An Overview of DC-DC Power Converters for Electric Propulsion

Abstract

1. Introduction

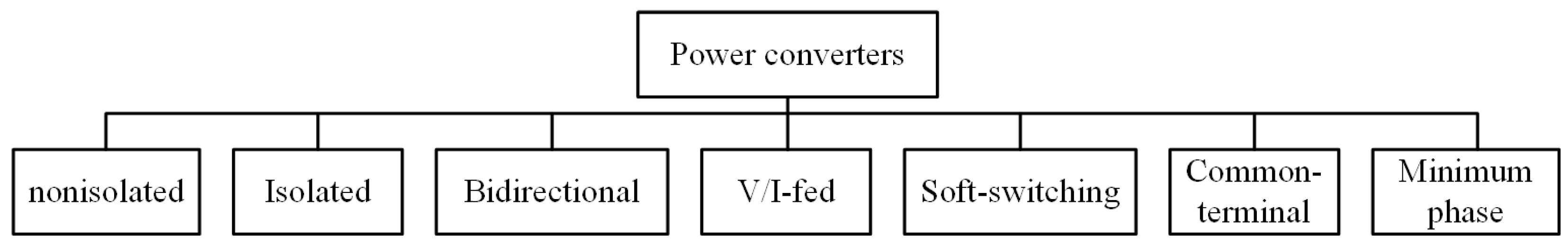

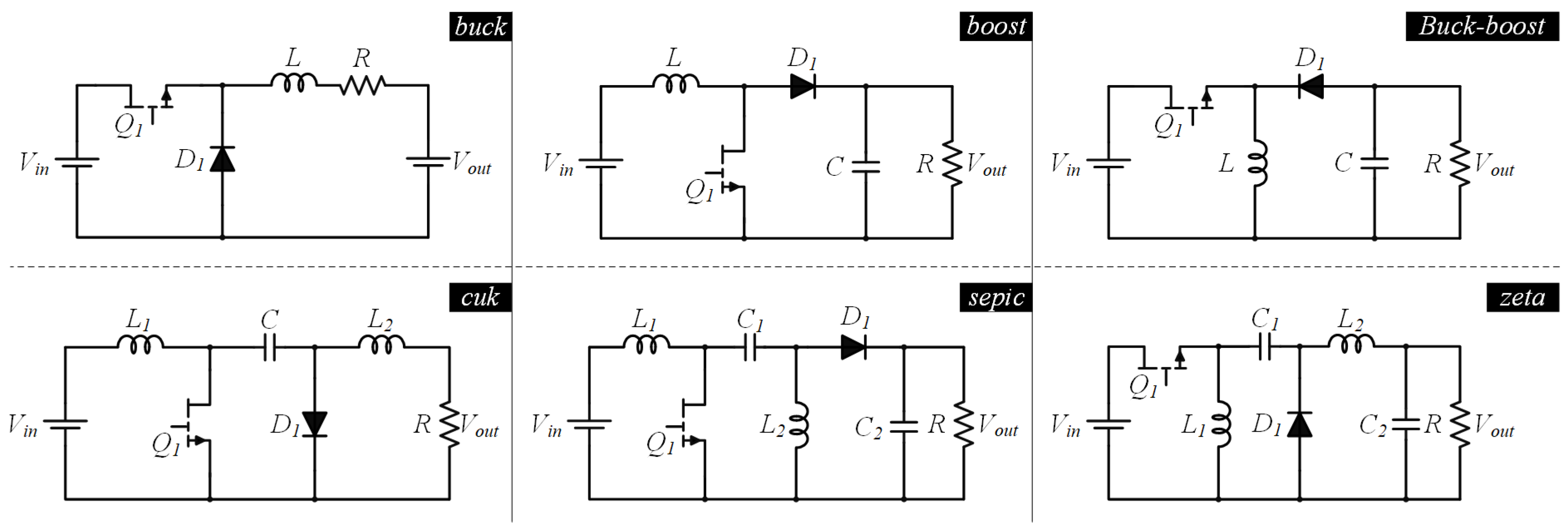

- Non-isolated converters (buck, boost, buck–boost, Cuk, SEPIC, Zeta);

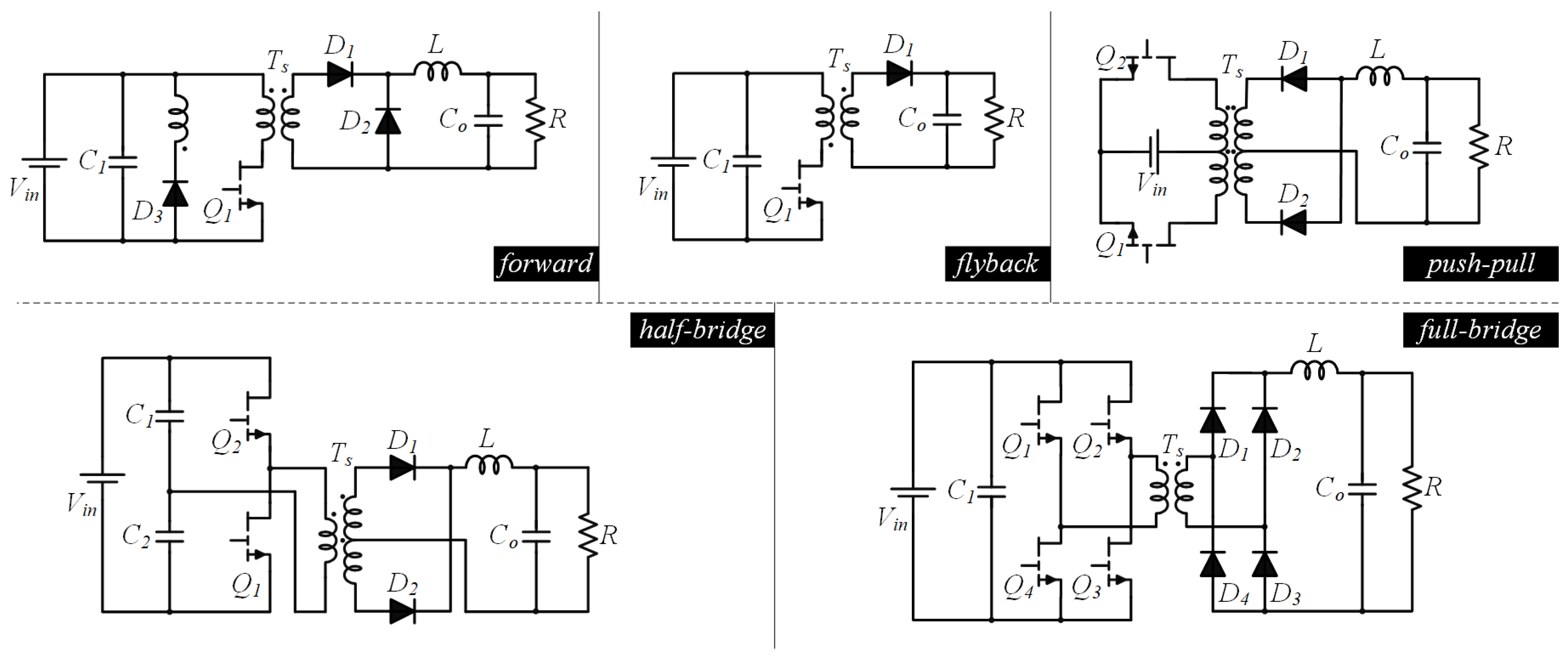

- Isolated converters (forward, flyback, push–pull, half-bridge, full-bridge);

- Bidirectional converters (dual active bridge);

- Voltage-fed and current-fed converters;

