4.1. Damage Prediction Using Temperature- and Pyrolysis-Based Models

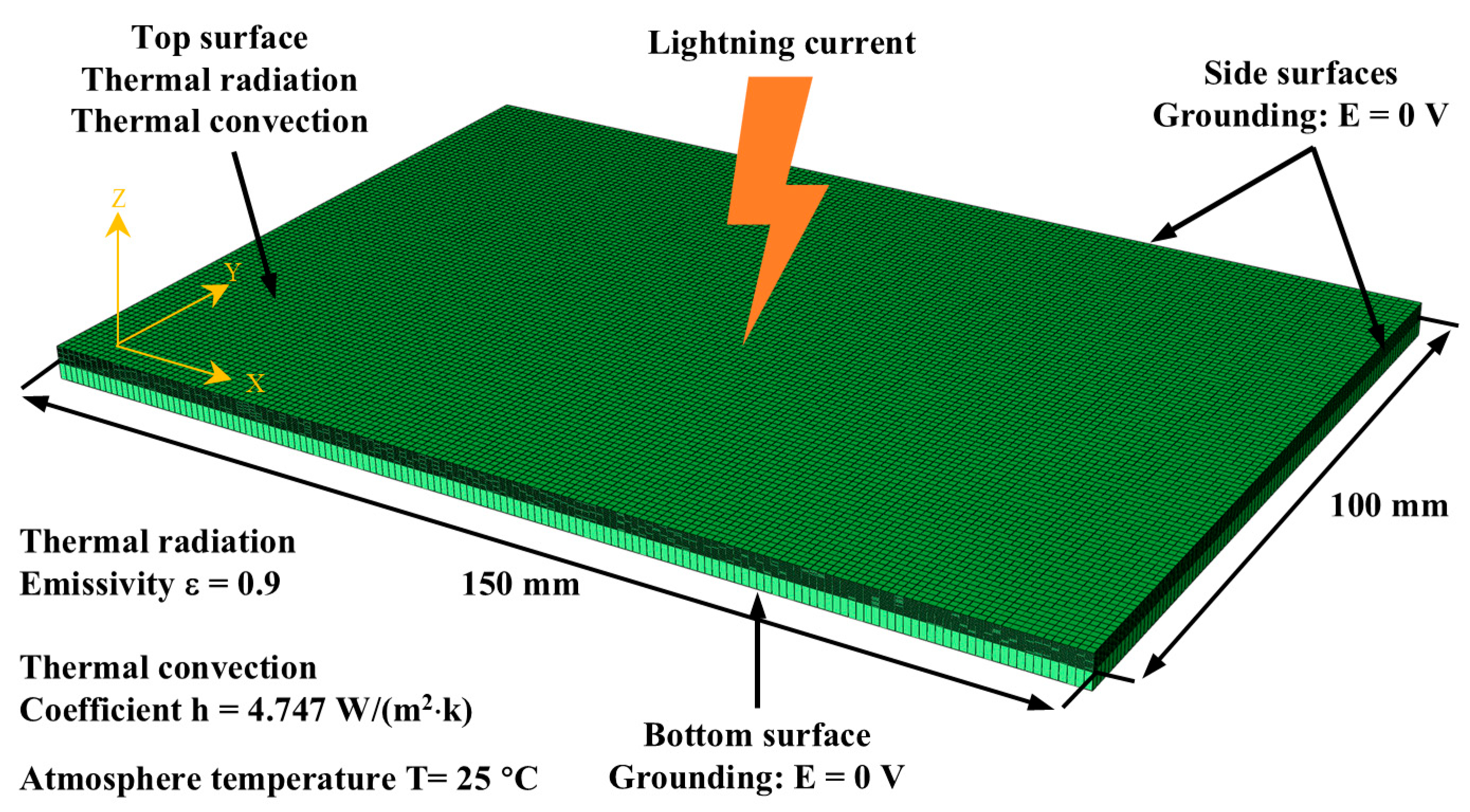

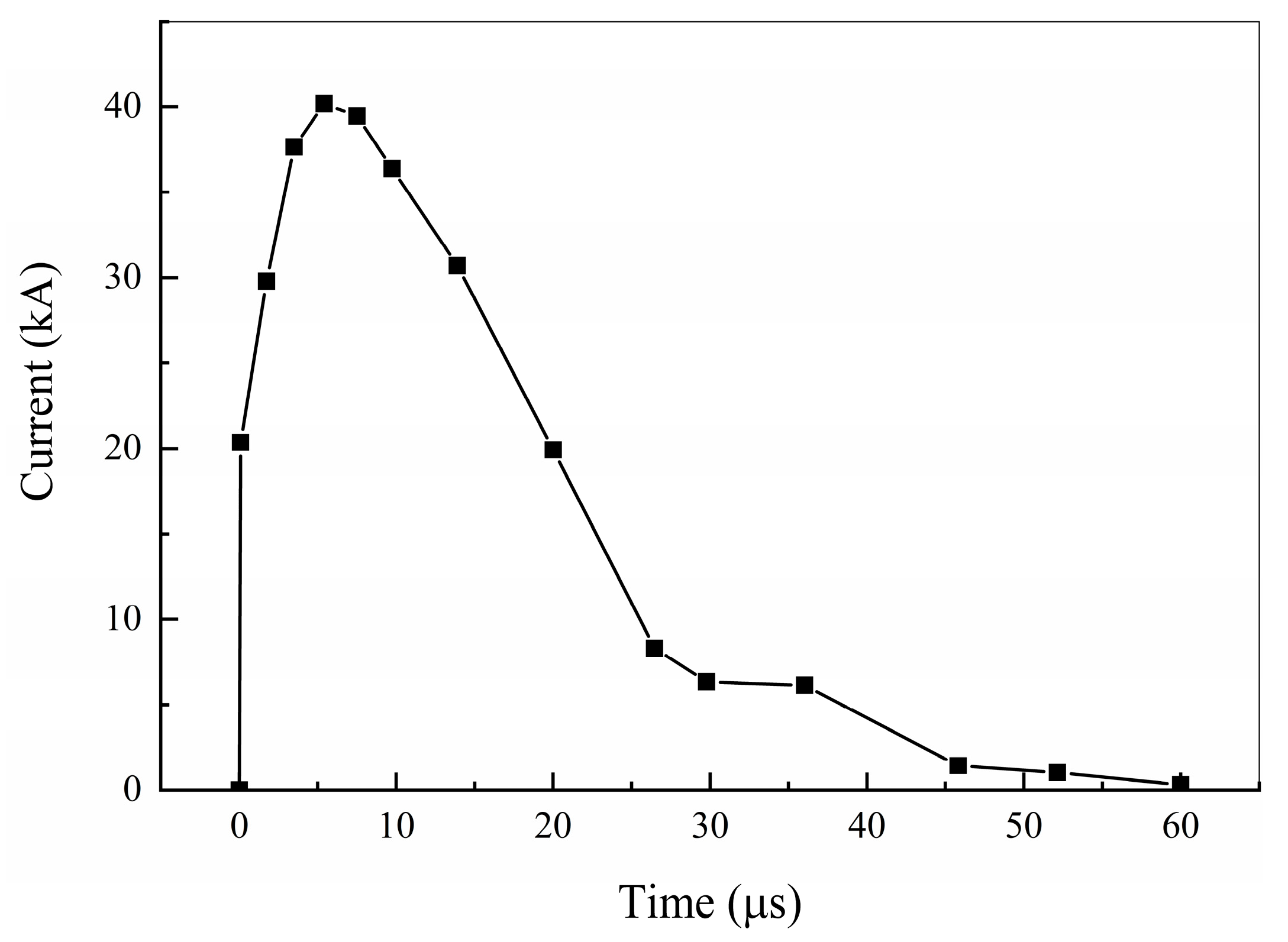

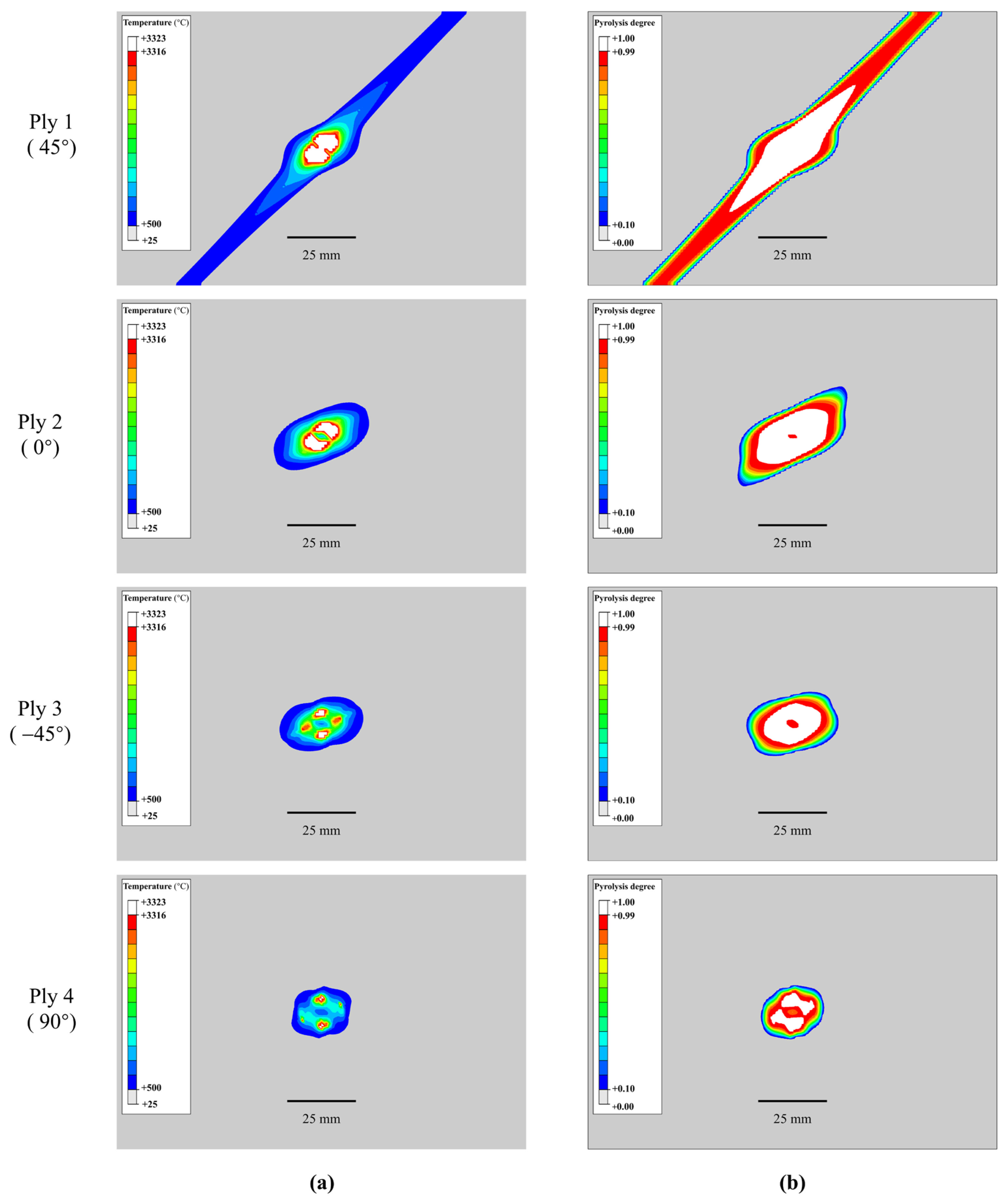

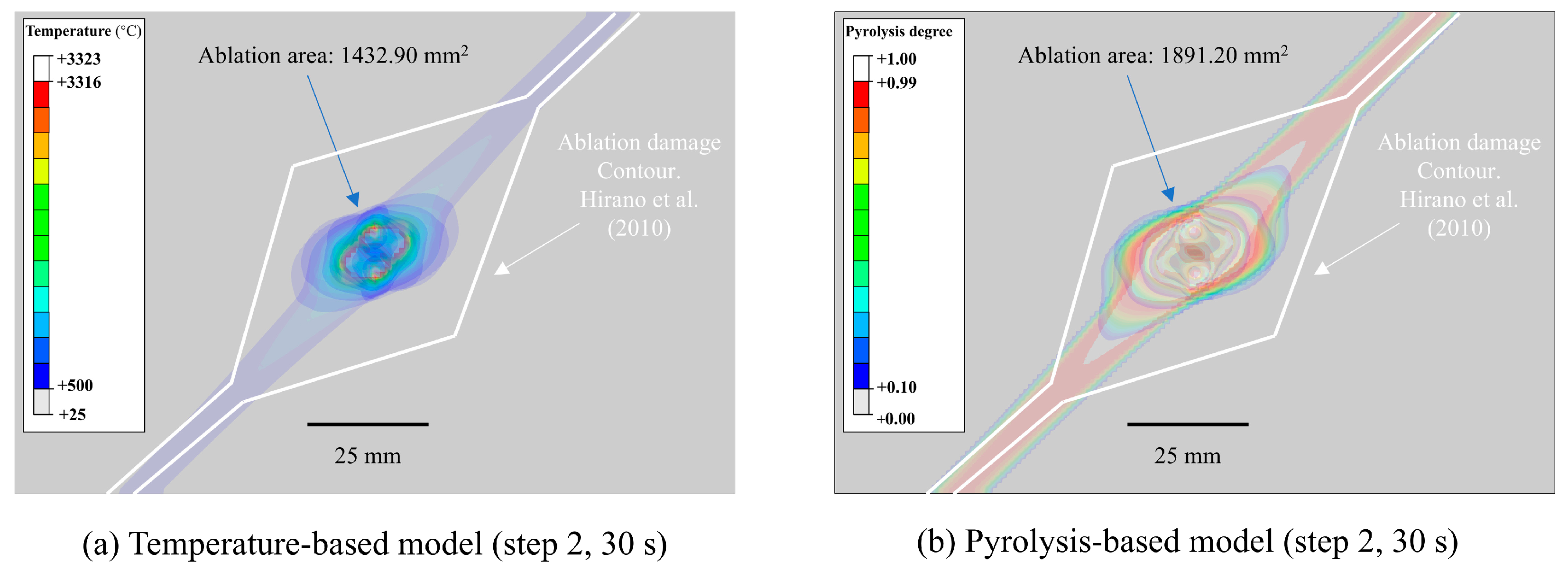

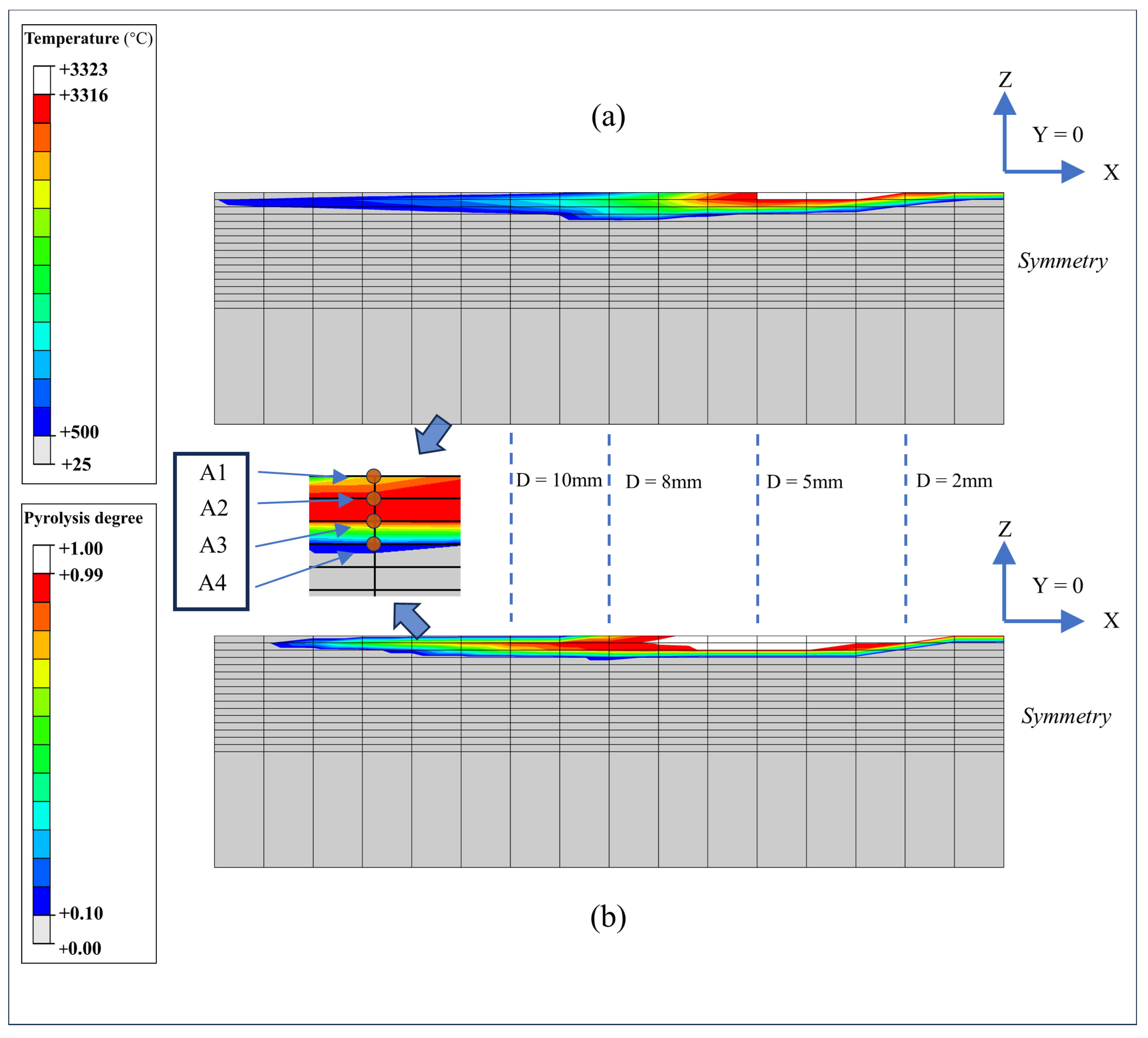

Contour plots of temperature and pyrolysis filed at 30 s of step 2 were depicted in

Figure 4. For the temperature-based model, the white area around the center of the sample indicates a temperature above 3316 °C and the grey area below 500 °C. These two thresholds correspond to the resin decomposition temperature and fibre sublimation temperature [

16,

25]. For the pyrolysis-based model, the white area around the center of the laminated composite panel indicates a pyrolysis degree greater than 0.99 and the grey area under 0.1. In the pyrolysis-based model, 0.1 was used to represent the beginning of pyrolysis [

24,

41]. The damage profile of these two models was overall consistent. In each single layer of laminated composite, lightning strike damage extends along the fiber direction, but was also affected by adjacent layers. The damage footprint of the temperature- and pyrolysis-based model was shown in

Figure 5. The simulation results of both models exhibited consistent damage distribution characteristics with the experimental data, as both demonstrated primary damage propagation along the 45° fiber direction in the first ply [

4]. The temperature-based model predicted an ablation damage area of 1432.90 mm

2, while the pyrolysis-based model yielded a prediction of 1891.20 mm

2. The experimental measurements showed an average ablation damage footprint of approximately 1865.56 mm

2 and an average delamination damage footprint of approximately 2009.30 mm

2 [

4]. The temperature-based model predicted an ablation area with an error of −23.2% compared to the experimental results, whereas the pyrolysis-based model showed an error of +1.4%. The research results indicate that the damage area predicted by the temperature-based model is smaller than that predicted by the pyrolysis-based model, which may be related to the selection of the temperature threshold value. Considering moisture vaporization occurs at 300 °C, Foster et al. [

25] also adopted 300 °C to evaluate the lightning strike damage of composites. Using 300 °C as the damage threshold, the predicted damage area based on the temperature model reached 2591.20 mm

2, which is significantly larger than the current prediction based on 500 °C and even exceeds the experimental observations. However, the physical significance of using 300 °C to evaluate damage is still unclear, as the main damage modes in the experiment were fibre fracture, resin ablation, and delamination. Obviously, by adjusting the temperature threshold value between 300 °C and 500 °C, the temperature-based model can obtain an ablation area close to the experimental results. In fact, temperature thresholds of 300 °C [

