The Perceptions of Rural Australians Concerning the Health Impacts of Extreme Weather Events: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Process

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

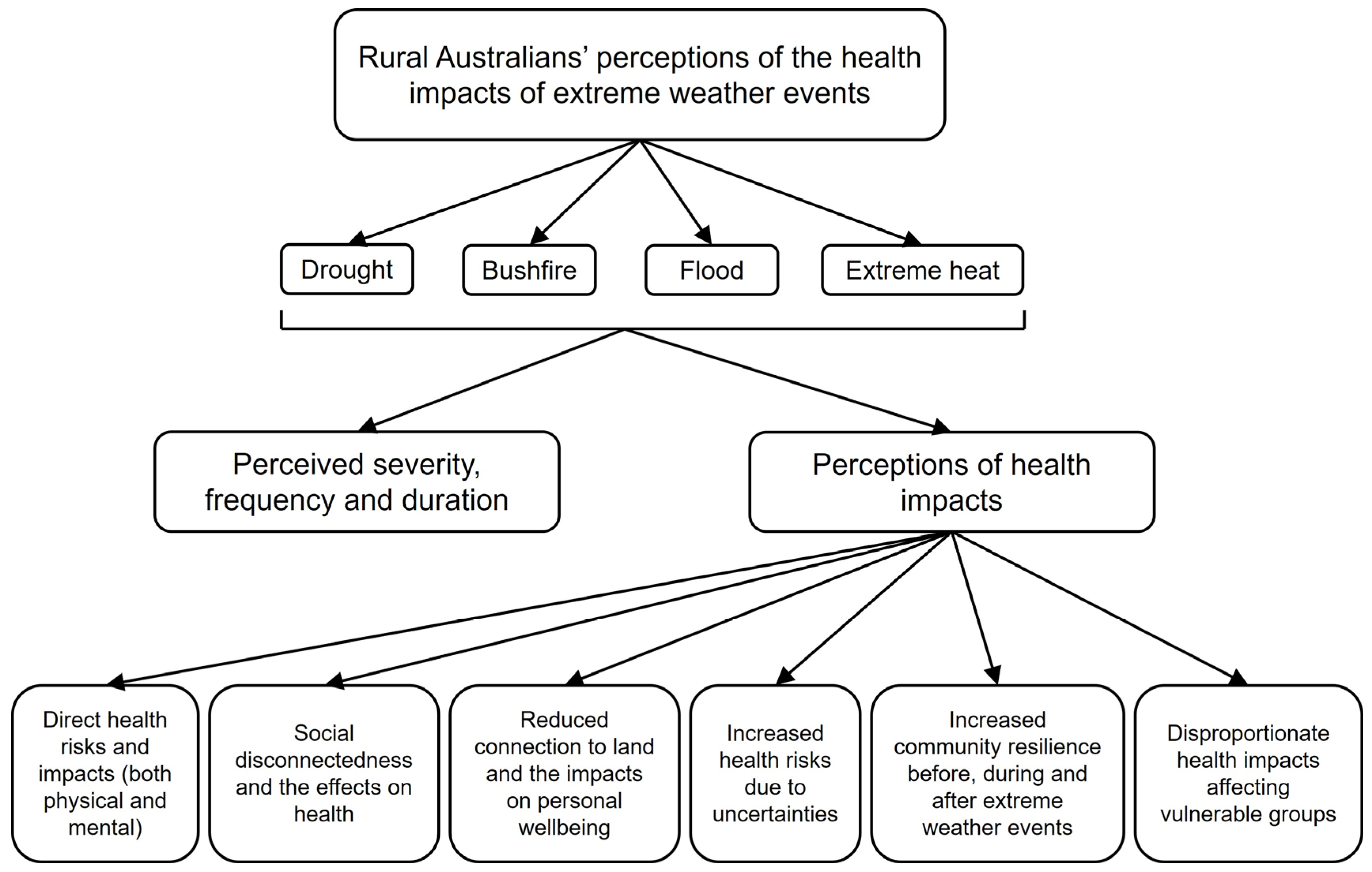

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. Perceived Severity, Frequency and Duration of Extreme Weather Events

