Nitrous Oxide-Hydrocarbon Liquid Propellants for Space Propulsion: Premixed and Non-Premixed Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

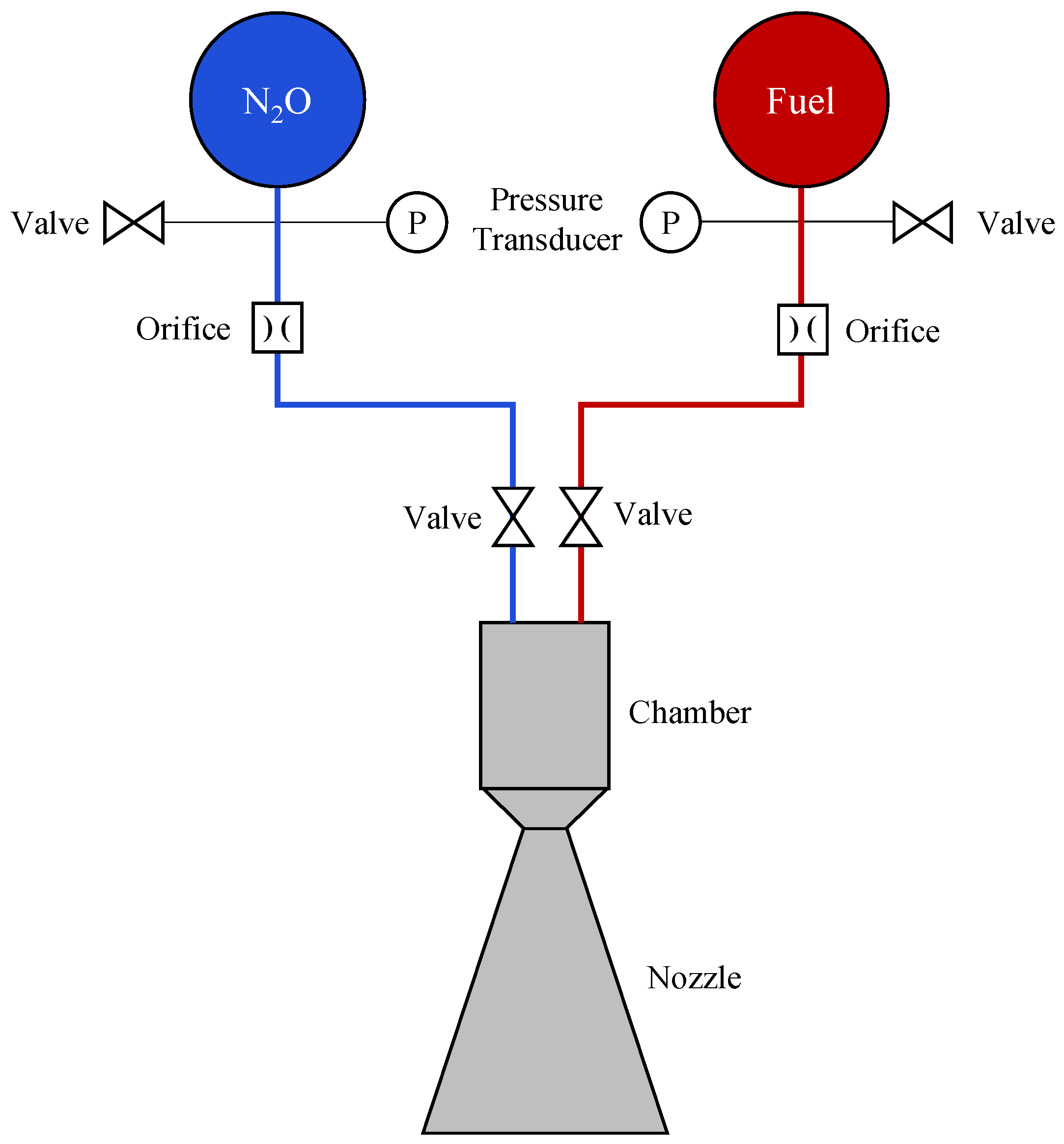

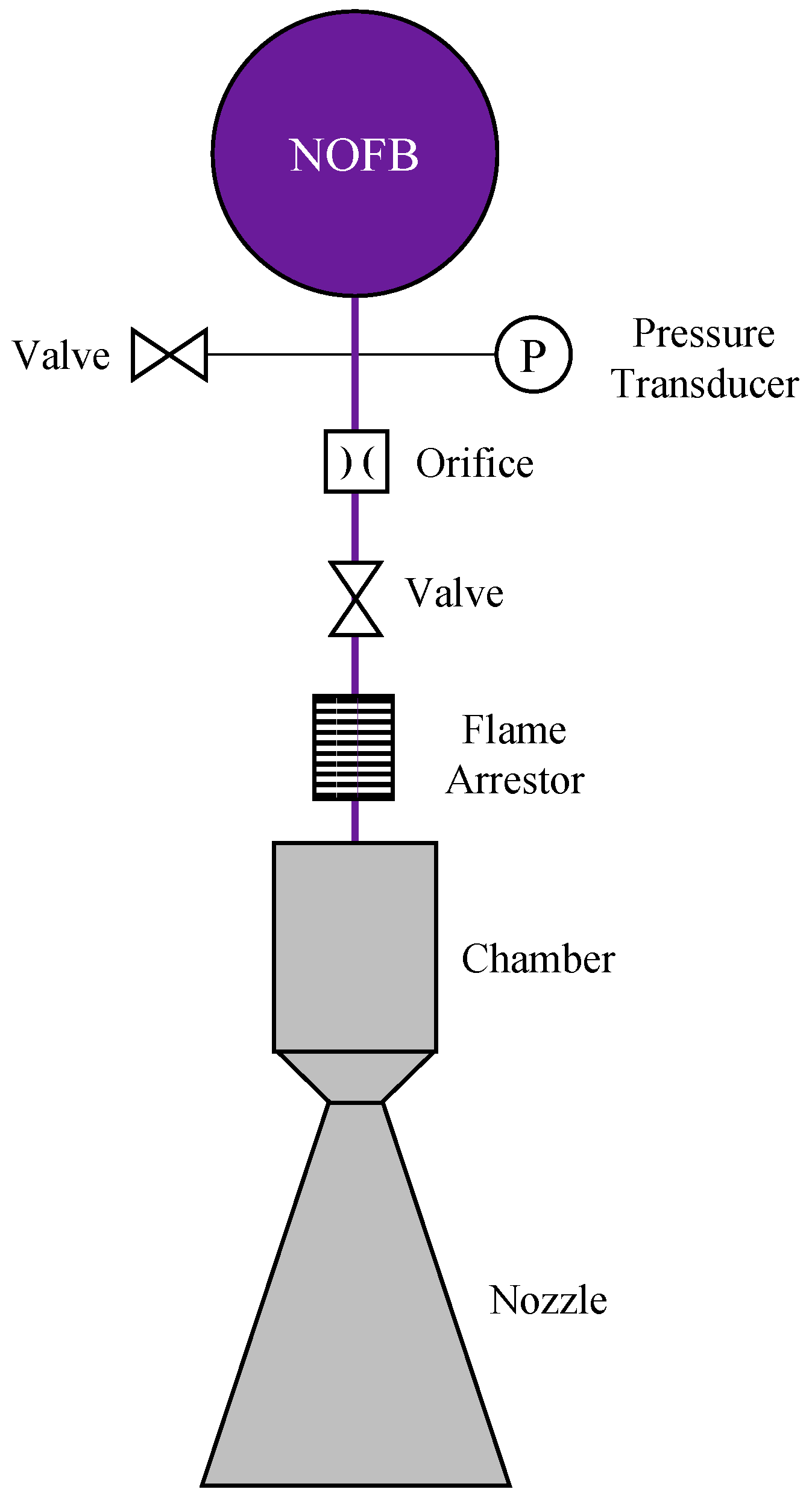

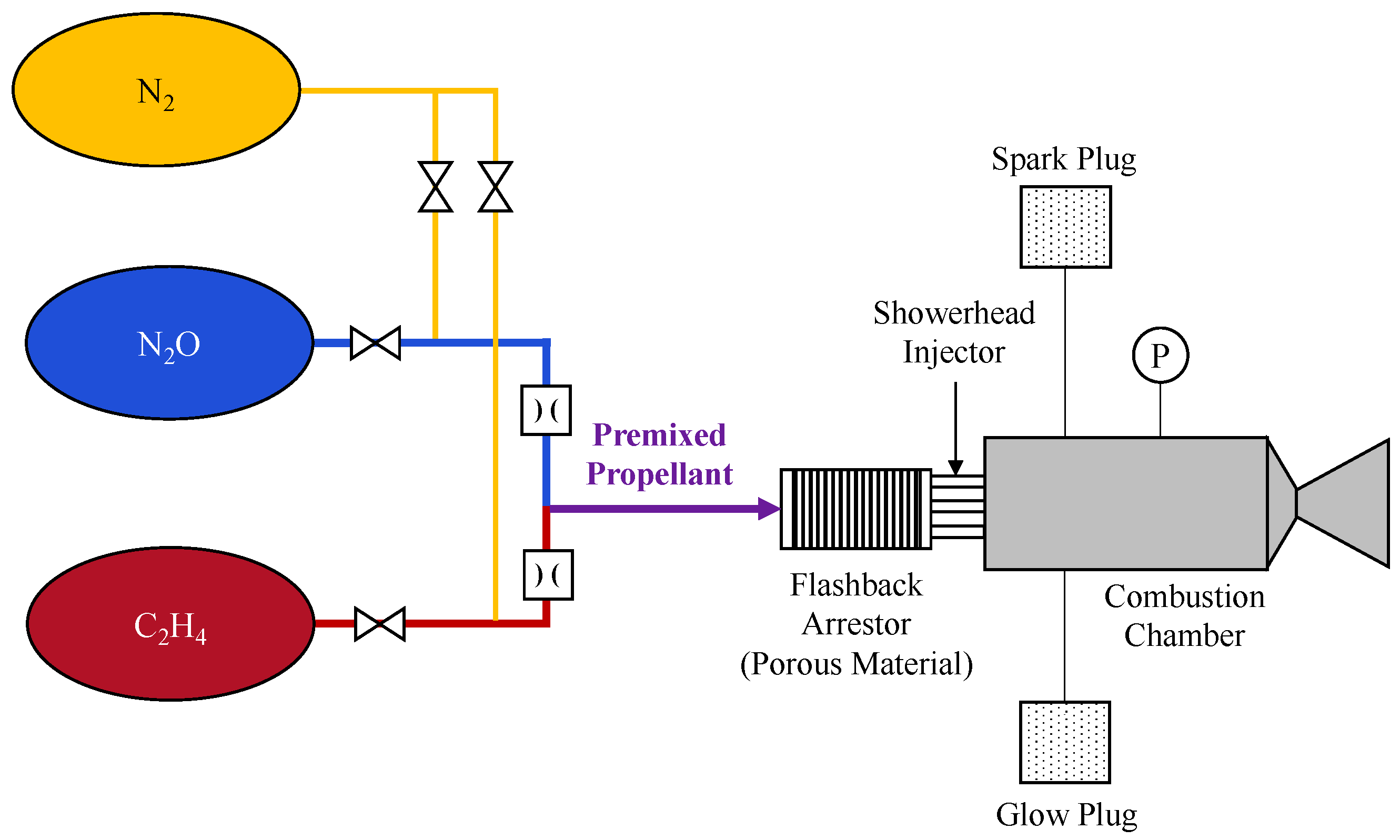

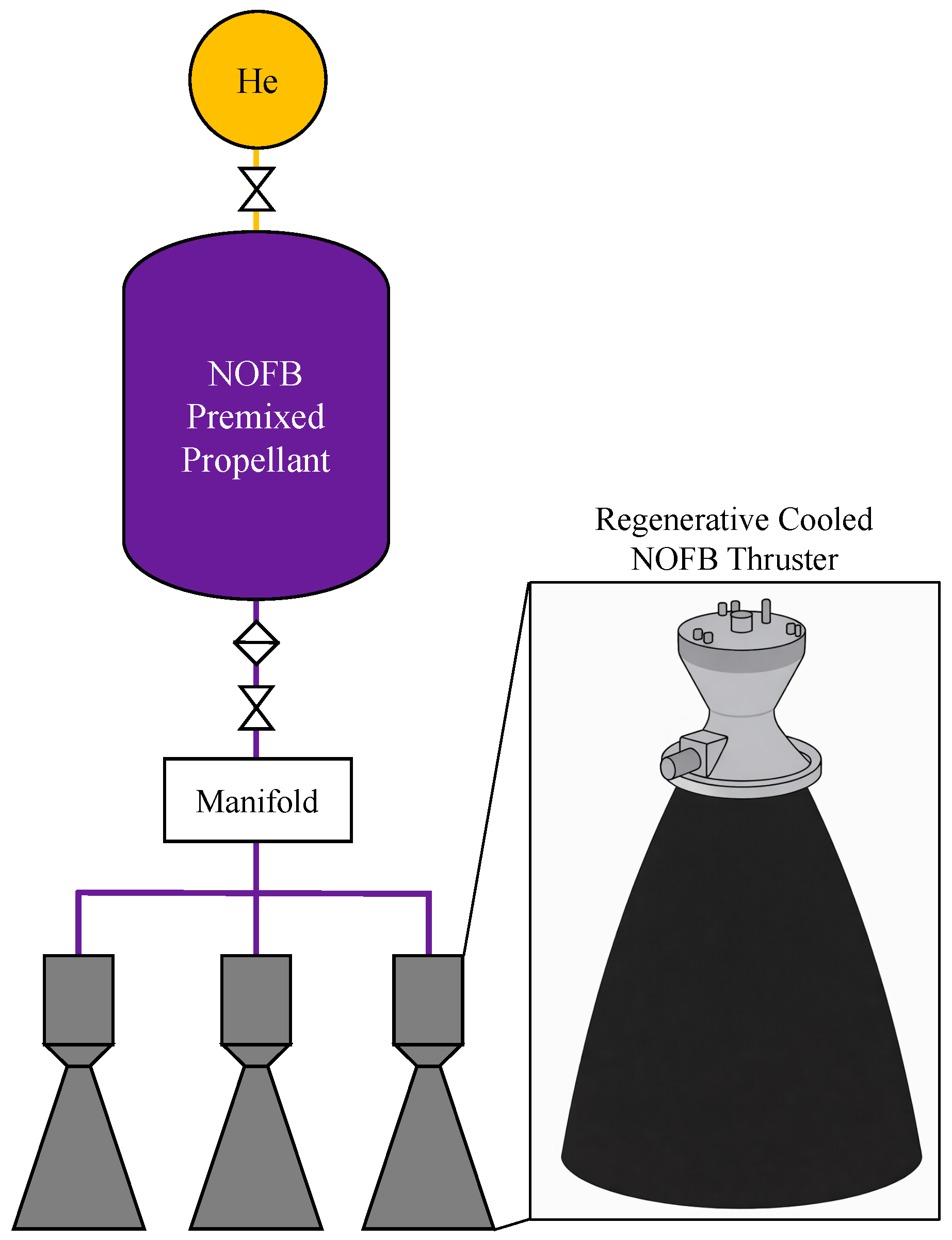

2. Nitrous Oxide-Hydrocarbon Propellant Combinations

2.1. Ethylene (C2H4) and Ethane (C2H6)

2.2. Ethanol (C2H5OH)

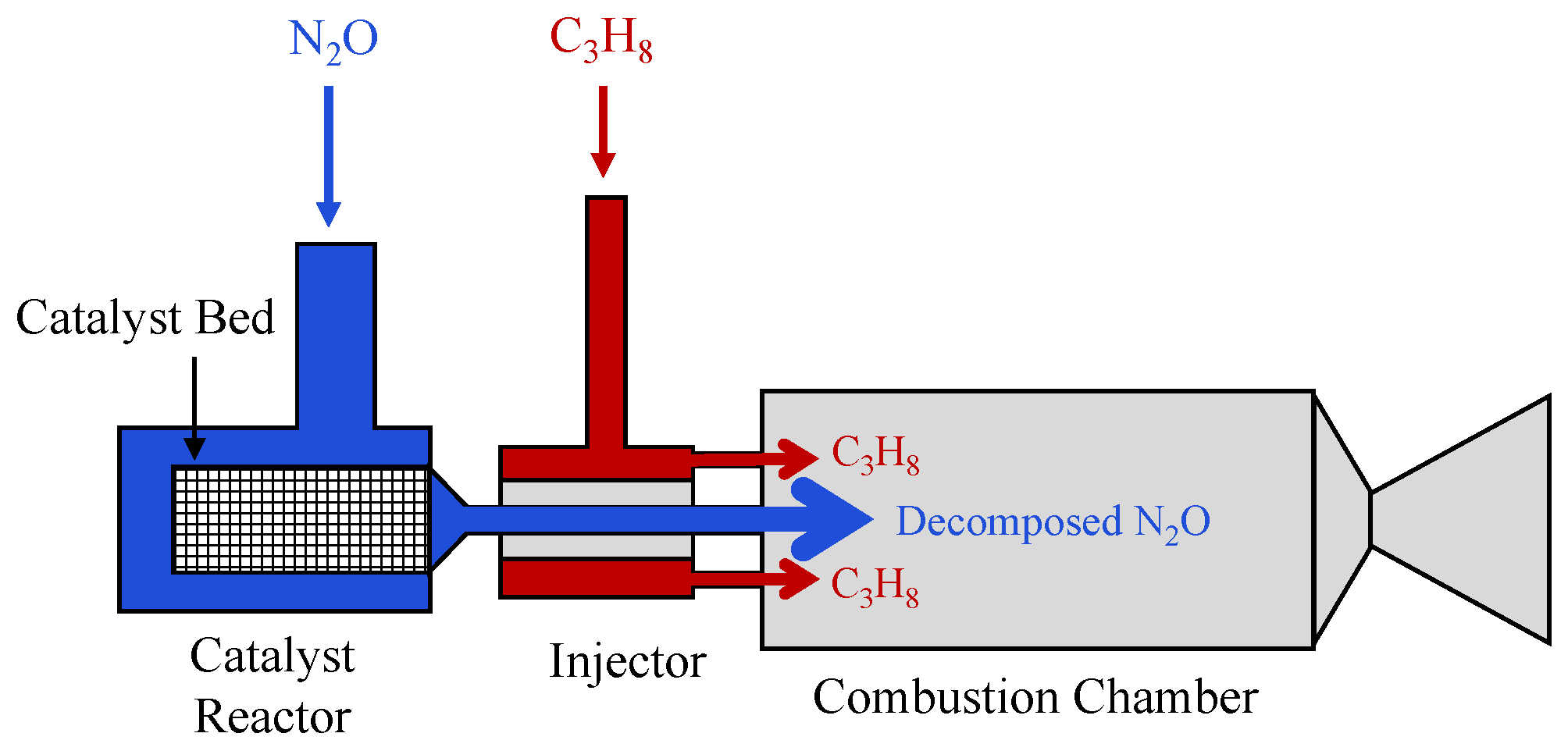

2.3. Propane (C3H8)

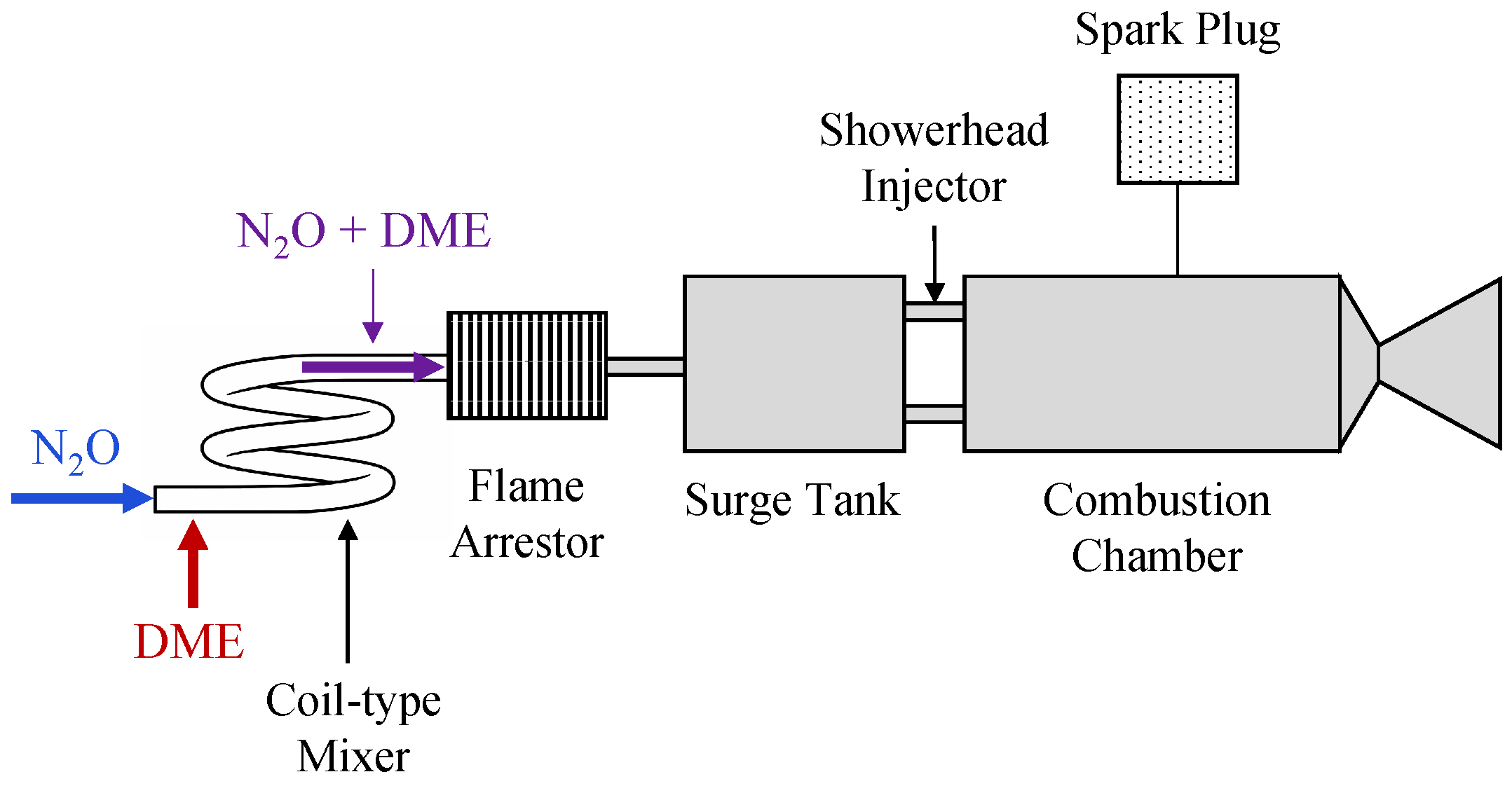

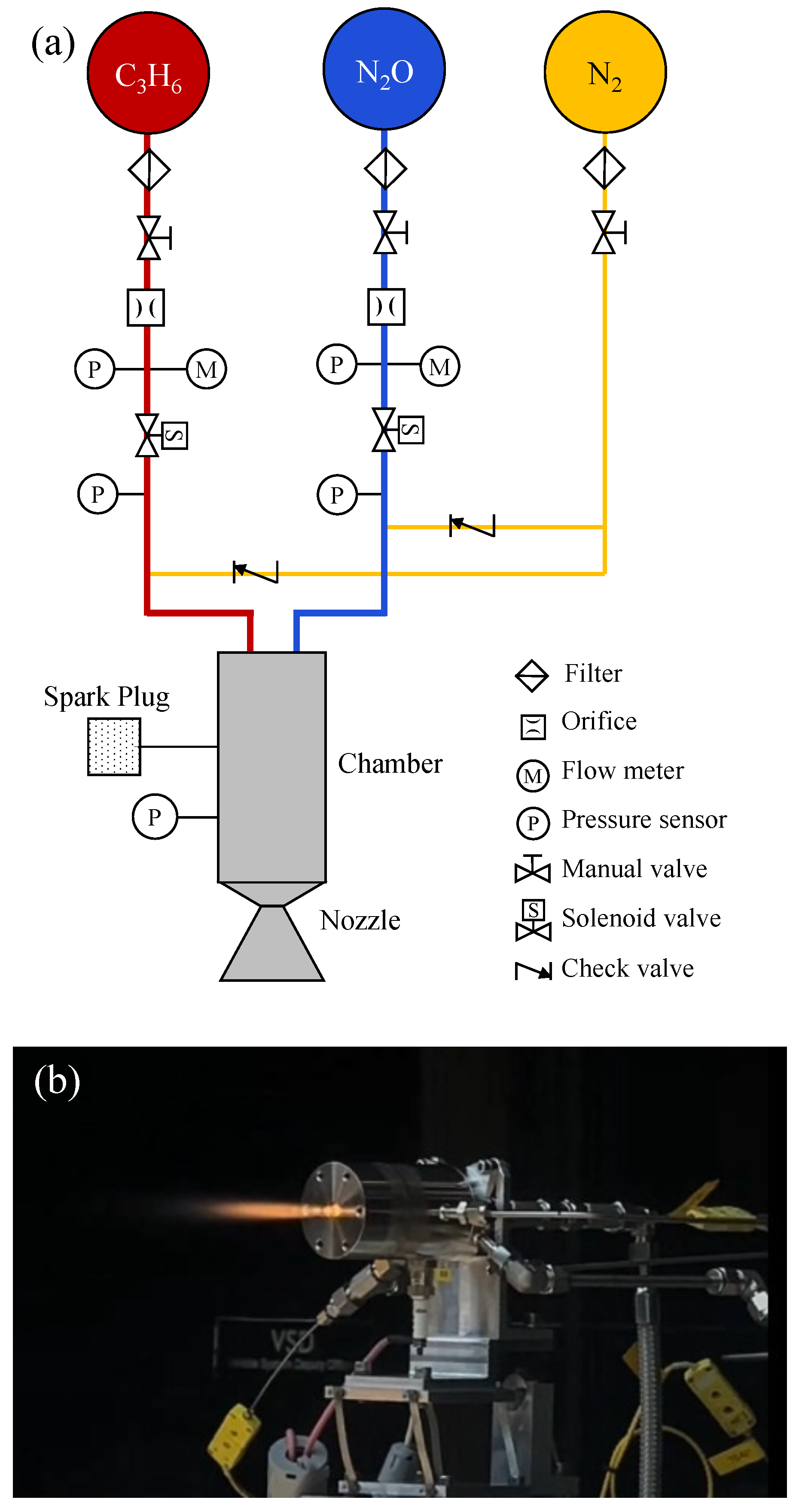

2.4. Other Fuels: Acetylene (C2H2), Methane (CH4), DME (CH3OCH3), and Propylene (C3H6)

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mayer, A.; Wieling, W. Green propulsion research at TNO the Netherlands. Trans. Aerosp. Res. 2018, 4, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosseir, A.E.S.; Cervone, A.; Pasini, A. Review of state-of-the-art green monopropellants: For propulsion systems analysts and designers. Aerospace 2021, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedenkopf, K. EU chemicals regulation: Extending its experimentalist REACH. In Extending Experimentalist Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, W.C. Toxicity assessment of hydrazine fuels. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1988, 59, A100–A106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sackheim, R.L.; Masse, R.K. Green propulsion advancement: Challenging the maturity of monopropellant hydrazine. J. Propuls. Power 2014, 30, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Patel, I.; Sharma, P. Green propellant: A study. Int. J. Latest Trends Eng. Technol. 