16,

27,

36,

40], 343 °C [

42], 450 °C [

6], and even 800 °C [

25,

28] have also been used to evaluate composite material lightning strike damage. Temperature is a reversible physical quantity; the intrinsic correlation mechanism between material damage state and temperature value has not been fully understood. This is a scientific issue that requires further exploration in this field. In the next section, we will analyze the selection of damage thresholds for the temperature-based model and the pyrolysis-based model to form a more sufficient understanding of these two numerical models.

The temperature-based model ablated nine layers, reaching about 1.323 mm, while the pyrolysis-based model ablated eight layers, reaching about 1.176 mm, as listed in

Table 2. Compared to the experimental results [

2], the temperature-based and pyrolysis-based models exhibited errors of +13.7% and +1.0%. From a damage tolerance perspective, precise prediction of damage depth is critical, as lightning-induced damage in carbon fiber composites primarily manifests as surface-level degradation within laminated panels. In the numerical simulation model, based on the fundamental assumption that lightning-induced damage is predominantly confined to surface plies, a single element was used in the thickness direction to simulate the bottom 16 layers. The simulation results demonstrate that for both temperature-based and pyrolysis-based models, the maximum damage depth consistently remained within 10 plies. Due to the low conductivity in the thickness direction of undamaged composite materials, there is almost no current flowing through the bottom 16 layers. Therefore, this simplification is appropriate and will not have a significant impact on the simulation results.

Previous studies had suggested that pyrolysis-based model severely underestimate lightning damage [

17], using a pyrolysis-based model cannot effectively characterize the mechanism of lightning strike damage in composite materials [

36]. One important reason may be that Guo et al. [

36] used a temperature threshold of 300 °C to evaluate in-plane damage, which also resulted in their predicted damage depth being significantly greater than the experimental results. Additionally, a pyrolysis degree threshold of 0.5 was used to assess damage in the pyrolysis-based model, which also leads to a significant underestimation of the in-plane damage area. The results indicate that, for this specific experimental configuration and with the chosen parameters, the pyrolysis-based model shows closer agreement with the measured damage area and depth compared to the temperature-based model. This study also highlights that the predictive accuracy of temperature-based models is highly sensitive to the choice of damage threshold, as evidenced by the substantial variation in predicted damage area when using thresholds of 300 °C versus 500 °C.

