Support Needs of Agrarian Women to Build Household Livelihood Resilience: A Case Study of the Mekong River Delta, Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To examine how rural women in the MRD perceive the impact of CC on their household livelihood resilience (HLR);

- To identify the specific support needs that women prioritize in enhancing their HLR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

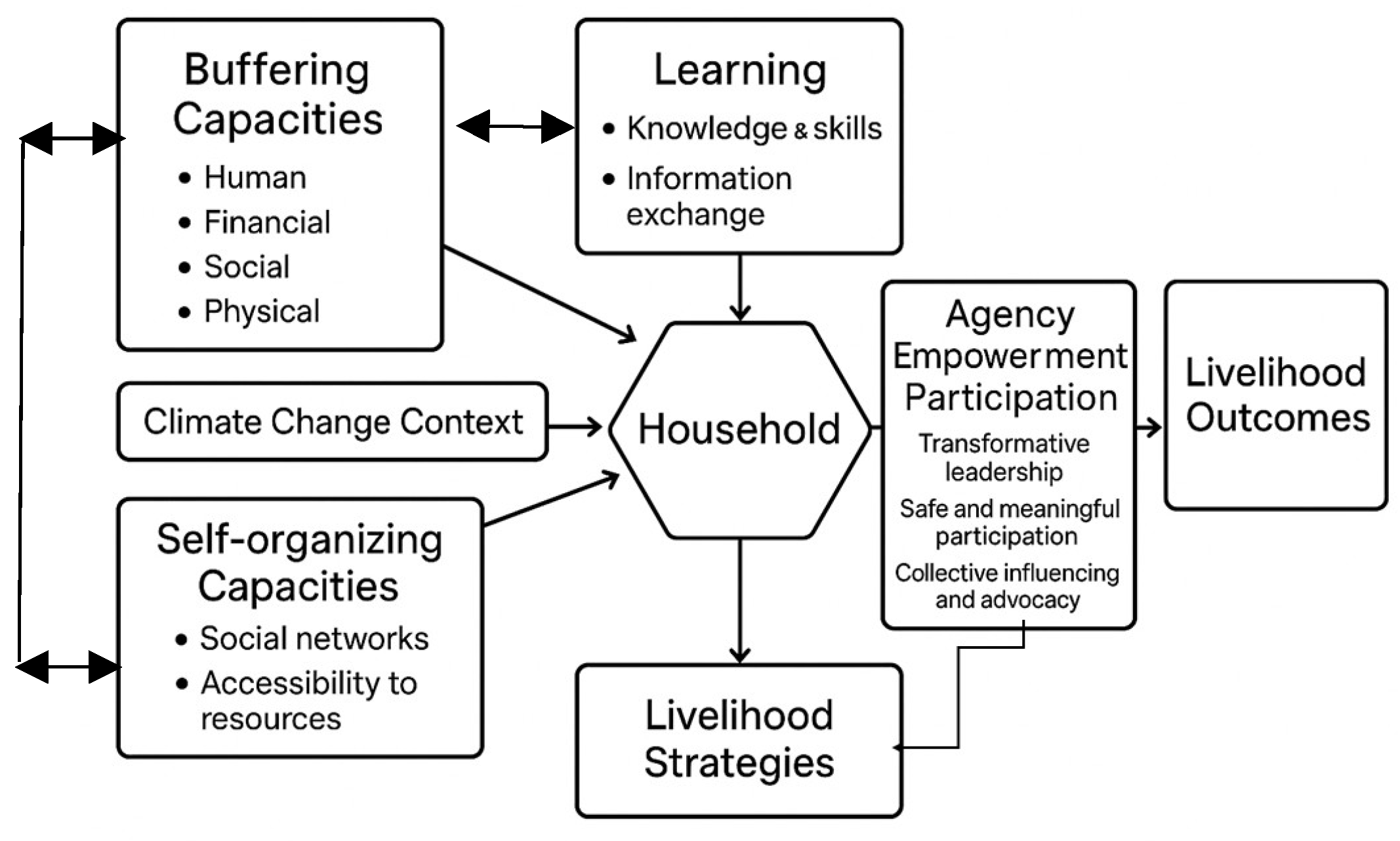

2.2. Conceptual Framework

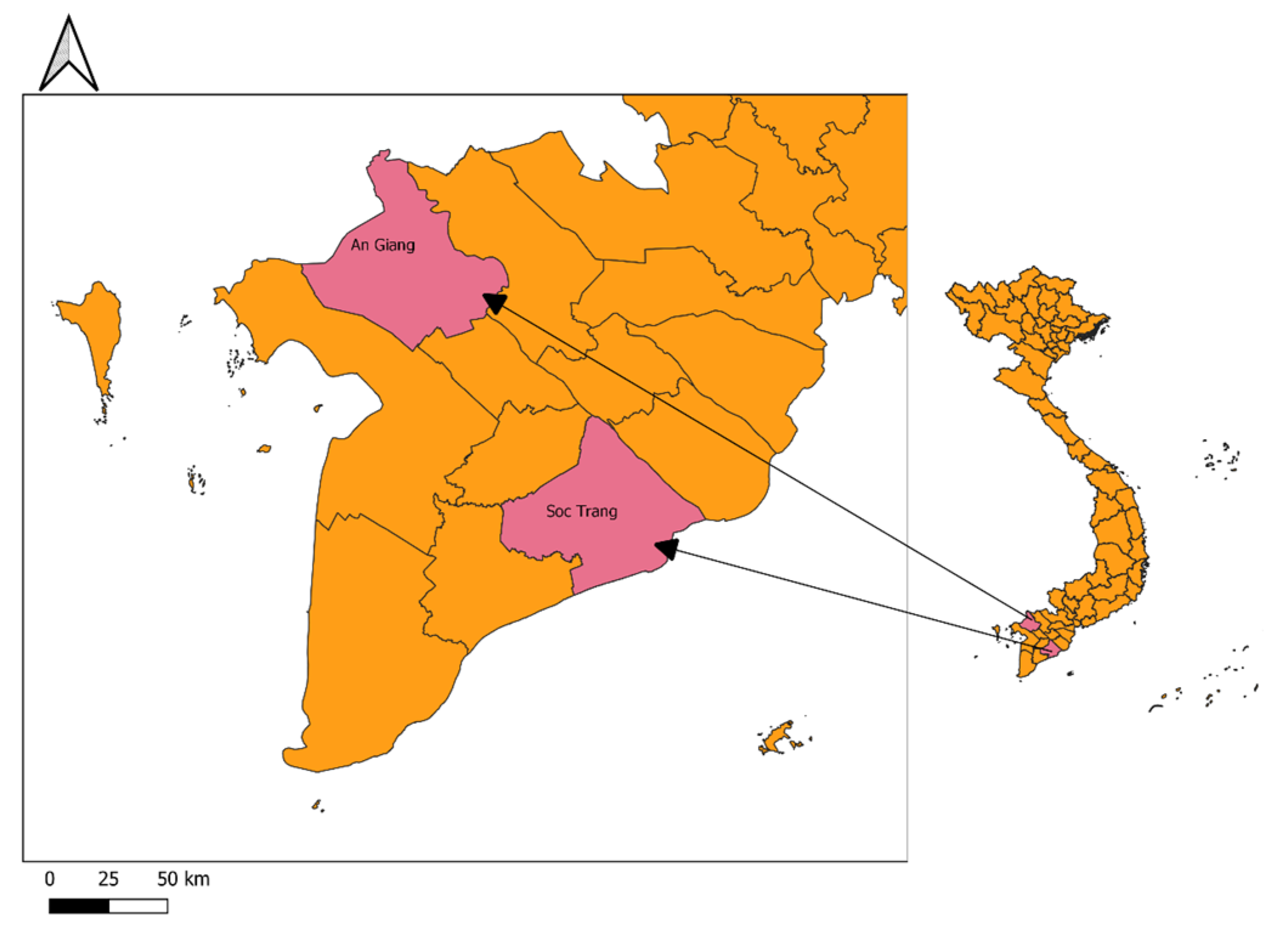

2.3. Case Study Sites

2.4. Research Participants

2.5. Data Collection Procedures

2.6. Data Validation

2.7. Data Analysis

2.7.1. Qualitative Analysis

2.7.2. Historical Event Analysis

2.7.3. Soft Systems Methodology with CATWOE Analysis

2.7.4. Quantitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Community Representation

3.2. Women’s Perception of HLR to CC

3.2.1. Awareness, Vulnerability, and Gaps in CC Understanding

3.2.2. Adaptive Responses

3.3. Factors Influencing HLR

3.3.1. The Role of Financial Capital in Enabling or Constraining HLR

3.3.2. Social Capitals and Informal Networks as Pillars of HLR

3.3.3. Gendered Responsibilities and Decision-Making

3.4. Perceived Support Needs for Agrarian Women’s HLR

3.4.1. Monetary, Technical, and Leadership Support Needs

3.4.2. Stakeholder Roles and Support Ecosystem

4. Discussion

4.1. Household Livelihood Resilience Among Agrarian Women in Rural Climate Contexts

4.2. Two Sides of HLR: Strengths and Shortfalls in Rural Women’s Livelihood Adaptation

4.3. Rural Women’s Perceived Needs as a Blueprint for Building Livelihood Resilience

4.4. The Missing Links in HLR Interventions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, M.; Dube, O.P.; Solecki, W.; Aragón-Durand, F.; Cramer, W.; Humphreys, S.; Kainuma, M. Special report: Global warming of 1.5 °C. Intergov. Panel Clim. Change 2018, 27, 677. [Google Scholar]