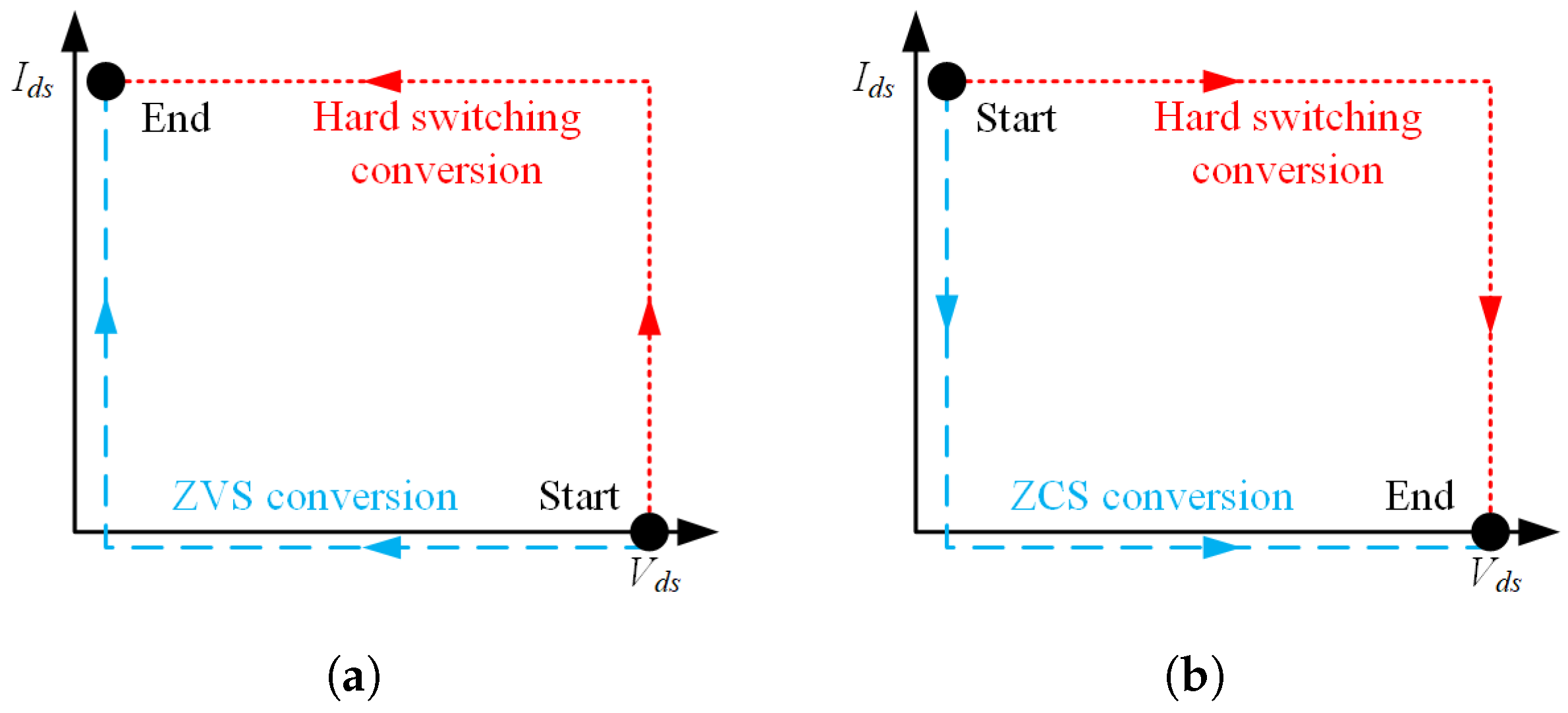

- Soft-switching converters (ZVS/ZCS and resonant topologies);

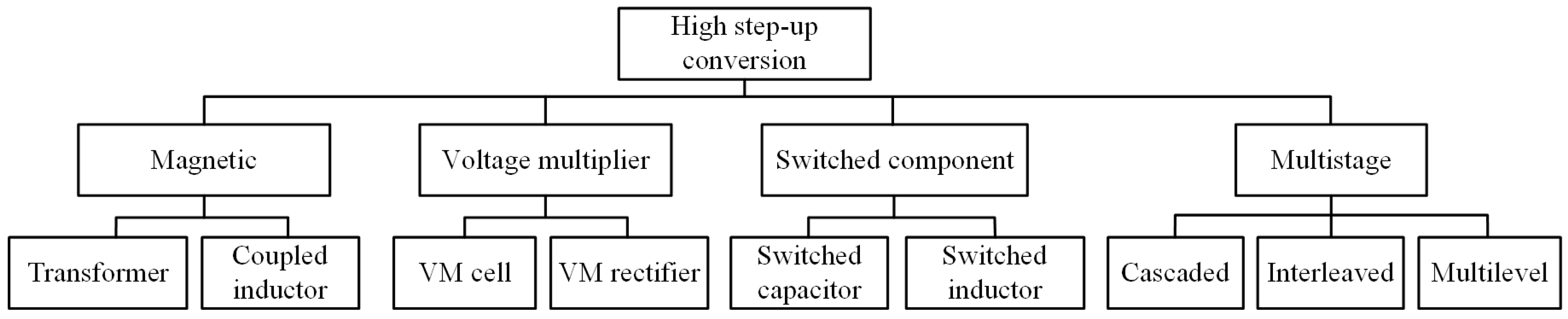

- High step-up conversion techniques (magnetic coupling, voltage multipliers, switched components, multistage configurations).