4.2. Damage Threshold of Temperature- and Pyrolysis-Based Models

As noted in the previous section, existing temperature-based models have failed to establish a consensus on the determination of temperature thresholds, often rendering the selection process somewhat arbitrary. Temperature, as a physical parameter, is not a direct measure of heat-induced material damage but rather serves as a practical engineering indicator. The degree of pyrolysis is defined as the proportion of a material that undergoes decomposition or transformation during the pyrolysis process. Therefore, employing the degree of pyrolysis to evaluate the ablation damage of materials holds greater practical significance. Kamiyama et al. [

24] conducted heating experiments on carbon fiber composite laminates. The results indicated that significant delamination occurs when the degree of pyrolysis reaches 0.1. Adopting a pyrolysis degree threshold of 0.1 to evaluate the ablation damage of the laminates is justified. Therefore, this section focuses on the correspondence between different temperature thresholds and the pyrolysis degree of 0.1.

It is reasonable to use damage area and damage depth to evaluate the differences between temperature- and pyrolysis-based models, but these indicators do not truly reflect the inherent differences between these two models. The temperature of a material is related to its internal energy, while the pyrolysis degree of a material is a function of temperature, time, and heating rate. The temperature-based model cannot effectively consider the effect of heating rate on thermal damage, and empirical values of 300 °C [

16] or 500 °C [

25] were used. Therefore, authors analyzed the differences in lightning strike damage at heating rates of 10,000 °C/min, 15,000 °C/min, and 20,000 °C/min [

28]. However, the actual heating rate of composite materials in lightning strike simulation was much higher than these, which can be validated by the experiment [

5]. Take the 1600 °C as an example, under the load of lightning current, assuming that the material linearly heats up from 25 °C to 1600 °C within 400 μs, with an average heating rate of up to

°C/min. In the numerical simulation model, step 1 represents the heating process of current conduction, while step 2 represents the heat dissipation process after the end of current conduction. In order to analyze the inherent differences between temperature- and pyrolysis-based models, the commonly used temperature thresholds (300 °C, 500 °C, 800 °C, 1000 °C, and 3000 °C) for temperature-based models were selected as a reference to calculate material heating rates in step 1.

