Insurer Resilience in an Era of Climate Change and Extreme Weather: An Econometric Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

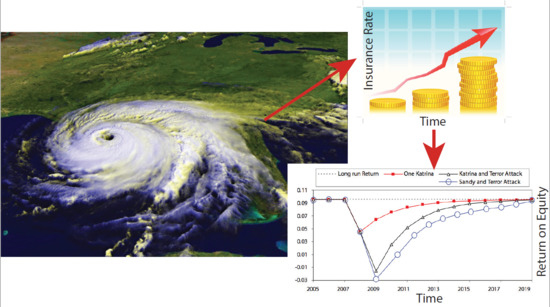

1.1. Climate, Society, and Insurance Value

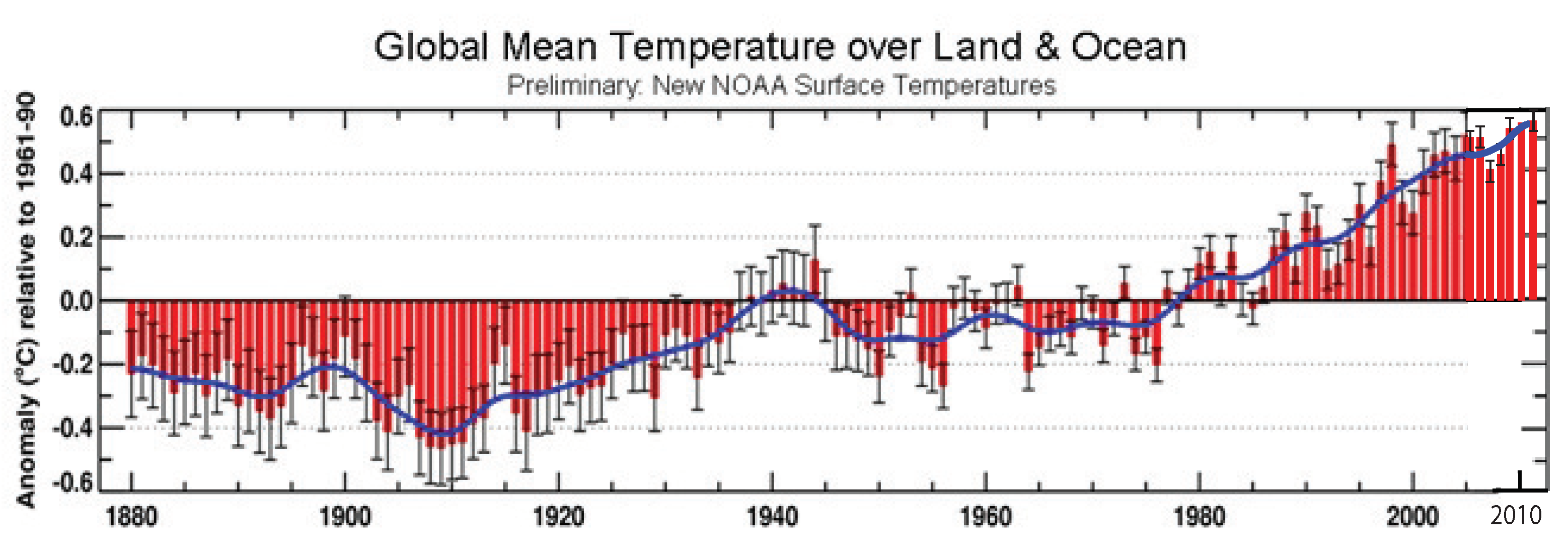

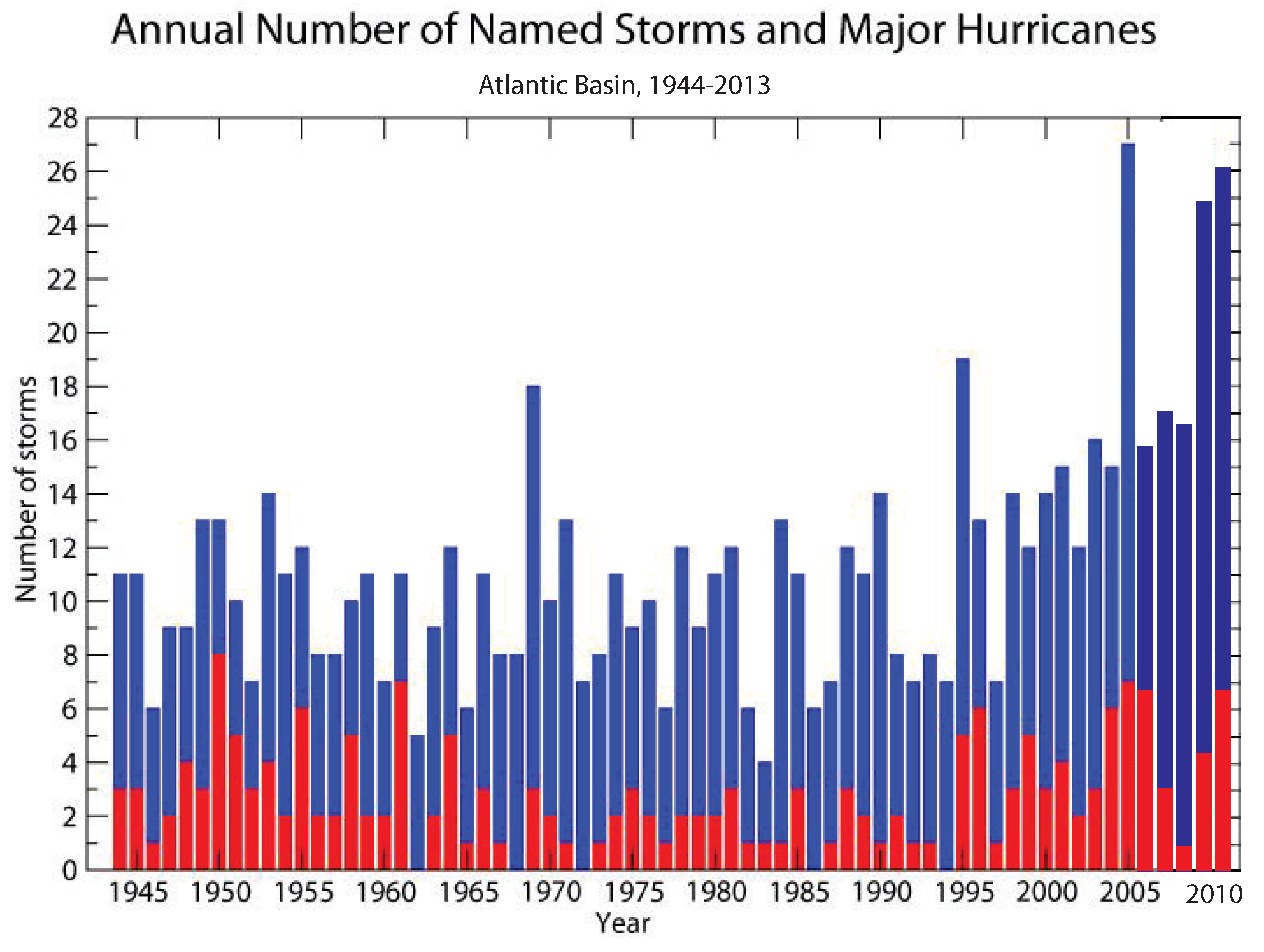

1.2. Is There a Connection between Climate Change and Hurricanes?

1.3. Problem Formulation and Insurance Response

- To what degree can the scientific uncertainty underlying the climate change/extreme weather problem be reliably characterized and evaluated by insurers and reinsurers?

- To what degree does the global climate system hold the potential for surprise to decision-makers?

