1. Introduction

Shockwave/boundary layer interaction is a widely prevalent phenomenon in the external and internal flows of all types of hypersonic or supersonic aircraft. It is a typical flow phenomenon common in the high-speed flight of aircraft. It is also one of the key problems in the design and development of hypersonic aircraft and engines [

1].

The shockwave and boundary layer interaction flow phenomena in the flow field of hypersonic/hypersonic aircraft primarily include compression corner [

2], plate-incident shockwave interaction [

3], internal channel three-dimensional interaction [

4], swept-back compression corner [

5], column–skirt interaction [

6], and others. Among them, flat-incident shockwave interaction and internal channel three-dimensional interaction primarily occur within the internal flow of an aircraft. In contrast, back-swept compression corner and pillar–skirt interaction primarily occurs in the external flow of an aircraft [

6]. Shockwave/boundary layer interaction induced by a compression corner is common in both the internal and external flow of aircraft. The compression corner SWBLI phenomenon occurs when the compression surface profile in the inlet is deflected [

7]. In the outflow, the compression corner SWBLI phenomenon often occurs at the body joint of the aerodynamic profile [

8]. In practical engineering applications, continuous compression is usually applied at the joints of the external body or in the external fin/rudder structure. In internal flow, multistage compression schemes are often employed at the inlet to enhance total pressure recovery. Therefore, the compression corner SWBLI in the actual scene is usually a multistage compression corner shockwave/boundary layer interaction problem. The multi-channel shock structure in the multistage compression corner shockwave/boundary layer interaction flow field makes the flow field structure more complex [

9]. It is usually simplified to Double Compression Ramp Shockwave/Boundary Layer Interaction (DCR-SWBLI) in research [

10].

However, at present, in the research field of corner-induced shockwave/boundary layer interaction characteristics under supersonic/hypersonic compression, most of the research focuses on the interaction characteristics under supersonic conventional noise, and relatively few studies have been conducted on the interaction characteristics under multistage/double compression corner shockwave/boundary layer interaction and hypersonic conditions. There are fewer studies on low-noise conditions or quiet downflows [

11,

12]. It should be emphasized that, in the actual working environment of hypersonic vehicles, the difference between the current surface wind tunnel inflow disturbance/noise level and the upper atmosphere inflow disturbance/noise level is a key factor affecting vehicle design.

Compared with the experimental results of the conventional wind tunnel and the quiet wind tunnel in ref. [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], the conventional hypersonic wind tunnel has significant free flow noise. It cannot replicate the turbulent structure of the real, quiet high-altitude flight environment, which directly affects research on hypersonic boundary layer transition and the shockwave/boundary layer interaction mechanism. In contrast, the free flow turbulence of the quiet wind tunnel is comparable to that of the real flight environment. The experimental results for predicting boundary layer transition or disturbance regions are in closer agreement with the theoretical analysis results. Therefore, aiming at the difference in orders of magnitude in turbulence between the experimental flow field of a hypersonic vehicle in the ground wind tunnel and the real flight environment [

18], based on the quiet wind tunnel, if the multistage compression corner disturbance characteristics can be studied in both quiet mode (incoming turbulence less than 0.1%), low noise mode (incoming turbulence 0.1~0.5%), and conventional noise mode (incoming turbulence greater than 2.0%) [

19], it will provide more powerful support for the design of the external profile of the aircraft or the advanced air intake system [

20,

21].

Based on the hypersonic quiet wind tunnel, this paper presents an experimental study on the characteristics of hypersonic shockwave/boundary layer interaction under quiet and noisy incoming flow conditions for the double compression corner-plate model. It explored the typical shockwave/boundary layer interaction and the typical structure of shockwave/shockwave interaction above the corner under conditions of quiet and noisy incoming flow using the high-speed Schlieren method. Based on the gray average, RMS analysis, spatial FFT, the POD method, and the DMD method, the time-average and unsteady characteristics of double compression corner configuration-induced separation were studied, and the relationship between wind tunnel noise level and interaction characteristics was summarized. Finally, the characteristic length and spectral characteristics of unstable waves that dominated the stability of the flat boundary layer were discussed. The formation mechanism of separation is discussed, which provides technical support for the internal and external aerodynamic design and targeted optimization of hypersonic vehicles.

2. Experimental Arrangement and Method

The Φ300 mm hypersonic low noise wind tunnel of China Aerodynamics Research and Development Center is the first hypersonic low noise wind tunnel with Ludwig tube operation mode in China [

22]. The whole experiment system mainly included a low noise wind tunnel, flat-plate compression corner model, high-speed Schlieren system, synchronous control system, etc.