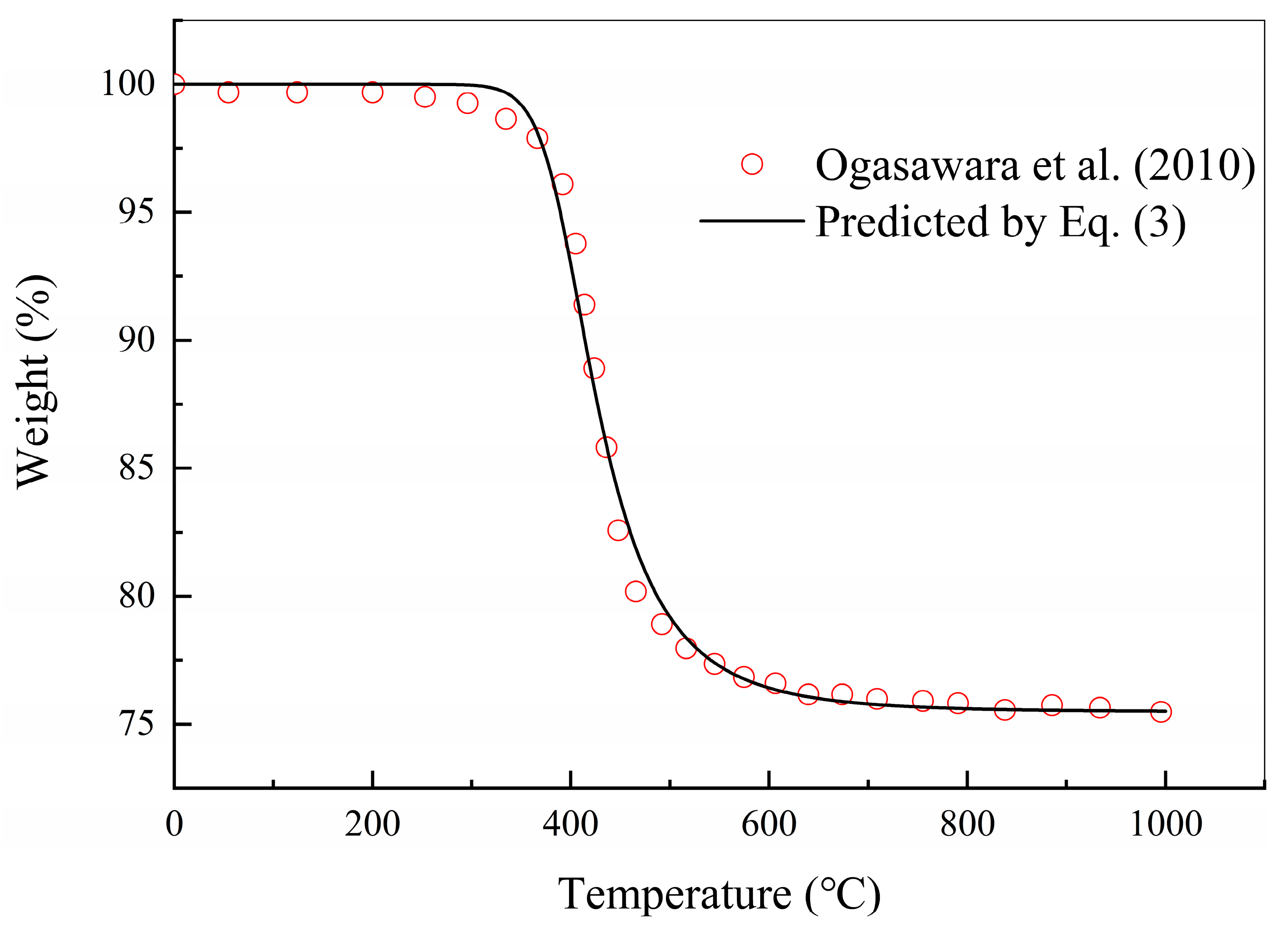

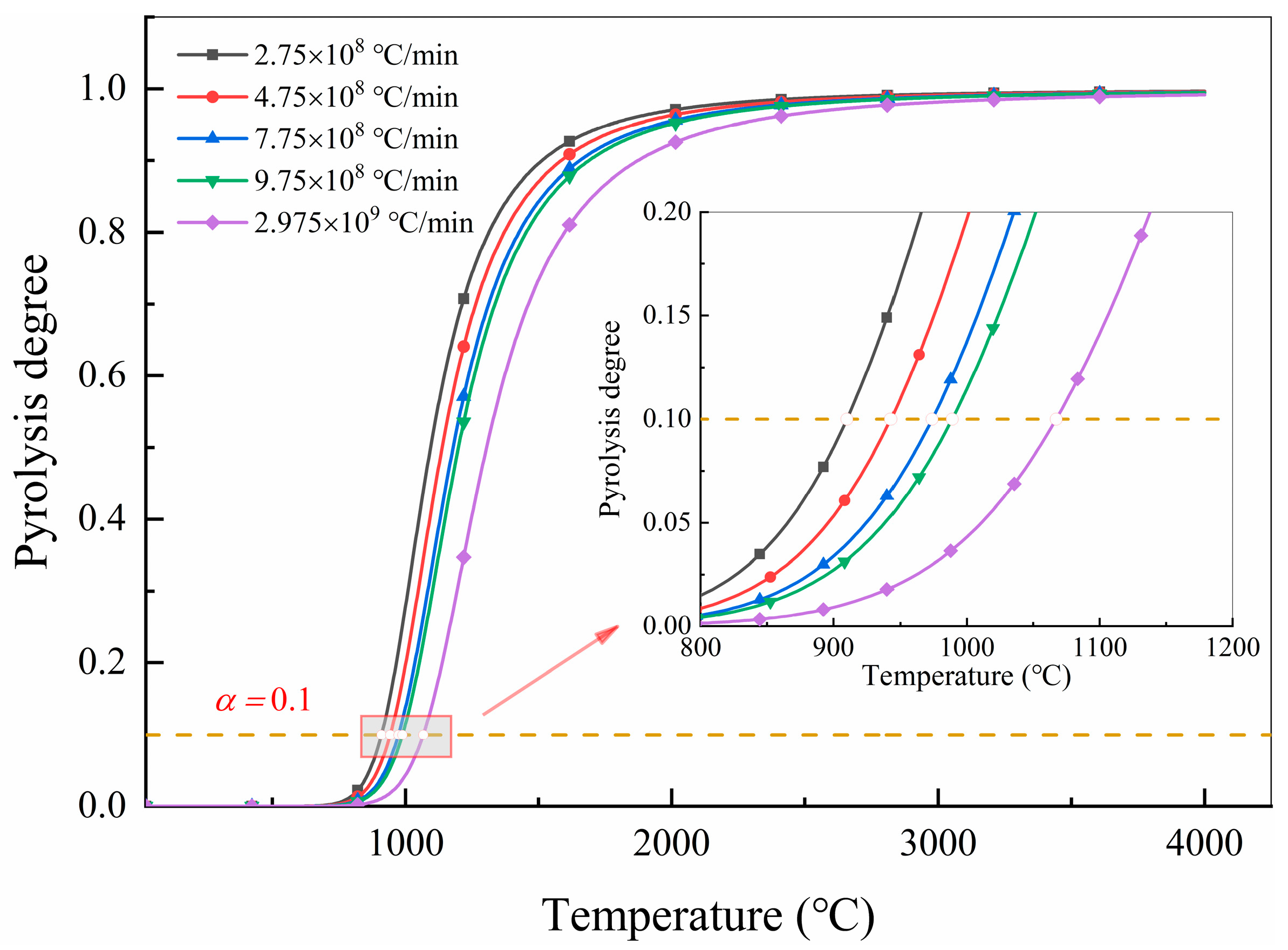

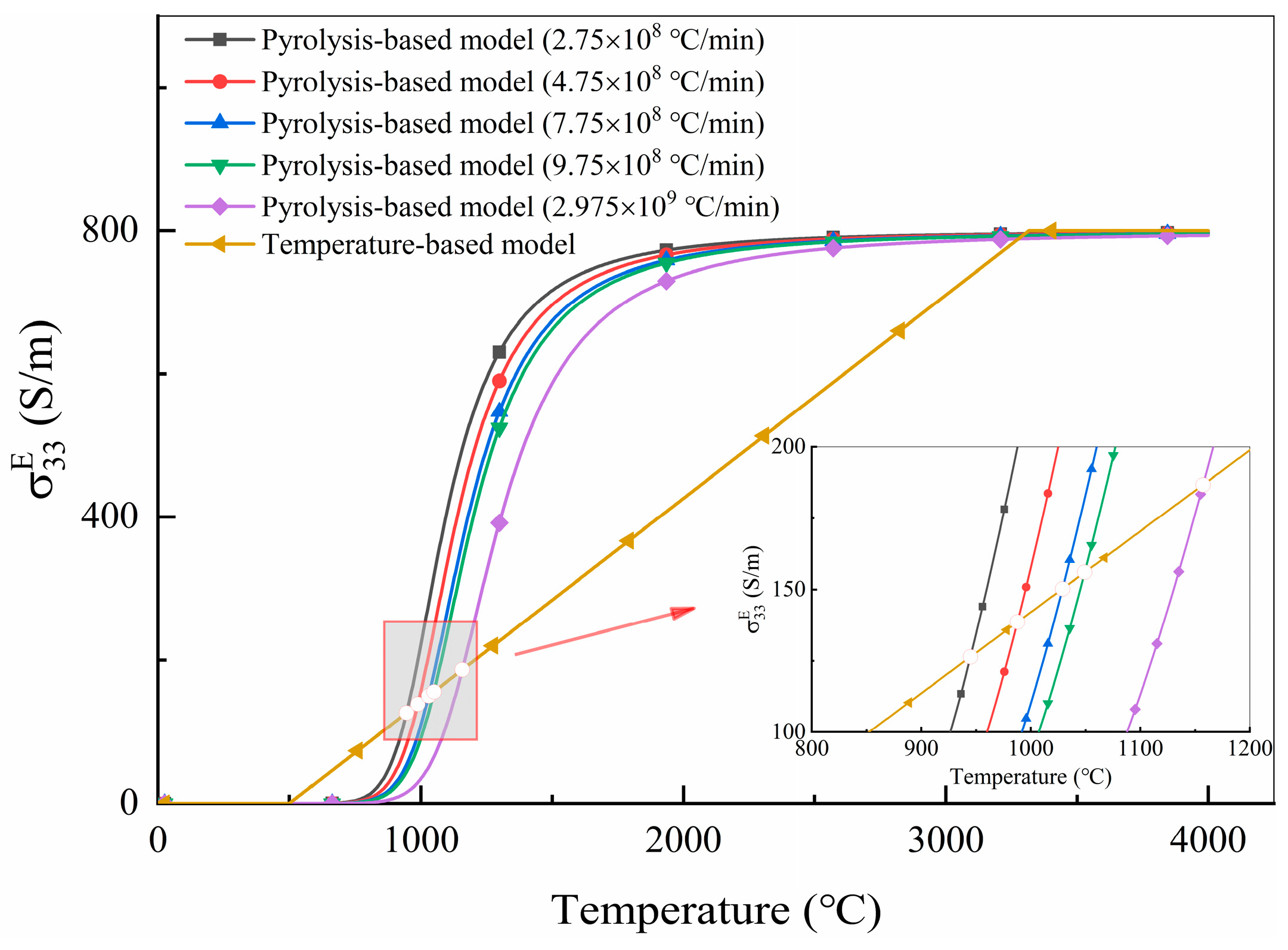

Based on the assumption of linear heating, pyrolysis kinetics analysis was conducted to obtain the pyrolysis degree-temperature curves of composite materials at different heating rates, as shown in

Figure 6. As the heating rate increases, the pyrolysis curve gradually shifted toward the high-temperature region. The abscissa of the intersection points between the pyrolysis degree of 0.1 and the pyrolysis degree-temperature curves at different heating rates means that the pyrolysis degree of the material reaches 0.1 at that temperature.

Table 3 listed the temperature at which the pyrolysis degree reaches 0.1 at different heating rates. When the heating rate was

°C/min, the corresponding pyrolysis starting temperature was 910.09 °C, but the actual temperature of the material was 300 °C. Only when the starting temperature of material pyrolysis is less than or equal to the current temperature of the material will pyrolysis occur. So, the material will not be damaged at 300 °C, and when the temperature was equal or greater than 1000 °C, the material will begin to undergo pyrolysis, as shown in

Table 3. Although many studies have recognized that the heating rate affects the pyrolysis of composite materials, the starting temperature of pyrolysis at lower heating rates was still used as the threshold to predict lightning strike damage [

6,

16,

