Abstract

This article proposes a visual inertial navigation algorithm intended to diminish the horizontal position drift experienced by autonomous fixed-wing UAVs (unmanned air vehicles) in the absence of GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) signals. In addition to accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers, the proposed navigation filter relies on the accurate incremental displacement outputs generated by a VO (visual odometry) system, denoted here as a virtual vision sensor, or VVS, which relies on images of the Earth surface taken by an onboard camera and is itself assisted by filter inertial estimations. Although not a full replacement for a GNSS receiver since its position observations are relative instead of absolute, the proposed system enables major reductions in the GNSS-denied attitude and position estimation errors. The filter is implemented in the manifold of rigid body rotations or in order to minimize the accumulation of errors in the absence of absolute observations. Stochastic high-fidelity simulations of two representative scenarios involving the loss of GNSS signals are employed to evaluate the results. The authors release the C++ implementation of both the visual inertial navigation filter and the high-fidelity simulation as open-source software.

1. Introduction and Outline

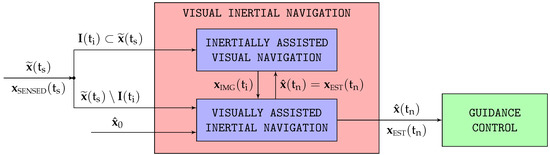

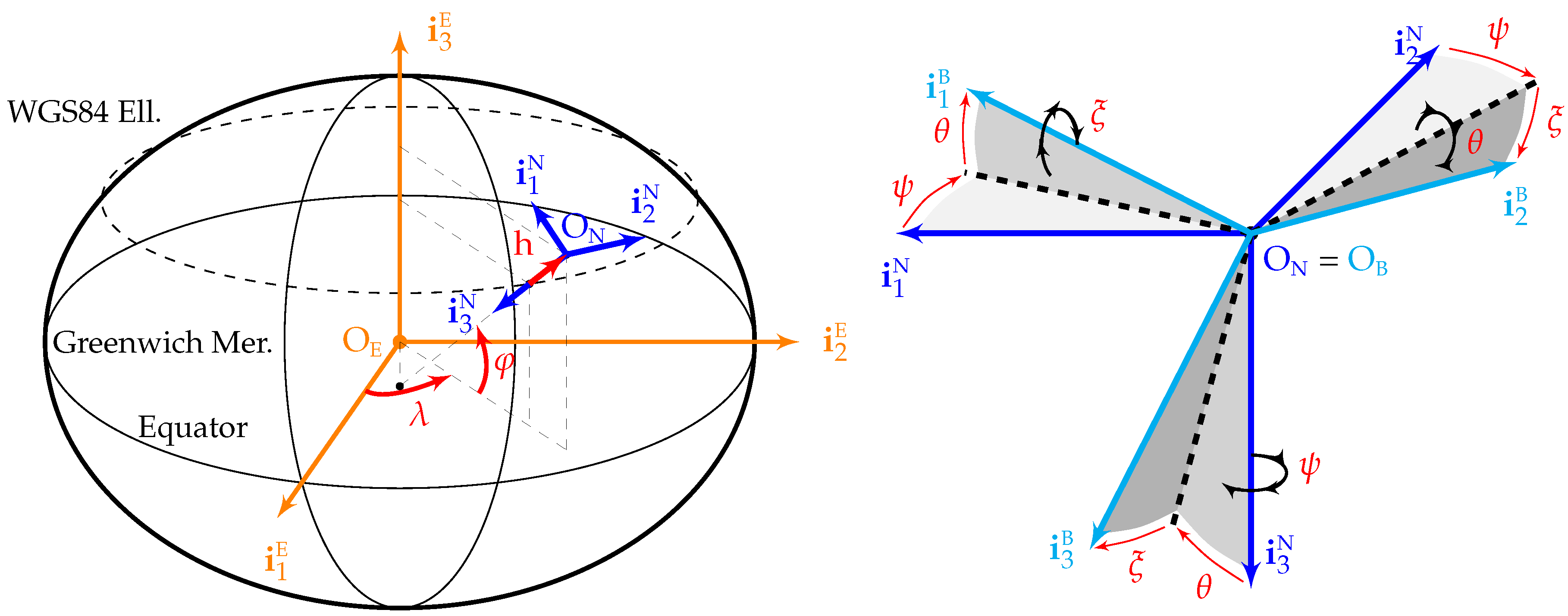

The main objective of this article is to develop a navigation system capable of diminishing the position drift inherent to the flight in GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System)-denied conditions of an autonomous fixed-wing aircraft, so in case GNSS signals become unavailable during flight, the vehicle has a higher probability of reaching the vicinity of a distant recovery point, from where it can be landed by remote control. The proposed approach combines two different navigation systems (inertial, which is based on the outputs of all onboard sensors except the camera, and visual, which relies exclusively on the images of the Earth surface taken from the aircraft) in such a way that both simultaneously assist and control each other, resulting in a positive feedback loop with major improvements in horizontal position estimation accuracy compared with either system by itself.

The fusion between the inertial and visual systems is a two-step process. The first one, described in [1], feeds the visual system with the inertial attitude and altitude estimations to assist with its nonlinear pose optimizations, resulting in major horizontal position accuracy gains with respect to both a purely visual system (without inertial assistance) and a standalone inertial one such as that described in [2]. The second step, which is the focus of this article, feeds back the visual horizontal position estimations into the inertial navigation filter as if they were the outputs of a virtual vision sensor, or VVS, replacing those of the GNSS receiver, and results in additional horizontal position accuracy improvements.

Section 2 describes the mathematical notation employed throughout the article. An introduction to GNSS-denied navigation and its challenges, together with a review of the state of the art in visual inertial navigation, is included in Section 3. Section 4 and Section 5 discuss the article novelty and main applications, respectively. The proposed architecture to combine the inertial and visual navigation algorithms is discussed in Section 6, which relies on the VVS described in Section 7. The VVS outputs are employed by the navigation filter, which is described in detail in Section 8. Section 9 introduces the stochastic high-fidelity simulation employed to evaluate the navigation results by means of Monte Carlo executions of two scenarios representative of the challenges of GNSS-denied navigation. The results obtained when applying the proposed algorithms to these scenarios are described in Section 10, comparing them with those achieved by standalone inertial and visual systems. Last, Section 11 summarizes the results, while Appendix A describes the obtainment of various Jacobians employed in the proposed navigation filter.

2. Mathematical Notation

The meaning of all variables is specified on their first appearance. Any variable with a hat accent refers to its estimated value, with a tilde to its measured value, and with a dot to its time derivative. In the case of vectors, which are displayed in bold (e.g., ), other employed symbols include the skew-symmetric form and the double vertical bars , which refer to the norm. The superindex T denotes the transpose of a vector or matrix. In the case of scalars, the vertical bars refer to the absolute value. The left arrow represents an update operation, in which the value on the right of the arrow is assigned to the variable on the left.