- How resilient is the system to these shocks, and what actions might insurers and reinsurers take to enhance resilience and minimize the effects of these shocks?

2. Materials and Methods

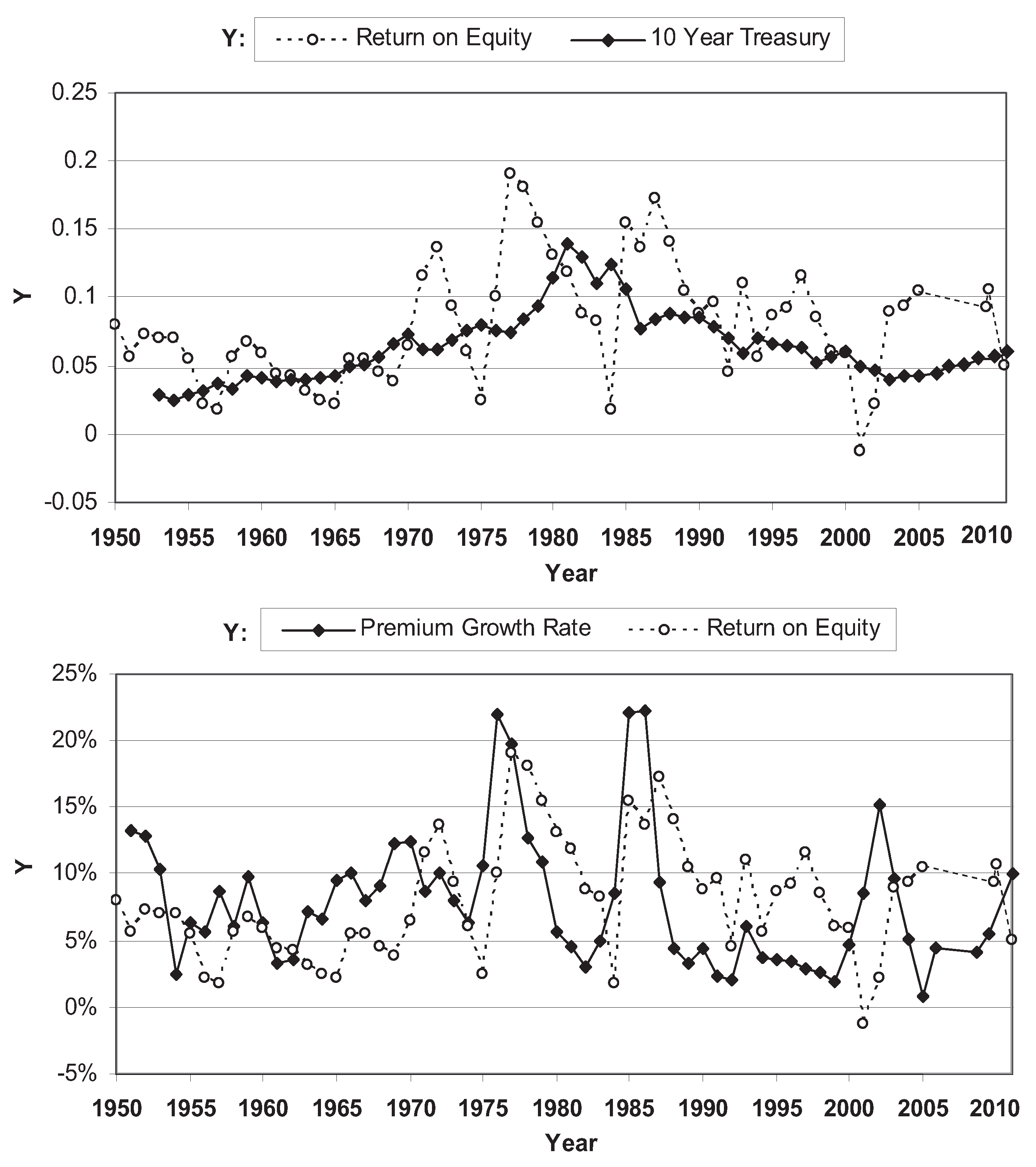

2.1. Data

2.2. Econometric Model for Estimating P/C Industry Financial Resilience

- Selection of the scenario to use in the model (no-Quartet, one/two/three Quartets, Katrina only, Katrina and 9/11, Sandy and 9/11);

- Inclusion of the scenario-based values of , , in the model;

- Calculation of and model parameters for any value of t in the time period considered;

- Monte Carlo predictions of considering sampling of pdfs of the model’s factors.

