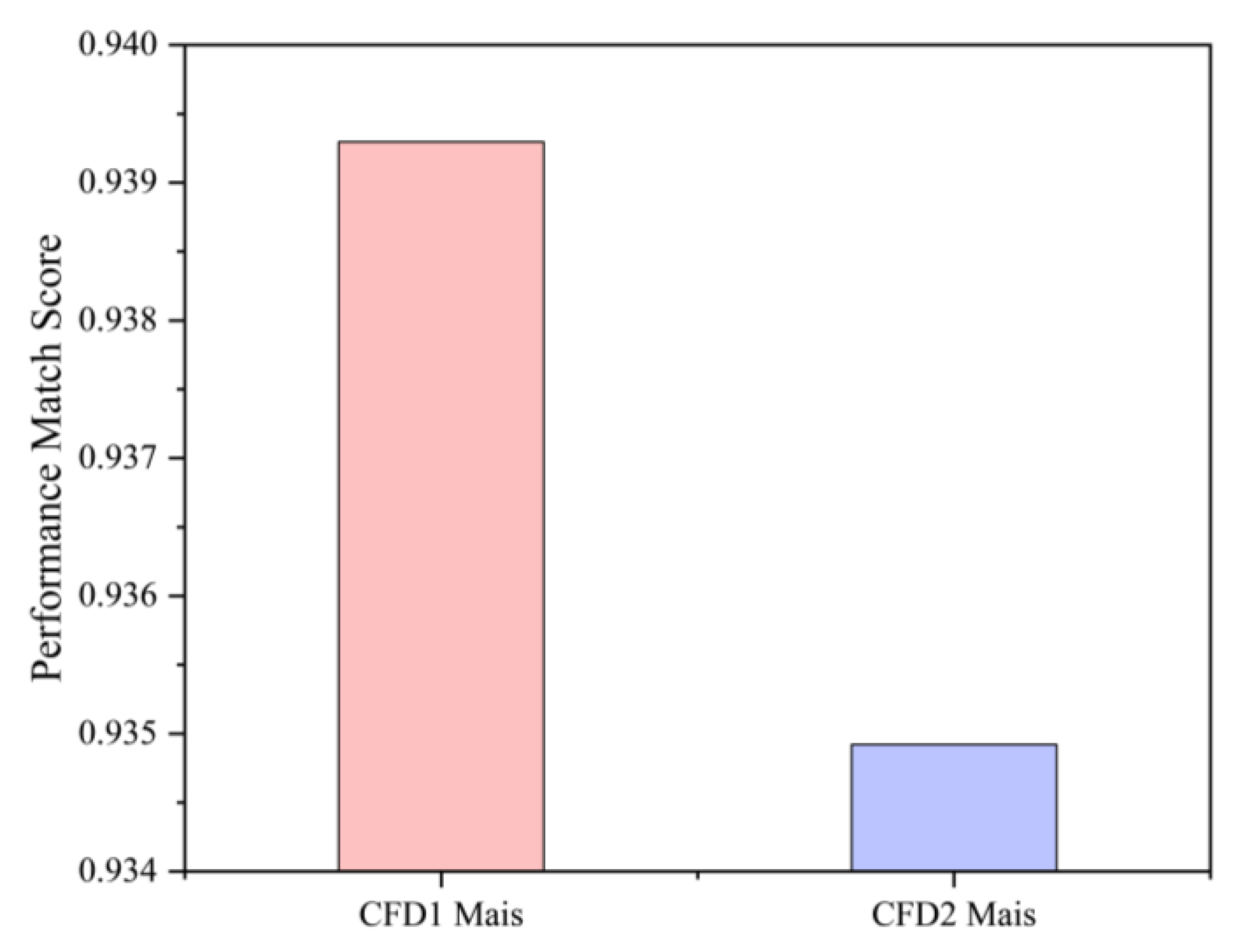

5.1. Evaluation of CNN-CBAM Model Prediction Performance

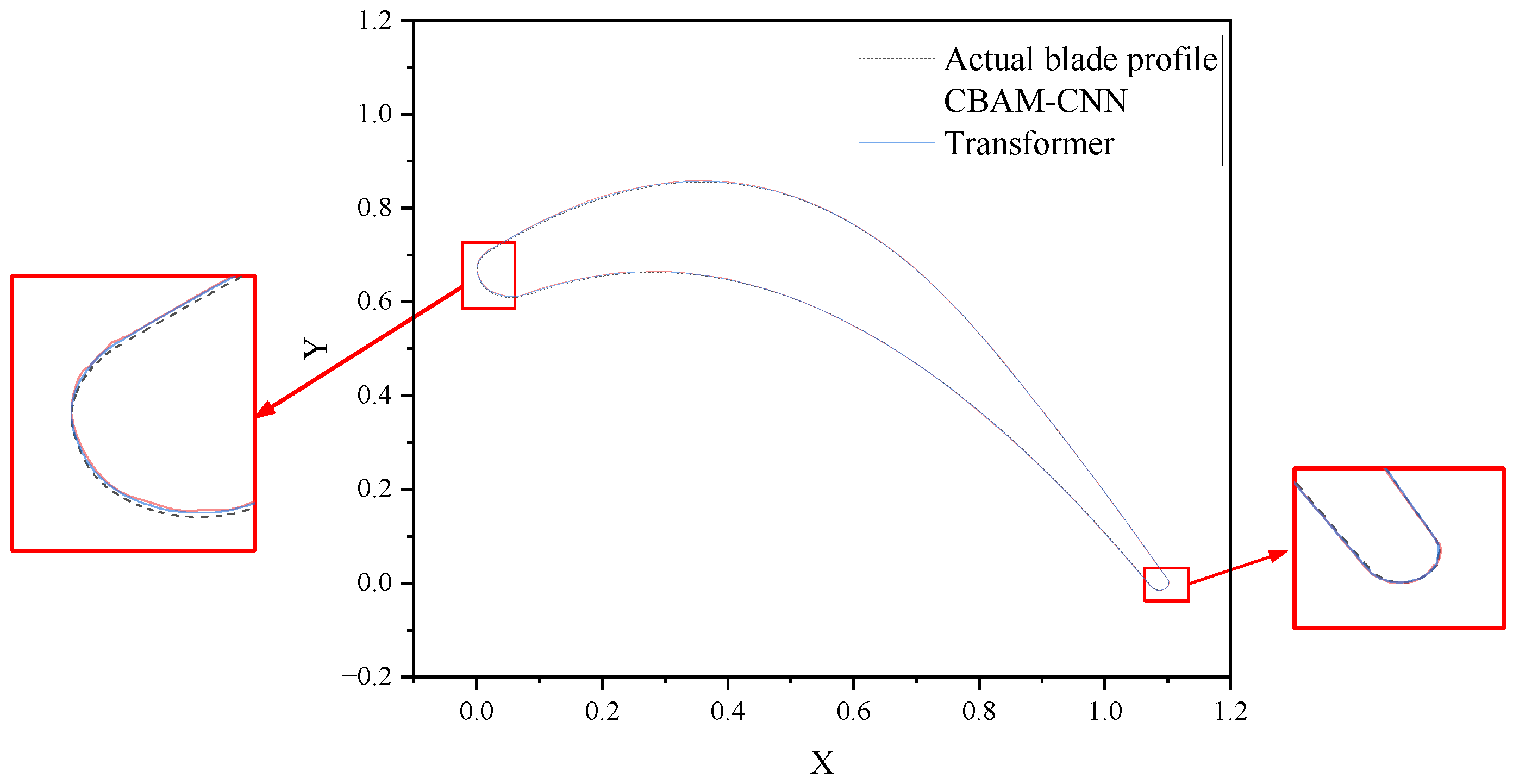

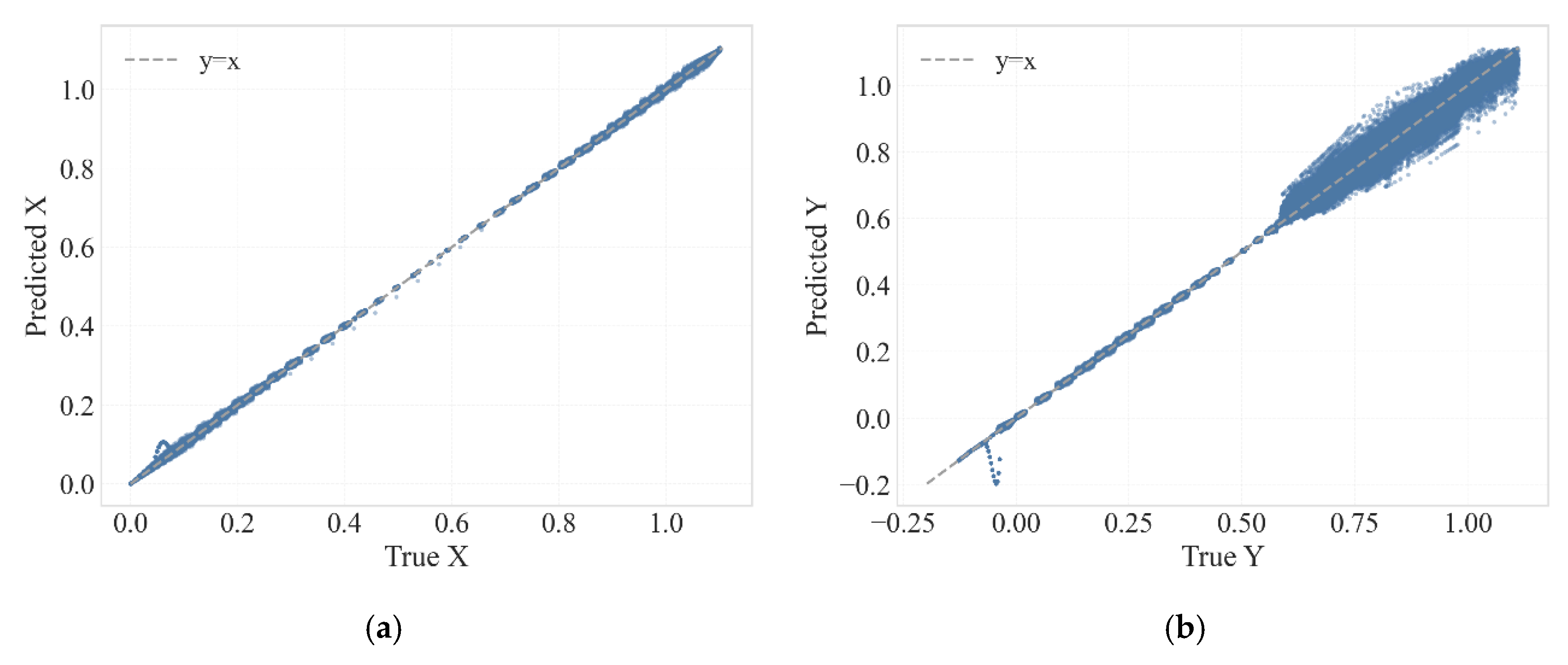

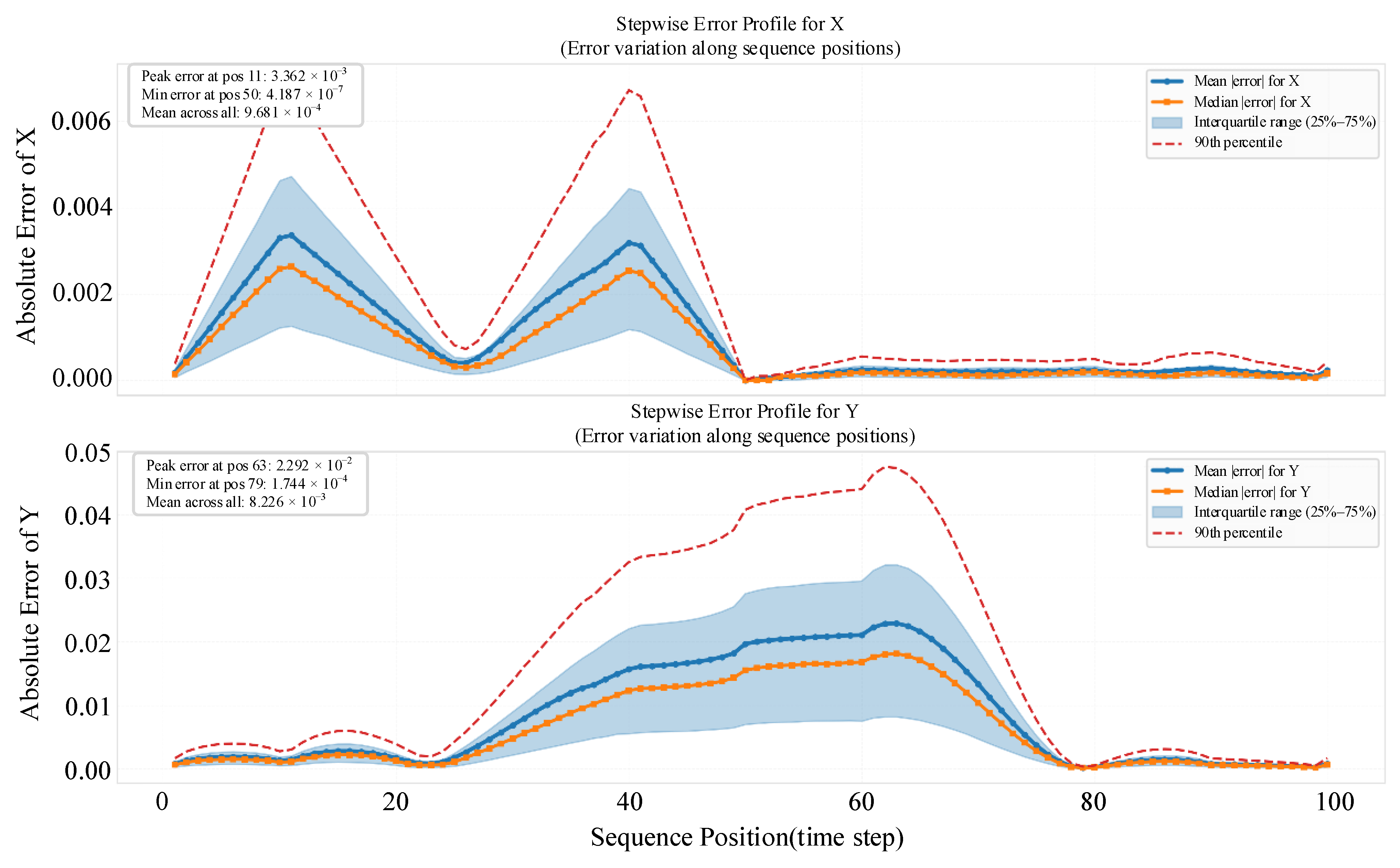

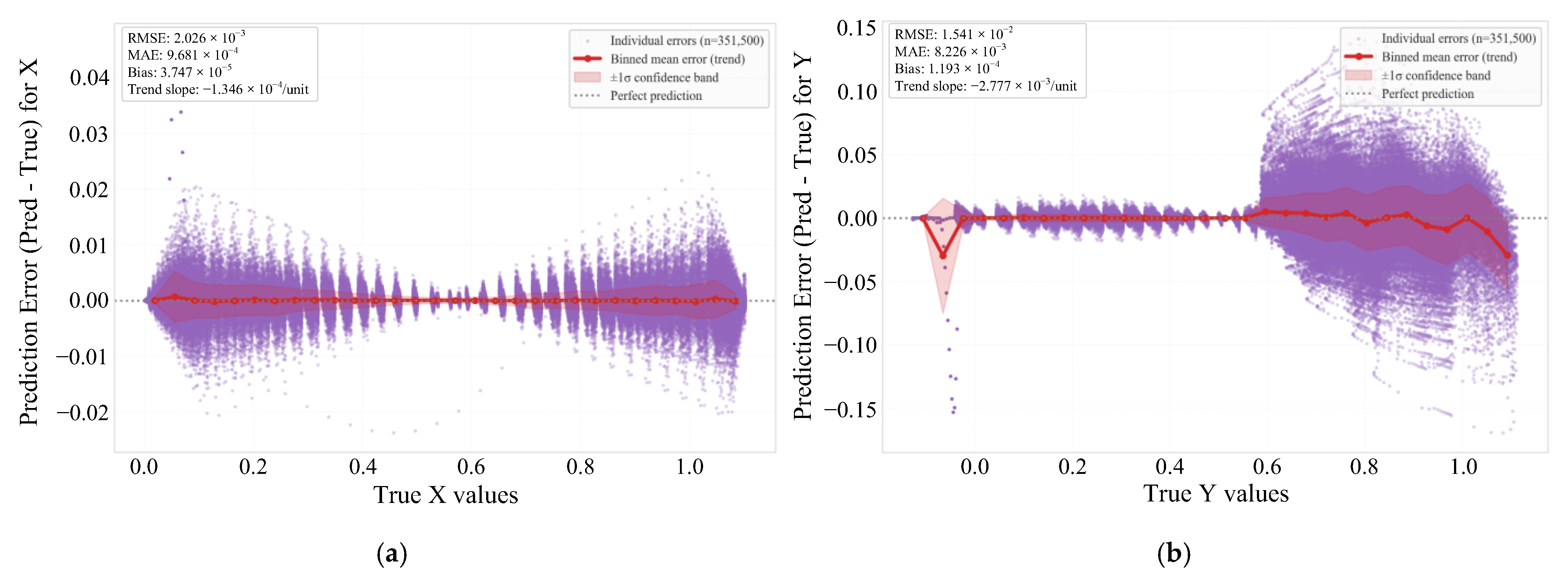

