Design and Evaluation of an Additively Manufactured UAV Fixed-Wing Using Gradient Thickness TPMS Structure and Various Shells and Infill Micro-Porosities

Abstract

1. Introduction

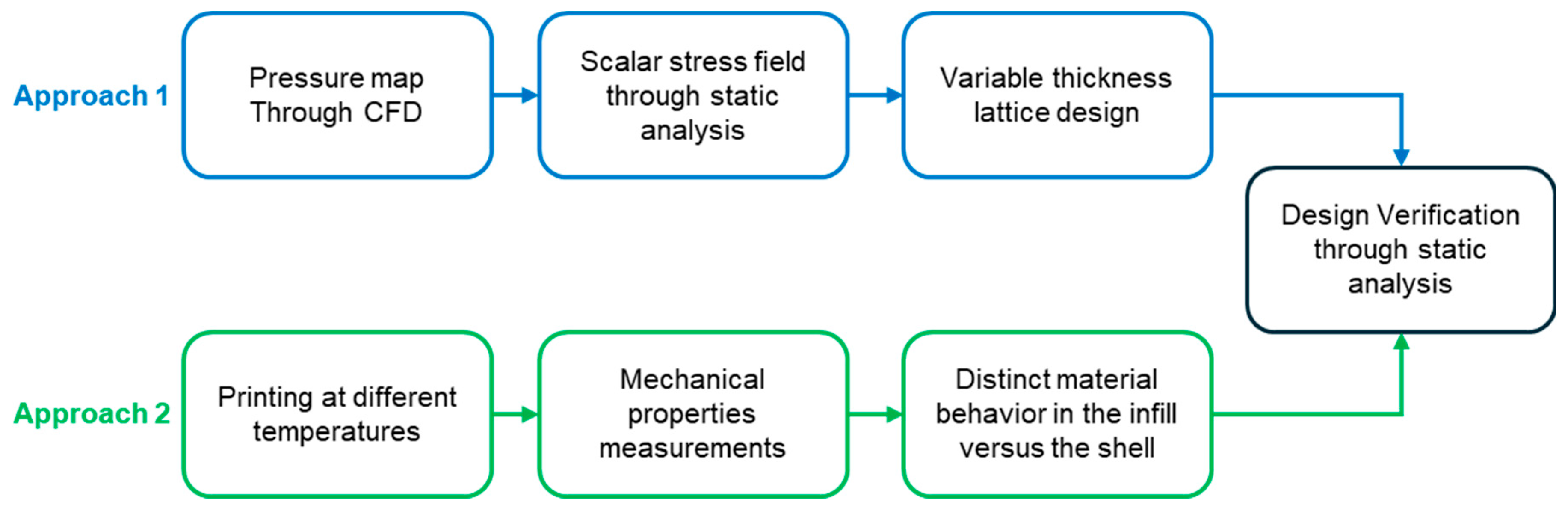

2. Methodology

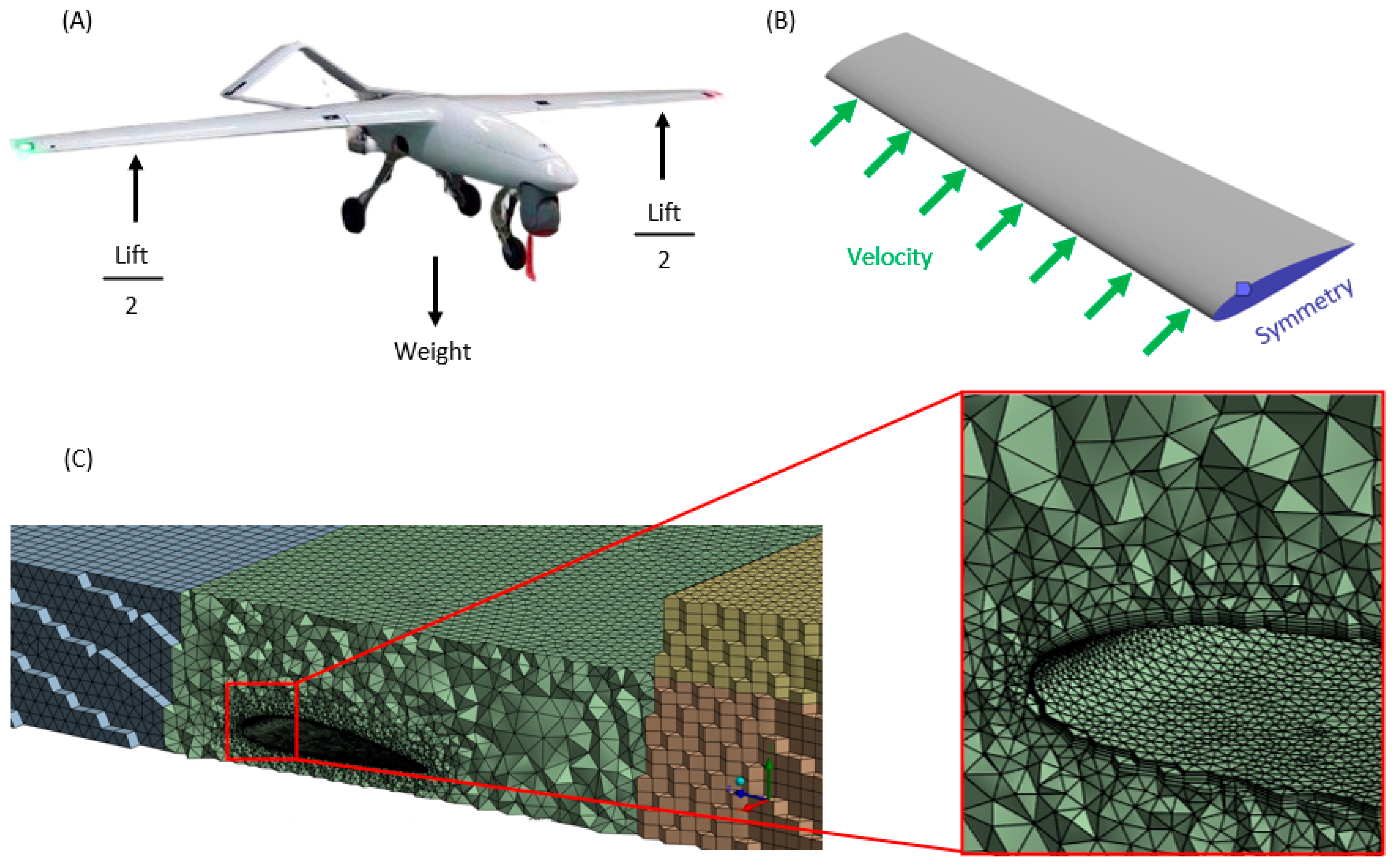

2.1. UAV Reference Platform

2.2. Materials

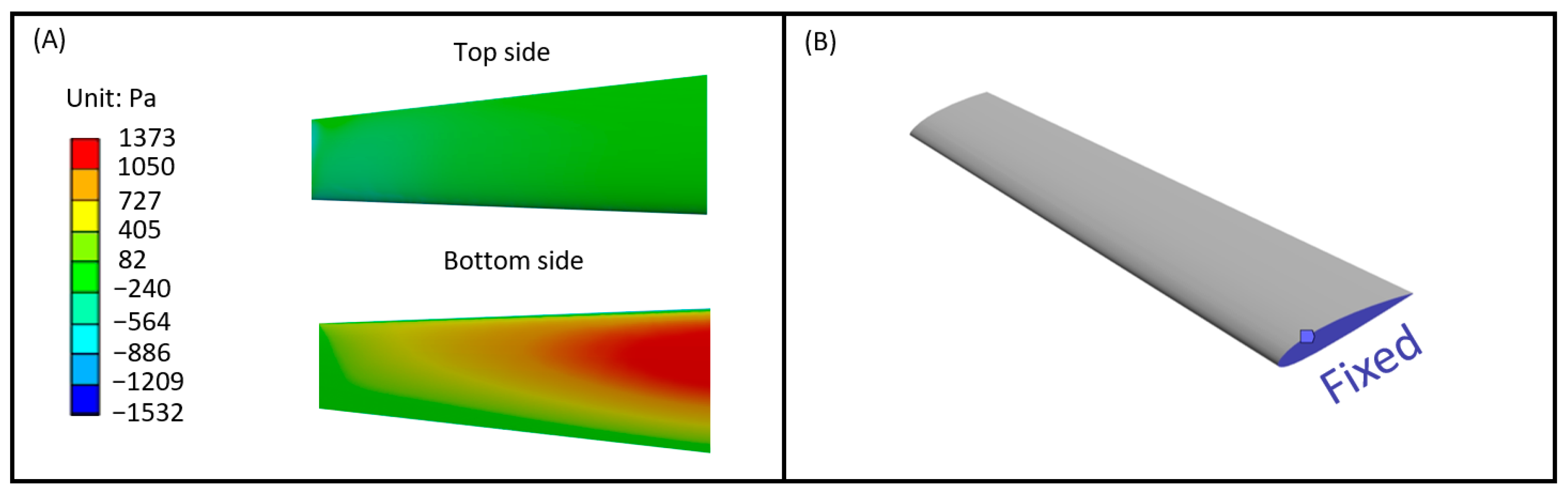

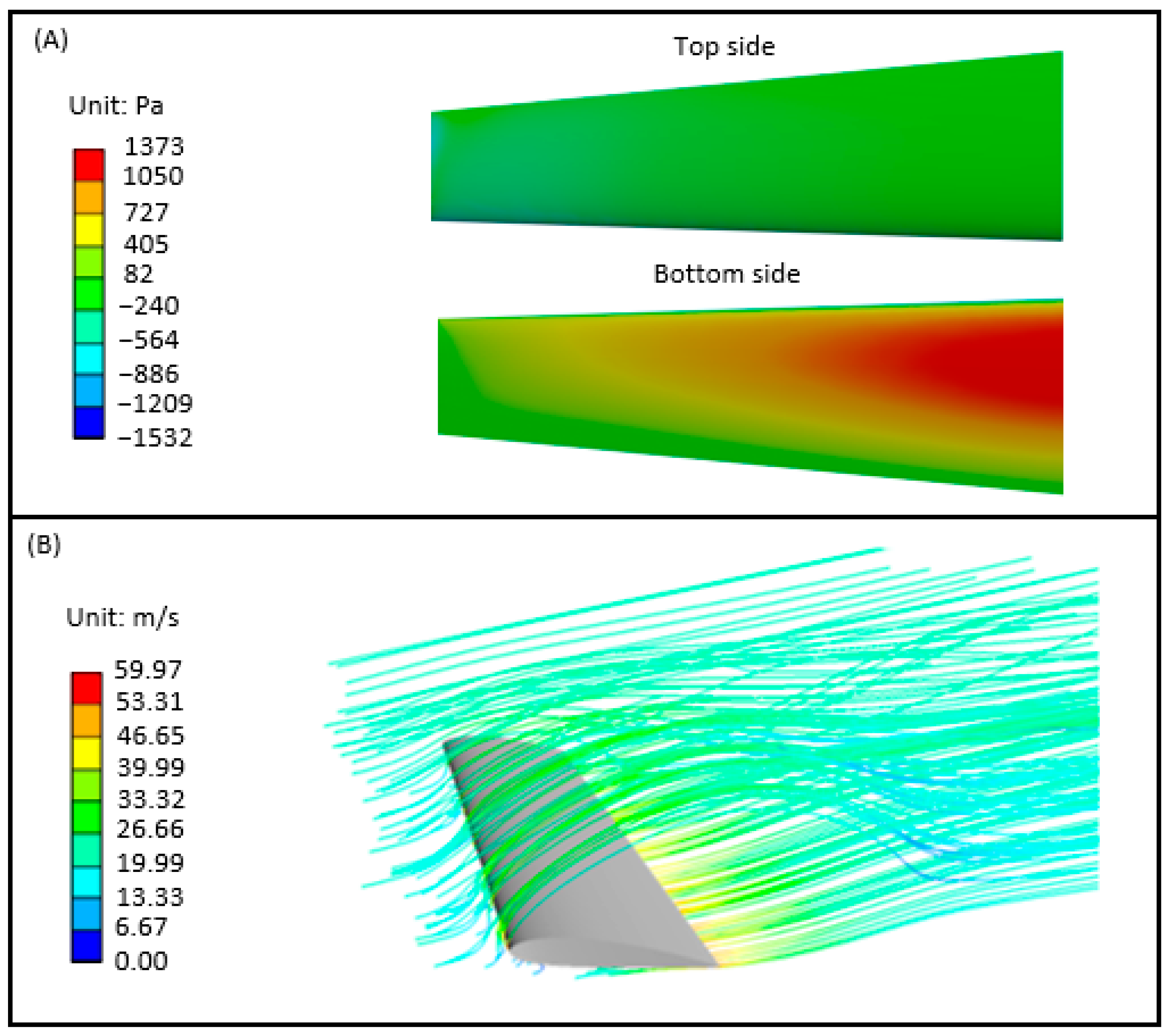

2.3. Computational Fluid Dynamic (CFD) Analysis

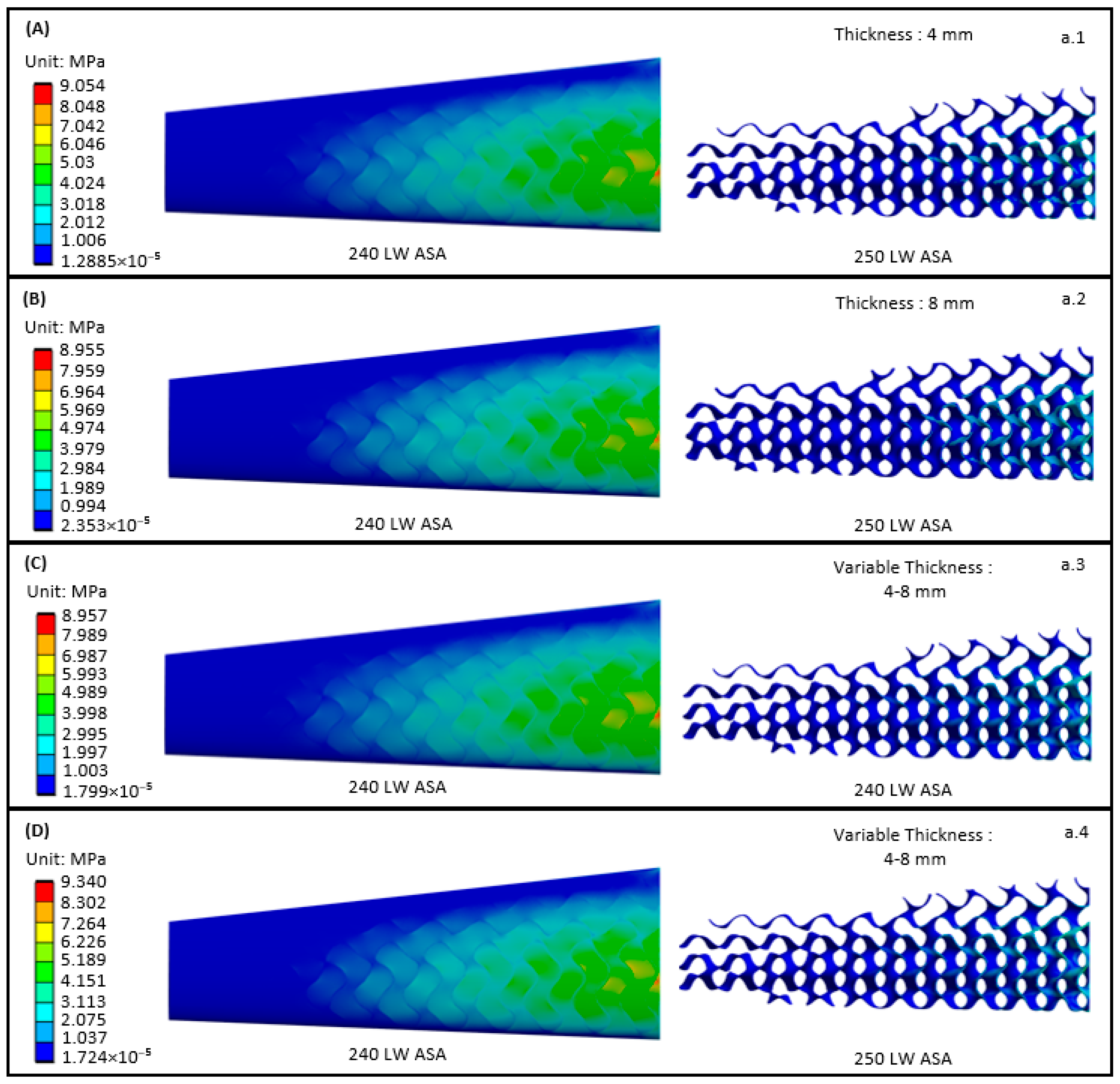

2.4. Static Structural Analysis

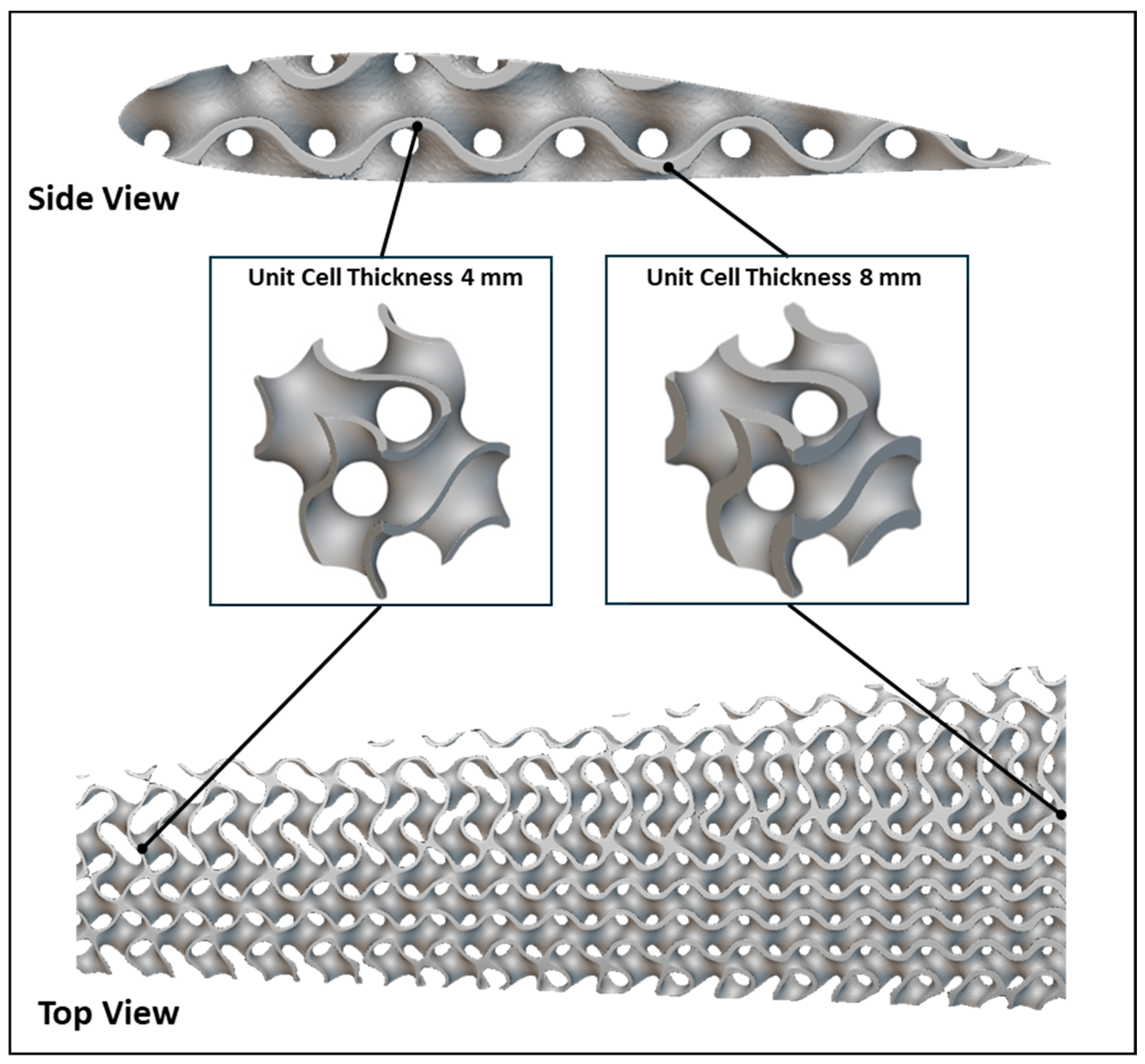

2.5. Variable Thickness Attribution

3. Results

3.1. Material Testing

3.2. CFD Results

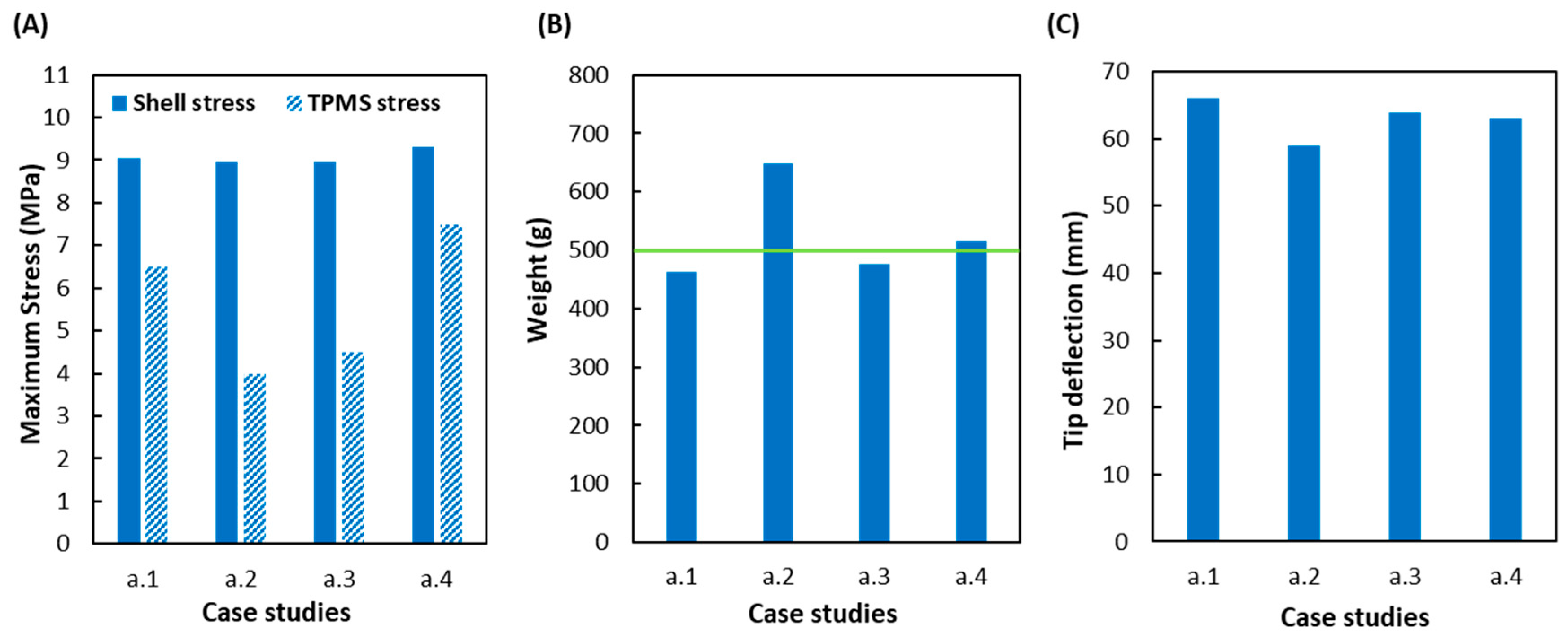

3.3. Static Structural Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Getachew, M.T.; Shiferaw, M.Z.; Ayele, B.S. The current state of the art and advancements, challenges, and future of additive manufacturing in aerospace applications. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 2023, 8817006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D.W.; Espino, M.T.; Cascolan, H.M.; Crisostomo, J.L.; Dizon, J.R.C. A comprehensive review on the application of 3D printing in the aerospace industry. Key Eng. Mater. 