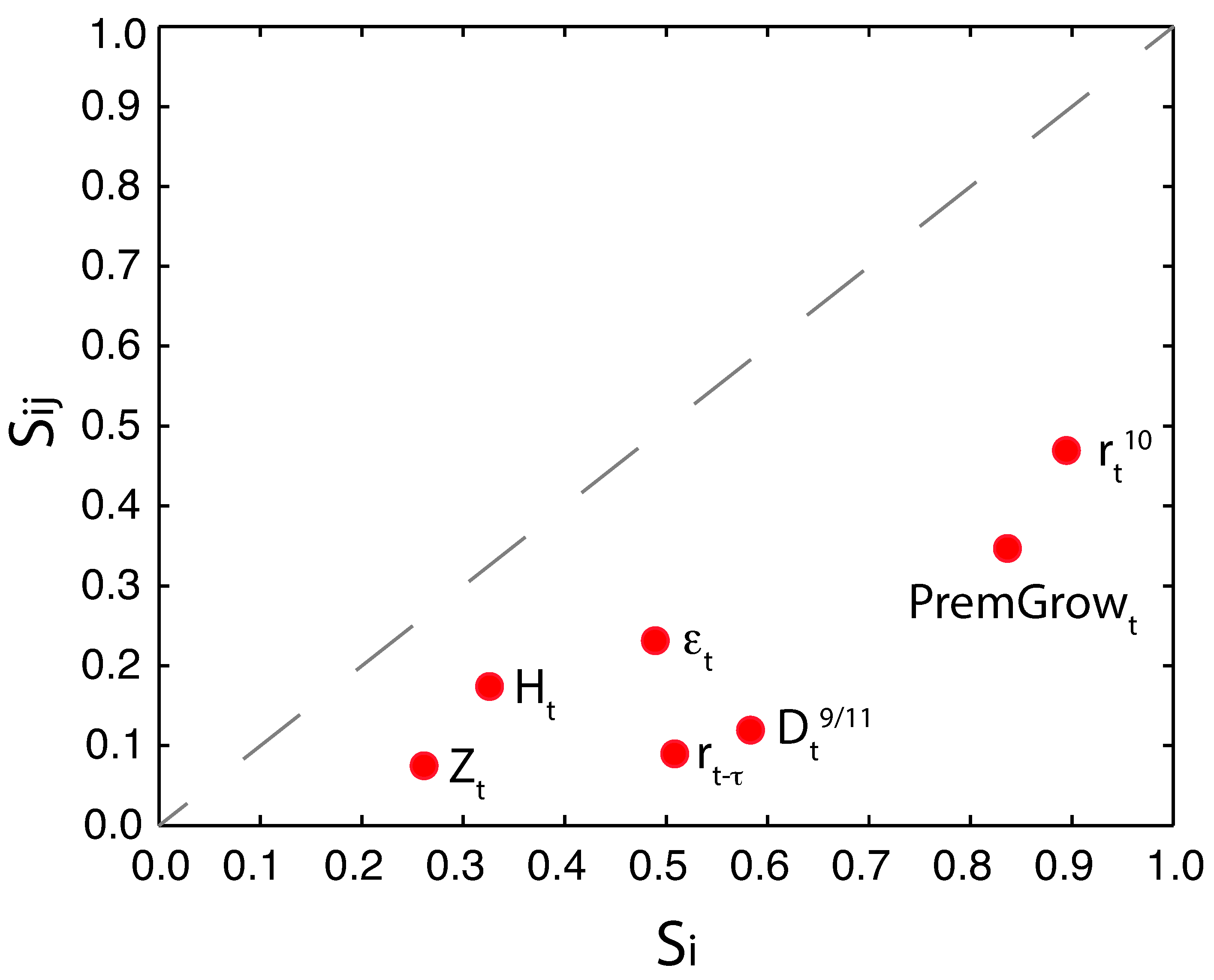

2.3. Model Choice and Global Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

3. Results

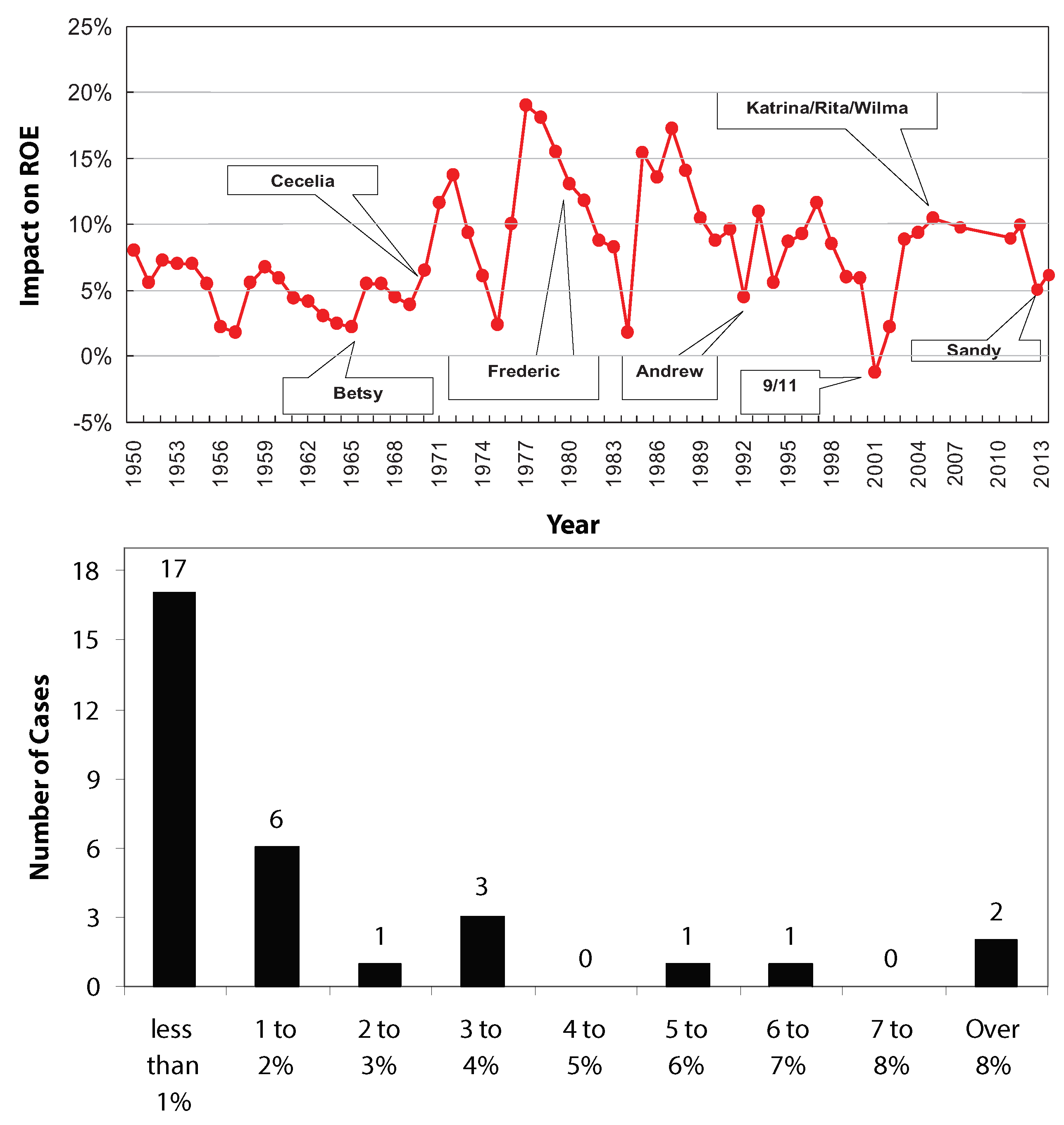

3.1. Data-Based Assessment of Impact of Hurricanes on Insurer Profitability

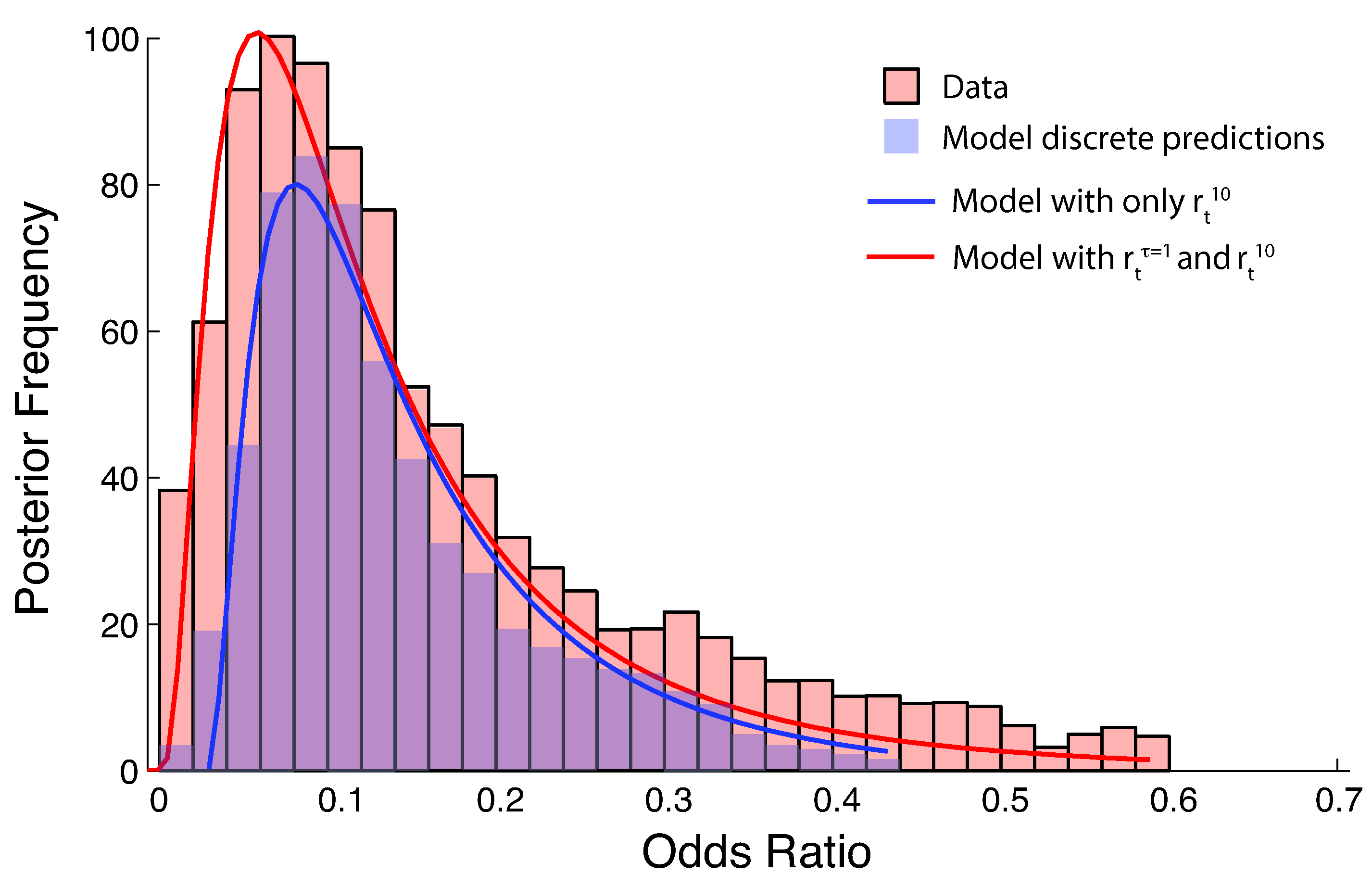

3.2. Model Selection: Predicting Extremes’ Effects on Insurance

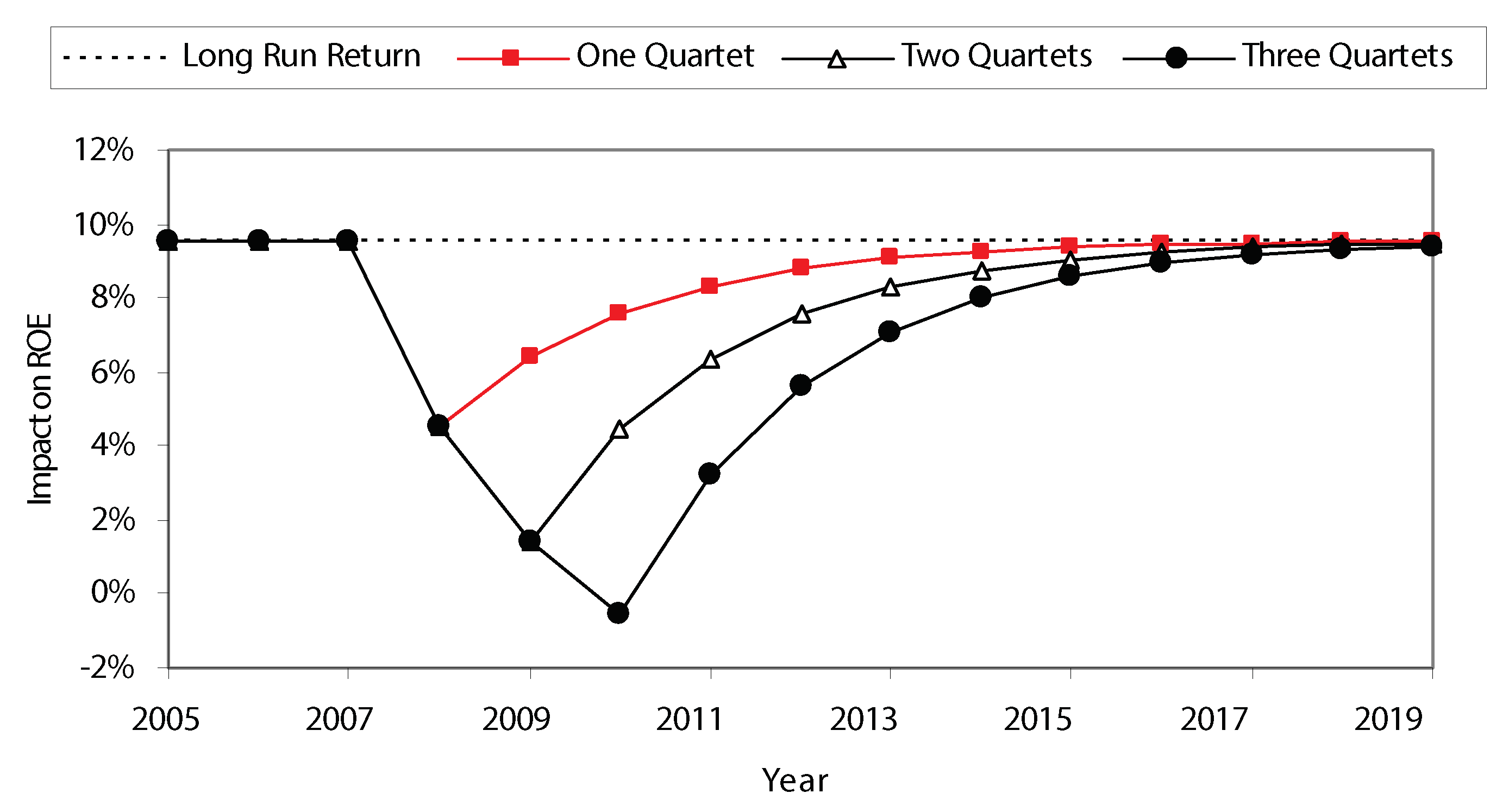

3.2.1. Stormy Weather Ahead? Hurricane Scenarios on Insurance

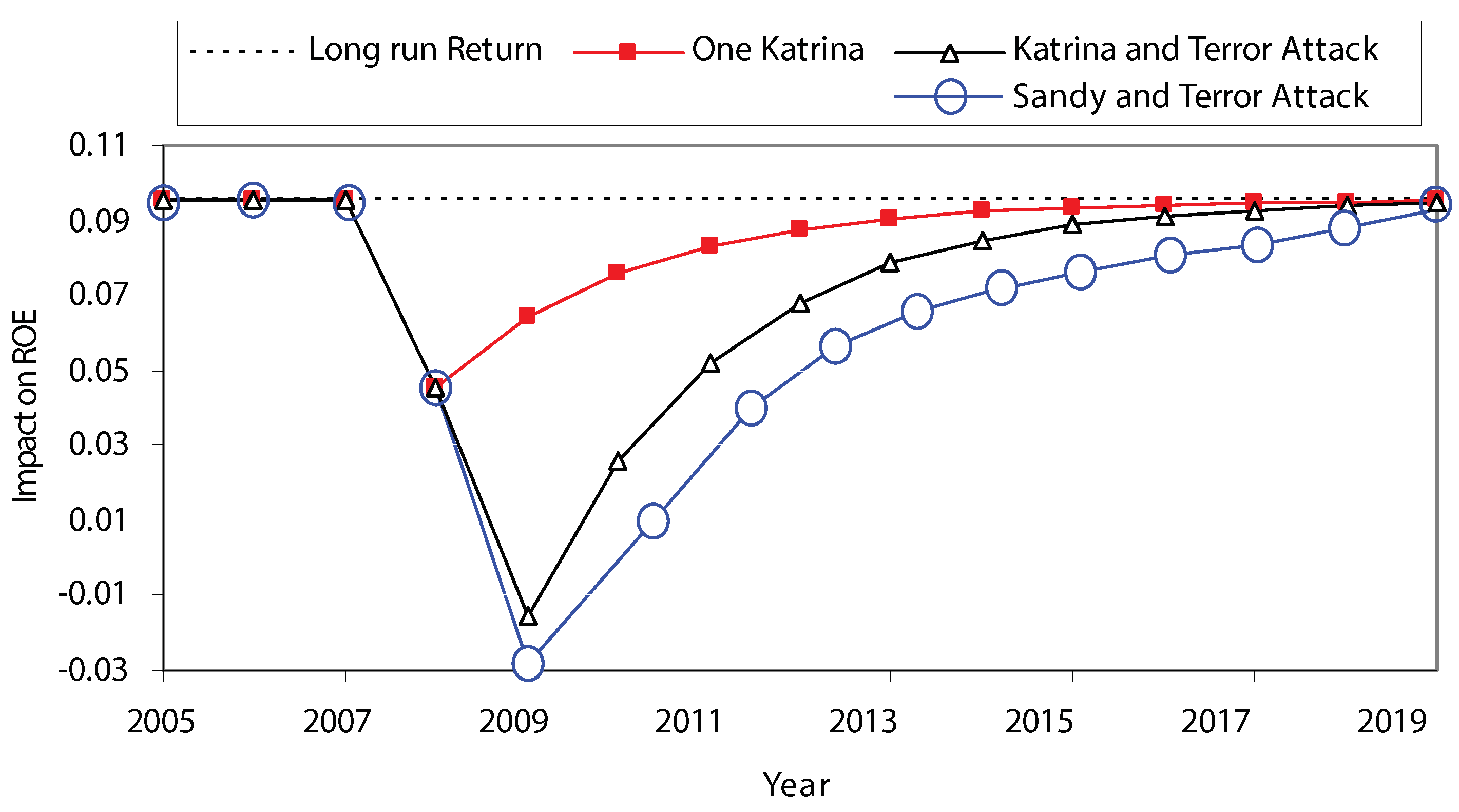

3.2.2. A Short Glimpse at a Mega-Catastrophe

- Hurricanes—even those associated with large losses—have no statistically detectable effect on the P/C industry’s return on equity;

- The losses associated with the destruction of the World Trade Center—5.02% of total policyholder surplus, as noted in Table 3—are, according to our analysis, estimated to have cut the insurance industry’s return on equity by about 8.1%;

- The WTC losses (relative to total policyholder surplus) are much less than those associated with Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (8.91%) and Hurricane Andrew in 1995 (10.41%), but are on par with those associated with the Hurricane Quartet in 2004 (5.66%).

- The losses (relative to total policyholder surplus) for hurricane Sandy are the highest of all cases considered (11.60%). Sandy was responsible for the highest absolute losses ($60B). We speculate that this outcome is, in part, related to demographic differences that, for Sandy, entailed higher property values (and the like) than those that were impacted by Katrina.

3.2.3. Model Validation

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Findings

4.2. Financial Resilience in a Larger Context

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Climate Change, Extreme Weather, and Risk

