An Effective Process to Use Drones for Above-Ground Biomass Estimation in Agroforestry Landscapes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

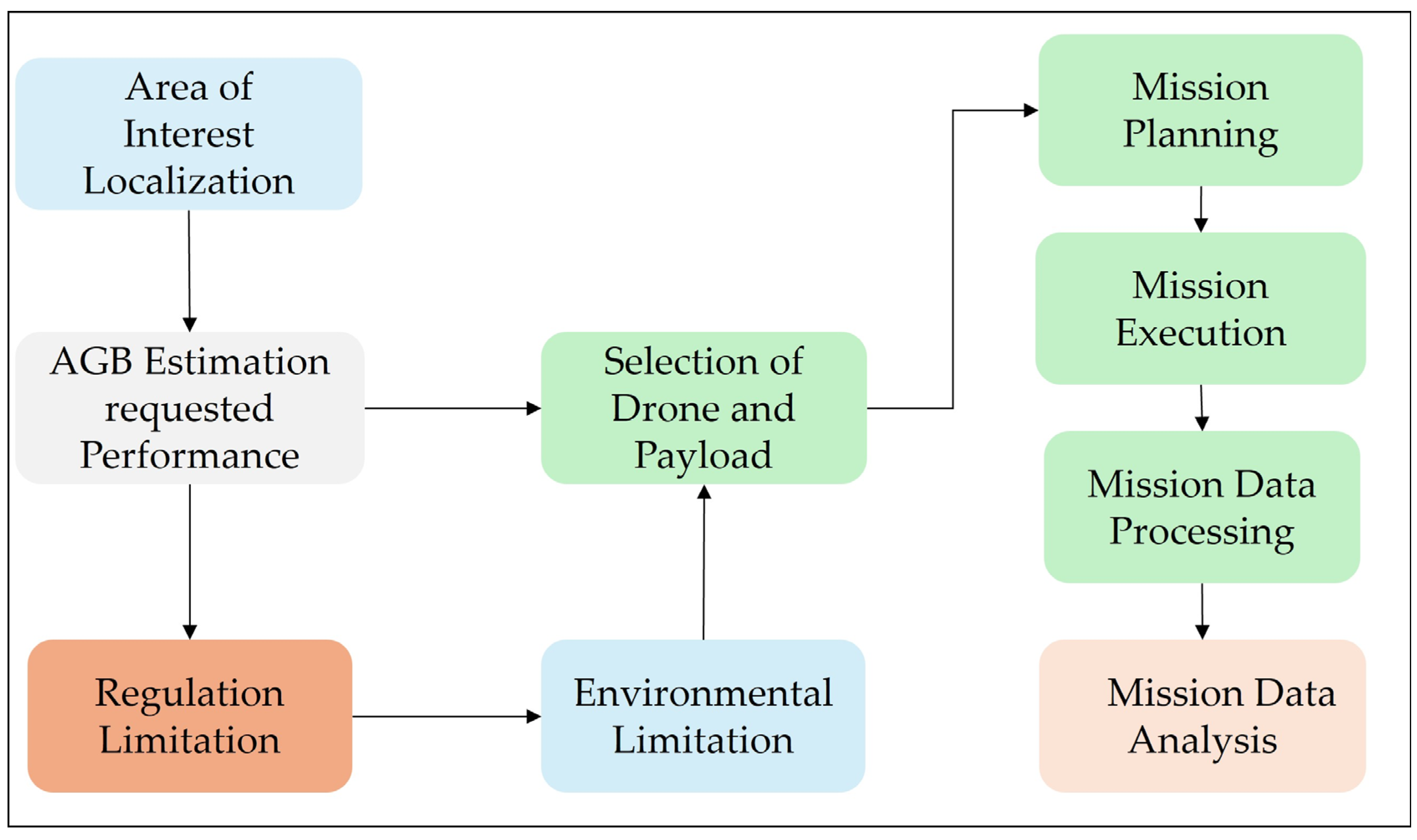

2.1. Problem Assessment

2.2. Methodology

3. Hardware Equipment and Software Tools

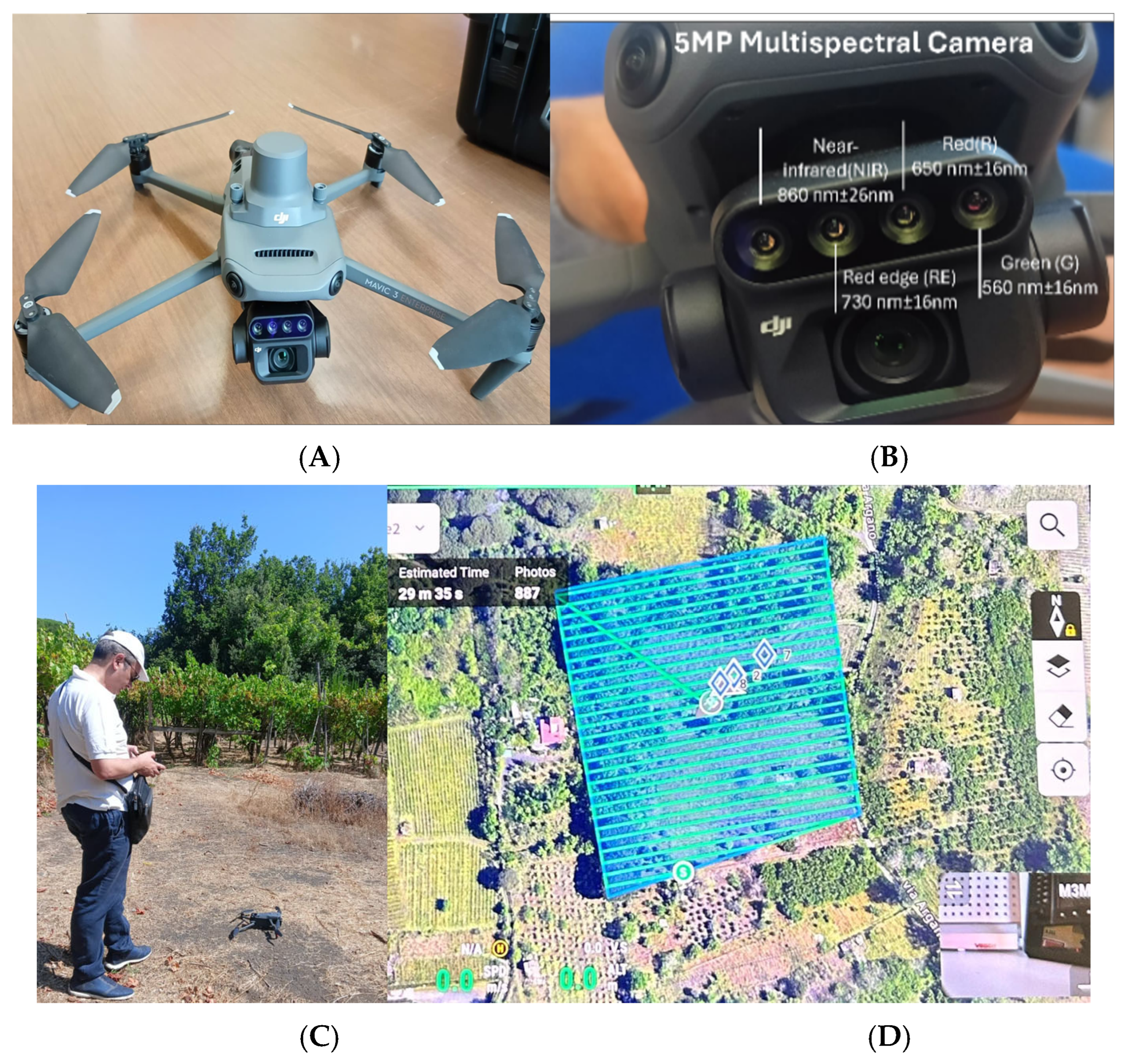

3.1. Drone Platform Selection