2015, 6, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zakirov, V.; Sweeting, M.; Lawrence, T.; Sellers, J. Nitrous oxide as a rocket propellant. Acta Astronaut. 2001, 48, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacz, T. Nitrous oxide application for low-thrust and low-cost liquid rocket engine. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference for Aero-Space Sciences, Milano, Italy, 3–6 July 2017; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zakirov, V.; Sweeting, M.; Goeman, V.; Lawrence, T. Surrey research on nitrous oxide catalytic decomposition for space applications. In Proceedings of the 14th AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites, Logan, UT, USA, 21–24 August 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R. Safety and performance advantages of nitrous oxide fuel blends (NOFBX) propellants for manned and unmanned spaceflight applications. A Safer Space Safer World 2012, 699, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Pregger, T.; Schiller, G.; Cebulla, F.; Dietrich, R.U.; Maier, S.; Thess, A.; Lischke, A.; Monnerie, N.; Sattler, C.; Clercq, P.L.; et al. Future fuels—Analyses of the future prospects of renewable synthetic fuels. Energies 2019, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungas, G.; Vozoff, M.; Rishikof, B. NOFBX: A new non-toxic, Green propulsion technology with high performance and low cost. In Proceedings of the 63 International Astronautical Congress, Naples, Italy, 1–5 October 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, G.; Werling, L.; Gernoth, A.; Hagen, D. Development and Testing of a Nitrous Oxide–Propane Rocket Engine. In Proceedings of the 39th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Astrium Space Infrastructure, Huntsville, AL, USA, 20–23 July 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Haag, G.; Sweeting, M.; Richardson, G. Low cost propulsion development for small satellites at the surrey space centre. In Proceedings of the 13th Small Satellite Conference, Logan, UT, USA, 23–26 August 1999; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zakirov, V.; Sweeting, M.; Lawrence, T. An Update on Surrey Nitrous Oxide Catalytic Decomposition Research; SSC01-XI-2. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual Conference on Small Satellites, Logan, UT, USA, 13–14 August 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tarantini, V.; Risi, B.; Spina, R.; Orr, N.G.; Zee, R.E. Development of a nitrous oxide-based monopropellant thruster for small spacecraft. In Proceedings of the Small Satellites Systems and Services (4S) Symposium, Valletta, Malta, 30 May–3 June 2016; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Kim, T. N2O Decomposition on Ru/Si-doped Alumina Catalyst for Monopropellant Thruster. J. Propuls. Energy 2025, 5, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Sun, W.; Fang, J.; Li, M.; Cong, Y.; Yang, Z. Design and performance characterization of a sub-Newton N2O monopropellant thruster. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, F.; Ma, L.; Peng, S. Recent advances in catalytic decomposition of N2O on noble metal and metal oxide catalysts. Catal. Surv. Asia 2016, 20, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, G.D.; Gallo, G.; Mungiguerra, S.; Festa, G.; Savino, R. Design and testing of a monopropellant thruster based on N2O decomposition in Pd/Al2O3 pellets catalytic bed. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 180, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidei, T.P.; Kokorin, A.I.; Pillet, N.; Srukova, M.E.; Khaustova, E.S.; Shmurak, G.G.; Yaroshenko, N.T. The catalytic activity of metallic and deposited oxide catalysts in the decomposition of nitrous oxide. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 81, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendley, C.T., IV; Connell, T.L., Jr.; Wilson, D.; Young, G. Catalytic decomposition of nitrous oxide for use in hybrid rocket motors. J. Propuls. Power 2021, 37, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razus, D. Nitrous oxide: Oxidizer and promoter of hydrogen and hydrocarbon combustion. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 11329–11346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungas, G.; Fisher, D.; Vozoff, J.; Villa, M. NOFBXTM Single Stage to Orbit Mars Ascent Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 3–10 March 2012; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