28]. These finding challenges conventional assumptions about heating rate limitations in such materials. The kinetic parameters (A, E, n) used in the pyrolysis-based model were determined through standard thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) experiments at relatively low heating rates. The validity of these parameters is a fundamental assumption of the pyrolysis-based model. However, due to current technical limitations, it is challenging to perform thermogravimetric analysis under extreme heating rates. Consequently, the applicability of these parameters to lightning strike conditions requires further investigation. Previous studies [

6,

17,

20,

24,

28,

36,

41] also use the kinetic parameters determined by standard thermogravimetric analysis experiments to evaluate and analyze lightning ablation damage. Therefore, this issue is the core problem and technical challenge faced in the numerical simulation of lightning damage to composite materials. These findings are based on a theoretical analysis under linear heating rates. In actual lightning strike events, the thermal response of materials involves a more complex heating process.

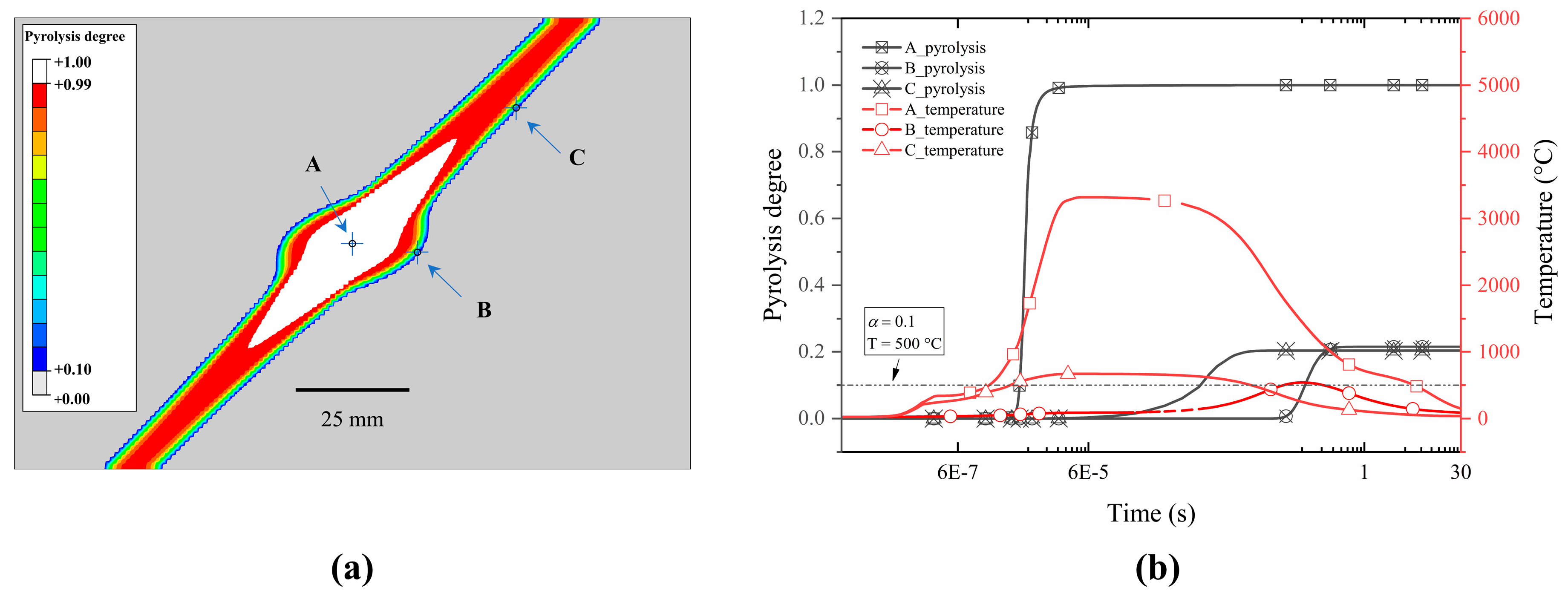

The above analysis results also lead to a crucial topic. Assuming linear heating in step 1, the corresponding temperature when the pyrolysis degree reaches 0.1 is as high as 1000 °C, which inevitably leads to a smaller damage area predicted by the pyrolysis-based model than the temperature-based model, but the opposite is true. This is because the actual temperature-time history of the material is much more complex than the assumed linear case, whether it is the heating in step 1 or the cooling in step 2. To analyze the difference between temperature and pyrolysis degree as damage thresholds, three representative points were selected from the pyrolysis-based model for detailed analysis, as illustrated in the accompanying

