Abstract

In this work, the aeroelastic stability of an aerial refueling system is investigated. The system is formed by a classical hose and drogue, and the novelty of our work is the inclusion of a grid fin configuration to improve its stability. The unsteady aerodynamic forces on the grid fins are determined using the concept of a unit grid fin (UGF). For each UGF, the unsteady aerodynamic forces are computed using the Doublet-Lattice Method, and the forces on the complete grid fins are calculated using interfering factors obtained from wind tunnel measurements for the steady case. The static equilibrium position of the system influences the linearized perturbed unsteady motion of the ensemble. This effect, together with the phase lag angle introduced to account for the unsteady aerodynamic forces in the hose, makes the flutter computation of the complete system a non-typical one. The results show that, by adding the grid fins, the stability of the refueling system is improved, delaying or annulling flutter occurrence.

1. Introduction

Aerial refueling, or air-to-air refueling (AAR), is the process of transferring fuel from one aircraft to another during flight. Although there are different methods to perform an aerial refueling process, the most widely used technique today is the hose and drogue system, in which a trailing hose with a drogue at its end is used to transfer the fuel.

Much work and many lines of research have focused on different aspects of the study of hose and drogue systems. Among them, the work of [1] should be highlighted, since it is one of the first models to analyze the static stability of the system during the refueling process. Other more recent work of interest include [2] or [3], which analyze the dynamic response of a hose–drogue system. Authors such as [4] or [5] studies the response of a system including a reel mechanism for the hose, while certain studies such as the work of [6] included nonlinear effects to simulate the response of the hose. A thorough review of the state of the art for AAR can be found in [7].

Following [8], in the whole aerial refueling process, four different phases can be considered: the stabilized flight condition, the hose deployment, the pre-contact hose-deployed condition, and the drogue-receiver aircraft contact. Focusing on the third phase, problems with the stability of the system, which are decisive in ensuring successful attachment, could appear. For that reason, recently, several research lines about the stability of the system have been developed, emphasizing how to control the drogue and the hose once they have been deployed. For example, the work of [9,10,11] presented methods for controlling an automatic refueling drogue and that of [12] studied an active control strategy based on automatic control surfaces. However, the possibility of aeroelastic problems in aerial refueling systems with hoses and drogues have barely been investigated.

This paper introduces an analysis of the possibility of flutter-type aeroelastic stability following and extending the model presented in [13]. In order to obtain reliable results, different effects such as the downwash angle induced by the tanker wake, a new modeling of the aerodynamic forces on the hose, an experimental estimation of the structural damping of the system, and the lag between aerodynamic forces and hose motion will be included. This analysis is performed, however, not for a classic hose–drogue model but for one with an active control system installed. Specifically, in this work, the stability of the system will be studied when a prototype of grid-type fins is included between the hose and the drogue.

Grid fins (also called lattice fins) are a type of flight control surface that consists of a lattice of small aerodynamic surfaces, arranged within a box. Although their classical applications have been in missiles and rockets, they have interesting advantages when used in a system such as the one presented in this work. If the grid fins have the capability of being actively controlled, they may be used to increase the stability of the refueling process, as well as to achieve an autonomous hose approach to the receiver aircraft. The aerodynamic forces generated by this type of fin have been studied in several works for the subsonic regime. For example, [14] or [15] presented experimental and analytical results of the aerodynamic forces for different grid fin configurations. Other work, such as [16], focused on analyses with computational tools. Nevertheless, due to the computational cost of solving the aerodynamics of complete fins, in this work, the aerodynamic coefficients of the grid fins will be obtained following [17], which presents a simplified model with high reliability.

The complete hose–drogue–grid fin model, as will be described in Section 2, starts from the static equilibrium position of the system. The subsequent dynamic motion will be assumed to be of small amplitude with respect to the steady configuration. Therefore, a linearization of the perturbed equations will be performed. The resulting system of equations, in which the unsteady aerodynamic forces of the grid fins will be included, allow us to analyze the aeroelastic behavior (in particular, the possibility of flutter) of the hose–drogue–grid fin system for different flight conditions and values of the parameters. All of the flight conditions considered are in the low–mid subsonic range. The results will emphasize the differences that appear between the hose–drogue system with and without the grid fin model.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 formulates the general hose–drogue–fin model. In Section 3, the aerodynamic forces generated by the grid fins, as well as their inclusion into the model, are presented. Section 4 presents the dynamic problem once the system is perturbed with a small amplitude. The flutter analysis is outlined in Section 5, and Section 6 provides the different results. Finally, the main conclusions are presented in Section 7.

