Nonlinear Earth System Dynamics Determine Biospheric Structure and Function: I—A Primer on How the Climate System Functions as a Heat Engine and Structures the Biosphere

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Key Questions

- How do global climate dynamics shape regional climates and the distribution of biomes?

- How might global atmospheric and ocean circulation changes induced by increasing greenhouse gases alter terrestrial and marine regional climates?

- What do these changes mean for future biospheric structure and function and socioecological stability?

- While highly nonlinear dynamics characterize the climate system, features of these dynamics have remained relatively stable at centennial to millennial timescales. This stability results from system feedbacks that constrain climate variability (Section 2.1). This constraint creates a stable ecological “safe operating space” within which the biosphere has evolved to operate. The stability of this space is threatened by the foreseeable shift of climate regimes to outside the range of natural climate variability. This, along with the poor prospect for climate stabilization, indicates that we may expect a broad-scale reorganization of ecosystems by the end of this century (Section 2.2 and Section 2.3).

- Global circulation dynamics are driven by the Earth System functioning as a heat engine to transport excess heat from low to high latitudes (Section 3.1). This transport is accomplished by horizontal and vertical energy transfers within and among the atmosphere, oceans, and other climate system components (Section 3.2). Globally, the resulting atmospheric and ocean circulations are organized by latitude, longitude, altitude, ocean depth, and season.

- The distribution of terrestrial, open ocean, and coastal biomes is tied to regional climates, whose spatial and temporal attributes are linked to complex features of global atmospheric and oceanic circulation (Section 4 and Section 5). These biome-organizing features include, for example, the Intertropical Convergence Zone and mid-latitude Jet Streams in the atmosphere (Section 4.3) and subtropical and subpolar gyres in the oceans (Section 5.1). Other key ocean circulation features include upwelling zones and global thermohaline (density-driven) circulation (Section 5.1 and Section 5.2).

- The variety of terrestrial biomes in warm regions is greater than in colder ones. This variation is due to a thermodynamic relationship between air temperature and water vapor, where warm air can hold more moisture than cold air. Consequently, tropical, subtropical, and temperate zones have a wider range of arid to humid environments compared to colder regions (Section 4.2).

- The four points above mean that complex climate dynamics determine the distribution and structure of terrestrial and marine biomes. This is through both global atmosphere and ocean circulation dynamics and thermodynamic constraints.

- Driven primarily by elevated greenhouse gases, the Earth’s global energy budget is out of balance, retaining more energy than is released into space. Since the industrial era began, the accumulated effect of this imbalance has increased the heat energy content of climate system components and energy transfers between them (Section 3.1). Consistent with this is an observed intensification and shift in the location of atmospheric and ocean circulation patterns, which have biospheric consequences (Section 6). Such changes are currently or anticipated to be of a magnitude and character to push regional climates outside their historical ecologically safe operating space, leading to a reorganization of the biosphere with the possible emergence of novel systems.

- Observed relationships between climatic means (e.g., monthly or annual mean temperatures and precipitation) and ecological processes are not expected to hold under a changing climate. This is to say, such empirical relationships are nonstationary over time (Section 4.1.1). This arises because climatic controls over key biotic processes operate at timescales other than captured by long-term monthly or annual means. Instead, determining factors are often event-level climate dynamics (i.e., weather events) or legacy dependent (e.g., constrained by previous years’ climate). These dynamics respond nonlinearly to changes in global circulation patterns. Consequently, ecological models based on mean climate–ecology relationships, such as climate envelope distribution models, have limited utility in assessing climate change impacts (Section 4.1.2).

- Rapid disruption of climate and the biosphere threatens the provision of ecosystem services, with severe consequences for human socioeconomic systems (Section 7.3). Environmental instability additionally puts biodiversity at risk at genetic, population, community, and seascape/landscape scales. Uncertainty associated with these threats poses a challenge for biodiversity conservation, resource management, and adaptation of socioecological systems. Resource managers and conservation practitioners are well situated to implement vulnerability-based strategies due to their focus on site to regional scales, their detailed knowledge of species and ecosystems of concern, their involvement with local communities, and the need to act without complete information (Section 7.4).Box 1. Figure 1. Graphical summary illustrating key linkages between Earth System dynamics and biospheric structure and function and disruption pathways under anthropogenic-altered forcing. [Credits: Left—image from CERES Radiation Balance, NASA Scientific Visualization Studio, https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/4794. Accessed 9 June 2023. Center—ocean circulation graphic from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20706629. Accessed 3 November 2025. Right—image from NASA SeaWiFS Global Biosphere Composite 1997–1998. https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/SeaWiFS/BACKGROUND/Gallery/biosphere.jpg. Accessed 3 November 2025. All public domain].Box 1. Figure 1. Graphical summary illustrating key linkages between Earth System dynamics and biospheric structure and function and disruption pathways under anthropogenic-altered forcing. [Credits: Left—image from CERES Radiation Balance, NASA Scientific Visualization Studio, https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/4794. Accessed 9 June 2023. Center—ocean circulation graphic from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20706629. Accessed 3 November 2025. Right—image from NASA SeaWiFS Global Biosphere Composite 1997–1998. https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/SeaWiFS/BACKGROUND/Gallery/biosphere.jpg. Accessed 3 November 2025. All public domain].

1.2. Review Objectives

1.3. Terms Defined

2. Biosphere Stability and Earth System Dynamics

- Regional climates operate within a limited range of variability maintained by Earth System dynamics.

- Strong forcing results in this range being exceeded, causing climatic and ecological reorganization and potentially giving rise to novel states.

- Once this forcing abates, climatic and biospheric stabilization to these states will be slow and potentially irreversible on human timescales due to system feedbacks.

2.1. Stationary Envelope of Normal Variability

2.2. System Reorganization

2.3. Climate Stabilization

3. The Planetary Heat Engine and Global Atmospheric and Oceanic Circulation

3.1. The Climate System as a Heat Engine

3.2. Global Atmospheric and Ocean Circulation Driven by the Planetary Heat Engine

3.2.1. Planetary Circulation Systems

- The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ);

- Subtropical High-Pressure zones;

- Mid-latitude westerly Jet Streams and embedded cyclonic storms;

- Polar High-Pressure zones.

- Westward equatorial currents and eastward equatorial countercurrents;

- Mid-ocean subtropical gyres (with anticyclonic circulation);

- Eastern boundary currents;

- Western boundary currents;

- Mid-latitude and subpolar eastward currents;

- Subpolar gyres (with cyclonic circulation);

- Subpolar and polar westward currents.

3.2.2. Global Heat Energy Transfers Accomplished by Planetary Circulation Systems

- In the tropics and subtropics, the primary atmospheric circulation is the Hadley Circulation, a thermally direct, vertically overturning circulation (Figure 4a). The Hadley Circulation consists of two Hadley Cells roughly on either side of the equator rotating in opposite directions vertically (the Southern Hemisphere cell is roughly a mirror image of the Northern Hemisphere cell in Figure 4a).

- The Hadley Circulation is driven by high solar heating in the tropics and the convergence of the Trade Winds in the ITCZ (Figure 3 and Figure 4a). Solar radiative energy powers heating at the surface and high rates of evaporation. The latter is most important over the oceans. The Trade Wind convergence forces a lifting of the Trades’ warm moist air. This air cools on lifting, resulting in water vapor condensation, cloud formation, and high precipitation. The release of latent heat from condensation additionally powers the ITCZ’s deep convection (to altitudes of 15–20 km). In this way, the Hadley Circulation is fueled largely by the conversion of latent heat energy to kinetic energy and then, with lifting, to potential energy [136]. The return flow aloft transports energy poleward. This transport is strongest between 10 and 30° N/S latitude [137].

- As the air aloft cools, it sinks into the subtropics until roughly 30° N and S (Figure 4a). The subsiding air suppresses cloud formation and precipitation and creates the arid Subtropical High-Pressure zones. This is the descending branch of the Hadley Circulation (Figure 4a). The Trade Winds are the return flow at the surface, completing the Hadley Circulation.

- From the tropics to the mid-latitudes, poleward heat transport is also accomplished by the oceans, primarily in subtropical gyre western boundary currents (Figure 6). These currents include the Gulf Stream and Kuroshio, as well as those along the eastern coasts of Brazil, South Africa, and Australia. This transport is strongest between 5 and 40° N/S latitude [138,139]. The subtropical gyre eastern boundary currents return cold water equatorward off the mid-latitude and subtropical west coasts of North and South America, Europe, Africa, and Australia (Figure 6).