2.1. Hypersonic Low Noise Wind Tunnel and the High-Speed Schlieren System

The experiments were carried out in the Φ300mm hypersonic quiet wind tunnel of the Ultra-High Speed Aerodynamics Institute of the China Aerodynamics Research and Development Center. The actual picture of the wind tunnel is shown in

Figure 1.

The experimental condition is set at Mach 6 and the total temperature is 457 K. According to the operation characteristics of the wind tunnel, after the establishment of the flow field, the flow field in the test section first experiences a noise flow state (unit Reynolds number is 9.4 × 10

6) for a period of time, and then enters a quiet flow field state (unit Reynolds number is 5.7 × 10

6). The characteristics of shockwave/boundary layer interaction induced by double compression corner are studied under different noise levels under fixed incoming flow conditions. The test conditions are shown in

Table 1.

It is tough to conduct contact measurements in the highly advanced environment of Mach 6. In addition, the research must also consider the influence of plasma and pay closer attention to the changes in the structure of the wave system. Therefore, we have chosen the most stable and mature non-contact measurement method for flow field measurement. High-speed Schlieren imaging is performed using a masterconjugate mirror system. Unlike the conventional Schlieren system, the slit and knife-edge use the same horizontal structure of off-axis polished objects, as shown in

Figure 2. In this structure, spherical mirrors used in the traditional Z-Schlieren system can eliminate spherical aberrations and non-point aberrations [

23]. In the experiment, a Phantom V2512 model camera was used, along with a Nikon lens with a focal length of 200 mm and an f-value of 1/4. The knife-edge cut ratio was set to 0.5. The maximum resolution of the camera used in the experiment was 2048 pixels × 2048 pixels. The target size was 20.48 mm × 20.48 mm, the pixel size was 10 μm, the frame frequency of the Schlieren was set to 50 kHz, and the exposure time was 2.7 μs.

2.2. Double Compression Corner-Flat Model and Synchronous Control System Settings

The experimental model adopts the combination model of the double compression corner and plate. The plate length is 427.7 mm, the width is 160 mm, and the leading edge wedge angle is 10°. The leading edge of the double compression corner is located at a flow direction of the plate, x = 257 mm, and the angles of the two folds are 30° and 45°, respectively. The total flow direction length is 55 mm. The flow direction length of the first bend angle is about 40 mm, and the height of the model is about 38 mm.

Figure 3 illustrates the design of the combined model, featuring a double compression corner and a flat plate. Considering the possible existence of three-dimensional effects in hypersonic flow fields, this study focuses on two-dimensional shockwave/boundary layer interaction problems. Therefore, the corner width was not set to be the same as the plate width, but was made smaller than the plate width (40 mm) to minimize the interaction of three-dimensional effects on this experiment to the greatest extent. The blockage ratio of this model in the wind tunnel is 5.4%, which meets the normal start-up conditions of the wind tunnel.

The synchronization control settings are shown in

Figure 4. In the characteristic research experiment, it is essential to determine the accurate delay time according to the flow state of the quiet wind tunnel. According to different delay trigger times, the interaction flow field data under quiet flow and noise flow conditions are recorded by a high-speed CCD camera. Among them, the delay time of the delay signal is 50 μs.

2.3. Overview of Research Method

After the test condition is determined, the time sequence snapshot of quiet flow and conventional noise flow is recorded by the high-speed Schlieren system. Through gray average analysis, root-mean-square analysis, fast Fourier transform spectrum analysis, proper orthogonal decomposition (POD), dynamic mode decomposition analysis (DMD) and spatial Fourier transform, the results of average flow field, flow field pulsation, flow field characteristic spectral characteristics, flow field unsteady characteristic structure, unsteady dynamic mode of flow field and boundary layer unstable wave development are, respectively, analyzed analysis of interaction characteristics.

3. Research on Hypersonic Shockwave/Boundary Layer Interaction Characteristics

3.1. Time-Average Characteristic Analysis

First, the basic structure results of the interaction flow field are focused on.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the instantaneous Schlieren comparison results and the average Schlieren gray comparison results under the conditions of noisy incoming flow and quiet incoming flow, respectively.

