Electrodynamic Attitude Stabilization of a Spacecraft in an Elliptical Orbit

Abstract

1. Introduction

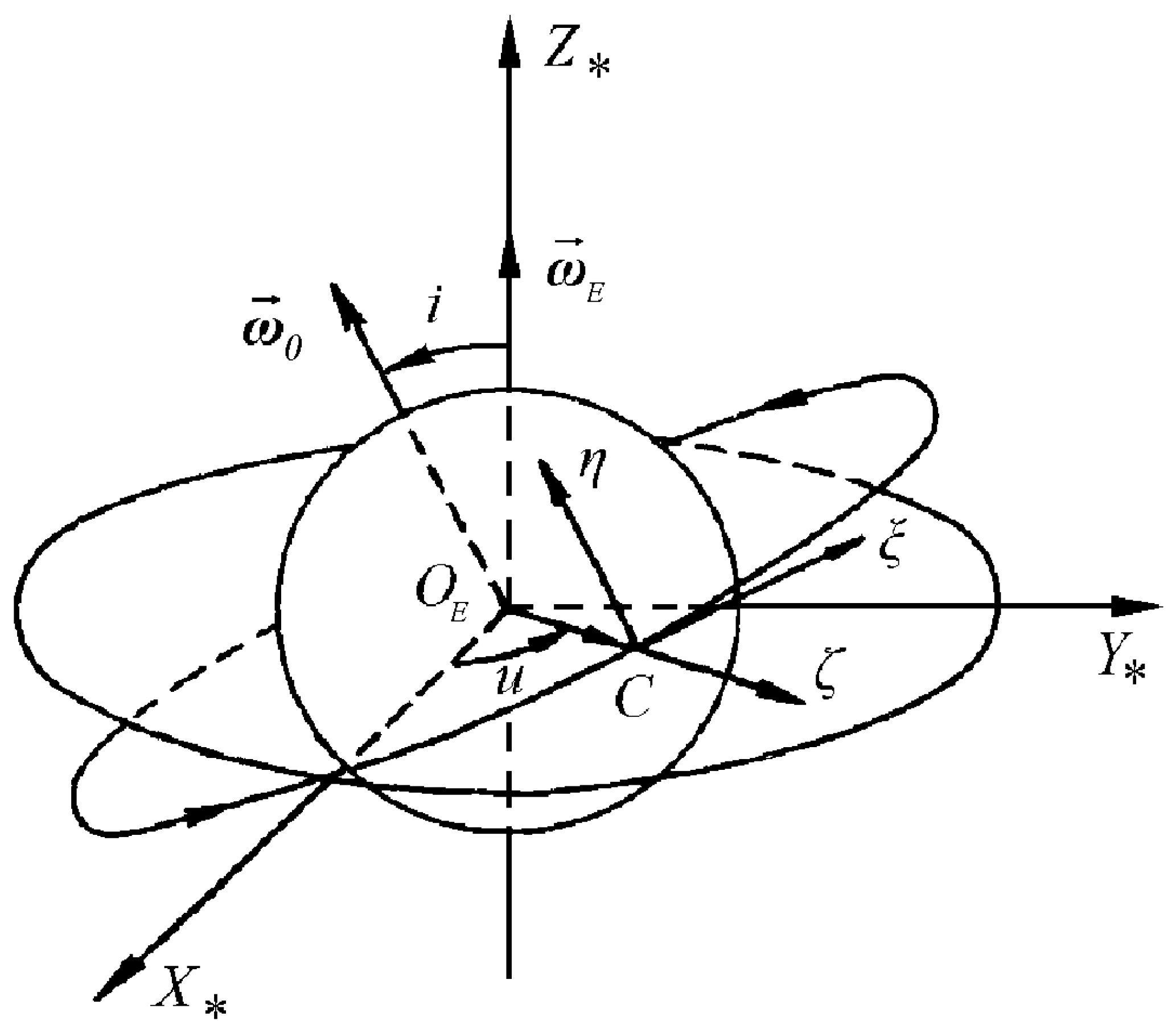