- From the subtropics, the continuation of thermally direct atmospheric flow to the poles is constrained by the rotation of the Earth (the Coriolis effect). This dynamical constraint turns the winds to the east, forming the Mid-latitude Westerlies and, where strongest, the Mid-latitude Jet Stream (Figure 3 and Figure 4a). This turning results in a mid-latitude buildup of low-latitude warm air against higher-latitude cold air, forming a strong meridional temperature gradient.

- Fronts form where these warm and cold air masses meet. For example, in the mid-latitudes, the convergence of warm subtropical air and mid-latitude or subpolar cold air forms the Polar Front (Figure 4b).

- Similarly, fronts form in the upper ocean where warm and cold surface currents meet. In the mid-latitudes, poleward-moving subtropical gyre warm water intersects equatorward-flowing colder subpolar gyre water (e.g., the Gulf Stream and Labrador Current in the western North Atlantic; Figure 6). The convergence forms a strong oceanic mid-latitude temperature gradient. The ocean’s temperature gradient supports the development of the troposphere’s mid-latitude meridional temperature gradient [140].

- From the subtropics and through the mid-latitudes, atmospheric energy transport is largely by synoptic scale, mid-latitude cyclonic storms [141]. These storms dissipate the mid-latitude temperature gradient by mixing warm air poleward and cold air equatorward. They act primarily in the horizontal, with warm air circling around on the east side of the storm, and cold air circling on the west. Where they meet, either warm air overruns cold or cold air runs under warm air. In both cases, warm air is lifted, leading to condensation, cloud formation, and precipitation. The release of latent heat from condensation further powers these storms, boosting poleward energy transport. This energy transport is strongest between 30 and 60° N/S latitude [137,138]. These storms are the main source of wintertime precipitation in the mid-latitudes. In the Northern Hemisphere, favored locations for storm initiation are Aleutian and Icelandic Low-Pressure centers (Figure 3a).

- At higher latitudes, mid-latitude and subpolar air masses meet yet colder polar air, forming a shallow, high-latitude meridional temperature gradient and corresponding Arctic (Antarctic) Front in the Northern (Southern) Hemisphere (Figure 4a,b) [142]. In the Northern Hemisphere summer, Arctic Front development is supported by the sea–land contrast between the open Arctic Ocean and adjacent continents and land-cover feedback arising from the contrast between the boreal woodland and adjacent tundra [130,143]. Associated with the high-latitude meridional temperature gradient are summer Arctic cyclonic storms which transport heat to the polar cap [143,144].

- In the Northern Hemisphere oceans, subpolar gyre eastern boundary currents continue heat transport poleward (Figure 6). This is particularly important in the North Atlantic, where the North Atlantic and Norwegian Currents transport Gulf Stream warm water into the Arctic Ocean. Cold water is returned in the subpolar gyre western boundary currents, for example, off the coasts of Greenland, Labrador, and the Kamchatka Peninsula (Figure 6).

- Highly structured with distinct processes governing each region of the atmosphere and oceans, including characteristic atmosphere–ocean exchanges of heat, moisture, and momentum;

- Highly nonlinear in how these processes operate and interact to produce key features of atmospheric and ocean circulation.

4. Earth System Dynamics and Terrestrial Biomes

4.1. Terrestrial Biomes and Mean Climate

4.1.1. Nonstationarity of Biome–Mean Climate Relationships

4.1.2. Climate Nonstationarity and Empirical Ecological Models

4.2. Phase-Change Thermodynamic Constraints on Terrestrial Biomes

4.2.1. Precipitation Regime Expansion Under Increasing Temperatures

4.2.2. Uneven Shape of the Climate Space Envelope

4.3. Planetary Atmospheric Circulation, Climate Regimes, and Terrestrial Biomes

4.3.1. Climate Regimes

- A range of physical conditions considered at sub-daily to multidecadal timescales. Key elements of terrestrial climate regimes include temperature, precipitation, solar radiation, cloud cover, and wind.

- General uniformity of climatic properties and processes over a region. This spatial coherence extends across a range of timescales (e.g., hourly to decadal) such that regimes are characterized as much by daily event structure and teleconnections as they are by their long-term annual and seasonal means.

- Boundaries between regimes are linked to strong between-region gradients in climatic variables such as temperature and moisture or to a specific key bioclimatic factor. An example of the latter is the seasonal occurrence of freezing temperatures, which limits the distribution of tropical vegetation.

- Linkage to broad-scale atmospheric and adjacent ocean circulation dynamics. In this way, global circulation dynamics and continental and ocean basin physiography are the defining context for a regime.

- Close correspondence to biotic regions. This is reflected in that many climate classification systems are delineated by (or at least guided by) biomes or smaller biogeographic divisions (e.g., [152,153,204]). Conversely, many ecological regionalization schemes are defined by a consistency in climate regime [149,198,205].

- Significant within-regime spatial heterogeneity. While regional-scale processes pervade across a climate regime and contrast with those in neighboring regimes, there is significant within-regime spatial heterogeneity. Within the context of overall regime features, this heterogeneity arises from (1) broad latitudinal/longitudinal gradients due to varying intensity of prevailing atmosphere circulation dynamics and (2) finer-scale changes in temperature, precipitation, and other surface variables that reflect heterogeneity in, for example, physiographic features.

4.3.2. Biomes and Circulation Features

- The transition from tropical wet to dry forests and savannas to subtropical xeric shrublands (Figure 7) is set by rainy season length. That, in turn, is set by the seasonal swing of the ITCZ’s rain band (Figure 3). The ITCZ seasonal position generally “follows the sun” with a lag. In dry tropical forests, rains are limited to summer months, with yet fewer months in savannas and dry shrublands as ITCZ influence tapers off [212]. This creates a biogeographical pattern mirrored about the equator of dry–wet–dry bands of vegetation, which is most notable in western and central Africa as one travels southward from the Sahel through the Congolian rainforest to the Kalahari Desert (Figure 7).

- Other wet tropical forests (Figure 7) are found beyond the realm of the ITCZ. These forests are tied to the Trade Winds and summer monsoons (Figure 3). When uplifted by highlands, these strong moist flows produce orographic precipitation. As part of the Hadley Circulation, the position and intensity of the Trade Winds are linked to ITCZ dynamics. The strength of summer monsoonal flow is governed by the intensity of summertime mid-continental heating in contrast to cooler nearby subtropical or tropical oceans. Some Trade Wind forests are separated by a dry zone from their equatorial counterparts (Figure 7). Consequently, these forests have developed highly endemic floras and faunas [213]. Examples are the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil and Western Ghats of southwestern Indian, which are disjunct from the Amazon and Burmese–Southeast Asian forests, respectively.

- Subtropical biomes shift with longitude from hot deserts on the west to subtropical moist forests to the east (Figure 7). This change depends on location relative to Subtropical Highs. Subtropical deserts are dominated by subsiding air from the center of Subtropical Highs, suppressing precipitation (Figure 3, Figure 4a and Figure 9a). Examples are the Sonoran and Atacama Deserts. On the eastside of continents, subtropical forests receive summertime moisture from poleward circulation around the western side of the Highs (Figure 3 and Figure 9a). This flow can extend inland, supplying moisture to warm temperate forests, such as in the southeastern United States and East Asia (Figure 7). Summer monsoons can also drive this moist flow inland.

- Mediterranean-type biomes (“sclerophyllous vegetation” in Figure 7) have summer-dry and winter-wet climates. These are generally on the west side of continents and poleward side of Subtropical Highs. In summer, they are dominated by the dry subsiding air of the Subtropical High (Figure 3). In winter, the High retreats equatorward, replaced by Mid-latitude Westerlies. The Westerlies bring mid-latitude cyclonic storms and wintertime precipitation. This is illustrated by the summer-to-winter equatorward shift of Subtropical Highs and Mid-latitude Westerlies (e.g., Figure 3b to 3a for Californian and Figure 3a to 3b Chilean Mediterranean biomes).

- Transitions from subtropical to warm and cold temperate biomes, whether forest or drylands (Figure 7), are determined by the seasonal position of the Polar Front (Figure 4b). In the Northern Hemisphere, the more poleward transitions to boreal forest, forest–tundra woodland, and Arctic tundra (Figure 7) are controlled by the seasonal swing of the Arctic Front (Figure 4b). Polar and Arctic Front seasonality is reflected in seasonal shifts in the relative dominance of subtropical, mid-latitude, subpolar, and polar air over these regions and generally follows changes in radiative balance (Figure 2b). The seasonal occurrence of subfreezing weather tied to colder air masses exerts a strong control over these biome [149]. Across these biomes, plant and animal communities change in their composition depending on species tolerances to freezing.

