1. Introduction

One of the fundamental problems in feedback control design is the ability to address discrepancies between system models and real-world systems. To this end, adaptive control has been developed to address the problem of system uncertainty in control-system design [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In particular, adaptive control is based on constant linearly parameterized system uncertainty models of a known structure but unknown variation and, in the case of indirect adaptive control, combines an online parameter estimation algorithm with a control law to improve performance in the face of system uncertainties. More specifically, indirect adaptive controllers utilize parameter update laws to identify unknown system parameters and adjust feedback gains to account for system uncertainty.

The parameter estimation algorithms that have been typically used in adaptive control are predicated on two gradient descent type methods that update the system parameter errors in the direction that minimizes a prediction error for a specified cost function. Namely, for a

gradient descent flow algorithm, the cost function involves an instantaneous prediction error between an estimated system output and the actual system output of the most recent data, whereas for an

integral gradient descent algorithm the cost function captures an aggregate of the past prediction errors in an integral form while placing more emphasis on recent measurements [

2].

Additionally, the recursive least squares (RLS) algorithm [

2] has also been used for parameter estimation and has been shown to give superior convergence rates as compared to the classical gradient descent algorithms. RLS algorithms can be viewed as a gradient descent method with a time-varying learning rate [

5]. For static (i.e., time-invariant) cost functions,

momentum-based methods, also known as

higher-order tuners, such as the Nesterov method, have been shown to achieve faster parameter error convergence as compared to traditional gradient descent algorithms [

6]. Since faster convergence can lead to improved transient system performance, there has been a significant interest in extending momentum-based methods to time-varying cost functions, which naturally appear in adaptive control formulations [

7,

8,

9].

Specifically, in [

7] momentum-based architectures were merged with the standard gradient descent method using a variational approach to guarantee boundedness for the parameter estimation and model reference adaptive control problems involving time-varying regressors. Higher-order tuners were also shown to provide an additional degree of freedom in the design of adaptive control laws [

10,

11]. Given that integral gradient and recursive least squares algorithms provide superior noise rejection properties and improved system performance to that of standard gradient descent methods, there has been a recent interest in integrating momentum-based architectures into adaptive laws for parameter identification and control [

5,

7].

In this paper, we develop new continuous-time, momentum-based adaptive laws for identification and control by augmenting higher-order tuners into the integral gradient, recursive least squares and composite gradient algorithms. Specifically, in

Section 2, we first review the existing gradient-based and momentum-based update laws and introduce three new higher-order tuner architectures. Next, in

Section 3, we show how these update laws can be applied for parameter identification, and then, in

Section 4, we introduce a momentum-based recursive least squares (MRLS) algorithm for model reference adaptive control. Finally,

Section 5 provides several numerical examples that highlight the improved parameter error convergence rate of the proposed momentum-based update laws.

The notation used in this paper is standard. Specifically, we write to denote the set of column vectors, to denote the set of real matrices, and to denote transpose. The equi-induced 2-norm of a matrix is denoted as where denotes the maximum eigenvalue and denotes the maximum singular value. We write (resp., ) for the minimum eigenvalue (resp., singular value), for the gradient of a scalar-valued function V with respect to a vector-valued variable x, and for the Laplace transform of , that is . Finally, we write to denote the proper rational functions with coefficients in (i.e., SISO proper rational transfer functions), to denote polynomials with real coefficients, to denote the space of square-integrable Lebesgue measurable functions on , and to denote the space of bounded Lebesgue measurable functions on .

2. From First-Order to Higher-Order Tuners for Parameter Estimation

Consider the system given by

where, for

,

is the system output,

is a time-varying regressor vector, and

is an unknown system parameter vector. Here we assume that

is bounded, and hence, can be normalized via the scaling factor

so that, with a minor abuse of notation,

. Since

is unknown, we design an estimator of the form

, where

, is an estimate of

, so that the prediction error between the estimated output

, and the actual system output

, is given by

where

is the parameter estimation error.

For the error system (

2), consider the quadratic loss cost function

and note that the gradient of

L with respect to the parameter estimate

is given by

. In this case, the gradient flow algorithm is expressed as

where

is a weighting gain parameter. As shown in [

7],

for all

.