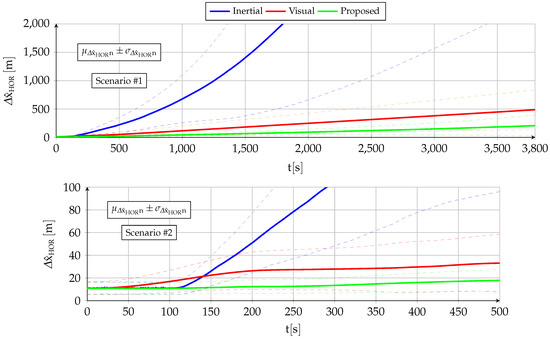

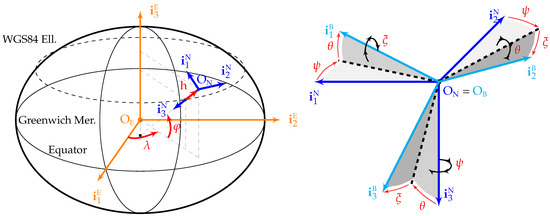

Four different reference frames are employed in this article: the ECEF (Earth centered Earth fixed) frame (centered at the Earth center of mass , with pointing towards the geodetic north along the Earth rotation axis, contained in both the equator and zero longitude planes, and orthogonal to and forming a right-handed system), the NED (north east down) frame (centered at the aircraft center of mass , with axes aligned with the geodetic north, east, and down directions), the body frame (centered at the aircraft center of mass , with contained in the plane of symmetry of the aircraft pointing forward along a fixed direction, contained in the plane of symmetry of the aircraft, normal to and pointing downward, and orthogonal to both in such a way that they form a right-hand system), and the inertial frame (centered at the Earth center of mass with axes that do not rotate with respect to any stars other than the Sun). The first three frames are graphically depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

ECEF (), NED (), and body () reference frames.

This article makes use of the space of rigid body rotations and, hence, relies on the Lie algebra of the special orthogonal group of , known as ; refs. [3,4,5] are recommended as references. Generic rotations are represented by and usually parameterized by the unit quaternion , although the direct cosine matrix is also employed as required; tangent space representations include the rotation vector and the angular velocity . Related symbols include the quaternion conjugate , the quaternion product , and the plus and minus operators.

Superindexes are employed over vectors to specify the frame in which they are viewed (e.g., refers to ground velocity viewed in , while is the same vector but viewed in ). Subindexes may be employed to clarify the meaning of a variable or vector, but may also indicate a given vector component; e.g., refers to the second component of . In addition, where two reference frames appear as subindexes to a vector, it means that the vector goes from the first frame to the second. For example, refers to the angular velocity from to viewed in . Jacobians are represented by a combined with a subindex and a superindex; the former identifies the function domain, while the latter applies to the function image or codomain.

4. Novelty

The main novelty of this article (second phase of the fusion between the inertial and visual navigation systems) lies in the following two topics:

- The use of a modified EKF scheme within the navigation filter (Section 8) based on Lie algebra to ensure that the estimated aircraft body attitude is propagated along its tangent space and never deviates from its manifold, reducing the error growth inherent to concatenating estimations over a long period of time.

- The transformation within the VVS (Section 7) of the position estimations obtained by the visual system into incremental displacement measurements, which are unbiased and hence more adequate to be used as observations within an EKF.

When comparing the integrated system (which includes both [1] and this article) with the state of the art discussed in Section 3, the proposed approach combines the high accuracy representative of tightly coupled smoothers with the lack of complexity and reduced computing requirements of filters and loosely coupled systems. The existence of two independent solutions (inertial and visual) hints to a loosely coupled approach, but in fact, the proposed solution shares most traits with tightly coupled pipelines:

- No information is discarded because the two solutions are not independent, as each simultaneously feeds and is fed by the other. The visual estimations depend on the inertial outputs, while the inertial filter uses the visual incremental displacement estimations as observations. Unlike loosely coupled solutions, the visual estimations for attitude and altitude are not allowed to deviate from the inertial ones above a certain threshold, so they do not drift.

- The two estimations are never fused together, as the inertial solution constitutes the final output, while the sole role of the visual outputs is to act as the previously mentioned incremental sensor.

With respect to the last criterion found in Section 3, the proposed approach contains both a filter within the inertial system and a keyframe-based sliding window smoother within the visual one, obtaining the best properties of both categories.

5. Application

The visual inertial solutions listed in Section 3 are quite generic with respect to the platforms on which they are mounted, with most applications focused on the short distance trajectories of ground vehicles, indoor robots, and multirotors, as well as with respect to the employed sensors, which are usually restricted to the IMU and one or more cameras. The proposed approach differs in its more restricted application, as it focuses on the specific case of long-distance GNSS-denied turbulent flight of fixed-wing autonomous aircraft:

- Being restricted to aerial vehicles, it takes advantage of the extra sensors already present on board these platforms, such as magnetometers and barometer.

- The fixed-wing limitation is caused by the visual system relying on the pitot tube to continue navigating when overflying texture-poor terrain [1].

- As exemplified by the two scenarios employed to evaluate the algorithms, the proposed approach can cope with heavy turbulence, which increases the platform accelerations as well as the optical flow between consecutive images. Although not discussed in the results, the turbulence level has a negligible effect on the navigation accuracy as long as it remains below a sufficiently elevated threshold.

- With the exception of atmospheric pressure changes, which accumulate as vertical position estimation errors (Section 10.2), weather changes such as wind and atmospheric temperature have no effect on the navigation accuracy.

- It focuses more on GNSS-denied environments of a different nature than those experienced by other platforms, as it can always be assumed that GNSS signals are present at the beginning of the flight, and if they disappear, the reason is likely to be technical error or intentional action, so the vehicle needs to be capable of flying for long periods of time in GNSS-denied conditions.

- The reliance on visual navigation imposes certain restrictions, such as the need for sufficient illumination, lack of cloud cover below the aircraft, and impossibility to navigate over large bodies of water. The use of infrared cameras, although out of the scope of this article, is a promising research area for the first two restrictions, but the lack of static features makes visual systems inadequate for navigation over water.