The schlieren results reveal the formation of a classic double compression corner shockwave/boundary layer interaction flow field structure in the hypersonic flow, along with a shock–shock interaction structure directly above the compression corner. A background shockwave is observed obliquely upstream of the flat plate, generated by the tip effect at the model’s leading edge, whose influence on the study and flow field can be neglected. From the flat-plate leading edge to the compression corner leading edge, the laminar boundary layer exhibits a linear growth trend, progressively thickening along the freestream direction. During the development of the boundary layer, a distinct “lift-up” trend is observed at a specific location, accompanied by the emergence of a faint separation shock. This point is identified as the onset of flow separation, and the region between this point and the intersection of the boundary layer with the model leading edge is defined as the separation zone. Due to the “obstruction” caused by the compression corner model, the gas is compressed, leading to the formation of a strong reattachment shock nearby, which reflects intensely after the shockwave. At the leading edge of the second compression corner, the gas is compressed again, generating a second intense shockwave. The interaction between this shock and the first reattachment shock results in the formation of an even stronger shockwave and a relatively weaker reflected shock, with a slip line emerging between the two. Based on the interpretation of the noisy flow field results, the separation zone length is measured to be 62.5 mm.

In contrast, although the quiet flow field exhibits a generally consistent structure with the noisy flow field, the distribution and spatial positioning of the flow structures show notable differences. This is primarily reflected in the earlier onset of flow separation and a significantly larger separation zone compared to the noise flow field. The separation zone length in this case is 90 mm, representing a 44% increase relative to the noisy flow field.

We further analyze the reasons for the differences in the separation zone of the two. Under identical model configurations and Mach numbers, the larger separation zone observed in a quiet tunnel is fundamentally governed by the decisive influence of freestream disturbance levels on boundary layer stability. The exceptionally low freestream turbulence in a quiet field enables the boundary layer to maintain a laminar state over a greater streamwise extent. This laminar boundary layer, characterized by a “skinny” velocity profile and insufficient near-wall momentum, exhibits high sensitivity to the adverse pressure gradient induced by the shockwave, leading to premature and facile separation. In contrast, the high-disturbance environment of a conventional noise field promotes an early transition to a turbulent boundary layer. The robust momentum mixing inherent to turbulence continuously transports high-momentum fluid toward the near-wall region, thereby enhancing its resistance to the adverse pressure gradient and suppressing separation. Even when separation occurs, the subsequent reattachment process is facilitated by more intense mixing, resulting in a smaller overall separation bubble compared to the quiet field scenario.