It is well known that the rate of convergence for the gradient flow algorithm (

4) can be slow [

6]. However, if the regressor vector

satisfies a persistency of the excitation condition, then

converges to

exponentially with a convergence rate proportional to

. Although in this case the convergence rate can improve significantly, large values of

can result in a stiff initial value problem for (

4) necessitating progressively smaller sampling times for implementing (

4) on a digital computer. Furthermore, small sampling times can increase the sensitivity of the adaptive law to measurement noise and modeling errors [

2]. To address these limitations, momentum-based accelerated algorithms predicated on higher-order tuner laws are introduced in [

7] to expedite parameter estimation error convergence.

In [

12], an array of accelerated methods for continuous-time systems are derived using a Lagrangian variational formulation. Building on this work, [

7] extends the variational framework of [

12] to address a time-varying instantaneous quadratic loss function of the form given by (

3). Specifically, a Lagrangian of the form

is introduced, where

,

is a

friction coefficient, and

, and the functional

where

is a finite-time interval, is considered. A necessary condition for

minimizing (

6) is shown in [

7] to satisfy

Note that (

7) can be rewritten as

where

is an auxiliary parameter and

. The stability properties of (

8) and (9) are given in [

7]. Taking the limiting case as

, the gradient flow algorithm (

4) can be recovered as a special case of (

8) and (9).

Rather than relying solely on the instantaneous system measurement

, the loss cost function (

3) can be modified to incorporate a weighted sum of past system measurements. Specifically, we can consider loss cost functions in the form of (see [

2])

where

is a

forgetting factor that prevents the degeneration of system information updates in some direction by placing more emphasis on the more recent measurements. In this case, the gradient of the loss cost function (

10) is given by

where

Now, setting

we obtain the

integral gradient algorithm ([

2])

The stability properties of (

15)–(17) are addressed in [

2] ([Thm. 3.6.7]).

Next, motivated by the variational formulation of [

7] we introduce a momentum-based integral gradient algorithm. Specifically, defining the Lagrangian

where

, and using the Euler-Lagrange equation, a necessary condition for

minimizing (

6) yields

where, for

,

and

are given by (

12) and (13). Note that (

19) can be rewritten as

where

is an auxiliary parameter and

. Furthermore, (

20) and (21) can be rewritten in terms of the parameter estimation error

, and the auxiliary parameter estimation error

as

The following definition and lemmas are needed for the main results of this section.

Definition 1. A vector signal is persistently excited (PE) if there exist a positive constant ρ and a finite-time such that Lemma 1. Consider the system (22). Then, the following statements hold:

If is persistently excited, then Proof. To show

, note that it follows from (

12) and

, that

which proves (

27). Next, to show (

, note that if

is PE, then

This proves the lemma. □

Lemma 2 ([

3])

. Let . If and , then . Theorem 1. Let , and consider the momentum-based integral gradient algorithm (20)–(23). Then, the following statements hold: , , and .

If is persistently excited, then converges to exponentially as with a convergence rate of , where .

Proof. To show

, consider the positive-definite function

and note that

which, since

, implies

. Thus,

and

.

Next, integrating

over

yields

and hence,

. Similarly,

, and hence,

. Since (

27) implies that

, it follows that

. Now, it follows from (

24) and (25) that

,

. Finally, since

, it follows that

,

, and, by Lemma 2, it follows that

.

Next, to show (

, it follows from (

28) and (

30) that

which implies that

Now, (

31) implies that, for all

,

and hence, using the triangle inequality

, it follows that

which proves that

converges to 0 exponentially as

with a convergence rate of

. □

Remark 1. Note that unlike gradient flow and recursive least squares algorithms, the momentum-based integral gradient algorithm (20)–(23) does not require the assumption that in order to guarantee that [7]. Remark 2. Note that a time-varying forgetting factor can also be employed in (22) and (23). In this case, the PE condition can be replaced with a less restrictive excitation condition where (26) holds for a fixed-time t and not for all [13]. Next, we consider the cost function

where for all

is an

nonnegative-definite matrix function called the

general forgetting matrix and

is an

positive-definite matrix. It can be shown that a necessary condition for

minimizing (

33) gives the

recursive least squares algorithm ([

14])

Note that setting

and

, where

is positive-definite for all

(see [

2]), we recover, respectively, the

pure recursive least squares and the

recursive least squares with exponential forgetting algorithms discussed in [

2].