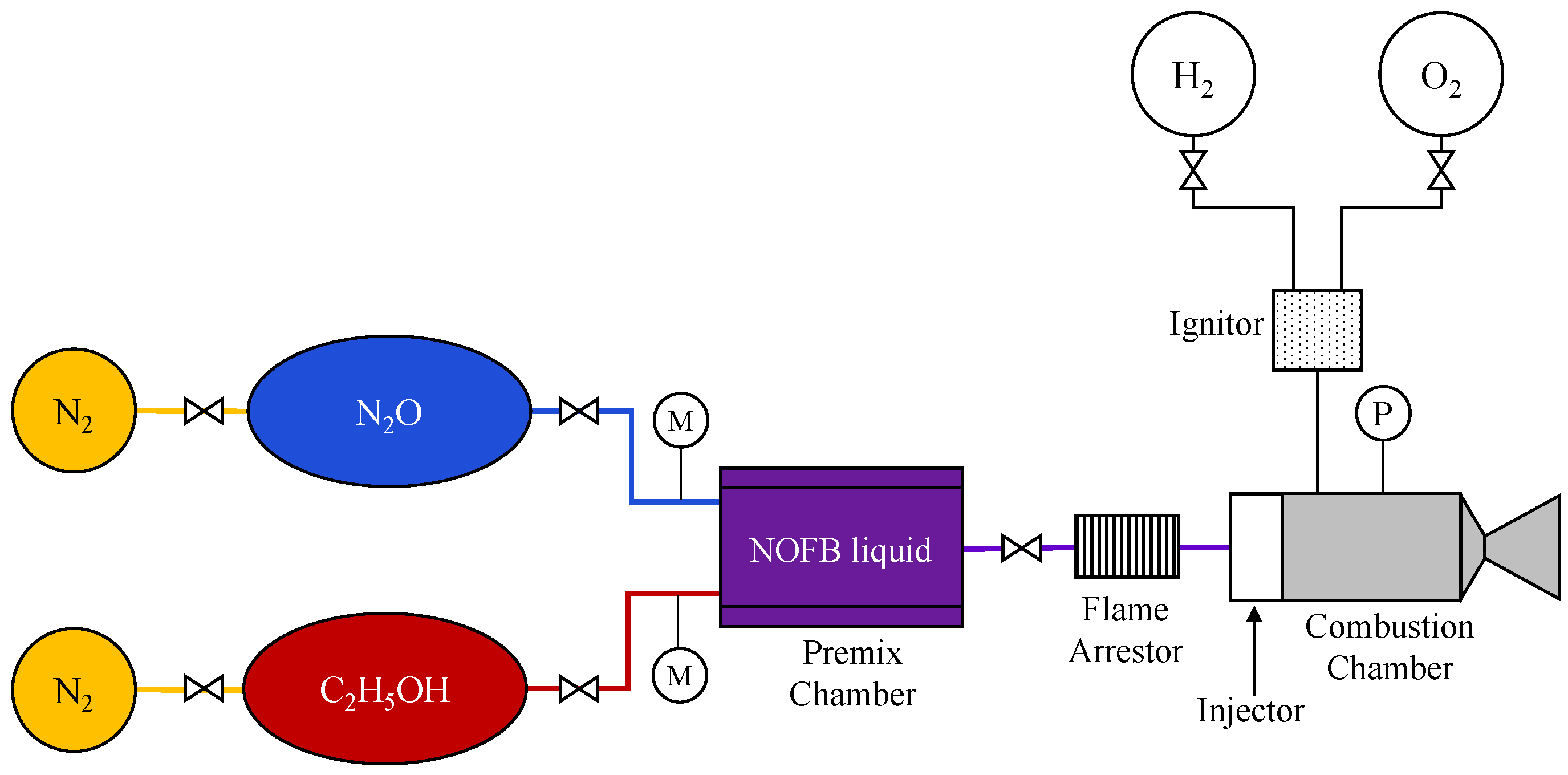

- Werling, L.; Lauck, F.; Freudenmann, D.; Röcke, N.; Ciezki, H.; Schlechtriem, S. Experimental investigation of the flame propagation and flashback behavior of a green propellant consisting of N2O and C2H4. J. Energy Power Eng. 2017, 11, 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thomas, G.; Oakley, G.; Bambrey, R. Fundamental studies of explosion arrester mitigation mechanisms. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 137, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, L.; Hörger, T.; Ciezki, H.; Schlechtriem, S. Experimental and Theoretical Analysis of the Combustion Efficiency and the Heat Loads on a N2O/C2H4 Green Propellant Combustion Chamber. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference for Aeronautics and Space Sciences, Madrid, Spain, 1–4 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, I.; Moore, E.; Macfarlane, J.; Watts, A.; Mayer, A.E.H.J. Testing of a novel nitrous-oxide and ethanol fuel blend. In Proceedings of the Space Propulsion Conference, Seville, Spain, 14–18 May 2018; pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, A.E.H.J.; Wieling, W.; Watts, A.; Poucet, M.; Waugh, I.; Macfarlane, J.; Valencia-Bel, F. European Fuel Blend development for in-space propulsion. In Proceedings of the Space Propulsion Conference, Seville, Spain, 14–18 May 2018; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M.; Launchbury, J.; Tompkins, S.; Pallota, B.; Hepburn, M.; Sanchez, J. Innovation at DARPA; Technical Report; Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA): Arlington, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, C. Nitrous Oxide Explosive Hazards; Technical Paper and Briefing Charts AFRL-RZ-ED-TP-2008-184; Air Force Research Laboratory (AFMC), AFRL/RZSP, Edwards Air Force Base: Edwards, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram, K.M.; Shreehan, M.M.; Olszewski, E.F. Ethylene. Kirk-Othmer Encycl. Chem. Technol. 2000, 10, 593–632. [Google Scholar]

- Douslin, D.R.; Harrison, R.H. Pressure, volume, temperature relations of ethylene. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1976, 8, 301–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, L.; Perakis, N.; Müller, S.; Hauck, A.; Ciezki, H.; Schlechtriem, S. Hot firing of a N2O/C2H4 premixed green propellant: First combustion tests and results. In Proceedings of the Space Propulsion Conference, Rome, Italy, 1–6 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Friend, D.G.; Ingham, H.; Fly, J.F. Thermophysical properties of ethane. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1991, 20, 275–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, L.K.; Hörger, T.; Manassis, K.; Grimmeisen, D.; Wilhelm, M.; Erdmann, C.; Ciezki, H.K.; Schlechtriem, S.; Richter, S.; Torsten, M.; et al. Nitrous oxide fuels blends: Research on premixed monopropellants at the german aerospace center (DLR) since 2014. In Proceedings of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Propulsion and Energy Forum, Online, 24–26 August 2020; p. 3807. [Google Scholar]

- Hageman, M.D.; Hopper, D.R.; Knadler, M. Detonation limits and velocity deficits of CH4, C2H4, C2H6 and C3H8 with N2O in a small diameter tube. In Proceedings of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Propulsion and Energy 2019 Forum, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 August 2019; p. 3952. [Google Scholar]

- Shimamori, H.; Fessenden, R.W. Mechanism of thermal electron attachment in N2O and N2O–hydrocarbon mixtures in the gas phase. J. Chem. Phys. 1978, 68, 2757–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, H. Laminar burning velocities of C2H4/N2O flames: Experimental study and its chemical kinetics mechanism. Combust. Flame 2019, 202, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Hsu, C.H.; Lin, P.H.; Chen, C.H. Thermal effect and oxygen-enriched effect of N2O decomposition on soot formation in ethylene diffusion flames. Fuel 2022, 329, 125430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, R.; Xu, S.; Gong, X. Theoretical Study on the Gas-Phase Oxidation Mechanism of Ethylene by Nitrous Oxide. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2022, 47, e202200082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, H.Y.; Feng, J.C.; Zheng, D. Experimental investigation of auto-ignition of ethylene-nitrous oxide propellants in rapid compression machine. Fuel 2021, 288, 119688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, Y.; Liao, C.; Tang, C.; Zhou, C.W.; Huang, Z. The auto-ignition boundary of ethylene/nitrous oxide as a promising monopropellant. Combust. Flame 2020, 221, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, R.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Pan, F.; Xie, L. Studies on the flame propagation characteristic and thermal hazard of the premixed N2O/fuel mixtures. Def. Technol. 2020, 16, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Q.; Ma, H.H.; Shen, Z.W.; Pan, J. A comparative study of the explosion behaviors of H2 and C2H4 with air, N2O and O2. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 119, 103260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangalore Venkatesh, P.; Meyer, S.E.; Bane, S.P.; Grubelich, M.C. Deflagration-to-detonation transition in nitrous oxide/oxygen-fuel mixtures for propulsion. J. Propuls. Power 2019, 35, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, H.; Wang, C. Detonation velocity behavior and scaling analysis for ethylene-nitrous oxide mixture. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 127, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, C.; Kick, T.; Methling, T.; Braun-Unkhoff, M.; Riedel, U. Ethene/dinitrogen oxide-a green propellant to substitute hydrazine: Investigation on its ignition delay time and laminar flame speed. In Proceedings of the 26th International Colloquium on the Dynamics of Explosions and Reactive Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 30 July–4 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Janzer, C.; Richter, S.; Naumann, C.; Methling, T. “Green propellants” as a hydrazine substitute: Experimental investigations of ethane/ethene-nitrous oxide mixtures and validation of detailed reaction mechanism. Counc. Eur. Aerosp. Soc. Space J. 2022, 14, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, C.; Kick, T.; Methling, T.; Braun-Unkhoff, M.; Riedel, U. Ethene/nitrous oxide mixtures as green propellant to substitute hydrazine: Reaction mechanism validation. Int. J. Energetic Mater. Chem. Propuls. 2020, 19, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perakis, N.; Werling, L.; Ciezki, H.; Schlechtriem, S. Numerical Calculation of Heat Flux Profiles in a N2O/C2H4 Premixed Green Propellant Combustor using an Inverse Heat Conduction Method. In Proceedings of the Space Propulsion Conference, Rome, Italy, 2–6 May 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Werling, L.; Jooß, Y.; Wenzel, M.; Ciezki, H.K.; Schlechtriem, S. A premixed green propellant consisting of N2O and C2H4: Experimental analysis of quenching diameters to design flashback arresters. Int. J. Energetic Mater. Chem. Propuls. 2018, 17, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, L.; Müller, S.; Hauk, A.; Ciezki, H.K.; Schlechtriem, S. Pressure drop measurement of porous materials: Flashback arrestors for a N2O/C2H4 premixed green propellant. In Proceedings of the 52nd AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 25–27 July 2016; p. 5094. [Google Scholar]