2. Problem Statement

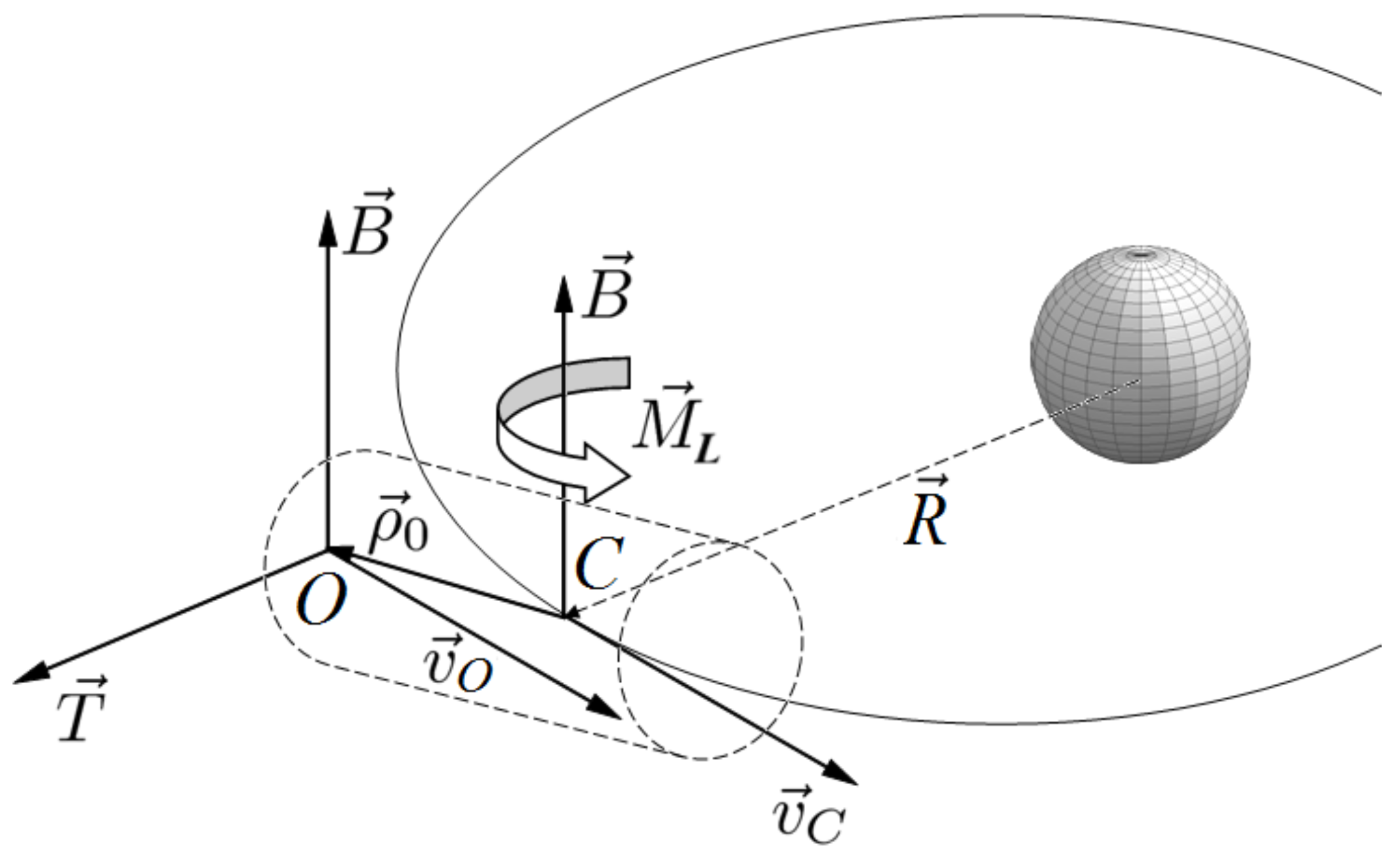

3. Control Torques

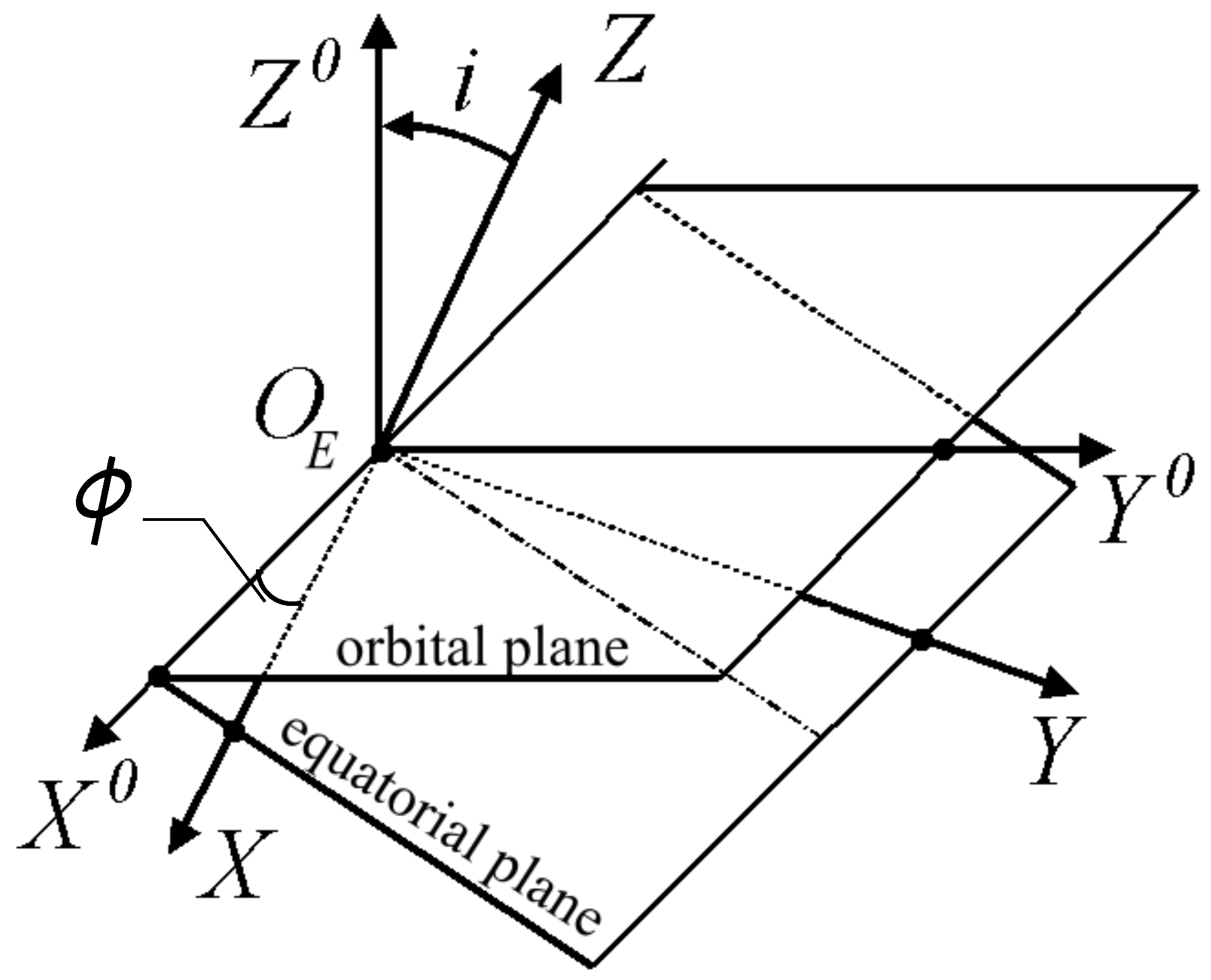