Note that the RLS algorithms (

34) and (35) do not involve a gradient flow architecture, and the variational formulation cannot be used to generate a momentum-based recursive least squares (MRLS) algorithm. Despite this fact, higher-order tuner laws can still be incorporated into the RLS architecture to give the MRLS architecture

where

and

,

. Note that (

36) and (37) can be rewritten as

Noting that

and using the fact that

it follows that

Lemma 3. Consider the system (42) with . Then, the following statements hold: where . If is persistently excited, thenwhere . Proof. To show

, note that it follows from (

42) with

that

Now, using

yields

which proves (

43).

Next, to show (

, note that if

is PE, then

and

Thus,

This proves the lemma. □

Theorem 2. Let , and consider the momentum-based recursive least squares algorithm (36)–(38). Then, given by (2) satisfies . Furthermore, the following statements hold: If there exists such that (44) holds, then , . If, in addition, , then and . If and is persistently excited, then the zero solution to (39) and (40) is exponentially stable. Proof. Consider the function

and note that

Now, by the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality,

and hence,

Next, integrating

over

yields

and hence,

.

To show (

i), note that (

49) and (

44) imply that

and

. In addition, (37) implies that

, and for

, it follows from (

2) and Lemma 2 that

and

.

Finally, to show

, note that if

is persistently excited, then (

44) holds by Lemma 1. Now, using the fact that

where

is a positive-definite matrix with eigenvalues

, it follows from the Schur decomposition that

and hence,

In this case, (

49) gives

which shows that the zero solution

to (

39) and (40) is exponentially stable [

15] ([Theorem 4.6]). □

Remark 3. Note that settingguarantees that (44) holds [14]. The constraints on parameter