2. Hose–Drogue–Grid Fin Model

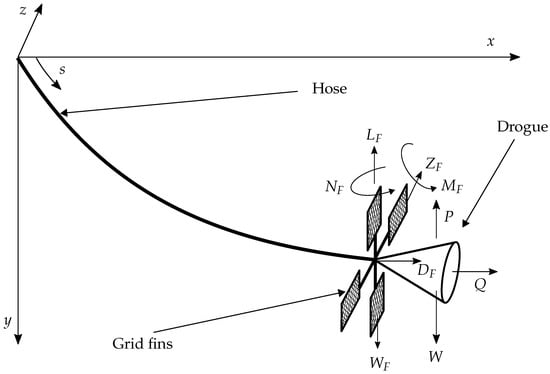

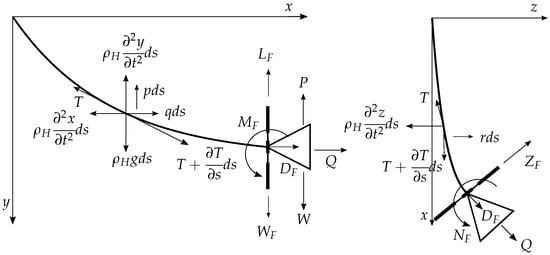

Figure 1 presents the geometry in a differential hose element, as well as at the hose–drogue–fin junction at the end of the hose. As can be seen, the reference system is defined by the x-axis opposite to the flight direction, the y-axis pointing downwards, and the z-axis forming right-handed Cartesian axes. In order to obtain the equations of the model, Figure 1 can be projected in a vertical plane and in a horizontal plane to show the acting forces in a differential hose element, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Hose–drogue–grid fin model.

Figure 2.

Geometry and active forces of the hose–drogue–grid fin model, and planes.

The governing equations for the coordinates of the hose, , and for the hose tension , with no considerations of bending forces as a first step in the model, are as follows:

where s is the hose arc length; t is the time; is the mass per unit length of the hose; c is the structural damping coefficient of the hose; q, p, and r are the drag, the lift, and the lateral aerodynamic force (all per unit length) on the hose; and is the downwash angle induced by the tanker wake. The results obtained for the hose and drogue model without grid fins showed that, in general, the configuration will be symmetrical with respect to the plane. Ro and Kamman [18] have shown that, even for the case of asymmetry of the hose–drogue system with respect to the wing location, the lateral deviation is small. Therefore, in our configuration with grid fins, as will be shown in Section 3, the lateral force on the hose, r, will be very small and can be neglected.

The drag and the lift on the hose can be written following [13], as follows:

where and are defined following the work of [19]:

where is the hose external diameter, is the friction drag coefficient, and is the zero-lift drag coefficient.

The boundary conditions of Equations (1)–(4) at the hose–tanker junction, , are as follows:

where , , and represent the prescribed motion at the hose–tanker connection. Equations (9)–(11) must be completed with geometric or kinematic boundary conditions on the derivatives of the variables at as a function of the considered case of the connection (for example, pinned, clamped, etc.). On the other hand, the boundary conditions at the hose–drogue–fin junction, , are as follows:

where is the total hose length; W is the drogue weight; P and Q are the drogue lift and drag, respectively; is the grid fin weight ( is the weight of the complete system, drogue+grid fins); is the grid fin lift; is the grid fin drag; and is the grid fin side force.

Starting from an initial static equilibrium position, the system is perturbed with a small amplitude. Hence, the four variables of the system can be expressed as follows:

where , , , and are the static equilibrium coordinates of the system and the static hose tension; is the small amplitude unsteady perturbation parameter; and , , , and are the perturbed values of the variables. With respect to , the work of [20] shows that is not affected by unsteady effects (see also, for example, [8]). Therefore, the unsteady hose tension has been assumed to be negligible. Additionally, the angle of attack of the hose can be divided in two different terms:

where is the steady angle of attack and is the unsteady angle of attack. The steady angle can be expressed as a function of the static unknowns by projecting in both axes:

As can be seen in Equations (20) and (21), the steady angle of attack includes the effect of the downwash angle induced by the tanker aircraft . The modeling of this angle is performed using the Lifting Line Theory. This angle affects the steady angle of attack and, due to the coupling between the steady and the unsteady motion (see Section 4), will also influence the dynamics of the system.