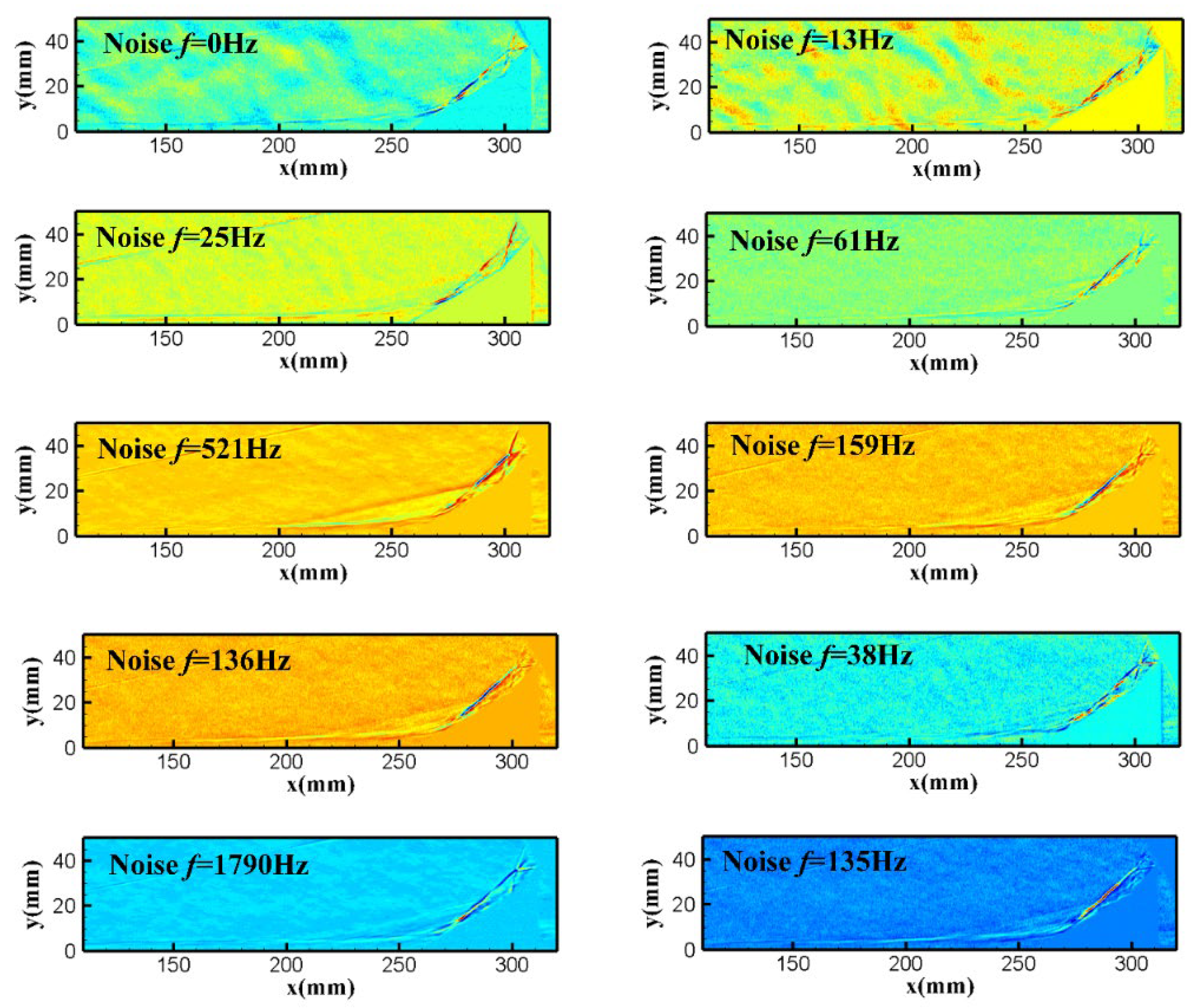

Figure 7 shows the RMS comparison results of the disturbed flow field. It can be seen that the pulsation level of the boundary layer is higher when the noise is flowing down, and the pulsation levels of the secondary shockwave, intense shockwave, and slip line are also higher, indicating that the unsteady characteristics of the disturbed flow field are more pronounced under noise incoming.

3.2. Analysis of Unsteady Characteristics

To study the unsteady characteristics of the interaction flow field, a gray matrix is selected for the Fourier transform based on the time-series Schlieren image, allowing for the monitoring of the unsteady characteristics of different interaction structures. The selected gray monitoring area is a straight line, approximately 62 pixels in length, and the selected time period is 500 ms. Fourier transform is performed on the gray time-series changes in the time period, and the characteristic frequency of the unsteady oscillation of the corresponding interaction structure is obtained.

The selection area of the grayscale matrix is shown in

Figure 8. Grayscale matrix ① corresponds to the root of the attached shockwave, grayscale matrix ② corresponds to the middle of the attached shockwave, grayscale matrix ③ corresponds to the slip line region, and grayscale matrix ④ corresponds to the strong shock region.

During the PSD analysis process, Hanning and Blackman windows with 50% overlap were used, detrending was applied via a third-order Butterworth low-pass filter at 20 kHz, and Welch’s method with multiple block averaging was employed.

Figure 9 reflects the PSD curve obtained from the unsteady analysis of the Fourier transform. It can be observed that under the condition of noise flow, the main frequency components of the root of the secondary shockwave, the middle of the secondary shockwave, and the strong shockwave region are apparent, and the frequency peaks of the slip line region are more prominent. For quiet downflow, no obvious main frequency information can be extracted from the middle and strong shock region of the secondary shockwave. However, clear frequency information can be extracted from the root and slip line region of the secondary shockwave.

From the comparative analysis of each region, the unsteady motion in the slip line region is the most intense. The unsteady motion characteristics of the secondary shockwave and the intense shockwave are not apparent in the middle of the secondary shockwave and the strong shockwave region, which is consistent with the results of RMS.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, an experimental study of hypersonic shock/boundary layer interaction characteristics is conducted under quiet and noisy incoming flow, conditions, respectively, for the double compression corner-plate model. Using high-speed Schlieren imaging, the typical structures of shock/boundary layer interaction and shock/shock interaction above the corner are explored under both quiet and noisy incoming flow conditions. Then, based on the gray average, RMS analysis, spatial FFT, POD, and DMD methods, the time-average and unsteady characteristics of the double compression corner configuration-induced separation were studied, and the difference law of the wind tunnel noise level on interaction characteristics was summarized. Finally, from the perspective of the development of unstable waves leading to the stability of the flat-plate boundary layer, the formation mechanism of separation is discussed. This provides technical support for the aerodynamic design inside and outside the hypersonic vehicle and the research and optimization of targeted effects (drag, total pressure loss, heating load downstream, etc.).