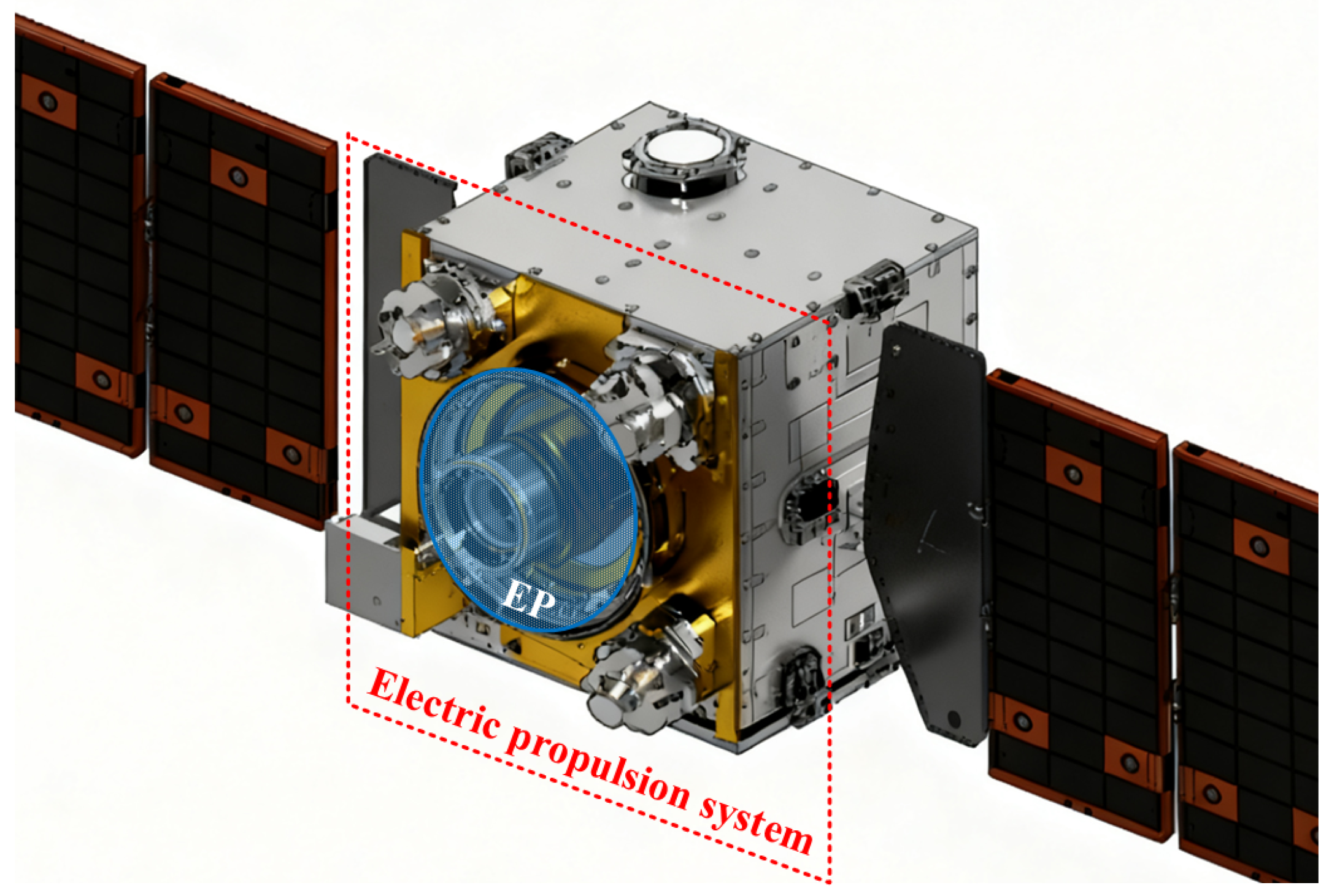

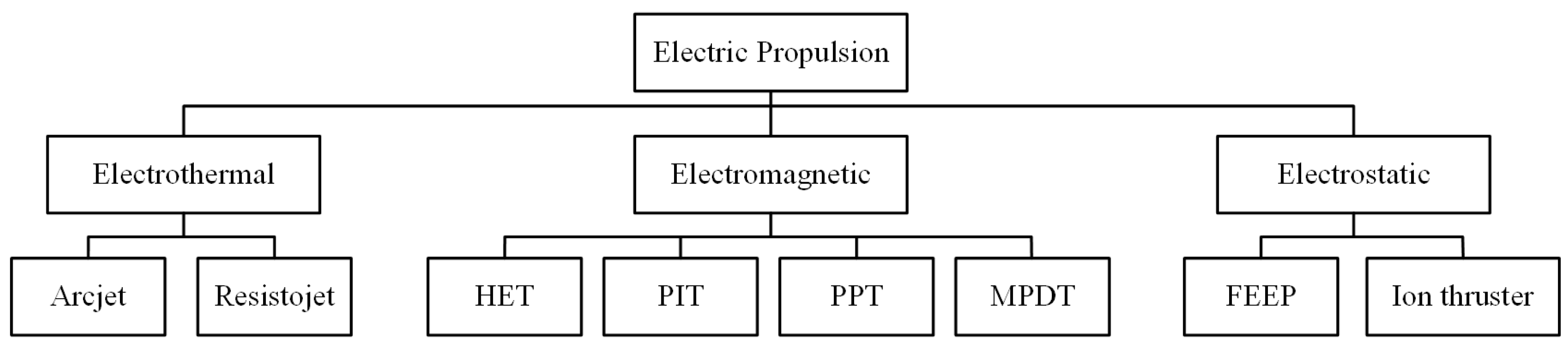

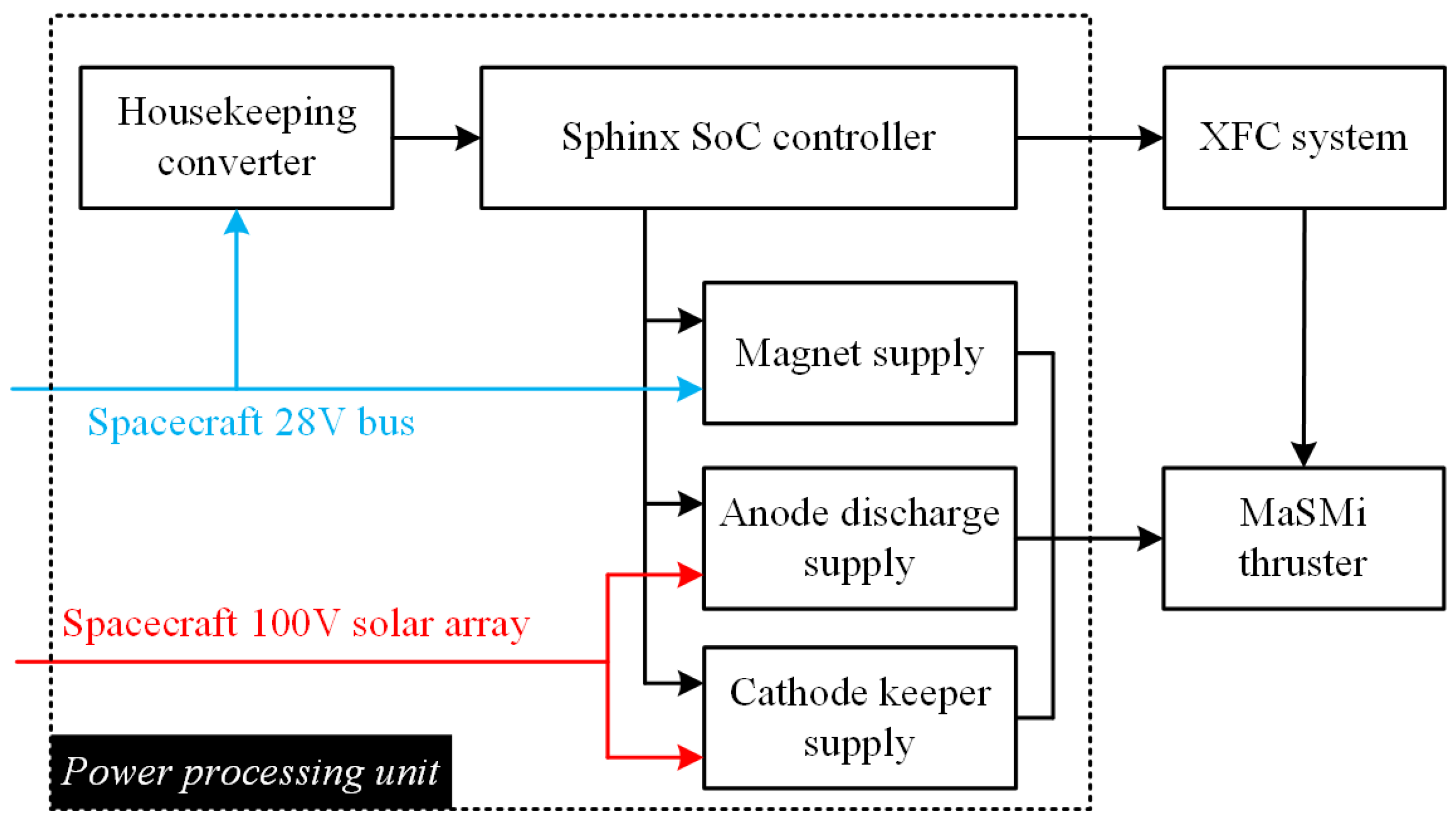

2. Requirements of EP DC-DC Power Converters

3. Classification of EP DC-DC Power Converters

3.1. Non-Isolated Power Converters

3.2. Isolated Power Converters

3.3. Bidirectional Power Converters

3.4. Voltage-Fed/Current-Fed Power Converters

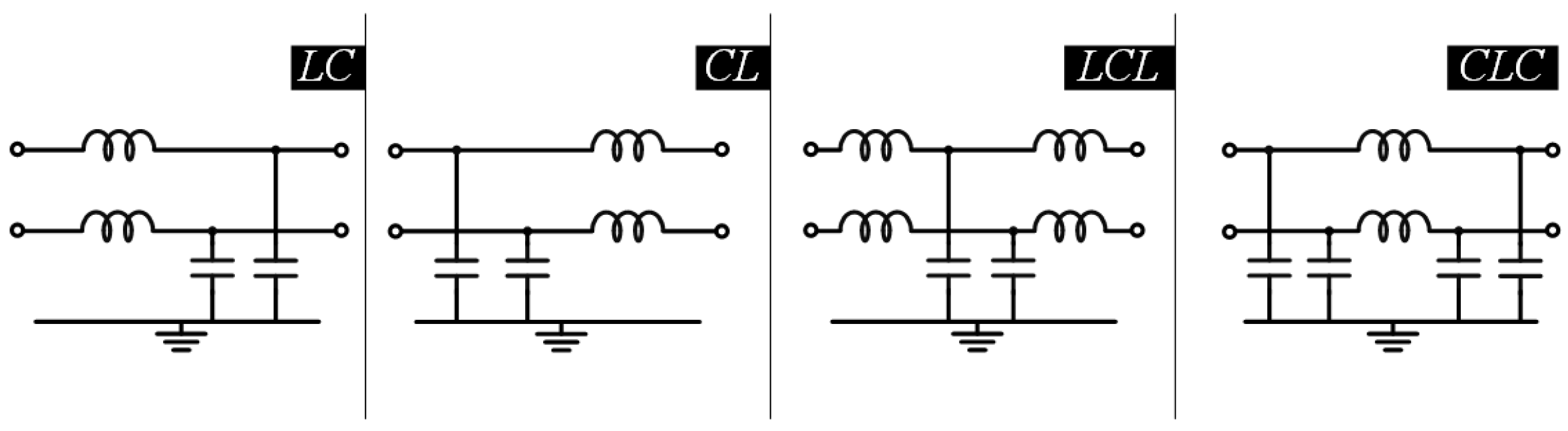

3.5. Soft-Switching Power Converters

3.6. Common-Terminal Power Converters

3.7. Minimum-Phase Power Converters

4. Techniques to Enable High Step-Up Conversion

4.1. Magnetics

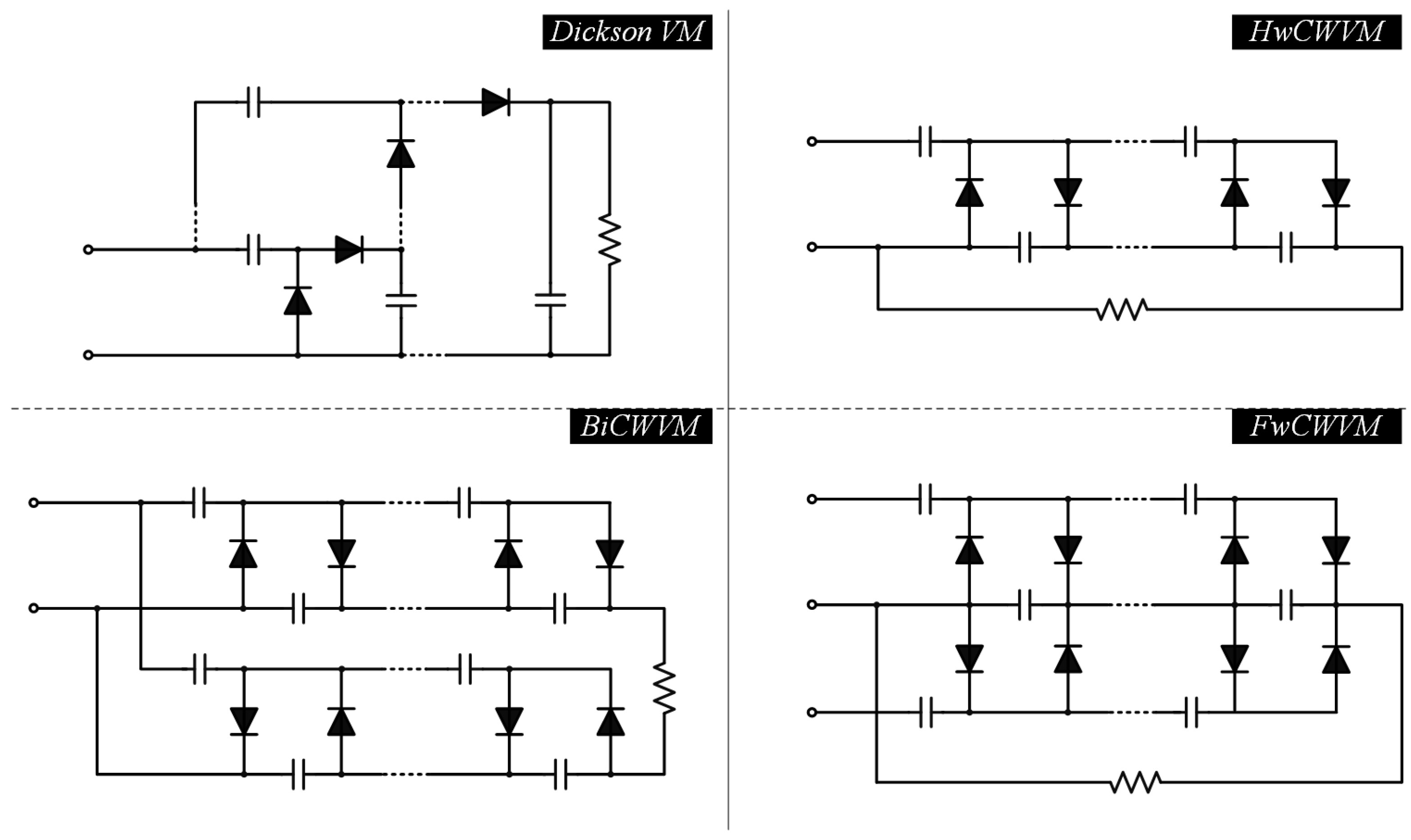

4.2. Voltage Multiplier

4.3. Switched Component

4.4. Multistage

5. Discussion of EP Converters

6. Challenges and Future Works

6.1. Harsh Constraints of Space Environment

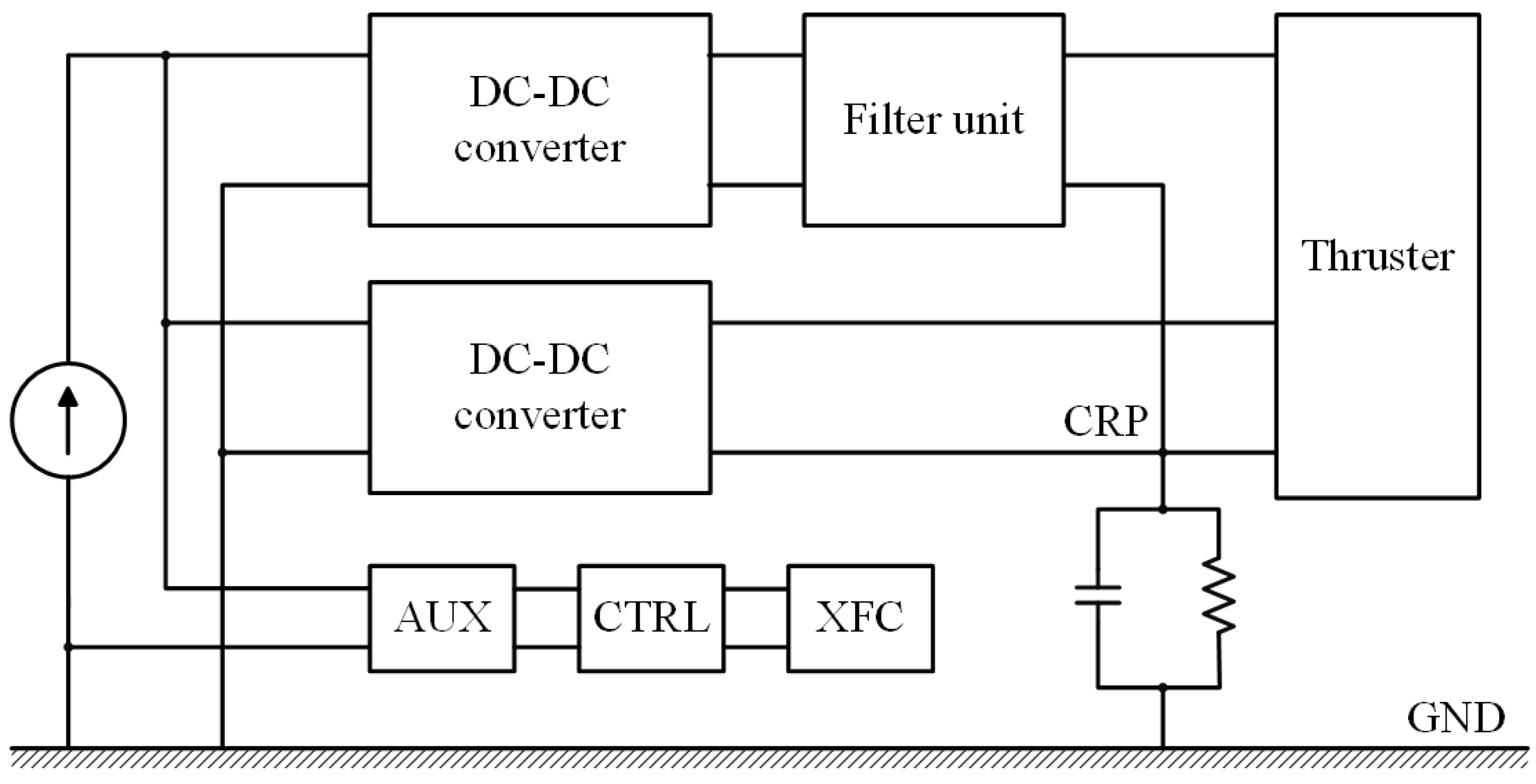

6.2. Direct-Drive Architecture

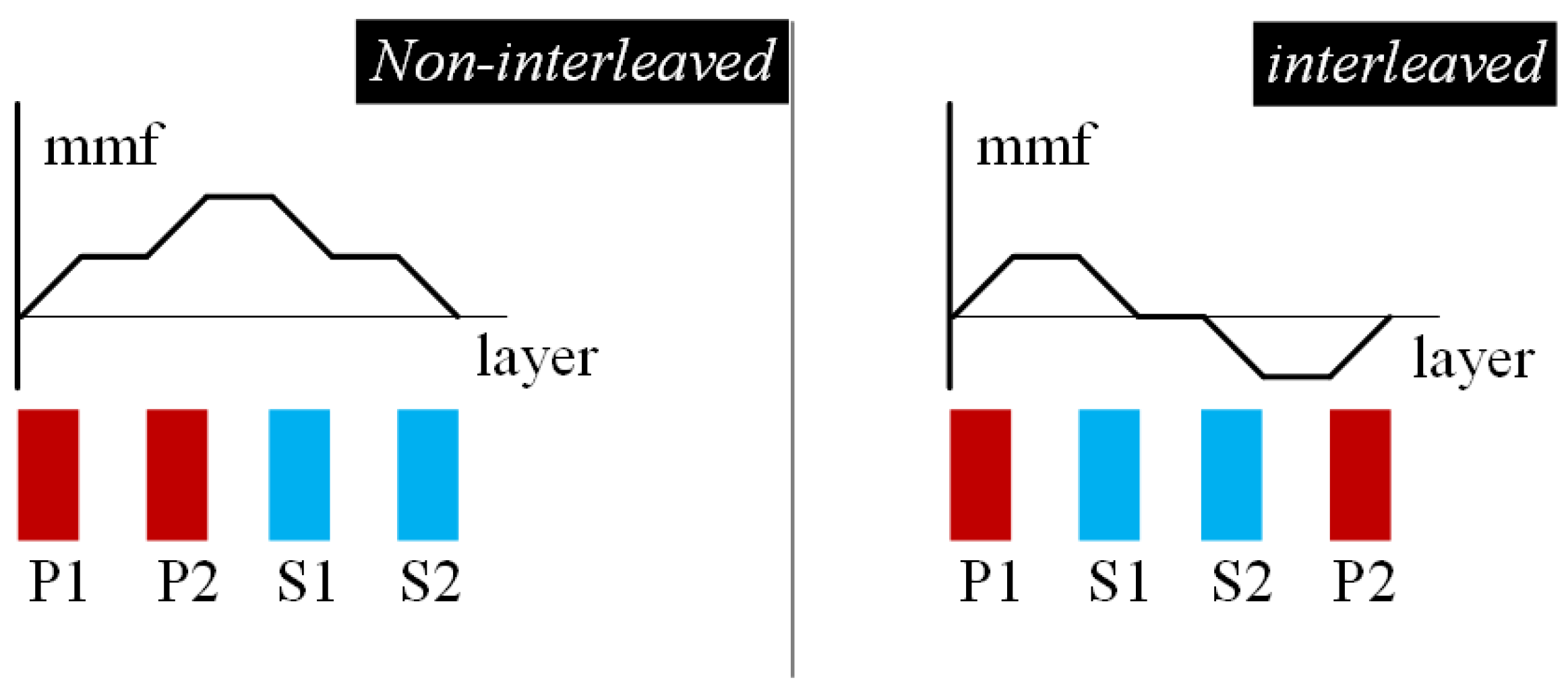

6.3. Planar Magnetics

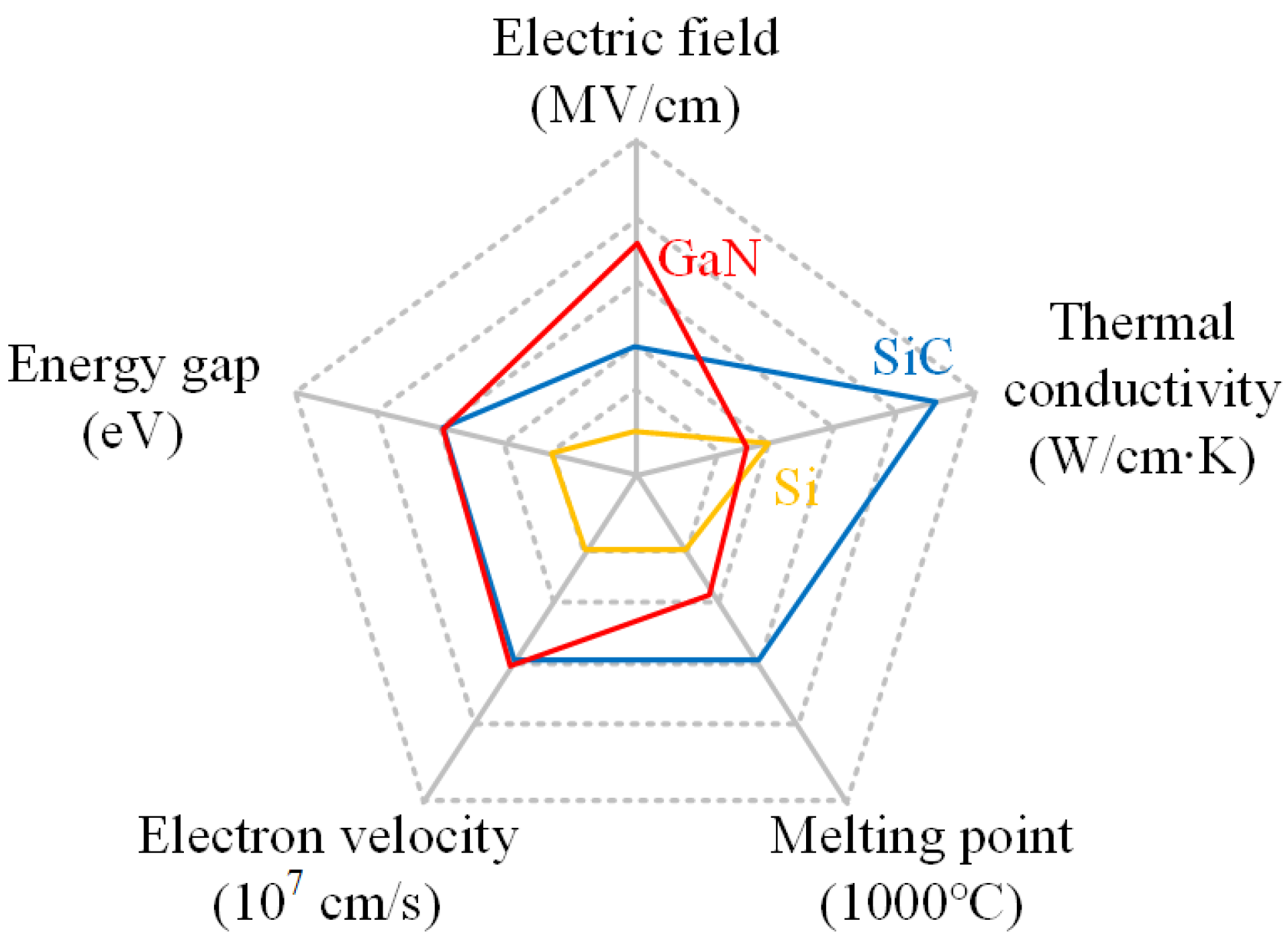

6.4. Wide-Bandgap Devices

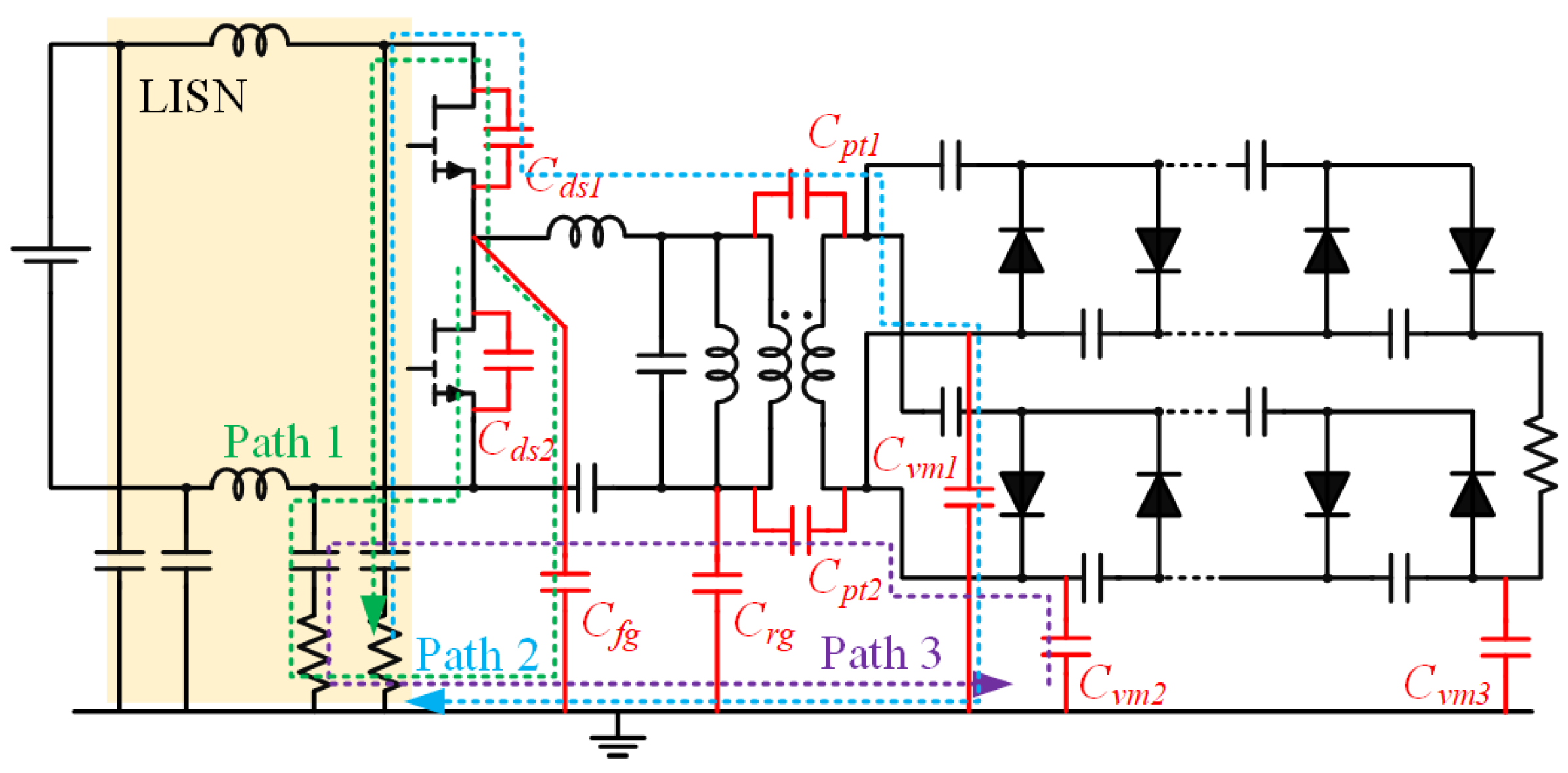

6.5. EMI

