1. Introduction

Manned–Unmanned Teaming (MUM-T) represents an integrated operational framework in which manned and unmanned platforms collaborate to accomplish mission objectives. Such systems enhance mission effectiveness, broaden operational capabilities, and simultaneously reduce human risk and personnel requirements, thereby establishing themselves as a pivotal component of future defense strategies [

1,

2]. With the increasing prominence of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in modern warfare, extensive research has been directed toward MUM-T concepts, particularly those involving the large-scale deployment of UAVs [

3,

4,

5,

6]. For example, the United States is advancing the Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) program, which employs UAVs to augment airpower and provide resilient responses to attrition warfare [

7]. Similarly, Europe, led by France, Germany, and Spain, is pursuing the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), a next-generation platform centered on manned–unmanned integration [

8].

To enable the effective coordination of multiple UAVs, multi-agent techniques such as path planning, task allocation, and formation flight are indispensable [

9]. Among these, formation flight is particularly critical, as it allows UAV groups to maintain predefined geometric configurations through cooperative control [

10,

11]. In the context of MUM-T operations, the leader–follower paradigm is commonly employed, wherein a manned platform serves as the leader to establish the overall formation, while follower UAVs maintain their relative positions and track the leader’s trajectory.

Formation flight systems can broadly be classified into centralized [

12,

13], decentralized [

14,

15], and distributed [

16,

17] architectures, depending on the approach to information exchange and decision-making. In a centralized scheme, a single control node aggregates data from all agents, processes it, and issues commands to the formation. This structure minimizes conflicts or inconsistencies in decision-making, as the central controller operates with complete situational awareness. However, as the number of agents increases, the computational and communication burden on the central node also grows, potentially causing delays and degrading control efficiency. Moreover, any failure of the central controller or disruption in communication can render the entire formation inoperable. This presents a fundamental limitation to reliability.

In contrast, decentralized schemes allow each agent to make independent decisions based on predefined rules and limited information exchange with neighboring agents. This approach scales more effectively with the number of agents and can adapt rapidly to environmental changes or unexpected events. Nevertheless, the autonomy of each node, combined with restricted situational awareness, makes it challenging to maintain consistent formation geometry.

Distributed schemes represent a balance between these two extremes, as agents share information with their local neighbors and make cooperative decisions through consensus mechanisms. This architecture enhances scalability and robustness, since the failure of a single agent does not compromise the entire formation, and neighboring agents can compensate for lost functionality. However, distributed approaches require continuous communication and significant computational resources to sustain coordination across the network.

In contemporary combat environments, mission complexity and precision requirements have intensified due to the proliferation of advanced air-defense systems, such as high-performance surface-to-air missiles, and the increasing prevalence of electronic jamming that disrupts communications [

18,

19]. To address these challenges, the ability to coordinate large numbers of UAVs in a resilient manner has become indispensable. In this context, distributed formation methods are particularly critical, as they combine scalability, reliability, and safety, positioning themselves as a key enabler for next-generation UAV operations.

Consensus-based formation control, a representative distributed strategy, enables each node to autonomously adjust its state through interactions with neighboring nodes, thereby allowing the entire formation to maintain a coherent configuration [

20,

21]. The communication and interaction topology among nodes can be modeled as a graph, and formation control methods built on this framework are collectively referred to as graph theory–based approaches. A central concept within this framework is rigidity theory, which determines whether the positions of follower nodes can be uniquely specified when the positions of a subset of nodes (e.g., leaders) are fixed. By leveraging rigidity theory, the formation can be guided to converge reliably toward the desired configuration.

Graph theory–based formation control can further be categorized according to the type of constraints applied. Common approaches include displacement-based [

22], distance-based [

23], and bearing-based [

24] methods, which rely on relative position, distance, or bearing information between nodes to establish and maintain the formation. Among graph theory–based approaches, bearing-based formation control has attracted significant attention due to its effectiveness in managing dynamic formations involving scaling and rotation. Building on this foundation, various studies have sought to address the practical challenges of formation tracking and obstacle avoidance. For instance, Van [

25] developed a sliding mode–based controller for robust formation tracking, while Ding [

26] proposed a nonlinear disturbance observer to address system uncertainties and unknown disturbances. Trinh [

27] introduced a leader–first follower graph structure, demonstrating that a unique formation can be maintained with only a single leader and the first follower, thereby overcoming the conventional requirement for multiple leaders.

Further advancements have focused on reducing dependence on global reference frames. Zhao [

28], Zhang [

29], and Sial [

30] proposed methods that rely solely on local coordinate frames, enabling greater autonomy and flexibility. Ramirez-Parada [

31] extended this concept by employing onboard visual sensors to derive relative directional information from neighboring UAVs, and showed that a leader UAV could dynamically adjust formation scale using visual data for obstacle avoidance. Likewise, Zhang [

32] developed a strategy for resizing formations to pass through constrained spaces, while Ding [

33] introduced mechanisms that combine scaling and rotation to improve obstacle-avoidance capability.

Despite these advancements, conventional leader–follower frameworks still present inherent limitations. In such structures, the leader is responsible for generating a collision-free path, while followers track its trajectory to maintain formation. However, this arrangement restricts the leader’s ability to account for the overall size and geometry of the group during avoidance maneuvers. As a result, even if the leader successfully avoids an obstacle, the safety of the followers cannot be assured. In bearing-based formations, follower positions are uniquely determined by two or more leaders, meaning that any positional adjustment requires deliberate modifications of the leaders themselves. Consequently, follower-level obstacle avoidance often necessitates artificial reconfiguration of the entire formation.

Existing approaches to obstacle avoidance—such as scaling or rotating the entire formation—are not only inefficient but also unsuitable for localized threats, since the entire group must be restructured even if only a single follower is at risk. Moreover, applying avoidance maneuvers independently to individual followers can propagate unintended movements to unaffected UAVs through inter-agent interactions, potentially destabilizing the formation. These limitations highlight the need for more flexible and localized obstacle-avoidance strategies that enable individual followers to adapt to threats while preserving overall formation integrity.

In this study, we propose a distributed formation flight control method for UAV swarms that relies on bearing information within a single-leader framework. Unlike conventional bearing-based approaches, which typically require multiple leaders, the proposed method establishes follower positions using only one leader, thereby simplifying the system architecture while maintaining scalability. Moreover, we introduce a novel collision-avoidance strategy that allows follower UAVs to maneuver efficiently around obstacles while preserving the integrity of the formation. We demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework through simulations of representative formation patterns, including V-shaped and hexagonal configurations. The results confirm that the system enables stable flight in complex, obstacle-rich environments while maintaining the designated formation behind a moving leader.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the fundamental concepts of bearing-based formation flight grounded in graph theory.

Section 3 introduces a new bearing-based formation framework developed to overcome the limitations of conventional methods.

Section 4 details the controller design for formation tracking and obstacle avoidance.

Section 5 and

Section 6 present the simulation results that validate the proposed method and provide a discussion of future research directions.

2. Theoretical Background

The connectivity of

n agents in

can be represented using graph theory. Let the undirected graph be denoted by

, where

is the set of vertices (agents), and

is the set of edges representing the connectivity among agents. If agent

i receives information from agent

j, then

, and agent

j is referred to as a neighbor of agent

i. Accordingly, the neighbor set of agent

i is defined as

Let the number of leaders in the formation be

and the number of followers be

, such that

and

. The leader set is defined as

and the follower set as

. Thus, the complete set of agents is given by

. The position and velocity of each agent

are denoted by

. Accordingly, the position and velocity vectors of the leaders and followers, denoted by

and

, respectively, are defined as follows:

The bearing vector obtained by agent

i from its neighbor

is defined as in Equation (

1):

where

is a unit vector representing the relative direction from agent

i to agent

j, and it satisfies the antisymmetry property

. Using this bearing vector

, the corresponding orthogonal projection matrix

is defined in Equation (

2):

This projection matrix projects any vector onto the subspace orthogonal to

. It is positive semidefinite and satisfies

The target positions of the agents are denoted by

, and the desired bearing vectors by

. Accordingly, the target formation

must satisfy the constraints given in Equations (

3) and (

4):

Equation (

3) defines the bearing constraint of the target formation, ensuring that each agent’s target position

satisfies the prescribed bearing vector

with respect to its neighbors. Equation (

4) imposes the leader position constraint, requiring that the current leader positions coincide with their designated target positions. Together, these constraints guarantee that the target formation is realized with the leaders serving as reference points.

Given the desired bearing vectors

, the bearing Laplacian matrix

is defined in Equation (

5):

The bearing Laplacian matrix incorporates both connectivity and bearing information of the target formation, thus constraining the formation based on relative bearing vectors between agents. This matrix provides a structured representation of the relationships between leaders and followers. As shown in Equation (

6), the bearing Laplacian for a leader–follower formation can be partitioned into block matrix form:

where

denotes the block associated with leaders,

represents leader–follower interactions, and

corresponds to follower–follower interactions.

Zhao and Zelazo [

24] derived the following lemma using the bearing Laplacian matrix.

Lemma 1. Any formation that satisfies the bearing constraints satisfies Equation (7)

. If

is invertible, the above relation yields Equation (

8):

This expression indicates that the follower positions

can be uniquely determined from the leader positions

, given the bearing constraints

. In other words, once the leaders’ positions are fixed, the target formation is uniquely defined, thereby ensuring

bearing-localizability of the formation.

To uniquely determine the target formation , the follower–follower subgraph must be nonsingular, and the following conditions are assumed to guarantee this property.

Assumption 1. The target formation is infinitesimally bearing rigid and has at least two leaders.

The first condition in Assumption 1, infinitesimal bearing rigidity (IBR), provides a sufficient condition for ensuring the bearing-localizability of the target formation. The second condition, requiring the existence of at least two leaders, constitutes a necessary condition. In particular, the validity of IBR can be determined from the rank of the bearing Laplacian matrix associated with the network, which must satisfy the following necessary and sufficient condition [

34]:

where

d is the space dimension and

n is the number of agents.

