Study on Certification-Driven Fault Detection Threshold Optimization for eVTOL Dual-Motor-Driven Rotor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Modeling

2.1. BLDC Motor Mathematical Model Test Method

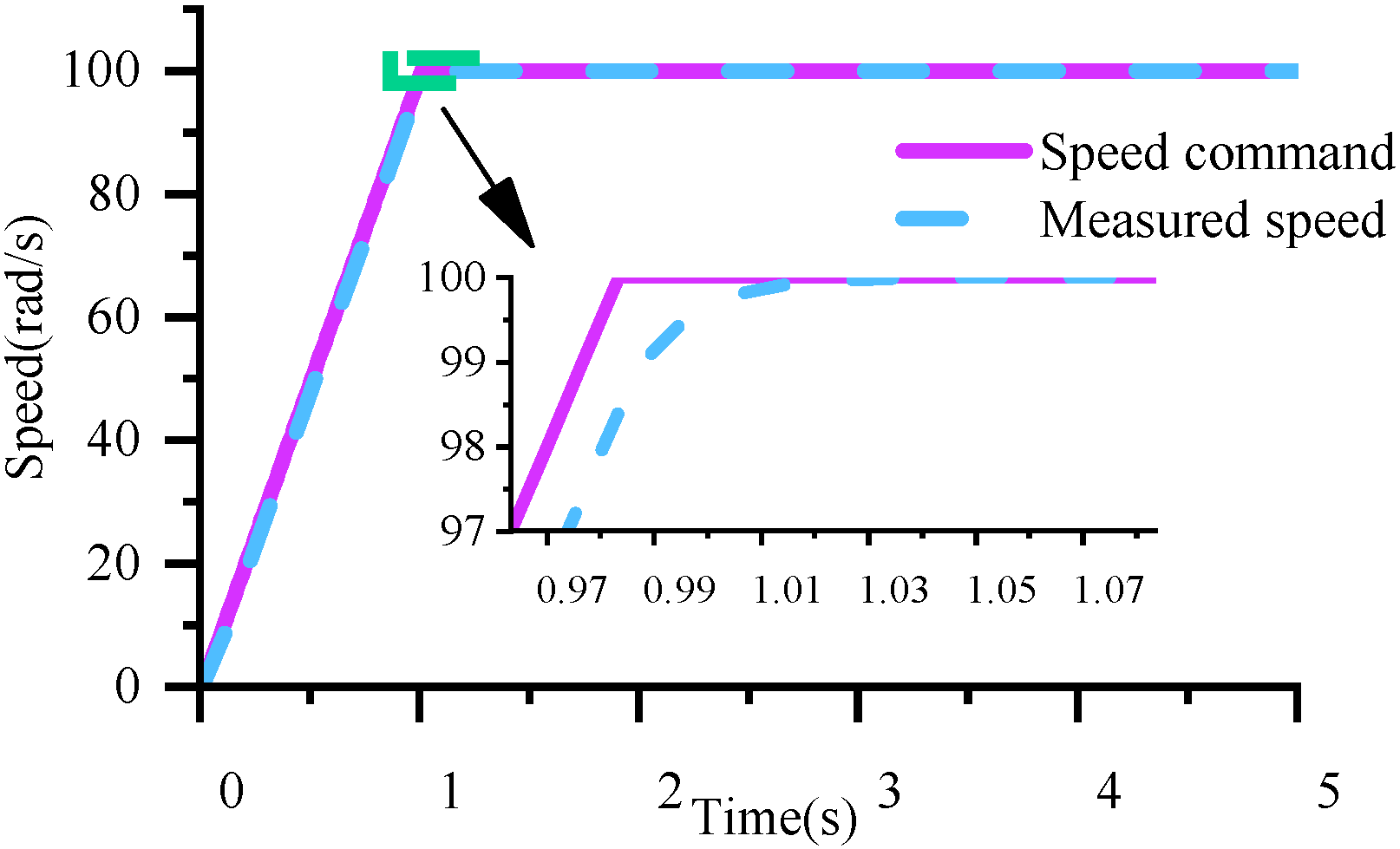