3.2. Payload Selection

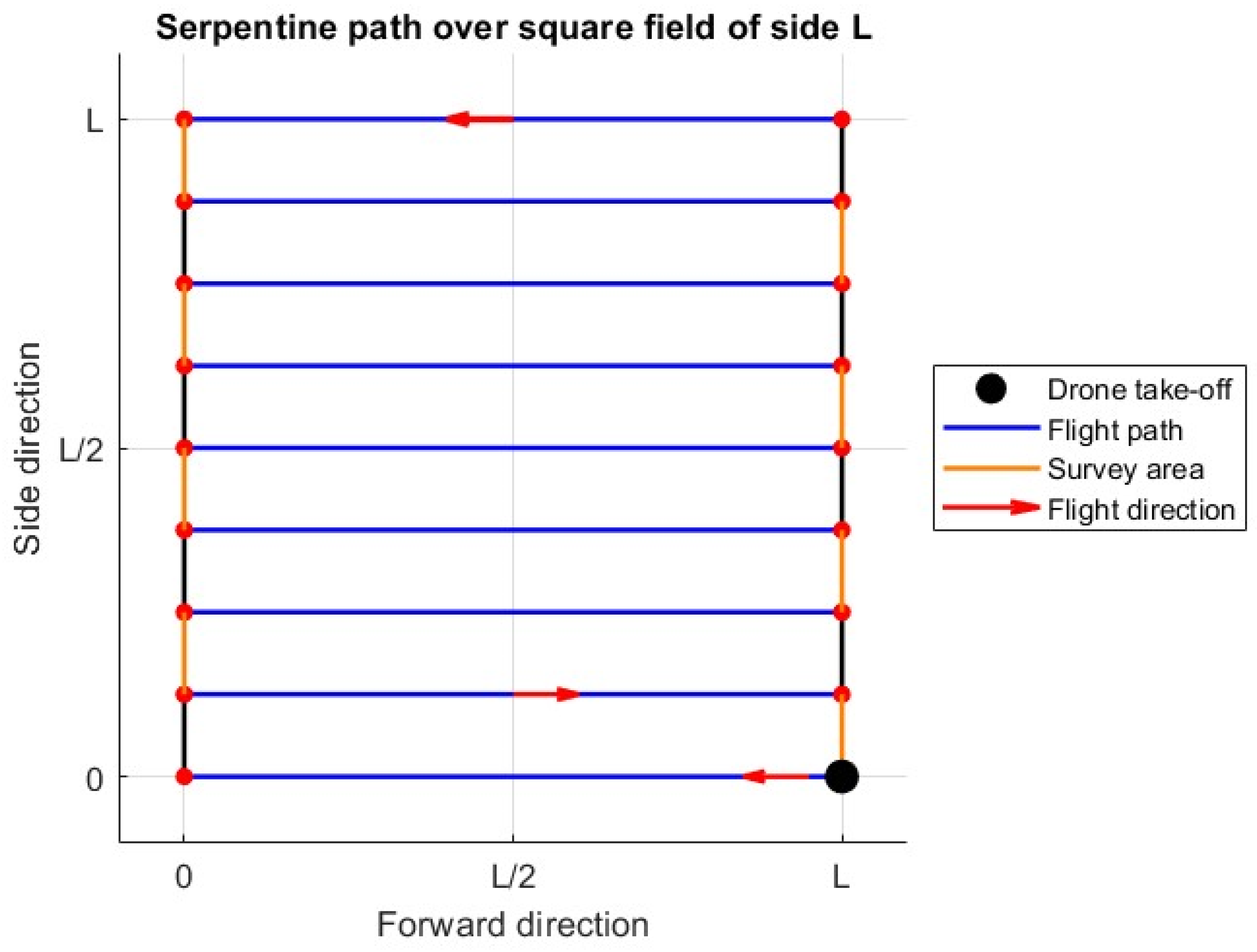

3.3. Mission Profile

- Flight overlap (front/side): Typically, 70–90% overlap is required for photogrammetric processing and vegetation index mosaicking.

- Lighting conditions: Influence illumination uniformly and shadow formation, particularly in RGB and multispectral acquisitions.