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Reilly, D.; Herdrich, G.; Kavanagh, D.F. Electric propulsion methods for small satellites: A review. Aerospace 2021, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummala, A.R.; Dutta, A. An overview of cube-satellite propulsion technologies and trends. Aerospace 2017, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzin, K.; Martin, A.; Little, J.; Promislow, C.; Jorns, B.; Woods, J. State-of-the-art and advancement paths for inductive pulsed plasma thrusters. Aerospace 2020, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OReilly, D.; Herdrich, G.; Schafer, F.; Montag, C.; Worden, S.P.; Meaney, P.; Kavanagh, D.F. A coaxial pulsed plasma thruster model with efficient flyback converter approaches for small satellites. Aerospace 2023, 10, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazouffre, S. Electric propulsion for satellites and spacecraft: Established technologies and novel approaches. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2016, 25, 033002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, D.; Myers, R.M.; Lemmer, K.M.; Kolbeck, J.; Koizumi, H.; Polzin, K. The technological and commercial expansion of electric propulsion. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 159, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, G.; Jacobson, D.; Patterson, M.; Ganapathi, G.; Brophy, J.; Hofer, R. Electric propulsion research and development at NASA. In Proceedings of the International Astronautical Congress, Bremen, Germany, 1–5 October 2018; Number GRC-E-DAA-TN57334. Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pencil, E.J. Recent electric propulsion development activities for NASA science missions. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 7–14 March 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gollor, M.; Bourguignon, E.; Glorieux, G.; Wagner, N.; Palencia, J.; Galantini, P.; Dechent, W.; Franke, A.; Schwab, U.; Tuccio, G. Electric propulsion electronics activities in Europe 2016. In Proceedings of the 52nd AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 25–27 July 2016; p. 5032. [Google Scholar]