5.2. Evaluation of Transformer Model Prediction Performance

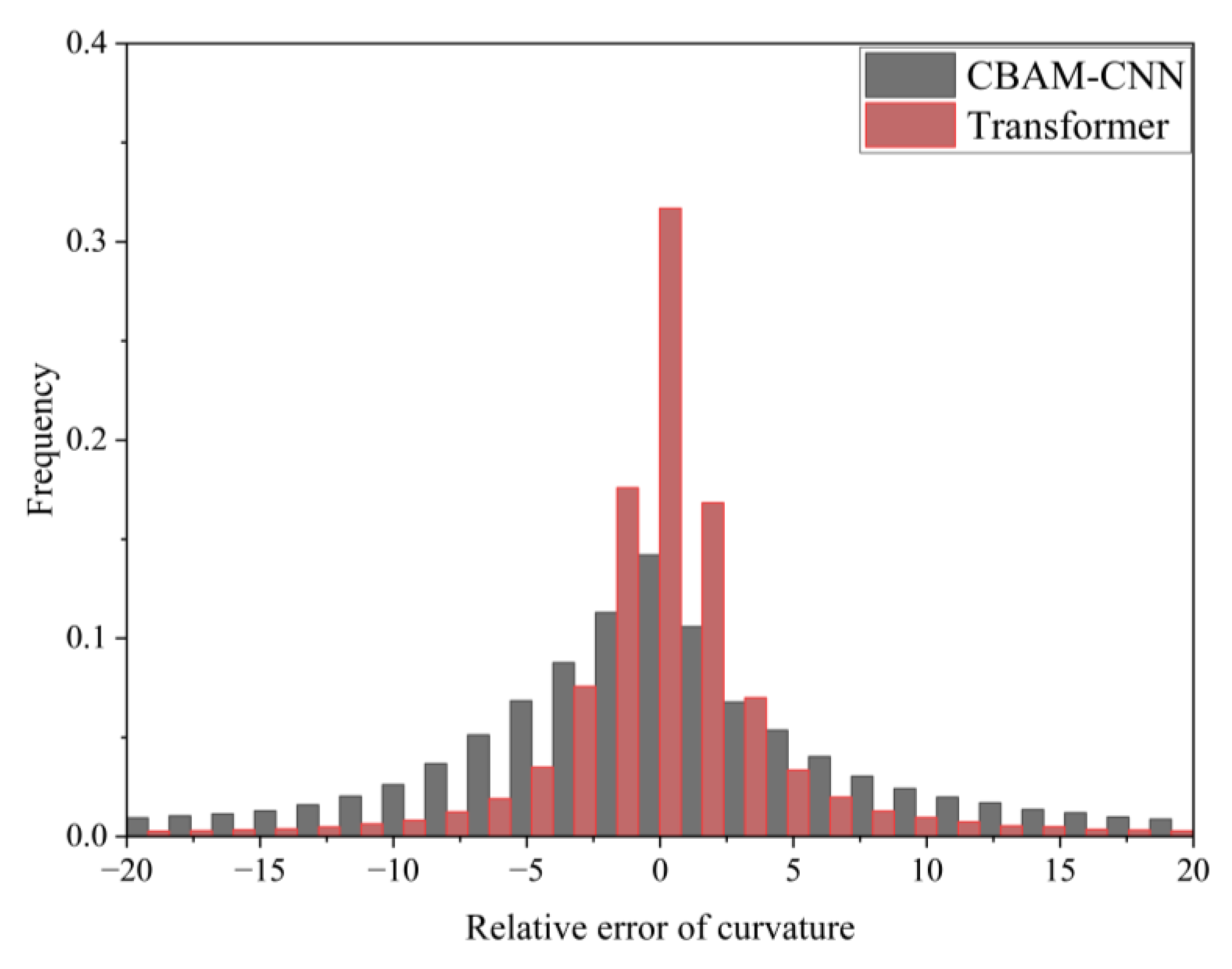

5.3. Model Prediction Accuracy and Error Statistical Analysis

6. Conclusions

- (1)

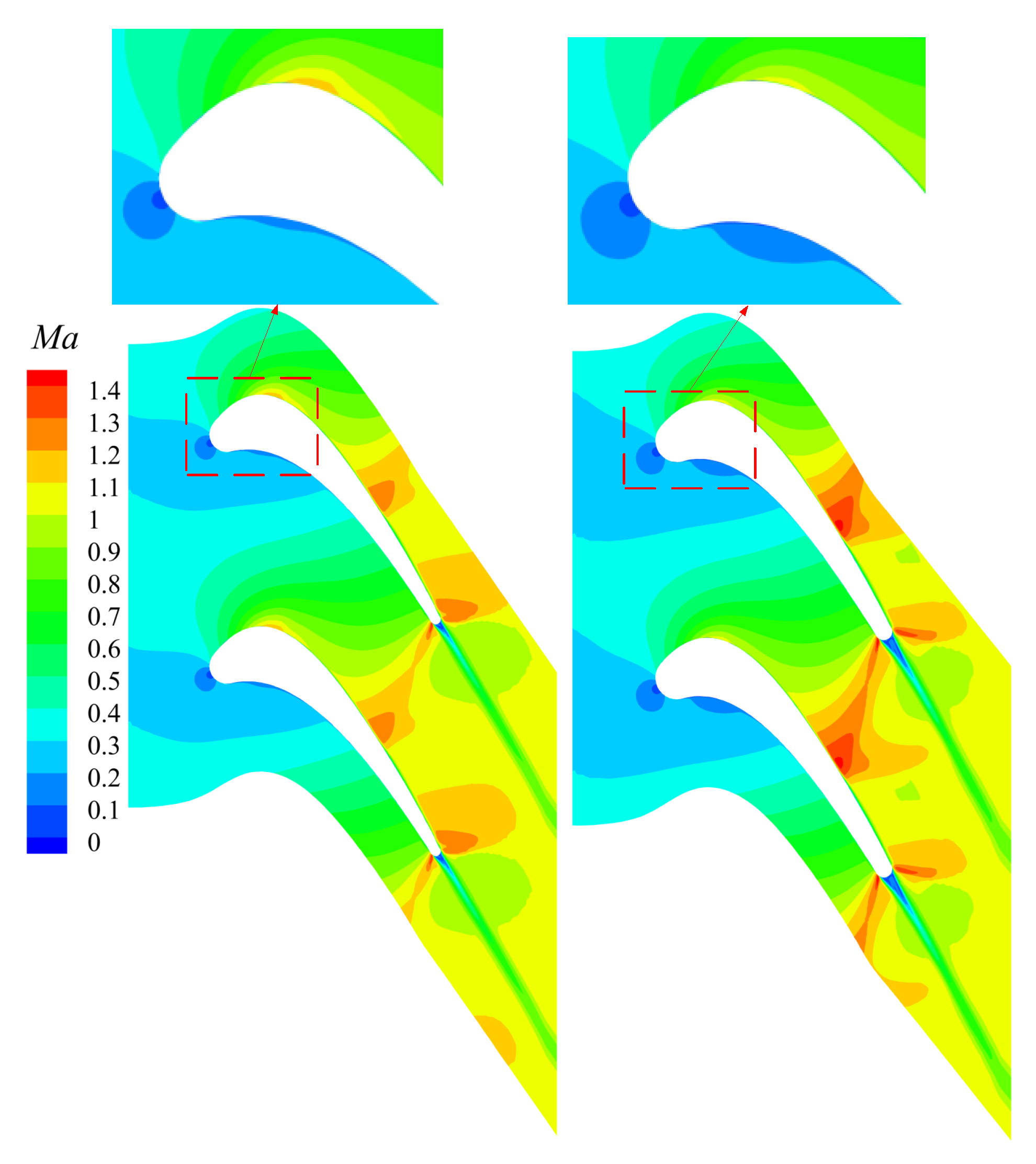

- Compared to traditional “coordinate prediction” methods (such as CNN, MLP), the transformer model can capture complex nonlinear associations between curvature changes and geometric parameters, generating globally continuous blade coordinates. This method successfully suppressed non-physical solution phenomena in supersonic viscous flow fields, improved the uniformity of pressure gradients in the optimized blade profile, inhibited local flow separation, and provided a high-precision, low-computational-cost solution for the inverse design of turbine blade profiles.