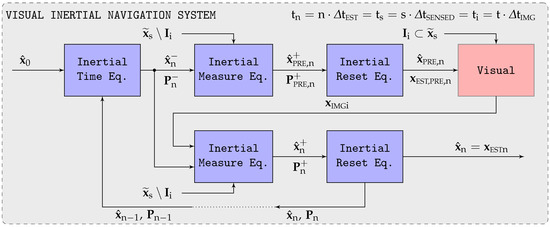

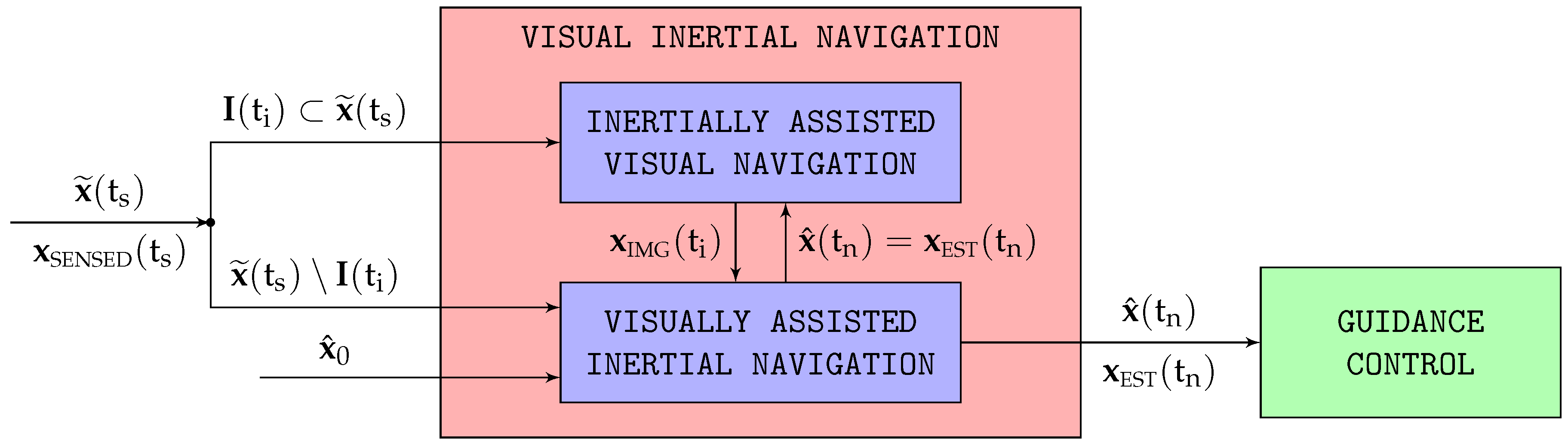

7. Virtual Vision Sensor

The virtual vision sensor (VVS) constitutes an alternative denomination for the incremental displacement outputs obtained by the inertial assisted visual system described in [1]. Its horizontal position estimations drift with time due to the absence of absolute observations, but when evaluated on an incremental basis, that is, from one image to the next, the incremental displacement estimations are quite accurate. This section shows how to convert these incremental estimations into measurements for the geodetic coordinates () and the ground velocity (), so the VVS can smoothly replace the GNSS receiver within the navigation filter in the absence of GNSS signals (Section 8).

Their obtainment relies on the current visual state generated by the visual system, the one obtained with the previous frame , as well as the estimated state = = corresponding to the previous image generated by the inertial system. Note that as = = , the relationship between i and n is as follows, where is the number of inertial executions for every image being processed (Table 1):

- To obtain the VVS velocity observations (), it is necessary to first compute the geodetic coordinate (longitude , latitude , altitude h) time derivative based on the difference between their values corresponding to the last two images (2), followed by their transformation into per (3), in which M and N represent the WGS84 radii of curvature of meridian and prime vertical, respectively. Note that is very noisy given how it is obtained.

- With respect to the VVS geodetic coordinates, the sensed longitude and latitude can be obtained per (5) and (6) based on propagating the previous inertial estimations (those corresponding to the time of the previous VVS reading) with their visually obtained time derivatives. To avoid drift, the geometric altitude is estimated based on the barometer observations assuming that the atmospheric pressure offset remains frozen from the time the GNSS signals are lost [2].

With respect to the covariances, the authors have assigned the VVS an ad hoc position standard deviation one order of magnitude lower than that employed for the GNSS receiver so the navigation filter (Section 8) closely tracks the position observations provided by the VVS. Given the noisy nature of the virtual velocity observations, the authors have preferred to employ a dynamic evaluation for the velocity standard deviation, which coincides with the absolute value (for each of the three dimensions) of the difference between each new velocity observation and the running average of the last 20 readings (equivalent to the last ). In this way, when GNSS signals are available, the covariance of the position observations is higher, so the navigation filter slowly corrects the position estimations obtained from integrating the state equations instead of closely adhering to the noisy GNSS position measurements; when GNSS signals are not present, the VVS low position observation covariance combined with the high-velocity one implies that the navigation EKF (Section 8) closely tracks the VVS position readings (4), continuously adjusting the aircraft velocity estimations with little influence from the VVS velocity observations in order to complement its position estimations.

9. Testing: High-Fidelity Simulation and Scenarios

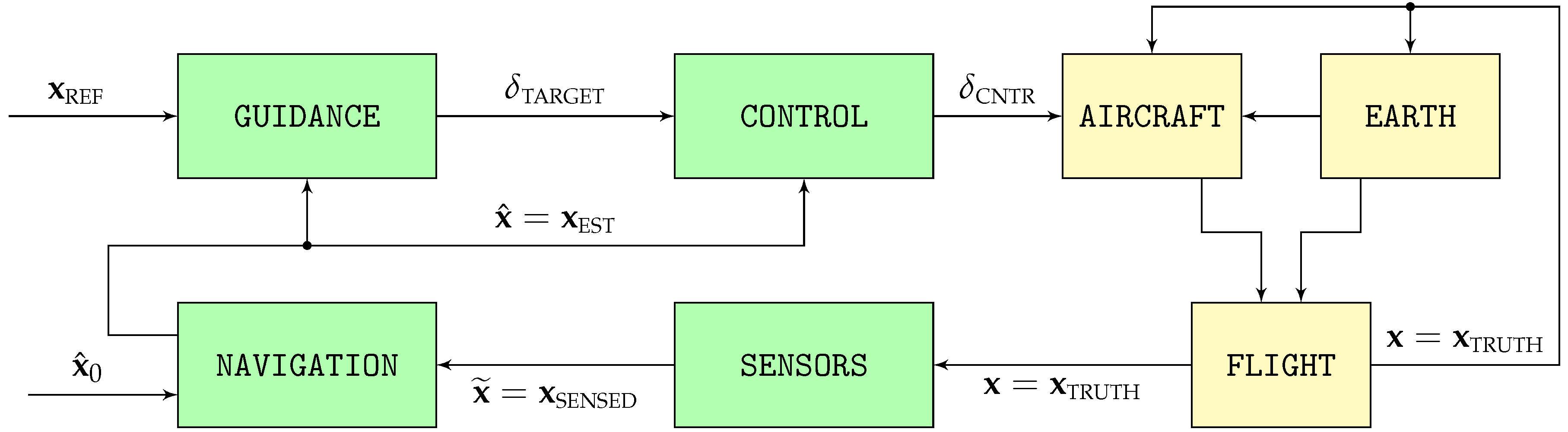

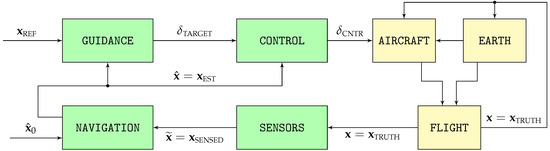

To evaluate the performance of the proposed navigation algorithms, this article relies on Monte Carlo simulations consisting of one hundred runs each of two different scenarios based on the high-fidelity stochastic flight simulator graphically depicted in Figure 4. The simulator, whose open source C++ implementation is available in [80], models the flight of a fixed-wing piston engine autonomous UAV.

Figure 4.

Components of the high-fidelity simulation.

The simulator consists of two distinct processes:

- The first, represented by the yellow blocks on the right of Figure 4, models the physics of flight and the interaction between the aircraft and its surroundings, which results in the real aircraft trajectory .

- The second, represented by the green blocks on the left, contains the aircraft systems in charge of ensuring that the resulting trajectory adheres as much as possible to the mission objectives. It includes the different sensors whose output comprises the sensed trajectory , the navigation system in charge of filtering it to obtain the estimated trajectory , the guidance system that converts the reference objectives into the control targets , and the control system that adjusts the position of the throttle and aerodynamic control surfaces so the estimated trajectory is as close as possible to the reference objectives . Table 1 lists the working frequencies of the various blocks represented in Figure 4.

All components of the flight simulator have been modeled with as few simplifications as much as possible to increase the realism of the results. With the exception of the aircraft performances and its control system, which are deterministic, all other simulator components are treated as stochastic and hence vary from one execution to the next, enhancing the significance of the Monte Carlo simulation results.