- Flight path orientation: Should align with crop rows or terrain slopes to improve interpretability and structural analysis.

- Repeatability and scheduling: Enables temporal monitoring of crop growth stages, stress dynamics, or seasonal variation.

3.4. Features of Interest: DBH, PH, and VIs

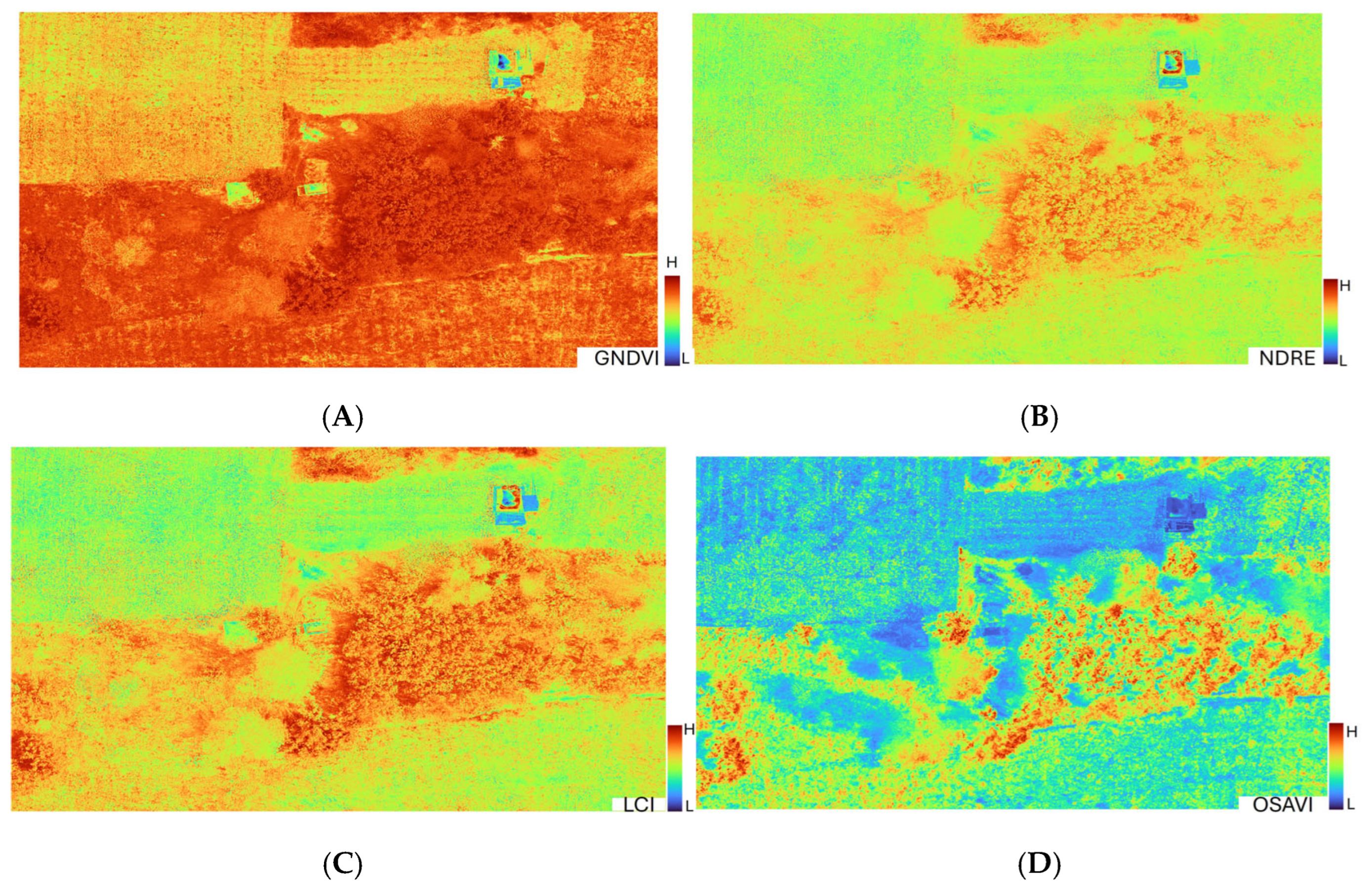

| Vegetation Indices/Bands | Formula | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Normalized Different Vegetation Index | [55] | |