- del Amo, J.G. Electric Propulsion at the European Space Agency (ESA). In Proceedings of the 36th International Electric Propulsion Conference, IEPC-2019-105, Vienna, Austria, 15–20 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- del Amo, J.A.G.; Cara, D.M.D. European Space Agency Electric Propulsion Activities. In Proceedings of the International Electric Propulsion Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- del Amo, J.A.G. Electric Propulsion activities at ESA; Technical Report; European Space Agency: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo, J.J.; Brigeman, A.N.; Fain, H.B.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Pinero, L.R.; Birchenough, A.G.; Aulisio, M.V.; Fisher, J.; Ferraiuolo, B. The NEXT-C Power Processing Unit: Lessons Learned from the Design, Build, and Test of the NEXT-C PPU for APL’s DART Mission. In Proceedings of the AIAA Propulsion and Energy 2020 Forum, Virtual Event, 24–28 August 2020; p. 3641. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Woolston, M.; Perreault, D. Design and implementation of a lightweight high-voltage power converter for electro-aerodynamic propulsion. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 18th Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics (COMPEL), Stanford, CA, USA, 9–12 July 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafalskyi, D.; Martínez, J.M.; Habl, L.; Zorzoli Rossi, E.; Proynov, P.; Boré, A.; Baret, T.; Poyet, A.; Lafleur, T.; Dudin, S.; et al. In-orbit demonstration of an iodine electric propulsion system. Nature 2021, 599, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bapat, A.; Salunkhe, P.B.; Patil, A.V. Hall-effect thrusters for deep-space missions: A review. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2022, 50, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.; Faraji, F.; Andreussi, T. Characterization of a high-power Hall thruster operation in direct-drive. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 178, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Cho, S.; Funaki, I.; Kusawake, H.; Kajiwara, K.; Kurokawa, F.; Takahashi, T. Control algorithm for a 6 kW hall thruster. J. Electr. Propuls. 2022, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanromán Reséndiz, M. Electric Design of the Power Processing Unit for Pulsed Plasma Thrusters for CubeSat Applications. Master’s Thesis, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzesh, M.; Siwakoti, Y.P.; Gorji, S.A.; Blaabjerg, F.; Lehman, B. Step-up DC–DC converters: A comprehensive review of voltage-boosting techniques, topologies, and applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 9143–9178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Vecchia, M.; Martinez, W.; Driesen, J. An overview of power conversion techniques and topologies for DC-DC voltage regulation. In Proceedings of the IECON 2020 the 46th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Singapore, 18–21 October 2020; pp. 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Massoud, A.M. State-of-the-art DC-DC converters for satellite applications: A comprehensive review. Aerospace 2025, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.W. Vacuum Stability Requirements of Polymeric Material for Spacecraft Application; Technical Memorandom; Johnson Space Center: Houston, TX, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- ECSS ECSS-Q-ST-70-02C; Space Product Assurance—Thermal Vacuum Outgassing Test for the Screening of Space Materials. ECSS Standard: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2008.

- ECSS ECSS-Q-ST-70-12C; Space Product Assurance—Measurement of Thermo-Optical Properties of Thermal Control Materials. ECSS Standard: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2023.

- ECSS ECSS-E-ST-10-12C; Space Engineering—Methods for the Calculation of Radiation Received and Its Effects, and a Policy for Design Margins. ECSS Standard: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2022.

- ECSS ECSS-E-ST-31C; Space Engineering—Thermal Control General Requirements. ECSS Standard: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2018.

- ECSS ECSS-E-ST-20-07; Space Engineering—Electromagnetic Compatibility. ECSS Standard: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2022.

- Conversano, R.W.; Barchowsky, A.; Vorperian, V.; Chaplin, V.H.; Becatti, G.; Carr, G.A.; Stell, C.B.; Loveland, J.A.; Goebel, D.M. Cathode & electromagnet qualification status and power processing unit development update for the ascendant sub-kW transcelestial electric propulsion system. In Proceedings of the Annual Small Satellite Conference, Logan, UT, USA, 1–6 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pinero, L.R.; Kamhawi, H.; Drummond, G. Integration testing of a modular discharge supply for NASA’s high voltage hall accelerator thruster. In Proceedings of the 31st International Electric Propulsion Conference (IEPC 2009), Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 20–24 September 2009; Number E-17195. Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, M.; Zhang, D.; Qi, X. A novel power processing unit (PPU) system architecture based on HFAC bus for electric propulsion spacecraft. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 5381–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinero, L.; Scheidegger, R.; Bozak, K.; Birchenough, A. Development of high-power hall thruster power processing units at NASA GRC. In Proceedings of the 51st AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 27–29 July 2015; p. 3921. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, P. Resonant power conversion: Insights from a lifetime of experience. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 9, 6561–6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddipadiga, B.P.R.; Prabhala, V.A.K.; Ferdowsi, M. A family of high-voltage-gain DC–DC converters based on a generalized structure. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 8399–8411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryaei, M.; Khajehoddin, S.A.; Mashreghi, J.; K. Afridi, K. A new approach to steady-state modeling, analysis, and design of power converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 12746–12768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H.; Laursen, J. Power Conditioning Unit for Rosetta/Mars Express. In Proceedings of the Sixth European Space Power Conference; Porto, Portugal, 6–10 May 2002, Wilson, A., Ed.; ESA Special Publication: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 502, p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaeiha, A.; Anbarloui, M.; Farshchi, M. Design, development and operation of a laboratory pulsed plasma thruster for the first time in west Asia. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. Aerosp. Technol. Jpn. 2011, 9, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomescu, B.; Clayton, P.; Staley, M.; Waranauskas, J.; Kendall, J.; Saghri, S.; Malone, S.; Delgado, J.; Nelson, N.; Esquivias, J. High Efficiency, Versatile Power Processing Units for Hall-Effect Plasma Thrusters. In Proceedings of the 2018 Joint Propulsion Conference, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 9–11 July 2018; p. 4642. [Google Scholar]

- Promislow, C.; Little, J. Operation and performance of a power processing unit for inductive pulsed plasma thrusters operating at high repetition rates. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2022, 50, 3065–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lan, J.; Chen, N.; Fang, T.; Ruan, X.; He, X. A novel two-stage DC/DC converter applied to power processing unit for astronautical ion propulsion system. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 13–15 February 2019; pp. 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.K.; Lai, Y.C.; Lu, W.C.; Lin, A. Design and implementation of high reliability electrical power system for 2U NutSat. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampelli, P.K.; Deekshit, R.; Reddy, D.S.; Singh, B.K.; Chippalkatti, V.; Kanthimathinathan, T. Multiple-output magnetic feedback forward converter with discrete PWM for space application. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES), Bengaluru, India, 16–19 December 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, G.J. Power Conversion and Scaling for Vanishingly Small Satellites with Electric Propulsion. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.; Low, K.S.; Soon, J.J.; Tran, Q.V. Single-switch quasi-resonant DC–DC converter for a pulsed plasma thruster of satellites. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 32, 4503–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.H.; Shin, G.S.; Nam, M.R.; Kang, K.I.; Lim, J.T. High voltage DC-DC converter of pulsed plasma thruster for science and technology satellite-2 (STSAT-2). In Proceedings of the 2005 International Conference on Power Electronics and Drives Systems, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 28 November–1 December 2005; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 926–931. [Google Scholar]

- Gollor, M.; Breier, K. Compact High Voltage Power Processing For Field Emission Electric Propulsion (FEEP). In Proceedings of the 29th International Electric Propulsion Conference, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA, 31 October–4 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X. Design and analysis of a novel coupled converter with high-voltage insulation protection in magnetic isolated way. IET Power Electron. 2021, 14, 1995–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Das, P.; Panda, S. High voltage high frequency resonant DC-DC converter for electric propulsion for micro and nanosatellites. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 36th International Telecommunications Energy Conference (INTELEC), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 28 September–2 October 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Scheidegger, R.J.; Santiago, W.; Bozak, K.E.; Piñero, L.R.; Birchenough, A.G. High Power Silicon Carbide (SiC) Power Processing Unit Development. In Proceedings of the Electrochemical Society (ECS) Meeting, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 11–15 October 2015; Number GRC-E-DAA-TN25100. Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mallmann, A.; Forrisi, F.; Mache, E.; Blaser, M.; Hall, K.W. High Voltage Power Supply for T5 Gridded Ion Thruster. In Proceedings of the 36th International Electric Propulsion Conference, IEPC-2019A512, Vienna, Austria, 15–20 September 2019; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Watanabe, H.; Goto, D.; Cho, S.; Kusawake, H.; Kurokawa, F.; Kajiwara, K.; Funaki, I. Wide-output range power processing unit for 6-kW hall thruster. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 58, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peng, Z.; Song, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, H. Ion Electric Propulsion System Design Considerations for Beam Sparkle. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 15572–15581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, S.; Aghazadeh, F.; Lenguito, G.; Staley, M.; Kerl, T.; Tomescu, B.; Snyder, J.S. Deep space power processing unit for the psyche Mission. In Proceedings of the 36th International Electric Propulsion Conference, Vienna, Austria, 15–20 September 2019; Electric Rocket Propulsion Society: Brook Park, OH, USA, 2019; pp. 2019–2280. [Google Scholar]