- In the Polar Highs, subsiding cold, dry air (cA in Figure 4b) spreads equatorward from polar regions, forming Arctic and Antarctic Fronts. In the Northern Hemisphere summer, the prevalence of this air corresponds to southward transitions from polar deserts through Arctic tundras to the boreal treeline (Figure 7). This treeline is the northern limit of the boreal woodland (coniferous forest–tundra, Figure 7) and roughly corresponds to the mean summer position of the Arctic Front [130,131,214]. The boreal forest’s southern limit generally follows the mean wintertime position of the Arctic Front. In the Southern Hemisphere, a corresponding Polar High dominates the Antarctic continent. Where ice-free, Antarctic terrain is a polar desert, such as in the Dry Valleys of Antarctica. The continental extremely cold, dry air extends equatorward to just off the continent’s edge throughout the year. There, it meets maritime subpolar air, forming the Antarctic Front.

- In the Northern Hemisphere, extratropical biome transitions vary strongly with longitude. Temperate, boreal, and Arctic biomes lie father north on the west sides of the northern continents and to the south on eastern sides (Figure 7). This pattern is set by Northern Hemisphere ocean–continent contrasts. Climates on the western side of these continents are strongly influenced by the moderating effects of adjacent oceans. This maritime influence is brought inland by westerly atmospheric flow and is illustrated by the northward extent of brown, green, and light-blue temperature color bands in Europe in Figure 9b. On the other hand, winter climates on the eastern side of these continents are strongly influenced by atmospheric circulation from cold continental interiors (e.g., darker blues in northeastern Asia in Figure 9b). This west-to-east contrast in air mass source is the key determinant of longitudinal variation in the otherwise latitude-controlled distribution of temperate, boreal, and Arctic biomes [128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135] (Figure 7).

- Across temperate regions, west-to-east biome transitions follow a wet–dry–wet sequence. These transitions run from forests to grasslands or shrub deserts and then back to forests. This pattern is observed from western to eastern temperate North America and from western Europe through central Eurasia to East Asia (Figure 7). In boreal North America, the transition is from xeric to mesic needleleaf forests (e.g., western versus eastern Canada, not distinguished in Figure 7) [215]. These moisture gradients arise primarily from mid-latitude cyclonic storms losing their moisture as they track from west to east. Moisture loss is from orographic precipitation in western mountain systems (e.g., in North and South America) and with distance from upstream moisture sources (Eurasia). Transitions back to mesic biomes occur when storms are reinvigorated as they travel further eastward. There, they draw on new sources of moisture from adjacent oceans (such as the Gulf of Mexico and the China Sea).

- In Siberia, deciduous needleleaf (Larix spp.) boreal forests (B(d) in Figure 7) replace evergreen needleleaf boreal forests that are found at the same latitudes in western Eurasia and Canada. The distribution of Larix forest is tied to the wintertime presence of extremely cold Arctic air extending as far south as Mongolia and northern China. In summer, on the other hand, the deciduous forest climate is like that of the evergreen forest. Both forests are to the south of the mean summertime location of the Arctic Front [214], such that there is sufficient growing season warmth to support tree growth [216]. In winter, the Siberian deciduous boreal forest climate is more like the climates of the polar desert and Arctic tundras than of the evergreen forest. Deciduousness and other adaptations make Larix species well adapted to the extreme cold [217,218].

5. Earth System Dynamics and Ocean Biomes

5.1. Wind-Driven Ocean Circulation Systems and Biomes

5.1.1. Physical Regimes

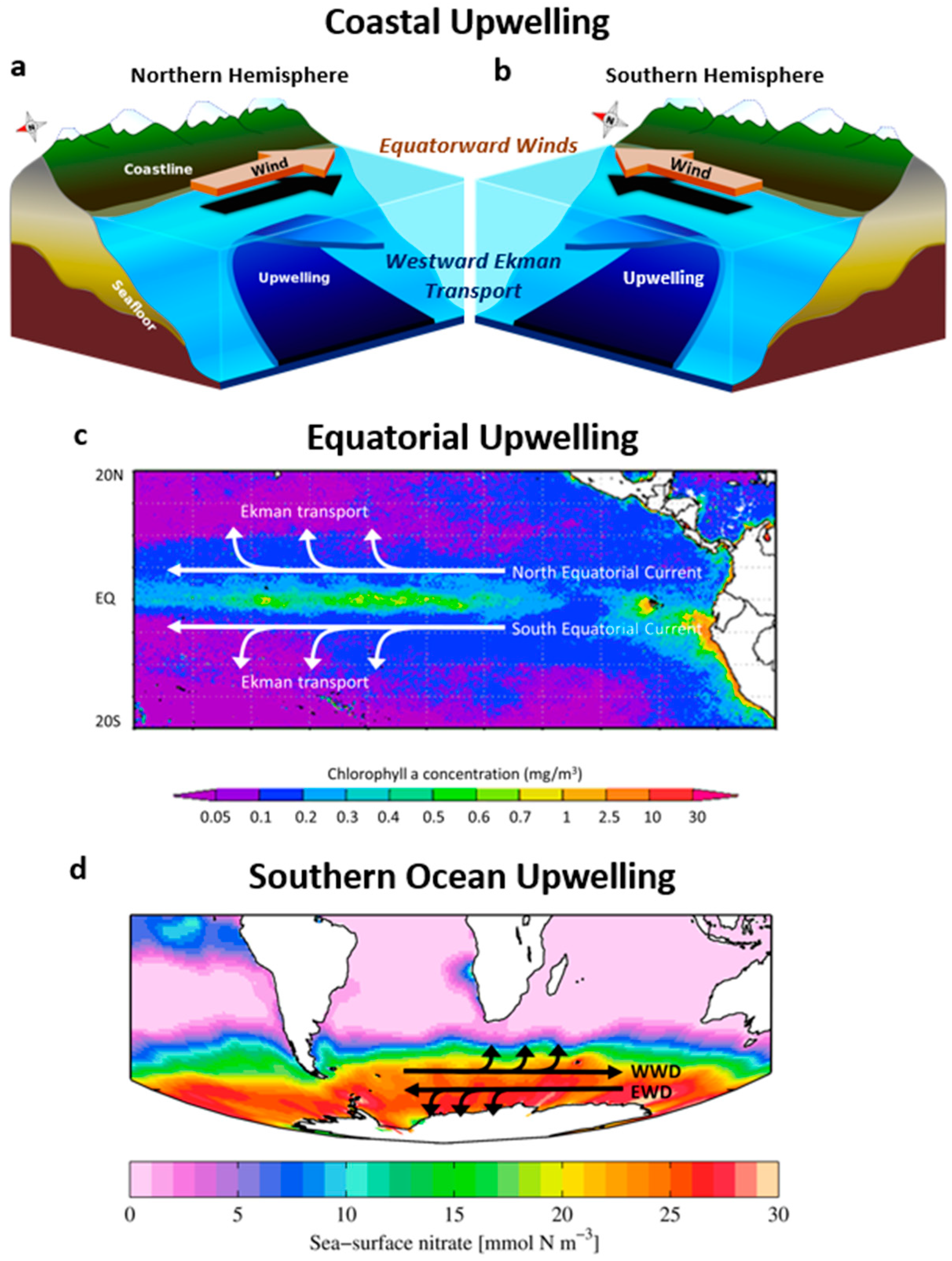

- Intermediate or deep water forced to the surface when they encounter basin barriers (e.g., sea mounts and continental margins);

- Offshore winds driving surface waters away from the coast, replaced by upwelling water;

- Sustained winds parallel to continental margins or a combination of parallel wind systems, resulting in surface water divergence and upwelling of deeper water.

- Sea surface and vertical profiles of temperature, salinity, pH, and dissolved oxygen;

- Primary production, indicated by surface chlorophyll a concentration (Figure 11);

- Seasonality of net solar radiation at the surface, influencing primary production and surface-layer heating;

- Euphotic zone depth (as a function of transparency) and nutrient concentrations (reactive N, Fe, PO43−, and Si);

- Ocean basin geography, e.g., western and eastern basin boundaries, continental shelf geometry, and other bathymetric features that intercept currents (e.g., islands and sea mounts);

- Sea-ice dynamics;

- Downwelling and upwelling;

- Mixing regime as a function of solar heating, air and sea temperatures, wind stress, surface currents, sea-ice cover, and basin geography and as modified by upwelling and downwelling.

- Ekman transport as above, but with orientations resulting in surface convergence and downwelling (Box 5);

- Surface currents intercepting barriers;

- Density-driven sinking of surface waters, forming intermediate and deep water.