2.2. Speed PI Closed-Loop Control

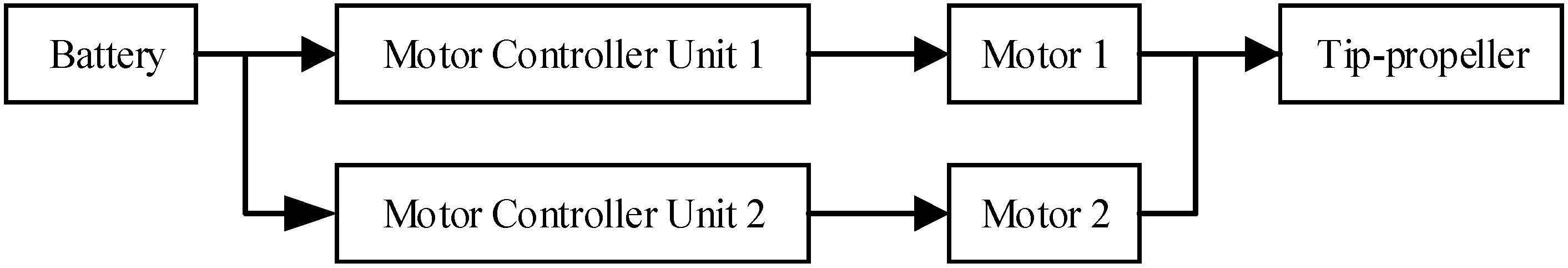

3. Redundancy Architecture Design

3.1. System Architecture

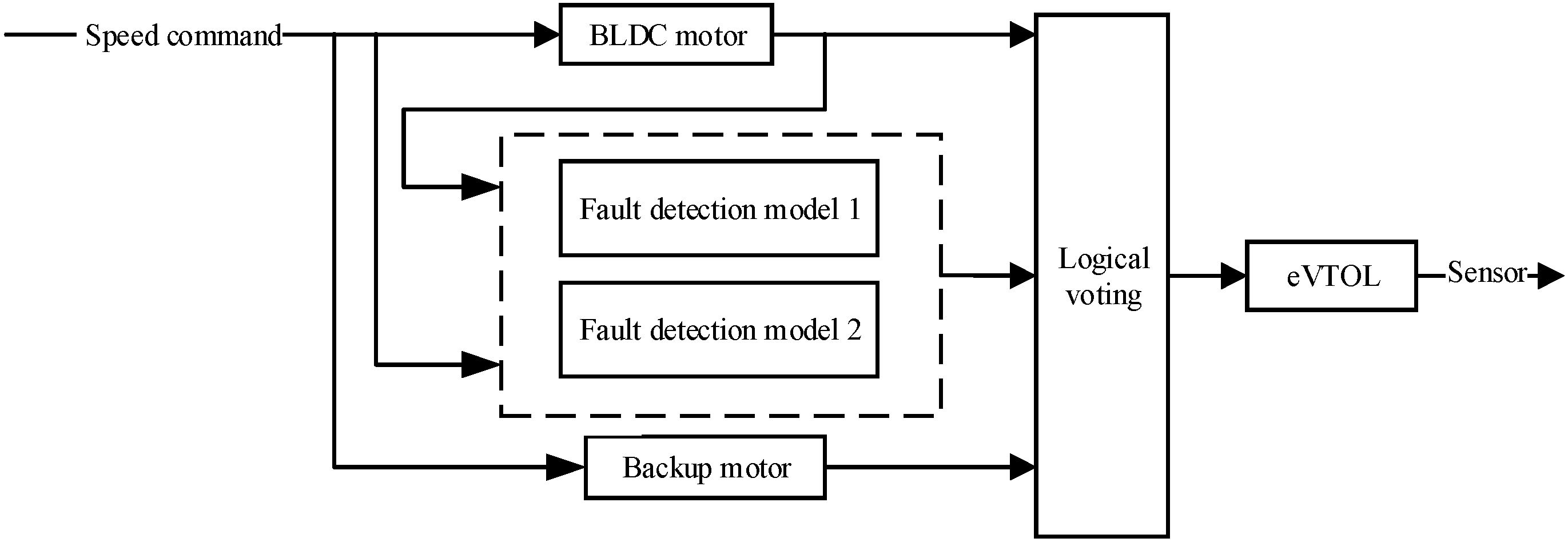

3.2. Fault Detection Design

- Kalman filter

- 2.