- Werling, L.; Gernoth, A.; Schlechtriem, S. Investigation of the Combustion and Ignition Process of a Nitrous Oxide/Ethene Fuel Blend. In Proceedings of the Space Propulsion Conference, Cologne, Germany, 19–22 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Perakis, N.; Hochheimer, B.; Werling, L.; Gernoth, A.; Schlechtriem, S. Development of an Experimental Demonstrator Unit Using Nitrous Oxide/Ethylene Premixed Bipropellant for Satellite Applications. In Proceedings of the Space Propulsion Conference 2014, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Lampoldshausen, Cologne, Germany, 19–22 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Werling, L.; Perakis, N.; Hochheimer, B.; Ciezki, H.; Schlechtriem, S. Experimental investigations based on a demonstrator unit to analyze the combustion process of a nitrous oxide/ethene premixed green bipropellant. In Proceedings of the 5th Council of European Aerospace Societies Air & Space Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 7–11 September 2015; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Werling, L.; Bätz, P. Parameters influencing the characteristic exhaust velocity of a nitrous oxide/ethene green propellant. J. Propuls. Power 2022, 38, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, M.; Werling, L.; Lauck, F.; Goos, E.; Wischek, J.; Besel, Y.; Valencia-Bel, F. High Performance Propellant Development-Overview of Development Activities Regarding Premixed, Green N2O/C2H6 Monopropellants; Paper ID 93. In Proceedings of the 8th Space Propulsion Conference Estoril, Portugal, Estoril, Portugal, 9–13 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mungas, G.; Vozoff, M.; Rishikof, B.; Strack, D.; London, A.; Fryer, J.; Buchanan, L. NOFBX® Monopropulsion Overview. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual FAA Commercial Space Transportation Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 9–10 February 2011; Volume 626, pp. 755–8819. [Google Scholar]

- SpaceNews. Vast selects Impulse Space for Haven-1 Space Station Propulsion. 2023. Available online: https://spacenews.com/vast-selects-impulse-space-for-haven-1-space-station-propulsion/ (accessed on 14 January 2026).

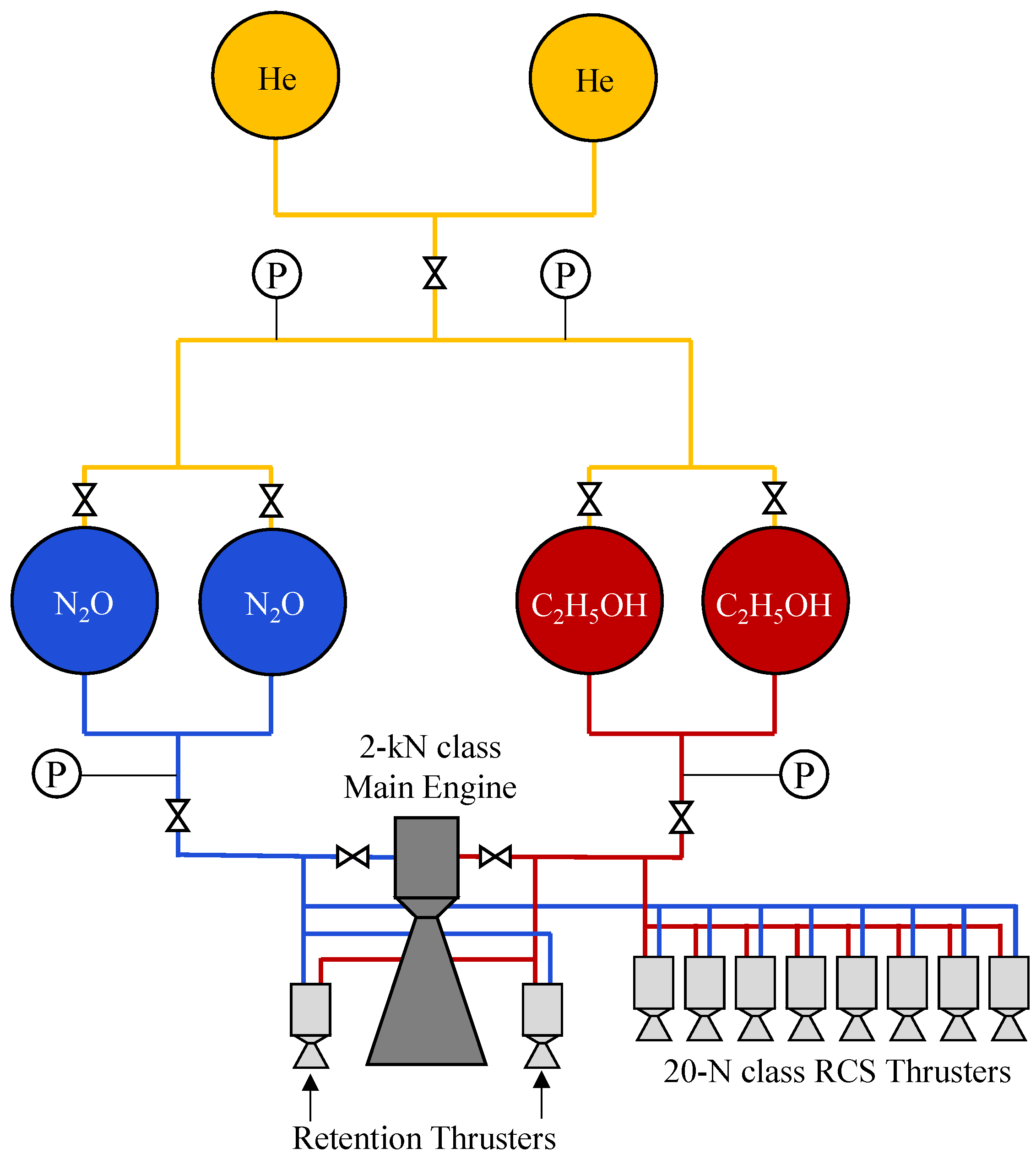

- Tokudome, S.; Yagishita, T.; Goto, K.; Suzuki, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Daimoh, Y. An Experimental Study of an N2O/Ethanol Propulsion System with 2 kN Thrust Class BBM. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. Aerosp. Technol. Jpn. 2021, 19, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, F.A.d.S.; Hinckel, J.N.; Rocco, E.M.; Schlingloff, H. Modeling and analysis of a LOX/Ethanol liquid rocket engine. J. Aerosp. Technol. Manag. 2018, 10, e3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, G.; Watts, D. Nitrous oxide and ethanol propulsion concepts for a crew space vehicle. In Proceedings of the 43rd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 8–11 July 2007; p. 5462. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, H.E.; Penoncello, S.G. A fundamental equation for calculation of the thermodynamic properties of ethanol. Int. J. Thermophys. 2004, 25, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Son, M.; Koo, J. Atomization and combustion characteristics of ethanol/nitrous oxide at various momentum flux ratios. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 2770–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, J.; Yu, M.; Lee, K.; Koo, J. Visualization of Transient Ignition Flow-field in a 50 N Scale N2O/C2H5OH Thruster. J. Korean Soc. Propuls. Eng. 2014, 18, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokudome, S.; Yagishita, T.; Habu, H.; Shimada, T.; Daimou, Y. Experimental study of an N2O/ethanol propulsion system. In Proceedings of the 43rd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 8–11 July 2007; p. 5464. [Google Scholar]