2022, 913, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sossou, G.; Demoly, F.; Gomes, S.; Montavon, G. An assembly-oriented design framework for additive manufacturing. Designs 2022, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaggar, G.B.; Dsouza, E.C.; Kamath, A.D. Review on additive manufacturing at the forefront: Exploring recent developments and industry applications. Mater. Res. Proc. 2025, 55, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Zhu, M.; Guest, J.K. Topology optimization considering multi-axis machining constraints using projection methods. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 390, 114464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.; Romero, L.; Domínguez, I.A.; Espinosa, M.D.M.; Domínguez, M. Additive manufacturing technologies: An overview about 3D printing methods and future prospects. Complexity 2019, 2019, 9656938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Miller, J.; Vezza, J.; Mayster, M.; Raffay, M.; Justice, Q.; Al Tamimi, Y.; Hansotte, G.; Devi Sunkara, L.; Bernat, J. Additive manufacturing: A comprehensive review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkcan, H.; Imamoglu, S.Z.; Ince, H. To be more innovative and more competitive in dynamic environments: The role of additive manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 246, 108418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccioni, M.; Ratti, A. Additive manufacturing in the maritime industry: Impact on production processes, workers, and end-users. Hum. Asp. Adv. Manuf. Prod. Manag. Process Control 2024, 146, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez, M.; Pelin, C.