- Robust Observer

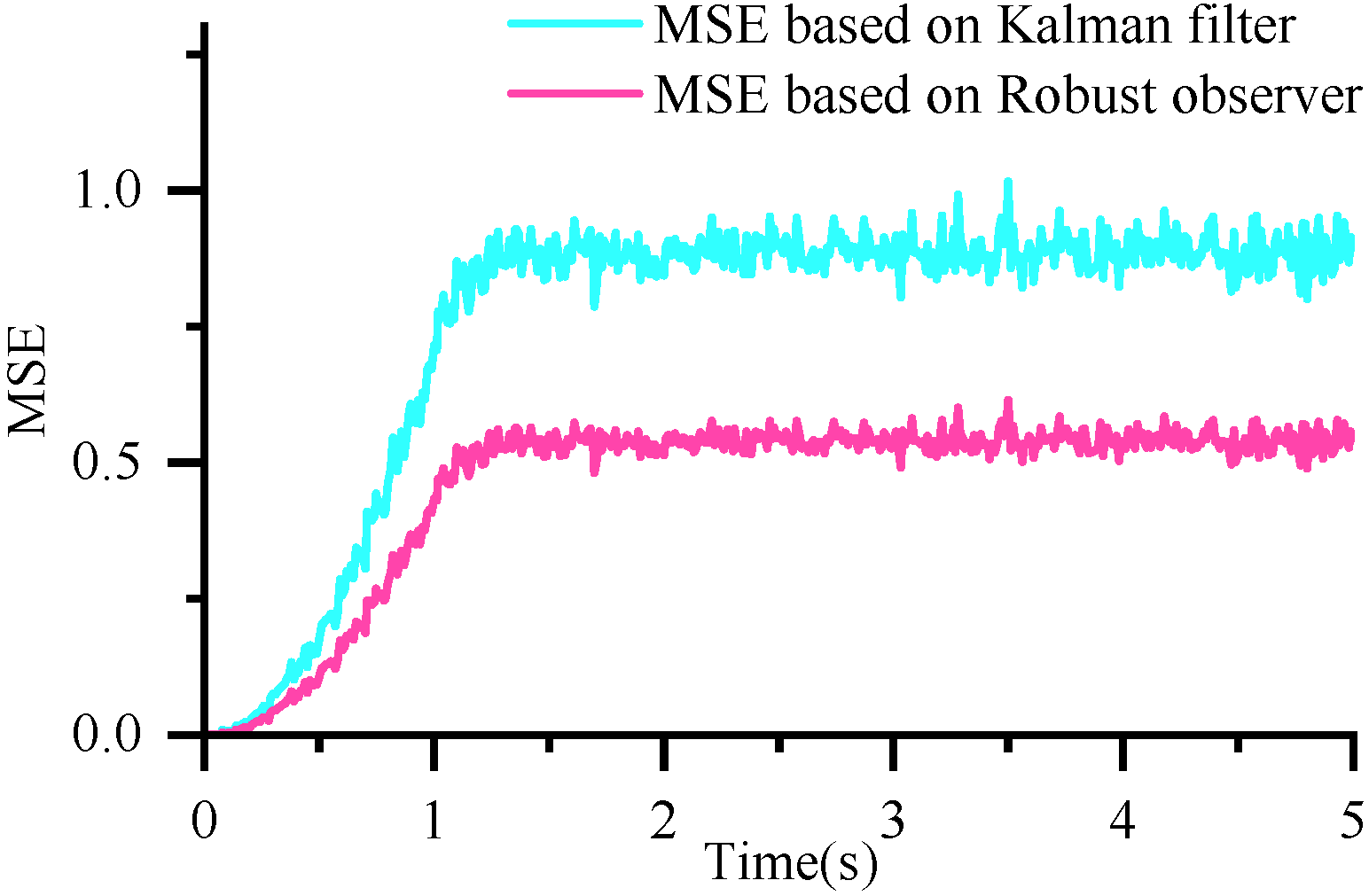

3.3. Comparison of Detection Methods

4. Threshold Optimization Approach

4.1. Optimization Goal

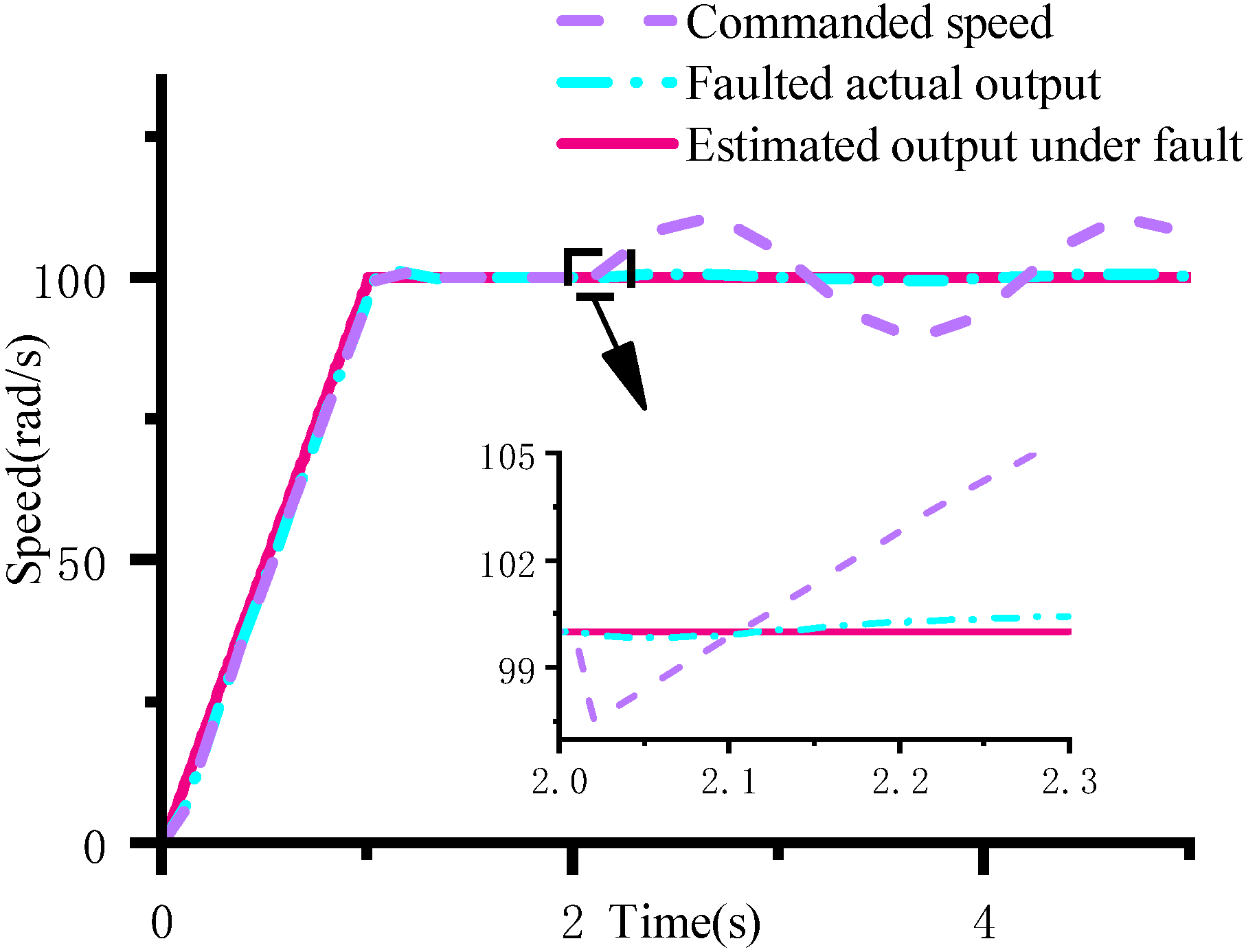

- Rapidity: This refers to the ability of the system to quickly and accurately identify faults under ideal dynamic conditions during the switching process between the primary and standby systems. In simulation, the rapidity of fault detection results can be evaluated by monitoring the changes in parameters such as the actual speed, estimated speed, and residual of the motor system.