3.3. Perceptions of Health Impacts

3.3.1. Direct Health Risks and Impacts (Both Physical and Mental)

3.3.2. Social Disconnectedness and the Effects on Health

3.3.3. Reduced Connection to Land and the Impacts on Personal Wellbeing

3.3.4. Increased Health Risks Due to Uncertainties

3.3.5. Increased Community Resilience Before, During and After Extreme Weather Events

3.3.6. Disproportionate Health Impacts Affecting Vulnerable Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Findings

4.2. Wide-Ranging Mental Health Concerns

4.3. Social Disconnection and Resilience

4.4. Evidence Gaps

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| PICo | Population, phenomena of interest, context |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| NSW | New South Wales |

| Vic | Victoria |

| SA | South Australia |

| Qld | Queensland |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

References

- Ebi, K.L.; Vanos, J.; Baldwin, J.W.; Bell, J.E.; Hondula, D.M.; Errett, N.A.; Hayes, K.; Reid, C.E.; Saha, S.; Spector, J.; et al. Extreme Weather and Climate Change: Population Health and Health System Implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oldenborgh, G.J.; Krikken, F.; Lewis, S.; Leach, N.J.; Lehner, F.; Saunders, K.R.; Van Weele, M.; Haustein, K.; Li, S.; Wallom, D.; et al. Attribution of the Australian bushfire risk to anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, K.; Blashki, G.; Wiseman, J.; Burke, S.; Reifels, L. Climate change and mental health: Risks, impacts and priority actions. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.; Kokic, P.; Crimp, S.; Martin, P.; Meinke, H.; Howden, S.M.; de Voil, P.; Nidumolu, U. The vulnerability of Australian rural communities to climate variability and change: Part II—Integrating impacts with adaptive capacity. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, V.; Longman, J.; Berry, H.L.; Passey, M.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Morgan, G.G.; Pit, S.; Rolfe, M.; Bailie, R.S. Differential Mental Health Impact Six Months After Extensive River Flooding in Rural Australia: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Through an Equity Lens. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Group. Rural Population (% of Total Population). 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?end=2023&start=1960&view=chart (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Bailie, R. Climate-Related Natural Disasters: Reflections on an Agenda for Rural Health Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavel, J.; Kedzior, S.G.; Isaac, V.; Cameron, D.; Baum, F. Regional health inequalities in Australia and social determinants of health: Analysis of trends and distribution by remoteness. Rural Remote Health 2024, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and Remote Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Beard, J.R.; Tomaska, N.; Earnest, A.; Summerhayes, R.; Morgan, G. Influence of socioeconomic and cultural factors on rural health. Aust. J. Rural Health 2009, 17, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, S.P.; Kasim, R.; Sutarsa, I.N.; Hunter, A.; Dykgraaf, S.H. Effects of climate-related risks and extreme events on health outcomes and health utilization of primary care in rural and remote areas: A scoping review. Fam. Pract. 2023, 40, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, P.; Parton, K.A. Effect of climate change on Australian rural and remote regions: What do we know and what do we need to know? Aust. J. Rural Health 2008, 16, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.; Pereira, G.; Uhl, S.A.; Bravo, M.A.; Bell, M.L. A systematic review of the physical health impacts from non-occupational exposure to wildfire smoke. Environ. Res. 2015, 136, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello, M.; Di Napoli, C.; Drummond, P.; Green, C.; Kennard, H.; Lampard, P.; Scamman, D.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Ford, L.B.; et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 2022, 400, 1619–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, P.L.; Douglas, K.A.; Hu, W. Primary care in disasters: Opportunity to address a hidden burden of health care. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 210, 297–299.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, R.; McGirr, J. Preparing rural general practitioners and health services for climate change and extreme weather. Aust. J. Rural Health 2014, 22, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yu, P.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Beggs, P.J.; Zhang, Y.; Boocock, J.; et al. Climate change, environmental extremes, and human health in Australia: Challenges, adaptation strategies, and policy gaps. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2023, 40, 100936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.; Gray, M.; Hunter, B. The Impact of Drought on Mental Health in Rural and Regional Australia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, G.; Hanna, L.; Kelly, B. Drought, drying and climate change: Emerging health issues for ageing Australians in rural areas. Australas. J. Ageing 2010, 29, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanigan, I.C.; Schirmer, J.; Niyonsenga, T. Drought and Distress in Southeastern Australia. EcoHealth 2018, 15, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrien, L.V.; Berry, H.L.; Coleman, C.; Hanigan, I.C. Drought as a mental health exposure. Environ. Res. 2014, 131, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.K.; Handley, T.; Kiem, A.S.; Rich, J.L.; Lewin, T.J.; Askland, H.H.; Askarimarnani, S.S.; Perkins, D.A.; Kelly, B.J. Drought-related stress among farmers: Findings from the Australian Rural Mental Health Study. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.; Bain-Donohue, S.; Dewi, S.P. The impact of extreme heat on older regional and rural Australians: A systematic review. Aust. J. Rural Health 2024, 32, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E.; Honan, B.; Quilty, S.; Schultz, R. The Effect of Heat Events on Prehospital and Retrieval Service Utilization in Rural and Remote Areas: A Scoping Review. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegasothy, E.; McGuire, R.; Nairn, J.; Fawcett, R.; Scalley, B. Extreme climatic conditions and health service utilisation across rural and metropolitan New South Wales. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 61, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longman, J.M.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Matthews, V.; Berry, H.L.; Passey, M.E.; Rolfe, M.; Morgan, G.G.; Braddon, M.; Bailie, R. Rationale and methods for a cross-sectional study of mental health and wellbeing following river flooding in rural Australia, using a community-academic partnership approach. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, V.; Longman, J.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Braddon, M.; Passey, M.; Bailie, R.S.; Berry, H.L. Belonging and Inclusivity Make a Resilient Future for All: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Post-Flood Social Capital in a Diverse Australian Rural Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, L.; Waters, E.; Bryant, R.A.; Pattison, P.; Lusher, D.; Harms, L.; Richardson, J.; MacDougall, C.; Block, K.; Snowdon, E.; et al. Beyond Bushfires: Community, Resilience and Recovery—A longitudinal mixed method study of the medium to long term impacts of bushfires on mental health and social connectedness. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A.; Gallagher, H.C.; Gibbs, L.; Pattison, P.; MacDougall, C.; Harms, L.; Block, K.; Baker, E.; Sinnott, V.; Ireton, G.; et al. Mental Health and Social Networks After Disaster. Am. J. Psychiat. 2016, 174, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, R.J.; Jones, R.; Reupert, A. In the wake of the 2009 Gippsland fires: Young adults’ perceptions of post-disaster social supports. Aust. J. Rural Health 2012, 20, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Workman, A.; Russell, M.A.; Williamson, M.; Pan, H.; Reifels, L. The long-term impact of bushfires on the mental health of Australians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2022, 13, 2087980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyafei, A.; Easton-Carr, R. The Health Belief Model of Behavior Change. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606120/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbrink, T.; Willcock, S. Place attachment and perception of climate change as a threat in rural and urban areas. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buikstra, E.; Ross, H.; King, C.A.; Baker, P.G.; Hegney, D.; McLachlan, K.; Rogers-Clark, C. The components of resilience—Perceptions of an Australian rural community. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 38, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, W.; O’Mullan, C. Perceptions of community resilience after natural disaster in a rural Australian town. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 44, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Semenza, J.C. Community-Based Adaptation to the Health Impacts of Climate Change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, R.; Klein, W.M. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Lykins, A.D. Cultural worldviews and the perception of natural hazard risk in Australia. Environ. Hazards 2023, 22, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaker, J.; Richardson, L.M.; Holmes, D.C. Australians’ perceptions about health risks associated with climate change: Exploring the role of media in a comprehensive climate change risk perception model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 89, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, R.; McGirr, J. Rural health service managers’ perspectives on preparing rural health services for climate change. Aust. J. Rural Health 2018, 26, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, J.; Maibach, E.W. Health Implications of Climate Change: A Review of the Literature About the Perception of the Public and Health Professionals. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykins, A.D.; Parsons, M.; Craig, B.M.; Cosh, S.M.; Hine, D.W.; Murray, C. Australian Youth Mental Health and Climate Change Concern After the Black Summer Bushfires. EcoHealth 2023, 20, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.P.; Jamieson, J.; Gibson, K.; Duffy, M.; Williamson, M.; Parr, H. Eco-anxiety among regional Australian youth with mental health problems: A qualitative study. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2024, 18, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Remoteness Areas—Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Edition 3. Canberra 2023. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3/jul2021-jun2026/remoteness-structure/remoteness-areas (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Nelson, K.S.; Nguyen, T.D.; Brownstein, N.A.; Garcia, D.; Walker, H.C.; Watson, J.T.; Xin, A. Definitions, measures, and uses of rurality: A systematic review of the empirical and quantitative literature. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Perception and Understanding of Self. 2025. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-funded-by-nimh/rdoc/constructs/perception-and-understanding-of-self (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote. In EndNote, 20th ed.; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2024; Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. Enduring drought then coping with climate change: Lived experience and local resolve in rural mental health. Rural Soc. 2009, 19, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnie, T.L.; Berry, H.L.; Blinkhorn, S.A.; Hart, C.R. In their own words: Young people’s mental health in drought-affected rural and remote NSW. Aust. J. Rural Health 2011, 19, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, J.; King, D.; Lane, A.; MacDougall, C. Understanding resilience in South Australian farm families. Rural Soc. 2009, 19, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healing, K.; Lowrie, D. Exploring the occupational experiences of livestock farmers during drought: A narrative inquiry. Aust. J. Rural Health 2023, 31, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, R.H.; Mitchell, E.; Whitehead-Annett, L.; Duncan, Z.; McArdle, A. Natural disasters and perinatal mental health: What are the impacts on perinatal women and the service system? J. Public Health 2024, 32, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, A.; Olcoń, K.; Smith, L.; Allan, J.; Pai, P. Wellness Warriors: A qualitative exploration of healthcare staff learning to support their colleagues in the aftermath of the Australian bushfires. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2167298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, W.; Judd, J.; Williams, S.L.; McKenzie, F.; Deagon, J.; Ames, K. Time as a Social and Environmental Determinant of Health for Rural Women. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, C.E.; Lykins, A.D.; Bartik, W.; Tully, P.J.; Cosh, S.M. Climate Change in Rural Australia: Natural Hazard Preparedness and Recovery Needs of a Rural Community. Climate 2024, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, C.W.; Rosen, A.; Berry, H.L.; Hart, C.R. If the land’s sick, we’re sick: The impact of prolonged drought on the social and emotional well-being of Aboriginal communities in rural New South Wales. Aust. J. Rural Health 2011, 19, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartore, G.M.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Albrecht, G.; Higginbotham, N. Control, uncertainty, and expectations for the future: A qualitative study of the impact of drought on a rural Australian community. Rural Remote Health 2008, 8, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniford, A.K.; Dollard, M.F.; Guerin, B. Stress and help-seeking for drought-stricken citrus growers in the Riverland of South Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2009, 17, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stribley, L.