-E.; Georgescu, M.; Pelin, G.; Stelescu, M.D.; Nituica, M.; Stoian, G.; Alexandrescu, L.; Gurau, D. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles—Classification, Types of Composite Materials Used in Their Structure and Applications. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Advanced Materials and Systems, Bucharest, Romania, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kantaros, A.; Drosos, C.; Papoutsidakis, M.; Pallis, E.; Ganetsos, T. Composite Filament Materials for 3D-Printed Drone Parts: Advancements in Mechanical Strength, Weight Optimization and Embedded Electronics. Materials 2025, 18, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konyalıoğlu, T.; Alnıpak, S.; Şahin, H.I.; Altuğ, E. Integrating Additive Manufacturing and Composite Manufacturing Techniques to Build a General-Purpose UAV. Int. J. Aviat. Sci. Technol. 2025, 6, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Bhoi, A.; Maurya, V.; Wankhede, A.; Bakshi, R. Design and test 3D printed lattice structure for UAV. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 7, 7169–7174. [Google Scholar]

- Dinovitzer, M.; Miller, C.; Hacker, A.; Wong, G.; Annen, Z.; Rajakareyar, P.; Mulvihill, J.; El Sayed, M. Structural development and multiscale design optimization of additively manufactured uav with blended wing body configuration employing lattice materials. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019; p. 2048. [Google Scholar]