With respect to , considering the unsteady effect due to the motion of the system and assuming small angles, it can be expressed as the ratio of the vertical speed of the hose to the free-stream speed :

By projecting the angle of attack onto both axes and linearizing it, the aerodynamic forces on the hose (Equations (5) and (6)) can also be split into a steady term and a term of order :

Regarding the steady problem, a numerical integration of the resulting nonlinear system of equations yields the static equilibrium position of the system and the static tension of the hose. Afterwards, the dynamic problem, i.e., the system of equations to be obtained with the perturbed variables from Equations (15)–(17), must be resolved.

3. Grid Fin Prototype. Aerodynamic Characterization

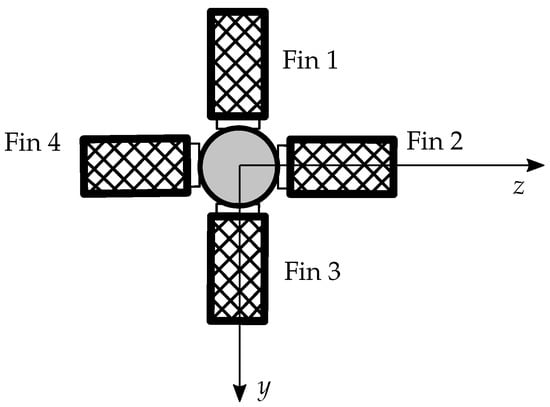

As mentioned in Section 1, in order to provide automatic control stabilization when the receiver approaches the drogue, a grid fin prototype is included at the end of the hose. The configuration of the prototype is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Grid fin prototype.

As can be seen, there are two fins in vertical position (fins 1 and 3) and two fins in horizontal position (fins 2 and 4). Each of these fins can rotate around its own axis independently of the drogue. These motions, together with the motion of the complete model in the hose–drogue–fin junction (pitch and yaw) will allow for defining a local angle of attack (rotation around the z-axis) and a local angle of sideslip (rotation around the y-axis) of each of the fins and , for .

With the addition of the grid fin aerodynamic forces, as seen in Equations (12)–(14), the static and dynamic behavior of the whole system will be altered. The method to obtain the aerodynamic forces on the grid fins is based on the work of [17], generalized in order to include the unsteady motion of the grid fins. In this reference, the complete fin was divided into unit grid fins (UGF). On each UGF, the aerodynamic forces were computed. Multiplication of the net forces acting on each UGF by the number of total equivalent UGF provided the total force on the fin. In [17], it was shown that the comparison of the results by the simplified UGF method and the solution of the complete fin is very accurate in the subsonic regime. While in this reference, the solution of the complete fin was achieved using a CFD code, in this work, the aerodynamic coefficients will be obtained with the Doublet-Lattice Method (DLM) code. With this code, a UGF normal force coefficient is calculated as a function of the Mach number and for the reduced frequency of the unsteady motion of the system . With the approach of the UGF method, the lift coefficient slopes on the vertical and horizontal fins can be expressed as follows:

where is the reference surface of a UGF; is the reference surface of a complete fin; and and are the equivalent UGF for a vertical and an horizontal fin, respectively, which are estimated following the same procedure described in [17]. It is important to point out that, due to the symmetry of the fin configuration, the side force coefficient slopes in the fins can be obtained easily from the lift coefficients: and . Once and have been obtained, it is possible to develop a formulation to calculate the aerodynamic forces on the complete fins. Contributions to the total forces, such as the interference terms between the four fins and the rest of the prototype, are obtained from experimental data, while the computations from the DLM are strictly associated with the isolated fins. Although these other contributions are always very small with respect to the fins themselves, they are included in the results used for the aerodynamic coefficients.

For the configuration presented in Figure 3, the lift and the side force coefficient for each grid fin are as follows:

for . The complete coefficients can be obtained from Equations (27) and (28):

where and are correction factors needed to include interferences and other effects obtained from experimental data. With respect to the rest of the aerodynamic coefficients, the drag coefficient is obtained from experimental data of static tests. Therefore, it will be assumed completely steady, i.e., in the perturbed equations, it will not appear. The pitch and yaw moment coefficients and are obtained in a similar way to Equations (29) and (30). However, since they will have no effect on the results (the bending and torsion of the hose are not considered in the model), these expressions are not included in this development. Once the aerodynamic coefficients are known, the grid fin forces can be expressed as follows:

In a similar way to Equations (15)–(18), the angles of attack and sideslip of the grid fins can be split into a steady and in an unsteady contribution (for a symmetric case of the grid fin configuration):

where and are the steady angle of attack and sideslip of each fin, and and are the unsteady angle of attack and sideslip of each grid fin (). Thus, Equations (27) and (28) can be rewritten as follows:

Linearizing and retaining only terms of order , the unsteady force coefficients and are as follows:

