Investigating the Gender-Climate Nexus: Strengthening Women’s Roles in Adaptation and Mitigation in the Sidi Bouzid Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

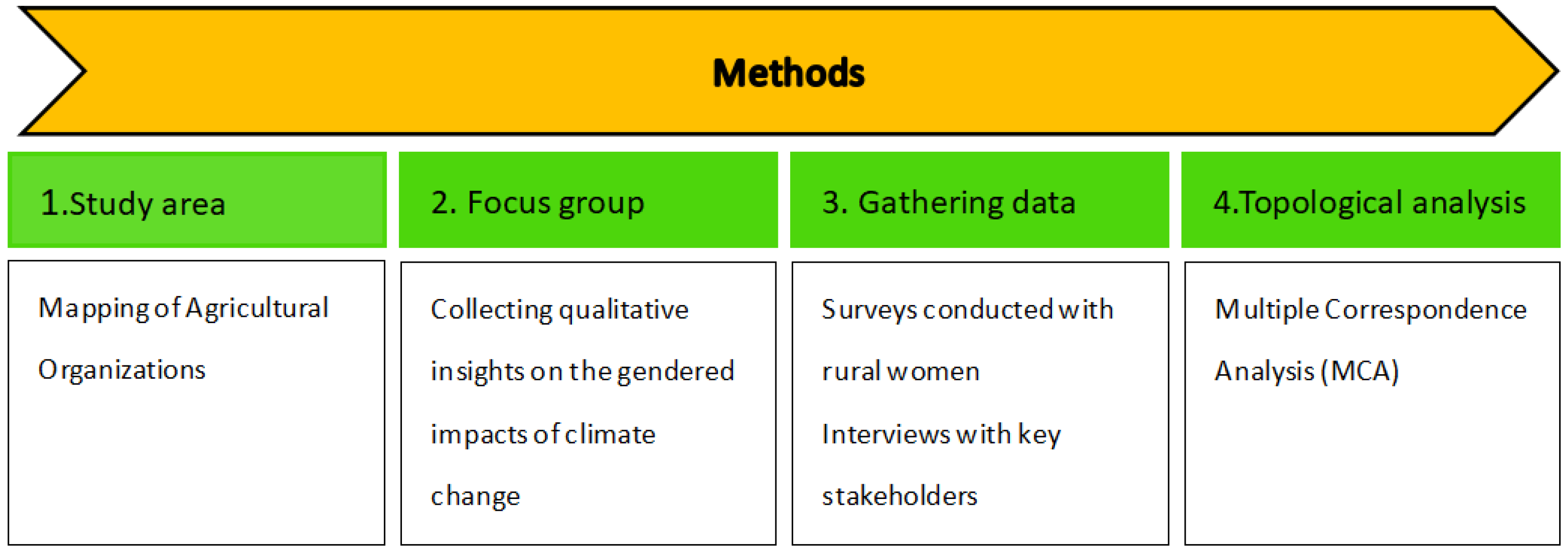

2. Research Methodology

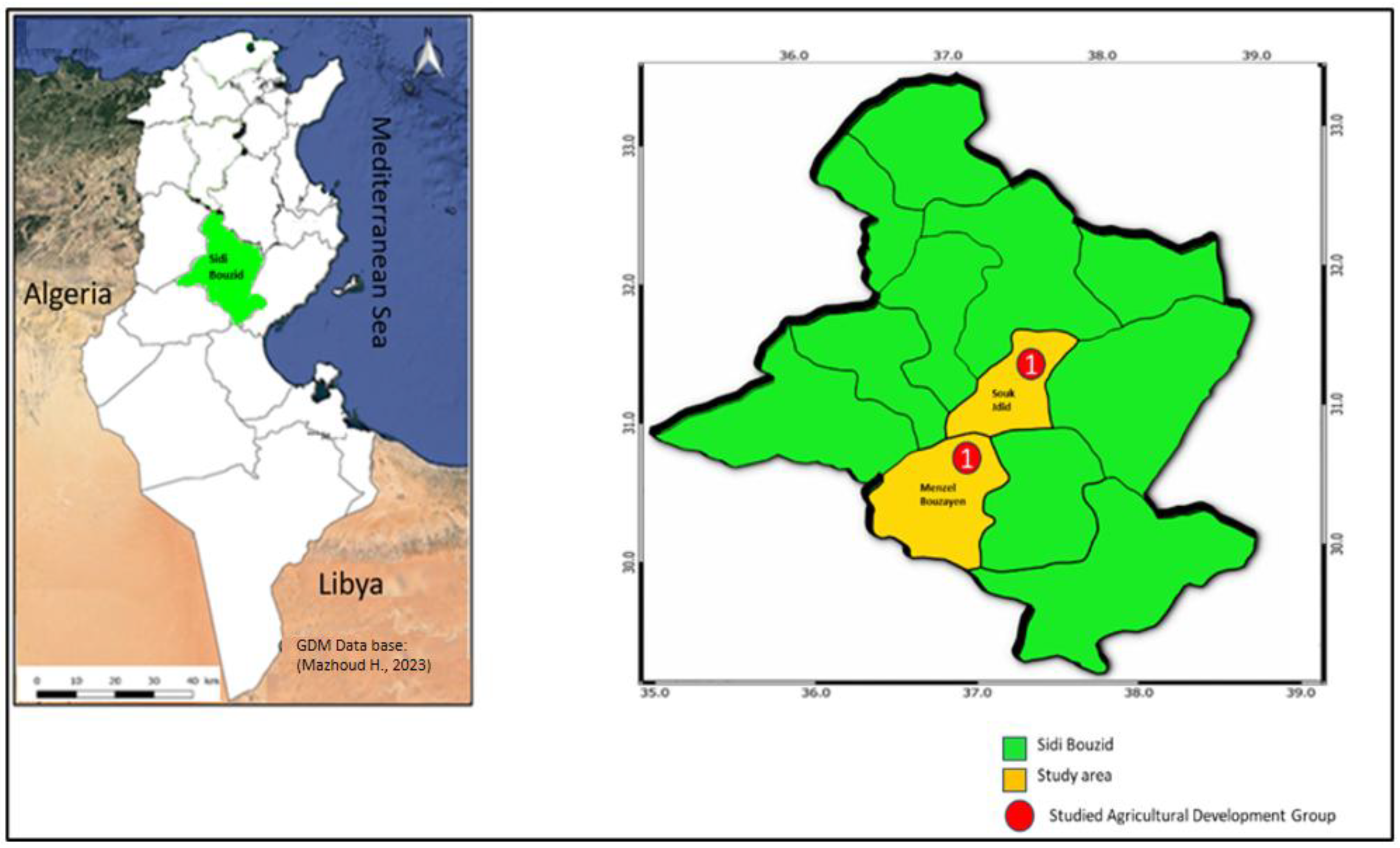

