The Interplay Between Climate Change Exposure, Awareness, Coping, and Anxiety Among Individuals with and Without a Chronic Illness

Abstract

1. Introduction

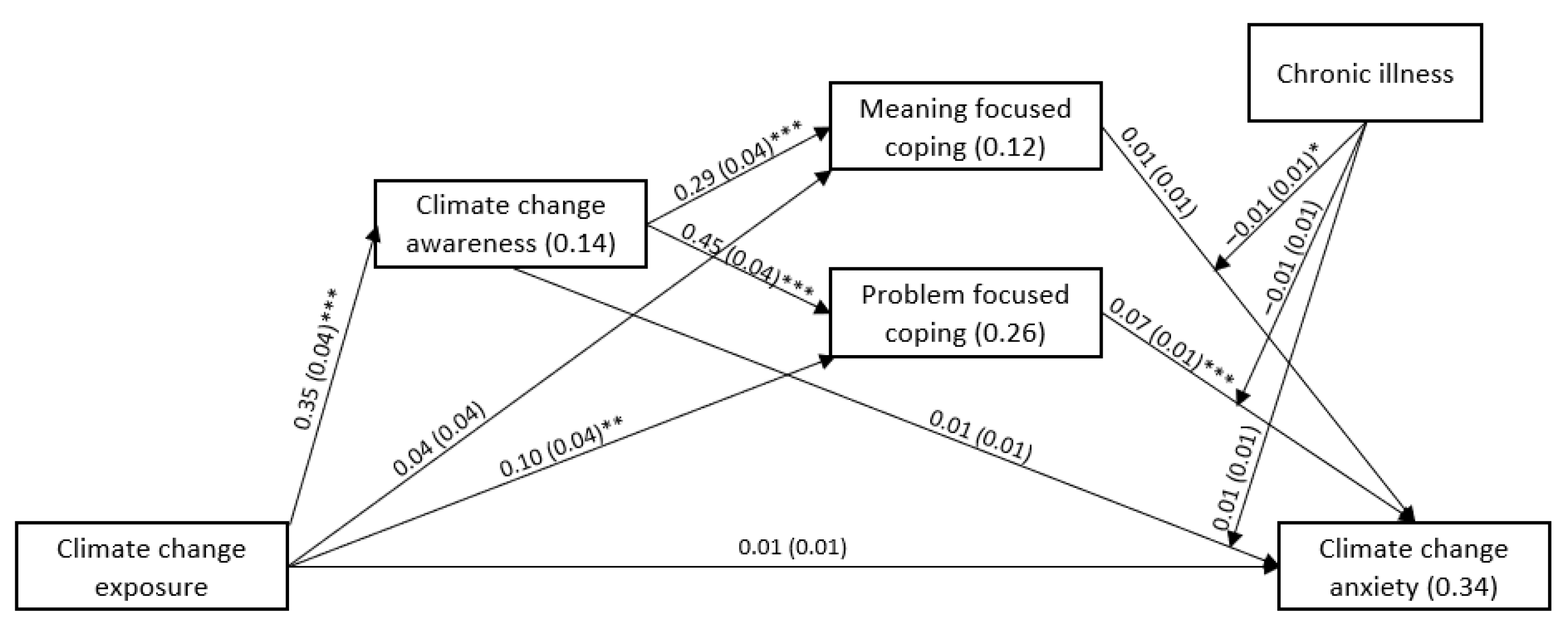

- Higher climate change exposure would be associated with higher climate change awareness, which, in turn, would be associated with higher CCA.

- Higher climate change exposure would be associated with a greater use of meaning-focused and problem-focused coping, which, in turn, would be associated with higher CCA. However, higher climate change exposure would be associated with a lower use of de-emphasizing the seriousness of climate change, which, in turn, would be associated with higher CCA.

- Higher climate change exposure would be associated with higher climate change awareness, which, in turn, would be associated with a greater use of meaning-focused and problem-focused coping and a lower use of de-emphasizing the seriousness of climate change, all of which would subsequently be associated with higher CCA.