5.1.2. Biomes, Primary Production, and Wind-Driven Circulation Features

- Subtropical gyres (Figure 6)—Productivity in the center of subtropics gyres is nutrient limited. Weak winds associated with subsiding air of overhead Subtropical Highs result in strong, year-round stratification, limiting deep mixing and nutrient availability (Figure 12a). The gyres’ low productivity is indicated by dark blue in Figure 11. The gyres are anticyclonic, driven by easterly Trade Winds near the equator and Mid-latitude Westerlies at their poleward extent (Figure 10). To the east and west, these circulation systems are constrained by ocean basin geography, resulting in eastern and western boundary currents, respectively.

- Downwelling zones—Where strong downwelling of surface water circulates phytoplankton out of the photic zone, productivity becomes light limited. Downwelling also oxygenates otherwise hypoxic deep water, supporting decomposition.

- Western boundary currents—Upwelling replenishes nutrient levels of western boundary currents (Figure 6 and Figure 11). Mentioned earlier, these include the Gulf Stream and Brazil, Agulhas, Kuroshio, and Eastern Australia currents. Upwelling mechanisms include (1) westward equatorial currents intercepting continental margins and (2) Ekman transport driven by poleward winds on the west side of Subtropical Highs [241] (Box 5).

- Equatorial upwelling zones—Equatorial surface currents have relatively high productivity due to the upwelling of nutrient rich water (Figure 6, Figure 11 and Figure 12a). This upwelling is driven by easterly Trade Winds on opposite sides of the equator, resulting in divergence from opposing Ekman processes (Box 5, Figure 2c).

- Subpolar gyres and West Wind Drift currents—North Pacific and North Atlantic Subpolar Gyres are cyclonic, driven by mid-latitude westerly winds to the south and subpolar easterly winds to the north and additionally constrained by ocean basin geography (Figure 6 and Figure 11). These temperate and subpolar waters are highly productive due to nutrients supplied via cold-season wind-driven vertical mixing (Figure 12a and Figure 13a). In spring, algal blooms result from seasonally increasing light levels, in addition to continued nutrient input from mixing. Mixing continues until summer stratification is established. In the Southern Ocean, mid-latitude westerly winds drive the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (West Wind Drift, Figure 6), largely unconstrained by basin geometry. These winds force deep vertical mixing in the winter and spring to depths on the order of 500–1000 m (Figure 13b), supplying nutrients (Figure 12a) supporting high levels of productivity (Figure 11).

- Southern Ocean upwelling zones—Other highly productive regions in the Southern Ocean are upwelling zones near the Antarctic continent (Figure 11). Upwelling occurs (1) in the Antarctic Divergence, (2) where poleward flowing deep water intercepts the continental margin, and (3) along the coast, owing to strong offshore winds originating from the Antarctic interior [245,249]. In the Antarctic Divergence, upwelling is driven by adjacent westerly and easterly winds that result in opposing Ekman transport flows (Box 5, Figure 2d). Upwelling of cold, hypoxic deep-water lowers surface temperatures and decreases dissolved oxygen along the continent (Figure 9b and Figure 12b) and, along with mixing in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, strongly increases nutrient levels in the Southern Ocean (Figure 12a).

- Eastern boundary current upwelling zones—Coastal upwelling zones along western continental margins in the subtropics and mid-latitudes are highly productive. These are primarily along the western coasts of California, Peru, Chile, West Africa, and Namibia (Figure 11) and are associated with corresponding eastern boundary currents—the California, Humboldt, Canary, and Benguela currents. Upwelling is driven by Ekman transport that is forced by equatorward Trade Winds on the east side of the Subtropical Highs (Box 5, Figure 2a,b). These upwelling zones often have a strong signature in maps of nutrient-rich and deoxygenated epipelagic water (Figure 12a,b).

- Continental runoff—High-nutrient continental runoff enhances the productivity of waters offshore river deltas that drain high-precipitation basins. For example, enrichment of nutrient-poor ocean waters by Amazon, Congo, and La Plata (Argentina and Uruguay) rivers is prominent in Figure 11.

5.2. The Thermohaline Circulation

- Wind-driven surface currents;

- Deep-water formation by downwelling of dense surface seawater;

- Deep- and bottom-water currents;

- Upwelling of these deeper waters.

- In the high-latitude North Atlantic, near-surface warm, high-salinity waters of the Gulf Stream become denser with (1) cooling due to heat lost to the atmosphere and (2) increased salinity owing to brine rejection as sea ice forms. In the Nordic and Labrador Seas, this water sinks, forming Atlantic Deep Water (yellow ovals, Figure 14).

- At the surface, these waters flow through the subtropics and tropics where they warm and, owing to high evaporation rates, increase in salinity (green shaded areas in Figure 14). This warm surface return flow is concentrated in the western North Atlantic, forming the Gulf Stream (Figure 6). The circulation then returns to the high-latitude North Atlantic.

5.3. Ocean Carbon Pumps

5.4. Coastal Biomes

6. Changing Climate Dynamics

6.1. Changing Atmospheric Circulation

- On the eastern flanks of the Subtropical Highs, their strengthening has further suppressed precipitation in subtropical deserts. Expansion of the Highs has also broadened the deserts poleward [42,283] and decreased precipitation in adjacent, transitional subtropical–mid-latitude dry climates (e.g., in some Mediterranean-climate regions) [42,284]. Coupled with increased tropical precipitation, these changes have sharpened the wet–dry contrast across lower latitudes [276,285].

- On the western flanks of the Subtropical Highs, east–west shifts in their extent have altered the poleward flow of moisture into adjacent continents, such as in East Asia and southeastern United States [44,286,287,288]. This has altered precipitation regimes of corresponding wet subtropical and warm temperate forests, with regional responses dependent on the nature of the shift [286,287].

- Poleward shifts in the distribution of tropical cyclones (e.g., hurricanes and typhoons) tied to Hadley Circulation expansion [289,290,291,292]. Higher tropical sea surface temperatures and increased water content of the tropical atmosphere over oceans [293,294] have additionally reinforced changes in tropical cyclone storm tracks [291,294].

- An increase in the intensity of mid-latitude and Arctic cyclonic storms. This is in terms of increases in the frequency of stronger storms, storm duration, and precipitation rates and totals [298,299]. Shifts in summertime Arctic Fronts will be moderated by dynamics tying their position to that of the Arctic Ocean and feedbacks with boreal woodlands [130].

6.2. Changing Ocean Dynamics

6.2.1. Physical Regime

- Tropospheric circulation patterns and resulting changes in driving winds;

- Net radiative flux at the surface and sensible and latent heat exchange with the atmosphere, controlling sea surface temperature, evaporation, and seawater freezing (causing brine rejection) and these, in turn, affecting density [308];

- Sea-ice cover limiting these surface energy fluxes [308];

- Freshwater inputs from precipitation, sea-ice melt, continental glacier and ice sheet melt, and continental runoff, affecting seawater salinity [309].

6.2.2. Marine Biome Change Linked to Changing Ocean Climate Dynamics

- Light limitation, with deeper mixing circulating phytoplankton to below the euphotic zone, versus –

- Release from nutrient limitation, with deeper mixing entraining nutrient-rich deeper water into the euphotic zone.

6.2.3. Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) Climate Sensitivity

6.2.4. Coastal Biome Climate Sensitivity

7. Summary and Discussion: Main Lessons for Conservation Planning and Resource Management

7.1. Overview of Earth System Dynamics Driving Biome Distributions

7.1.1. Terrestrial Biomes and Atmospheric Dynamics

7.1.2. Marine Biomes and Ocean Dynamics

7.2. The Dynamics of Change

- Higher temperatures of the troposphere, ocean surface and deep waters, and land and a net loss of sea and land ice, including permafrost;

- Greater potential atmospheric water vapor content resulting from warmer air temperatures;

- Altered global circulation of the atmosphere and oceans.

7.3. Biome and Socioecologic Futures

7.4. Action Under Uncertainty

- Top-down—An impact assessment approach driven “from the top” by global climate model simulations under future socioeconomic scenarios (such as those setting GHG emission pathways). These climate projections may be downscaled by regional climate models (dynamical downscaling) or by statistical methods [376,377,378]. Resulting climate scenarios are subsequently used to drive resource models, including those projecting ecosystem, hydrologic, and socioecological impacts (e.g., [379,380]). These projections can inform planning and decision making at regional and management-unit scales.

- Bottom-up—A vulnerability approach assessing climatic resilience and resistance of “at-the-bottom” resources of concern, such as species, landscapes, seascapes, and ecosystem services [78,381,382]. This is an integrative approach that puts these vulnerabilities in the context of other stressors and focuses on local dynamics [381,383]. Local strategies also need to account for cross-scale interactions that tie local processes to regional threshold dynamics, such as wildfires and desertification [374].