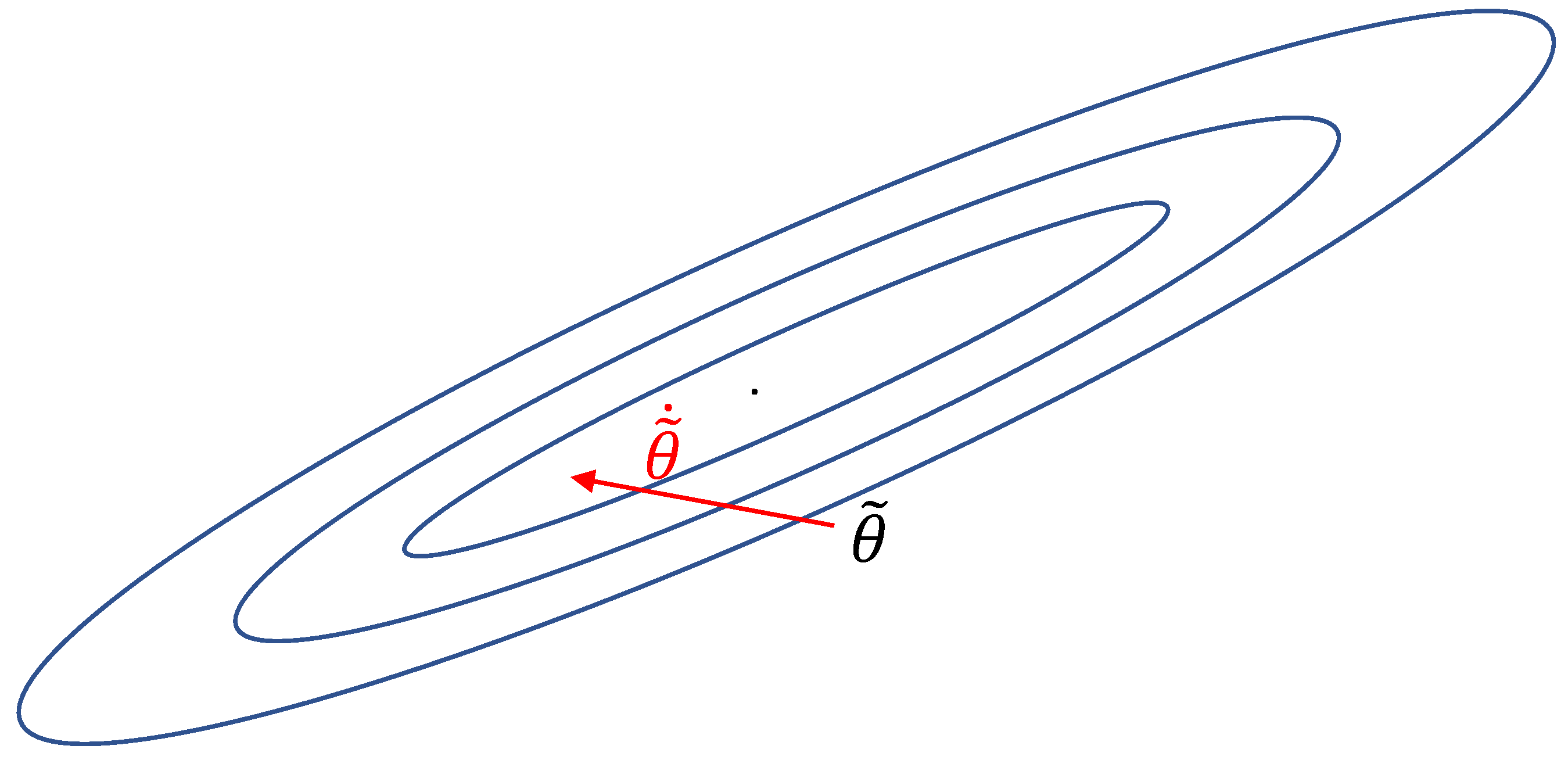

in Theorems 1 and 2 limit the amount of momentum that can be applied, thereby limiting the potential advantage gained by using a momentum-based algorithm. In the context of static optimization, Lyapunov-like functions are typically constructed as the sum of two terms; one term representing the norm of the error of the parameter estimate and the other term corresponding to the loss cost function [

12]. This generalized structure allows for adjustments to the parameter estimate

, that may not decrease

or

but can reduce the loss cost function

as shown in

Figure 1.

In order to incorporate (

10) in our Lyapunov function, we introduce the

momentum-based composite gradient algorithm

where

and

are given by (

12) and (13). Note that this composite update law includes an integral gradient term as well as a recursive least squares term in (

55).

Theorem 3. Let , and consider the momentum-based composite gradient algorithm (55)–(57). Then, the following statements hold: If there exists such that (44) holds, then , , and . If and is persistently excited, then the zero solution to (55)–(57) is exponentially stable. Proof. This proof is similar to the proof of Theorem 2. Namely, consider the positive-definite function

satisfying

, and note that

Now, using (

49) and (

59), note that

now follows using similar arguments as in the proof of Theorem 2.