- Bolan, S.; Padhye, L.P.; Jasemizad, T.; Govarthanan, M.; Karmegam, N.; Wijesekara, H.; Amarasiri, D.; Hou, D.; Zhou, P.; Biswal, B.K.; et al. Impacts of climate change on the fate of contaminants through extreme weather events. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, W.; Marcheggiani, S.; Puccinelli, C.; Carere, M.; Sofia, T.; Giuliano, F.; Dogliotti, E.; Mancini, L.; Agrimi, U.; Alleva, E.; et al. Health and Climate Change: Science calls for global action. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2019, 55, 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, J.; Oliveira, S.; Viana, C.M.; Ribeiro, A.I. Chapter 8—Climate change and its impacts on health, environment and economy. In One Health; Prata, J.C., Ribeiro, A.I., Rocha-Santos, T., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Elsevier: London, UK, 2022; pp. 253–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kuran, C.H.A.; Morsut, C.; Kruke, B.I.; Krüger, M.; Segnestam, L.; Orru, K.; Naevestad, T.O.; Airola, M.; Keranen, J.; Gabel, F.; et al. Vulnerability and vulnerable groups from an intersectionality perspective. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazebrook, T.; Noll, S.; Opoku, E. Gender matters: Climate change, gender bias, and women’s farming in the global South and North. Agriculture 2020, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Clause, V.; Mattern, M.; Zani, K. Strengthening Rural Women’s Climate Resilience: Opportunities for Financial and Agricultural Service Providers; CGAP Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/Working%20Paper-RRW_CGAP-Agrifin.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Contzen, S.; Forney, J. Family farming and gendered division of labour on the move: A typology of farming-family configurations. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberger, T.; Mueller, M.; Spangler, T.; Alexander, S. Community Resilience: Conceptual Framework and Measurement Feed the Future Learning Agenda; Westat: Rockville, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Asmamaw, M.; Mereta, S.T.; Ambelu, A. Exploring households’ resilience to climate change-induced shocks using Climate Resilience Index in Dinki watershed, central highlands of Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, N.; Lawson, E.T.; Raditloaneng, W.N.; Solomon, D.; Angula, M.N. Gendered vulnerabilities to climate change: Insights from the semi-arid regions of Africa and Asia. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyer, S.; Gumucio, T. Going back to the well: Women, agency, and climate adaptation. World J. Agric. Soil Sci. 2020, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Addressing gender inequalities to build resilience. In Stocktaking of Good Practices in the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ Strategic Objective 5; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal-Escobar, Y.; Quintero-Angel, M.; Garcia-Vargas, M. Women’s role in adapting to climate change and variability. Adv. Geosci. 2008, 14, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namiech, O. Women’s livelihoods and resilience in complex and volatile environments. In An Analysis of Best Practices; JDC: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, I. Gender in climate change and disaster risk reduction, Manila, October 2008. Dev. Pract. 2009, 6, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djoudi, H.; Brockhaus, M. Is adaptation to climate change gender neutral? Lessons from communities dependent on livestock and forests in northern Mali. Int. For. Rev. 2011, 13, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, C.I.; Wiesmann, U.; Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social–ecological dynamics. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A. Measuring livelihood resilience: The household livelihood resilience approach (HLRA). World Dev. 2018, 107, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for International Development. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; DFID: London, UK, 1999. Available online: https://www.livelihoodscentre.org/documents/114097690/114438878/Sustainable+livelihoods+guidance+sheets.pdf/594e5ea6-99a9-2a4e-f288-cbb4ae4bea8b?t=1569512091877 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Greene, C.; Wilmer, H.; Ferguson, D.B.; Crimmins, M.A.; McClaran, M.P. Using scale and human agency to frame ranchers’ discussions about socio-ecological change and resilience. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 96, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngigi, M.W.; Mueller, U.; Birner, R. Gender differences in climate change adaptation strategies and participation in group-based approaches: An intra-household analysis from rural Kenya. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 138, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, E.; Alvi, M.; Huyer, S.; Ringler, C. Addressing gender inequalities and strengthening women’s agency to create more climate-resilient and sustainable food systems. Glob. Food Secur. 2024, 40, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASEAN. ASEAN Master Plan on Rural Development 2022 to 2026; ASEAN: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022; Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/34-ASEAN-Master-Plan-on-Rural-Development-2022-2026.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Sentian, J.; Payus, C.M.; Herman, F.; Kong, V.W.Y. Climate change scenarios over Southeast Asia. APN Sci. Bull. 2022, 12, 102–122. Available online: https://www.apn-gcr.org/bulletin/article/climate-change-scenarios-over-southeast-asia/ (accessed on 28 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.