Appendix A.1. Estimating Hurricane Frequency

Appendix A.2. Estimating Hurricane Intensity

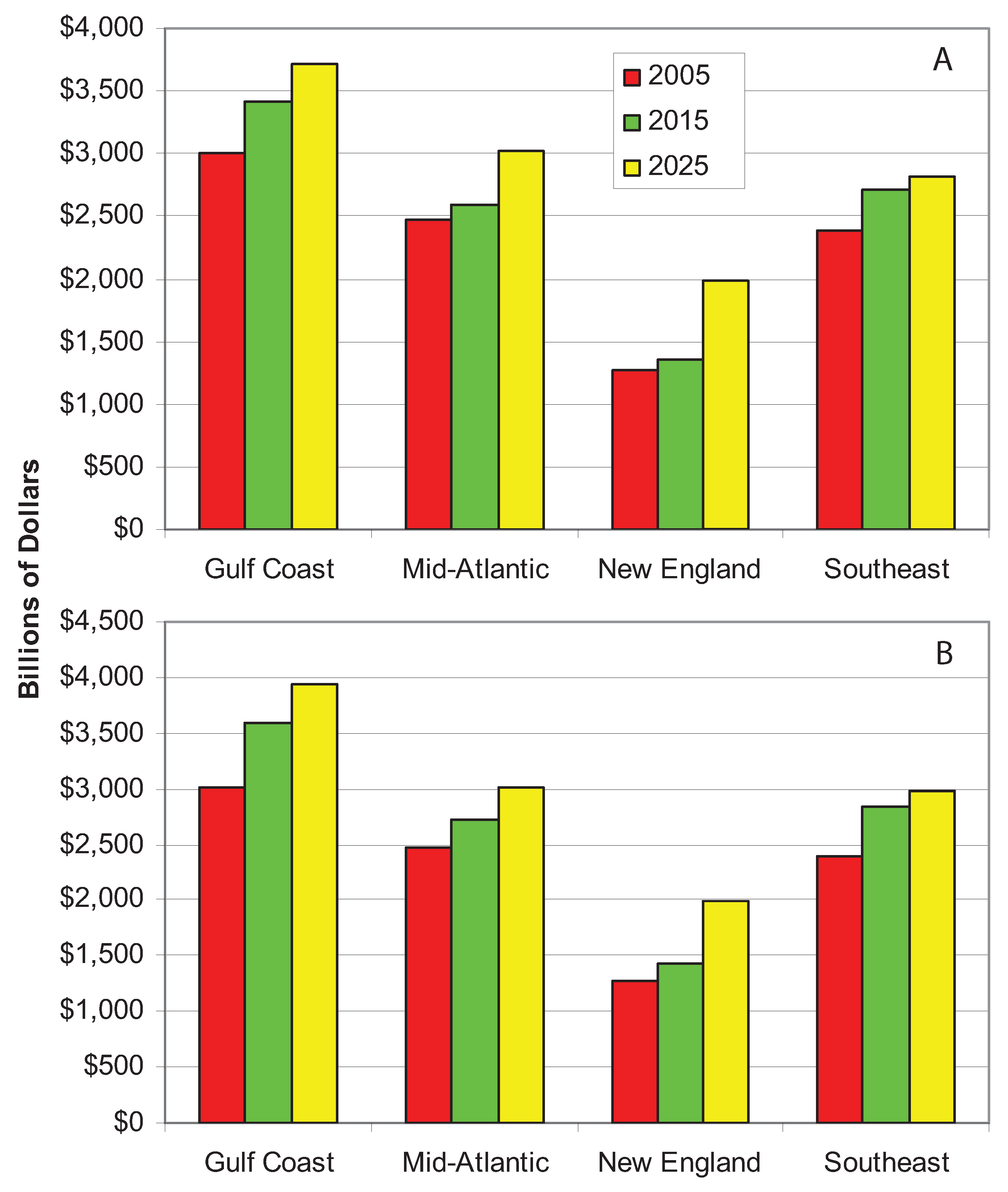

Appendix A.3. Estimating Hurricane Risk Exposure

References

- AMSC. The Changing Atmosphere–Challenges and Opportunities. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 1988, 69, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limited, C.R.M. Financial Risks of Climate Change; Technical Report; Association of British Insurers: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, E.; Roth, R.; Lecomte, E. Availability and Affordability of Insurance Under Climate Change: A Growing Challenge for the United States; Technical Report; Lawrence Berkeley Lab, University of California at Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schertzer, D.; Lovejoy, S. Non-Linear Variability in Geophysics: Scaling and Fractals; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Menabde, M.; Seed, A.; Harris, D.; Austin, G. Self-similar random fields and rainfall simulation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1997, 102, 13509–13515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, A.; Ossó, A.; Llebot, J.E. Scaling of tropical-cyclone dissipation. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, A.; Turiel, A. Variability of North Atlantic Hurricanes: Seasonal Versus Individual-Event Features. In Extreme Events and Natural Hazards: The Complexity Perspective; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, N.; Kaiser-Weiss, A.; Schmutz, W.; Thome, K.; Young, D.; Wielicki, B.; Winkler, R.; Woolliams, E. Accurate radiometry from space: An essential tool for climate studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 4028–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranger, N.; Niehorster, F. Deep uncertainty in long-term hurricane risk: Scenario generation and implications for future climate experiments. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 22, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson-Sellers, A.; Zhang, H.; Berz, G.; Emanuel, K.; Gray, W.; Landsea, C.; Holland, G.; Lighthill, J.; Shieh, S.L.; Webster, P.; et al. Tropical Cyclones and Global Climate Change: A Post-IPCC Assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.C.L.; Liu, K.S. Global Warming and Western North Pacific Typhoon Activity from an Observational Perspective. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 4590–4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. Policy: A changing climate for insurance. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2011, 1, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.M.; Pogorzelski, W.H.; Giammanco, I.M. Evaluating Hail Damage Using Property Insurance Claims Data. Weather Clim. Soc. 2015, 7, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, A. Analysis of Index Insurance Potential for Adaptation to Hydroclimatic Risks in the West African Sahel. Weather Clim. Soc. 2016, 8, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsner, J.B.; Burch, R.K.; Jagger, T.H. Catastrophe Finance: An Emerging Discipline. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2009, 90, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstone, N.J.; Smith, D.M.; Booth, B.B.B.; Hermanson, L.; Eade, R. Anthropogenic aerosol forcing of Atlantic tropical storms. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, K.; Morgan, M.G.; Grossmann, I.; Emanuel, K. Does It Make Sense To Modify Tropical Cyclones? A Decision-Analytic Assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4242–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell-Wallace, K.; Jones, M.; Hillier, J.; Foote, M. Natural Catastrophe Risk Management and Modelling: A Practitioner’s Guide; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Emanuel, K.; Lin, N.; de Moel, H.; Michel-Kerjan, E.O. Evaluating Flood Resilience Strategies for Coastal Megacities. Science 2014, 344, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convertino, M.; Foran, C.; Keisler, J.; Scarlett, L.; LoSchiavo, A.; Kiker, G.; Linkov, I. Enhanced Adaptive Management: Integrating Decision Analysis, Scenario Analysis and Environmental Modeling for the Everglades. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruijn, K.; Buurman, J.; Mens, M.; Dahm, R.; Klijn, F. Resilience in practice: Five principles to enable societies to cope with extreme weather events. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 70, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Pickering, C.; Wilkinson, S.; Dawson, R.; Mancarella, P. Power System Resilience to Extreme Weather: Fragility Modeling, Probabilistic Impact Assessment, and Adaptation Measures. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 3747–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. Hurricane Database (Hurricane Number and Strength Data, 1954–2013); Technical Report; NOAA, 2019. Available online: https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/ (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Geospatial, N. Spatial Hurricane Database; Technical Report; NOAA, 2019. Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/ (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- of the President, T.E.R. U.S. Treasury Bond Rates. Technical Report; 2019. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/ERP-2017/ERP-2017-table25 (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Institute, I.I. Annual P/C Rate of Return Data (1950–2013). Technical Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-industry-overview (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Hayashi, F. Econometrics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pankratz, A. Forecasting with Dynamic Regression Models; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdtke, N.; Panzeri, S.; Brown, M.; Broomhead, D.S.; Knowles, J.; Montemurro, M.A.; Kell, D.B. Information-theoretic sensitivity analysis: a general method for credit assignment in complex networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 2008, 5, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, S.B.; Landsea, C.W.; Mestas-Nuñez, A.M.; Gray, W.M. The Recent Increase in Atlantic Hurricane Activity: Causes and Implications. Science 2001, 293, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miljkovic, T.; Miljkovic, D. Modeling Impact of Hurricane Damages on Income Distribution in the Coastal U.S. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2014, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Sollis, R. Applied Time Series Modelling and Forecasting; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze, R. Insurance Law and Economics Research for Natural Hazard Management in a Changing Climate. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2012, 37, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffee, D.; Russell, T. Markets Under Stress: The Case of Extreme Event Insurance. In Economics for an Imperfect World: Essays in Honor of Jospeh E. Stiglitz, R. Arnott et al.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzivasileiadis, T.; Estrada, F.; Hofkes, M.W.; Tol, R.S.J. The Memory of Katrina and the Stock Market Response to Hurricane-Related News and Events; Technical Report 1417; Department of Economics, University of Sussex: Sussex, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Feria-Dominguez, J.M.; Paneque, P.; Gil-Hurtado, M. Risk Perceptions on Hurricanes: Evidence from the U.S. Stock Market. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TCFD. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate related Financial Disclosures; Final Report; TCFD: Hong Kong, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; The Fifth Assessment Report (AR5); IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde, J.; Andrews, M. Global Climate Change and Extreme Weather: An Exploration of Scientific Uncertainty and the Economics of Insurance; III Technical Report; Insurance Information Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, J.B.; Kossin, J.P.; Jagger, T.H. The increasing intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones. Nature 2008, 455, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, P.J.; Holland, G.J.; Curry, J.A.; Chang, H.R. Changes in Tropical Cyclone Number, Duration, and Intensity in a Warming Environment. Science 2005, 309, 1844–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuel, K. Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature 2005, 436, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Emanuel, K.; Oppenheimer, M.; Vanmarcke, E. Physically based assessment of hurricane surge threat under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, J.F.; Chauvin, F.; Timbal, B.; Araspin, P.; Grimal, D. A Gcm Study of the Impact of Greenhouse Gas Increase on the Frequency of Occurrence of Tropical Cyclones. Clim. Chang. 1998, 38, 307–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugi, M.; Noda, A.; Sato, N. Influence of the global warming on tropical cyclone climatology: An experiment with the JMA global model. J. Meteor. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 80, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, M.; Bister, M.; Emanuel, K. Potential Intensity of Tropical Cyclones: Comparison of Results from Radiosonde and Reanalysis Data. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 1722–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, K.A. Downscaling CMIP5 climate models shows increased tropical cyclone activity over the 21st century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12219–12224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsea, C.W.; Pielke, R.A.; Mestas-Nuñez, A.M.; Knaff, J.A. Atlantic Basin Hurricanes: Indices of Climatic Changes. Clim. Chang. 1999, 42, 89–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, K.A. The dependence of hurricane intensity on climate. Nature 1987, 326, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idso, S.; Mitchell, J. The search for CO2/trace gas greenhouse warming. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 1989, 40, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idso, S.; Balling, R.; Cerveny, R.S. Carbon dioxide and hurricanes: Implications of Northern Hemisphere warming for Atlantic/Caribbean storms. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 1990, 42, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.; Jenkis, G.; Ephraums, J. Climate Change: The IPCC Scientific Assessment; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson, T.R.; Tuleya, R.E. Impact of CO2-Induced Warming on Simulated Hurricane Intensity and Precipitation: Sensitivity to the Choice of Climate Model and Convective Parameterization. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 3477–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, P.J.; Knappenberger, P.C.; Landsea, C. Comments on “Impacts of CO2-Induced Warming on Simulated Hurricane Intensity and Precipitation: Sensitivity to the Choice of Climate Model and Convective Scheme”. J. Clim. 2005, 18, 5179–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Constant | 4.11 | 7.0 | 3.99 | 5.83 |