- Pinero, L.R.; Bond, T.H.; Okada, D.; Phelps, K.; Pyter, J.; Wiseman, S. Modular 5-kW power-processing unit being developed for the next-generation ion engine. In Research and Technology 2000; Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bekemans, M.; Bronchart, F.; Scalais, T.; Franke, A. Configurable high voltage power supply for full electric propulsion spacecraft. In Proceedings of the 2019 European Space Power Conference (ESPC), Juan-les-Pins, France, 30 September–4 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, D.A.; Santiago, W.; Kamhawi, H.; Polk, J.E.; Snyder, J.S.; Hofer, R.R.; Parker, J.M. The Ion propulsion system for the solar electric propulsion technology demonstration mission. In Proceedings of the Nano-Satellite Symposium (NSAT), Kobe-Hyogo, Japan, 4–10 July 2015; Number IEPC-2015-008/ISTS-2015-b-008. Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, H.; Kurokawa, F. Evaluation of LLC resonant converter in anode power supply for all-electric satellites. In Proceedings of the 2020 9th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Application (ICRERA), Glasgow, UK, 27–30 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 414–417. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, W.; Peng, L.; Zheng, L. Development of a Three-Phase LCC Resonant Converter with a High-Voltage Rise Ratio for the Power Processing Unit. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Energy, Power and Electrical Engineering (EPEE), Wuhan, China, 15–17 September 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 682–686. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Tong, C.; Wang, Z. Normalized analysis and optimal design of DCM-LCC resonant converter for high-voltage power supply. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 4496–4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, M.; Lee, B.; Lai, J. Analysis and design of LLC converter considering output voltage regulation under no-load condition. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Sequential offline-online-offline measurement approach for high-frequency LCLC resonant converters in the TWTA applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 1568–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, X. An efficiency-oriented two-stage optimal design methodology of high-frequency LCLC resonant converters for space travelling-wave tube amplifier applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Xin, X.; Wang, R.; Dong, M.; Lin, J.; Gu, Y.; Li, H. A 1-MHz GaN-based LCLC resonant step-up converter with air-core transformer for satellite electric propulsion application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 11035–11045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jing, J.; Guan, Y.; Dai, M.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D. High-efficiency high-order CL-LLC DC/DC converter with wide input voltage range. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 10383–10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Ruan, X. Equivalence relations of resonant tanks: A new perspective for selection and design of resonant converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 2111–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshsaadat, A.; Moghani, J.S. Fifth-order T-type passive resonant tanks tailored for constant current resonant converters. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2018, 65, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.-Y.; Chen, R.; Viswanathan, A. Survey of Resonant Converter Topologies; Technical Report; Texas Instruments: Dallas, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Outeiro, M.T.; Buja, G.; Czarkowski, D. Resonant power converters: An overview with multiple elements in the resonant tank network. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2016, 10, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Zhang, D.; Li, T. New electrical power supply system for all-electric propulsion spacecraft. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2017, 53, 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, O.; Alekseenko, O.; Tolmachov, V. Power Processing and control unit of the electric propulsion system. J. Rocket-Space Technol. 2023, 32, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmol, A.; Zamiri, E.; Purraji, M.; Murillo, D.; Díaz, J.T.; Vazquez, A.; de Castro, A. Dual control strategy for non-minimum phase behavior mitigation in DC-DC boost converters using finite control set model predictive control and proportional–integral controllers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfi, G.; Beik, O. MW-scale high-voltage direct-current power conversion for large-spacecraft electric propulsion. Electronics 2024, 13, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhu, J.; Dai, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Xu, Q.; Ning, Y.; He, S. Lightweight Design of Magnetic Integrated Transformer for High Voltage Power Supply in Electro-aerodynamic Propulsion System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 10501–10515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramraju, K.J.; Eisen, J.; Rovey, J.L.; Kimball, J.W. A New Discontinuous Conduction Mode in a Transformer Coupled High Gain DC-DC Converter. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Houston, TX, USA, 20–24 March 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Santoja, A.; Barrado, A.; Fernandez, C.; Sanz, M.; Raga, C.; Lazaro, A. High voltage gain DC-DC converter for micro and nanosatellite electric thrusters. In Proceedings of the 2013 Twenty-Eighth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Long Beach, CA, USA, 17–21 March 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 2057–2063. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Das, P.; Panda, S. Analysis, design and implementation of quadrupler based high voltage full bridge series resonant DC-DC converter. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 14–18 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 4059–4064. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.; Low, K.S. A single-switch high voltage quasi-resonant DC-DC converter for a pulsed plasma thruster. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 11th International Conference on Power Electronics and Drive Systems, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 9–12 June 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 509–513. [Google Scholar]

- Katzir, L.; Shmilovitz, D. A matrix-like topology for high-voltage generation. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2015, 43, 3681–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzir, L.; Shmilovitz, D. A 1-MHz 5-kV power supply applying SiC diodes and GaN HEMT cascode MOSFETs in soft switching. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2016, 4, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddipadiga, B.P.; Strathman, S.; Ferdowsi, M.; Kimball, J.W. A high-voltage-gain DC-DC converter for powering a multi-mode monopropellant-electrospray propulsion system in satellites. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 4–8 March 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1561–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Quraan, M.; Zahran, A.; Herzallah, A.; Ahmad, A. Design and model of series-connected high-voltage DC multipliers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 7160–7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yang, J.; Rivas-Davila, J. A hybrid Cockcroft-Walton/Dickson multiplier for high voltage generation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 2714–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Emamalipour, R.; Cheema, M.A.M.; Lam, J. A constant frequency step-up resonant converter with a re-structural feature and a PWM-controlled voltage multiplier. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 14–17 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Perreault, D.J. Lightweight high-voltage power converters for electroaerodynamic propulsion. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 2021, 2, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; An, J.; Wan, C.A. Space High-Voltage Power Module. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 642920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, A.; Dworski, S.; Ma, C.; Ryan, C.; Ferreri, A.; Vincent, G.; Larsen, H.; Azevedo, E.R.; Dingle, E.; Garbayo, A.; et al. Development of Porous Emitter Electrospray Thruster Using Advanced Manufacturing Processes. In Proceedings of the International Electric Propulsion Conference, Cambridge, MA, USA, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ouhammam, A.; Mahmoudi, H.; Ouadi, H. Design and control of high voltage gain DC–DC converter for CubeSat propulsion. CEAS Space J. 2024, 16, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Gong, J.; Zhao, X.; Yeh, C.; Lai, J. Analysis of diode reverse recovery effect on ZVS condition for GaN-based LLC resonant converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 11952–11963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, B.; Gao, J.; Chi, K.T.; Xu, L. Effects of Nonlinear Junction Capacitance of Rectifiers on Performance of High Voltage Power Supplies. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 15693–15706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramraju, K.J.P.; Kimball, J.W. An improved power processing unit for multi-mode monopropellant electrospray thrusters for satellite propulsion systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Baltimore, MD, USA, 29 September–3 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1302–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.; Low, K.S.; Ng, K.J. Capacitor Charging by Quasi-Resonant Approach for a Pulsed Plasma Thruster in Nano-Satellite. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2020, 48, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coday, S.; Barchowsky, A.; Pilawa-Podgurski, R.C. A 10-level gan-based flying capacitor multilevel boost converter for radiation-hardened operation in space applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 14–17 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 2798–2803. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoua Teu Magambo, J.S.; Bakri, R.; Margueron, X.; Le Moigne, P.; Mahe, A.; Guguen, S.; Bensalah, T. Planar Magnetic Components in More Electric Aircraft: Review of Technology and Key parameters for DC–DC power electronic converter. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2017, 3, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Andersen, M.A.E. Overview of planar magnetic technology—Fundamental properties. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 4888–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.C.; Li, Q.; Nabih, A. High frequency resonant converters: An overview on the magnetic design and control methods. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 9, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, J.; Godignon, P.; Perpiñá, X.; Pérez-Tomás, A.; Rebollo, J. A survey of wide bandgap power semiconductor devices. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 2155–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafin, S.S.H.; Ahmed, R.; Haque, M.A.; Hossain, M.K.; Haque, M.A.; Mohammed, O.A. Power Electronics Revolutionized: A Comprehensive Analysis of Emerging Wide and Ultrawide Bandgap Devices. Micromachines 2023, 14, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Williford, P.R.; Jones, E.A.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Bala, S.; Xu, J. Factors and considerations for modeling loss of a GaN-based inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 3042–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Li, H.; Yin, S.; Wu, Y.; See, K.Y. A postprocessing-technique-based switching loss estimation method for GaN devices. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 8253–8266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.A.; Wang, F.F.; Costinett, D. Review of commercial GaN power devices and GaN-based converter design challenges. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2016, 4, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchowsky, A.; Kozak, J.P.; Grainger, B.M.; Stanchina, W.E.; Reed, G.F. A GaN-based modular multilevel DC-DC converter for high-density anode discharge power modules. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 4–11 March 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Conversano, R.W.; Barchowsky, A.; Lobbia, R.B.; Chaplin, V.H.; Lopez Ortega, A.; Loveland, J.A.; Lui, A.D.; Becatti, G.; Reilly, S.W.; Goebel, D.; et al. Overview of the ascendant sub-kw transcelestial electric propulsion system (astraeus). In Proceedings of the 36th International Electric Propulsion Conference, Vienna, Austria, 15–20 September 2019; pp. 2019–2282. [Google Scholar]