2.1. Mapping of Agricultural Organizations

2.2. Focus Group Discussions

2.3. Data Gathering

2.4. Analytical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

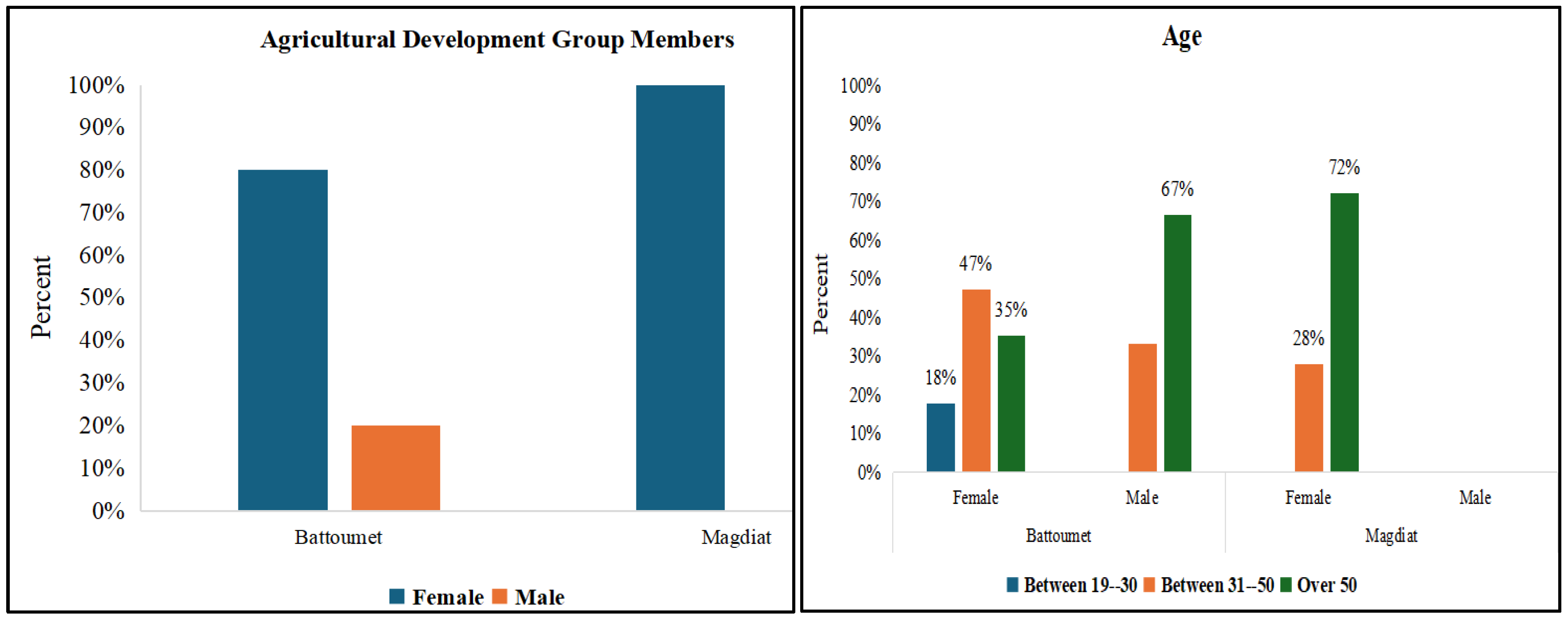

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Profile of Agricultural Development Group Members