- Scenario planning—Instead of relying on climate and ecological model projections for systems whose complexities are inherently difficult to simulate, scenario planning uses a framework to envision ecological consequences across a spectrum of probable, as well as less probable but still plausible, futures (including conceivable “surprises”). This explores a range of “what if” climate outcomes from those that are moderately to severely disruptive to species and ecosystems [78,388,392]. Scenario planning can also incorporate paleo- and recent ecological histories to put the future in the context of prior system trajectories [79,389,393].

- Least-regrets, win–win, and safe operating space strategies—Actions that in addition to addressing climate vulnerabilities have non-climate related benefits, such as in reducing other environmental threats and promoting socioeconomic well-being [394,395,396]. The reduction of local non-climate stressors (including habitat loss, pollution, and invasive species) works toward keeping systems within their safe operating space in face of difficult-to-control global stressors, such as climate change [30].

- Physical integrity of landscapes—For terrestrial systems, a focus on the maintenance and restoration of physical landscape attributes (e.g., connectivity and hydrologic function) to provide for (1) the movement of species when habitats change and (2) the development of intact ecological and evolutionary processes following extreme climate disruption, regardless of what ecosystems may arise there [397,398,399].

- Adaptive management and adaptive pathway planning—Adaptive management emphasizes reactive flexibility, relying on monitoring and periodic reassessment to adjust strategies in response to observed changes and new knowledge [389,400,401,402]. Complementary to this, adaptive pathway planning is proactively anticipatory, preparing for multiple ecological trajectories and establishing contingency plans to shift strategies as the future unfolds [389,403].