-C.; Pross, C.A.; Agarwal, R.A.; Raluca Torre, A. The State of Gender Equality and Climate Change in ASEAN; ASEAN: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022; Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/State-of-Gender-Equality-and-Climate-Change-in-ASEAN_FINAL-1.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Zhou, W.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Livelihood resilience and strategies of rural residents of earthquake-threatened areas in Sichuan Province, China. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, K.; Shepherd, A. Chronic Poverty in Semi Arid Zimbabwe; CPRC Working Paper No 18; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2003; p. 59. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08d1240f0b652dd00173c/18Bird_Shepherd.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Feldman, M. Livelihood adaptive capacities and adaptation strategies of relocated households in rural China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1067649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, G.D.; Aggarwal, P.K.; Poudel, S.; Belgrave, D.A. Climate-induced migration in South Asia: Migration decisions and the gender dimensions of adverse climatic events. J. Rural Community Dev. 2015, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fruttero, A.; Halim, D.; Broccolini, C.; Coelho, B.; Gninafon, H.; Muller, N. Gendered impacts of climate change: Evidence from weather shocks. Environ. Res. Clim. 2024, 3, 045018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, H.; Lew, A.A. Livelihood resilience in tourism communities: The role of human agency. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, S.; Cohen, P.; McDougall, C.; Orirana, G.; Siota, F.; Doyle, K. Gender norms and relations: Implications for agency in coastal livelihoods. Marit. Stud. 2019, 18, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, M.; Weber, S.; Caron, C. Guide to participatory feminist research. In Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies; McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018; p. 44. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/43347231/Guide_to_Participatory_Feminist_Research_Abridged_Version_ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Goessling, K.P. Learning from feminist participatory action research: A framework for responsive and generative research practices with young people. Action Res. 2024, 23, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidzadeh, Z. Gender Research and Feminist Methodologies. In Gender-Competent Legal Education; Vujadinović, D., Fröhlich, M., Giegerich, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 183–213. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, H.; Divecha, S. Action methods for faster transformation: Relationality in action. Action Res. 2020, 18, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, M.; Torre, M.E. Critical participatory action research: A feminist project for validity and solidarity. Psychol. Women Q. 2019, 43, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A.V.; Peters, K.; Wilkinson, E.; Pichon, F.; Gray, K.; Tanner, T. The 3As Tracking Resilience Across BRACED; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2015; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Assessing Women’s Leadership in Disaster and Climate Resilience: Assessment Framework and Tools 2022. Available online: https://wrd.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/UNWomen%20Final%20Framework%20and%20Tools%20final.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Beckwith, L.; Warrington, S.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, T.; Greru, C.; Smith, G.; Minh, T.M.T.; Nguyen, L.; Hensengerth, O.; Woolner, P.; et al. Listening to Experiences of Environmental Change in Rural Vietnam: An Intergenerational Approach. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2023, 23, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainer, D. Mekong Delta Climate Resilient Agriculture Activity Design: Local Consultations Report; United States Agency for International Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/4477128/mekong-delta-climate-resilient-agriculture-activity-design/5274458/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mitsch, W.J. Modelling hydrological processes in created freshwater wetlands: An integrated system approach. Environ. Model. Softw. 2005, 20, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.B. Information systems and systems thinking: Time to unite? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 1988, 8, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.; Scholes, J. Soft Systems Methodology in Action; Wiley & Sons: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1999; p. 432. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Scognamillo, D.G.; Comer, C.E. Revealing community perceptions for ecological restoration using a soft system methodology. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2019, 32, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. Foreign: Read Data Stored by Minitab, S, SAS, SPSS, Stata, Systat, Weka, dBase,… R Package Version 0.8-59; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A. The Nature of Gender: Work, Gender, and Environment. Soc. Space 2006, 24, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschakert, P.; Machado, M. Gender Justice and Rights in Climate Change Adaptation: Opportunities and Pitfalls. Ethics Soc. Welf. 2012, 6, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, N.; Chaudhary, P.; Tiwari, P.R.; Yadaw, R.B. Institutional and Technological Innovation: Understanding Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change in Nepal. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A Conceptual Framework for Analyzing Adaptive Capacity and Multi-Level Learning Processes in Resource Governance Regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. In IDS Discussion Paper; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1991; Volume 296, p. 29. Available online: https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/Dp296.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, C.; Tan, R.; Cai, J. Measuring farmers’ sustainable livelihood resilience in the context of poverty alleviation: A case study from Fugong County, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yan, J.; Yang, L.E.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Lin, X. Linking smallholders’ livelihood resilience with their adaptation strategies to climate impacts: Insights from the Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Soc. 2024, 29, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; p. 292. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Governing natural resources: Institutional adaption and resilience. In Negotiating Environmental Change; Berkhout, F., Leach, M., Scoones, I., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2003; pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Deressa, T.T.; Hassan, R.M.; Ringler, C.; Alemu, T.; Yesuf, M. Determinants of farmers’ choice of adaptation methods to climate change in the Nile Basin of Ethiopia. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.B.; Lenhart, S.S. Climate change adaptation policy options. Clim. Res. 1996, 6, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J. Adapting to climate change in Pacific Island countries: The problem of uncertainty. World Dev. 2001, 29, 977–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, C.; Kyazze, F.; Naab, J.; Neelormi, S.; Kinyangi, J.; Zougmore, R.; Aggarwal, P.; Bhatta, G.; Chaudhury, M.; Tapoi-Bistram, M.-L.; et al. Understanding gender dimensions of agriculture and climate change in smallholder farming communities. Clim. Dev. 2016, 8, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.; Batung, E.; Kansanga, M.; Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H.; Luginaah, I. Livelihood diversification strategies and resilience to climate change in semi-arid northern Ghana. Clim. Change 2021, 164, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Alam, K.; Mushtaq, S.; Leal Filho, W. How do climate change and associated hazards impact on the resilience of riparian rural communities in Bangladesh? Policy implications for livelihood development. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinner, J.E.; Barnes, M.L. Social dimensions of resilience in social-ecological systems. One Earth 2019, 1, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, A.; Ayatullah, K.N.; Iqbal, S.; Abbas, S. Socio-Economic Constraints Affecting Sustainable Rural Livelihood. Arts Soc. Sci. J. 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylipaa, J.; Gabrielsson, S.; Jerneck, A. Climate change adaptation and gender inequality: Insights from rural Vietnam. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddika, Z. Women’s Livelihood Resilience and Adaptation Options for Climate Change. Master’s Thesis, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, J. Effects of disaster-related resettlement on the livelihood resilience of rural households in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aphane, M.; Dzivakwi, R.; Jacobs, P. Livelihood strategies of rural women in Eastern Cape and Limpopo. Agenda 2010, 24, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mittra, P.K. Livelihood diversification pursued by rural women farmer: The case of Bangladesh. J. Agric. Food Environ. 2021, 2, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidimoghadam, A.; PourSaeed, A.; Bijani, M.; Samani, R.E. Rural sustainable livelihood resilience to climate change: A strategic analysis. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 20, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.T.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Huynh, C.V.; Pham, T.H.; Schinkel, U. A nuanced analysis on livelihood resilience of Vietnamese upland households: An intersectional lens of ethnicity and gender. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, P.T.; Resurreccion, B.P. Women’s differentiated vulnerability and adaptations to climate-related agricultural water scarcity in rural Central Vietnam. Clim. Dev. 2014, 6, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaka, H.; Shava, E. Resilient rural women’s livelihoods for poverty alleviation and economic empowerment in semi-arid regions of Zimbabwe. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2018, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luftu-ul-Hasnaen, S.; Parvez, Z.; Syed, K. Empowering Rural Women through Skill Development: A Pathway to Sustainable Livelihoods. QJSS 2023, 4, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, K.E.; Buggy, L. Community-based climate change adaptation: A review of academic literature. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Al-Hassan, R.M.; Amarasinghe, O.; Fong, P.; Ocran, J.; Onumah, E.; Ratuniata, R.; Tuyen, T.V.; McGregor, J.A.; Mills, D.J. Is resilience socially constructed? Empirical evidence from Fiji, Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 38, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsatti, J.; Dinale, D. Livelihoods, work, women and climate change: Women’s voice in just transition. Labour Ind. 2024, 34, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Customer | Rural agrarian women, who are the primary beneficiaries and most affected by climate change and adaptation interventions. |