- Lozanovski, B.; Downing, D.; Tino, R.; Tran, P.; Shidid, D.; Emmelmann, C.; Qian, M.; Choong, P.; Brandt, M.; Leary, M. Image-based geometrical characterization of nodes in additively manufactured lattice structures. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 8, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Riccio, A. A systematic review of design for additive manufacturing of aerospace lattice structures: Current trends and future directions. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2024, 149, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A.; Razavi, N.; Benedetti, M.; Murchio, S.; Leary, M.; Watson, M.; Bhate, D.; Berto, F. Properties and applications of additively manufactured metallic cellular materials: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 125, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.; Du Plessis, A.; Ritchie, R.; Dallago, M.; Razavi, N.; Berto, F. Architected cellular materials: A review on their mechanical properties towards fatigue-tolerant design and fabrication. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2021, 144, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panesar, A.; Abdi, M.; Hickman, D.; Ashcroft, I. Strategies for functionally graded lattice structures derived using topology optimisation for Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 19, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Han, Y.; Lu, J. Design and optimization of lattice structures: A review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, D.; Yang, L.; Li, S.; Wang, C.C. Topology optimization of self-supporting lattice structure. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 67, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokollu, B.; Gulcan, O.; Konukseven, E.I. Mechanical properties comparison of strut-based and triply periodic minimal surface lattice structures produced by electron beam melting. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 60, 103199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ketan, O.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K. Multifunctional mechanical metamaterials based on triply periodic minimal surface lattices. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1900524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazerian, H.; Davoodi, E.; Asadi-Eydivand, M.; Kadkhodapour, J.; Solati-Hashjin, M. Porous scaffold internal architecture design based on minimal surfaces: A compromise between permeability and elastic properties. Mater. Des. 2017, 126, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, R.; Jakubinek, M.; Niknam, H.; Rahmat, M.; Ashrafi, B.; Naguib, H.E. 3D printed octet plate-lattices for tunable energy absorption. Mater. Des. 2023, 228, 111835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.; Acanfora, V.; Garofano, A.; Maisto, G.; Riccio, A. An innovative approach to a UAV tails structural design for additive manufacturing. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 11149–11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Liu, K.; Wang, X.; Shen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, K.; Wang, Z. Elastic wave manipulation via functional incorporation of air-solid phases in hybrid TPMS. Compos. Commun. 2023, 44, 101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltsakidis, S.; Tzetzis, D. Review of the Integration of Fused Filament Fabrication with Complementary Methods for Fabricating Hierarchical Porous Polymer Structures. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltsakidis, S.; Tsongas, K.; Tzetzis, D. Combining Micro and Macro Relative Density: An Experimental and Computational Study on Hierarchical Porous 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid Structures. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2402012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltsakidis, S.; Tsongas, K.; Tzetzis, D. Additive Manufacturing of Gradient Stiffness Honeycombs Using Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composite Material Variations. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, e202501422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltsakidis, S.; Tsongas, K.; Tzetzis, D. Robocasting of Hierarchical Porous Al2O3 Structures: A Computational and Experimental Methodology for Porosity Estimation and its Effect. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 34, 16284–16296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Liu, K.; Ma, Q.; Ding, J.; Hu, Z.; Wei, K.; Song, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. Unveiling the mechanics of micro-LPBF manufactured hierarchical composites: A novel FE2-nested homogenisation approach. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2456693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotou, P.; Kaparos, P.; Salpingidou, C.; Yakinthos, K. Aerodynamic design of a MALE UAV. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P.A.C.; Rocha, H.H.B.; Carneiro, F.O.M.; da Silva, M.E.V.; de Andrade, C.F. A case study on the calibration of the k–ω SST (shear stress transport) turbulence model for small scale wind turbines designed with cambered and symmetrical airfoils. Energy 2016, 97, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yan, C.; Han, M.; Ma, M.; Jiang, Z. The improvement of adverse–pressure–gradient eddy viscosity based on the wall law. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 075197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STANAG 4671; Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Systems Airworthiness Requirements (USAR). 1st ed. NATO: Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