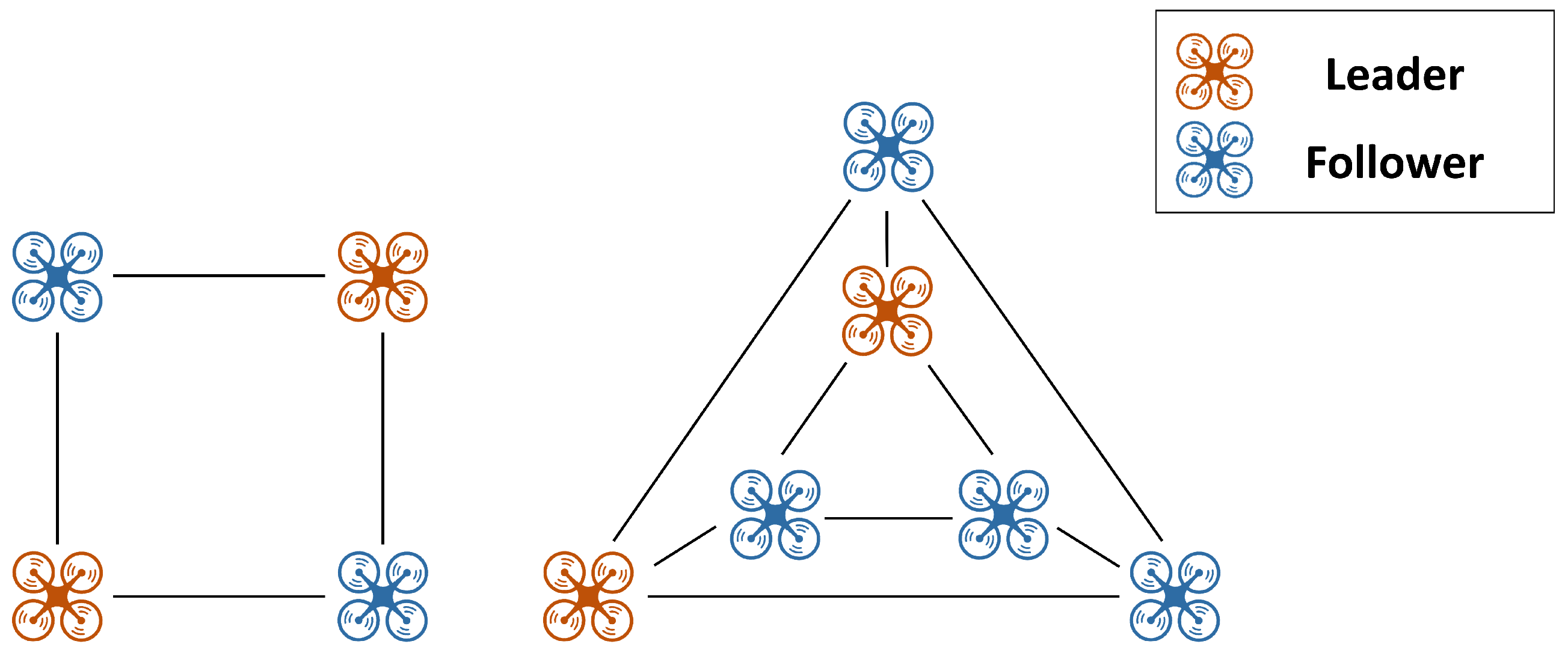

However, IBR is only a sufficient condition for bearing-localizability. As illustrated in

Figure 1, there may exist networks in which the target formation is bearing-localizable even though IBR is not satisfied. When the number of agents is small, the bearing-localizability of a network can often be evaluated intuitively from its structure or constraints. However, as the number of agents increases, it becomes progressively more challenging to determine bearing-localizability directly. Therefore, for large-scale networks, only formations that satisfy IBR may be considered to guarantee bearing-localizability. Nevertheless, as the system size grows, constructing an IBR network that fulfills the necessary and sufficient condition in Equation (

9) requires increasingly complex and precise connections, making network design inherently more difficult.

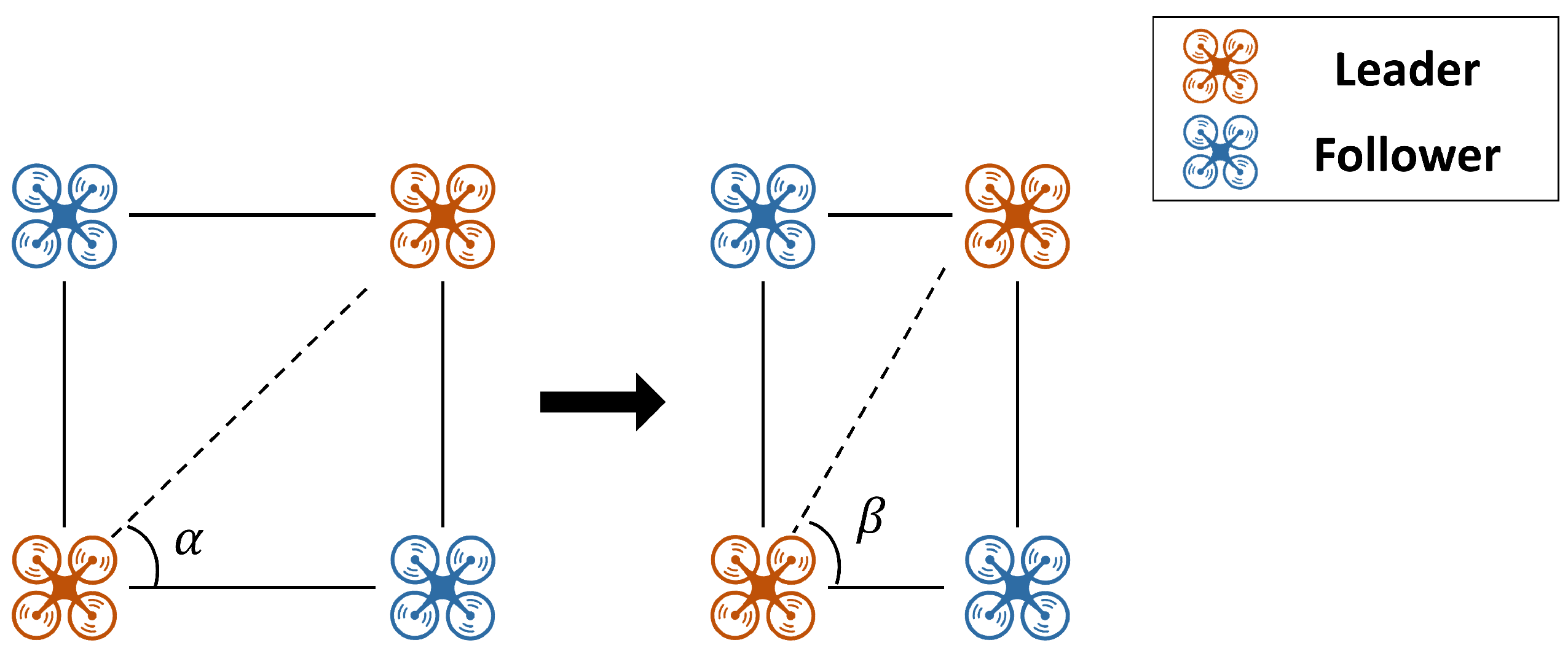

In a leader–follower formation system, two leaders must be precisely positioned at designated locations to realize the target formation. If the relative position between the two leaders deviates from that of the desired target formation, as illustrated in

Figure 2, the followers adapt to this change and converge to an unintended configuration. Since the overall formation is determined by the relative positions of the leaders, precise control of the leaders is essential to maintain the desired shape. However, in MUM-T systems with two manned leaders, the independent decisions and maneuvers of each leader can inherently destabilize their relative positioning. Consequently, this imposes a significant burden on formation maintenance.