- Reliability: A confusion matrix is used to evaluate the false positive and missed detection rates of the model’s detection results, calculating the probability of occurrence of different failure modes to verify system stability. This method can quantitatively analyze the accuracy and robustness of the detection model under various operating conditions.

4.2. Detection Model Evaluation

4.3. Detection Logic Analysis

- The reliability calculation for fault detection based on a single Kalman filter is as follows, and the corresponding reliability diagram of false positives and false negatives is shown in Figure 9

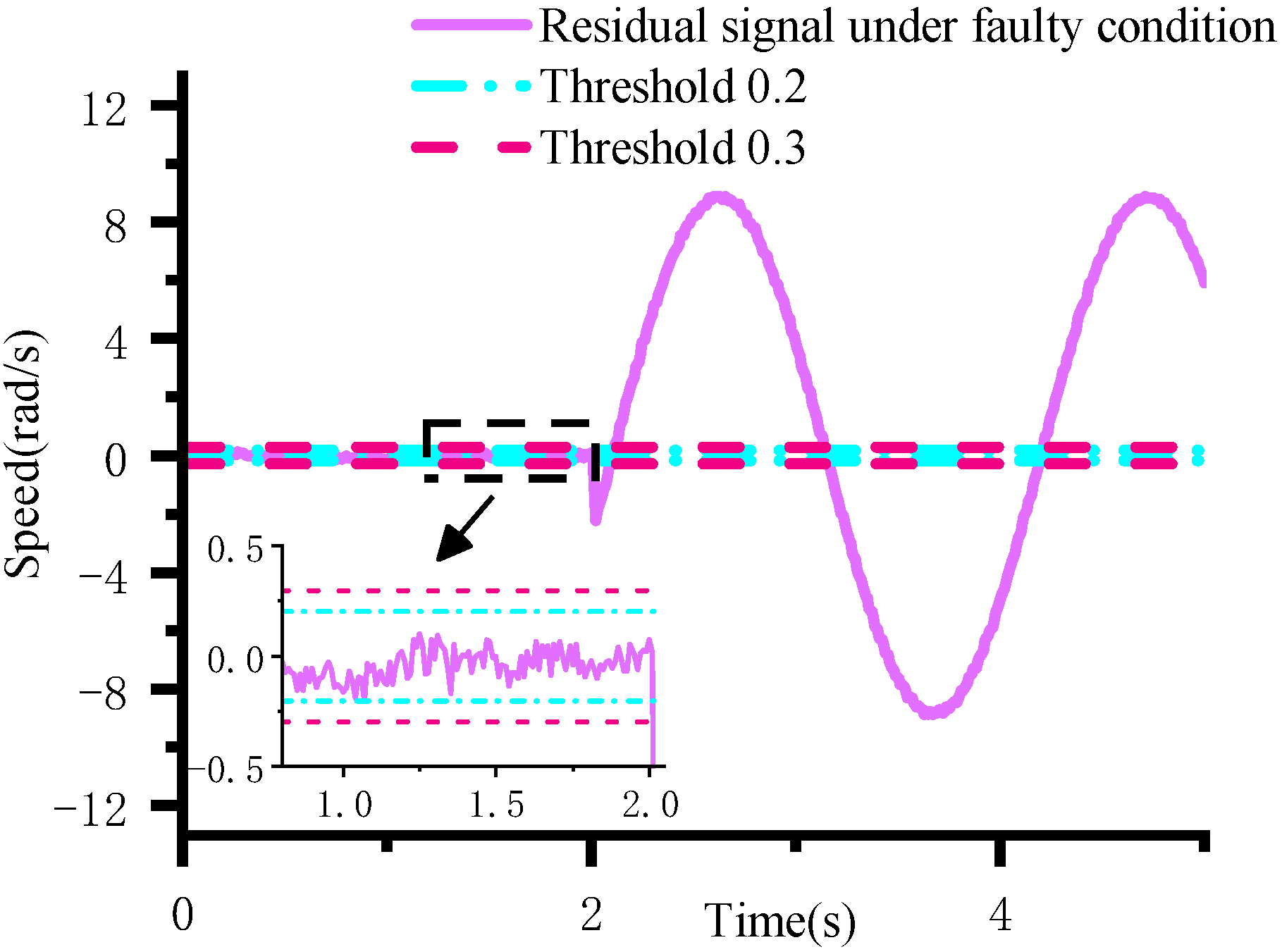

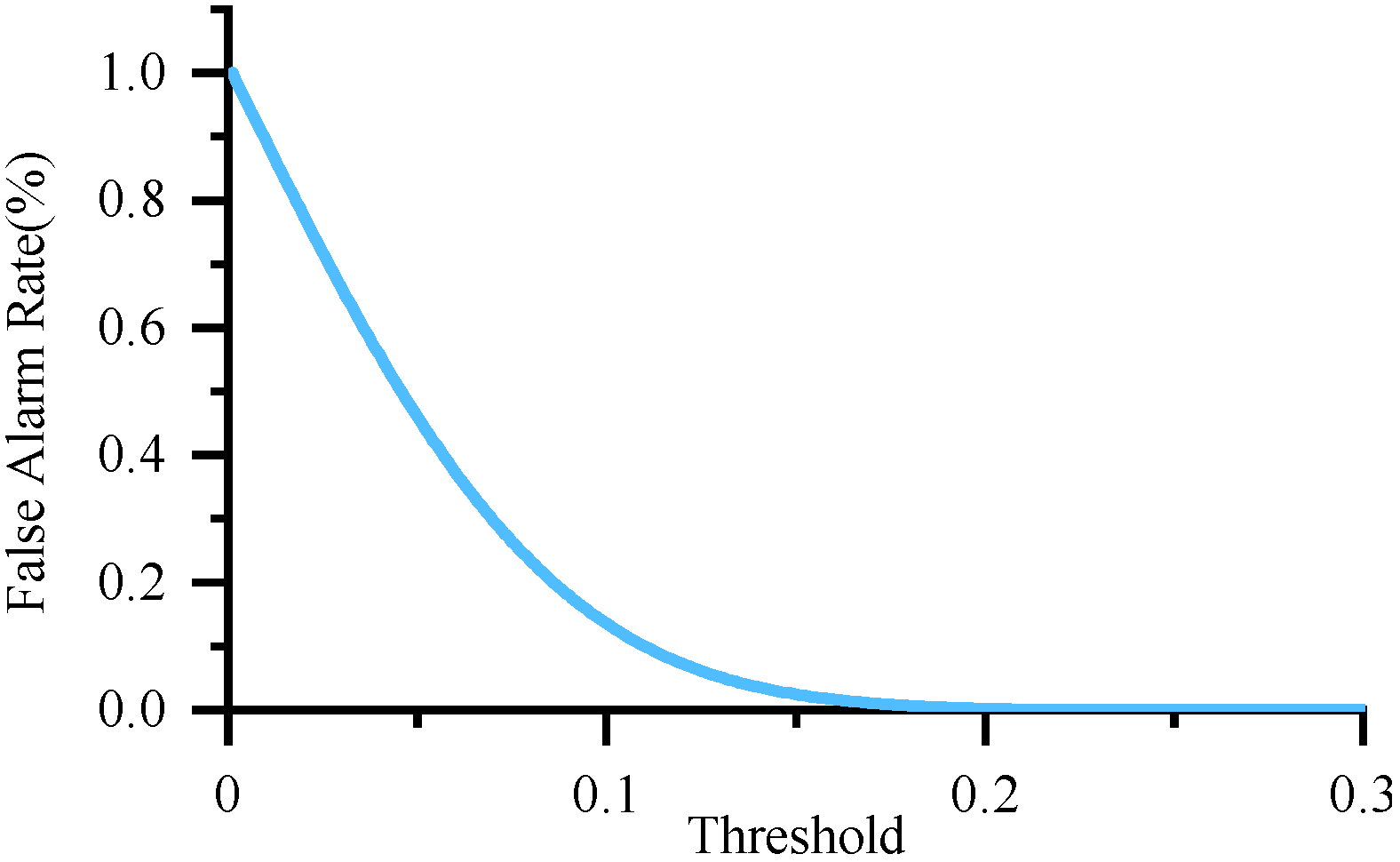

- The reliability calculation for fault detection based on a single robust observer is as follows, and the corresponding reliability diagram of false positives and false negatives is shown in Figure 10.