Figure 7a. Point A is positioned at the geometric center of the laminate surface, coinciding with the current loading center, which is also the most severely damaged zone. Points B and C are located within the peripheral region of the damage, which is the extension zone of the damage. The temporal evolution of temperature and pyrolysis degree at these three monitoring points was systematically analyzed, with the results presented in the corresponding

Figure 7b. The analysis reveals distinct thermal response characteristics at each monitoring point. The temperature change history of all three points is nonlinear. At point A, located at the current channel’s epicenter, pyrolysis occurs predominantly during step 1, with the pyrolysis degree reaching 0.1 at approximately 1200 °C and an average heating rate of approximately

°C/min. Point B, positioned outside the primary current path, maintains temperatures below 500 °C during stage 1, resulting in minimal pyrolysis (

α < 0.1). During step 2, thermal diffusion mechanism induced a transient temperature increase to 500 °C at point B, followed by subsequent cooling. The highest temperature of point B is 540.3 °C. Notably, material pyrolysis exhibits temperature-dependent behavior, with rapid progression above 500 °C and stagnation below this threshold. The instantaneous heating rate when the pyrolysis degree reaches 0.1 is approximately −7559.65 °C/min. Point C demonstrates intermediate behavior, exceeding 500 °C during stage 1 due to partial current conduction, yet maintaining a pyrolysis degree below 0.1. The highest temperature of point C in step 1 is 669.75 °C, with an average heating rate of

°C/min. The subsequent cooling phase in step 2 triggers a rapid increase in the pyrolysis degree to approximately 0.2 and followed by stagnation as temperatures fall below 500 °C. In the pyrolysis-based model, the relatively low heating rate observed in the damage boundary region results in a material pyrolysis initiation temperature of approximately 500 °C. Points B and C are already positioned at the damage boundary defined by a thermal decomposition degree of 0.1. Consequently, employing 500 °C as the damage threshold appears to provide a valid evaluation criterion for damage assessment within the pyrolysis-based model, which is equivalent to using a pyrolysis degree of 0.1. Since pyrolysis degree is a function of temperature, it can be anticipated that in the temperature-based model, using a pyrolysis degree of 0.1 as the damage threshold would yield identical damage results to those obtained when using 500 °C as the criterion. Therefore, from the perspective of material pyrolysis kinetics, Foster et al. [

25] proposal to use 500 °C to evaluate the lightning damage of composite materials is somewhat reasonable. The equivalence between 500 °C and a pyrolysis degree of 0.1 was established based on a specific resin system; its applicability to other resin systems requires further validation.

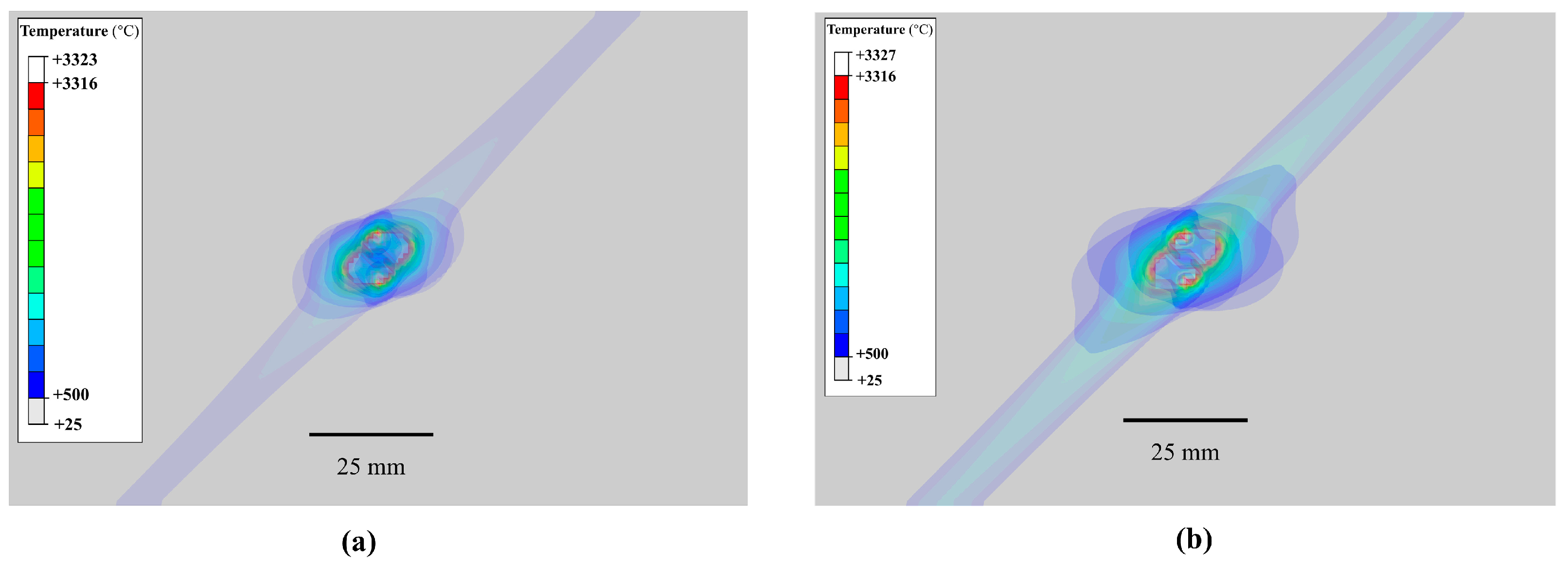

Compared to the temperature-based model using an identical damage threshold of 500 °C, the pyrolysis-based model predicts a significantly larger damage area. This discrepancy suggests that the pyrolysis-based model identifies a more extensive in-plane region exceeding the 500 °C threshold temperature, as shown in

Figure 8. While a temperature threshold of 500 °C effectively quantifies ablation damage in step 2, this criterion fails to remain valid during step 1 under extreme heating rate conditions. As previously established, the pyrolysis initiation temperature at point A surpasses 1000 °C in step 1. Furthermore, both the pyrolysis degree and temperature significantly influence the through-thickness conductivity. The temperature-based model, limited by its inability to account for localized high heating rate phenomena, employs a uniform 500 °C threshold to evaluate bulk conductivity. In contrast, the pyrolysis-based model incorporates localized nonlinear heating behavior, leading to markedly different electrical property predictions. This fundamental divergence in modeling approaches, specifically in their treatment of local thermal effects, explains the observed discrepancies in predicting thermal damage between the two models.

By employing pyrolysis kinetic analysis, the degree of pyrolysis was converted into corresponding temperatures, enabling an effective comparison of the two damage thresholds on the same coordinate axis. This approach robustly reveals the intrinsic differences and similarities between the two models in terms of damage thresholds, while also enhancing the understanding of lightning strike damage mechanisms in composite materials.

4.3. Electrical Conductivity Through-Thickness of Temperature- and Pyrolysis-Based Models

In

Table 1, the electrical conductivity along the fiber direction remains unchanged, while the electrical conductivity perpendicular to the fiber direction changes dramatically with temperature or pyrolysis degree. Based on the given material parameters, the temperature-based model employed in this study assumes a linear change [

16] in electrical conductivity with temperature of 500 °C to 3316 °C, while the pyrolysis-based model assumes a linear change [

17] in electrical conductivity with pyrolysis degree from 0 to 1. To compare the differences in electrical conductivity between the temperature-based model and the pyrolysis-based model during lightning strike, a pyrolysis kinetics analysis based on the linear heating assumption was conducted. The electrical conductivity-temperature curves in the thickness direction of these two models under different heating rates were plotted, as shown in

Figure 9. Pyrolysis-based model exhibits a significant nonlinear relationship between conductivity and temperature. The intersection means that at a given heating rate, the electrical conductivity of these two models in the thickness direction is equal at a certain temperature.

Table 4 presents the temperature and electrical conductivity values at the intersection of the electrical conductivity-temperature curves for these two models in step 1. At heating rates less than

°C/min, indicating material temperatures below 1000 °C in step 1, the intersection temperature exceeded the actual temperature corresponding to the heating rates. Therefore, the electrical conductivity of the pyrolysis-based model between 500 °C and 1000 °C was lower than that of the temperature-based model, while the opposite holds true between 1000 °C and 3000 °C. The transverse electrical conductivity properties were also the same.