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [55] | |

| Normalized Difference Red Edge | [55] | |

| Optimize Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | [56] | |

| Leaf Chlorophyll Index | [55] |

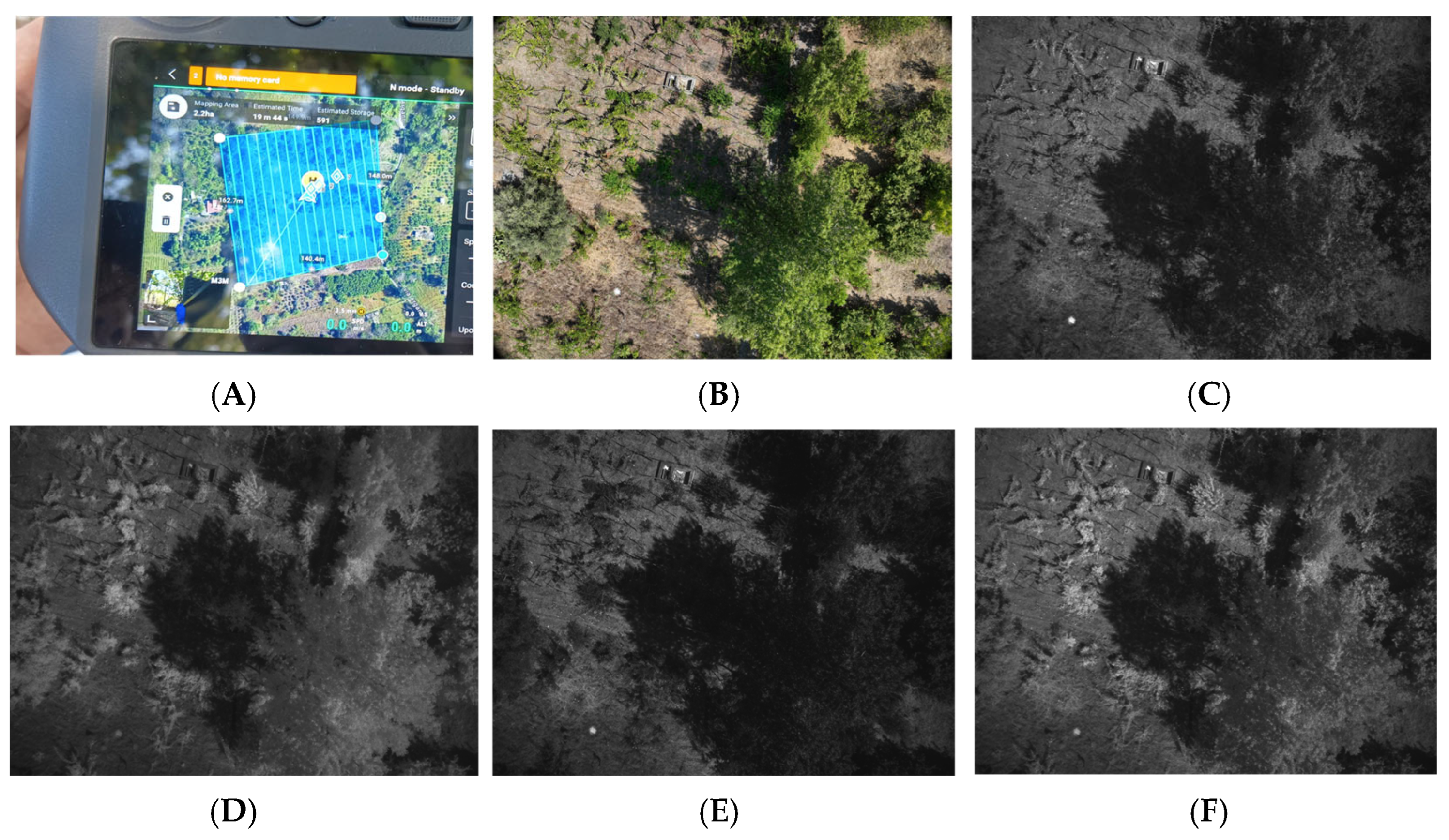

4. Mission Planning and Operational Execution

5. Data Analysis and Insights

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGB | Above-Ground Biomass |

| AGL | Above Ground Level |

| CHM | Canopy Height Model |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DBH | Diameter at Breast Height |

| DSM | Digital Surface Models |

| DLS | Downwelling Light Sensor |

| DTR | Decision Tree Regression |

| ExR | Excess Red Index |

| GCP | Ground Control Points |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GNDVI | Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| GSD | Ground Sampling Distance |

| LCI | Leaf Chlorophyll Index |

| LDR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| LIFT | Laboratory for Innovative Flight Technology |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| NDRE | Normalized Difference Red Edge Index |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| OSAVI | Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index |

| PH | Plant Height |

| PPK | Post-Processed Kinematic |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RGBRI | Red-Green-Blue Ratio Index |

| RGB | Red-Green-Blue |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RTK | Real-Time Kinematic |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| UAS | Unmanned Aircraft System/Systems |