4. The Earth’s Magnetic Field Induction

5. The Disturbing Torque

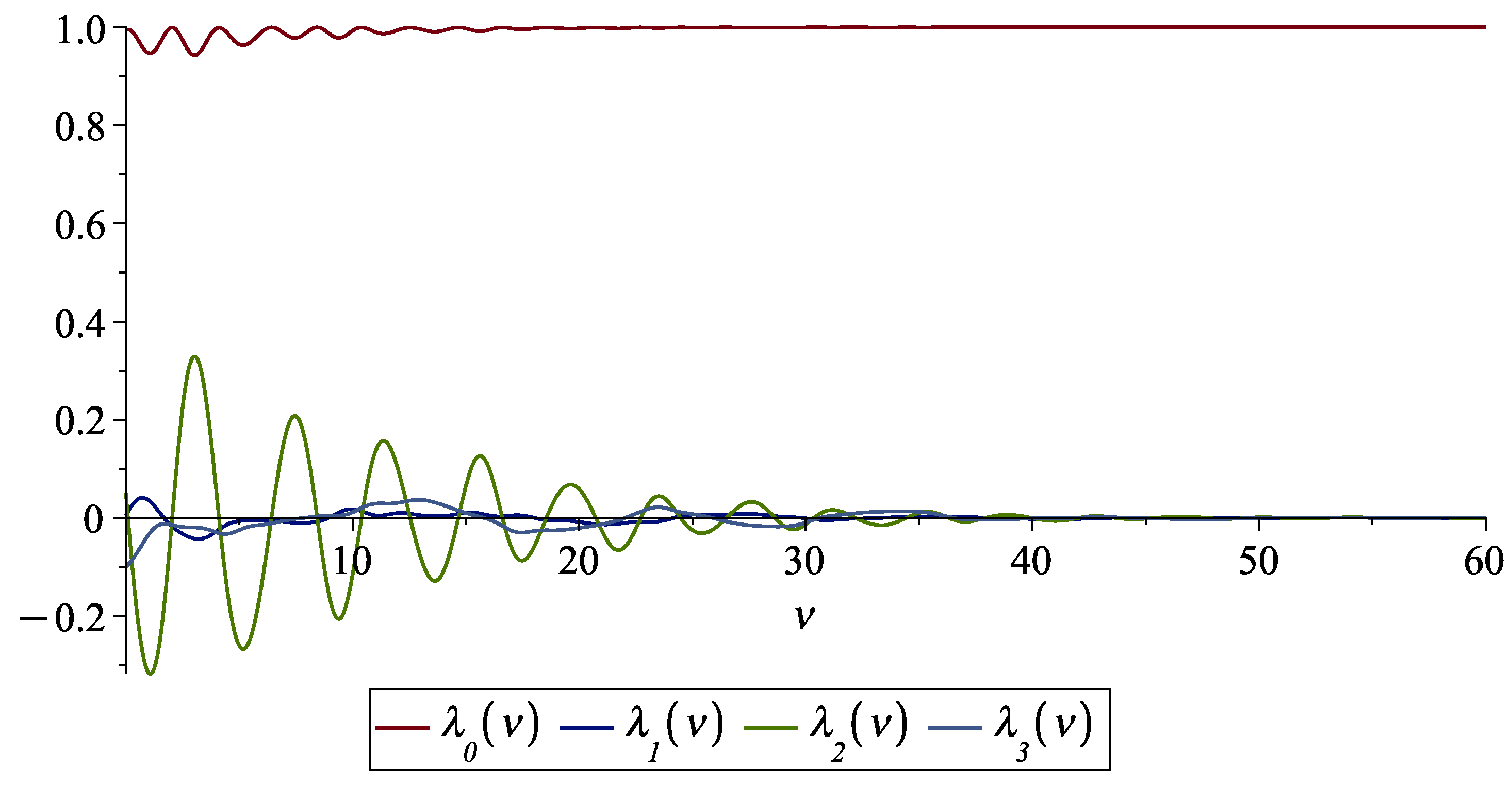