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Dallinger, V.; Ma, J.; Nielsen, T.; Bryce, I.; Rees, B.; Morse, A.; Rogers, M.; Burton, L. Post-Disaster Social Connectedness in Parent–Child Dyads: A Qualitative Investigation of Changes in Coping and Social Capital of Rural Australian Families Following Bushfires. Br. J. Soc. Work 2024, 55, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Martin, E.; Isobel, S. ‘Profound personal and professional impacts’: A qualitative study of clinician experiences of a mental health disaster response to Australia’s black summer bushfires. Aust. J. Rural Health 2024, 32, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kruk, S.R.; Gunn, K.M. ‘It sort of broke me’: A thematic analysis of the psychological experiences and coping strategies employed by Australian fire-affected farmers. Aust. J. Rural Health 2024, 32, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J.; Handmer, J.; Mercer, D. Vulnerability to bushfires in rural Australia: A case study from East Gippsland, Victoria. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Bi, P.; Newbury, J.; Robinson, G.; Pisaniello, D.; Saniotis, A.; Hansen, A. Extreme heat and health: Perspectives from health service providers in rural and remote communities in South Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 5565–5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Hanson-Easey, S.; Robinson, G.; Pisaniello, D.; Newbury, J.; Saniotis, A.; Bi, P. Heat adaptation and place: Experiences in South Australian rural communities. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.K.; Rich, J.L.; Kiem, A.S.; Handley, T.; Perkins, D.; Kelly, B.J. Concerns about climate change among rural residents in Australia. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 75, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailie, J.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R.; Villeneuve, M.; Longman, J. Exposure to risk and experiences of river flooding for people with disability and carers in rural Australia: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.; Xue, H.; Carlson, J.; Gray, J.M.; Bailey, J.; Vines, R. Impact of COVID-19 on lifestyle and mental wellbeing in a drought-affected rural Australian population. Rural Remote Health 2022, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennell, K.M.; Jarrett, C.E.; Kettler, L.J.; Dollman, J.; Turnbull, D.A. “Watching the bank balance build up then blow away and the rain clouds do the same”: A thematic analysis of South Australian farmers’ sources of stress during drought. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 46, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.C.; King, J.C.; Aitken, P.J.; Leggat, P.A. “Washed away”-assessing community perceptions of flooding and prevention strategies: A North Queensland example. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 1977–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, K.M.; Kettler, L.J.; Skaczkowski, G.L.A.; Turnbull, D.A. Farmers’ stress and coping in a time of drought. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Luk, M.; Longman, J. Young people’s experiences of the Northern Rivers 2017 flood and its effects on their mental health. Aust. J. Rural Health 2024, 32, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, B.; Taylor, M.; Stevens, G.; Barr, M.; Gorringe, M.; Agho, K. Factors associated with population risk perceptions of continuing drought in Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2009, 17, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Hanson-Easey, S.; Nitschke, M.; Howell, S.; Nairn, J.; Beattie, C.; Wynwood, G.; Bi, P. Heat-health warnings in regional Australia: Examining public perceptions and responses. Environ. Hazards 2019, 18, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailie, J.; Reed, K.; Matthews, V.; Scott, K.M.; Ahern, C.; Bailie, R. Volunteering as prosocial behaviour by medical students following a flooding disaster and impacts on their mental health: A mixed-methods study. Med. Educ. 2023, 58, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, R.; Robinson, P.; Smith, P. From hypothetical scenario to tragic reality: A salutary lesson in risk communication and the Victorian 2009 bushfires. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2010, 34, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, J.; Stain, H.J. The impact of drought on the emotional well-being of children and adolescents in rural and remote New South Wales. J. Rural Health 2007, 23, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.G.; Stain, H.J. Mental health impact for adolescents living with prolonged drought. Aust. J. Rural Health 2010, 18, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, M.E.; Carroll, M.; Tapper, N. Learning from our older people: Pilot study findings on responding to heat. Australas. J. Ageing 2014, 33, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, K.; Turner, L.R.; Tong, S. Floods and human health: A systematic review. Environ. Int. 2012, 47, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Black, J.; Jones, M.; Wilson, L.