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Glossary

References

- von Schuckmann, K.; Minière, A.; Gues, F.; Cuesta-Valero, F.J.; Kirchengast, G.; Adusumilli, S.; Straneo, F.; Ablain, M.; Allan, R.P.; Barker, P.M.; et al. Heat stored in the Earth system 1960–2020: Where does the energy go? Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 1675–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R.A.; Peters, D.P.C.; Niyogi, D. Ecology and climate of the Earth—The same biogeophysical system. Climate 2022, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, I.C. Interactions of Climate Change and the Terrestrial Biosphere. In Geosphere-Biosphere Interactions and Climate; Bengtsson, L.O., Hammer, C.U., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 176–196. ISBN 9780521782388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneth, A.; Harrison, S.P.; Zaehle, S.; Tsigaridis, K.; Menon, S.; Bartlein, P.J.; Feichter, J.; Korhola, A.; Kulmala, M.; O’Donnell, D.; et al. Terrestrial biogeochemical feedbacks in the climate system. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, J.E.; Margulis, L. Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: The gaia hypothesis. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 1974, 26, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, J. Gaia: The living Earth. Nature 2003, 426, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, S.; Crucifix, M. Taking the Gaia hypothesis at face value. Ecol. Complex. 2022, 49, 100981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isson, T.T.; Planavsky, N.J.; Coogan, L.A.; Stewart, E.M.; Ague, J.J.; Bolton, E.W.; Zhang, S.; McKenzie, N.R.; Kump, L.R. Evolution of the Global Carbon Cycle and Climate Regulation on Earth. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2020, 34, e2018GB006061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Bond, W.J. Feedbacks in ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022, 37, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Randerson, J.T.; McGuire, A.D.; Foley, J.A.; Field, C.B. Changing feedbacks in the climate–biosphere system. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 6, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Lenton, T.M.; Gregg, J.W.; Natali, S.M.; Duffy, P.B.; Rockström, J.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Many risky feedback loops amplify the need for climate action. One Earth 2023, 6, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2006, 37, 637–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adelekan, I.; Adler, C.; Adrian, R.; Aldunce, P.; Ali, E.; Ara Begum, R.; Bednar-Friedl, B.; et al. Technical Summary (IPCC WGII AR6). In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskopf, S.R.; Rubenstein, M.A.; Crozier, L.G.; Gaichas, S.; Griffis, R.; Halofsky, J.E.; Hyde, K.J.W.; Morelli, T.L.; Morisette, J.T.; Munoz, R.C.; et al. Climate change effects on biodiversity, ecosystems, ecosystem services, and natural resource management in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 733, 137782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffers, B.R.; De Meester, L.; Bridge, T.C.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Pandolfi, J.M.; Corlett, R.T.; Butchart, S.H.; Pearce-Kelly, P.; Kovacs, K.M.; Dudgeon, D.; et al. The broad footprint of climate change from genes to biomes to people. Science 2016, 354, aaf7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C.; Hanley, M.E. Plants and climate change: Complexities and surprises. Ann. Bot. 2015, 116, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Gregg, J.W.; Rockström, J.; Mann, M.E.; Oreskes, N.; Lenton, T.M.; Rahmstorf, S.; Newsome, T.M.; Xu, C.; et al. The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times on planet Earth. Bioscience 2024, 74, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Mann, M.E.; Rockström, J.; Gregg, J.W.; Xu, C.; Wunderling, N.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E.; Schaeffer, R.; Broadgate, W.J.; et al. The 2025 state of the climate report: A planet on the brink. Bioscience 2025, 75, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R.A.; Pitman, A.; Niyogi, D.; Mahmood, R.; McAlpine, C.; Hossain, F.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Nair, U.; Betts, R.; Fall, S.; et al. Land use/land cover changes and climate: Modeling analysis and observational evidence. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2011, 2, 828–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulev, S.K.; Thorne, P.W.; Ahn, J.; Dentener, F.J.; Domingues, C.M.; Gerland, S.; Gong, D.; Kaufman, D.S.; Nnamchi, H.C.; Quaas, J.; et al. Changing State of the Climate System. Chapter 2. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC WGI); Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, New York, NY, USA; 2021; pp. 287–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, P.A.; Bellouin, N.; Coppola, E.; Jones, R.G.; Krinner, G.; Marotzke, J.; Naik, V.; Palmer, M.D.; Plattner, G.-K.; Rogelj, J.; et al. Technical Summary (IPCC WGI AR6). In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, New York, NY, USA; 2021; pp. 33–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, J.A.; Pielke, R.A.; Beniston, M.; Claussen, M.; Canadell, J.; Cox, P.; Held, H.; de Noblet-Ducoudré, N.; Prinn, R.; Reynolds, J.F.; et al. Nonlinearities, feedbacks and critical thresholds within the Earth’s climate system. Clim. Change 2004, 65, 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, I.; Armour, K.C. The radiative feedback continuum from Snowball Earth to an ice-free hothouse. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milly, P.C.; Betancourt, J.; Falkenmark, M.; Hirsch, R.M.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Stouffer, R.J. Climate change. Stationarity Is Dead: Whither Water Management? Science 2008, 319, 573–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Rockstrom, J.; Richardson, K.; Lenton, T.M.; Folke, C.; Liverman, D.; Summerhayes, C.P.; Barnosky, A.D.; Cornell, S.E.; Crucifix, M.; et al. Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8252–8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, C.; Mahecha, M.D.; Frank, D.C.; Babst, F.; Koutsoyiannis, D. Ecosystem functioning is enveloped by hydrometeorological variability. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, R.; Spies, T.A.; Peterson, D.L.; Stephens, S.L.; Hicke, J.A. Searching for resilience: Addressing the impacts of changing disturbance regimes on forest ecosystem services. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetnam, T.W.; Allen, C.D.; Betancourt, J.L. Applied Historical Ecology: Using the Past to Manage for the Future. Ecol. Appl. 1999, 9, 1189–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.; Aplet, G.H.; Haufler, J.B.; Humphries, H.C.; Moore, M.M.; Wilson, W.D. Historical range of variability. A useful tool for evaluating ecosystem change. J. Sustain. For. 1994, 2, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Barrett, S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Folke, C.; Green, A.J.; Holmgren, M.; Hughes, T.P.; Kosten, S.; van de Leemput, I.A.; Nepstad, D.C.; et al. Climate and conservation. Creating a safe operating space for iconic ecosystems. Science 2015, 347, 1317–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Born, A. Coupled atmosphere-ice-ocean dynamics in Dansgaard-Oeschger events. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 203, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Garzón, M.; Leadley, P.W.; Fernández-Manjarrés, J.F. Assessing global biome exposure to climate change through the Holocene–Anthropocene transition. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 23, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.T.; Overpeck, J.T. Responses of plant populations and communities to environmental changes of the late Quaternary. Paleobiology 2000, 26, 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semken, H.A.; Graham, R.W.; Stafford, T.W. AMS 14C analysis of Late Pleistocene non-analog faunal components from 21 cave deposits in southeastern North America. Quat. Int. 2010, 217, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.W.; Jackson, S.T. Novel climates, no-analog communities, and ecological surprises. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büntgen, U.; Myglan, V.S.; Ljungqvist, F.C.; McCormick, M.; Di Cosmo, N.; Sigl, M.; Jungclaus, J.; Wagner, S.; Krusic, P.J.; Esper, J.; et al. Cooling and societal change during the Late Antique Little Ice Age from 536 to around 660 AD. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Schulz, M.; Abe-Ouchi, A.; Beer, J.; Ganopolski, A.; González Rouco, J.F.; Jansen, E.; Lambeck, K.; Luterbacher, J.; Naish, T.; et al. Information from Paleoclimate Archives. Chapter 5. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 383–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, V.; Stríkis, N.M.; Santos, R.A.; De Souza, J.G.; Ampuero, A.; Cruz, F.W.; De Oliveira, P.; Iriarte, J.; Stumpf, C.F.; Vuille, M.; et al. Medieval Climate Variability in the eastern Amazon-Cerrado regions and its archeological implications. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, J.; Torbenson, M.; Buntgen, U. 2023 summer warmth unparalleled over the past 2000 years. Nature 2024, 631, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esper, J.; Smerdon, J.E.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; Allen, K.; Cook, E.R.; D’Arrigo, R.; Guillet, S.; Ljungqvist, F.C.; Reinig, F.; Schneider, L.; et al. The IPCC’s reductive Common Era temperature history. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Singh, D.; Mankin, J.S.; Horton, D.E.; Swain, D.L.; Touma, D.; Charland, A.; Liu, Y.; Haugen, M.; Tsiang, M.; et al. Quantifying the influence of global warming on unprecedented extreme climate events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4881–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell-Clay, N.; Ummenhofer, C.C.; Thatcher, D.L.; Wanamaker, A.D.; Denniston, R.F.; Asmerom, Y.; Polyak, V.J. Twentieth-century Azores High expansion unprecedented in the past 1,200 years. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeter, K.J.; Harley, G.L.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; Cook, E.R.; Coulthard, B.L.; Dye, L.A.; Homfeld, I.K. Unprecedented 21st century heat across the Pacific Northwest of North America. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregy, J.C.; Maxwell, J.T.; Robeson, S.M.; Harley, G.L.; Trouet, V. Changes in the western flank of the North Atlantic subtropical high since 1140 CE: Extremes, drivers, and hydroclimatic patterns. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spooner, P.T.; Thornalley, D.J.R.; Oppo, D.W.; Fox, A.D.; Radionovskaya, S.; Rose, N.L.; Mallett, R.; Cooper, E.; Roberts, J.M. Exceptional 20th Century Ocean Circulation in the Northeast Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL087577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, L.; McCarthy, G.D.; Thornalley, D.J.R.; Cahill, N.; Rahmstorf, S. Current Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation weakest in last millennium. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S.; Timmermann, A.; England, M.H.; Elison Timm, O.; Wittenberg, A.T. Inferred changes in El Niño–Southern Oscillation variance over the past six centuries. Clim. Past 2013, 9, 2269–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, S.C.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Duffy, J.E.; Barry, J.P.; Chan, F.; English, C.A.; Galindo, H.M.; Grebmeier, J.M.; Hollowed, A.B.; Knowlton, N.; et al. Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012, 4, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmesan, C.; Yohe, G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 2003, 421, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; O’Connor, M.I.; Poloczanska, E.S.; Schoeman, D.S.; Buckley, L.B.; Burrows, M.T.; Duarte, C.M.; Halpern, B.S.; Pandolfi, J.M.; Parmesan, C.; et al. Ecological and methodological drivers of species’ distribution and phenology responses to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 1548–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecl, G.T.; Araújo, M.B.; Bell, J.D.; Blanchard, J.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Chen, I.-C.; Clark, T.D.; Colwell, R.K.; Danielsen, F.; Evengård, B.; et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 2017, 355, eaai9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.E. Keeping up with a warming world; assessing the rate of adaptation to climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 275, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.W.; Schindler, D.E. Getting ahead of climate change for ecological adaptation and resilience. Science 2022, 376, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noss, R.F. Indicators for Monitoring Biodiversity: A Hierarchical Approach. Conserv. Biol. 1990, 4, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Gupta, J.; Qin, D.; Lade, S.J.; Abrams, J.F.; Andersen, L.S.; Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Bai, X.; Bala, G.; Bunn, S.E.; et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 2023, 619, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, D.M.; Wienecke, B.C.; Van Den Hoff, J.; Hughes, L.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Ainsworth, T.D.; Baker, C.M.; Bland, L.; Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Brooks, S.T.; et al. Combating ecosystem collapse from the tropics to the Antarctic. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1692–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, D.; Bennett, J.S.; Reddish, J.; Holder, S.; Howard, R.; Benam, M.; Levine, J.; Ludlow, F.; Feinman, G.; Turchin, P. Navigating polycrisis: Long-run socio-cultural factors shape response to changing climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portner, H.O.; Scholes, R.J.; Arneth, A.; Barnes, D.K.A.; Burrows, M.T.; Diamond, S.E.; Duarte, C.M.; Kiessling, W.; Leadley, P.; Managi, S.; et al. Overcoming the coupled climate and biodiversity crises and their societal impacts. Science 2023, 380, eabl4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, D.; Mintz-Woo, K.; Desroches, C.T. Collapse, social tipping dynamics, and framing climate change. Politics Philos. Econ. 2024, 23, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, T.M.; Rockstrom, J.; Gaffney, O.; Rahmstorf, S.; Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Climate tipping points—Too risky to bet against. Nature 2019, 575, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Lucht, W.; Bendtsen, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Donges, J.F.; Druke, M.; Fetzer, I.; Bala, G.; von Bloh, W.; et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, C.; Dakos, V.; Ritchie, P.D.L.; Sillmann, J.; Rocha, J.C.; Milkoreit, M.; Quinn, C. Earth system resilience and tipping behavior. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 070201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Brecke, P.; Lee, H.F.; He, Y.-Q.; Zhang, J. Global climate change, war, and population decline in recent human history. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19214–19219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Lee, H.F.; Wang, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Pei, Q.; Chen, J. Climate change and large-scale human population collapses in the pre-industrial era. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukom, R.; Steiger, N.; Gómez-Navarro, J.J.; Wang, J.; Werner, J.P. No evidence for globally coherent warm and cold periods over the preindustrial Common Era. Nature 2019, 571, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, H.S.; Feely, R.A.; Jiang, L.Q.; Pelletier, G.; Bednarsek, N. Ocean Acidification: Another Planetary Boundary Crossed. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Field, C.B. Changes in Ecologically Critical Terrestrial Climate Conditions. Science 2013, 341, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overpeck, J.T.; Webb, R.S.; Webb, T. Mapping eastern North American vegetation change of the past 18 ka: No-analogs and the future. Geology 1992, 20, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graumlich, L.J. Long-term vegetation change in mountain environments: Palaeoecological insights into modern vegetation dynamics. Chapter 10. In Mountain Environments in Changing Climates; Beniston, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 167–179, ISBN 9780203424957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Nicolai, M., Okem, A., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, New York, NY, USA; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, C.L.; McKay, N.P.; Erb, M.P.; Kaufman, D.S.; Routson, C.R.; Ivanovic, R.F.; Gregoire, L.J.; Valdes, P. Global Synthesis of Regional Holocene Hydroclimate Variability Using Proxy and Model Data. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol 2023, 38, e2022PA004597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Spötl, C.; Baker, J.; Sinha, A.; Li, H.; Bartolomé, M.; Moreno, A.; Kathayat, G.; Zhao, J.; et al. Timing and structure of the Younger Dryas event and its underlying climate dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 23408–23417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppä, H.; Birks, H.H.; Birks, H.J.B. Rapid climatic changes during the Greenland stadial 1 (Younger Dryas) to early Holocene transition on the Norwegian Barents Sea coast. Boreas 2002, 31, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partin, J.W.; Quinn, T.M.; Shen, C.C.; Okumura, Y.; Cardenas, M.B.; Siringan, F.P.; Banner, J.L.; Lin, K.; Hu, H.M.; Taylor, F.W. Gradual onset and recovery of the Younger Dryas abrupt climate event in the tropics. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buizert, C.; Sigl, M.; Severi, M.; Markle, B.R.; Wettstein, J.J.; McConnell, J.R.; Pedro, J.B.; Sodemann, H.; Goto-Azuma, K.; Kawamura, K.; et al. Abrupt ice-age shifts in southern westerly winds and Antarctic climate forced from the north. Nature 2018, 563, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markle, B.R.; Steig, E.J.; Buizert, C.; Schoenemann, S.W.; Bitz, C.M.; Fudge, T.J.; Pedro, J.B.; Ding, Q.; Jones, T.R.; White, J.W.C.; et al. Global atmospheric teleconnections during Dansgaard–Oeschger events. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, T.M.; Held, H.; Kriegler, E.; Hall, J.W.; Lucht, W.; Rahmstorf, S.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, T.G.F. The Vulnerability of Biodiversity to Rapid Climate Change. Chapter 4.15. In Vulnerability of Ecosystems to Climate; Seastedt, T.R., Suding, K., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 185–201. ISBN 978-0-12-384704-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.W.; Jackson, S.T.; Kutzbach, J.E. Projected distributions of novel and disappearing climates by 2100 AD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5738–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.E. Climate of the Arctic marine environment. Ecol. Appl. 2008, 18, S3–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, L.J.; Pitman, A.; Perkins, S.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Yoccoz, N.G.; Thuiller, W. Impacts of climate change on the world’s most exceptional ecoregions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2306–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyer, C.P.O.; Leuzinger, S.; Rammig, A.; Wolf, A.; Bartholomeus, R.P.; Bonfante, A.; De Lorenzi, F.; Dury, M.; Gloning, P.; Abou Jaoudé, R.; et al. A plant’s perspective of extremes: Terrestrial plant responses to changing climatic variability. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Carpenter, S.; Foley, J.A.; Folke, C.; Walker, B. Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature 2001, 413, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trisos, C.H.; Merow, C.; Pigot, A.L. The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change. Nature 2020, 580, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M.; Kumar, D.; Martens, C.; Scheiter, S. Climate change will cause non-analog vegetation states in Africa and commit vegetation to long-term change. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 5829–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, M.C.; Tewksbury, J.J.; Sheldon, K.S. On a collision course: Competition and dispersal differences create no-analogue communities and cause extinctions during climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 279, 2072–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descombes, P.; Pitteloud, C.; Glauser, G.; Defossez, E.; Kergunteuil, A.; Allard, P.M.; Rasmann, S.; Pellissier, L. Novel trophic interactions under climate change promote alpine plant coexistence. Science 2020, 370, 1469–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ålund, M.; Cenzer, M.; Bierne, N.; Boughman, J.W.; Cerca, J.; Comerford, M.S.; Culicchi, A.; Langerhans, B.; McFarlane, S.E.; Most, M.H.; et al. Anthropogenic Change and the Process of Speciation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2023, 15, a041455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R.J.; Arico, S.; Aronson, J.; Baron, J.S.; Bridgewater, P.; Cramer, V.A.; Epstein, P.R.; Ewel, J.J.; Klink, C.A.; Lugo, A.E.; et al. Novel ecosystems: Theoretical and management aspects of the new ecological world order. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2006, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, S.E.; Urban, M.C.; Tewksbury, J.; Gilchrist, G.W.; Holt, R.D. A framework for community interactions under climate change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.C.; Parmesan, C. Phenological asynchrony between herbivorous insects and their hosts: Signal of climate change or pre-existing adaptive strategy? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3161–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeley, K.J.; Bravo-Avila, C.; Fadrique, B.; Perez, T.M.; Zuleta, D. Climate-driven changes in the composition of New World plant communities. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Miller, J.E.D.; Harrison, S. Climate drives loss of phylogenetic diversity in a grassland community. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19989–19994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernberg, T.; Bennett, S.; Babcock, R.C.; de Bettignies, T.; Cure, K.; Depczynski, M.; Dufois, F.; Fromont, J.; Fulton, C.J.; Hovey, R.K.; et al. Climate-driven regime shift of a temperate marine ecosystem. Science 2016, 353, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, P.S.A.; Juday, G.P.; Alix, C.; Barber, V.A.; Winslow, S.E.; Sousa, E.E.; Heiser, P.; Herriges, J.D.; Goetz, S.J. Changes in forest productivity across Alaska consistent with biome shift. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, K.J.; Emery, N.C. Managing Microevolution: Restoration in the Face of Global Change. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A.; Larson, E.L.; Harrison, R.G. Hybrid zones: Windows on climate change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryding, S.; Klaassen, M.; Tattersall, G.J.; Gardner, J.L.; Symonds, M.R.E. Shape-shifting: Changing animal morphologies as a response to climatic warming. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 1036–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peers, M.J.; Wehtje, M.; Thornton, D.H.; Murray, D.L. Prey switching as a means of enhancing persistence in predators at the trailing southern edge. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E.; Sato, M.; Simons, L.; Nazarenko, L.S.; Sangha, I.; Kharecha, P.; Zachos, J.C.; von Schuckmann, K.; Loeb, N.G.; Osman, M.B.; et al. Global warming in the pipeline. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 2023, 3, kgad008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Marotzke, J.; Bala, G.; Cao, L.; Corti, S.; Dunne, J.P.; Engelbrecht, F.; Fischer, E.; Fyfe, J.C.; Jones, C.; et al. Future Global Climate: Scenario-Based Projections and Near-Term Information. Chapter 4. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, New York, NY, USA; 2021; pp. 553–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rummukainen, M. Our commitment to climate change is dependent on past, present and future emissions and decisions. Clim. Res. 2015, 64, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.D.; Weaver, A.J. Committed climate warming. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 142–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.R.; Friedlingstein, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Jenkins, S.; Malhi, Y.; Mitchell-Larson, E.; Peters, G.P.; Rajamani, L. Net Zero: Science, Origins, and Implications. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 849–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo Corner, S.; Siegert, M.; Ceppi, P.; Fox-Kemper, B.; Frölicher, T.L.; Gallego-Sala, A.; Haigh, J.; Hegerl, G.C.; Jones, C.D.; Knutti, R.; et al. The Zero Emissions Commitment and climate stabilization. Front. Sci. 2023, 1, 1170744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, A.H.; Frölicher, T.L.; Jones, C.D.; Rogelj, J.; Matthews, H.D.; Zickfeld, K.; Arora, V.K.; Barrett, N.J.; Brovkin, V.; Burger, F.A.; et al. Is there warming in the pipeline? A multi-model analysis of the Zero Emissions Commitment from CO2. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 2987–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, P.; Williams, R.G.; Ridgwell, A. Sensitivity of climate to cumulative carbon emissions due to compensation of ocean heat and carbon uptake. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; Schaeffer, R.; Arango, J.; Calvin, K.; Guivarch, C.; Hasegawa, T.; Jiang, K.; Kriegler, E.; Matthews, R.; Peters, G.P.; et al. Mitigation pathways compatible with long-term goals. Chapter 3. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC WGIII); Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, M.; Reichstein, M. Terrestrial ecosystem carbon dynamics and climate feedbacks. Nature 2008, 451, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.G.; Brewer, P.G.; Oschlies, A.; Watson, A.J. Ocean ventilation and deoxygenation in a warming world: Introduction and overview. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375, 20170240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, A.H.; Mallett, J.; Hohn, D.; Mengis, N. Substantial regional climate change expected following cessation of CO2 emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 114046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L.J.; King, A.D.; Brown, J.R.; MacDougall, A.H.; Ziehn, T.; Min, S.-K.; Jones, C.D. Regional temperature extremes and vulnerability under net zero CO2 emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 014051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, J.F.; Huntingford, C.; Williamson, M.S.; Armstrong Mckay, D.I.; Boulton, C.A.; Buxton, J.E.; Sakschewski, B.; Loriani, S.; Zimm, C.; Winkelmann, R.; et al. Committed Global Warming Risks Triggering Multiple Climate Tipping Points. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2022EF003250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Bascompte, J.; Brock, W.A.; Brovkin, V.; Carpenter, S.R.; Dakos, V.; Held, H.; van Nes, E.H.; Rietkerk, M.; Sugihara, G. Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature 2009, 461, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, T.; Högner, A.E.; Schleussner, C.F.; Bien, S.; Kitzmann, N.H.; Lamboll, R.D.; Rogelj, J.; Donges, J.F.; Rockstrom, J.; Wunderling, N. Achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions critical to limit climate tipping risks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimori, S.; Nishiura, O.; Oshiro, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Shiraki, H.; Shiogama, H.; Takahashi, K.; Takakura, J.Y.; Tsuchiya, K.; Sugiyama, M.; et al. Reconsidering the lower end of long-term climate scenarios. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Plattner, G.K.; Knutti, R.; Friedlingstein, P. Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengel, M.; Nauels, A.; Rogelj, J.; Schleussner, C.-F. Committed sea-level rise under the Paris Agreement and the legacy of delayed mitigation action. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourn, G.; Ridgwell, A.; Lenton, T.M. The time scale of the silicate weathering negative feedback on atmospheric CO2. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2015, 29, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.S.; O’Neill, M.E. Thermodynamics of the climate system. Phys. Today 2022, 75, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Lembo, V.; Franzke, C.L.E. The Lorenz energy cycle: Trends and the impact of modes of climate variability. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2021, 73, 1900033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lohmann, G.; Krebs-Kanzow, U.; Ionita, M.; Shi, X.; Sidorenko, D.; Gong, X.; Chen, X.; Gowan, E.J. Poleward Shift of the Major Ocean Gyres Detected in a Warming Climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL085868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, P. 8.1 Earth’s Heat Budget. In PPSC GEY 1155 Introduction to Oceanography: Pressbooks. 2021. Available online: https://pressbooks.ccconline.org/introduction-to-oceanography/chapter/8-1-earths-heat-budget/ (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Barry, R.G.; Chorley, R.J. Atmosphere, Weather and Climate, 9th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780203871027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgens, F.K.; Tarbuck, E.J.; Herman, R. The Atmosphere: An Introduction to Meteorology, 14th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 528. ISBN 9780135213148. [Google Scholar]