3. Bearing-Based Target Formation Configuration

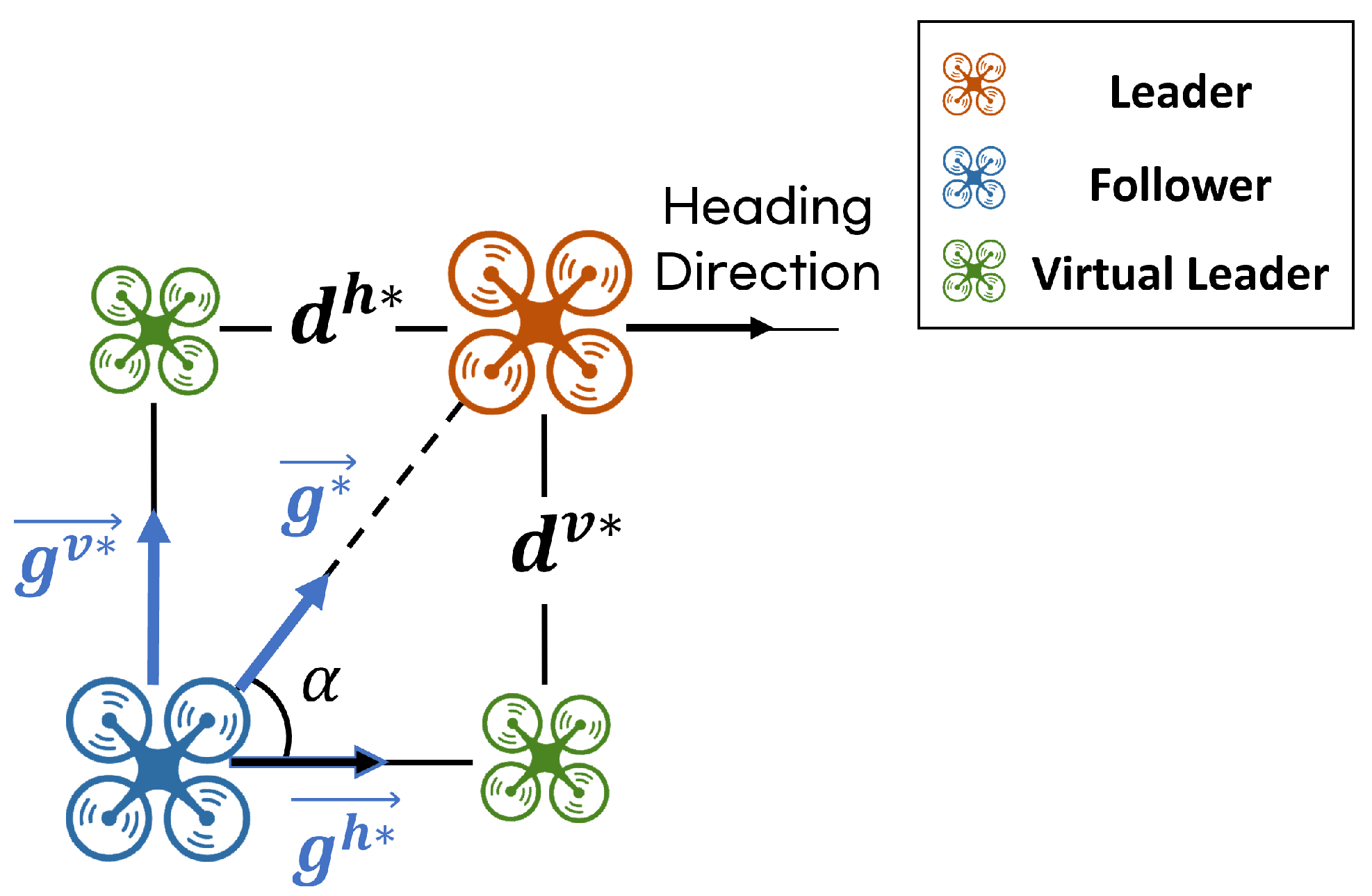

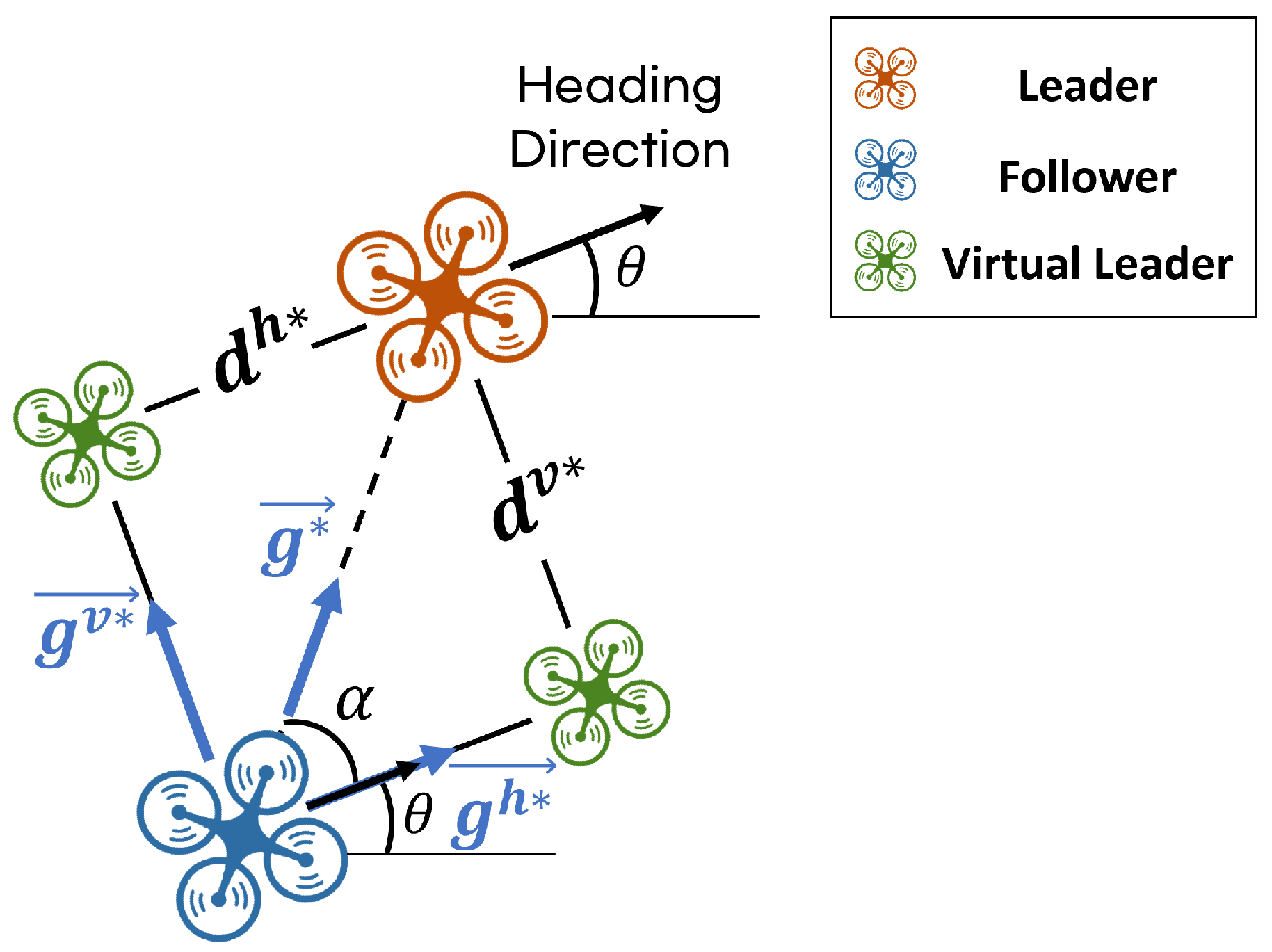

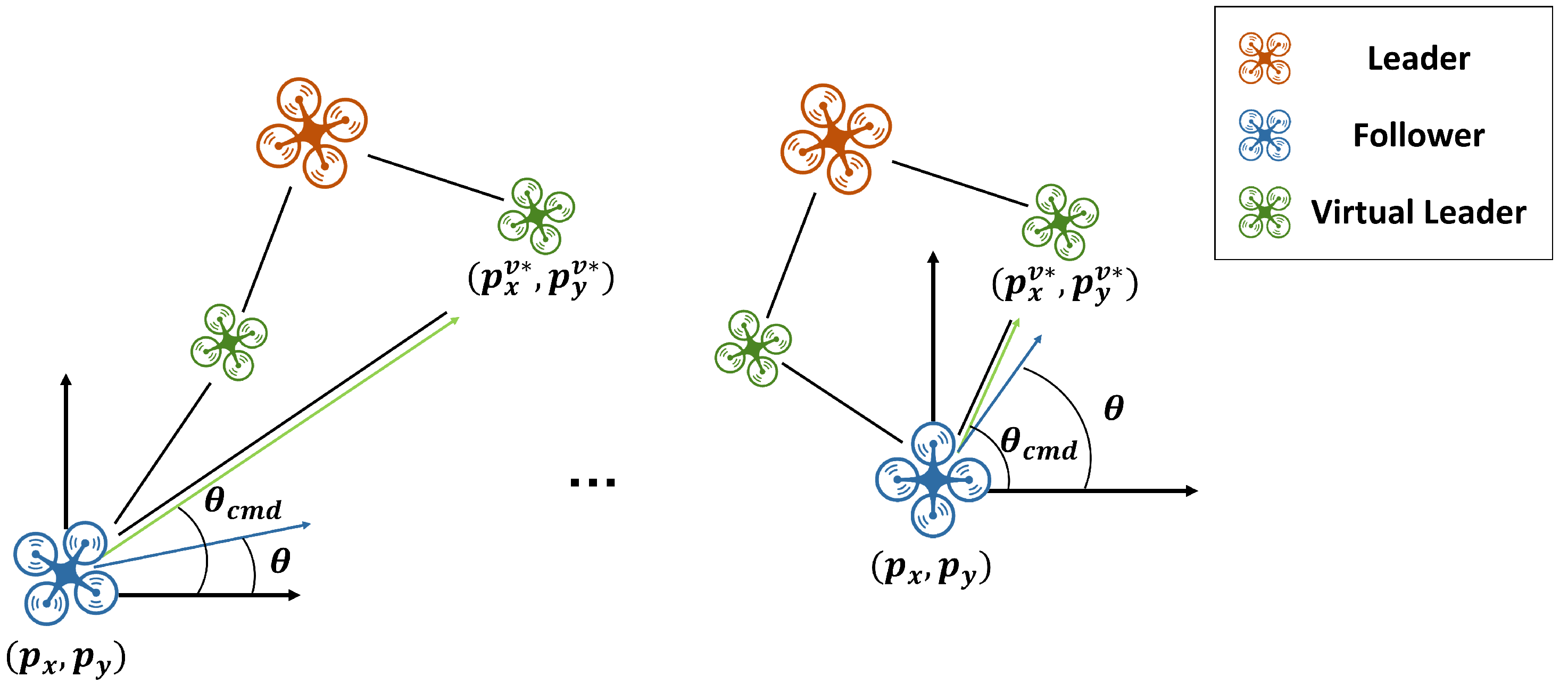

To overcome the limitations of conventional bearing-based formation systems, this study introduces a novel framework that employs virtual leaders, as illustrated in

Figure 3. First, two virtual leaders are introduced: one located at a distance

along the longitudinal axis (aligned with the leader’s heading angle) and the other at a distance

along the lateral axis (perpendicular to the heading angle). The position of each follower is then defined to satisfy the bearing constraints with respect to these virtual leaders, with target bearings

and

. In this formulation, the longitudinal virtual leader determines the forward position of the followers, while the lateral virtual leader governs their lateral position.

In conventional bearing-based formation control, the inter-agent bearings are predefined and fixed, thereby limiting flexibility in adjusting the formation. In contrast, in the proposed method, followers are not required to directly satisfy the bearing constraint with respect to the actual leader. Instead, they are guided to satisfy according to the ratio of to . As a result, even if and are predefined bearing constraints, the bearing condition relative to the actual leader can be flexibly adjusted during flight by regulating this ratio. Since and are orthogonal unit vectors aligned with the longitudinal and lateral axes, respectively, modifying the position of one virtual leader does not affect the bearing constraints associated with the other. For instance, even if the longitudinal virtual leader shifts—changing the forward displacement of the follower—the lateral virtual leader still preserves its bearing relationship with the follower. This property allows the formation to be flexibly adjusted while maintaining its structural integrity.

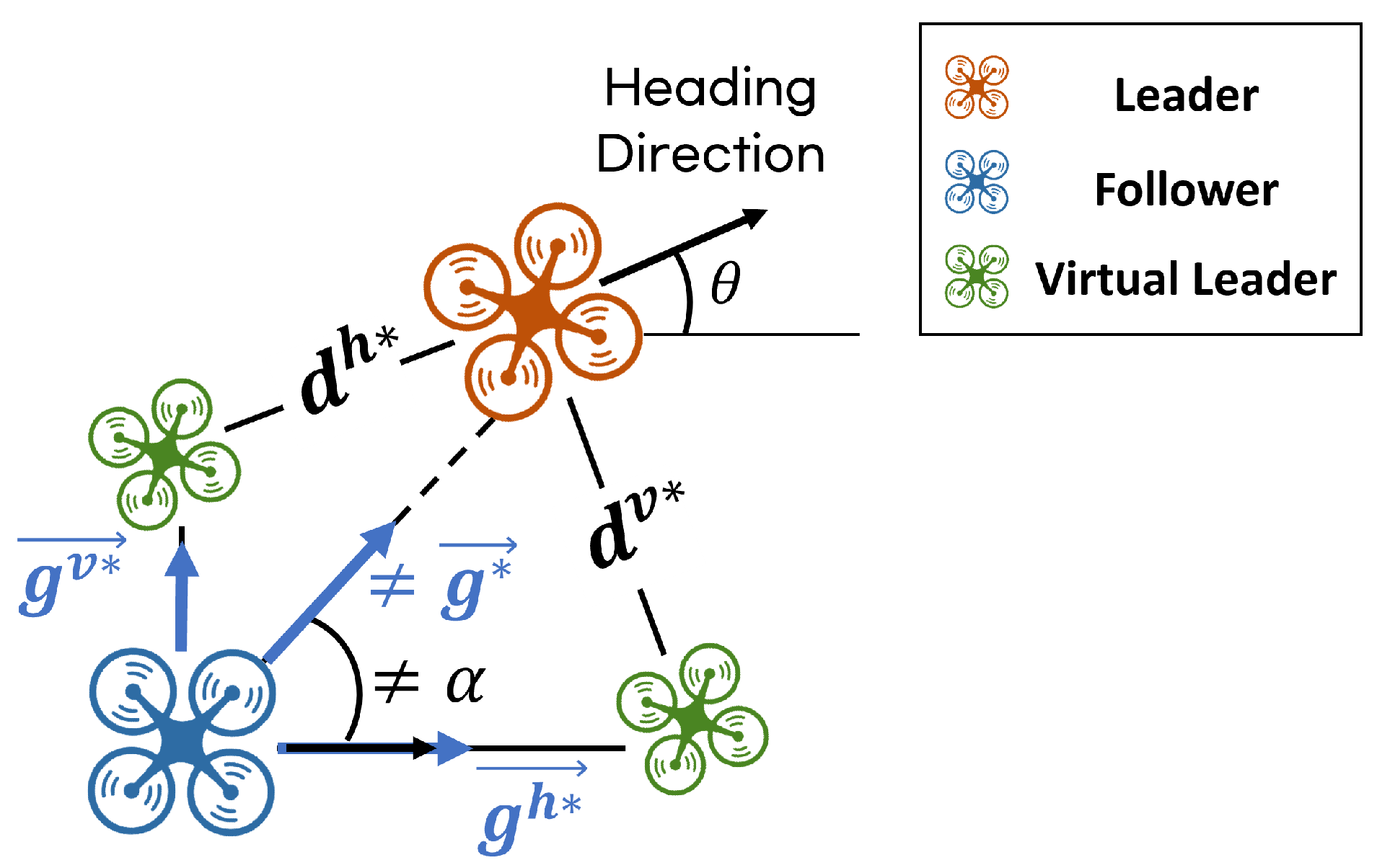

When the leader has a heading angle

, the follower’s position can be computed relative to the rotated virtual leaders, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The follower satisfies the bearing constraints with respect to the virtual leaders,

and

. However, it is not aligned with the actual leader’s heading direction and therefore does not conform to the relative bearing constraint

between the follower and the leader. This discrepancy arises because the follower does not directly account for the leader’s attitude.