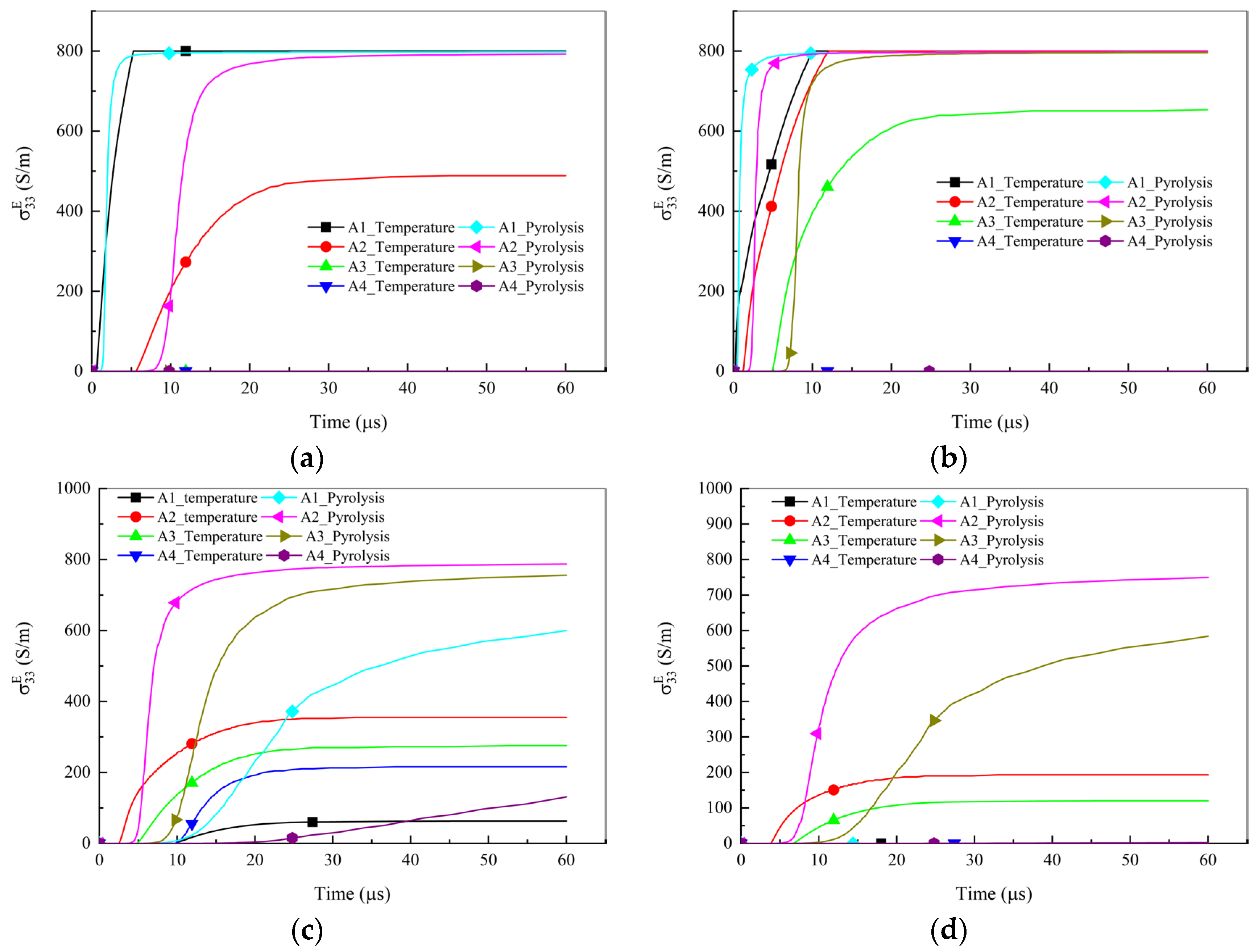

Given that the actual heating rates vary across different locations of the laminate, further analysis of the electrical conductivity at representative positions along the thickness cross section is necessary. A local coordinate system, aligned with the global coordinate system, was established with the laminate center as the origin. At distances of 2 mm, 5 mm, 8 mm, and 10 mm from the laminate center, the top-surface nodes of the first four layers (from the top downward) were selected for comparative analysis, as shown in

Figure 10. Since the electric current is only applied in step 1 (coupled thermal-electrical analysis), the conductivity analysis is confined to this step.

In this study, the electrical conductivity of the material in the thickness direction is dependent on temperature and degree of pyrolysis. Based on this correlation, the real-time temperature and pyrolysis degree of each node can be converted into corresponding conductivity values, thereby enabling the reconstruction of spatially resolved real-time conductivity profiles throughout the material, as shown in

Figure 11. Consistent with the linear heating analysis results, at the same location, the temperature-based model initially exhibits a higher electrical conductivity than the pyrolysis-based model. However, the conductivity predicted by the pyrolysis-based model then increases rapidly and eventually surpasses that of the temperature-based model. The conductivity stabilizes at 30 μs, as the lightning impulse current decays rapidly and the material temperature shows no significant variation beyond this time point.

When the distance from the laminate center is 2 mm or 5 mm, the conductivity at position A1 in both models increases rapidly and reaches its maximum value first among the four positions, as shown in

Figure 11a,b. However, at distances of 8 mm and 10 mm from the laminate center, the conductivity at A1 increases more slowly or even remains largely unchanged, while position A2 shows a rapid conductivity increase, as shown in

Figure 11c,d. This phenomenon occurs because the current application radius is 5 mm, and the current primarily flows along the in-plane fiber direction. When the distance exceeds 5 mm and deviates from the fiber direction, where the current center is located, the current’s effect on A1 diminishes significantly. In contrast, point A2, located in the fiber direction of the second layer, remains consistently influenced by the current.

At positions A1 (D = 2 mm and D = 5 mm), a uniform in-plane current is applied as an initial condition. As material temperature increases, the temperature-based model exhibits earlier enhancement of through-thickness conductivity, causing a significant reduction in overall resistance. This facilitates current penetration and expansion of the conduction network. In contrast, the pyrolysis-based model demonstrates delayed through-thickness conductivity development due to heating rate effects, maintaining predominant surface current flow. This concentrated current generates intensified Joule heating, leading to a rapid temperature rise. This rise subsequently accelerates the through-thickness growth of electrical conductivity, causing it to exceed the predictions of the temperature-based model. Therefore, when current begins to conduct through the laminate thickness, the pyrolysis-based model demonstrates significantly delayed conductivity compared to the temperature-based model. With an initial through-thickness conductivity of only 0.0018 S/m, the maximum conductivity difference between these two models reaches two orders of magnitude (100 times) in the thickness direction. Although the pyrolysis-based model’s conductivity eventually surpasses the temperature-based model in later stages, the maximum excess remains below 10-fold. These mechanisms result in substantially lower effective through-thickness conductivity in the pyrolysis-based model’s first layer, promoting preferential shallow current flow that generates larger damage areas. When A1 approaches ablation completion, current gradually transfers to underlying layers, inducing temperature rise at A2. Nodes A2 and A3 exhibit analogous through-thickness conductivity evolution patterns to A1. This process repeats at A2/A3 positions (D = 8 mm and 10 mm). Consequently, the heating rate-induced conductivity delay in the pyrolysis-based model fundamentally explains its prediction of larger damage areas but shallower depths.