- Having a chronic illness would moderate the associations between climate change awareness and coping strategies on the one hand and CCA on the other hand, such that these associations would be stronger for people with a chronic illness than for people without one.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.1.1. Associations with the Demographic Variables

4.1.2. The Study Model

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Implications

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz, S.; Díaz, J.; Negev, M.; Linares, C. Climate change and global health. In Handbook of Epidemiology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderbauer, S.; Pisa, P.F.; Delves, J.L.; Pedoth, L.; Rufat, S.; Erschbamer, M.; Thaler, T.; Carnelli, F.; Granados-Chahin, S. Risk perception of climate change and natural hazards in global mountain regions: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 146957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gönen, Ç.; Deveci, E.Ü.; Aydede, M.N. Development and validation of climate change awareness scale for high school students. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 4525–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, D.A.; Begotti, T. Media exposure to climate change, anxiety, and efficacy beliefs in a sample of Italian university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama-Raz, Y.; Shinan-Altman, S. Does climate change worry decrease during armed conflicts? Climate 2024, 12, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The Extended Parallel Process Model. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N.; Real, K. Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change: Use of the Risk Perception Attitude (RPA) framework to understand health behaviors. Hum. Commun. Res. 2003, 29, 370–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L. The climate anxiety compass: A framework to map the solution space for coping with climate anxiety. Dialogues Clim. Change 2024, 1, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.V.; Li, X.; Curran, M.A.; Barnett, M.A. Coping profiles in the context of global environmental threats: A person-centered approach. Anxiety Stress Coping 2022, 35, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.W.; Tam, K.P.; Clayton, S. Testing an integrated model of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocque, R.J.; Beaudoin, C.; Ndjaboue, R.; Cameron, L.; Poirier-Bergeron, L.; Poulin-Rheault, R.A.; Fallon, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Witteman, H.O. Health effects of climate change: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinan-Altman, S.; Hamama-Raz, Y. Factors associated with pro-environmental behaviors in Israel: A comparison between participants with and without a chronic disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.; Hsu, S.; Ragunathan, S.; Lindsay, J. The impact of climate change-related extreme weather events on people with pre-existing disabilities and chronic conditions: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 4338–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: A narrative review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Psychology of climate change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 391–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L.; De Jonge, P. Climate anxiety: A research agenda inspired by emotion research. Emotion Rev. 2023, 15, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodas, M.; Siman-Tov, M.; Kreitler, S.; Peleg, K. Psychological correlates of civilian preparedness for conflicts. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2017, 11, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Abstract of Israel 2023—No. 74; CBS: Jerusalem, Israel, 2023. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/DocLib/isr_in_n/isr_in_n23e.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Kenny, D.A. MedPower: An Interactive Tool for the Estimation of Power in Tests of Mediation [Computer Software]. 2017. Available online: https://davidakenny.shinyapps.io/MedPower/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. Israel’s Religiously Divided Society [Internet]. 8 March 2016. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2016/03/08/israels-religiously-divided-society/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Benyamini, Y.; Blumstein, T.; Lusky, A.; Modan, B. Gender differences in the self-rated health–mortality association: Is it poor self-rated health that predicts mortality or excellent self-rated health that predicts survival? Gerontologist 2003, 43, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Gjersoe, N.; O’Neill, S.; Barnett, J. Youth perceptions of climate change: A narrative synthesis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2020, 11, e641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediz, Ç.; Yanik, D. The effects of climate change awareness on mental health: Comparison of climate anxiety and hopelessness levels in Turkish youth. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2023, 69, 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U. Experience-based and description-based perceptions of long-term risk: Why global warming does not scare us (yet). Clim. Change 2006, 77, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. Perceived temporal and geographic distance and public opinion about climate change. Oxford Res. Encycl. Clim. Sci. 2016. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/climatescience/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228620-e-308 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Ballew, M.T.; Uppalapati, S.S.; Myers, T.; Carman, J.; Campbell, E.; Rosenthal, S.A.; Kotcher, J.E.; Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E. Climate change psychological distress is associated with increased collective climate action in the U.S. npj Clim. Action 2024, 3, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daeninck, C.; Kioupi, V.; Vercammen, A. Climate anxiety, coping strategies and planning for the future in environmental degree students in the UK. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1126031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Su, Y. Low-carbon awareness and behaviors: Effects of exposure to climate change impact photographs. SAGE Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricart, S.; Gandolfi, C.; Castelletti, A. Climate change awareness, perceived impacts, and adaptation from farmers’ experience and behavior: A triple-loop review. Reg. Environ. Change 2023, 23, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikner Martinsson, A.; Ojala, M. Patterns of climate-change coping among late adolescents: Differences in emotions concerning the future, moral responsibility, and climate-change engagement. Clim. Change 2024, 177, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress Coping 2008, 21, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Regulating worry, promoting hope: How do children, adolescents, and young adults cope with climate change? Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2012, 7, 537–561. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation theory and preventive health: Beyond the health belief model. Health Educ. Res. 1986, 1, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, E.J.; Ling, M.; North, M.; Klas, A.; Mullan, B.A.; Novoradovskaya, L. Protection motivation theory and pro-environmental behaviour: A systematic mapping review. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, E.; Frumento, S.; Gemignani, A.; Menicucci, D. Personality traits and climate change denial, concern, and proactivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | Male | 300 (50.0) |