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Astell-Burt, T.; Black, D.; Ebi, K.L. Flooding and Mental Health: A Systematic Mapping Review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanke, C.; Kerac, M.; Prudhomme, C.; Medlock, J.; Murray, V. Health effects of drought: A systematic review of the evidence. PLoS Curr. 2013, 5, ecurrents.dis.7a2cee9e980f91ad7697b570bcc4b004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.; White, P.C.L.; Bell, A.; Coventry, P.A. Effect of Extreme Weather Events on Mental Health: A Narrative Synthesis and Meta-Analysis for the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. Beliefs and Denials About Climate Change: An Australian Perspective. Ecopsychology 2012, 4, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensor, J.; Harvey, B. Social learning and climate change adaptation: Evidence for international development practice. WIREs Clim. Change 2015, 6, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiem, A.S.; Austin, E.K. Drought and the future of rural communities: Opportunities and challenges for climate change adaptation in regional Victoria, Australia. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T.; Jones-Casey, K.; Tasala, K. Mapping the solastalgia literature: A scoping review study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-García, V.; García-Del-Amo, D.; Porcuna-Ferrer, A.; Schlingmann, A.; Abazeri, M.; Attoh, E.M.N.A.N.; Ávila, J.V.d.C.; Ayanlade, A.; Babai, D.; Benyei, P.; et al. Local studies provide a global perspective of the impacts of climate change on Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longman, J.; Braddon, M.; Verlie, B.; Schlosberg, D.; Hampshire, L.; Hawke, C.; Noonan, A.; Saurman, E. Building resilience to the mental health impacts of climate change in rural Australia. J. Clim. Change Health 2023, 12, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattidge, L.; Hoang, H.; Mond, J.; Visentin, D.; Lees, D.; Auckland, S. The Community’s Role in Rural Youth Suicide Prevention: Perspectives from the Field. Aust. J. Rural Health 2025, 33, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattidge, L.; Purton, T.; Auckland, S.; Lees, D.; Mond, J. Participatory action research in suicide prevention program evaluation: Opportunities and challenges from the National Suicide Prevention Trial, Tasmania. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2021, 45, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, K.M.; Barrett, A.; Hughes-Barton, D.; Turnbull, D.; Short, C.E.; Brumby, S.; Skaczkowski, G.; Dollman, J. What farmers want from mental health and wellbeing-focused websites and online interventions. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, T.E.; Kay-Lambkin, F.J.; Inder, K.J.; Lewin, T.J.; Attia, J.R.; Fuller, J.; Perkins, D.; Coleman, C.; Weaver, N.; Kelly, B.J. Self-reported contacts for mental health problems by rural residents: Predicted service needs, facilitators and barriers. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, S.A.; Reser, J.P. Natural disasters, climate change and mental health considerations for rural Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2007, 15, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, P.; Tyler, M.; Hart, A.; Mees, B.; Phillips, R.; Stratford, J.; Toh, K. Creating “Community”? Preparing for Bushfire in Rural Victoria. Rural Sociol. 2013, 78, 186–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokmic-Tomkins, Z.; Bhandari, D.; Watterson, J.; Pollock, W.E.; Cochrane, L.; Robinson, E.; Su, T.T. Multilevel interventions as climate change adaptation response to protect maternal and child health: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e073960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rural | Extreme Weather Event | Health Impact | Perceptions | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural population (MeSH) Rural Regional Remote Provincial Peri-rural Peri-urban | Extreme weather (MeSH) Natural disasters (MeSH) Extreme event Adverse climate event Extreme / severe heat / temperature Extreme / severe storm Heatwave Bushfire Extreme rain / rainfall / precipitation Flood, flooding Drought | Health | Health knowledge Health attitudes Health perceptions Risk perception Patient perceptions Community perceptions Public attitudes Perceptions Perspectives Concerns Beliefs Attitudes Awareness | Australia New South Wales, NSW Victoria, Vic Queensland, Qld South Australia, SA Tasmania, Tas Northern Territory, NT Australian Capital Territory, ACT Western Australia, WA |