To show

, note that if

is persistently excited, then (

44) and (

51) hold, and hence, using the fact that

, we have

Now, using (

49) and (

60), it follows that the zero solution

to (

55) and (56) is exponentially stable [

15] ([Theorem 4.6]). □

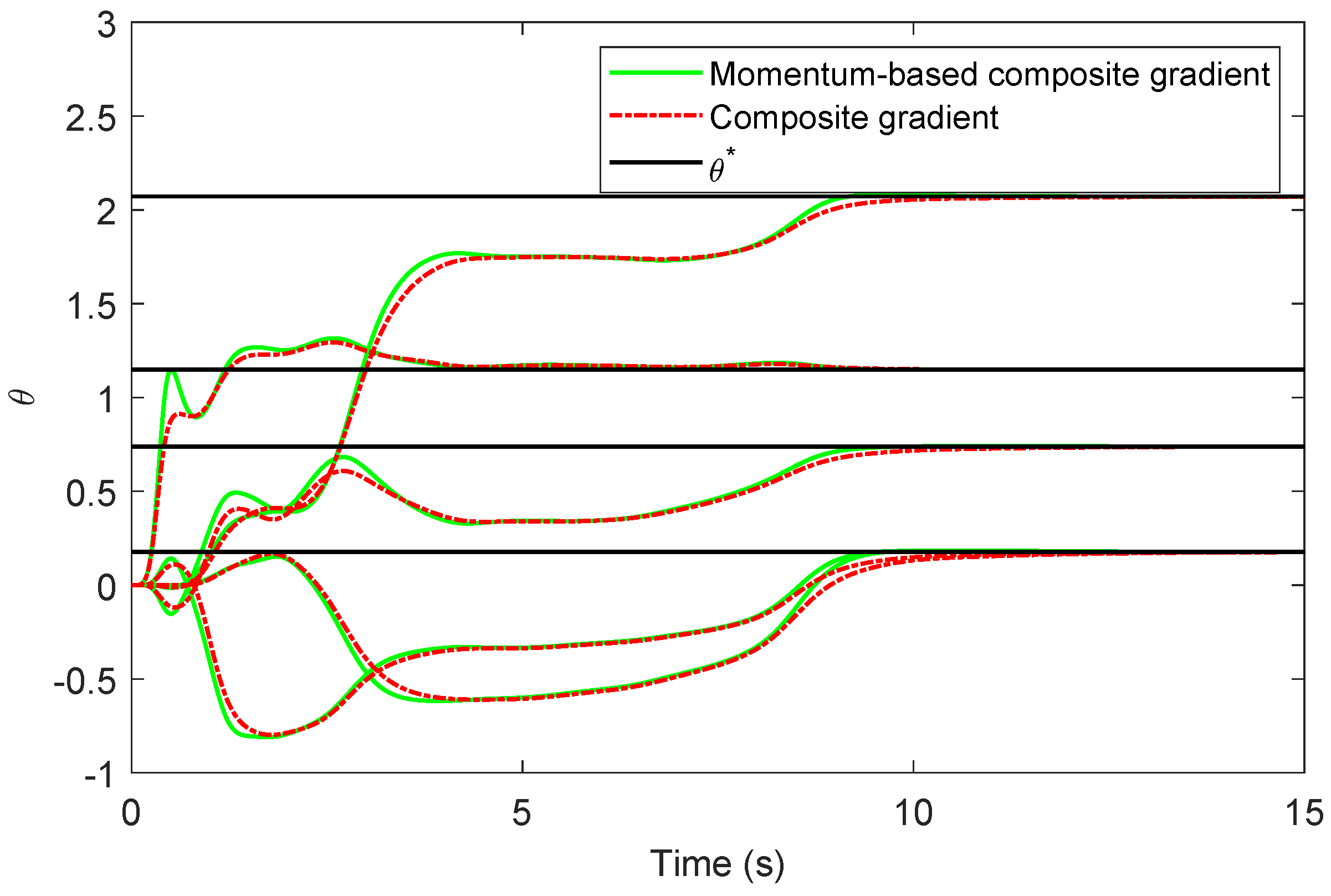

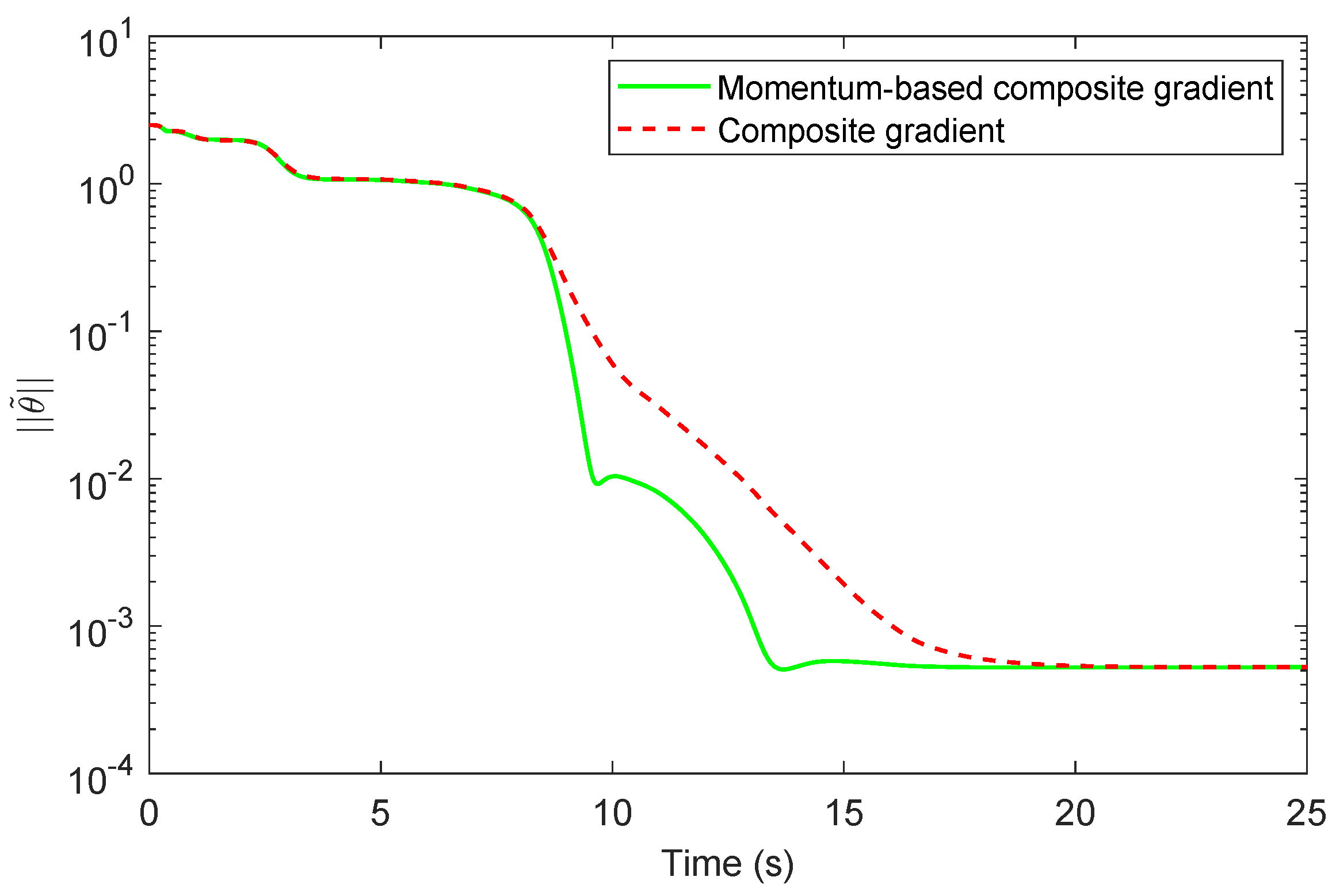

3. System Parameter Identification

In this section, we address the problem of parameter identification using the first- and higher-order tuner algorithms developed in

Section 2. First, the following definition is needed.

Definition 2 ([

2])

. A signal is stationary and sufficiently rich of order n if the following statements hold: The limitexists uniformly in . The support of the spectral measure , of u contains at least n points.

Consider the stable single-input, single-output (SISO) plant, with output

and input

being the only available signals for measurement, given by

where

,

, and

. Since there are an infinite number of triples (

) yielding the same input–output measurements, we cannot uniquely define the

coefficients in (

). However, we can determine the

parameters corresponding to the coefficients of the stable and strictly proper rational transfer function

given by

where, for

,

is the system output,

is the system input, and the coefficients

,

, and

,

, where

, are unknown system parameters. The goal of the system parameter identification problem is to identify the system parameter vector

containing the unknown coefficients of the plant transfer function that satisfies

where

and

.

Note that (

67) has the form of (

1) in the frequency domain; however, in most applications the only signals that are available for measurement are the input

, and the output

, and not their derivatives. To address this, we filter (

67) through a stable filter

, where

is an arbitrary monic Hurwitz polynomial of degree

n, to obtain, for

,

where

and

. The time signals

, and

, can be generated by the state equations ([

2])

where, for

,

,

,

, and

and where

.