- Tokudome, S.; Goto, K.; Yagishita, T.; Suzuki, N.; Yamamoto, T. An experimental study of a nitrous oxide/ethanol (NOEL) propulsion system. In Proceedings of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Propulsion and Energy 2019 Forum, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 August 2019; p. 4429. [Google Scholar]

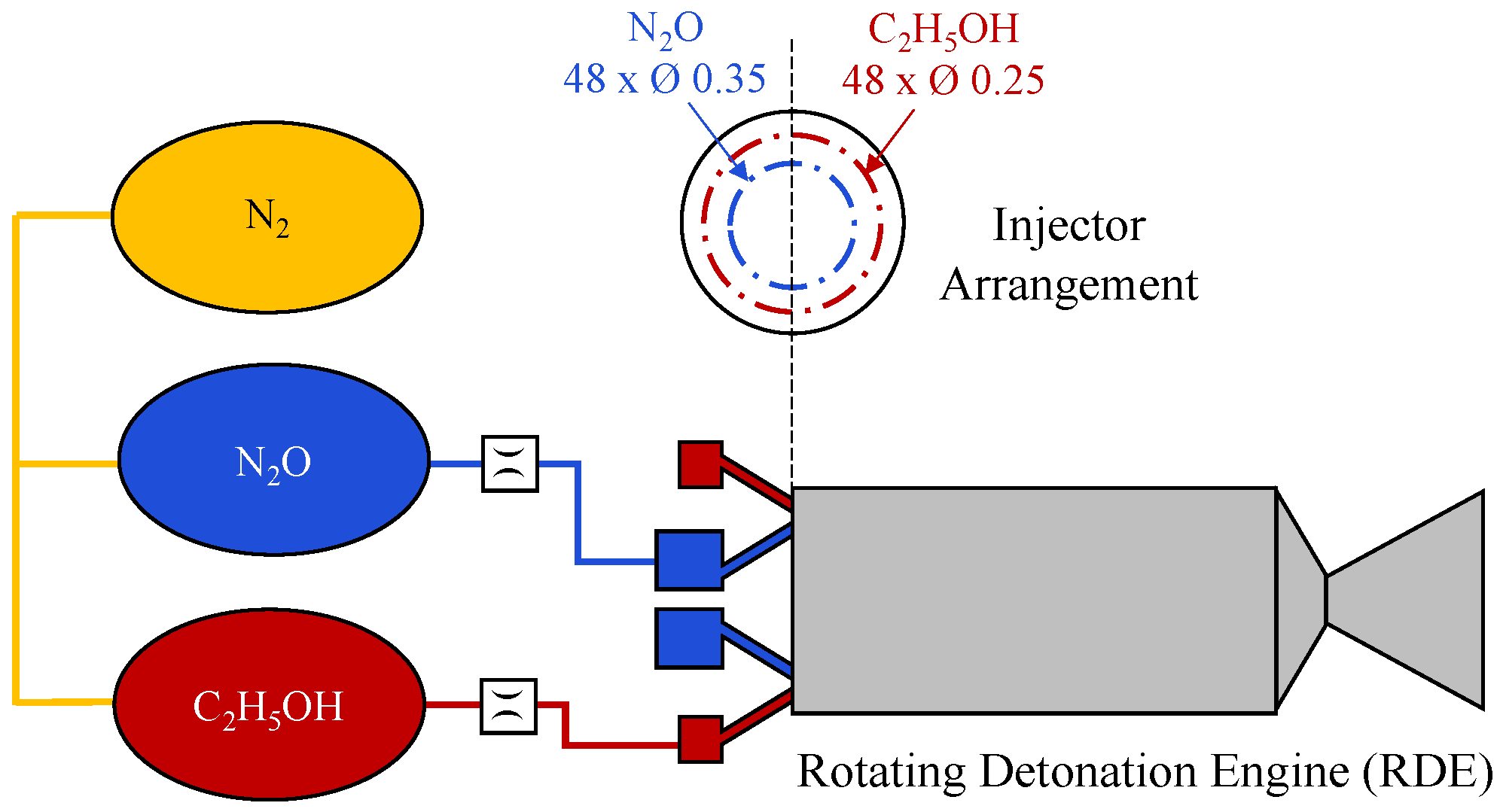

- Sato, T.; Nakata, K.; Ishihara, K.; Itouyama, N.; Matsuoka, K.; Kasahara, J.; Kawasaki, A.; Nakata, D.; Eguchi, H.; Uchiumi, M.; et al. Combustion structure of a cylindrical rotating detonation engine with liquid ethanol and nitrous oxide. Combust. Flame 2024, 264, 113443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, K.; Sato, T.; Kimura, T.; Nakajima, K.; Nakata, K.; Itouyama, N.; Kawasaki, A.; Matsuoka, K.; Matsuyama, K.; Kasahara, J.; et al. Nitrous Oxide/Ethanol Cylindrical Rotating Detonation Engine for Sounding Rocket Space Flight. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2025, 62, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

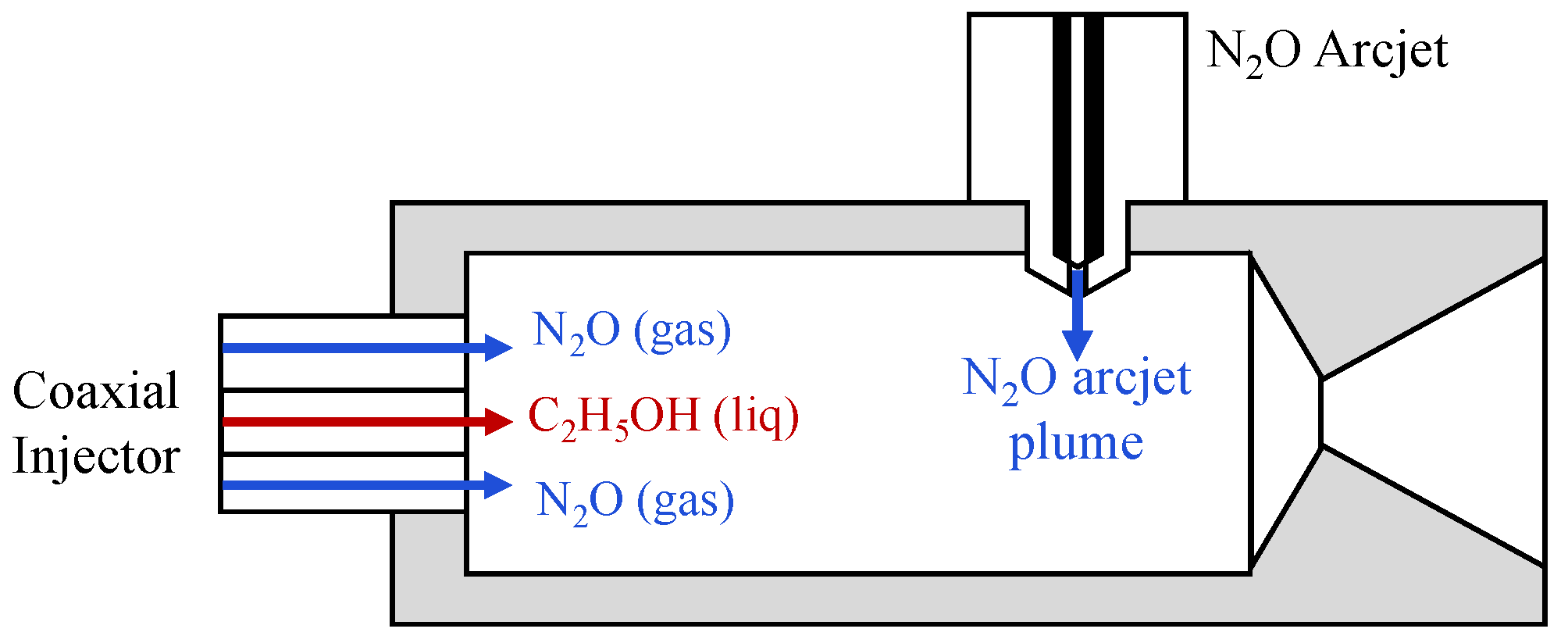

- Kakami, A.; Ishibashi, T.; Ideta, K.; Tachibana, T. One-Newton class thruster using arc discharge assisted combustion of nitrous oxide/ethanol bipropellant. Vacuum 2014, 110, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakami, A.; Egawa, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Tachibana, T. Plasma-assisted combustion of N2O/Ethanol propellant for Space Propulsion. In Proceedings of the 46th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Nashville, TN, USA, 25–28 July 2010; p. 6806. [Google Scholar]