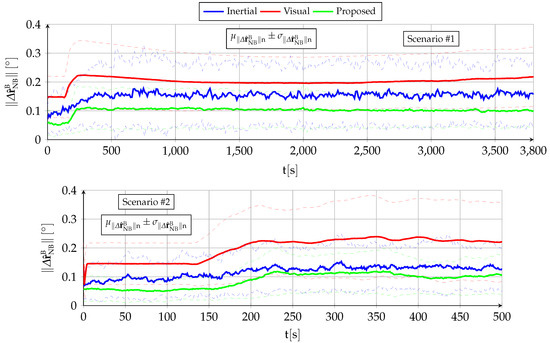

Most VIO packages discussed in Section 3 include in their release articles an evaluation when applied to the EuRoC MAV data sets [64], and so do independent evaluations, such as [65]. These data sets contain perfectly synchronized stereo images, IMU measurements, and ground truth readings obtained with laser, for eleven different indoor trajectories flown with a MAV, each with a duration in the order of 2 min and a total distance in the order of . This fact by itself indicates that the target application of exiting VIO implementations differs significantly from the main focus of this article, as there may exist accumulating errors that are completely nondiscernible after such short periods of time, but that grow nonlinearly and have the capability of inducing significant pose errors when the aircraft remains aloft for long periods of time. The algorithms presented in this article are hence tested through simulation under two different scenarios designed to analyze the consequences of losing the GNSS signals for long periods of time; these two scenarios coincide with those employed in [1,2] to evaluate standalone visual and inertial algorithms. Most parameters comprising the scenarios are defined stochastically, resulting in different values for every execution. Note that all results shown in Section 10 are based on Monte Carlo simulations comprising one hundred runs of each scenario, testing the sensitivity of the proposed navigation algorithms to a wide variety of values in the parameters.