To address this issue, a rotation matrix incorporating the leader’s heading angle is applied to Equation (

8), yielding Equation (

10). Through this process, the follower becomes aligned with the leader’s direction while simultaneously satisfying the desired bearing constraints, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

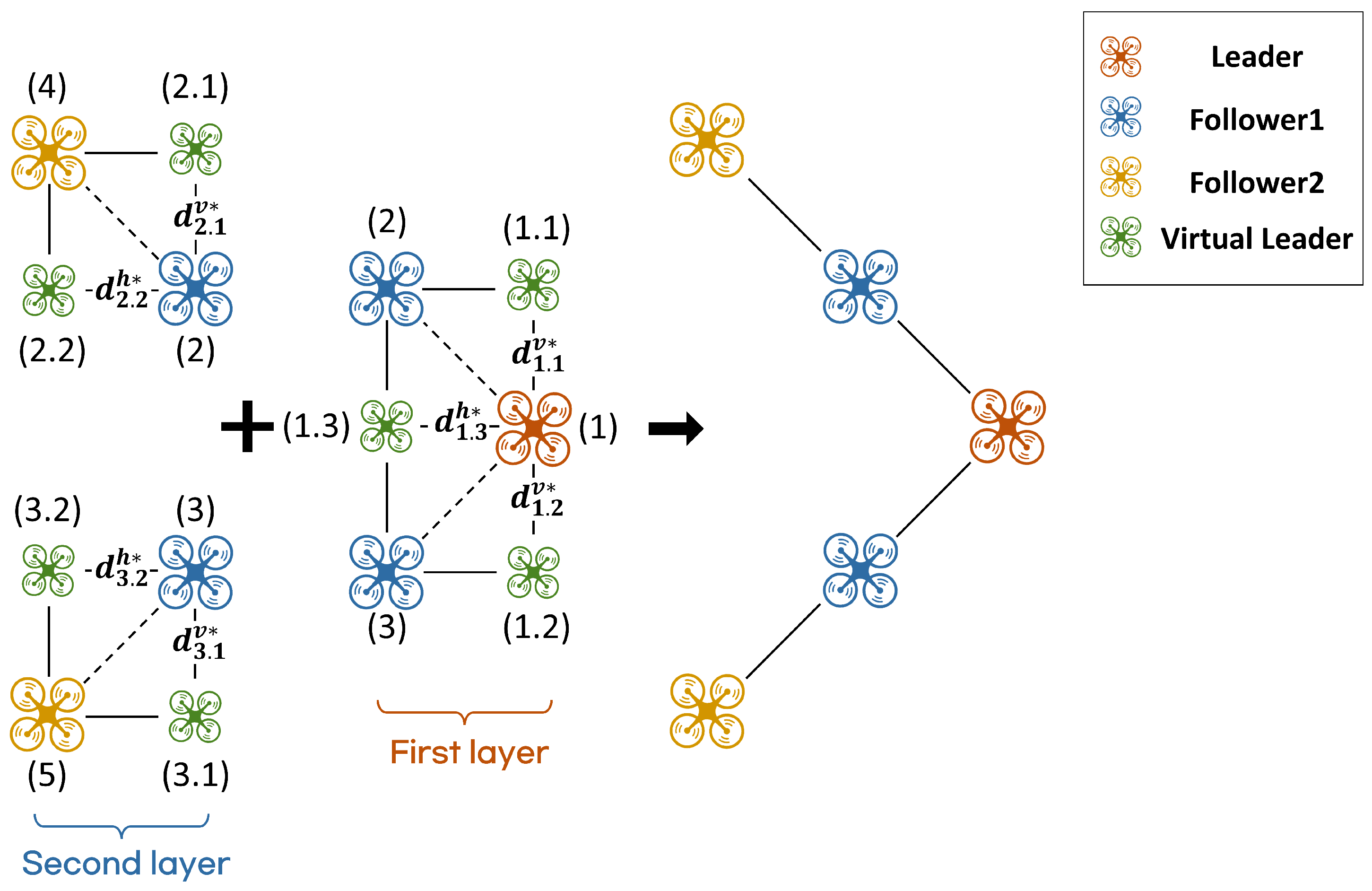

The proposed virtual-leader-based formation system serves as a fundamental module for constructing larger formations. By hierarchically combining these modules, a wide range of formation patterns can be generated. Each module adopts a leader–follower structure, in which lower-layer followers track upper-layer followers in a hierarchical manner. This architecture not only enhances the scalability of the multi-agent system but also allows the entire formation to be controlled by a single leader. In this study, the proposed framework is applied to realize V-shaped and hexagonal formations.

To configure the V-shaped formation, all UAVs—including the virtual leaders—are indexed, and the longitudinal and lateral reference distances assigned to each follower are summarized in

Table 1. Here,

and

denote the longitudinal and lateral reference distances, respectively, with subscripts indicating the leader index and the corresponding virtual leader index. For example,

represents the lateral reference distance between UAV 1 (leader) and UAV 1.2 (virtual leader), while

represents the longitudinal reference distance between UAV 1 (leader) and UAV 1.3 (virtual leader).

Figure 6 illustrates a formation in which the leader is positioned at the front, while the followers form a V-shaped structure to track it. The formation is organized into two layers: in the first layer, UAVs 2 and 3 follow UAV 1 (the leader), and in the second layer, UAVs 2 and 3 act as leaders, with UAVs 4 and 5 assigned to follow them.

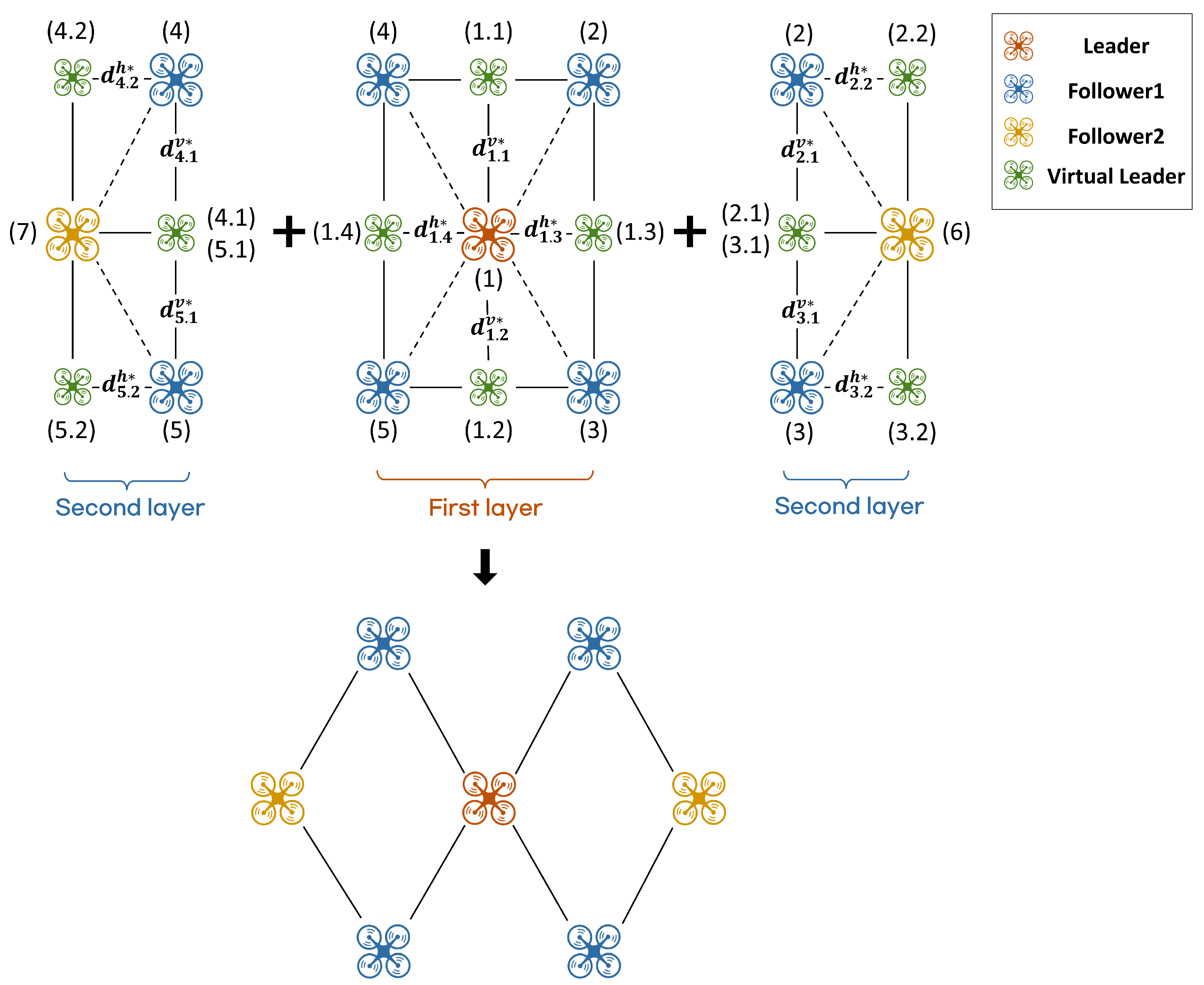

Figure 7 illustrates a hexagonal formation in which the followers are arranged around the leader in two layers, with the corresponding formation parameters summarized in

Table 2. In the first layer, four follower UAVs 2–5 track UAV 1 (the leader). In the second layer, follower UAVs 6 and 7 are assigned to follow UAVs 2 and 3, and UAVs 4 and 5, respectively, with the first-layer followers serving as leaders.