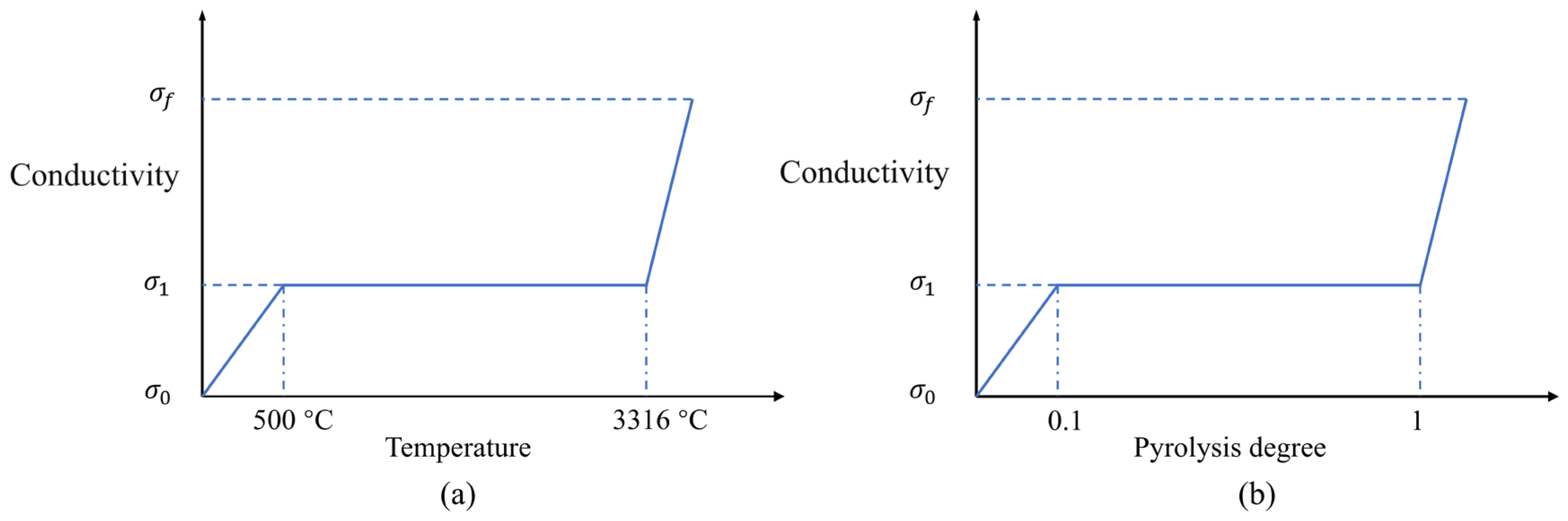

Notably, this study is confined to the linear conductivity assumption. While this simplification facilitates a focused comparison, it prompts discussion on the implications for nonlinear conductivity models. Existing nonlinear conductivity models [

28] typically postulate that through-thickness conductivity remains constant once the temperature or pyrolysis degree exceeds the damage threshold, and conductivity increases abruptly upon material ablation, as shown in

Figure 12. A key insight from our previous analysis is that the pre-threshold conductivity evolution is a critical phase differentiating the two models, where the pyrolysis-based model lags significantly due to local heating rate effects. We hypothesize that if this pre-threshold lag mechanism persists in a nonlinear modeling framework, it could potentially lead to even more pronounced discrepancies in damage prediction. However, validating this hypothesis requires dedicated simulations with nonlinear conductivity laws, which is beyond the scope of this study. Therefore, the findings presented here are specific to the linear conductivity model, yet they highlight a pre-damage conductivity lag mechanism that should be considered in the development or interpretation of any conductivity model, linear or nonlinear, for lightning strike simulation.

Using pyrolysis kinetic analysis, the degree of pyrolysis was converted into corresponding temperatures, allowing for an effective comparison of the through-thickness conductivity values of the two models on the same coordinate axis. This approach clearly demonstrates the differences in through-thickness conductivity between the two models and, based on these conductivity variations, further analyzes the origins of their discrepancies in damage prediction. These findings advance the understanding of lightning strike damage mechanisms in composite materials.

4.4. Joule Energy of Temperature- and Pyrolysis-Based Models

The Joule heat generated during lightning current conduction directly governs the thermal loading that drives damage. Therefore, comparing the Joule energy provides a macroscopic indicator of the models’ overall electrical-thermal response, complementing the conductivity analysis in

Section 4.3.

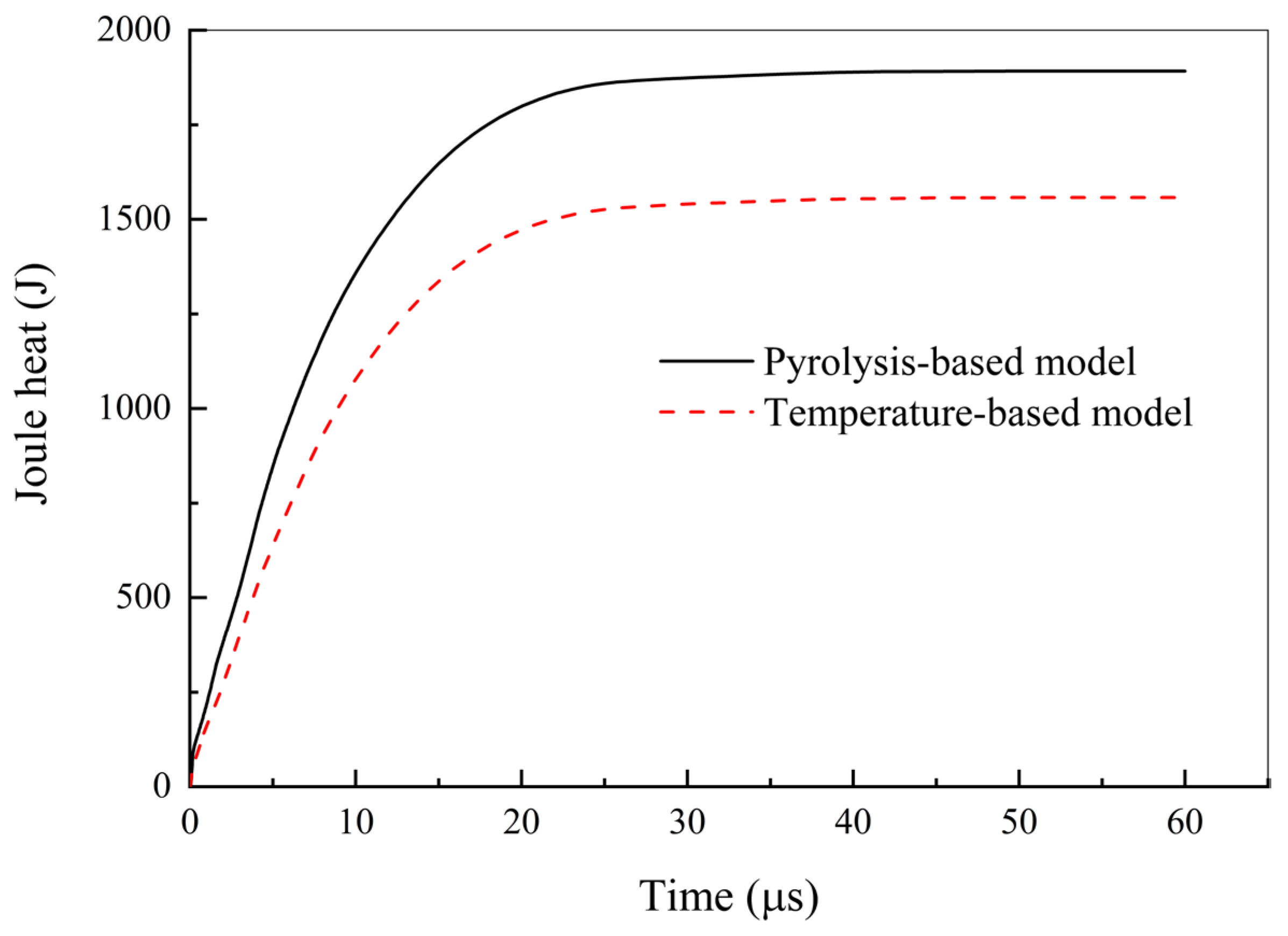

As shown in

Figure 13, the pyrolysis-based model generated about 1892.13 J of total Joule heat, which is about 334.59 J more than the temperature-based model (1557.54 J). This finding is a direct consequence of the delayed through-thickness conductivity development identified earlier. During the critical initial phase of current conduction, the pyrolysis-based model exhibits significantly lower through-thickness conductivity (

Figure 11), resulting in a higher overall resistance. For a prescribed current waveform, this increased resistance naturally leads to greater cumulative Joule heating, as quantified here.

The practical implication of this higher Joule heat is consistent with the predicted damage morphology. The additional energy generated in the pyrolysis-based model contributes to a more extensive in-plane temperature field (as seen in

Figure 8), which directly translates to the larger predicted damage area discussed in

Section 4.1. Thus, Joule heating analysis does not stand alone; it provides strong validation for the relationship between the conductivity hysteresis dependent on local heating rate (

Section 4.3) and the final damage (

Section 4.1).

It is worth noting that due to the scarcity of such data in the references, it is not possible to directly quantitatively verify the simulated energy values based on experimental measurements. The future work of synchronously measuring current, voltage, and temperature during lightning strike testing will be very valuable for fully calibrating and verifying the energy balance predicted by these coupled models.