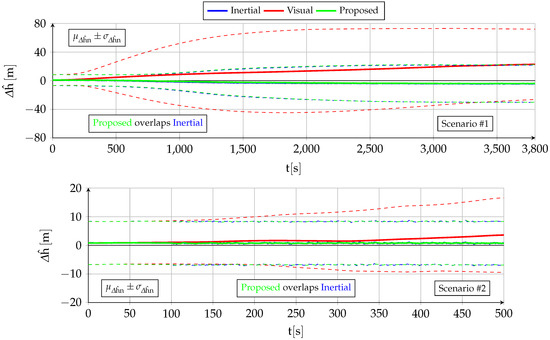

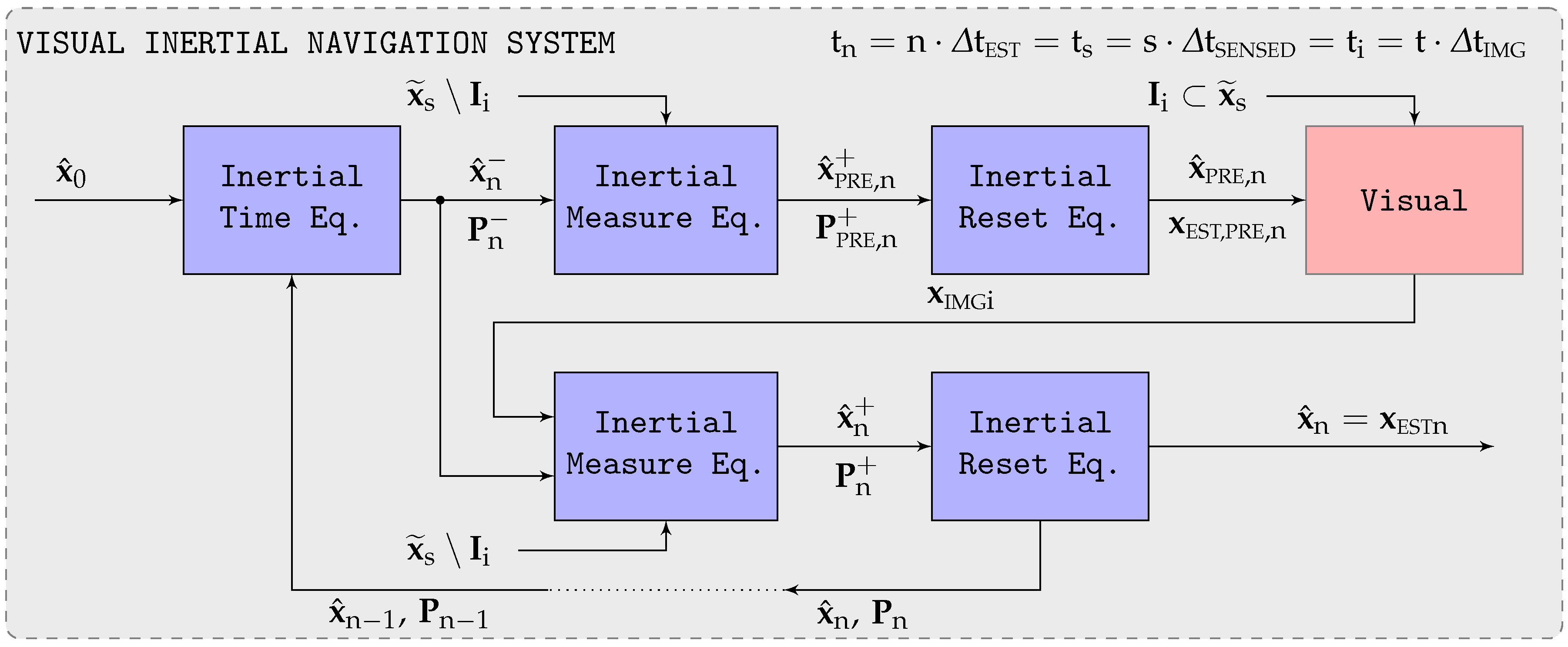

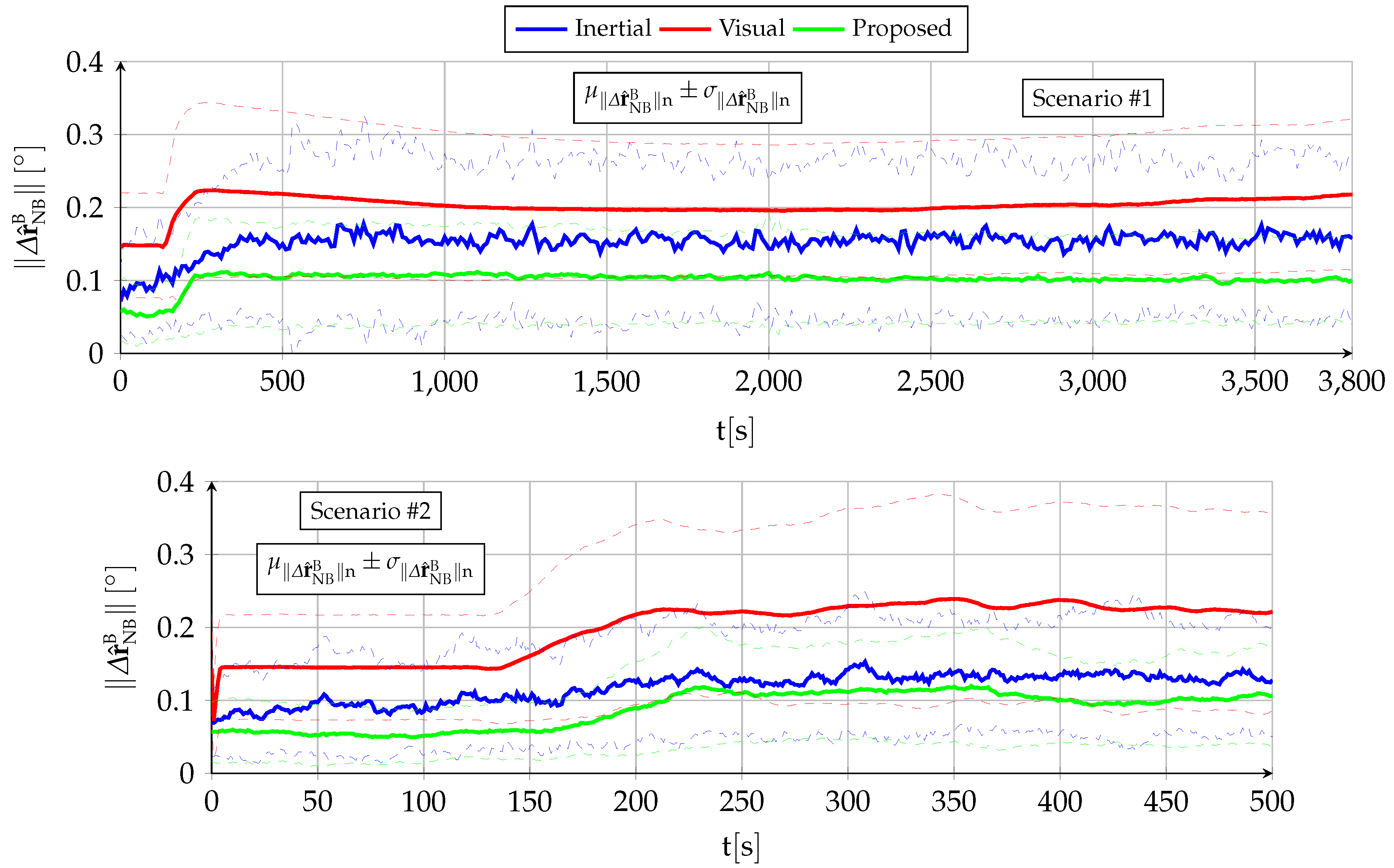

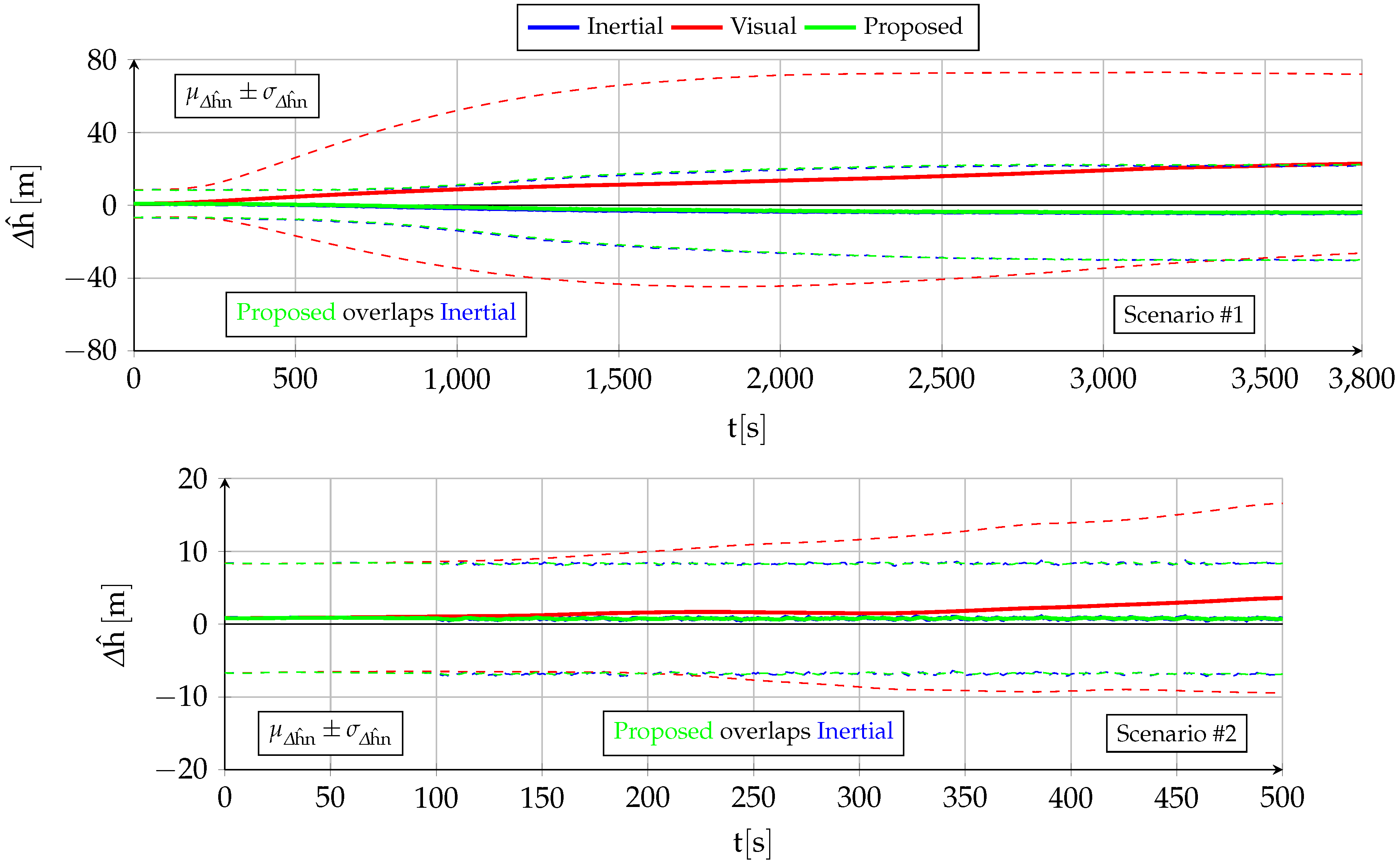

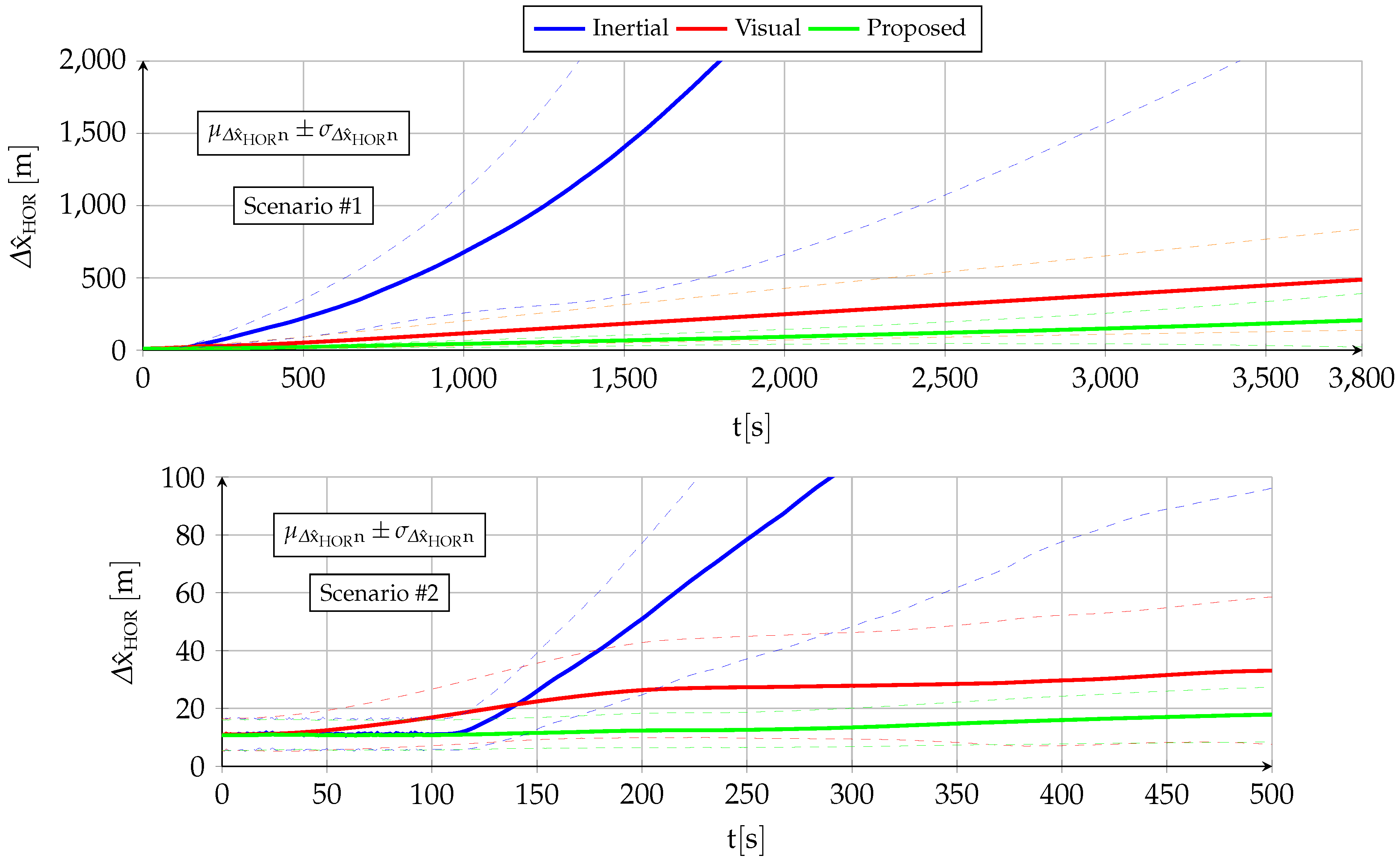

- Scenario #1 has been defined with the objective of adequately representing the challenges faced by an autonomous fixed-wing UAV that suddenly cannot rely on GNSS and hence changes course to reach a predefined recovery location situated at approximately 1 h of flight time. In the process, in addition to executing an altitude and airspeed adjustment, the autonomous aircraft faces significant weather and wind field changes that make its GNSS-denied navigation even more challenging.With respect to the mission, the stochastic parameters include the initial airspeed, pressure altitude, and bearing (); their final values (); and the time at which each of the three maneuvers is initiated (turns are executed with a bank angle of . Altitude changes employ an aerodynamic path angle of . Additionally, airspeed modifications are automatically executed by the control system as set-point changes). The scenario lasts for , while the GNSS signals are lost at .The wind field is also defined stochastically, as its two parameters (speed and bearing) are constant both at the beginning () and conclusion () of the scenario, with a linear transition in between. The specific times at which the wind change starts and concludes also vary stochastically among the different simulation runs.A similar linear transition occurs with the temperature and pressure offsets that define the atmospheric properties, as they are constant both at the start () and end () of the flight.The turbulence remains strong throughout the whole scenario, but its specific values also vary stochastically from one execution to the next.

- Scenario #2 represents the challenges involved in continuing with the original mission upon the loss of the GNSS signals, executing a series of continuous turn maneuvers over a relatively short period of time with no atmospheric or wind variations. As in scenario , the GNSS signals are lost at , but the scenario duration is shorter (). The initial airspeed and pressure altitude () are defined stochastically and do not change throughout the whole scenario; the bearing, however, changes a total of eight times between its initial and final values, with all intermediate bearing values as well as the time for each turn varying stochastically from one execution to the next. Although the same turbulence is employed as in scenario , the wind and atmospheric parameters () remain constant throughout scenario .

11. Summary and Conclusions

This article proves that the inertial and visual navigation systems of an autonomous UAV can be combined in such a way that the resulting long-term GNSS-denied horizontal position drift is only a small fraction of what can be achieved by either system individually. The proposed system, however, does not a constitute a full GNSS replacement as it relies on incremental instead of absolute position observations and, hence, can only reduce the position drift but not eliminate it.