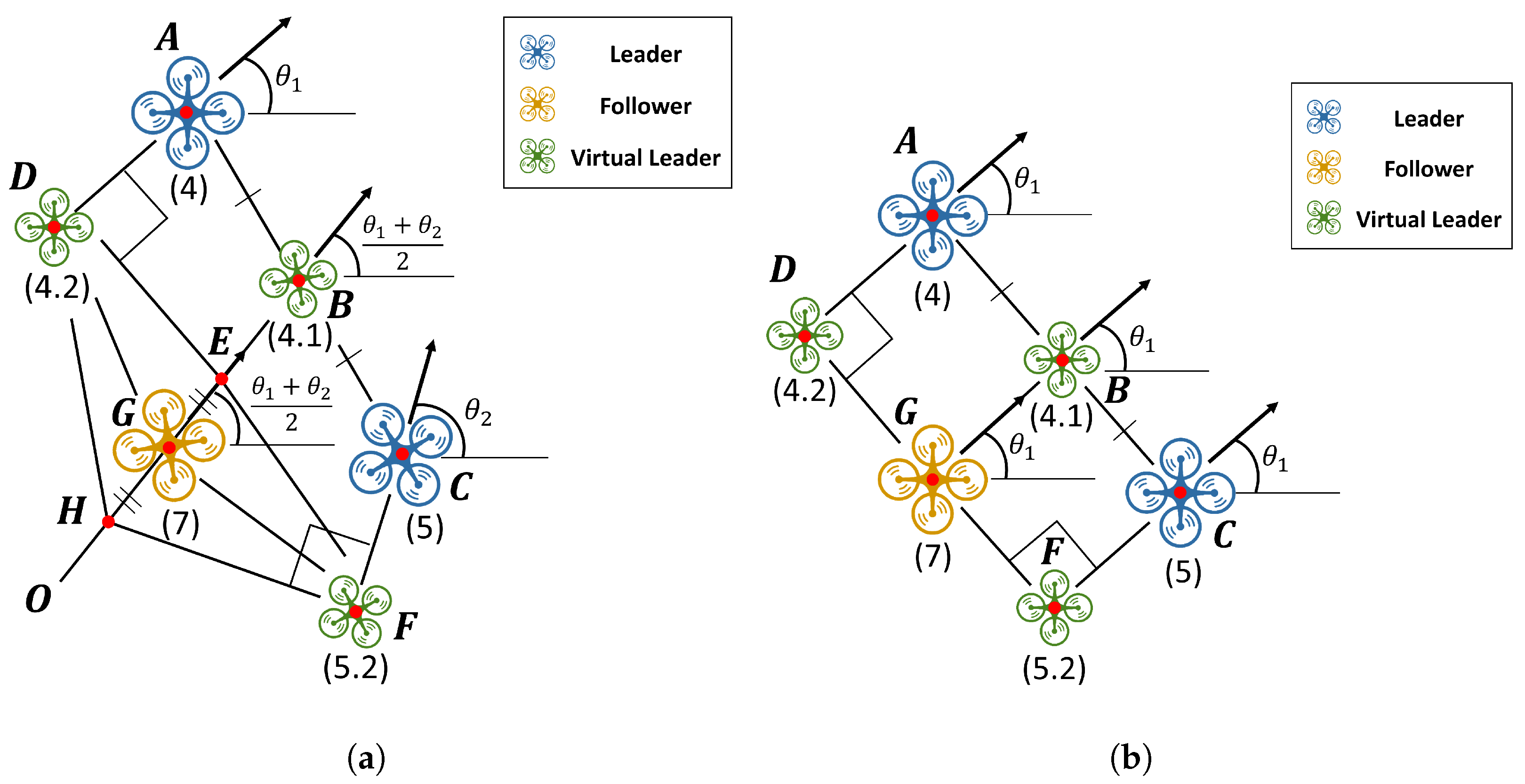

When a single follower is required to track two leaders, its position is determined using the method shown in

Figure 8a. The positions of leader UAVs 4 and 5 are denoted as points

A and

C, respectively. UAV 4.1 (a virtual leader), which defines the follower’s lateral position, is determined by the relative location of follower UAV 7 between the two leaders in the target formation. Since follower UAV 7 is positioned at the midpoint of UAVs 4 and 5 in

Figure 7, UAV 4.1 is placed at point

B, the midpoint of

. The heading angle referenced by follower UAV 7 is also defined with respect to this virtual leader and is set to the average of the two leaders’ headings, consistent with the position definition. The longitudinal position of follower UAV 7 is determined using UAVs 4.2 and 5.2, which are aligned with the heading directions of leader UAVs 4 and 5. From the positions of UAVs 4.2 and 5.2, lines perpendicular to their respective heading directions (

and

) are drawn. Let

H and

E denote the intersections of these lines with

, which represents the heading direction of UAV 4.1. The midpoint of

is then taken as the longitudinal position of follower UAV 7. If leader UAVs 4 and 5 converge exactly to the target formation defined in the previous layer—thus sharing the same heading angle—points

E and

H coincide, and follower UAV 7 completes the hexagonal structure shown in

Figure 8b.

By utilizing a formation system based on one or two leaders, the proposed approach can be extended to various formation shapes beyond the previously presented V-shaped and hexagonal configurations. Furthermore, if the longitudinal and lateral positions of followers can be geometrically defined with respect to multiple leaders, formations involving a larger number of leaders can also be constructed. This formation approach provides scalability and flexibility, enabling the construction of more complex and diverse swarm structures.

4. Mode-Based Control Strategy

The formation motion is governed by the leader’s position

, which serves as the reference, together with the bearing constraints

that define the target formation

. Bearing-based formation control regulates the follower positions

such that they converge to the desired positions

using relative bearing measurements with respect to neighboring nodes. In this study, each UAV is assumed to follow the holonomic dynamic model given in Equation (

11), which serves as the basis for tracking and maintaining the target formation:

where

,

and

denote the longitudinal and lateral velocities in the body-fixed frame,

is the UAV’s heading angle, and

is the angular velocity.

For practical deployment of a formation system, it is essential for followers to not only maintain formation but also actively avoid obstacles in environments. To achieve this, a control architecture was developed that enables each follower to switch between three modes of operation based on its conditions. In the first mode, Formation Tracking Mode, followers initially at arbitrary positions apply formation control to achieve the desired formation by tracking the leader. In the second mode, Collision Avoidance Mode, is activated when an obstacle is detected, temporarily modifying the formation to prevent potential collisions. Finally, the Formation Maintenance Mode maintains the stability of the formation by minimizing unnecessary movements of the followers, which may distort the overall structure.

Each controller is designed independently, with the

Formation Tracking Mode described in

Section 4.1, the

Collision Avoidance Mode presented in

Section 4.2, and the

Formation Maintenance Mode detailed in

Section 4.3. The criteria and procedures for mode switching are also detailed in

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.3.

4.1. Formation Tracking Mode

Within the hierarchical leader–follower structure, the position, velocity, and heading of each leader vary over time, and it is assumed that each UAV has access to the state information (position and heading) of its designated leader. Before designing the controller that governs the longitudinal and lateral velocities of the follower, the input saturation is taken into account. These constraints are formulated in Equation (

12):

where

and

,

,

.

Considering the saturation of the control inputs, the controller is designed following the method proposed by Li [

35] and is formulated in Equation (

13):

where

and

denote the unit vectors aligned with and orthogonal to the heading direction of agent

i, respectively.

and

represent the rotation matrices corresponding to the heading angles of the leader and each follower, respectively. Indices

j and

k indicate the virtual leaders that specify the follower’s longitudinal and lateral positions. The parameters

and

represent the proportional and integral gains for position control, while

denotes the proportional gain for heading control. All gains are positive, satisfying

.

The position of the follower in the local frame, taking into account the saturation of velocities, is expressed in Equation (

14).

To verify that the proposed controller guarantees convergence to the desired target position, the Lyapunov function defined in Equation (

15) is considered:

By defining

and

, the time derivative of the Lyapunov function can be expressed as in Equation (

16):

where

, and therefore

is always positive definite.

The Lyapunov function

V is nonnegative, and since its time derivative satisfies

, the system is stable. According to LaSalle’s invariance principle [

36], the system trajectories converge to the largest invariant set

satisfying

, which is characterized by

and

are independent of each other; therefore, they satisfy

and

. Under Lemma 1 and Assumption 1, this ensures that the followers converge to the desired target positions.

The angular velocity controller for each follower is designed to align its heading angle with that of the leader, as illustrated in

Figure 9.

where

and

represent the positions of the virtual leader, which determines the lateral reference, and the follower, respectively.

The follower can reach the target position through forward and lateral movements, and as it converges to the desired position, its heading angle naturally aligns with that of the leader.

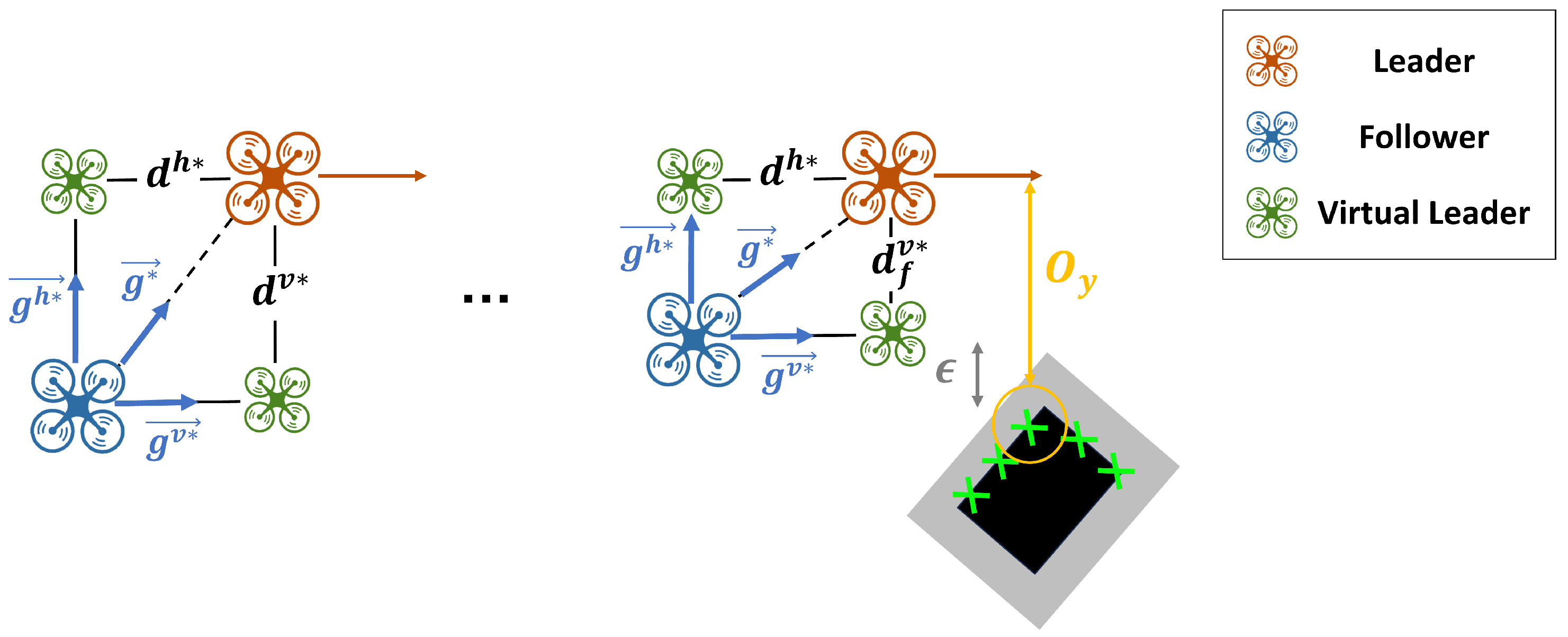

4.2. Collision Avoidance Mode

As shown in

Section 3, the bearing constraints

between a follower and its leader can be regulated by adjusting the relative distances

and

between the follower and the virtual leaders. In general, leaders generate trajectories to avoid obstacles; however, depending on the formation size and geometry, collisions between followers and obstacles may still occur. To address this issue, followers are designed to switch from the

Formation Tracking Mode to the

Collision Avoidance Mode when the collision condition specified in Equation (

18) is satisfied:

where

denotes the position of the nearest obstacle along the

y-axis in the body-fixed coordinate frame of the leader being tracked by the follower, and

denotes the minimum safety distance required to ensure collision avoidance.

During flight, each follower detects obstacles and computes

using the position and heading information received from its leader. If the lateral distance

in the target formation exceeds

, the follower identifies a potential collision and switches to the

Collision Avoidance Mode. In this mode, as illustrated in

Figure 10, the lateral distance

between the leader and the follower is temporarily adjusted to

, enabling the follower to avoid the obstacle.