3.1.2. Activities by Gender

3.1.3. Access to Water

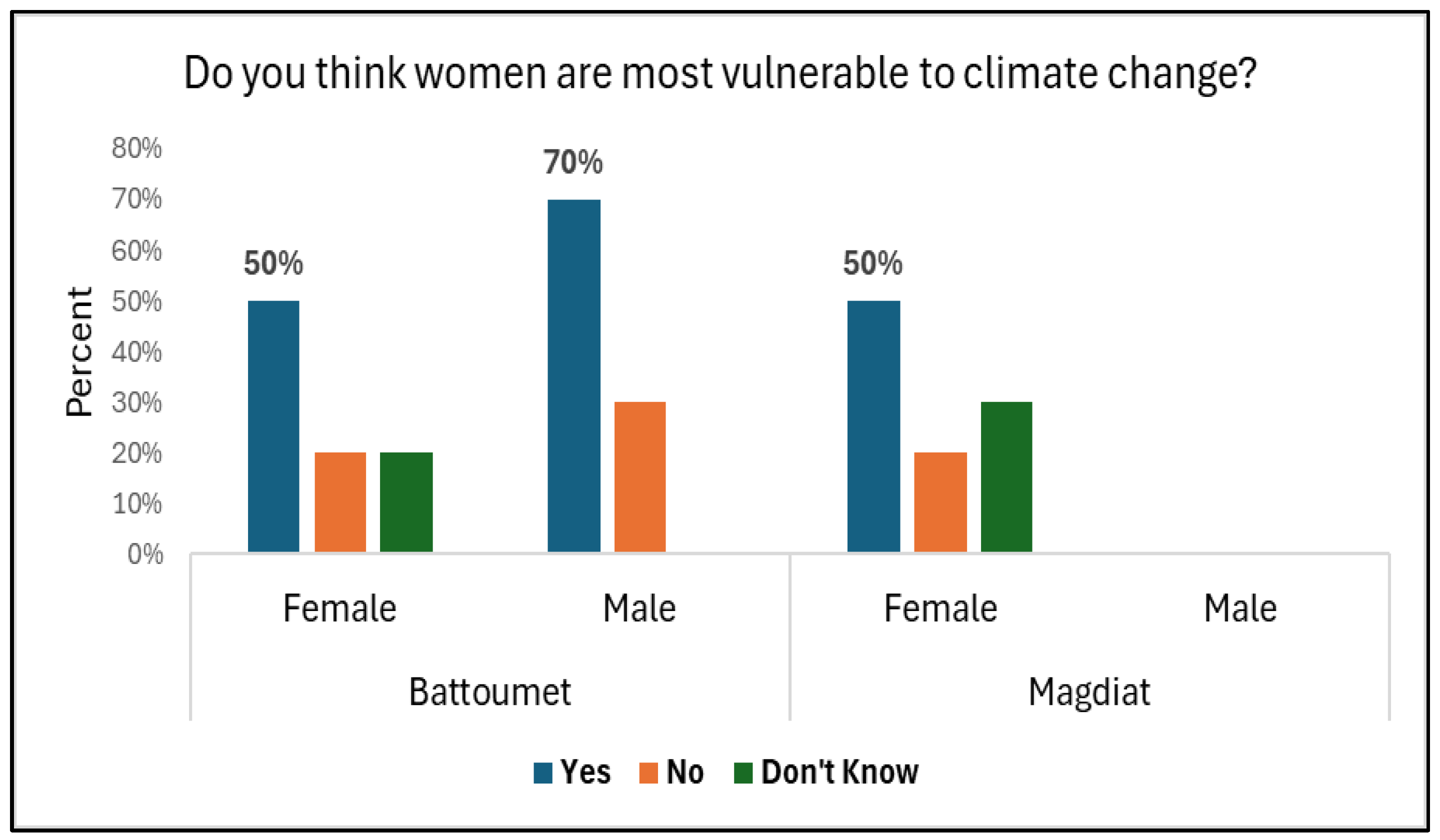

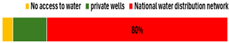

3.2. Gender Disparities in Climate Vulnerability

3.2.1. Rural Women’s Perception of Climate Change

3.2.2. Climate Change’s Impact on Rural Women

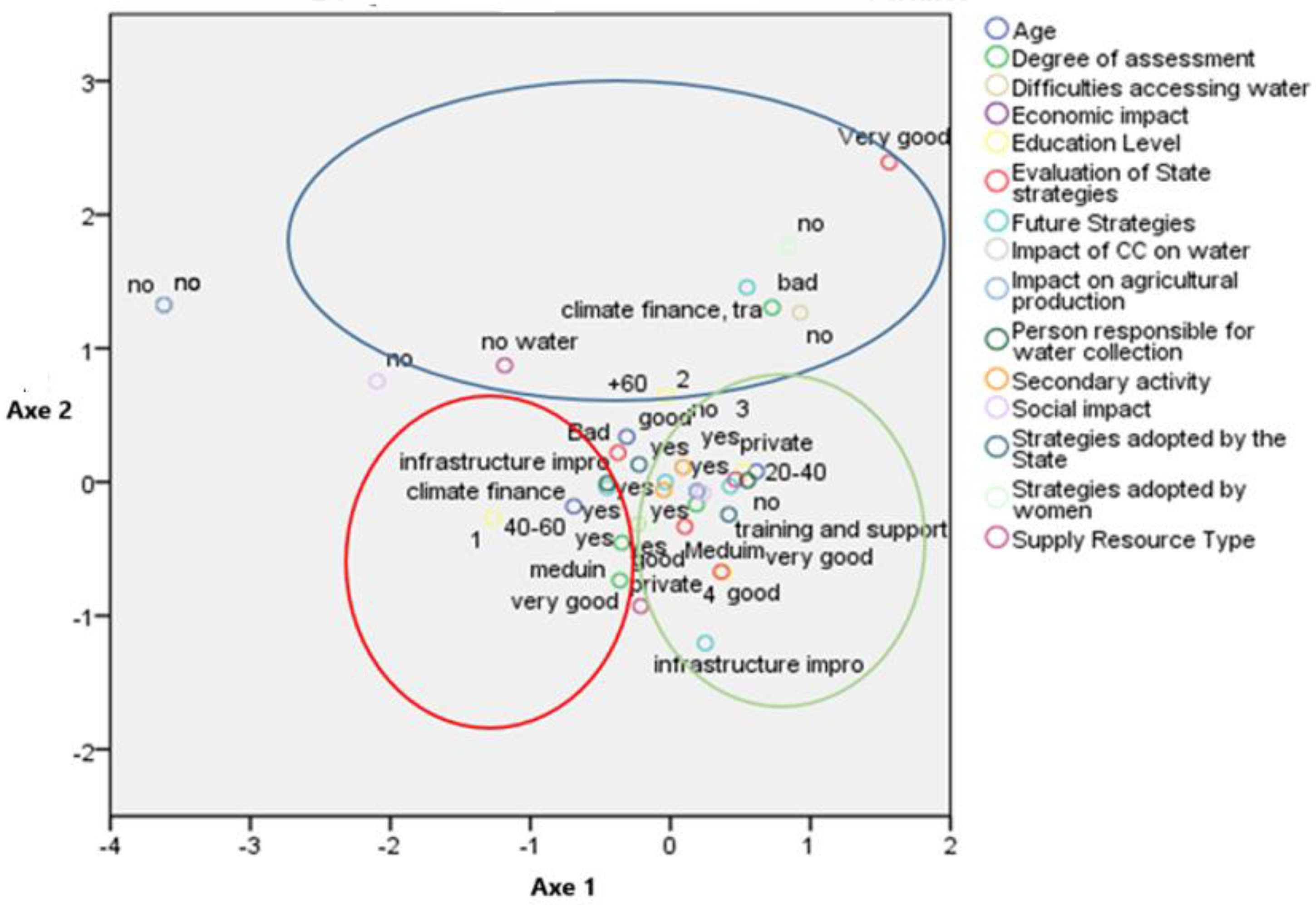

3.3. Analyzing Rural Women’s Vulnerability to Climate Change: The MCA Approach

3.3.1. Group1: Severely Vulnerable Women

3.3.2. Group 2: Vulnerable Women

3.3.3. Group 3: Adaptive Women

3.4. Strategies for Coping with Climate Change

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| G3CA | Gender Climate Change and Community Adaptation |

| INRAT | National Institute of Agronomic Research of Tunisia |

| INAT | National Agronomic Institute of Tunisia |

References

- World Bank. World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- The Food and Agriculture Organization. The State of Food and Agriculture—2010–2011. Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development. 2011. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i2050e/i2050e00.htm (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Amenyah, I.D.; Puplampu, K.P. Women in Agriculture: An Assessment of the Current State of Affairs in Africa; ACBF: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Njuki, J.; Eissler, S.; Malapit, H.