The proposed visual inertial navigation filter, specifically designed for the challenges faced by autonomous fixed-wing aircraft that encounter GNSS-denied conditions, merges the observations provided by onboard accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers with those of the virtual vision sensor, or VVS. The VVS is the denomination of the outputs generated by a visual inertial odometry pipeline that relies on the images of the Earth surface generated by an onboard camera as well as on the navigation filter outputs. The filter is implemented in the manifold of rigid body rotations or in order to minimize the accumulation of errors in the absence of the absolute position observations provided by the GNSS receiver. The results obtained when applying the proposed algorithms to high-fidelity Monte Carlo simulations of two scenarios representative of the challenges of GNSS-denied navigation indicate the following:

- The body attitude estimation is qualitatively similar to that obtained by a standalone inertial filter without any visual aid [2]. The bounded estimations enable the aircraft to remain aloft in GNSS-denied conditions for as long as it has fuel. Quantitatively, the VVS observations and the associated more accurate filter equations result in significant accuracy improvements when compared with the [2] baseline.

- The vertical position estimation is qualitatively and quantitatively similar to that of the standalone inertial filter [2]. In addition to ionospheric effects (which also apply when GNSS signals are available), the altitude error depends on the amount of pressure offset variation since entering GNSS-denied conditions, being unbiased (zero mean) and bounded by atmospheric physics.

- The horizontal position estimation exhibits drastic quantitative improvements over the baseline standalone inertial filter [2], although from a qualitative point of view, the estimation error is not bounded as the drift cannot be fully eliminated.

Future work will focus on addressing some of the limitations of the proposed navigation system, such as the restriction to fixed-wing vehicles (which originates when using the pitot tube airspeed readings to replace visual navigation when not enough features can be extracted from a texture-poor terrain) and the inability to fly at night or above clouds (infrared images could potentially be used for this purpose).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.; methodology, E.G.; software, E.G.; validation, E.G.; formal analysis, E.G.; investigation, E.G.; resources, E.G.; data curation, E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.; writing—review and editing, A.B.; visualization, E.G.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has received funding from RoboCity2030-DIH-CM, Madrid Robotics Digital Innovation Hub, S2018/NMT-4331, funded by R&D Activity Programs in the Madrid Community and cofinanced by the EU Structural Funds.