| VI | Vegetation Indices |

| VEG | Vegetation Index |

| VTOL | Vertical Take-Off and Landing |

References

- Chave, J.; Andalo, C.; Brown, S.; Cairns, M.A.; Chambers, J.Q.; Eamus, D.; Fölster, H.; Fromard, F.; Higuchi, N.; Kira, T.; et al. ECOSYSTEM ECOLOGY Tree allometry and improved estimation of carbon stocks and balance in tropical forests. Oecologia 2005, 145, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, J.M.; Egipto, R.; Aguiar, F.C.; Marques, P.; Nogales, A.; Madeira, M. The role of soil temperature in mediterranean vineyards in a climate change context. Front. Media S.A. 2023, 14, 1145137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, R.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, H. A Simple Method Using an Allometric Model to Quantify the Carbon Sequestration Capacity in Vineyards. Plants 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, A.; Kumar, M.; Ram, J.; Meena, S. Agroforestry for Monetising Carbon Credits; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tamga, D.K.; Latifi, H.; Ullmann, T.; Baumhauer, R.; Thiel, M.; Bayala, J. Modelling the spatial distribution of the classification error of remote sensing data in cocoa agroforestry systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 97, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.N.; Morandé, J.A.; Vaghti, M.G.; Medellín-Azuara, J.; Viers, J.H. Ecosystem services in vineyard landscapes: A focus on aboveground carbon storage and accumulation. Carbon Balance Manag. 2020, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégué, A.; Arvor, D.; Bellon, B.; Betbeder, J.; De Abelleyra, D.; Ferraz, R.P.D.; Lebourgeois, V.; Lelong, C.; Simões, M.; Verón, S.R. Remote sensing and cropping practices: A review. Remote. Sens. 2018, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Bhardwaj, D.R.; Singh, M.K.; Nigam, R.; Pala, N.A.; Kumar, A.; Verma, K.; Kumar, D.; Thakur, P. Geospatial technology in agroforestry: Status, prospects, and constraints. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 116459–116487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Nie, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Ning, K. Carbon sequestration benefits of the grain for Green Program in the hilly red soil region of southern China. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021, 9, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, P.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Moreno, M.A.; Martínez-Moreno, A.; Ortega, J.F.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Ballesteros, R. Assessment of vineyard water status by multispectral and rgb imagery obtained from an unmanned aerial vehicle. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2021, 72, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poley, L.G.; McDermid, G.J. A systematic review of the factors influencing the estimation of vegetation aboveground biomass using unmanned aerial systems. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fern, R.R.; Foxley, E.A.; Bruno, A.; Morrison, M.L. Suitability of NDVI and OSAVI as estimators of green biomass and coverage in a semi-arid rangeland. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Karst vegetation coverage detection using UAV multispectral vegetation indices and machine learning algorithm. Plant Methods 2023, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, D.; Small, C. Linking Common Multispectral Vegetation Indices to Hyperspectral Mixture Models: Results from 5 nm, 3 m Airborne Imaging Spectroscopy in a Diverse Agricultural Landscape. Available online: https://github.com/isofit/isofit (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Panumonwatee, G.; Choosumrong, S.; Pampasit, S.; Premprasit, R.; Nemoto, T.; Raghavan, V. Machine learning technique for carbon sequestration estimation of mango orchards area using Sentinel-2 Data. Carbon Res. 2025, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamaoma, H.; Chirwa, P.W.; Ramoelo, A.; Hudak, A.T.; Syampungani, S. The Application of UASs in Forest Management and Monitoring: Challenges and Opportunities for Use in the Miombo Woodland. Forests 2022, 13, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfreda, S.; McCabe, M.F.; Miller, P.E.; Lucas, R.; Madrigal, V.P.; Mallinis, G.; Ben Dor, E.; Helman, D.; Estes, L.; Ciraolo, G.; et al. On the use of unmanned aerial systems for environmental monitoring. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, A.I.; Scholl, V.M.; McGlinchy, J.; Balch, J.; Cattau, M.E. A review of UAS-based estimation of forest traits and characteristics in landscape ecology. Landsc. Ecol. 2025, 40, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzo, C.O.G.; Kamali, B.; Hütt, C.; Bareth, G.; Gaiser, T. A Review of Estimation Methods for Aboveground Biomass in Grasslands Using UAV. Remote. Sens. 2023, 15, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, M.A.; Drijfhout, A.P.; Tesfamichael, S. Comparison of a fixed-wing and multi-rotor UAV for environmental mapping applications: A case study. In International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences-ISPRS Archives; International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2017; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Guo, J.; Xing, X.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Hou, Z.; Jia, Z.; Yang, X. Fusion of LiDAR and Multispectral Data for Aboveground Biomass Estimation in Mountain Grassland. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Lei, J.; Huang, Y. Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation Based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle–Light Detection and Ranging and Machine Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Vanko, J.; Hruška, J.; Adão, T.; Sousa, J.J.; Peres, E.; Morais, R. UAS, sensors, and data processing in agroforestry: A review towards practical applications. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 2349–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lian, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, F.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y. Accuracy Assessment of a UAV Direct Georeferencing Method and Impact of the Configuration of Ground Control Points. Drones 2022, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayushi, K.; Babu, K.N.; Ayyappan, N.; Nair, J.R.; Kakkara, A.; Reddy, C.S. A comparative analysis of machine learning techniques for aboveground biomass estimation: A case study of the Western Ghats, India. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 80, 102479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafkan, A.; Delavarpour, N.; Oduor, P.G.; Bandillo, N.; Flores, P. An Overview of Using Unmanned Aerial System Mounted Sensors to Measure Plant Above-Ground Biomass. Remote. Sens. 2023, 15, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WingtraOne Drone Technical Specifications. Available online: https://wingtra.com/mapping-drone-wingtraone/technical-specifications (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Guebsi, R.; Mami, S.; Chokmani, K. Drones in Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Applications, Technologies, and Challenges. Drones 2024, 8, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G.P.; Clark, J.K.; Mascaro, J.; García, G.A.G.; Chadwick, K.D.; Encinales, D.A.N.; Paez-Acosta, G.; Montenegro, E.C.; Kennedy-Bowdoin, T.; Duque, Á.; et al. High-resolution mapping of forest carbon stocks in the Colombian Amazon. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Zumpf, C.R.; Cacho, J.F.; Lee, D.; Lin, C.-H.; Boe, A.; Heaton, E.; Mitchell, R.; Negri, M.C. Remote sensing-based estimation of advanced perennial grass biomass yields for bioenergy. Land 2021, 10, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, C.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Zhai, W.; Mao, B.; Chen, Z. Precision estimation of winter wheat crop height and above-ground biomass using unmanned aerial vehicle imagery and oblique photoghraphy point cloud data. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1437350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzar, S.M.; Sherin, K.; Panthakkan, A.; Al Mansoori, S.; Al-Ahmad, H. Evaluation of UAV-Based RGB and Multispectral Vegetation Indices for Precision Agriculture in Palm Tree Cultivation. arxiv 2025, arXiv:2505.07840. [Google Scholar]

