Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen/Hydrogen Peroxide Propellant Combination for Advanced Launch Vehicle Upper Stage

Abstract

1. Introduction

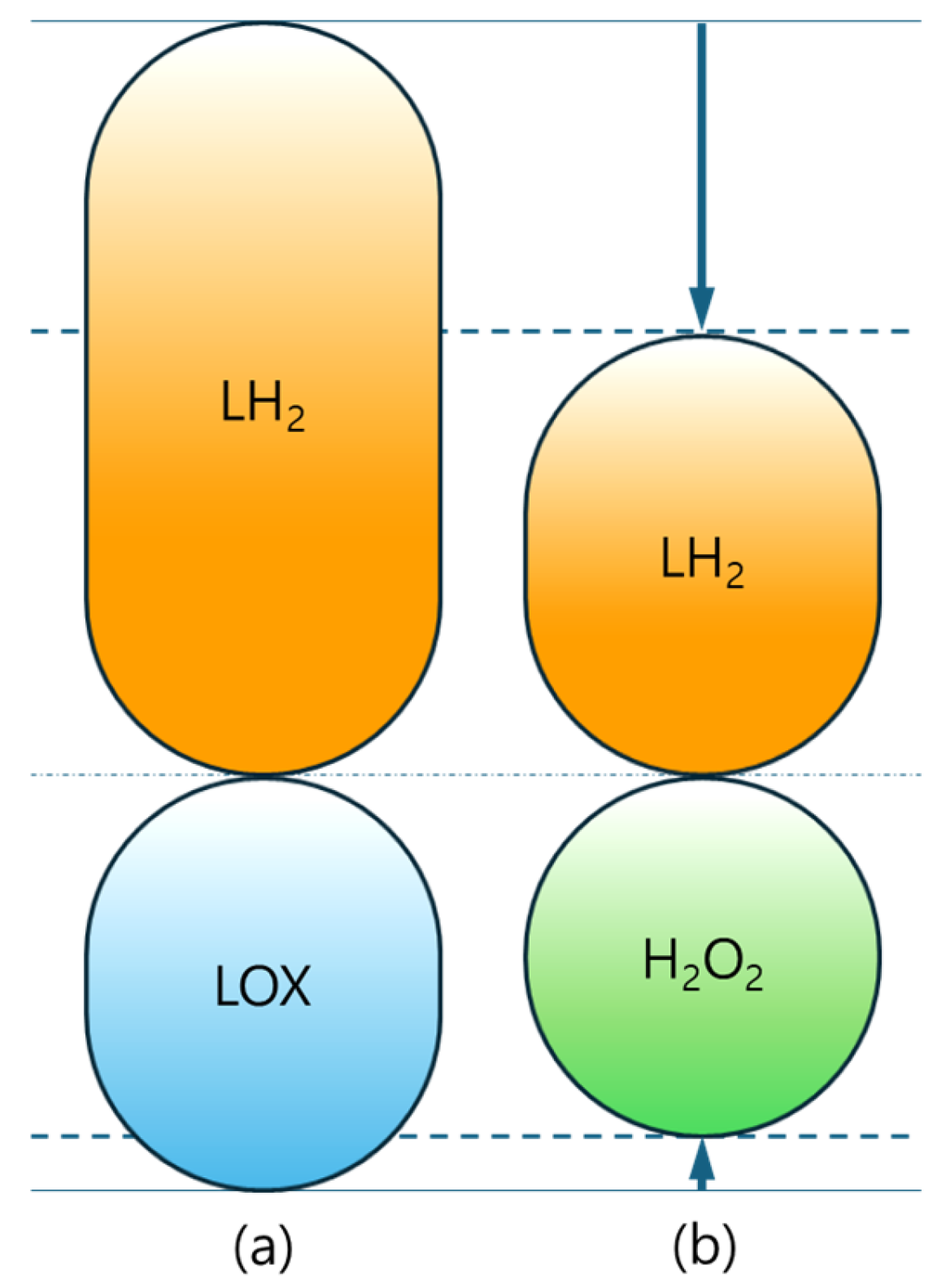

2. Applicability of Liquid Hydrogen/Hydrogen Peroxide Combination

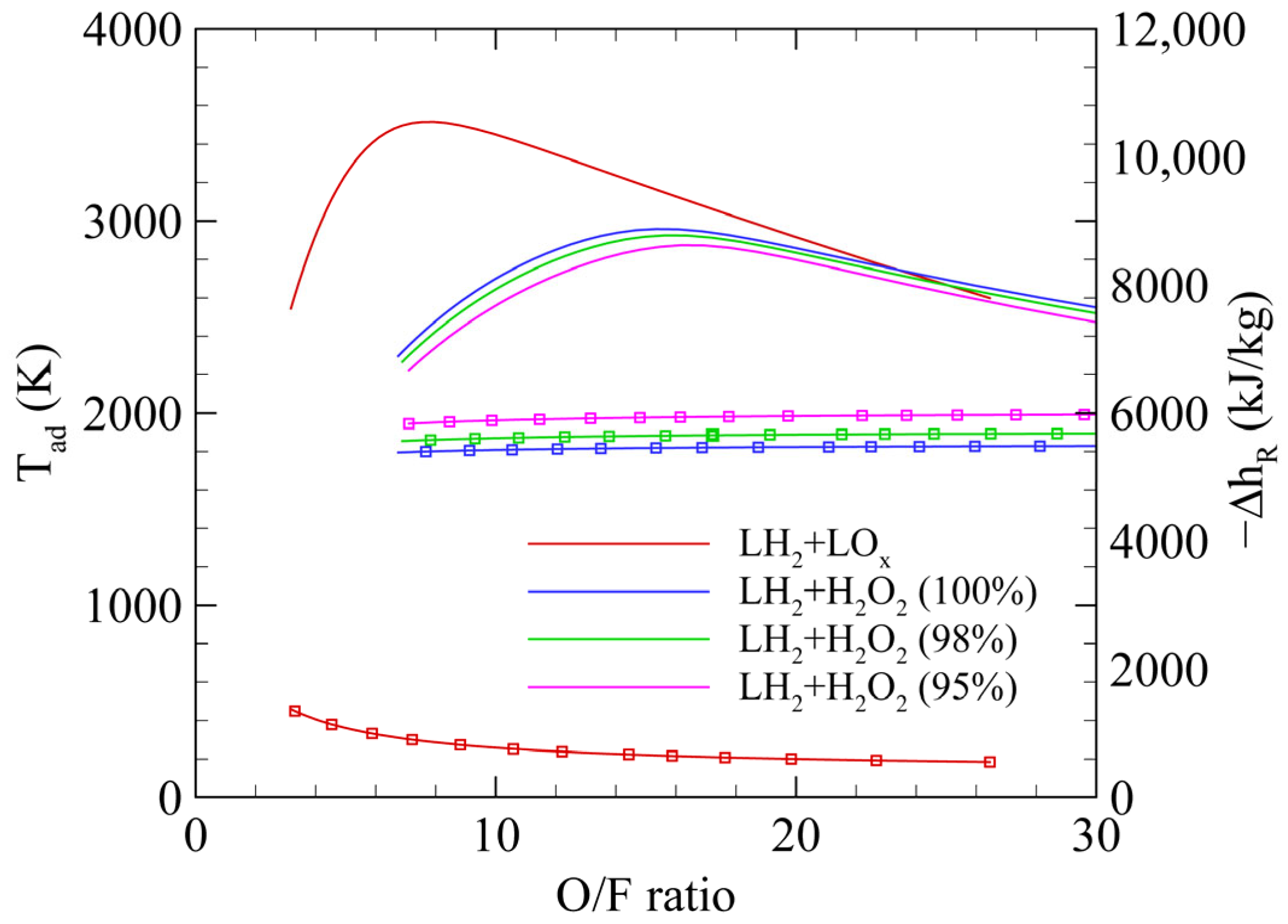

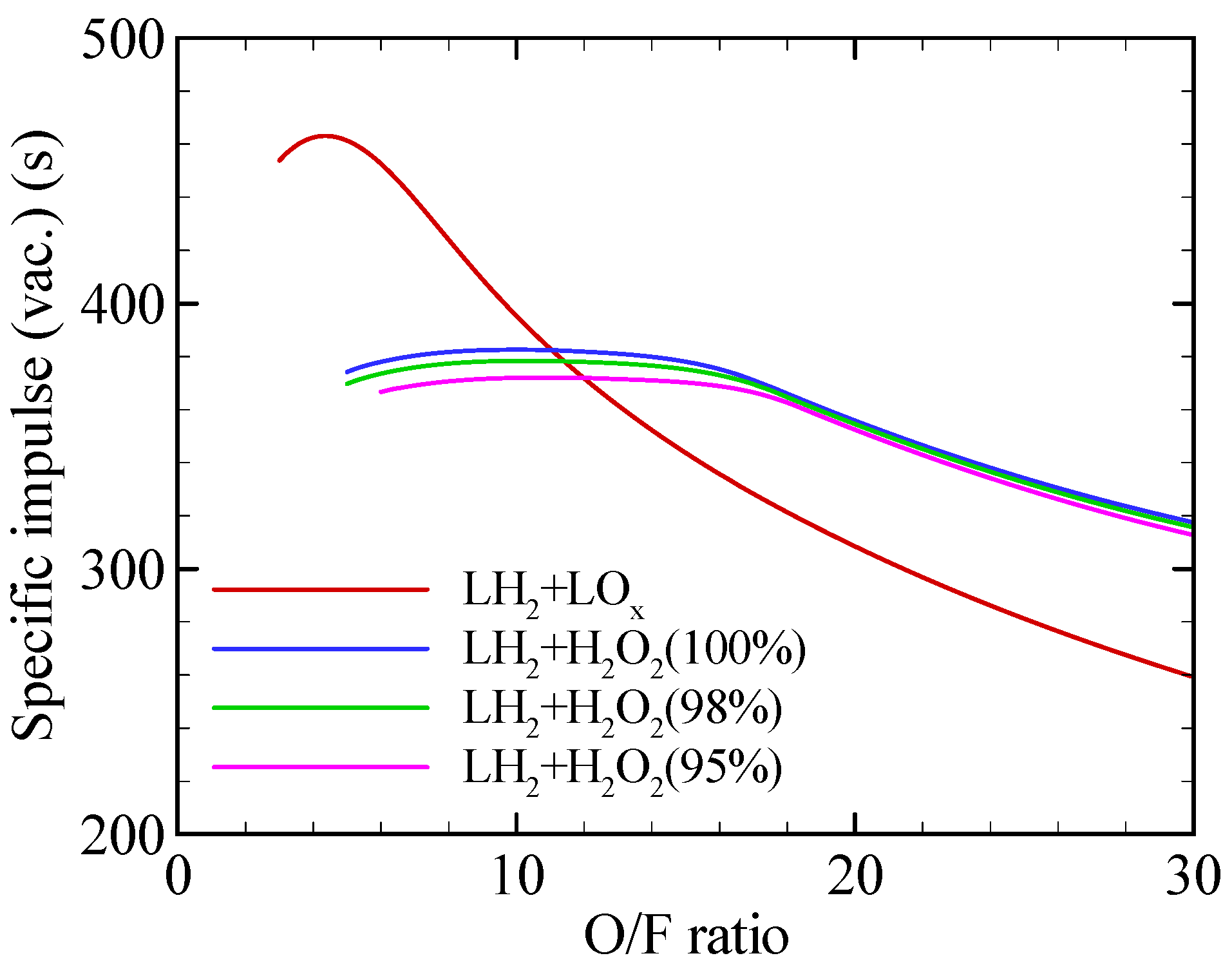

2.1. Propulsion Performance

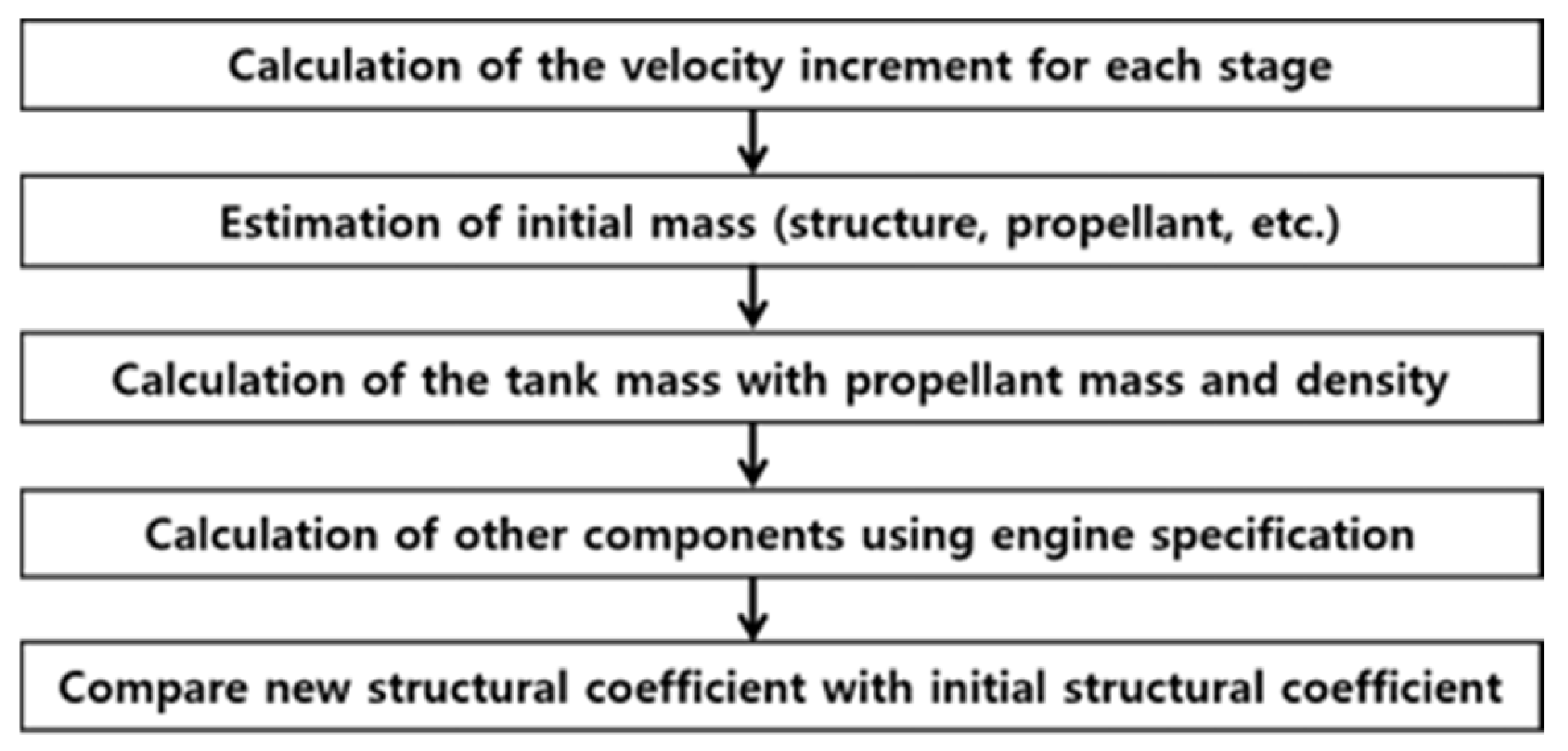

2.2. Methodology of Launch-Vehicle Performance Calculation

3. System-Level Impact of Oxidizer Change for the Upper Stage

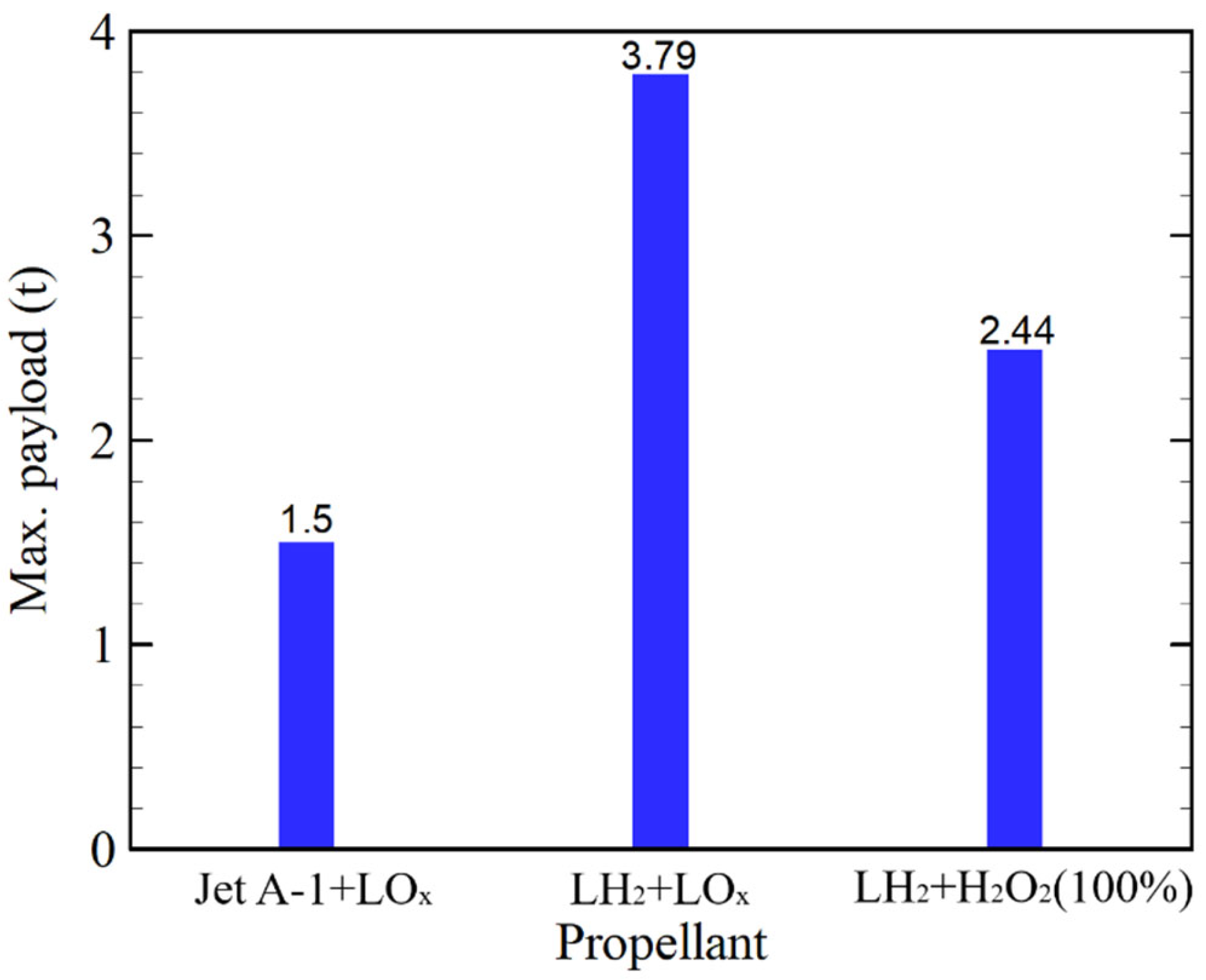

3.1. System-Level Results of Liquid Hydrogen/Hydrogen Peroxide Upper Stage

3.2. Implications and Context with Previous Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, W.-S.; Kim, S.-Y.; Choi, J.-Y. Conceptual Design of a Launch Vehicle for Lunar Exploration by Combining Naro-1 and KSLV-II. J. Korean Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2014, 42, 654–660. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.; Jo, M.-S.; Kang, S.-Y.; Choi, J.