- (2)

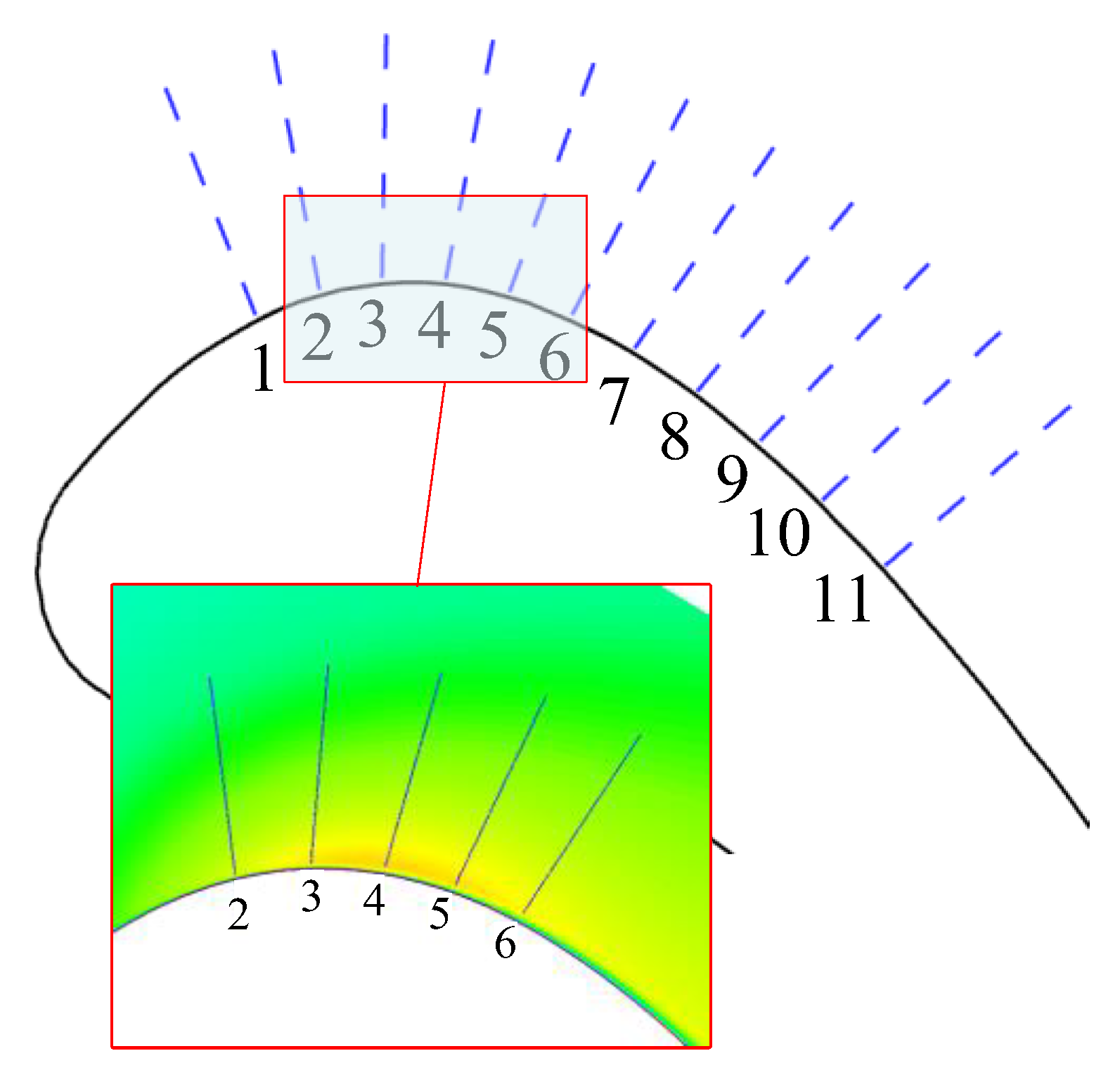

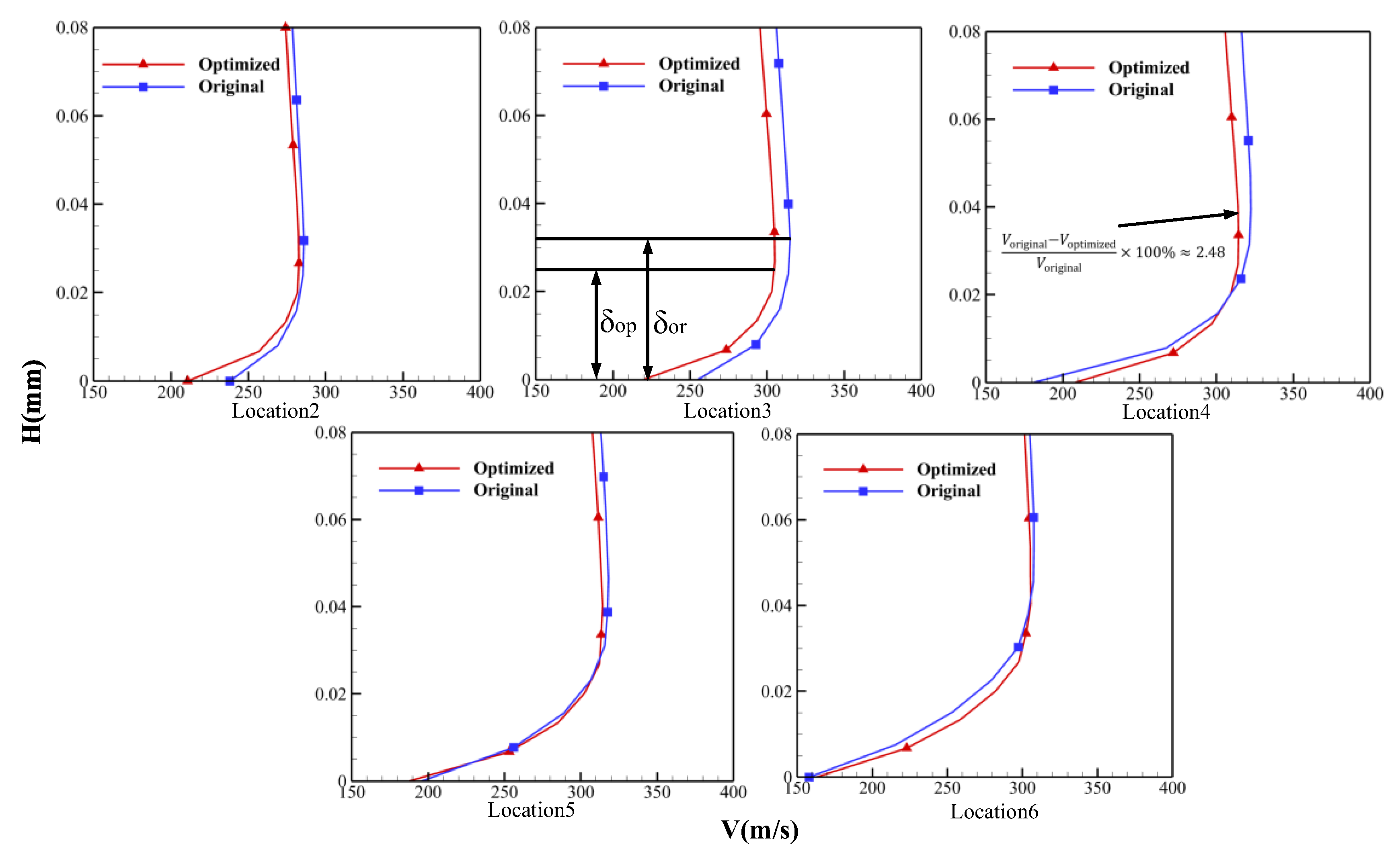

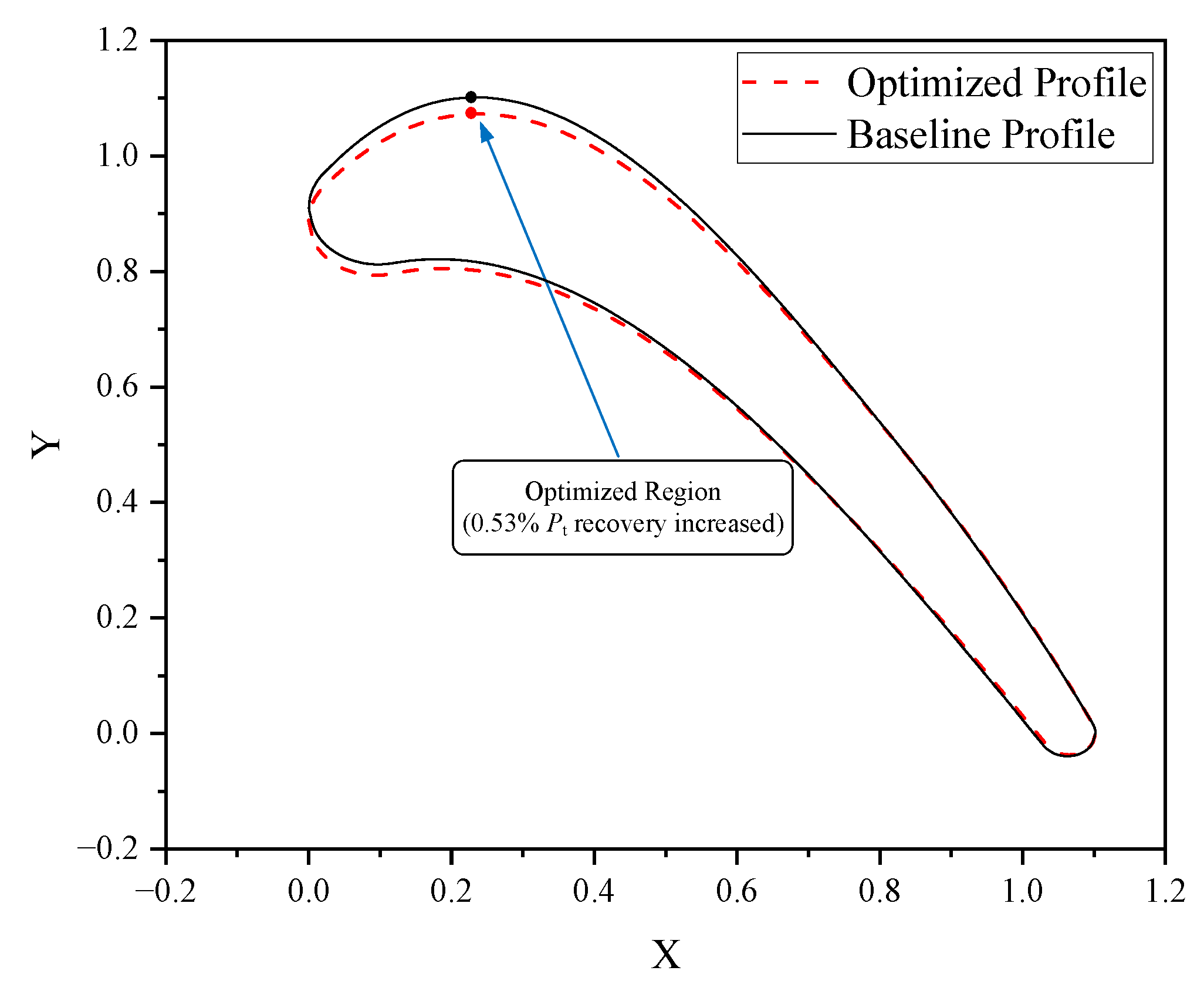

- CFD results show that the optimized blade profile has a thinner boundary layer in the acceleration zone and smoother flow acceleration, verifying the effectiveness of this method in local aerodynamic optimization. The suction surface velocity peak was reduced by 2.48%, the total pressure recovery coefficient increased from 0.949 to 0.954 (a relative improvement of 0.53%), and the total pressure loss coefficient decreased from 0.744 to 0.663, demonstrating comprehensive aerodynamic improvements.