- DJI-Mavic-3M-Guide-1. Available online: https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/DJI_Mavic_3_Enterprise/20221216/DJI_Mavic_3M_User_Manual-EN.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Zhang, D.; Qi, H.; Guo, X.; Sun, H.; Min, J.; Li, S.; Hou, L.; Lv, L. Integration of UAV Multispectral Remote Sensing and Random Forest for Full-Growth Stage Monitoring of Wheat Dynamics. Agriculture 2025, 15, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hayder, Z.; Zia, A.; Cassidy, C.; Liu, S.; Stiller, W.; Stone, E.; Conaty, W.; Petersson, L.; Rolland, V. NeFF-BioNet: Crop Biomass Prediction from Point Cloud to Drone Imagery. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.23901. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Mustafa, G.; Su, X.; Nian, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhen, F.; Wang, W.; Li, X. UAV Remote Sensing Technology for Wheat Growth Monitoring in Precision Agriculture: Comparison of Data Quality and Growth Parameter Inversion. Agronomy 2025, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, C.; Bai, X.; Dong, L.; Tan, Y.; Yusup, M.; Akelebai, G.; Dong, H.; Zhi, J. Effects of solar elevation angle on the visible light vegetation index of a cotton field when extracted from the UAV. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badagliacca, G.; Messina, G.; Praticò, S.; Presti, E.L.; Preiti, G.; Monti, M.; Modica, G. Multispectral Vegetation Indices and Machine Learning Approaches for Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Yield Prediction across Different Varieties. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 2032–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, L.; Eeckhout, E.; Wieme, J.; Dejaegher, Y.; Audenaert, K.; Maes, W.H. Identifying the Optimal Radiometric Calibration Method for UAV-Based Multispectral Imaging. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DJI Assistant 2(Enterprise Series) Release Note. Available online: https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/dji_assistant/20250609/DJI+Assistant+2+(Enterprise+Series)+Release+Notes(V2.1.17).pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Xie, J.; Shen, Y.; Cen, H. Real-time reflectance generation for UAV multispectral imagery using an onboard downwelling spectrometer in varied weather conditions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.19527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.C.; Wulder, M.A.; Varhola, A.; Vastaranta, M.; Coops, N.C.; Cook, B.D.; Pitt, D.; Woods, M. A best practices guide for generating forest inventory attributes from airborne laser scanning data using an area-based approach. Can. Inst. For. 2013, 89, 722–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.R.; Kershaw, J.A. Estimating diameter and height distributions from airborne lidar via copulas. Math. Comput. For. Nat.-Resour. Sci. 2021, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tupinambá-Simões, F.; Pascual, A.; Guerra-Hernández, J.; Ordóñez, C.; Barreiro, S.; Bravo, F. Combining hand-held and drone-based lidar for forest carbon monitoring: Insights from a Mediterranean mixed forest in central Portugal. Eur. J. For. Res. 2025, 144, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan-Ovejero, R.; Elghouat, A.; Navarro, C.J.; Reyes-Martín, M.P.; Jiménez, M.N.; Navarro, F.B.; Alcaraz-Segura, D.; Castro, J. Estimation of aboveground biomass and carbon stocks of Quercus ilex L. saplings using UAV-derived RGB imagery. Ann. For. Sci. 2023, 80, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Han, W.; Peng, X. Estimating above-ground biomass of maize using features derived from UAV-based RGB imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, R.; Maimaitijiang, M.; Chang, J.; Caffe, M. Utilizing Spectral, Structural and Textural Features for Estimating Oat Above-Ground Biomass Using UAV-Based Multispectral Data and Machine Learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 9708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, S.; Sakamoto, T.; Imase, R.; Nonoue, Y.; Tsunematsu, H.; Goto, A.; Matsushita, K.; Ohmori, S.; Maeda, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; et al. Prediction of heading date, culm length, and biomass from canopy-height-related parameters derived from time-series UAV observations of rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 998803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, N.; Kafashan, J. UAV-based remote sensing in orcha-forest environment; diversity of research, used platforms and sensors. Remote. Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 32, 101068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonen, A.A.; Accardo, D.; Renga, A. Above Ground Biomass Estimation in Agroforestry Environment by UAS and RGB Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, MetroAeroSpace 2024-Proceeding, Lublin, Poland, 3–5 June 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, L.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Deng, L. Improving AGB estimations by integrating tree height and crown radius from multisource remote sensing. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maesano, M.; Santopuoli, G.; Moresi, F.; Matteucci, G.; Lasserre, B.; Mugnozza, G.S. Above ground biomass estimation from UAV high resolution RGB images and LiDAR data in a pine forest in Southern Italy. iForest-Biogeosci. For. 2022, 15, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamahewage, S.H.G.; Witharana, C.; Riemann, R.; Fahey, R.; Worthley, T. Aboveground biomass estimation using multimodal remote sensing observations and machine learning in mixed temperate forest. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shi, S.; Liao, Z.; Wang, T.; Gong, W.; Shi, Z. Estimation of woody vegetation biomass in Australia based on multi-source remote sensing data and stacking models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneros, J.; Chavez, S.; Oliva, M.; Arellanos, E.; Maicelo, J.L.; García, L. Comparing Six Vegetation Indexes between Aquatic Ecosystems Using a Multispectral Camera and a Parrot Disco-Pro Ag Drone, the ArcGIS, and the Family Error Rate: A Case Study of the Peruvian Jalca. Water 2023, 15, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leolini, L.; Moriondo, M.; Rossi, R.; Bellini, E.; Brilli, L.; López-Bernal, Á.; Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Bindi, M.; Dibari, C.; et al. Use of Sentinel-2 Derived Vegetation Indices for Estimating fPAR in Olive Groves. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonen, A.A.; Accardo, D.; Renga, A. Above-Ground Biomass Prediction in Agroforestry Areas Using Machine Learning and Multispectral Drone Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 12th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace (MetroAeroSpace), Naples, Italy, 18–20 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Unit/Details | Purpose/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Drone platform | Multispectral Payload | Multispectral data acquisition |

| Sensor spectral bands | NIR, Red Edge, Red, Green; 10-bit radiometric resolution | Capture vegetation reflectance for indices |

| Ground Sampling Distance (GSD) | cm/pixel | Defines the spatial detail of imagery |

| Flight altitude | meters (m) | Affects GSD and coverage |

| Flight speed | m/s | Ensures image sharpness and overlap |

| Image overlap | % (front lap/side lap) | Ensures complete coverage and mosaicking |

| Coverage area | ha or m2 | Area surveyed per mission |

| Georeferencing | RTK/PPK, GCPs | Ensures spatial accuracy of imagery |

| Environmental light | Sun angle (°), cloud cover (%) | To minimize shadows, maintain consistent illumination, and ensure radiometric accuracy of spectral data. |

| Time/Seasonality | Date, crop growth stage | Capturing data under similar phenological stages and lighting conditions. |

| Vegetation indices | NDVI, NDRE, GNDVI, LCI and OASVI | Quantifies vegetation status and biomass |

| Post-processing | Orthomosaic,3D-model, DEM/DSM | Generates final data products for analysis |

| Parameter | RGB Sensor | Multispectral Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| FOV H × V (deg) | 73.2° × 53.0° | 61.2° × 48.1° |

| Array size H × V (pixels) | 5280 × 3956 | 2592 × 1944 |

| Parameter | Raw Requirement | Mavic 3M Specification | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platform Type | Multirotor | Multirotor | Optimal for small to medium agroforestry plots |

| Flight Time | 30–43 min | 30 min | Single-flight mapping capability |

| GPS Accuracy | RTK/PPK | RTK included | High-precision mapping |

| Sensor Compatibility | Multispectral, RGB, optional LiDAR | 5 multispectral bands + RGB sensor | Suitable for vegetation indices and structure modeling |