-Y. Optimizing Systems Engineering Procedure for the Development of a Sounding Rocket. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.-S.; Kim, J.-E.; Choi, J.-Y. Staging and Injection Performance Analysis of Small Launch Vehicle Based on KSLV-II. J. Korean Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2021, 49, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.-S.; Cho, D.-H.; Choi, J.-Y. Performance Analysis of Small Launch Vehicles Using Algebraic Model: Case Studies Based on KSLV-II 2nd and 3rd Stage. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2025, 26, 2885–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Yang, S.-M.; Choi, J.-Y. Analysis of Orbit Injection Performance of KSLV-II by Weight Reduction. J. Korean Soc. Prop. Eng. 2018, 22, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, M.; Yang, S.-M.; Kim, H.-S.; Yoon, Y.; Choi, J.-Y. Comparison of the Mission Performance of Korean GEO Launch Vehicles for Several Propulsion Options. J. Korean Soc. Prop. Eng. 2017, 21, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-S.; Oh, S.; Choi, J.-Y. Quasi-1D analysis and performance estimation of a sub-scale RBCC engine with chemical equilibrium. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.-S.; Kim, J.-E.; Choi, J.-Y. Comparison of Upper-Stage Engine Options for Small Launch Vehicle Based on KSLV-II. In Proceedings of the AIAA Propulsion and Energy Forum, Virtual Event, 9–11 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, M.; Mullens, P. The Use of Hydrogen Peroxide for Propulsion and Power. In Proceedings of the 35th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 20–24 June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Skyrora. The History of the UK Black Arrow Rocket Programme; Skyrora: Glasgow, UK, 2024; Available online: https://skyrora.com/the-history-of-the-uk-black-arrow-rocket-programme/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Pasini, A.; Torre, L.; Romeo, L.; Cervone, A.; d’Agostino, L. Testing and Characterization of a Hydrogen Peroxide Monopropellant Thruster. J. Propuls. Power 2008, 24, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Wernimont, E.; Heister, S.; Yuan, S. Rocket Grade Hydrogen Peroxide (RGHP) for Use in Propulsion and Power Devices—Historical Discussion of Hazards. In Proceedings of the 43rd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 8–11 July 2007; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2007. AIAA 2007-5468. [Google Scholar]

- Musker, A.J. Highly Stabilised Hydrogen Peroxide as a Rocket Propellant. In Proceedings of the 39th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Huntsville, AL, USA, 20–23 July 2003; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2003. AIAA 2003-4619. [Google Scholar]

- Florczuk, W.; Rarata, G.P. Performance Evaluation of the Hypergolic Green Propellants Based on the HTP for a Future Next Generation Spacecrafts. In Proceedings of the 53rd AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–12 July 2017. AIAA 2017-4849. [Google Scholar]

- Okninski, A.; Surmacz, P.; Bartkowiak, B.; Mayer, T.; Sobczak, K.; Pakosz, M.; Kaniewski, D.; Matyszewski, J.; Rarata, G.; Wolanski, P. Development of Green Storable Hybrid Rocket Propulsion Technology Using 98% Hydrogen Peroxide as Oxidizer. Aerospace 2021, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Jang, D.; Kwon, S. Demonstration of 500 N Scale Bipropellant Thruster Using Non-Toxic Hypergolic Fuel and Hydrogen Peroxide. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2016, 49, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okninski, A.; Surmacz, P.; Sobczak, K.; Florczuk, W.; Cieslinski, D.; Gorgeri, A.; Bartkowiak, B.; Kublik, D.; Ranachowski, M.; Gut, Z.; et al. Development of Green Bipropellant Thrusters and Engines Using 98% Hydrogen Peroxide as Oxidizer. Aerospace 2025, 12, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, G.P.; Biblarz, O. Rocket Propulsion Elements, 9th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, G.K.; Starrett, W.D.; Jensen, K.C. Development and Lab-Scale Testing of a Gas Generator Hybrid Fuel in Support of the Hydrogen Peroxide Hybrid Upper Stage Program. In Proceedings of the 37th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 8–11 July 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rarata, G.; Rokicka, K.; Surmacz, P. Hydrogen Peroxide as a High Energy Compound Optimal for Propulsive Applications. Cent. Eur. J. Energ. Mater. 2016, 13, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, W.R.; Cho, S.B.; Sun, B.C.; Choi, K.S.; Jung, D.W.; Park, C.S.; Oh, J.S.; Park, T.H. Mission and System Design Status of Korea Space Launch Vehicle-II Succeeding Naro Launch Vehicle. In Proceedings of the Korean Society for Aeronautical and Space Sciences Fall Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 22–23 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, R.; Génin, C.; Schneider, D.; Fromm, C. Ariane 5 Performance Optimization Using Dual-Bell Nozzle Extension. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2016, 53, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; McBride, B.J. Computer Program for Calculation of Complex Chemical Equilibrium Compositions and Applications; NASA Reference Publication 1311; NASA: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1996.