- (3)

- This paper proposes a performance matching metric based on BERT embedding and cosine similarity, which achieves quantitative evaluation of the proximity between predicted blade profiles and target designs by mapping Mach number distributions to high-dimensional vectors and calculating cosine similarity. This metric can effectively reflect the model’s generalization ability and provide quantifiable feedback for design optimization directions.

- (4)

- Compared to the traditional CNN-CBAM model, the self-attention mechanism of the transformer model can avoid the field-of-view limitations of a CNN’s local convolution kernels. In key regions, the curvature smoothness of blade profiles generated by the transformer model is superior to that of CNN-CBAM.

- (5)

- Using the sequence-to-sequence transformer optimization method for aerodynamic optimization of a turbine cascade takes approximately 100 s, avoiding the multiple iterative correction processes of traditional modeling optimization and numerical simulations, improving design optimization precision and efficiency, and providing a new method for the intelligent optimization design of turbine blades.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Notations | |

| 1 | Inlet flow angle |

| b | Boundary condition vector |

| Cx | Blade axial chord length |

| d, dk | (Key/Query) vector dimension |

| DKL | Kullback–Leibler Divergence |

| Ma1 | Inlet Mach number |

| Mais | Isentropic Mach number |

| Mpred (x) | Mach number distribution of the model-predicted blade profile |

| Mture (x) | Theoretically designed Mach number distribution |

| P* | Total pressure |

| P2 | Outlet static pressure |

| PE | Positional Encoding |

| pos | Position in the sequence |

| Q, K, V | Query, Key, Value vectors in the attention mechanism |

| Rle | Radius of the blade leading edge |

| Rte | Radius of the blade trailing edge |

| T* | Total temperature |

| vpred, vture | Vectors of Mach number distributions after BERT embedding |

| x, y | Blade geometric coordinates |

| βin | Inlet blade angle |

| βout | Outlet blade angle |

| γin | Inlet wedge angle |

| ξ | Blade unguided turning angle |

| Subscripts | |

| in | Inlet parameter |

| out | Outlet parameter |

| le | Leading Edge |

| te | Trailing Edge |

| pred | Model-predicted value |

| ture | True/Designed value |

Abbreviations

| BERT | Bidirectional encoder representation from transformers |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| FFNN | Feedforward neural network |

| CBAM | Improved convolutional block attention module |

| KL | Kullback–Leibler Divergence |

| LHS | Latin Hypercube Sampling |

| MLP | Multi-layer perceptron |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| ReLU | Rectified linear unit |

References

- Bahrani, N. Multidisciplinary Design Optimization of Turbomachinery Blade. Master′s Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xiang, L.; Kang, E.; Xia, J.; Wang, C.; Yan, C. Multidisciplinary Design Optimization of Cooling Turbine Blade: An Integrated Approach with R/ICSM. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maral, H.; Alpman, E.; Kavurmacıoğlu, L.; Camci, C. A Genetic Algorithm Based Aerothermal Optimization of Tip Carving for an Axial Turbine Blade. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 143, 118419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y. A Parameterized-Loading Driven Inverse Design and Multi-Objective Coupling Optimization Method for Turbine Blade Based on Deep Learning. Energy 2023, 281, 128209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, W.R.; Wang, C.; Tan, C.S.; McCune, J.E. Theory of Blade Design for Large Deflections: Part I—Two-Dimensional Cascade. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1984, 106, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Hawthorne, W.; McCune, J.; Wang, C. Theory of Blade Design for Large Deflections: Part II—Annular Cascades. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1984, 106, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J. A Three-Dimensional Inverse Method for Turbomachinery: Part I—Theory. J. Turbomach. 1990, 112, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh, M. A Compressible Three-Dimensional Design Method for Radial and Mixed Flow Turbomachinery Blades. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 1991, 13, 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeulenaere, A.; Van Den Braembussche, R. Three-Dimensional Inverse Method for Turbomachinery Blading Design. J. Turbomach. 1998, 120, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T. Evaluation of 3D Inverse Code Using Rotor 67 as Test Case; CR-1998-206994; Technical Report; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X.; Dang, T. 3D Inverse Method for Turbomachine Blading with Splitter Blades. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2000: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Atlanta, GA, USA, 12–15 June 2000; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Thompkins, J.; Tong, S. Inverse or Design Calculations for Nonpotential Flow in Turbomachinery Blade Passages. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1982, 104, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Thompkins, J. A Design Calculation Procedure for Shock-Free or Strong Passage Shock Turbomachinery Cascades. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1983, 105, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabi, A.; Ghaly, W. Inverse Design of Turbine and Compressor Stages Using a Commercial CFD Program. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2013: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–7 June 2013; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, B. Adjoint Method-Based Inverse Design of Transonic Compressor Cascade with Boundary Layer Control. Prog. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 2017, 17, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ju, Y.; Zhang, C. An Experience-Independent Inverse Design Optimization Method of Compressor Cascade Airfoil. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A-J. Power Energy 2019, 233, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.X.; Li, Y.S. 3D Direct and Inverse Design Using NS Equations and the Adjoint Method for Turbine Blades. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2010: Power for Land, Sea and Air, Glasgow, UK, 14–18 June 2010; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2010. GT2010-22049. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Z.; Shao, F.; Wu, H. Transpiration Boundary Condition Based on Inverse Method for Turbomachinery Aerodynamic Design: On the Solution Existence and Uniqueness. J. Propuls. Technol. 2015, 36, 579–586. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chang, J.; Kong, C.; Bao, W. Recent Progress of Machine Learning in Flow Modeling and Active Flow Control. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 14–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chang, J.; Wang, Z.; Kong, C. Inversion and Reconstruction of Supersonic Cascade Passage Flow Field Based on a Model Comprising Transposed Network and Residual Network. Phys. Fluids 2019, 31, 126102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, S.; Jung, O. Prediction of Flow Properties on Turbine Vane Airfoil Surface from 3D Geometry with Convolutional Neural Network. In Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. V02DT46A007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, K.; Luo, Q.; Du, W.; Wang, S. Design Methods and Strategies for Forward and Inverse Problems of Turbine Blades Based on Machine Learning. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 31, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, J.; Li, Y.; Long, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; You, Y. Two-Dimensional Temperature Field Inversion of Turbine Blade Based on Physics-Informed Neural Networks. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 037114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duta, M.C.; Duta, M.D. Multi-Objective Turbomachinery Optimization Using a Gradient-Enhanced Multi-Layer Perceptron. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2009, 61, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, R.; Osama, S.; Ahmed, H.; Nasser, M.; Mahmoud, N.; Elkodama, A.; Ismaiel, A. Parametric Analysis Towards the Design of Micro-Scale Wind Turbines: A Machine Learning Approach. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Reissmann, M.; Pacciani, R.; Zhao, Y.; Ooi, A.S.H.; Marconcini, M.; Akolekar, H.D.; Sandberg, R.D. Exploiting a Transformer Architecture for Simultaneous Development of Transition and Turbulence Models for Turbine Flow Predictions. In Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2024; p. V12CT32A023. [Google Scholar]