Data Availability Statement

An open-source C++ implementation of the described algorithms can be found at [80].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BRIEF | binary robust independent elementary features |

| DSO | direct sparse odometry |

| ECEF | Earth centered Earth fixed |

| EKF | extended Kalman filter |

| FAST | features from accelerated segment test |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| IMU | inertial measurement unit |

| iSAM | incremental smoothing and mapping |

| LSD | large-scale direct |

| MAV | micro air vehicle |

| MSCKF | multistate constraint Kalman filter |

| MSF | multisensor fusion |

| NED | north east down |

| NSE | navigation system error |

| OKVIS | open keyframe visual inertial SLAM |

| ORB | oriented FAST and rotated BRIEF |

| ROVIO | robust visual inertial odometry |

| SLAM | simultaneous localization and mapping |

| special Euclidean group of | |

| special orthogonal group of | |

| SVO | semidirect visual odometry |

| UAV | unmanned aerial vehicle |

| VINS | visual inertial navigation system |

| VIO | visual inertial odometry |

| VO | visual odometry |

| VVS | virtual vision sensor |

| WGS84 | World Geodetic System 1984 |

Appendix A. Required Jacobians

This appendix groups together the various Jacobians employed in this article. They are the following:

- The time derivative of the geodetic coordinates (longitude, latitude, and altitude) depends on the ground velocity per (A1), where M and N represent the WGS84 ellipsoid radii of curvature of meridian and prime vertical, respectively. The Jacobian with respect to , given by (A2) and employed in (20), is hence straightforward:

- The motion angular velocity represents the rotation experienced by any object that moves without modifying its attitude with respect to the Earth surface. It is caused by the curvature of the Earth, and its expression when viewed in is given by (A3). Its Jacobian with respect to , provided by (A4) and employed in (22) and (33), is also straightforward:

- The Coriolis acceleration is the double cross product between the Earth angular velocity caused by its rotation around the axis at a constant rate and the aircraft velocity. Its expression when viewed in is provided by (A5), resulting in the (A6) Jacobian with respect to , which appears in (22):

- The Lie Jacobian represents the derivative of the function , that is, the concatenation between the attitude and its local perturbation , with respect to the attitude , when the increments are viewed in their respective local tangent spaces, that is, tangent respectively at and . Interested readers should refer to [4,5] for the obtainment of (A7), where represents the direct cosine matrix corresponding to a given rotation vector . This Jacobian is employed in (48).

- The Lie Jacobian represents the derivative of the function , that is, the rotation of according to the attitude , with respect to the attitude , when the increment is viewed in its local tangent space and that of the resulting vector is viewed in its Euclidean space. is the derivative of the same function with respect to the unrotated vector , in which the increments of the unrotated vector are also viewed in the Euclidean space. Refer to [4,5] for the obtainment of (A8) and (A9), which appear on (21) and (23), respectively, and where represents the direct cosine matrix equivalent to the unit quaternion :

- The Lie Jacobians and are similar to the previous ones but refer to the inverse rotation action . Expressions (A10) and (A11), which appear on (31), (33), (37), and (39), respectively, are also obtained in [4,5]

References

- Gallo, E.; Barrientos, A. GNSS-Denied Semi Direct Visual Navigation for Autonomous UAVs Aided by PI-Inspired Priors. Aerospace 2023, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, E.; Barrientos, A. Reduction of GNSS-Denied Inertial Navigation Errors for Fixed Wing Autonomous Unmanned Air Vehicles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 120, 107237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, J. Quaternion Kinematics for the Error-State Kalman Filter. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.02508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, J.; Deray, J.; Atchuthan, D. A Micro Lie Theory for State Estimation in Robotics. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.01537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, E. The SO(3) and SE(3) Lie Algebras of Rigid Body Rotations and Motions and their Application to Discrete Integration, Gradient Descent Optimization, and State Estimation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2205.12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanalian, M.; Abdelkefi, A. Classifications, Applications, and Design Challenges of Drones: A Review. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 91, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijjahalli, S.; Sabatini, R.; Gardi, A. Advances in Intelligent and Autonomous Navigation Systems for Small UAS. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2020, 115, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.A. Aided Navigation, GPS with High Rate Sensors; Electronic Engineering Series; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, P.D. Principles of GNSS, Inertial, and Multisensor Integrated Navigation Systems; GNSS Technology and Application Series; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield, A.B. Fundamentals of High Accuracy Inertial Navigation; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 1997; Volume 174. [Google Scholar]