6. Compensation of the Disturbing Torque

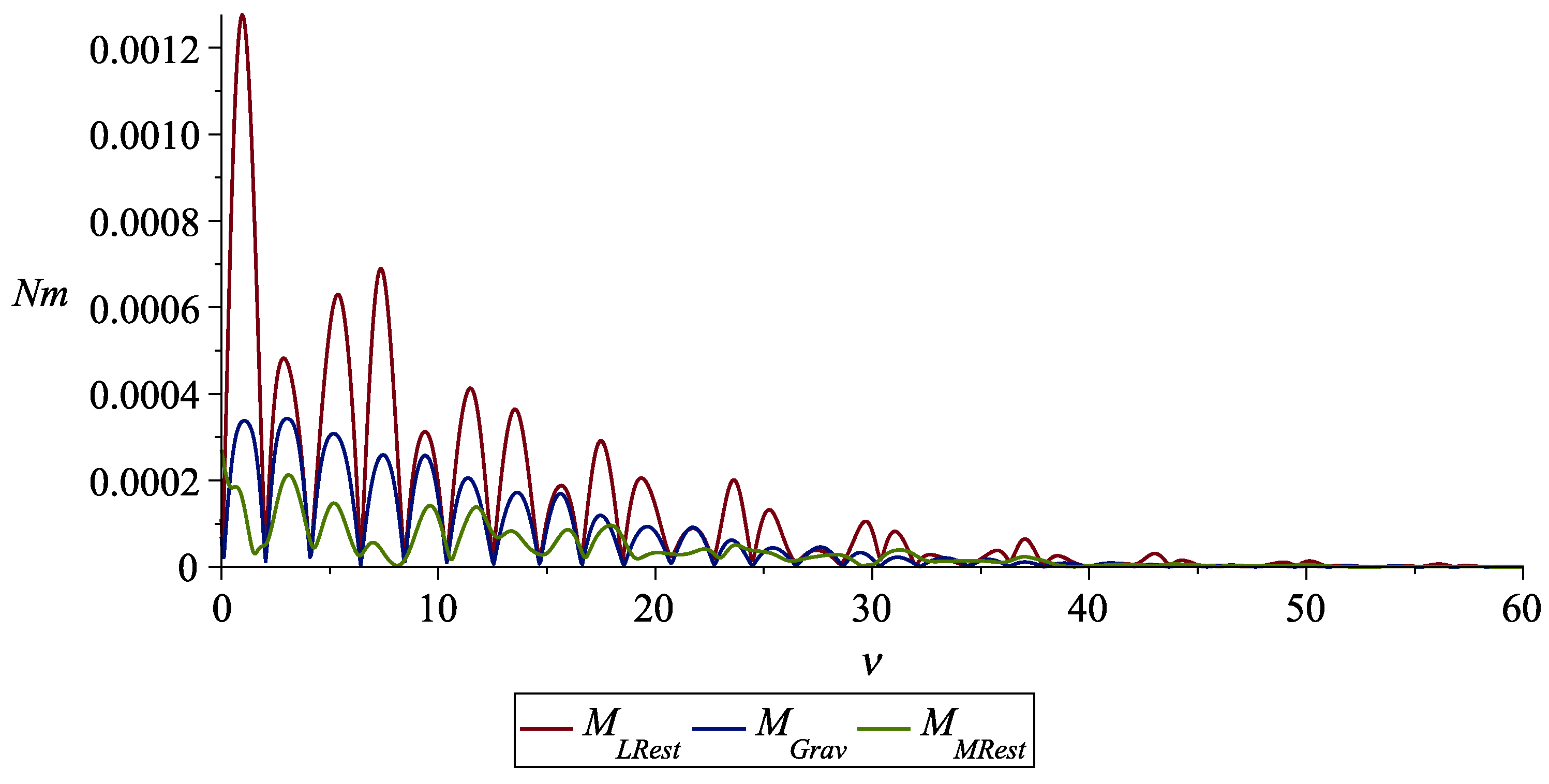

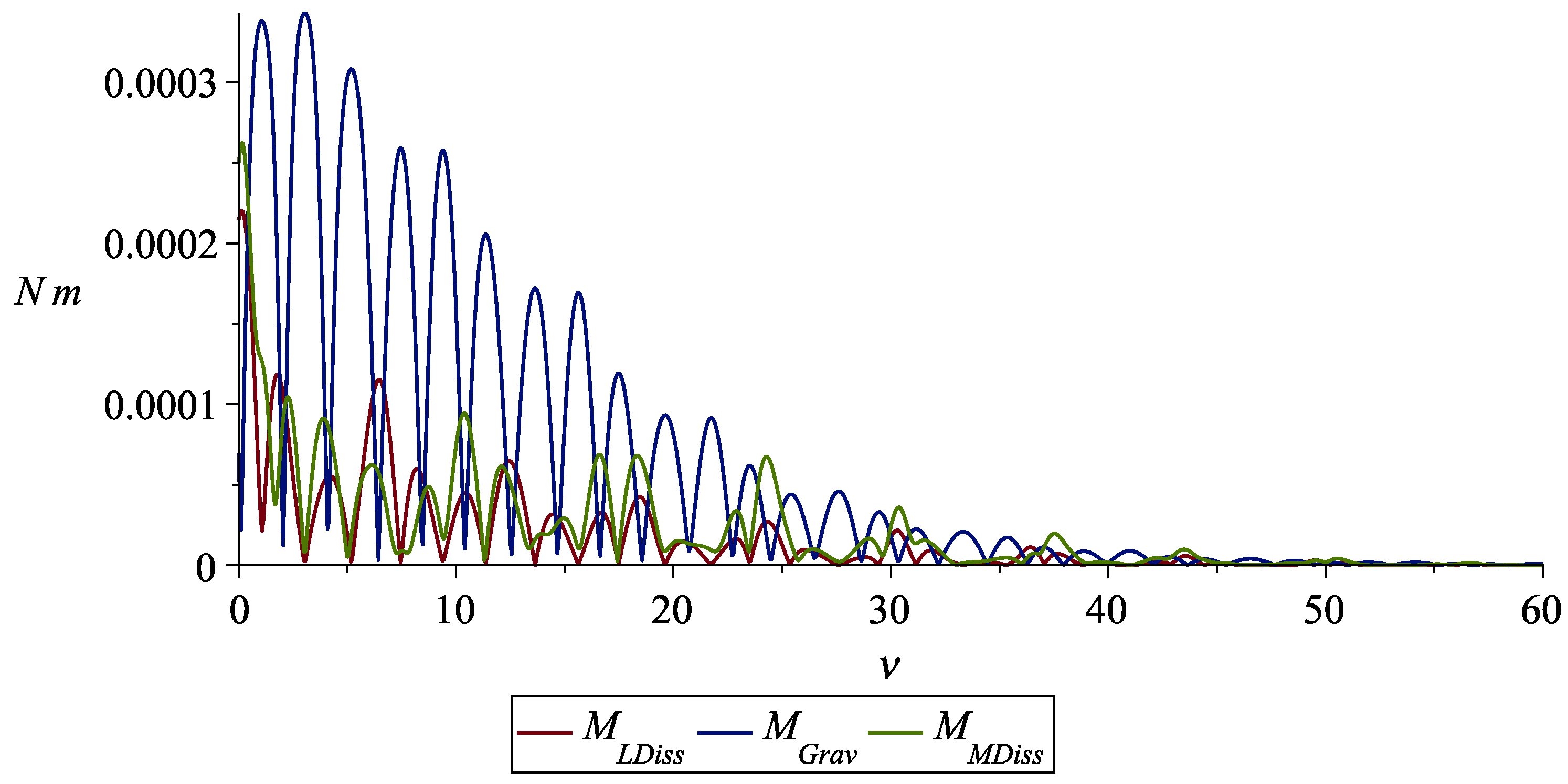

7. Computer Modeling and Numerical Integration Results

- orbit parameters: eccentricity , orbital inclination , focal parameter ;

- spacecraft parameters: moments of inertia , , , total charge C;

- control parameters: , , , ;

- initial deviation: ;

- initial angular velocity components: .