- Sankineni, R.; Ravi Kumar, Y. Evaluation of energy absorption capabilities and mechanical properties in FDM printed PLA TPMS structures. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2021, 236, 3558–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Study | TPMS Thickness (mm) | TPMS Printing Temperature (°C) | TPMS Weight (g) | Shell Thickness (mm) | Shell Printing Temperature (°C) | Shell Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a.1 | 4 | 250 | 185 | 1.2 | 240 | 278 |

| a.2 | 8 | 250 | 370 | 1.2 | 240 | 278 |

| a.3 | 4–8 | 250 | 197 | 1.2 | 240 | 278 |

| a.4 | 4–8 | 240 | 237 | 1.2 | 240 | 278 |

| Metric | Conventional Composite Wing (Reference) | Proposed AΜ Methodology | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass (g) | 500 g | 463–648 g (Shell + TPMS) | Up to 7% Lighter |

| Structural Layout | Skin, Spars, Ribs (Multi-part assembly) | Unibody | Assembly effort |

| Manufacturing Method | Hand layup (CF/Fiberglass), Vacuum Bagging/Autoclave | 3D Printing | Automated, Reduced Effort |

| Tooling Required | Molds (CNC machined—3D printed), Vacuum pump | - | Tooling-free |

| Post-Processing | Curing time, Trimming, Assembly gluing | Minimal/Optional Post processing | Reduced Steps |

| Time | 3–5 weeks | 6–10 days | Reduced Time |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moysiadis, G.; Koltsakidis, S.; Ziogas, O.; Panagiotou, P.; Tzetzis, D. Design and Evaluation of an Additively Manufactured UAV Fixed-Wing Using Gradient Thickness TPMS Structure and Various Shells and Infill Micro-Porosities. Aerospace 2026, 13, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010050

Moysiadis G, Koltsakidis S, Ziogas O, Panagiotou P, Tzetzis D. Design and Evaluation of an Additively Manufactured UAV Fixed-Wing Using Gradient Thickness TPMS Structure and Various Shells and Infill Micro-Porosities. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoysiadis, Georgios, Savvas Koltsakidis, Odysseas Ziogas, Pericles Panagiotou, and Dimitrios Tzetzis. 2026. "Design and Evaluation of an Additively Manufactured UAV Fixed-Wing Using Gradient Thickness TPMS Structure and Various Shells and Infill Micro-Porosities" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010050

APA StyleMoysiadis, G., Koltsakidis, S., Ziogas, O., Panagiotou, P., & Tzetzis, D. (2026). Design and Evaluation of an Additively Manufactured UAV Fixed-Wing Using Gradient Thickness TPMS Structure and Various Shells and Infill Micro-Porosities. Aerospace, 13(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010050