- Elbanhawi, M.; Mohamed, A.; Clothier, R.; Palmer, J.; Simic, M.; Watkins, S. Enabling Technologies for Autonomous MAV Operations. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 91, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, R.; Moore, T.; Ramasamy, S. Global Navigation Satellite Systems Performance Analysis and Augmentation Strategies in Aviation. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 95, 45–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippitt, C.; Schultz, A.; Procino, W. Vehicle Navigation: Autonomy Through GPS-Enabled and GPS-Denied Environments; State of the Art Report DSIAC-2020-1328; Defense Systems Information Analysis Center: Belcamp, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gyagenda, N.; Hatilima, J.V.; Roth, H.; Zhmud, V. A Review of GNSS Independent UAV Navigation Techniques. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2022, 152, 104069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Ramasamy, S.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R. UAV Navigation using Signals of Opportunity in Urban Environments: A Review. Energy Procedia 2017, 110, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluccia, A.; Ricciato, F.; Ricci, G. Positioning Based on Signals of Opportunity. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2014, 18, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.T.; Abdelkhalik, O.; Zekavat, S.A. A Weighted Measurement Fusion Kalman Filter Implementation for UAV Navigation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2013, 28, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, A.; Akhloufi, M.A. A Review on Absolute Visual Localization for UAV. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 135, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goforth, H.; Lucey, S. GPS-Denied UAV Localization using Pre Existing Satellite Imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, N. Geolocation of an Aircraft using Image Registration Coupling Modes for Autonomous Navigation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.02875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Augmented UAS Navigation in GPS Denied Terrain Environments Using Synthetic Vision. Master’s Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnari, J.; Verdoja, F.; Kyrki, V. Season-Invariant GNSS-Denied Visual Localization for UAVs. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 10232–10239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, Z. A Novel Scene Matching Algorithm via Deep Learning for Vision-Based UAV Absolute Localization. In Proceedings of the Internaltional Conference on Machine Learning, Cloud Computing and Intelligent Mining, Xiamen, China, 5–7 August 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; He, X.; Mao, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, W.; Qu, H.; Luo, K. Map Aided Visual Inertial Integrated Navigaion for Long Range UAVs. In Proceedings of the Internaltional Conference on Guidance, Navigation, and Control, Sopot, Poland, 12–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Lan, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Z. A DNN-Based Optical Aided Autonomous Navigation System for UAV Under GNSS-Denied Environment. In Proceedings of the Internaltional Conference on Autonomous Unmanned Systems, Warsaw, Poland, 6–9 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurevicius, R.; Marcinkevicius, V.; Seibokas, J. Robust GNSS-Denied Localization for UAV using Particle Filter and Visual Odometry. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2019, 30, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzza, D.; Fraundorfer, F. Visual Odometry Part 1: The First 30 Years and Fundamentals. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2011, 18, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraundorfer, F.; Scaramuzza, D. Visual Odometry Part 2: Matching, Robustness, Optimization, and Applications. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzza, D. Tutorial on Visual Odometry; Robotics & Perception Group, University of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramuzza, D. Visual Odometry and SLAM: Past, Present, and the Robust Perception Age; Robotics & Perception Group, University of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cadena, C.; Carlone, L.; Carrillo, H.; Latif, Y.; Scaramuzza, D.; Neira, J.; Reid, I.; Leonard, J.J. Past, Present, and Future of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: Towards the Robust Perception Age. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 1309–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Fast Semi-Direct Monocular Visual Odometry. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gassner, M.; Werlberger, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Semidirect Visual Odometry for Monocular and Multicamera Systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 33, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Koltun, V.; Cremers, D. Direct Sparse Odometry. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Schops, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-SLAM: Large Scale Direct Monocular SLAM. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2014, 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R. Real-Time Accurate Visual SLAM with Place Recognition. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2017. Available online: http://zaguan.unizar.es/record/60871 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Crassidis, J.L.; Markley, F.L. Unscented Filtering for Spacecraft Attitude Estimation. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2003, 26, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grip, H.F.; Fossen, T.I.; Johansen, T.A.; Saberi, A. Attitude Estimation Using Biased Gyro and Vector Measurements with Time Varying Reference Vectors. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottah, R.; Narkhede, P.; Kumar, V.; Karar, V.; Poddar, S. Multiple Model Adaptive Complementary Filter for Attitude Estimation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.A. Systematic Convergence of Nonlinear Stochastic Estimators on the Special Orthogonal Group SO(3). Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2020, 30, 3848–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.A.; Brown, L.J.; McIsaac, K. Nonlinear Stochastic Attitude Filters on the Special Orthogonal Group SO(3): Ito and Stratonovich. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 2019, 49, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, P.; Silvestre, C.; Oliveira, P. On the Observability of Linear Motion Quantities in Navigation Systems. Syst. Control Lett. 2011, 60, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.A.; Brown, L.J.; McIsaac, K. Nonlinear Pose Filters on the Special Euclidean Group SE(3) with Guaranteed Transient and Steady State Performance. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 2019, 51, 2949–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.A. GPS Denied Navigation: Attitude, Position, Linear Velocity, and Gravity Estimation with Nonlinear Stochastic Observer. In Proceedings of the 2021 American Control Conference, Online, 25–28 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.D.; Allibert, G. Riccati Observer Design for Pose, Linear Velocity, and Gravity Direction Estimation Using Landmark Position and IMU Measurements. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications, Copenhagen, Denmark, 21–24 August 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrau, A.; Bonnabel, S. The Invariant Extended Kalman Filter as a Stable Observer. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 62, 1797–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzza, D.; Zhang, Z. Visual-Inertial Odometry of Aerial Robots. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.03289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G. Visual-Inertial Navigation: A Concise Review. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.02650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stumberg, L.; Usenko, V.; Cremers, D. Chapter 7—A Review and Quantitative Evaluation of Direct Visual Inertial Odometry. In Multimodal Scene Understanding; Yang, M.Y., Rosenhahn, B., Murino, V., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, X.; Du, M.; Li, X. Computer Vision Algorithms and Hardware Implementations: A Survey. Integr. Vlsi J. 2019, 69, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaff, A.; Martin, D.; Garcia, F.; de la Escalera, A.; Maria, J. Survey of Computer Vision Algorithms and Applications for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 92, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourikis, A.I.; Roumeliotis, S.I. A Multi-State Constraint Kalman Filter for Vision-aided Inertial Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Roma, Italy, 10–14 April 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, S.; Furgale, P.; Rabaud, V.; Chli, M.; Konolige, K.; Siegwart, R. Keyframe Based Visual Inertial SLAM Using Nonlinear Optimization. Robot. Sci. Syst. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, S.; Lynen, S.; Bosse, M.; Siegwart, R.; Furgale, P. Keyframe Based Visual Inertial SLAM Using Nonlinear Optimization. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2015, 34, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloesch, M.; Omari, S.; Hutter, M.; Siegwart, R. Robust Visual Inertial Odometry Using a Direct EKF Based Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Intelligent Robot Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–3 October 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Li, P.; Shen, S. VINS-Mono: A Robust and Versatile Monocular Visual Inertial State Estimator. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynen, S.; Achtelik, M.W.; Weiss, S.; Chli, M.; Siegwart, R. A Robust and Modular Multi Sensor Fusion Approach Applied to MAV Navigation. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Intelligent Robot Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faessler, M.; Fontana, F.; Forster, C.; Mueggler, E.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. Autonomous, Vision Based Flight and Live Dense 3D Mapping with a Quadrotor Micro Aerial Vehicle. J. Field Robot. 2015, 33, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Carlone, L.; Dellaert, F.; Scaramuzza, D. On Manifold Pre Integration for Real Time Visual Inertial Odometry. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M.; Johannsson, H.; Roberts, R.; Ila, V.; Leonard, J.; Dellaert, F. iSAM2: Incremental Smoothing and Mapping Using the Bayes Tree. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2012, 31, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, M.; Nikolic, J.; Gohl, P.; Schneider, T.; Rehder, J.; Omari, S.; Achtelik, M.W.; Siegwart, R. The EuRoC MAV Datasets. IEEE Int. J. Robot. Res. 2016, 35, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmerico, J.; Scaramuzza, D. A Benchmark Comparison of Monocular Visual-Inertial Odometry Algorithms for Flying Robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M. Visual Inertial Monocular SLAM with Map Reuse. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Wang, S.; Wen, H.; Markham, A.; Trigoni, N. VINet: Visual-Inertial Odometry as a Sequence-to-Sequence Learning Problem. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/11215 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Paul, M.K.; Wu, K.; Hesch, J.A.; Nerurkar, E.D.; Roumeliotis, S.I. A Comparative Analysis of Tightly Coupled Monocular, Binocular, and Stereo VINS. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Singapore, 19 May–3 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Nuske, S.; Scherer, S. A Multi Sensor Fusion MAV State Estimation from Long Range Stereo, IMU, GPS, and Barometric Sensors. Sensors 2017, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solin, A.; Cortes, S.; Rahtu, E.; Kannala, J. PIVO: Probabilistic Inertial Visual Odometry for Occlusion Robust Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, S.; Quenzel, J.; Krombach, N.; Behnke, S. Efficient Multi Camera Visual Inertial SLAM for Micro Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 9–14 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckenhoff, K.; Geneva, P.; Huang, G. Direct Visual Inertial Navigation with Analytical Preintegration. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negru, S.A.; Geragersian, P.; Petrunin, I.; Zolotas, A.; Grech, R. GNSS/INS/VO Fusion using Gated Recurrent Unit in GNSS-Denied Environments. AIAA SciTech Forum 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geragersian, P.; Petrunin, I.; Guo, W.; Grech, R. An INS/GNSS Fusion Architecture in GNSS-Denied Environment using Gated Recurrent Unit. AIAA SciTech Forum 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasdat, H.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Davison, A.J. Real Time Monocular SLAM: Why Filter? In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010. [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.; Delbruck, T.; Orchard, G.; Bartolozzi, C.; Taba, B.; Censi, A.; Leutenegger, S.; Davison, A.; Conradt, J.; Daniilidis, K.; et al. Event Based Cameras: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 154–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueggler, E.; Gallego, G.; Rebecq, H.; Scaramuzza, D. Continuous Time Visual Inertial Odometry for Event Cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 1425–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Optimal State Estimation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 0-471-70858-5. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, J.L. A Tutorial on SE(3) Transformation Parameterizations and On-Manifold Optimization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2103.15980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, E. High Fidelity Flight Simulation for an Autonomous Low SWaP Fixed Wing UAV in GNSS-Denied Conditions. C++ Open Source Code. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/edugallogithub/gnssdenied_flight_simulation (accessed on 25 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).