Theorem 4. Assume that given by (65) has no pole-zero cancellations and . If u is stationary and sufficiently rich of order , then the adaptive laws (20)–(23), (36)–(38), and (55)–(57) guarantee that converges to as . Proof. The proof follows from Theorems 1, 2, and 3 by noting that if

is stationary and sufficiently rich of order

and

G has no pole-zero cancellations, then

is PE [

2] ([Thm. 5.2.4]). □

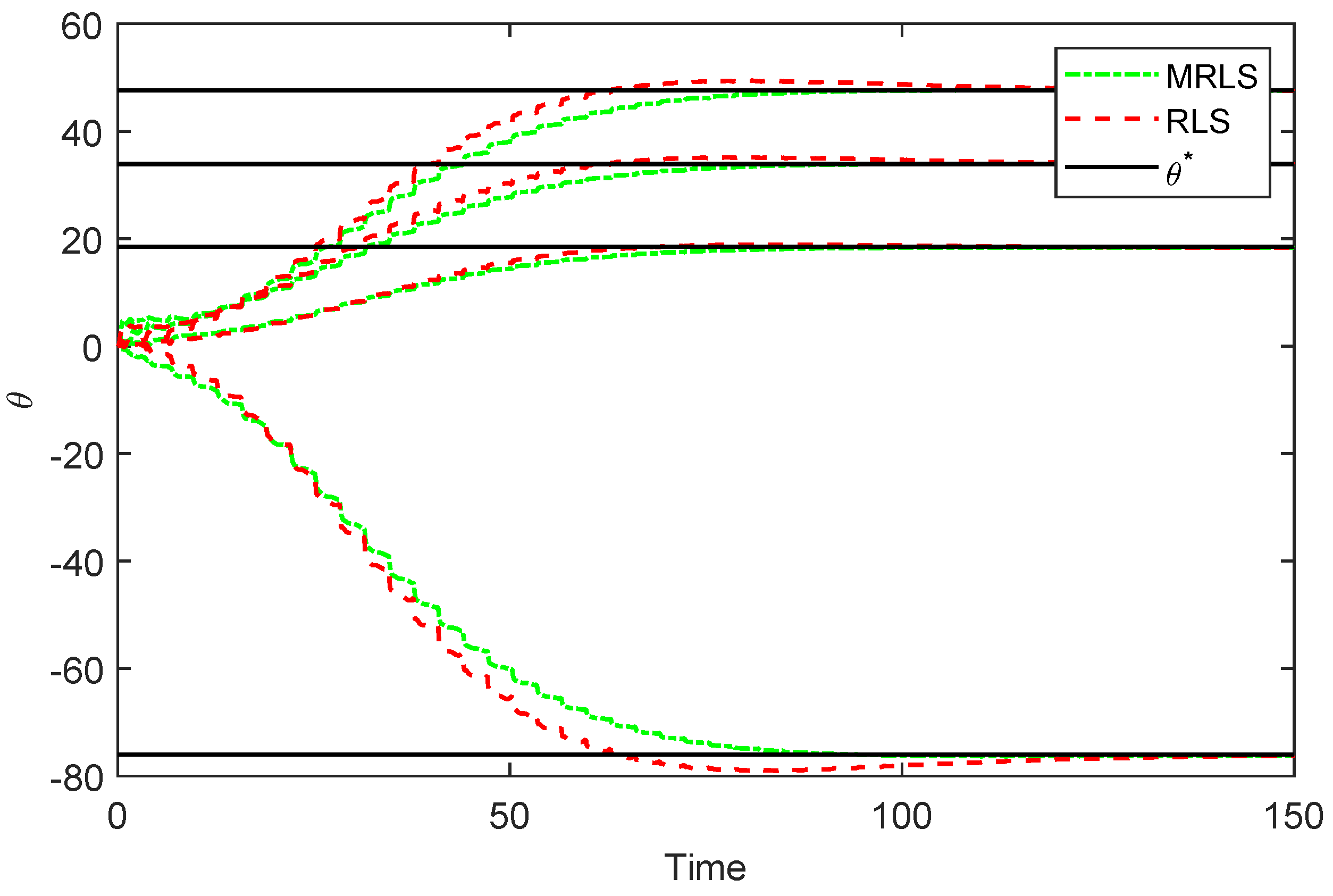

Remark 4. Note that if , then (68) would involve an additional bias error term. As shown in [2], this term converges to the origin exponentially fast, and hence, Theorem 4 remains valid. 4. Momentum-Based Recursive Least Squares and Model Reference Adaptive Control

Recursive least squares type algorithms were first introduced in adaptive control in [

16] and extended in [

2,

17,

18]. In this section, we show how the MRLS algorithm proposed in

Section 2 can be extended to the problem of model reference adaptive control for systems with relative degree one.

Consider the linear SISO system given by

where

,

are unknown polynomials,

is an unknown constant,

is the control system input, and

is the system output. As in [

18], we make the following assumptions.

is minimum phase and has relative degree one.

The degree of is n.

The sign of is known.

The control objective is to design an appropriate control law

, such that all the signals of the closed-loop system are bounded and

, tracks the output

, of a reference model given by

where

,

and

are known constants, and

is the Laplace transform of a bounded piecewise continuous signal

.

To address this problem, consider the filter system ([

2])

where, for

,

,

,

, and

, where

is an arbitrary monic Hurwitz polynomial of degree

. Here, we use

, and

, to form the regressor vector

Note that the existence of a constant parameter vector

such that the transfer function of the SISO system (

76) with

where

,

, matching the reference model transfer function

is guaranteed by the choice of

and Assumptions

–

.

Next, consider the control law

where

,

, and

, and note that the tracking error

satisfies

where

. Note that (

83) has a nonminimal state-space realization given by

where

,

,

, and

. Furthermore, note that

where

,