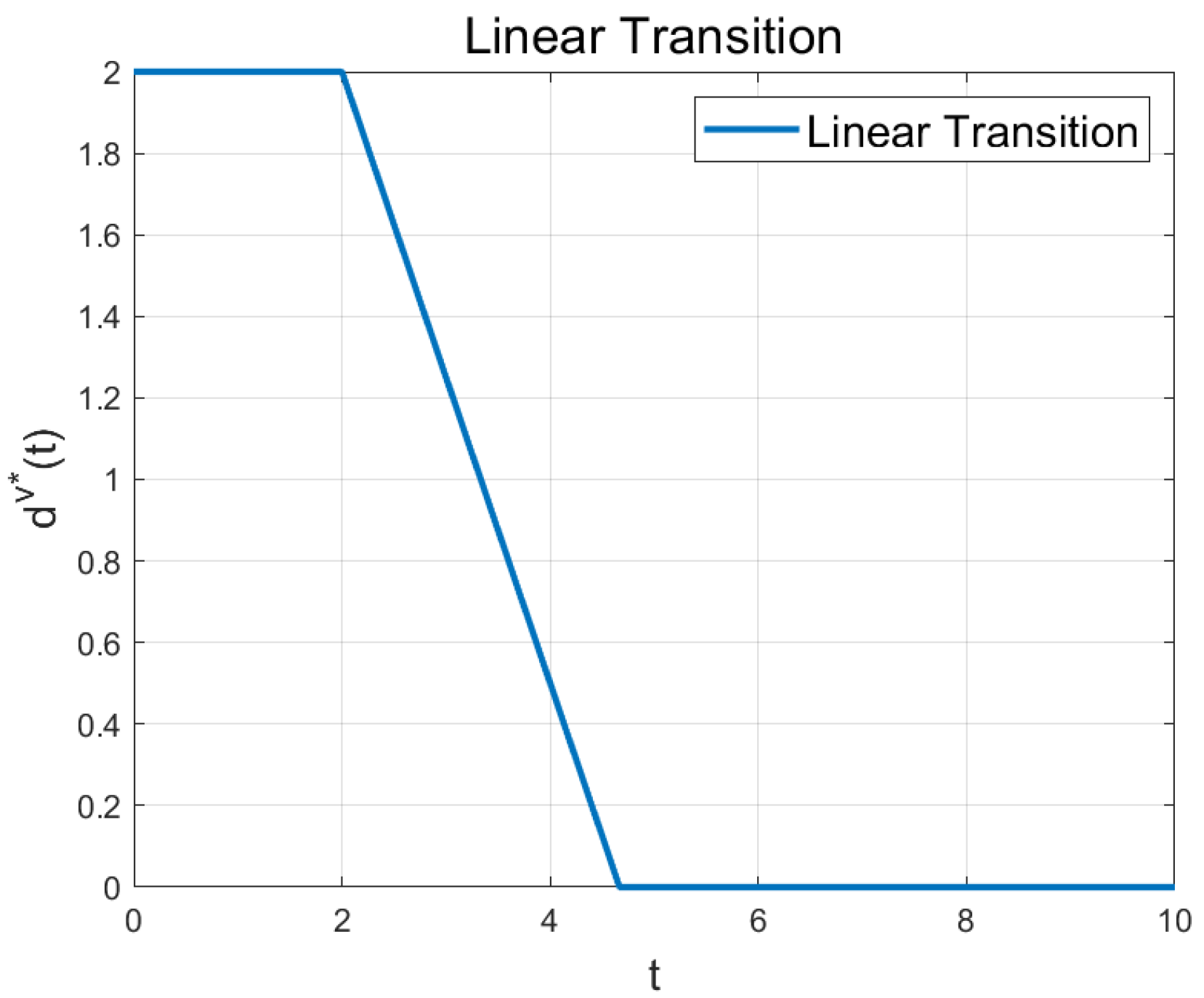

Equation (

19) imposes a constraint preventing the follower from crossing to the opposite side of the leader. In this case,

is not instantaneously replaced by

; instead, as illustrated in

Figure 11, it is designed to vary continuously over time using a linear transition function.

where

and

denote the initial and final lateral distances, respectively,

represents the initial time when the transition begins, and

t is the current time. The parameter

denotes the time required for the distance to change from

to

, and is given by

When switching from the Formation Tracking Mode to the Collision Avoidance Mode, corresponds to the lateral distance in the original target formation, . is the modified at the moment of mode switching, and denotes the time at which the transition begins. If the adjusted distance changes during obstacle avoidance, the initial value of the transition function is updated to the current lateral distance , and is reset to the corresponding update time. Once obstacle avoidance is completed, the recovery process is performed in the reverse direction, where is set to and is restored to the original .

In the proposed hierarchical leader–follower system, variations in the leader’s heading angle directly affect the target positions of the follower UAVs, often leading to abrupt position changes. Once the formation stabilizes, fluctuations in a follower’s angular velocity can significantly affect the motion of the trailing UAVs. Therefore, in the Collision Avoidance Mode, each follower is designed to use only lateral velocity control to satisfy the bearing constraint with respect to the varying virtual leader, where .

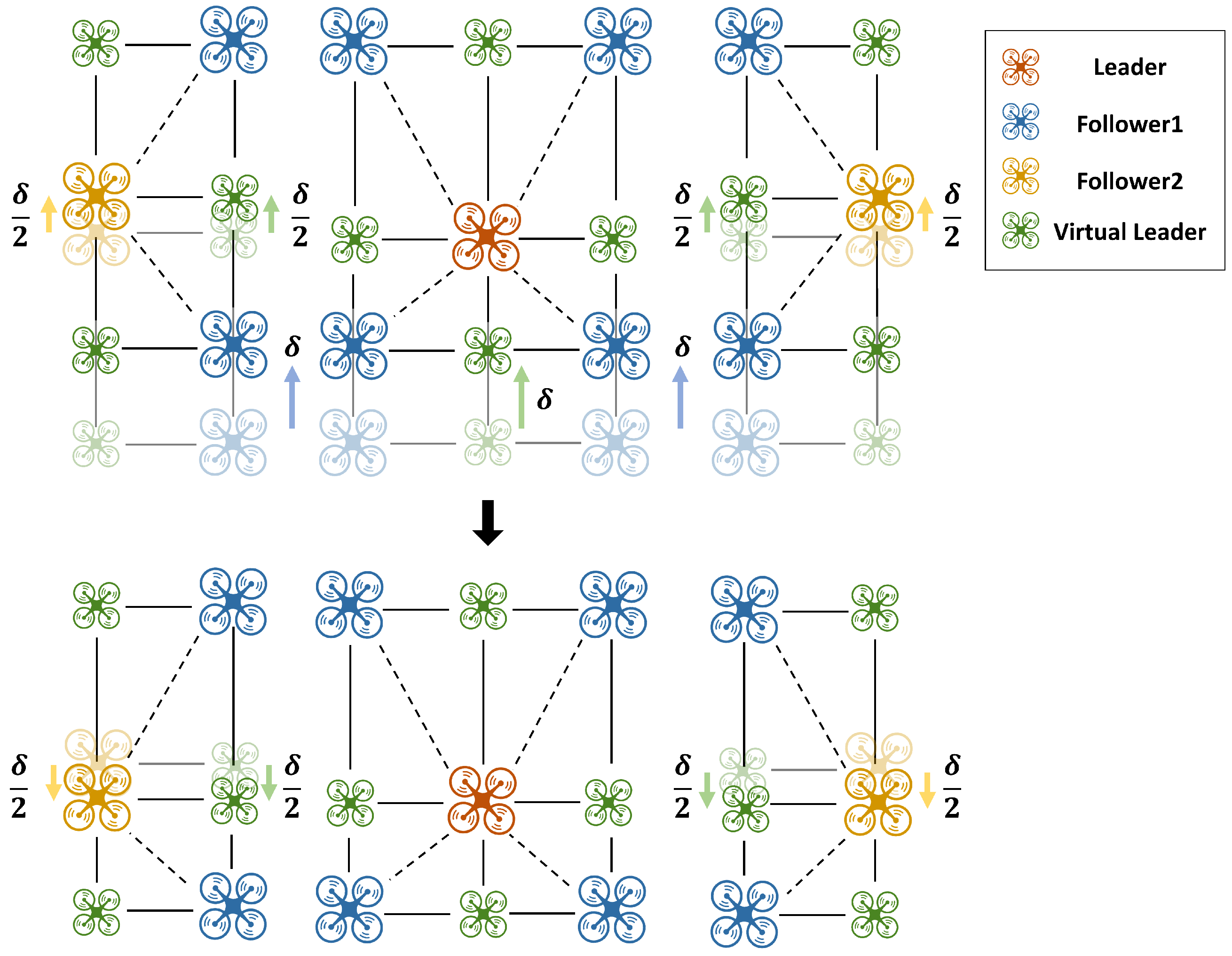

4.3. Formation Maintenance Mode

If the leader enters the Collision Avoidance Mode while the follower remains in the Formation Tracking Mode, the follower unnecessarily changes its position by tracking the leader’s varying lateral displacement, despite the absence of any collision risk. These unnecessary movements propagate to other agents, thereby undermining overall formation consistency and reducing the system’s operational efficiency.

To address this issue, we propose a method in which the follower receives the leader’s lateral displacement

and readjusts its virtual leader position in real time, thereby minimizing unnecessary movements. This approach is illustrated using the hexagonal formation structure shown in

Figure 12. When the two bottom followers ascend by

for obstacle avoidance, the followers in the next layer ascend by

. In this process, lower-level followers receive the leader’s lateral displacement

from their upper-level leaders in real time and use it to readjust the position of their virtual leader, which determines their own lateral position. This mechanism not only preserves the overall formation by modifying the distance condition in coordination with the upper-level followers performing collision avoidance, but also reduces unnecessary movements among the followers.

5. Simulation Results

To validate the proposed hierarchical leader–follower bearing-based formation flight system, MATLAB R2024b simulations were conducted for the previously designed V-shaped and hexagonal formations. The simulation scenarios are summarized in

Table 3.

In the first scenario, the leader flies in a straight line at a constant velocity, whereas in the second scenario, the leader follows a circular trajectory. The initial positions and heading angles of both the leader and the followers were randomly assigned, and all followers employed the same controller. The simulation parameters, including the controller gain values, are summarized in

Table 4.