| Ground Sampling Distance | ≤10 cm/pixel | RGB: 0.6 cm/pixel; Multispectral 1.1 cm/pixel | High-resolution image acquisition |

| Autonomous Flight Capability | Pre-set path with terrain adaptation | via DJI Pilot 2 with built-in flight planning | Enables consistent, repeatable flights |

| Weather Tolerance | ≥20 km/h Wind resistance | 43 km/h Wind resistance | Robust for typical agroforestry conditions |

| Data Storage | ≥64 GB | up to 512 GB microSD | Sufficient for large image datasets |

| Software | Primary Function | Integration/Workflow Role |

|---|---|---|

| DJI Pilot 2™ | Flight planning and mission execution | Data acquisition from UAV platforms |

| DJI Terra/Agisoft Meta-shape | Orthomosaic generation and 3D reconstruction | Photogrammetric processing |

| QGIS | Feature extraction and visualization | GIS integration and spatial analysis |

| Python | Data modeling and automation | Workflow automation and custom analysis pipelines |

| Parameter | Raw Requirement | Mavic 3M Specification | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Type | Multispectral + RGB (optionally thermal or LiDAR) | 4 Multispectral Bands + RGB | Meets standard for vegetation analysis |

| Sensor Integration | Integrated with minimal setup | Fully integrated sensors | Simplify operation |

| Payload Weight Capacity | ≥500 g (if external sensor required) | Built-in sensors | No external payload required |

| Data Synchronization | Time-synchronized with GPS/IMU | GNSS + RTK synchronized | Ensures geospatial accuracy |

| Spectral Resolution | Bands suitable for VI:-NDVI, GNDVI, NDRE, LCI and OSAVI. | RGB, Green, Red, Red Edge, NIR | Suitable for AGB vegetation calculation |

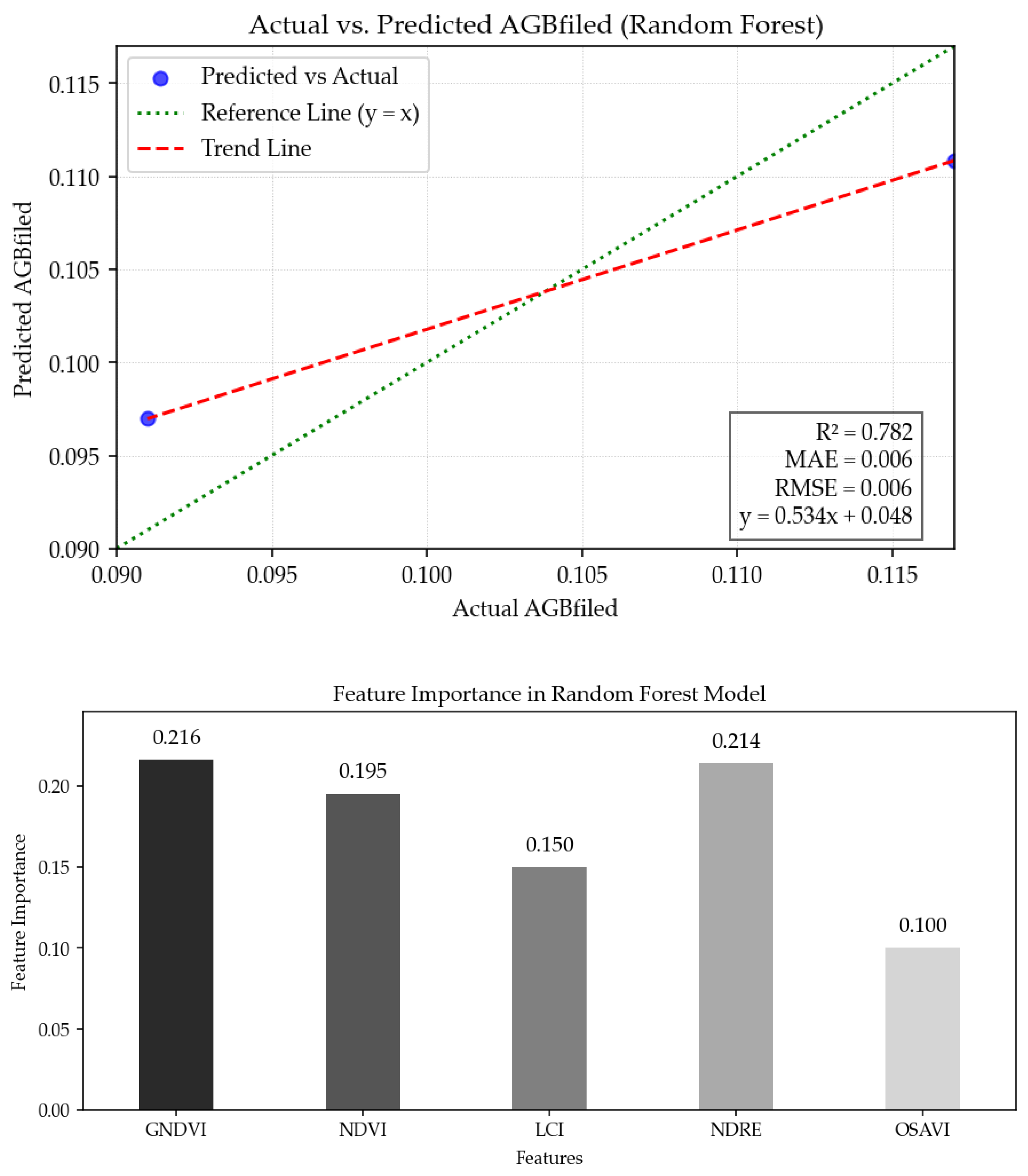

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| R2 Score | 0.782 | Proportion of AGB variance explained by the model |

| MAE | 0.006 | Mean Absolute Error: Average size of prediction errors (in AGB units) |

| RMSE | 0.006 | Root Mean Square Error: standard deviation of prediction errors |

| Trend line Equation | The regression fits between actual and predicted AGB field values |