- Palmén, E. The rôle of atmospheric disturbances in the general circulation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1951, 77, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, R.A. Air Masses, Streamlines and the Boreal Forest. Geogr. Bull. 1966, 8, 228–269. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, R.G. Seasonal location of the Arctic front over North America. Geogr. Bull. 1967, 9, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pielke, R.A.; Vidale, P.L. The boreal forest and the polar front. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1995, 100, 25755–25758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, F.K.; Ritchie, J.C. The Boreal Bioclimates. Geogr. Rev. 1972, 62, 333–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.L. The Regionalization of Climate in the Western United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1976, 15, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, R.P.; Wullstein, L.H. Biogeography of Two Southwest American Oaks in Relation to Atmospheric Dynamics. J. Biogeogr. 1983, 10, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.A. Upper Atmospheric Controls, Surface Climate, and Phytogeographical Implications in the Western Great Lakes Region. Ph.D. Theis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.A.; Harman, J.R. Climate and Vegetation in Central North America: Natural Patterns and Human Alterations. In Conservation of Great Plains Ecosystems: Current Science, Future Options; Johnson, S.R., Bouzaher, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 135–148. ISBN 978-94-011-0439-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; McElroy, M.B. Contributions of the Hadley and Ferrel Circulations to the Energetics of the Atmosphere over the Past 32 Years. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 2656–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E.; Stepaniak, D.P. Covariability of components of poleward atmospheric energy transports on seasonal and interannual timescales. J. Clim. 2003, 16, 3691–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, J.T.; Trenberth, K.E. The annual cycle of the energy budget. Part II: Meridional structures and poleward transports. J. Clim. 2008, 21, 2313–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, A.; Biasutti, M.; Scheff, J.; Bader, J.; Bordoni, S.; Codron, F.; Dixon, R.D.; Jonas, J.; Kang, S.M.; Klingaman, N.P.; et al. The tropical rain belts with an annual cycle and a continent model intercomparison project: TRACMIP. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2016, 8, 1868–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lohmann, G.; Shi, X.; Li, C. Enhanced Mid-Latitude Meridional Heat Imbalance Induced by the Ocean. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E.; Stepaniak, D.P. Seamless Poleward Atmospheric Energy Transports and Implications for the Hadley Circulation. J. Clim. 2003, 16, 3706–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreze, M.C.; Lynch, A.H.; Clark, M.P. The Arctic Frontal Zone as Seen in the NCEP–NCAR Reanalysis. J. Clim. 2001, 14, 1550–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Serreze, M. A New Look at the Summer Arctic Frontal Zone. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreze, M.C.; Barrett, A.P.; Slater, A.G.; Steele, M.; Zhang, J.; Trenberth, K.E. The large-scale energy budget of the Arctic. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D11122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuecker, M.F. The climate variability trio: Stochastic fluctuations, El Niño, and the seasonal cycle. Geosci. Lett. 2023, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robock, A. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 2000, 38, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, I. Major Modes of Variability. Chapter 2. In Climate Variability and Sunspot Activity: Analysis of the Solar Influence on Climate; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, I. (Ed.) Climate Variability and Sunspot Activity; Springer Atmospheric Sciences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, H. Vegetation of the Earth and Ecological Systems of the Geo-Biosphere, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; ISBN 9783642968594. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, R.H. Communities and Ecosystems, 2nd ed.; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1975; p. 385. ISBN 978-0024273901. [Google Scholar]