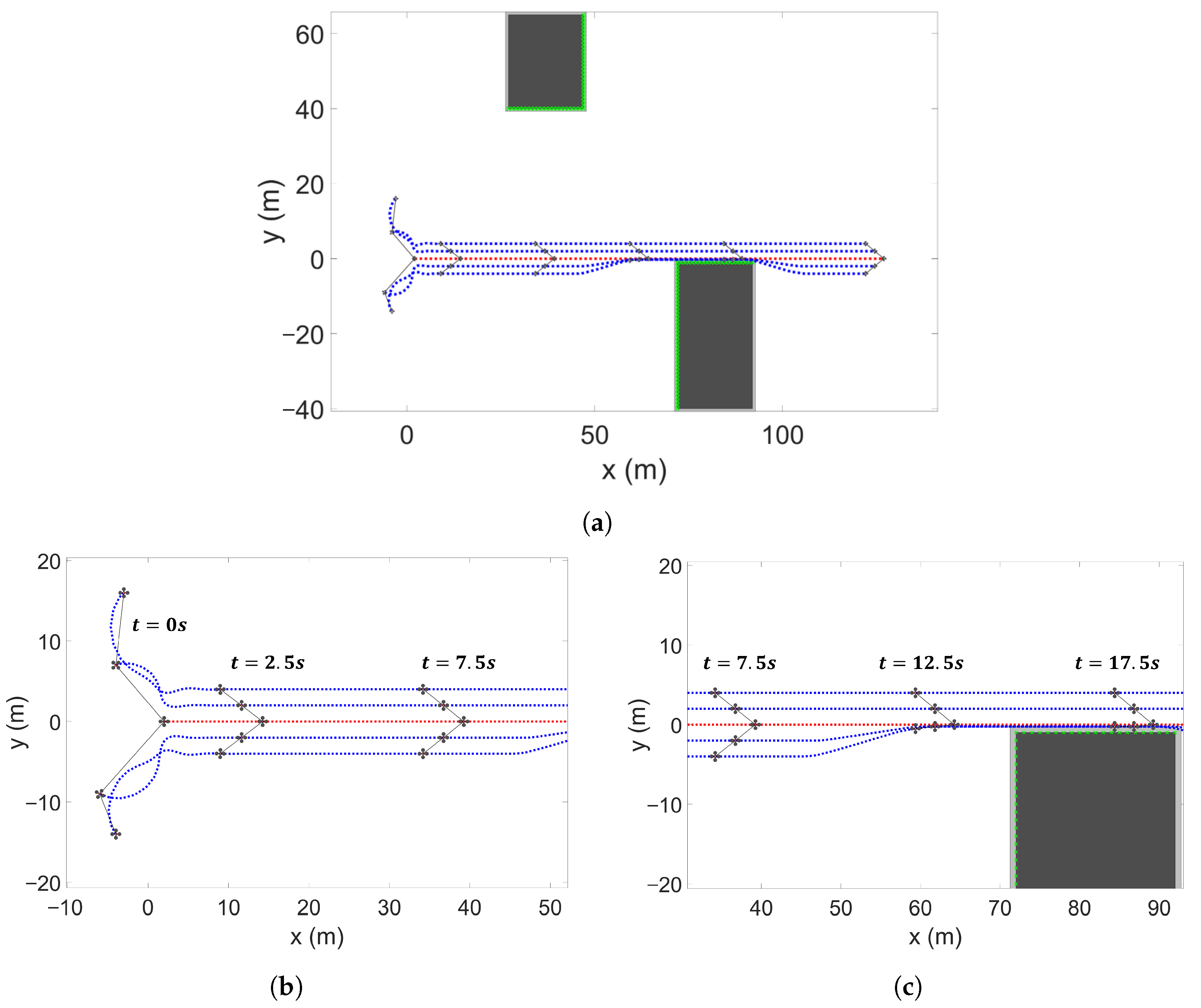

The simulation results of the V-shaped formation under straight-line flight are shown in

Figure 13.

Figure 13a shows the overall simulation results, while

Figure 13b–d provide a detailed chronological breakdown. As illustrated in

Figure 13b, the followers converge to a V-shaped formation within approximately 2.5 s. Subsequently, in

Figure 13d, UAVs 3 and 5 are predicted to collide with an obstacle at 10 s and therefore switch from the

Formation Tracking Mode to the

Collision Avoidance Mode.

Follower UAV 3 avoids the obstacle nearest to the

y-axis relative to its leader (UAV 1) by setting

. According to the linear transition function, the virtual leader’s lateral position is adjusted as

, enabling the follower to successfully avoid the obstacle. Similarly, UAV 5 switches to the

Collision Avoidance Mode with

and adjusts its lateral distance

accordingly. In such cases, when both the leader UAV and its follower are in the

Collision Avoidance Mode, the follower sets

to remain aligned with the bearing line of its leader. To avoid the obstacles, UAVs 3 and 5 maintain

and

for

s, after which the formation recovers to its original configuration (see

Figure 13d).

Figure 13e shows the errors between the desired and actual positions of each follower UAV over time. The results indicate that UAVs 3 and 5 temporarily deviate from the nominal formation during obstacle avoidance, with maximum position errors of

and

, respectively. Afterward, the UAVs reconverge to the desired formation, confirming the stability and robustness of the proposed method.

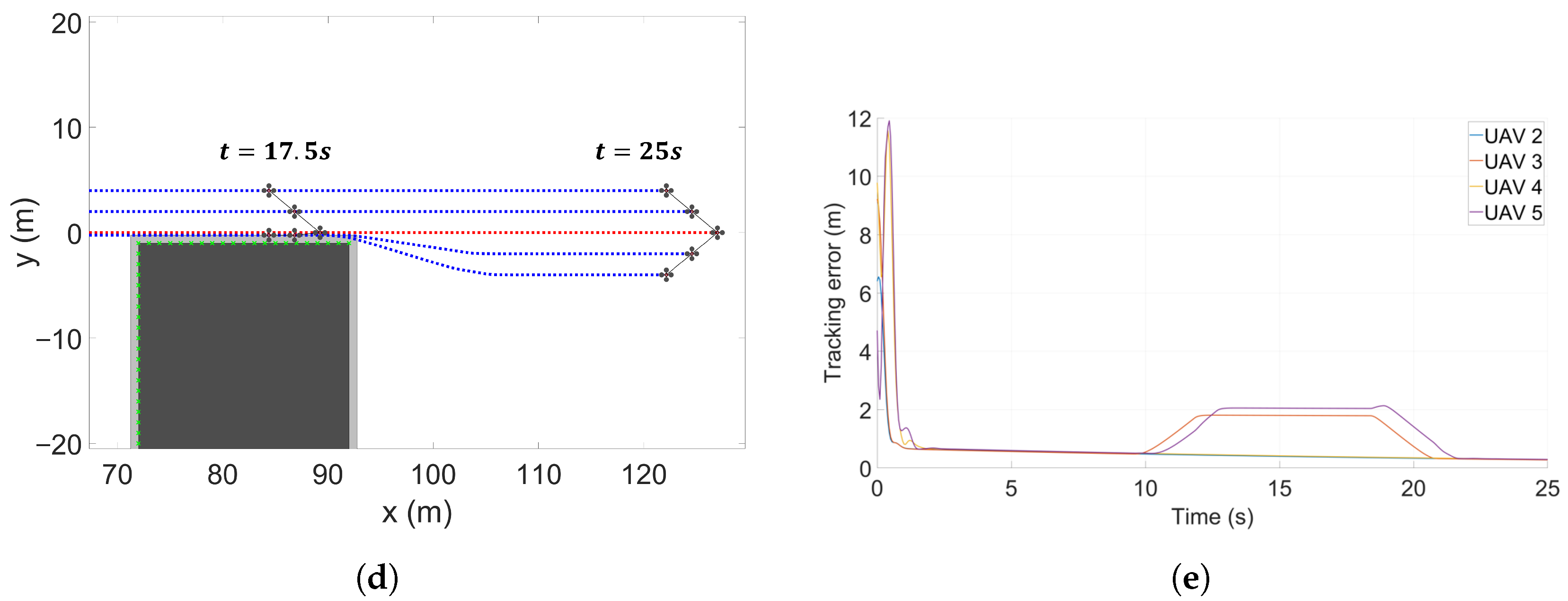

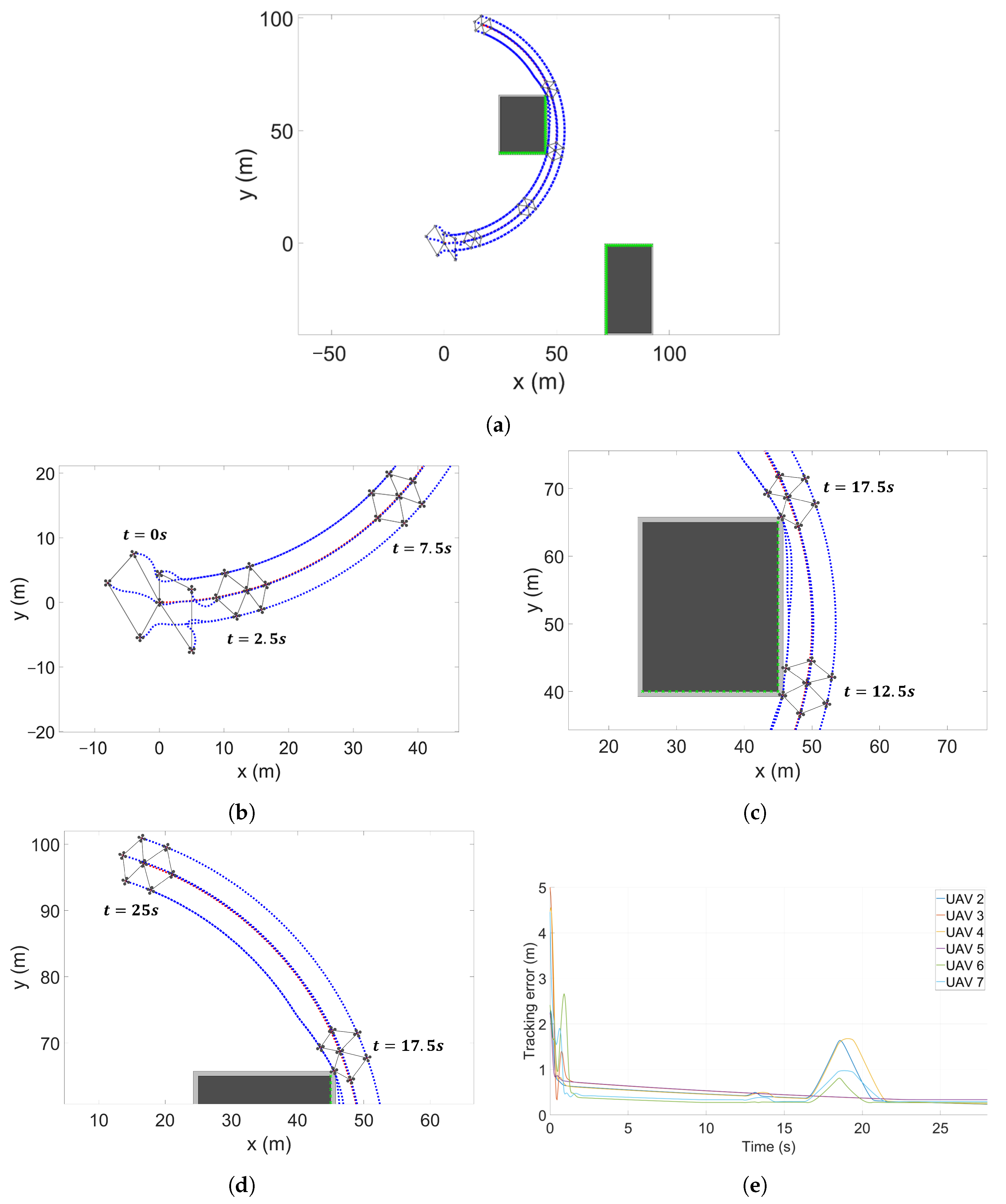

The results of the circular flight simulation for the V-shaped formation are shown in

Figure 14. The followers converge to the V-shaped formation within approximately

s, even under circular motion. Subsequently, in

Figure 14c, UAV 4 is predicted to collide with an obstacle at around

s and therefore switches to the

Collision Avoidance Mode. To ensure a safe distance from the obstacle, the follower adjusts the lateral position of its virtual leader,

, and performs the avoidance maneuver. After the first avoidance, the follower returns to the original formation; however, it again detects a potential collision with the corner of the obstacle and repeats the maneuver by readjusting its lateral position. From the error graph in

Figure 14e, it can be quantitatively observed that UAV 4 temporarily deviates from the nominal formation during obstacle avoidance, with position errors of approximately

and

in sequence, before gradually reconverging to the desired formation.