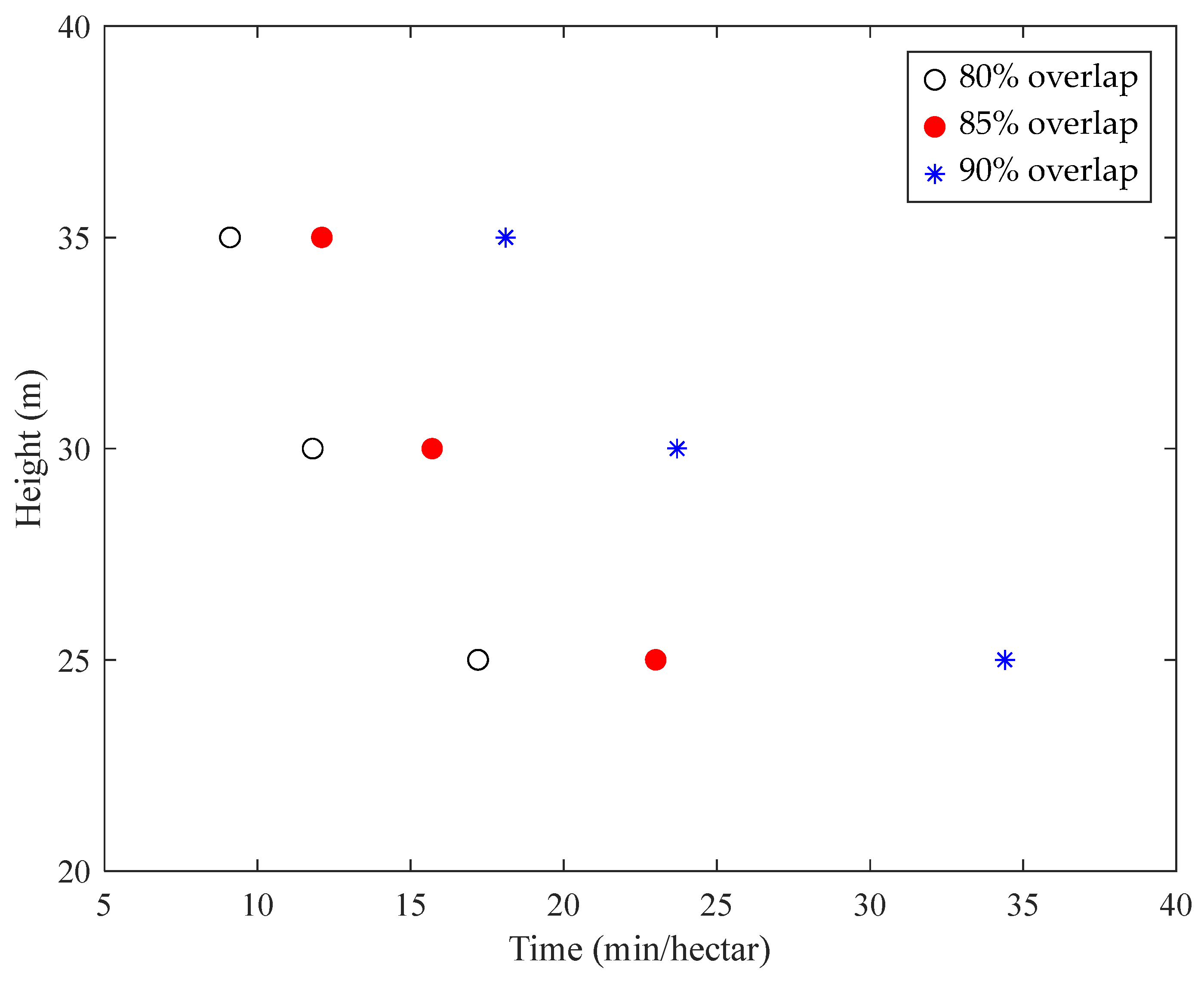

| Altitude [m] | Front % Overlap | GSD Multispectral [cm/Pixel] | GSD RGB [cm/Pixel] | Swath Width Multispectral [m] | Average Speed [m/s] | Mission Time [min/Hectares] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 80% | 1.1 cm/px | 0.6 cm/px | 22.3 | 2.2 | 17.2 |

| 25 | 85% | 1.1 cm/px | 0.6 cm/px | 22.3 | 1.7 | 23.0 |

| 25 | 90% | 1.1 cm/px | 0.6 cm/px | 22.3 | 1.1 | 34.4 |

| 30 | 80% | 1.4 cm/px | 0.8 cm/px | 26.8 | 2.7 | 11.8 |

| 30 | 85% | 1.4 cm/px | 0.8 cm/px | 26.8 | 2.0 | 15.7 |

| 30 | 90% | 1.4 cm/px | 0.8 cm/px | 26.8 | 1.3 | 23.7 |

| 35 | 80% | 1.6 cm/px | 0.9 cm/px | 31.2 | 3.1 | 9.1 |

| 35 | 85% | 1.6 cm/px | 0.9 cm/px | 31.2 | 2.3 | 12.1 |

| 35 | 90% | 1.6 cm/px | 0.9 cm/px | 31.2 | 1.6 | 18.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mekonen, A.A.; Conte, C.; Accardo, D. An Effective Process to Use Drones for Above-Ground Biomass Estimation in Agroforestry Landscapes. Aerospace 2025, 12, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111001

Mekonen AA, Conte C, Accardo D. An Effective Process to Use Drones for Above-Ground Biomass Estimation in Agroforestry Landscapes. Aerospace. 2025; 12(11):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111001

Chicago/Turabian StyleMekonen, Andsera Adugna, Claudia Conte, and Domenico Accardo. 2025. "An Effective Process to Use Drones for Above-Ground Biomass Estimation in Agroforestry Landscapes" Aerospace 12, no. 11: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111001

APA StyleMekonen, A. A., Conte, C., & Accardo, D. (2025). An Effective Process to Use Drones for Above-Ground Biomass Estimation in Agroforestry Landscapes. Aerospace, 12(11), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111001