| (1.73) | (2.41) | (2.04) | (2.37) | |

| 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.40 | – | |

| (1.10) | (1.15) | (1.26) | – | |

| −0.27 | −0.18 | – | −0.09 | |

| (−1.32) | (−1.44) | – | (0.03) | |

| 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.21 | |

| (1.37) | (1.42) | (1.30) | (0.88) | |

| 0.31 | – | 0.27 | 0.28 | |

| (3.10) | – | (3.05) | (2.90) | |

| −7.64 | −7.85 | −6.44 | −9.11 | |

| (−0.277) | (−3.20) | (−3.11) | (−3.26) | |

| 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.26 | |

| (2.99) | (2.14) | (2.87) | (3.14) | |

| SEE | 2.000 | 2.446 | 1.923 | 1.871 |

| DW | – | 1.589 | – | – |

| Durbin h | 7.110 | – | 6.401 | 8.114 |

| 0.033 | – | 0.294 | 0.317 | |

| Time Period | 1954–2013 | 1954–2013 | 1954–2013 | 1954–2013 |

| 1 | - | - | - | |

| 0.718 | 1 | - | - | |

| −0.037 | −0.043 | 1 | – | |

| 0.066 | 0.394 | 0.029 | 1 |

| Hurricane | Year | Losses ($) | Total Surplus ($) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katrina | 2005 | 38.10 | 427.20 | 8.91% |

| Andrew | 1992 | 20.88 | 200.54 | 10.41% |

| Charley | 2004 | 7.47 | 402.26 | 1.85% |

| Ivan | 2004 | 7.11 | 402.26 | 1.76% |

| Hugo | 1989 | 6.39 | 166.44 | 3.83 % |

| Wilma | 2005 | 6.10 | 427.20 | 1.42% |

| Rita | 2005 | 4.70 | 427.20 | 1.10% |

| Frances | 2004 | 4.59 | 402.26 | 1.14% |

| Jeanne | 2004 | 3.65 | 402.26 | 0.91% |

| Georges | 1998 | 3.36 | 423.40 | 0.83% |

| WTC | 2001 | 18.80 | 374.36 | 5.02% |

| Sandy | 2012 | 68.00 | 583.50 | 11.60% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valverde, L.J.; Convertino, M. Insurer Resilience in an Era of Climate Change and Extreme Weather: An Econometric Analysis. Climate 2019, 7, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7040055

Valverde LJ, Convertino M. Insurer Resilience in an Era of Climate Change and Extreme Weather: An Econometric Analysis. Climate. 2019; 7(4):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7040055

Chicago/Turabian StyleValverde, L. James, and Matteo Convertino. 2019. "Insurer Resilience in an Era of Climate Change and Extreme Weather: An Econometric Analysis" Climate 7, no. 4: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7040055

APA StyleValverde, L. J., & Convertino, M. (2019). Insurer Resilience in an Era of Climate Change and Extreme Weather: An Econometric Analysis. Climate, 7(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7040055