| Study Characteristic | Publication (n = 34) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | ||

| Qualitative | 19 | [30,36,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] |

| Semi-structured interviews | 12 | [30,53,55,56,57,58,60,63,64,65,66,68] |

| Interviews and focus groups | 3 | [36,62,69] |

| Forums | 3 | [54,59,61] |

| Interviews and informal discussions | 1 | [67] |

| Quantitative | 10 | [27,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] |

| Cross-sectional survey | 10 | [27,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] |

| Mixed methods | 5 | [79,80,81,82,83] |

| Survey and focus groups | 4 | [79,80,81,82] |

| Focus groups, interviews and meteorological data survey | 1 | [83] |

| Location | ||

| New South Wales (NSW) | 15 | [27,54,58,60,61,62,65,70,71,72,76,77,79,81,82] |

| South Australia (SA) | 7 | [55,63,64,68,69,73,75] |

| Victoria (Vic) | 6 | [30,53,57,67,80,83] |

| Queensland (Qld) | 4 | [36,56,59,74] |

| SA and Vic | 1 | [78] |

| SA and NSW | 1 | [66] |

| Extreme weather event | ||

| Drought | 14 | [53,54,55,56,59,61,62,63,72,73,75,77,81,82] |

| Bushfire | 8 | [30,58,60,64,65,66,67,80] |

| Flood | 6 | [27,36,71,74,76,79] |

| Extreme heat | 4 | [68,69,78,83] |

| Flood, bushfire and drought | 1 | [57] |

| Flood and drought | 1 | [70] |

| Age | ||

| Children and adolescents | 4 | [54,64,81,82] |

| Young adults | 3 | [30,76,79] |

| Adults | 26 | [27,36,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,77,78,80] |

| Older adults | 1 | [83] |

| Occupation | ||

| Farmers | 6 | [55,56,63,66,73,75] |

| Health workers or service providers | 5 | [53,57,58,65,68] |

| Both farmers and other | 5 | [36,59,62,67,69] |

| School students | 4 | [54,64,81,82] |

| Medical students | 1 | [79] |

| Other | 3 | [61,72,80] |

| Not specified | 10 | [27,30,60,70,71,74,76,77,78,83] |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 4 | [36,53,57,59] |

| Male | 0 | |

| Mixed | 30 | [27,30,54,55,56,58,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vohralik, E.; Mond, J.; Sutarsa, I.N.; Hall Dykgraaf, S.; Humber, B.; Dewi, S. The Perceptions of Rural Australians Concerning the Health Impacts of Extreme Weather Events: A Scoping Review. Climate 2025, 13, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13090180

Vohralik E, Mond J, Sutarsa IN, Hall Dykgraaf S, Humber B, Dewi S. The Perceptions of Rural Australians Concerning the Health Impacts of Extreme Weather Events: A Scoping Review. Climate. 2025; 13(9):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13090180

Chicago/Turabian StyleVohralik, Emily, Jonathan Mond, I. Nyoman Sutarsa, Sally Hall Dykgraaf, Breanna Humber, and Sari Dewi. 2025. "The Perceptions of Rural Australians Concerning the Health Impacts of Extreme Weather Events: A Scoping Review" Climate 13, no. 9: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13090180

APA StyleVohralik, E., Mond, J., Sutarsa, I. N., Hall Dykgraaf, S., Humber, B., & Dewi, S. (2025). The Perceptions of Rural Australians Concerning the Health Impacts of Extreme Weather Events: A Scoping Review. Climate, 13(9), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13090180