- Boomer, K.; Scheick, L.; Hammoud, A. Body of Knowledge (BOK): Gallium Nitride (GaN) Power Electronics for Space Applications. In Proceedings of the NASA Electronic Parts and Packaging Program Electronics Technology Workshop, Greenbelt, MD, USA, 17–20 June 2019; Number GRC-E-DAA-TN70017. Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, C.; Lai, J.; Yu, O. Circuit design considerations for reducing parasitic effects on GaN-based 1-MHz high-power-density high-step-up/down isolated resonant converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2019, 7, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.; Grainger, B.; Amirahmadi, A.; Barchowsky, A.; Stell, C. Soft-Switching GaN-Based Isolated Power Conversion System for Small Satellites with Wide Input Voltage Range. In Proceedings of the Annual Small Satellite Conference, Logan, UT, USA, 1–6 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Minghai, D.; Shan, Y.; Yingzhe, W.; Hui, L. Performance Evaluation of 40-V/10-A GaN HEMT Versus Si MOSFET for Low-Voltage Buck Converter Application. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 9th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (IPEMC2020-ECCE Asia), Nanjing, China, 29 November–2 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 3428–3435. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, W.; Zhang, F.; Dong, G.; Wu, J.; Li, L. Research on losses of PCB parasitic capacitance for GaN-based full bridge converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 4287–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, B.; McPherson, B.; Schupbach, M.; Lostetter, A. Silicon carbide power processing unit for Hall effect thrusters. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 3–10 March 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhou, W.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; You, C. Analytical Switching Model of a 1200V SiC MOSFET in a High-voltage, High-frequency Pulsed Power Converter for Plasma Generation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Baltimore, MD, USA, 29 September–3 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1911–1917. [Google Scholar]

- Piñero, L.R.; Scheidegger, R.J.; Aulsio, M.V.; Birchenough, A.G. High input voltage discharge supply for high power hall thrusters using silicon carbide devices. In Proceedings of the International Electric Propulsion Conference (IEPC2013), Washington, DC, USA, 6–10 October 2013; Number NASA/TM-2014-216607. Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ikpe, S.A.; Lauenstein, J.M.; Carr, G.A.; Hunter, D.; Ludwig, L.L.; Wood, W.; Iannello, C.J.; Del Castillo, L.Y.; Fitzpatrick, F.D.; Mojarradi, M.M.; et al. Long-term reliability of a hard-switched boost power processing unit utilizing SiC power MOSFETs. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Pasadena, CA, USA, 17–21 April 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; p. ES–1. [Google Scholar]

- Boomer, K.; Lauenstein, J.M.; Hammoud, A. Body of Knowledge for Silicon Carbide Power Electronics; Technical Report; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jayant Baliga, B. Silicon Carbide power devices: Progress and future outlook. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 2400–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wong, T.T.Y.; Shen, Z.J. A survey on switching oscillations in power converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2019, 8, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Li, H.; Yin, S.; See, K.Y.; Wu, Y.; Xin, X. Mitigation of Deane and Hamill phenomenon in gallium nitride high-voltage power supply for electric propulsion system application. High Volt. 2023, 9, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Li, H.; Zhong, Q.; Wu, Y. Common mode noise analysis of buck-boost converter for hybrid energy storage systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility and 2018 IEEE Asia-Pacific Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC/APEMC), Suntec City, Singapore, 14–18 May 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1013–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Coletti, M.; Ciaralli, S.; Gabriel, S.B. PPT development for nanosatellite applications: Experimental results. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2014, 43, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Li, H.; Yin, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y. Common-mode noise analysis and suppression of a GaN-based LCLC resonant converter for ion propulsion power supply. In Proceedings of the 2021 Asia-Pacific International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (APEMC), Nusa Dua-Bali, Indonesia, 27–30 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M.; Li, H.; See, K.Y.; Yin, S.; Zhao, Z.; Fan, F.; Wu, Y. Comparison Study on EMI Performance of SiC and Si diodes in Cockcroft-Walton Voltage Multiplier. In Proceedings of the 2022 Asia-Pacific International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (APEMC), Beijing, China, 1–4 September 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 694–697. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Who | What |

|---|---|---|

| 1906 | Robert Goddard | Hand-written notes on EP |

| 1911 | Konstantin Tsiolkowsky | Published EP concept |

| 1929 | Hermann Oberth | Full chapter on EP in |

| 1951 | Lyman Spitzer | Demonstration of feasibility of EP |

| 1954 | Ernst Stuhlinger | In-depth analysis of EP system |

| 1964 | US, USSR | Successful use of EP in space (Zond-2, SERT-1) |

| 1980s | US, USSR | Commercial use of resistojets and Hall thrusters on GEO platforms (Intelsat-V 2) |

| 1998 | US | Deep-space probe with EP (Deep Space 1) |

| 2000s | Europe | Transfer to the moon (Smart-1), Earth gravity field measurement (GOCE) |

| 2010s | US, Europe | All-electric platform reaches GEO (Boing 702SP, Eurostar E3000EOR) |

| 2018 | Europe | Mercury’s mission BepiColombo |

| EP Type | Core Power Supply Requirements | Key Converter Design Constraints | Space-Specific Standards Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|

| HET | Anode: 1∼3 kV, 0.1∼1 A; Magnet: 28 V, 5∼20 A | High efficiency; SEE mitigation; vacuum thermal management | ECSS-E-ST-10-12C (radiation); ECSS-Q-ST-70-02C (outgassing) |

| Ion thruster | Anode: 1∼5 kV, 10∼100 mA; Grid: 0.5∼2 kV | Ultra-low ripple; low-outgassing components; high-voltage regulation | ECSS-E-ST-10-12C; ECSS-Q-ST-70-02C |

| PPT | Discharge: 24∼48 V, 100∼500 A (pulses) | Fast dynamic response; compact design; vacuum creepage/clearance ≥ 3 mm/kV | ECSS-E-ST-20-06C (components); ECSS-Q-30-11A (derating) |

| FEEP | Emitter: 10∼30 kV, 1∼10 A | Ultra-high-voltage stability; low-outgassing; radiation-tolerant control ICs | ECSS-Q-ST-70-02C; ECSS-E-ST-10-12C |

| Resistojet | Heater: 28∼100 V, 10∼50 A | High current handling; thermal cycling tolerance; EMI suppression | ECSS-E-ST-20-07 (EMI); ECSS-E-ST-31C (thermal control) |

| Topology | Merits | Drawbacks | Power Level (W) |

|---|---|---|---|

| buck | simple, high efficiency, low output ripple | limited step-down capability | 1∼ |

| boost | simple, high efficiency | limited step-up capability, challenged voltage regulation | 1∼ |

| buck–boost | flexible voltage conversion, simple, high efficiency | complex, sensitive to load variations. | 1∼ |

| Cuk | flexible voltage conversion, low ripple, voltage inversion capability | complex, limited by duty cycle | 10∼ |

| SEPIC | non-inverting voltage conversion, wide input voltage range, continuous input and output currents | complex, lower efficiency, sensitive to component tolerances | 1∼ |

| Zeta | non-inverting voltage conversion, higher efficiency, reduced ripple | limited by duty cycle, limited availability of integrated circuits | 1∼ |

| Topology | Merits | Drawbacks | Power Level (W) |

|---|---|---|---|

| forward | simple, good efficiency, low cost, high reliability | low transformer utilization factor, limited voltage capability | ∼ |

| flyback | simple, low cost, high reliability | low transformer utilization factor, limited voltage capability, higher output ripple voltage | 10∼ |

| push–pull | simple, good efficiency, low cost, high reliability, reduced voltage stress on components | balancing issue, complex control requirements | ∼ |

| half-bridge | low cost, good efficiency, lower voltage stress, high low transformer utilization factor | low reliability, careful consideration of dead-time management, complex driven circuit | ∼ |

| full-bridge | high low transformer utilization factor, reduced output ripple, flexibility in control, suitable for high-frequency operation, resilience to load variations | high cost, low reliability, complex driven circuit, complex control requirements, higher EMI, high voltage stress on components | ∼ |

| EP Type | Power-Level Requirement | Recommended Converter Topologies | Key Focus for Future Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| HET | Medium–high power | isolated full-bridge; ; DDA | Optimize WBG-compatible topologies; integrate planar magnetics; develop DDA-specific fault-tolerant control algorithms |

| Ion thruster | Medium power | forward/flyback; high-order resonant converter ; Voltage multiplier | Wide input voltage adaptation design; radiation-hardened control ICs; active EMI suppression technology |

| PPT | Pulsed high power | boost; quasi-resonant; bidirectional DAB | Optimize pulse current rising edge control; SEB protection for SiC devices; integrated pulsed energy storage modules |

| FEEP | Micro-power | flyback; Dickson voltage multiplier; soft-switching quasi-resonant | Application of miniaturized planar magnetics; high-voltage breakdown protection design; low-power radiation-hardened drive circuits |

| Resistojet | Low–medium power | buck-boost; interleaved boost; voltage-fed converter | Optimization of multi-phase interleaved topologies; high-temperature stable magnetic materials; efficient passive heat dissipation structures |

| Arcjet | Medium power | SEPIC; Soft-switching ZVS boost; modular multilevel converter | Replacement of silicon devices with WBG devices; application of magnetic integration technology; standardized EMC filter modules |

| MPDT | High power | isolated full-bridge; current-fed; multi-module cascaded | Development of high-power DDA architecture; integrated liquid cooling; adaptive compensation algorithms for radiation-induced parameter drift |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, M.; Li, H.; Yin, S.; Tian, B.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y. An Overview of DC-DC Power Converters for Electric Propulsion. Aerospace 2026, 13, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010036

Dong M, Li H, Yin S, Tian B, Yang S, Chen Y. An Overview of DC-DC Power Converters for Electric Propulsion. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Minghai, Hui Li, Shan Yin, Bin Tian, Sulan Yang, and Yuhua Chen. 2026. "An Overview of DC-DC Power Converters for Electric Propulsion" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010036

APA StyleDong, M., Li, H., Yin, S., Tian, B., Yang, S., & Chen, Y. (2026). An Overview of DC-DC Power Converters for Electric Propulsion. Aerospace, 13(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010036