The coefficients and for the total forces are obtained with Equations (29) and (30). It can be seen that both coefficients and are functions of eight unknowns: the unsteady angles of attack and sideslip of each of the four fins. It is possible to write these two expressions in matrix form as a function of the unknowns: , where the vector of unknowns will be the following:

Additionally, the matrix is as follows:

where each coefficient of the matrix can be defined, following Equations (38) and (39), as follows:

for . Equation (41) gives the generalized unsteady force matrix of the fins as a function of their angles of attack and sideslip. To couple the aerodynamic forces on the fins with the dynamic equations on the hose, this matrix must be expressed as a function of the three perturbed variables of the dynamic problem: , and . By analyzing the fin angles at the static equilibrium position, a relationship between these angles and the static variables can be found:

where it has been assumed that the angles in the hose–fin–drogue junction are small. In Equation (47), it can be observed that the value for is very small, and therefore, the lateral forces on the hose can be neglected. Starting with fin 1, once the system is perturbed from their static position, the unsteady angles of attack and sideslip could be written, retaining terms of order , as follows:

Using the relationships of Equations (46) and (47), the angles of attack and sideslip of fin i can be expressed as a function of the perturbed variables of the system at the hose–drogue–fin connection ():

for . Equations (50) and (51) can be written as a transformation matrix between the grid fin angles and the derivatives of the perturbed variables. With this transformation matrix, the unsteady aerodynamic force matrix of the fins as a function of the unknowns is accomplished:

It should be noted that represents the dimensionless force coefficients on the fins. When added in the complete model, they will be multiplied by the dynamic flight pressure and the reference surface of the unit grid fins .

4. Unsteady Problem

With the linearization proposed in Equations (15)–(18), a PDE system of equations is obtained, where the unknowns are the perturbed variables of the system:

Additionally, the boundary conditions are as follows:

where is the unsteady grid fin force coefficients obtained from Equation (52). Applying separation of the variables, the perturbed variables of the system can be expressed as follows:

An improved model for the unsteady aerodynamic forces acting on the hose can be obtained by adding a phase lag angle between the acting unsteady aerodynamic forces on the hose and the hose dynamic motion. This phase lag angle will be introduced through the unsteady angle of attack and will affect the dynamic motion of the system:

Just as in the cases of stall flutter events (see [21]), in this work, the phase lag angle will be introduced in the system as one more parameter for flutter computation. The estimation of for different flight conditions can be obtained following the work of [22], as follows:

where is the first frequency in a vacuum of the system and is the first frequency of the system including the fluid effect. Therefore, once the frequencies of the system (which will be obtained solving the dynamic problem) are known, the estimation of can be performed with this simplified expression.

With these considerations, Equations (54) and (55) can be rewritten as follows:

Additionally, the boundary conditions can be written as follows:

Equations (65)–(67) are solved using the Weighted Residual Method (see [23]), where the spatial parts of the perturbed variables , and will be approximated by form functions . Thus, the problem formulation can be finally written in a compact matrix form as follows:

where M, B, and K are the inertia, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively; Q is the grid fin force coefficient matrix; and u is the vector that represents the degrees of freedom of the system (the horizontal, vertical, and lateral displacements of the system). Considering the different contributions, the inertia matrix can be expressed by the following sub-matrices:

where , , and are the inertia matrices of the horizontal, vertical, and lateral motions of the hose, respectively. The damping matrix can be written as follows:

where and are the damping matrices of the horizontal and the vertical motion, which will have aerodynamic and structural contributions, and is the horizontal damping term due to the vertical motion. In this matrix, there is a coupling between vertical and horizontal motion, as shown in Equation (65). Concerning the lateral motion of the hose, it has no aerodynamic damping (a fact that can be seen in Equation (67)). For that reason, terms come only from the structural damping c. With respect to the stiffness matrix, it can be written as follows:

where , , and are the stiffness matrices of the horizontal, vertical, and lateral motions of the hose, and is the coupling that appears in the horizontal stiffness matrix due to the vertical motion.

As can be seen both in the equations and in the resulting matrices, coupling terms between horizontal and vertical motion appear in B and K. However, these terms are only seen in the horizontal motion (Equation (65)), while they do not appear for the vertical one (Equation (66)). Therefore, the horizontal motion is coupled with the vertical motion, but not vice-versa, which implies that it is possible to solve the vertical motion of the system independently of the horizontal one. Furthermore, it can be noticed that the lag angle will appear in the aerodynamic contributions of B and K (for more details, see [24]).