- Based on the combination of the Kalman filter and robust observer, the reliability calculation of the alarm detection mechanism (OR voting) is as follows, and the corresponding reliability diagram of false positives and false negatives is shown in Figure 11.

- Based on the combination of the Kalman filter and robust observer, the reliability calculation of the simultaneous alarm detection mechanism (AND voting) is as follows, and the corresponding reliability diagram of false positives and false negatives is shown in Figure 12.

4.4. System Reliability Analysis

5. Simulation Analysis

5.1. Fault Detection Based on Kalman Filter

5.2. Fault Detection Based on Robust Observer

5.3. Analysis of Threshold Optimization

5.4. Failure Probability Calculation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Motor friction and viscous losses coefficient B (N m sec) | 0.15 |

| Voltage constant Ke (V rad/s) | 1.2 |

| Torque SI unit conversion constant c (lb − ft Nm) | 0.7374 |

| Armature resistance Ra (Ohms) | 0.6187 |

| Inertia of the high speed drive components drive system gear ratio r squared Jr2 (slug ft2) | 30 |

| Armature inductance La (millihenry mH) | ≈0 |

| Rotor rotational moment of inertia Ir (slug ft2) | 101.968 |

References

- Su, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.Y. eVTOL performance analysis: A review from control perspectives. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 4877–4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, R.; Torres, L.; Pérez, P. Review of methods for diagnosing faults in the stators of BLDC motors. Processes 2023, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, L.; Zolghadri, A.; Goupil, P.; Simon, P. Oscillatory failure case detection for new generation airbus aircraft: A model-based challenge. In Proceedings of the 47th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Cancun, Mexico, 9–11 December 2008; IEEE Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1249–1254. [Google Scholar]

- El Mekki, A.; Saad, K.B. Diagnosis based on a sliding mode observer for an inter-turn short circuit fault in brushless dc motors. Rev. Roum. Des Sci. Technol. Electrotech. Energétique 2018, 63, 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Moseler, O.; Isermann, R. Application of model-based fault detection to a brushless DC motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2000, 47, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Jiang, B.; Yan, X.-G.; Mao, Z. Incipient fault detection for traction motors of high-speed railways using an interval sliding mode observer. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 2703–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.; Abedi, M.; Mohammad Hosseini, S. Classification of multiple electromechanical faults in BLDC motors using neural networks and optimization algorithms. Res. Technol. Electr. Ind. 2023, 2, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenicke, P.; Ghosh, D.; Muhandes, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bauer, C.; Kallo, J.; Willich, C. Power management control and delivery module for a hybrid electric aircraft using fuel cell and battery. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 244, 114445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.D.; Badewa, O.A.; Mohammadi, A.; Vatani, M.; Ionel, D.M. Fault tolerant electric machine concept for aircraft propulsion with pm rotor and dc current stator dual-stage excitation. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Oshawa, ON, Canada, 29 August–1 September 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 607–611. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Second Publication of Proposed Means of Compliance with the Special Condition VTOL:No:MOC-2 SC-VTOL; European Union Aviation Safety Agency: Cologne, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–94.