| Actors | Women’s associations, local governments, neighbors, provincial authorities, and central agencies, who directly implement or mediate support activities. |

| Transformations | Shifts toward greater household livelihood resilience through financial aid, peer advice, and social learning. |

| Worldviews | A widely held recognition that transformation is needed for stable livelihoods. |

| Owners | Local government officials, husbands and male relatives, and neighbors, who influence or control key adaptation decisions. |

| Environmental Constraints | Limited climate knowledge, difficulty identifying livelihood challenges, and restrictive gender norms limiting decision-making. |

| Supporter | Soc Trang (n = 30) | An Giang (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Women’s associations | 5.54 | 5.00 |

| Local government | 3.88 | 4.59 |

| Neighbors | 4.04 | 4.41 |

| Provincial authorities | 1.35 | 3.00 |

| Central agencies | 1.12 | 3.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tran, T.T.N.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Ashton, E.C.; Aka, S.M. Support Needs of Agrarian Women to Build Household Livelihood Resilience: A Case Study of the Mekong River Delta, Vietnam. Climate 2025, 13, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13080163

Tran TTN, Nguyen TTN, Ashton EC, Aka SM. Support Needs of Agrarian Women to Build Household Livelihood Resilience: A Case Study of the Mekong River Delta, Vietnam. Climate. 2025; 13(8):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13080163

Chicago/Turabian StyleTran, Tran T. N., Tanh T. N. Nguyen, Elizabeth C. Ashton, and Sharon M. Aka. 2025. "Support Needs of Agrarian Women to Build Household Livelihood Resilience: A Case Study of the Mekong River Delta, Vietnam" Climate 13, no. 8: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13080163

APA StyleTran, T. T. N., Nguyen, T. T. N., Ashton, E. C., & Aka, S. M. (2025). Support Needs of Agrarian Women to Build Household Livelihood Resilience: A Case Study of the Mekong River Delta, Vietnam. Climate, 13(8), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13080163