The grid fin force matrix is formed using the following sub-matrices:

As seen throughout the development of the formulation, the terms associated with the fin forces only appear for the boundary conditions at the hose–drogue–fin connection (). Therefore, the sub-matrices of Equation (76) can be defined as matrices of zeros except in the terms corresponding to this node:

where , , N represents the position of the hose–drogue–fin junction in the matrix and is the different terms that show up in the grid fin aerodynamic matrix defined in Equation (52).

5. Flutter Analysis

The main purpose of this work is to analyze the aeroelastic behavior of the hose–drogue–grid fin system by obtaining the flutter boundaries under different flight conditions and values of the parameters. It is important to highlight that the system can be considered statically nonlinear but dynamically linear, being coupled static and dynamic problems. Therefore, the nonlinear static equilibrium position will affect the dynamic forces, unlike the classical flutter computation (see, for example, [25]). In other words, the flutter solution will be influenced by nonlinearity effects of the static configuration equilibrium. In [24], an overview for the flutter computations of this type of systems is explained. However, in this work, one of the main novelties is the inclusion of the grid fin prototype in the hose–drogue model. Thus, another important goal is to analyze the effect of the grid fins in the aeroelastic behavior of the system. Flutter analysis will be performed by means of the k-Method (see [26]). Assuming harmonic motion , Equation (72) can be rewritten as follows:

The aerodynamic force matrix is henceforth expressed as a function of the Mach number and the reduced frequency k, since the grid fin aerodynamic coefficients are a function of these parameters. As usually performed in this type of analysis, in order to reduce the number of modes of the system, a modal approximation is introduced:

where is the modal matrix of the conservative system, the columns of which include the low-frequency modes, and is the vector of modal coordinates considered. Pre-multiplying by gives

Following the k-Method, a fictitious damping coefficient g proportional to the displacement is introduced:

dividing by g and grouping the generalized mass matrix and the grid fin force matrix,

After manipulation of the different terms, Equation (83) can be written as a explicit function of the flight speed:

where the reduced frequency is written as , with being the chord of the grid fins. The eigenvalue of Equation (84) is as follows:

which can be approximated by

Procedure

The procedure to obtain the flutter boundaries in the hose–drogue–grid fin system will be the following:

- The configuration of each grid fin (and therefore the values of the angles and ) are selected.

- The flight Mach number is fixed.

- The flight altitude , and, therefore, the speed of sound and the air density are fixed. The flight speed is , and the dynamic pressure is .

- The static equilibrium position of the system at the flight speed and the flight altitude is obtained.

- From the steady position:

- (a)

- Mass, damping, and stiffness matrices of the systems M, B, and K are computed.

- (b)

- With M and K, the modal matrix of the conservative problem is , and therefore, the generalized matrices , , and are obtained. Matrix will, in general, not be diagonal, while matrices and will.

- A range of interests of the reduced frequency is selected. For each reduced frequency :

- (a)

- The unsteady force coefficient from the UGF Method is computed. Then, the unsteady grid fin force matrix Q is obtained, and with , the generalized matrix is .

- (b)

- The eigenvalues of Equation (84) for each mode are computed. Then, we obtain

- The flutter speed ;

- The damping ;

- The frequency .

- diagrams, representing and , are sketched.

- The flutter speed will be the lowest at which any of the damping coefficients becomes positive. From the diagram at this speed, the flutter frequency is obtained.

6. Results

6.1. Model Parameters

Table 1 summarizes the main parameters of the hose and drogue model.

Table 1.

Hose–drogue–grid fin model main parameters.

The hose is assumed to be fully extended in the pre-contact phase, without fuel, and without any prescribed motion of the tanker aircraft ( = = = 0). As can be seen in Table 1, the structural damping coefficient used is 1.00%. Although the damping was estimated in a dynamic test performed on a piece of hose with an approximate result of 2.20%, the value of 1.00% will be used to obtain a conservative solution of the flutter boundaries.

A wide range of flight altitudes (from 0 ft to 30,000 ft) and values of the lag angle (from 0° to 20°) have been considered. However, once the results are obtained, this parameter must be estimated following Equation (64) to check whether, under the studied conditions, this range of values can be reached.

6.2. Steady-State Validation

Before the flutter results of the system are shown, a validation of the model for the steady case is presented in Table 2 and Table 3. The calculated parameters are the same as those of the work of [18] for two different flight speeds and several flight altitudes. They are the maximum hose tension , the straight-line distance from the tanker to the drogue , the vertical distance from the tanker to the drogue , and a dimensionless variable based on the two previous parameters . The results are shown using the model proposed in this paper but without the effect of the grid fins, in order to perform a validation with the results of [18,27]. The hose–drogue data used in this comparison are = 14.33 m, = 0.0508 m, = 4.09 kg/m, and the drogue weight N.