is a strictly positive real transfer function. In this case, it follows from the Meyer–Kalman–Popov lemma [

2] ([Lem. 3.5.4]) that there exist

positive-definite matrices

and

such that

Since for every nonsingular matrix

and constant

, the realizations

and

,

,

) are equivalent, choosing

and

we can ensure that

is a realization that satisfies (

87) and (88) with

and

is normalized so that

.

Next, consider the recursive least-squares algorithm given by

where

and

,

, and

. Note that for

, (

89) and (90) recover the recursive least-squares algorithm of [

19].

Here, we modify the recursive least-squares algorithm (

89) and (90) to construct our MRLS algorithm as

where

,

,

,

,

and

. Note that (

91) and (92) can be rewritten in terms of the error parameters

, and

as

Theorem 5. Consider the SISO system (76) with control law (82) and the MRLS algorithm given by (91)–(93) with and , where . Then and . If, in addition, , then and . Proof. Consider the function

where

satisfies (

87) and (88), and note that

Next, using the Cauchy–Schwarz and Young inequalities we obtain

Now, using (

98) along with triangle inequality

,

, it follows from (

97) that

which shows that

. Hence,

,

,

. Next, integrating

over

yields

and hence,

. Similarly,

and, since

,

.

Finally, if

, then

satisfies

or

Hence,

, and thus,

. Now, if

, then (85) implies that

and, by Lemma 2,

. □

Remark 5. Note that unlike many MRAC schemes (e.g., [20]), (91)–(93) does not necessitate a projection operator to guarantee boundedness of the tracking error. However, unlike [19], wherein only a lower bound is necessary for , we require knowledge of a lower and upper bound for . Remark 6. It is important to note that there exists an alternative MRAC framework in the litterature known as the normalized adaptive laws [2] whose design is not based on the tracking error but rather on a normalized estimation error of a particular parametrization of the plant. For this framework, the momentum-based integral gradient algorithm (20)–(23), the momentum-based recursive least squares algorithms (36)–(38), and momentum-based composite gradient algorithm (55)–(57) can be used directly for strictly proper plants without a relative degree restriction. In this case, the parametrization of the ideal controller is given by , where satisfies , and .