- Holdridge, L.R.; Grenke, W.C.; Hatheway, W.H.; Liang, T.; Tosi, J.A., Jr. Forest Environments in Tropical Life Zones: A Pilot Study; Oxford Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1971; p. 747. ISBN 0080163408. [Google Scholar]

- Holdridge, L.R. Determination of World Plant Formations From Simple Climatic Data. Science 1947, 105, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, C.W. An Approach toward a Rational Classification of Climate. Geogr. Rev. 1948, 38, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseth, N.C.; Mysterud, A. Weather packages: Finding the right scale and composition of climate in ecology. J. Anim. Ecol. 2005, 74, 1195–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, L.T.; Humphreys, A.M. Global variation in the thermal tolerances of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13580–13587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, D.P.C.; Savoy, H.M.; Stillman, S.; Huang, H.; Hudson, A.R.; Sala, O.E.; Vivoni, E.R. Plant Species Richness in Multiyear Wet and Dry Periods in the Chihuahuan Desert. Climate 2021, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumou, D.; Lehmann, J.; Beckmann, J. The weakening summer circulation in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes. Science 2015, 348, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R. Species Distribution Models: Ecological Explanation and Prediction Across Space and Time. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009, 40, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.A.; Stralberg, D.; Jongsomjit, D.; Howell, C.A.; Snyder, M.A. Niches, models, and climate change: Assessing the assumptions and uncertainties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19729–19736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.J.; White, M.D.; Newell, G.R. How useful are species distribution models for managing biodiversity under future climates? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, D.W. Climate change and phenology. WIREs Clim. Change 2022, 13, e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, J.M.; Bates, A.E.; Dulvy, N.K. Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Barley, J.M.; Gignoux-Wolfsohn, S.; Hays, C.G.; Kelly, M.W.; Putnam, A.B.; Sheth, S.N.; Villeneuve, A.R.; Cheng, B.S. Greater evolutionary divergence of thermal limits within marine than terrestrial species. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewksbury, J.J.; Huey, R.B.; Deutsch, C.A. Putting the Heat on Tropical Animals. Science 2008, 320, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillman, J.H. Acclimation Capacity Underlies Susceptibility to Climate Change. Science 2003, 301, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Putten, W.H.; Macel, M.; Visser, M.E. Predicting species distribution and abundance responses to climate change: Why it is essential to include biotic interactions across trophic levels. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2025–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffress, M.R.; Rodhouse, T.J.; Ray, C.; Wolff, S.; Epps, C.W. The idiosyncrasies of place: Geographic variation in the climate–distribution relationships of the American pika. Ecol. Appl. 2013, 23, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, E.A.; Iknayan, K.J.; Hargrove, L.; Tremor, S.; Patton, J.L.; Ramirez, R.; Wolf, B.O.; Beissinger, S.R. Exposure to climate change drives stability or collapse of desert mammal and bird communities. Science 2021, 371, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenning, J.C.; Sandel, B. Disequilibrium vegetation dynamics under future climate change. Am. J. Bot. 2013, 100, 1266–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, F.; Eldridge, D.J.; Garcia, C.; Kenny Png, G.; Bardgett, R.D.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Soil microbial diversity-biomass relationships are driven by soil carbon content across global biomes. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.M.; Shugart, H.H.; Woodward, F.I. (Eds.) Plant Functional Types: Their Relevance to Ecosystem Properties and Global Change; International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme Book Series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; Volume 1, ISBN 9780521566438. [Google Scholar]

- Running, S.W.; Nemani, R.R.; Heinsch, F.A.; Zhao, M.; Reeves, M.; Hashimoto, H. A Continuous Satellite-Derived Measure of Global Terrestrial Primary Production. Bioscience 2004, 54, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, T.G.F. The Distribution of Vegetation in North America With Respect to Tropospheric Circulation Parameters. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Davis, CA, USA, 1986. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.x34468 (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Neilson, R.P. Biotic regionalization and climatic controls in western North America. Vegetatio 1987, 70, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Matson, P.A.; Vitousek, P.M. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology, 2nd ed; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-9504-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]