| Female | 300 (50.0) | |

| Age, M (SD), range | 49.83 (16.71), 20–80 | |

| Marital status, n (%) | Single | 96 (16.0) |

| Married, in a relationship | 438 (73.0) | |

| Divorced, widowed, other | 66 (11.0) | |

| Children, n (%) | Yes | |

| Number of children, M (SD), range | 2.20 (1.72), 0–11 | |

| Years of education, M (SD), range | 14.85 (2.80), 8–26 | |

| Employment, n (%) | Yes | 450 (75.0) |

| Income, compared to the general Israeli population n (%) (n = 586) | Below average | 204 (34.8) |

| Average | 159 (27.1) | |

| Above average | 233 (38.1) | |

| Religiosity, n (%) | Secular | 311 (51.8) |

| Traditional | 187 (31.2) | |

| Religious | 102 (17.0) | |

| Health status, n (%) | Bad or not so good | 73 (12.2) |

| Good | 402 (67.0) | |

| Excellent | 125 (20.8) | |

| Chronic illness, n (%) | Yes | 323 (53.8) |

| Variables | M (SD) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Chronic illness (yes) | 0.54 (0.50) | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Climate change exposure | 1.95 (1.60) | 0.07 | 1 | |||||

| 3. Climate change awareness | 3.48 (0.70) | 0.05 | 0.33 *** | 1 | ||||

| 4. Meaning-focused coping | 2.87 (0.56) | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.28 *** | 1 | |||

| 5. Problem-focused coping | 2.39 (0.81) | 0.04 | 0.24 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.39 *** | 1 | ||

| 6. De-emphasizing seriousness | 2.31 (0.64) | −0.01 | −0.31 *** | −0.56 *** | 0.02 | −0.35 *** | 1 | |

| 7. Climate change anxiety | 1.32 (0.49) | 0.13 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.25 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.54 *** | −0.12 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shinan-Altman, S.; Hamama-Raz, Y. The Interplay Between Climate Change Exposure, Awareness, Coping, and Anxiety Among Individuals with and Without a Chronic Illness. Climate 2025, 13, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13060124

Shinan-Altman S, Hamama-Raz Y. The Interplay Between Climate Change Exposure, Awareness, Coping, and Anxiety Among Individuals with and Without a Chronic Illness. Climate. 2025; 13(6):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13060124

Chicago/Turabian StyleShinan-Altman, Shiri, and Yaira Hamama-Raz. 2025. "The Interplay Between Climate Change Exposure, Awareness, Coping, and Anxiety Among Individuals with and Without a Chronic Illness" Climate 13, no. 6: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13060124

APA StyleShinan-Altman, S., & Hamama-Raz, Y. (2025). The Interplay Between Climate Change Exposure, Awareness, Coping, and Anxiety Among Individuals with and Without a Chronic Illness. Climate, 13(6), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13060124