Table 2.

Comparison of the steady results with [18]. m/s.

Table 3.

Comparison of the steady results with [18]. m/s.

Table 2 and Table 3 show that the results obtained with our model without grid fins are similar to those presented in [18]. In addition, the results are close to the flight-test values presented in [27]. For example, focusing on the vertical position of the drogue as in [18], the flight-test data show differences from 1.98 m to 2.13 m at flight speeds ranging from 100 m/s to 152 m/s regardless of flight altitude. The results from [18] show differences from 2.65 m to 3.41 m at flight speeds ranging from 97.7 m/s to 149.2 m/s, while the proposed model in this work shows a difference from 1.47 m to 2.48 m for the same range of flight speeds. With respect to the maximum value of the tension, there are some differences between both models. No values of the flight test have been given for this parameter, so no assessment can be made about which model is able to better predict this variable.

6.3. Flutter Results

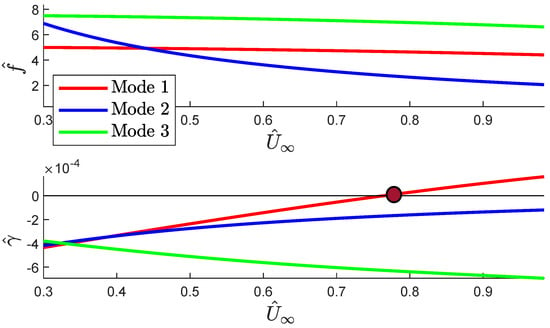

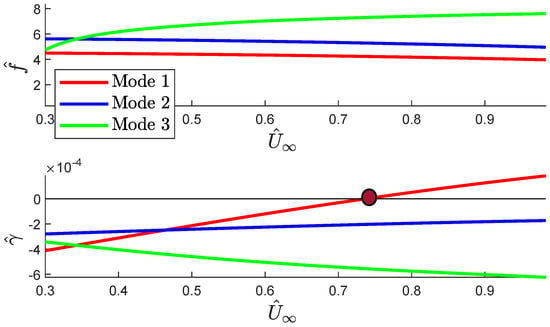

Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the evolution with the non-dimensional flight speed of the non-dimensional flutter frequencies and non-dimensional damping coefficients for the first three modes of the system. The results were obtained for a lag value of = 15° (which, as will be explained later, is the first value of where unstable cases appear) and for two different flight altitudes.

Figure 4.

diagram for the first three modes. = 15° and = 5000 ft.

Figure 5.

diagram for the first three modes. = 15° and = 30,000 ft.

As can be seen in Figure 4 and Figure 5, flutter always occurs via a single mode: there is no modal coupling in any of the studied cases. This type of flutter already appeared in the hose–drogue system without grid fins (see [13]) and can also be found in examples of stall flutter (see, for example, [21]). The flutter mode in all these cases is the first mode of the system, just like in the system without grid fins. With respect to the evolution of the damping coefficients with the speed, it can be noticed that the results for both altitudes are very similar: the flutter speed for ft is , and that for ft is . Therefore, when the flight altitude increases, the flutter speed decreases slightly. The damping coefficient for the second mode, although approaching zero for high flight speeds, does not become positive in the studied range, and the damping coefficient for the third mode becomes more stable with flight speed.

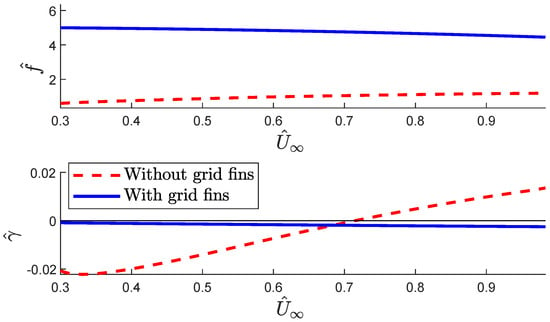

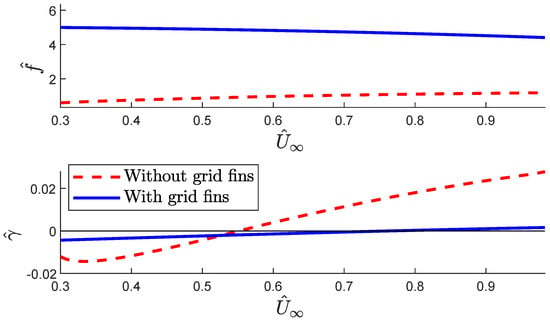

It is interesting to mention that, in the system with grid fins, the first unstable cases appeared for a phase lag angle around 15°, while in the system without grid fins (see [24]), flutter appeared for a phase lag angle around 10°. Therefore, the main conclusion is that the inclusion of the grid fins in the model increases the stability of the system, in terms of a wider range of possible lags over which the system is stable. A comparison of two cases with different values of with and without grid fins can be seen in Figure 6 and Figure 7, where the diagram for the first mode is presented.