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silani, E.; Lovera, M. Magnetic spacecraft attitude control: A survey and some new results. Control Eng. Pract. 2005, 13, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sinha, M.; Kumar, K.; Misra, A. Reconfigurable magnetic attitude control of Earth-pointing satellites. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G-J. Aerosp. Eng. 2010, 224, 1309–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sinha, M.; Misra, A. Dynamic Neural Units for Adaptive Magnetic Attitude Control of a Satellite. In Proceedings of the AIAA/AAS Astrodynamics Specialist Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–5 August 2010; Volume 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.; Ovchinnikov, M.; Penkov, V.; Roldugin, D.; Doronin, D.; Ovchinnikov, A. Advanced numerical study of the three-axis magnetic attitude control and determination with uncertainties. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 132, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofyali, A.; Jafarov, E.M.; Wisniewski, R. Robust and global attitude stabilization of magnetically actuated spacecraft through sliding mode. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 76, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, V.M.; Kalenova, V.I. Satellite Control Using Magnetic Moments: Controllability and Stabilization Algorithms. Cosm. Res. 2020, 58, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Kolmanovsky, I.; Yoshimura, Y.; Bando, M.; Nagasaki, S.; Hanada, T. Nonlinear Model Predictive Detumbling of Small Satellites with a Single-Axis Magnetorquer. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2021, 44, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.A. A method of semipassive attitude stabilization of a spacecraft in the geomagnetic field. Cosm. Res. 2003, 41, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, H.; Hachiyama, S.; Bando, M. Attitude dynamics of a pendulum-shaped charged satellite. Acta Astronaut. 2012, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, Y.A.; Shoaib, M. Attitude dynamics and control of spacecraft using geomagnetic Lorentz force. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2015, 15, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, D.K.; Sinha, M.; Kumar, K.D. Fault-tolerant attitude control of magneto-Coulombic satellites. Acta Astronaut. 2015, 116, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, D.K.; Sinha, M. Three-axis attitude control of Earth-pointing isoinertial magneto-Coulombic satellites. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2017, 5, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, A.; Tikhonov, A. Averaging technique in the problem of Lorentz attitude stabilization of an Earth-pointing satellite. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipov, K.A.; Tikhonov, A.A. Parametric control in the problem of spacecraft stabilization in the geomagnetic field. Autom. Remote Control 2007, 68, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.A.; Spasic, D.T.; Antipov, K.A.; Sablina, M.V. Optimizing the electrodynamical stabilization method for a man-made Earth satellite. Autom. Remote Control 2011, 72, 1898–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipov, K.A.; Tikhonov, A.A. Electrodynamic Control for Spacecraft Attitude Stability in the Geomagnetic Field. Cosm. Res. 2014, 52, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, A.Y.; Aleksandrova, E.B.; Tikhonov, A.A. Stabilization of a programmed rotation mode for a satellite with electrodynamic attitude control system. Adv. Space Res. 2018, 62, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenova, V.I.; Morozov, V.M. Stabilization of Satellite Relative Equilibrium Using Magnetic and Lorentzian Moments. Cosm. Res. 2021, 59, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, A.Y.; Tikhonov, A.A. Natural Magneto-velocity Coordinate System for Satellite Attitude Stabilization: Dynamics and Stability Analysis. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2023, 9, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailabouni, D.; Meister, A.; Spindler, K. Attitude maneuvers avoiding forbidden directions. Astrodynamics 2023, 7, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, T.; Wen, H.; Jin, D. Analytical libration control law for electrodynamic tether system with current constraint. Astrodynamics 2024, 8, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigehara, M. Geomagnetic Attitude Control of an Axisymmetric Spinning Satellite. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 1972, 9, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, Y.; Shoaib, M. Attitude stabilization of a charged spacecraft subject to Lorentz force. Proceeding of the 2nd IAA Dynamics and Control of Space System, Rome, Italy, 24–26 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Aziz, Y.; Shoaib, M. Periodic solutions for rotational motion of an axially symmetric charged satellite. Appl. Math. Sci. 2015, 9, 1551–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oland, E. Modeling and Attitude Control of Satellites in Elliptical Orbits. In Applied Modern Control; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, X. Spacecraft fast fly-around formations design using the parallelogram configuration. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.A. Refinement of the Oblique Dipole Model in the Evolution of Rotary Motion of a Charged Body in the Geomagnetic Field. Cosm. Res. 2002, 40, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.A.; Petrov, K.G. Multipole models of the Earth’s magnetic field. Cosm. Res. 2002, 40, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipov, K.A.; Tikhonov, A.A. Multipole Models of the Geomagnetic Field: Construction of the Nth Approximation. Geomagn. Aeron. 2013, 53, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alken, P.; Thébault, E.; Beggan, C.D.; Amit, H.; Aubert, J.; Baerenzung, J.; Bondar, T.N.; Brown, W.J.; Califf, S.; Chambodut, A.; et al. International Geomagnetic Reference Field: The thirteenth generation. Earth Planets Space 2021, 73, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beletsky, V.V. Motion of an Artificial Satellite About Its Center of Mass; Israel Program for Scientific Translation; NASA: Jerusalem, Israel, 1966. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klyushin, M.A.; Maksimenko, M.V.; Tikhonov, A.A. Electrodynamic Attitude Stabilization of a Spacecraft in an Elliptical Orbit. Aerospace 2024, 11, 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11110956

Klyushin MA, Maksimenko MV, Tikhonov AA. Electrodynamic Attitude Stabilization of a Spacecraft in an Elliptical Orbit. Aerospace. 2024; 11(11):956. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11110956

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlyushin, Maksim A., Margarita V. Maksimenko, and Alexey A. Tikhonov. 2024. "Electrodynamic Attitude Stabilization of a Spacecraft in an Elliptical Orbit" Aerospace 11, no. 11: 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11110956

APA StyleKlyushin, M. A., Maksimenko, M. V., & Tikhonov, A. A. (2024). Electrodynamic Attitude Stabilization of a Spacecraft in an Elliptical Orbit. Aerospace, 11(11), 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11110956