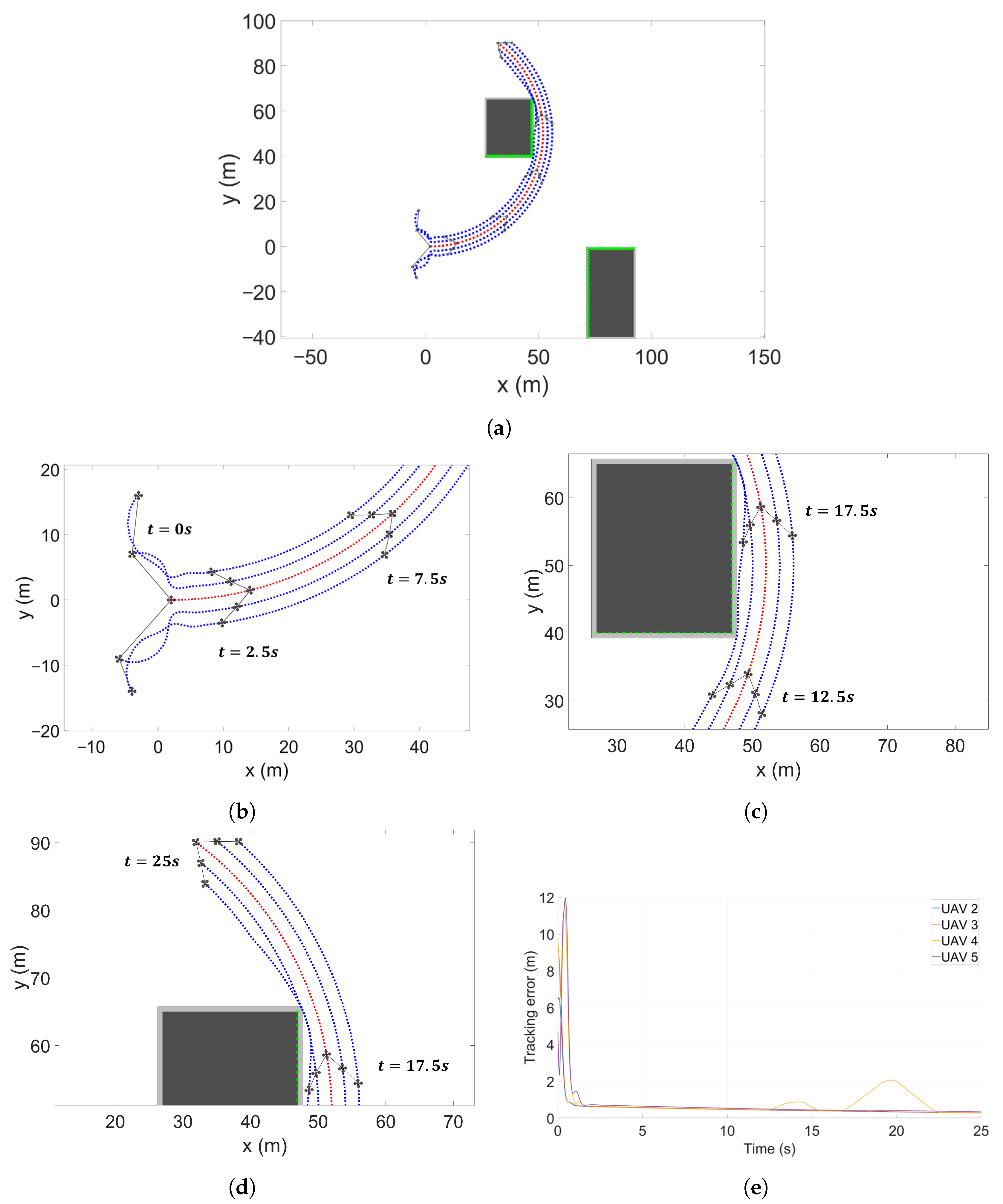

Next, the results of the straight-line flight simulation for the hexagonal formation are illustrated in

Figure 15. The followers establish a hexagonal formation within approximately

s. At

s, UAVs 3 and 5 switch to the

Collision Avoidance Mode, adjusting their lateral distance to

to modify the formation structure. The lateral positions of UAVs 6 and 7 are determined by the centroid positions of UAVs 2 and 3, and UAVs 4 and 5, respectively. Based on the time-varying

, the lateral positions of UAVs 6 and 7 are defined as in Equation (

20):

Although UAVs 6 and 7 do not require obstacle-avoidance maneuvers, their lateral distances are influenced by the avoidance actions of UAVs 3 and 5, as shown in

Figure 12 and Equation (

20), resulting in unnecessary movements. To mitigate these effects and preserve the desired formation as much as possible, UAVs 6 and 7 transitioned from the

Formation Tracking Mode to the

Formation Maintenance Mode. UAVs 3 and 5 transmit the changes in their virtual leader’s lateral position,

. Using these transmitted values, UAVs 6 and 7 readjust their virtual leader positions as described in Equation (

21):

By adjusting their virtual leader positions according to the lateral displacement of their respective leaders, UAVs 6 and 7 are able to maintain the original formation. This is quantitatively verified in the error graph of

Figure 15e, where UAVs 3 and 5 exhibit a maximum error of

during collision avoidance, while UAVs 6 and 7 show a maximum error of

in order to preserve the desired formation.

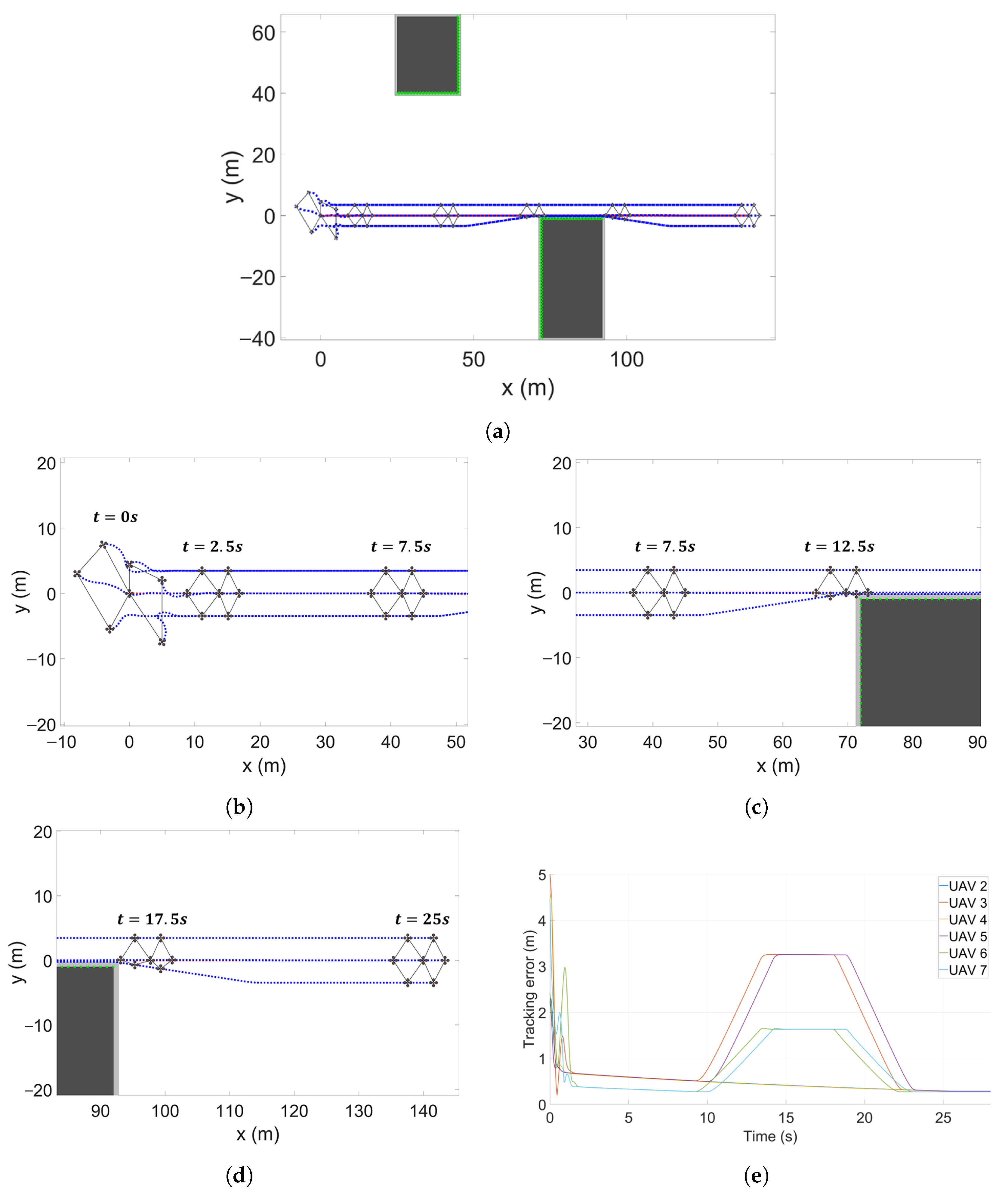

Figure 16 presents the simulation results for the hexagonal formation under circular motion. From these results, it is observed that the followers rapidly converge to the target formation and maintain a stable configuration even during two consecutive obstacle-avoidance scenarios. Furthermore, the error graph in

Figure 16e shows that, while UAVs 2 and 4 perform obstacle avoidance, UAVs 6 and 7 exhibit position errors to preserve the desired formation. This behavior occurs twice, corresponding to the two avoidance maneuvers.

The formation-flight results (

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16) for two scenarios—straight-line and circular motion—validated the performance of the proposed system. The follower UAVs successfully tracked their designated leaders while forming the specified shapes (V-shaped and hexagonal formation). In addition, each follower assessed potential collisions with obstacles relative to its leader and adjusted the virtual leader’s position to reconfigure the formation, thereby achieving effective obstacle avoidance. Furthermore, based on information received from its leader, each follower reduced unnecessary motions, improving the efficiency of the overall formation system.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a distributed leader–follower formation flight method for multiple UAV operations. Each UAV maintained the formation using relative bearing and distance information from its designated leader. The limitation of conventional bearing-based methods, which typically require at least two leaders, was addressed by introducing the concept of a virtual leader, enabling the entire formation to be managed efficiently with only a single leader. The proposed method was also shown to be scalable to various formation shapes and sizes through a hierarchical leader–follower structure. In addition, an obstacle-avoidance algorithm tailored to distributed formation operations was presented, addressing challenges such as obstacle avoidance, formation maintenance, and operational efficiency.

Numerical simulations were conducted for representative formation shapes, namely, V-shaped and hexagonal configurations. The results demonstrated that, regardless of initial positions and attitudes, the UAVs rapidly and stably converged to the desired formation while following the moving leader. Moreover, each UAV autonomously adjusted its position to avoid obstacles while minimizing unnecessary maneuvers, thereby enhancing the overall operational efficiency of the formation.

Nevertheless, in practical environments, communication delays between UAVs may arise due to network congestion or distance-related latency, potentially affecting the stability and performance of the proposed system. In addition, owing to the hierarchical leader–follower structure, errors may accumulate as the number of layers increases, causing the overall formation to deviate from the desired configuration. Furthermore, the possibility of collisions between followers or with obstacles during the initial convergence phase was not considered in this study.

Future work will extend the proposed framework to larger UAV formations and address complex issues such as communication delays, error accumulation, and potential collisions. In particular, the current framework does not guarantee collision avoidance among agents during convergence to the target formation. Therefore, future research will focus on developing a distributed collision avoidance strategy to ensure inter-agent safety. In parallel, to enable robust operation in more complex environments involving dynamic or irregular obstacles, a control barrier function (CBF)-based quadratic programming (QP) formulation, similar to that proposed by Huang [

37], will be incorporated. The system will be validated in ROS (Robot Operating System) and Gazebo to run simulations that incorporate real-world factors and enable more rigorous performance evaluation, and it will ultimately be validated on real hardware platforms.