Figure 6.

diagram comparison between the system without grid fins. = 10° and = 5000 ft.

Figure 7.

diagram comparison between the system without grid fins. = 15° and = 5000 ft.

In Figure 6, it can be seen that, for = 10°, the system without grid fins (dashed red line) reaches flutter for a certain flight speed, while the system with grid fins is stable over the whole flight speed range studied. On the other hand, Figure 7 shows that, for = 15°, the system reaches flutter both with and without grid fins. However, the flutter speed without grid fins is lower.

The variation in the non-dimensional flutter speed as a function of the phase lag angle and the flight altitude for both systems (with and without grid fins) is presented in Figure 8. As previously explained, it can be seen that, for the system without grid fins, unstable cases appear around 10° (left side of the Figure 8), while flutter in the system with grid fins appears around 15° (right side of the Figure 8). When the phase lag angle increases, the flutter speed decreases, with this reduction being less pronounced for higher values of . Concerning the flight altitude, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, when the flight altitude increases, the flutter speed decreases slightly. This effect is due to the influence of the static equilibrium position of the hose on the flutter speed.

Figure 8.

Non-dimensional flutter speed as a function of the lag angle and the flight altitude for the system without and with grid fins.

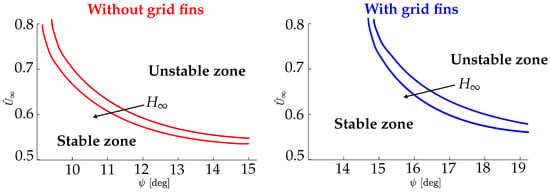

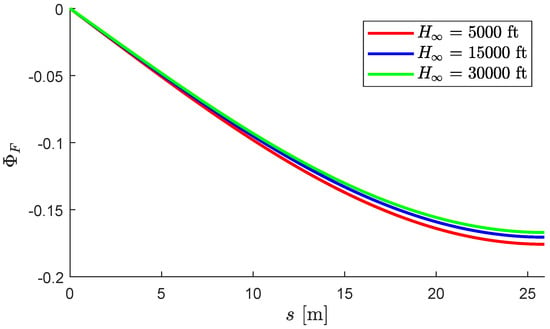

As already explained, in all cases, flutter occurs via a single mode. Figure 9 presents the flutter mode shape for a phase lag angle of = 15° and different values of the flight altitude. As can be seen, the flutter mode is barely affected by the change in the flight altitude.

Figure 9.

Flutter mode shape for different flight altitudes. = 15°.

7. Conclusions

The aeroelastic stability of a hose–drogue system with an aerodynamic grid fin model has been presented. Starting from the steady configuration of the complete system, a time linearization was performed in order to obtain the dynamic system of equations and to subsequently analyze the aeroelastic behavior.

A prototype of grid fins was included in the model with the aim of increasing the stability of the system during the refueling process. An efficient method to obtain the aerodynamic forces of the grid fins was developed.

The possibility of flutter in the complete system was studied by means of the k-Method. The results were obtained from different flight conditions and values of the phase lag angle between the unsteady aerodynamic forces on the hose and the hose motion. These results were compared with the ones obtained without the grid fin model. It was shown that the inclusion of the grid fins produces a significant increase in the aeroelastic stability of the ensemble: flutter without grid fins appears for a phase lag angle around 10°, while that with grid fins is delayed to 15°. Likewise, the same type of aeroelastic instability (one degree-of-freedom flutter) as in the case without grid fins was obtained, as was the same flutter mechanism (the first mode of the system). It was also found that results have a smooth variation with the flight altitude.