- Youngblood, S.H. Design and Testing of a Liquid Nitrous Oxide and Ethanol Fueled Rocket Engine. ProQuest Number: 1606125. Master’s Thesis, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, NM, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Phillip, J.; Youngblood, S.; Grubelich, M.; Saul, W.V.; Hargather, M.J. Development and testing of a nitrous-oxide/ethanol bi-propellant rocket engine. In Proceedings of the 52nd AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 25–27 July 2016; p. 5092. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, E.W.; McLinden, M.O.; Wagner, W. Thermodynamic properties of propane. III. A reference equation of state for temperatures from the melting line to 650 K and pressures up to 1000 MPa. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2009, 54, 3141–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.; Wilhoit, R.C.; Zwolinski, B.J. Ideal gas thermodynamic properties of ethane and propane. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1973, 2, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdy, R. Nitrous oxide/hydrocarbon fuel advanced chemical propulsion: DARPA contract overview. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Thermal and Fluids Analysis Workshop (TFAWS 2006), College Park, ML, USA, 7–11 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, O.A.; Papas, P.; Dreyer, C.B. Hydrogen-and C1–C3 Hydrocarbon-Nitrous Oxide Kinetics in Freely Propagating and Burner-Stabilized Flames, Shock Tubes, and Flow Reactors. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2010, 182, 252–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, O.A.; Papas, P.; Dreyer, C. Laminar burning velocities for hydrogen-, methane-, acetylene-, and propane-nitrous oxide flames. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2009, 181, 917–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubkov, K.A.; Parfenov, M.V.; Kharitonov, A.S. Gas-phase oxidation of a propane–propylene mixture by nitrous oxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 14157–14162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanyam, M.; Moser, M.; Sharp, D. Catalytic ignition of nitrous oxide with propane/propylene mixtures for rocket motors. In Proceedings of the 41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Tucson, AZ, USA, 10–13 July 2005; p. 3919. [Google Scholar]

- Tiliakos, N.; Tyll, J.; Herdy, R.; Sharp, D.; Moser, M.; Smith, N. Development and testing of a nitrous oxide/propane rocket engine. In Proceedings of the 37th Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 8–11 July 2001; p. 3258. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, S.; Knop, T.; Engelen, S. Experimental Evaluation of a Green Bi-Propellant Thruster for Small Satellite Applications; SSC16-X-8. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Small Satellite Conference on Small Satellites, Hyperion Technologies B.V., Delft, The Netherlands, 6–11 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ABC News. Queensland Space Startup Valiant Space Eyes Rocket Launch as SpaceX Looms Large. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-11-17/qld-space-rockets-valiant-space-start-up-company-spacex/101660100 (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Pässler, P.; Hefner, W.; Buckl, K.; Meinass, H.; Meiswinkel, A.; Wernicke, H.J.; Ebersberg, G.; Müller, R.; Bässler, J.; Behringer, H.; et al. Acetylene. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aldous, K.; Bailey, B.; Rankin, J. Burning velocity of the premixed nitrous-oxide/acetylene flame and its influence on burner design. Anal. Chem. 1972, 44, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spravka, J.J.; Jorris, T.R. Current hypersonic and space vehicle flight test instrumentation challenges. In Proceedings of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Flight Testing Conference, Dallas, TX, USA, 22–26 June 2015; p. 3224. [Google Scholar]

- Neill, T.; Judd, D.; Veith, E.; Rousar, D. Practical uses of liquid methane in rocket engine applications. Acta Astronaut. 2009, 65, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, D.G.; Ely, J.F.; Ingham, H. Thermophysical properties of methane. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1989, 18, 583–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, O.; Miller, J.; Dreyer, C.; Papas, P. Characterization of hydrocarbon/nitrous oxide propellant combinations. In Proceedings of the 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 7–10 January 2008; p. 999. [Google Scholar]

- Mével, R.; Shepherd, J. Ignition delay-time behind reflected shock waves of small hydrocarbons–nitrous oxide (–oxygen) mixtures. Shock Waves 2015, 25, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Lehman, T.; Grana, R.; Seshadri, K.; Williams, F. The structure and extinction of nonpremixed methane/nitrous oxide and ethane/nitrous oxide flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2013, 34, 2147–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, B.N.; Lin, P.H.; Li, Y.H.; Honra, J.P. Effect of plasma assisted combustion on emissions of a premixed nitrous oxide fuel blend. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.Y.; Kim, T. Design and Performance Evaluation of CH4/N2O Premixed Propellant Thruster. SSRN 2025, SSRN:5237487. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5237487 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Semelsberger, T.A.; Borup, R.L.; Greene, H.L. Dimethyl ether (DME) as an alternative fuel. J. Power Sources 2006, 156, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Tachibana, T. Burning velocities of dimethyl ether (DME)–nitrous oxide (N2O) mixtures. Fuel 2018, 217, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Hayashi, S.; Yano, Y.; Kakami, A. Influence of Injector for Performance of N2O/DME Bipropellant Thruster. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. Aerosp. Technol. Jpn. 2018, 16, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakami, A.; Kuranaga, A.; Yano, Y. Premixing-type liquefied gas bipropellant thruster using nitrous oxide/dimethyl ether. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 94, 105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.; Zwolinski, B.J. Ideal gas thermodynamic properties of ethylene and propylene. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1975, 4, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SatNews. Dawn Aerospace’s Smallsat Green Propellant Thruster Proves Itself on-orbit with D-Orbit’s ION Space Tug. 2021. Available online: https://news.satnews.com/2021/05/04/dawn-aerospaces-smallsat-green-propellant-thruster-proves-itself-on-orbit-with-d-orbits-ion-space-tug/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Jo, H.; Lee, A.; Kang, H. Ammonia-based storable bipropellant (N2O/NH3) thruster utilizing dual-mode plasma ignition for enhanced propellant flexibility. Fuel 2026, 406, 136893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, R.; Komizu, K.; Tsuji, A.; Miwa, T.; Fukada, M.; Yokobori, S.; Soeda, K.; Kamps, L.; Nagata, H. Fuel regression characteristics of axial-injection end-burning hybrid rocket using nitrous oxide. J. Propuls. Power 2022, 38, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Kamps, L.; Hirai, S.; Carmicino, C.; Harunori, N. Prediction of the fuel regression-rate in a HDPE single port hybrid rocket fed by liquid nitrous oxide. Combust. Flame 2024, 259, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ugolini, V.M.P.; Jung, E.; Kwon, S. Demonstration of Polyethylene Nitrous Oxide Catalytic Decomposition Hybrid Thruster with Dual-Catalyst Bed Preheated by Hydrogen Peroxide. Aerospace 2025, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, S.A. Additively manufactured acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene–nitrous-oxide hybrid rocket motor with electrostatic igniter. J. Propuls. Power 2015, 31, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanaro, A.; Piazzullo, D.; Tortorici, D.; Ingenito, A.; Allocca, L. Green rocket propulsion: Overview of nitrous oxide applications with emphasis on hybrid systems. Fuel 2026, 406, 137036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Hydrazine | MMH/NTO | N2O | N2O/C3H8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [s] | 230 | 292 | 192 | 312 |

| c* [m/s] | 937 | 1790 | 1066 | 1595 |

| [K] | 561 | 3250 | 1775 | 3120 |

| Toxicity | Toxic | Toxic | Non-toxic | Non-toxic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jung, E.; Jung, E.S.; Lee, M. Nitrous Oxide-Hydrocarbon Liquid Propellants for Space Propulsion: Premixed and Non-Premixed Systems. Aerospace 2026, 13, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010104

Jung E, Jung ES, Lee M. Nitrous Oxide-Hydrocarbon Liquid Propellants for Space Propulsion: Premixed and Non-Premixed Systems. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Eunwoo, Eun Sang Jung, and Minwoo Lee. 2026. "Nitrous Oxide-Hydrocarbon Liquid Propellants for Space Propulsion: Premixed and Non-Premixed Systems" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010104

APA StyleJung, E., Jung, E. S., & Lee, M. (2026). Nitrous Oxide-Hydrocarbon Liquid Propellants for Space Propulsion: Premixed and Non-Premixed Systems. Aerospace, 13(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010104