- Pavel, M.D. Understanding the control characteristics of electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft for urban air mobility. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 125, 107143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, E.S.; Aretskin-Hariton, E.; Ingraham, D.; Gray, J.S.; Schnulo, S.L.; Chin, J.; Falck, R.; Hall, D. Multidisciplinary optimization of an electric quadrotor urban air mobility aircraft. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation Forum, Reston, VA, USA, 15–19 June 2020; AIAA Aviation Forum: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; p. 3176. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, B.; Datta, A. Analysis of a permanent magnet synchronous motor coupled to a flexible rotor for electric VTOL. In Proceedings of the Annual Forum Proceedings-American Helicopter Society International, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 14–17 May 2018; American Helicopter Society International: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Withrow-Maser, S.; Malpica, C.; Nagami, K. Impact of handling qualities on motor sizing for multirotor aircraft with urban air mobility missions. In Proceedings of the Vertical Flight Society’s 77th Annual Forum & Technology Display, Fairfax, VA, USA, 10–14 May 2021; The Vertical Flight Society: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2021; pp. 1653–1675. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J. Fault Detection of an actuator with dual type motors and one common motion sensor. Electronics 2022, 11, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Tan, K.K.; Lee, T.H. Fault diagnosis and fault-tolerant control in linear drives using the Kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 59, 4285–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.M. Enhancement of robustness in observer-based fault detection. Int. J. Control. 1994, 59, 955–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Seiler, P.J. Certification analysis for a model-based UAV fault detection system. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, National Harbor, MD, USA, 13–17 January 2014; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2014; p. 610. [Google Scholar]

- Kotikalpudi, A.; Danowsky, B.P.; Seiler, P.J. Reliability analysis for small unmanned air vehicle with algorithmic redundancy. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2020; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; p. 739. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, R.L.; Filho, A.C.L.; Ramos, J.G.S.; Nascimento, T.P.; Brito, A.V. A novel approach for speed and failure detection in brushless DC motors based on chaos. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 66, 8751–8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpica, C.; Withrow-Maser, S. Handling qualities analysis of blade pitch and rotor speed controlled eVTOL quadrotor concepts for urban air mobility. In Proceedings of the Vertical Flight Society International Powered Lift Conference 2020, San Jose, CA, USA, 21–23 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

| True States | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | Faulty | ||

| FDI Logic | Nominal | True Negative | Missed Detection |

| Faulty | False Alarm | True Positive | |

| Kalman Filter | Robust Observer | |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal threshold | 0.287 | 0.284 |

| False alarm rate | 0.015% | 0.012% |

| Missed detection rate | 0.018% | 0.013% |

| Detection Logic\Failure Probability | Failure Probability 1 | Failure Probability 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Kalman Filter-Based Fault Detection | 4.25 × 10−8 | 1.90 × 10−7 |

| Robust Observer-Based Fault Detection | 3.45 × 10−8 | 1.55 × 10−7 |

| One-Way Alarm Detection Mechanism | 1.85 × 10−8 | 1.85 × 10−7 |

| Simultaneous Alarm Detection Mechanism | 1.50 × 10−8 | 1.05 × 10−7 |

| Comparison Dimension | Traditional Hardware Redundancy | Single Algorithm FDI | Resolving Redundancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Redundancy mechanism | Multiple hardware parallel | Single algorithm software | Multi-algorithm parallel voting logic |

| SWaP requirements | High (Weight/power consumption/large size) | Very low | Low (increases computational load only) |

| Fault detection capabilities | High (depends on hardware diversity) | Limited by algorithm design | Heterogeneous complementarity reduces common cause failures |

| Reliability level | Very high | Lower | high |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, L.; Ma, C.; Yang, J. Study on Certification-Driven Fault Detection Threshold Optimization for eVTOL Dual-Motor-Driven Rotor. Aerospace 2025, 12, 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110973

Ma L, Ma C, Yang J. Study on Certification-Driven Fault Detection Threshold Optimization for eVTOL Dual-Motor-Driven Rotor. Aerospace. 2025; 12(11):973. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110973

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Liqun, Chenchen Ma, and Jianzhong Yang. 2025. "Study on Certification-Driven Fault Detection Threshold Optimization for eVTOL Dual-Motor-Driven Rotor" Aerospace 12, no. 11: 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110973

APA StyleMa, L., Ma, C., & Yang, J. (2025). Study on Certification-Driven Fault Detection Threshold Optimization for eVTOL Dual-Motor-Driven Rotor. Aerospace, 12(11), 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110973