This work will continue with an analysis of different configurations of the grid fins (for example, cross configuration). Furthermore, the addition of the bending forces on the hose and the tanker wake using a vortex lattice method will complete the model for linear analysis. In this way, the hose–drogue–grid fin system will be able to analyze the most stable ensemble for an aerial refueling process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G.-F. and F.A.; methodology, P.G.-F. and K.S.P.; software, K.S.P.; validation, K.S.P.; formal analysis, P.G.-F. and K.S.P.; investigation, K.S.P. and P.G.-F.; resources, F.A. and P.G.-F.; writing-review and editing, K.S.P., P.G.-F. and F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by AIRBUS Defense and Space, Spain, under contract number D19006171.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eichler, J. Dynamic Analysis of an In-Flight Refueling System. J. Aircr. 1978, 15, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloy, A.; Khan, M. Modelling of the hose and drogue in air-to-air refuelling. Aeronaut. J. 2002, 106, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. Dynamic stability analysis of aerial refueling hose/drogue system by Finite Element Method. In Proceedings of the ASME 2008 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Boston, MA, USA, 31 October–6 November 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassberg, J.; Yeh, D.; Blair, A.; Evert, J. Numerical Simulations of KC-10 Wing-Mount Aerial Refueling Hose-Drogue Dynamics with a Reel Take-Up System. In Proceedings of the 21th AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 23–26 June 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbens, W.; Saggio, F.; Wierenga, R.; Feldmann, M. Dynamic Modeling of an Aerial Refueling Hose & Drogue System. In Proceedings of the 25th AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Miami, FL, USA, 25–28 June 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, H.; Gaston, R.; Stirling, R.; Mor, M.; Styuart, A. Numerical Simulation of Hose Whip Phenomenon in Aerial Refueling. In Proceedings of the AIAA Atmospheric Flight Mechanics Conference, Portland, OR, USA, 8–11 August 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Bhandary, U.; Bullock, S.; Richardson, T.; du Bois, J. Advances in air to air refueling. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2014, 71, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fogeda, P.; Esteban Molina, J.; Arévalo, F. Dynamic Response of Aerial Refueling Hose-Drogue System with Automated Control Surfaces. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 31, 04018110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, W.R.; Reed, E.; Glenn, G.J.; Stecko, S.M.; Musgrave, J.; Takacs, J.M. Controllable Drogue for Automated Aerial Refueling. J. Aircr. 2010, 47, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, K.; Kuk, T.; Kamman, J. Active Control of Aerial Refueling Hose-Drogue Systems. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–5 August 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuk, T.; Ro, K. Design, test and evaluation of an actively stabilised drogue refuelling system. Aeronaut. J. 2013, 117, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fogeda, P.; Arévalo, F. Dynamic stability of a hose-drogue-wing system for aerial refueling. In Proceedings of the International Forum on Aeroelasticity and Structural Dynamics, IFASD, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 28 June–2 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi Paniagua, K.; García-Fogeda, P.; Arévalo, F.; Barrera Rodriguez, J. Aeroelastic analysis of an air-to-air refueling hose-drogue system through an efficient novel mathematical model. J. Fluids Struct. 2021, 100, 103164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.A.; Burkhalter, J.E. Experimental and analytical analysis of grid fin configurations. J. Aircr. 1989, 26, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhalter, J.E.; Frank, H.M. Grid Fin Aerodynamics for Missile Applications in Subsonic Flow. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 1996, 33, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerthamalai, P.; Nagarathinam, M. Aerodynamic Analysis of Grid-Fin Configurations. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2006, 43, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikbas, E.; Baran, O.; Sert, C. Simplified Numerical Approach for the Prediction of Aerodynamic Forces on Grid Fins. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2018, 55, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, K.; Kamman, J. Modeling and Simulation of Hose-Paradrogue Aerial Refueling Systems. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2010, 33, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, S.; Larsen, A. Drag loading of circular cylinders inclined in the along-wind direction. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2007, 95, 1350–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Meguid, S. Modeling and simulation of aerial refueling by finite element method. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2007, 44, 8057–8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, E. A Modern Course in Aeroelasticity, 5th ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpkaya, T. A critical review of the intrinsic nature of vortex-induced vibrations. J. Fluids Struct. 2004, 19, 389–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, B. The Method of Weighted Residuals and Variational Principles; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi Paniagua, K.; García-Fogeda, P.; Arévalo, F. Stability and Dynamic Response of a Hose-Drogue System for Aerial Refueling. In Proceedings of the International Forum on Aeroelasticity and Structural Dynamics, IFASD, Madrid, Spain, 13–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, Y. An Introduction to the Theory of Aeroelasticity; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rodden, W. Theoretical and Computational Aeroelasticity; Crest Publishing: Birmingham, AL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.; Murray, J.; Campos, N. The NASA Dryden AAR Project: A Flight Test Approach to an Aerial Refueling System. In Proceedings of the AIAA Atmospheric Flight Mechanics Conference and Exhibit, Providence, RI, USA, 16–19 August 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).