- Aulich, M.; Goinis, G.; Voß, C. Data-Driven AI Model for Turbomachinery Compressor Aerodynamics Enabling Rapid Approximation of 3D Flow Solutions. Aerospace 2024, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamakhan, I.A.; Korakianitis, T. Aerodynamic Performance Effects of Leading-Edge Geometry in Gas-Turbine Blades. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Qin, K.; Huang, D. Effect of Streamwise Bionic Protuberances with Continuous Curvature Near the Leading Edge on Performance of Compressor Cascade Aerodynamics. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2025, 19, 2578015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, L.J. An Eleven Parameter Axial Turbine Airfoil Geometry Model. In Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1985; p. V001T03A058. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.; Ma, W.; Feng, F. Research on the Shock Wave Structure and Its Evolution in Turbine Cascades. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 2015, 35, 571–575. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, B.; Lomax, H. Thin-Layer Approximation and Algebraic Model for Separated Turbulent Flows. In Proceedings of the 16th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Reno, NV, USA, 16–19 January 1978; p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, T.; Ji, L.; Zhou, L. Application of Neural Network Model in Compressor Through-Flow Analysis. J. Aerosp. Power 2022, 37, 1260–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, T.; Ji, L. Application of New Empirical Models Based on Mathematical Statistics in the Through-Flow Analysis. J. Therm. Sci. 2021, 30, 2087–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, T.; Ji, L.; Yi, W. Performance Characteristic Modeling for 2D Compressor Cascades. Int. J. Turbo Jet-Engines 2022, 39, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, L.J.; Seashultz, R.G. Laser Anemometer Measurements in an Annular Cascade of Core Turbine Vanes and Comparison with Theory; Technical Report; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Range |

|---|---|

| Blade unguided turning, ξ (°) | 3.5~9.0 |

| Inlet blade angle, βin (°) | remain constant |

| Inlet wedge angle, γin (°) | 5.0~20.0 |

| Radius of the blade leading edge, Rle (mm) | 0.05~0.10 |

| Outlet blade angle, βout (°) | remain constant |

| Radius of the blade trailing edge, Rte (mm) | 0.012~0.040 |

| Blade axial chord, Cx (mm) | 30.0~40.0 |

| Boundary Conditions | Range |

|---|---|

| Inlet total pressure, (kPa) | 101.32 |

| Inlet total temperature, (K) | 288.15 |

| Inlet flow angle, (°) | 32.6 |

| Inlet mach number, Ma1 | 0.3 |

| Outlet static pressure, P2 (kPa) | 40.0~90.0 |

| Radius of the blade trailing edge, Rte (mm) | 0.012~0.040 |

| Blade axial chord, Cx (mm) | 30.0~40.0 |

| Parameter | Value/Description |

|---|---|

| Encoder–decoder layers | 5 layers |

| Layer composition | Multi-head attention, feedforward network, residual connection, layer normalization |

| Hidden nodes (encoder/decoder) | 512 |

| Feedforward hidden nodes | 2048 |

| Number of attention heads | 8 |

| Dropout | 0.1 |

| Input/target sequence processing | Embedding + positional encoding |

| Learning rate scheduler | Noam scheduler |

| Overfitting mitigation | Label smoothing |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Layer Name | Structural Parameters | Output Size | Parameter | Value/Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input Layer | / | 1 × 308 | Encoder–decoder layers | 5 layers |

| Convolutional Layer C1 | CN = 32; CS = 1; stride = 1 | 32 × 308 | Layer composition | Multi-head attention, feedforward network, residual connection, layer normalization |

| Batch Normalization | / | 32 × 308 | Hidden nodes (encoder/decoder) | 512 |

| CBAM1 | / | 32 × 308 | Feedforward hidden nodes | 2048 |

| Pooling Layer P1 | PS = 2; stride = 2 | 32 × 154 | Number of attention heads | 8 |

| Convolutional Layer C2 | CN = 128; CS = 1; stride = 1 | 128 × 154 | Dropout | 0.1 |

| Batch Normalization | / | 128 × 154 | Input/target sequence processing | Embedding + positional encoding |

| CBAM2 | / | 128 × 154 | Learning rate scheduler | Noam scheduler |

| Pooling Layer P2 | PS = 2; stride = 2 | 128 × 77 | Overfitting mitigation | Label smoothing |

| Convolutional Layer C3 | CN = 16; CS = 1; stride = 1 | 16 × 77 | Optimizer | Adam |

| Batch Normalization | / | 16 × 77 | ||

| CBAM3 | / | 16 × 77 | ||

| Pooling Layer P3 | PS = 2; stride = 2 | 16 × 38 | ||

| Flatten | / | 608 (16 × 38) | ||

| Fully Connected FC1 | / | 256 | ||

| Fully Connected FC2 | / | 512 | ||

| Fully Connected FC3 | / | 200 | ||

| Output Layer | / | 200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, S.; Ji, L.; Fei, T.; Zhao, S. A Sequence-to-Sequence Transformer-Based Approach for Turbine Blade Profile Optimization. Aerospace 2026, 13, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010052

Xu S, Ji L, Fei T, Zhao S. A Sequence-to-Sequence Transformer-Based Approach for Turbine Blade Profile Optimization. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Shi, Lucheng Ji, Teng Fei, and Sirui Zhao. 2026. "A Sequence-to-Sequence Transformer-Based Approach for Turbine Blade Profile Optimization" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010052

APA StyleXu, S., Ji, L., Fei, T., & Zhao, S. (2026). A Sequence-to-Sequence Transformer-Based Approach for Turbine Blade Profile Optimization. Aerospace, 13(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010052