- Ponomarenko, A. RPA—Tool for Rocket Propulsion Analysis. In Proceedings of the Space Propulsion Conference, Cologne, Germany, 19–22 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, M. Long Term Storability of Hydrogen Peroxide. In Proceedings of the 41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Tucson, AZ, USA, 10–13 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Akin, D.L. Mass Estimating Relations; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.H.; Cho, S.Y. Space Launch Vehicle Development in Korea Aerospace Research Institute. In Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2016 Conference, Dajeon, Republic of Korea, 16–20 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kopacz, W.; Okninski, A.; Kasztankiewicz, A.; Nowakowski, P.; Rarata, G.; Maksimowski, P. Hydrogen Peroxide—A Promising Oxidizer for Rocket Propulsion and Its Application in Solid Rocket Propellants. FirePhysChem 2022, 2, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzybut, A.; Surmacz, P.; Gut, Z. Impact of Hydrogen Peroxide Concentration on Manganese Oxide and Platinum Catalyst Bed Performance. Aerospace 2023, 10, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, D.A.; Natan, B. Hypergolic Ignition of Hydrogen Peroxide with Various Solid Fuels. Fuel 2022, 316, 123432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.-S.; Li, M.-C.; Lai, A.; Chou, T.-H.; Wu, J.-S. A Review of Recent Developments in Hybrid Rocket Propulsion and Its Applications. Aerospace 2024, 11, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Thrust (N) | 64,800 |

| Chamber pressure (bar) | 40 |

| Nozzle expansion ratio | 83.1 |

| Cycle | Gas-generator |

| Oxidizer | LOX | H2O2 (100%) | H2O2 (98%) | H2O2 (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equivalence ratio | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.55 |

| O/F ratio | 5.12 | 10.55 | 10.76 | 11.46 |

| Specific impulse (s) | 465.6 | 382.3 | 378.3 | 372.1 |

| Adiabatic temperature (K) | 3270 | 2747 | 2710 | 2679 |

| Enthalpy of reaction (kJ/kg) | −1069.8 | −5429.6 | −5616.6 | −5.902.1 |

| Oxidizer | LOX | H2O2 (100%) | H2O2 (98%) | H2O2 (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage mass (t) | 5.79 | 8.29 | 8.5 | 8.8 |

| Specific impulse (s) | 465.6 | 382.3 | 378.3 | 372.1 |

| O/F ratio | 5.12 | 10.55 | 10.76 | 11.46 |

| Fuel mass (t) | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| Oxidizer mass (t) | 2.94 | 5.43 | 5.62 | 5.95 |

| Tank height (m) | 2.01 | 2.07 | 2.13 | 2.17 |

| Structural coefficient | 0.162 | 0.102 | 0.101 | 0.099 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jo, M.-S.; Choi, J.-Y. Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen/Hydrogen Peroxide Propellant Combination for Advanced Launch Vehicle Upper Stage. Aerospace 2026, 13, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010023

Jo M-S, Choi J-Y. Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen/Hydrogen Peroxide Propellant Combination for Advanced Launch Vehicle Upper Stage. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleJo, Min-Seon, and Jeong-Yeol Choi. 2026. "Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen/Hydrogen Peroxide Propellant Combination for Advanced Launch Vehicle Upper Stage" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010023

APA StyleJo, M.-S., & Choi, J.-Y. (2026). Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen/Hydrogen Peroxide Propellant Combination for Advanced Launch Vehicle Upper Stage. Aerospace, 13(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010023