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Bryan, E.; Quisumbing, A. A review of evidence on gender equality, women’s empowerment, and food systems. In Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; 165p. [Google Scholar]

- De Fraiture, C.; Molden, D.; Wichelns, D. Investing in water for food, ecosystems, and livelihoods: An overview of the comprehensive assessment of water management in agriculture. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.S.; Lal, R. Vulnerability of women to climate change in arid and semi-arid regions: The case of India and South Asia. J. Arid. Environ. 2018, 149, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oram, P.A. Sensitivity of agricultural production to climatic change, an update. In Climate and Food Security; IRRI: Manila, The Philippines, 1989; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.W. Realizing the potential benefits of climate prediction to agriculture: Issues, approaches, challenges. Agric. Syst. 2002, 74, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food Insecurity in the World; Food and Agricultural Organisation: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schwerhoff, G.; Konte, M. Gender and climate change: Towards comprehensive policy options. In Women and Sustainable Human Development; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020; pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OXFAM. Annual Report. 2015. Available online: https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/story/oxfam_annual_report_2015_-_2016_english_final_0.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- ONU Femmes. L’Autonomisation Economique: Quelques Faits et Chiffres. 2015. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/fr/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Chigbu, U. Rurality as a choice: Towards ruralising rural areas in subSaharan African countries. Dev. South. Afr. 2013, 30, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifabiyi, I.; Adedeji, A. Analysis of water poverty for irepodun local government area (Kwara state, Nigeria). Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 7, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sitko, N.; Cavatassi, R.; Stafferi, I.; Heesemann, E.; Rossi, J.M.; Valbuena, L.B.; Rajagopalan, P.; Kluth, J.; Azzarri, C. The Unjust Climate: Measuring the Impacts of Climate Change on Rural Poor, Women and Youth; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Labiadh, I. Patrimoine forestier et stratégie de développement territorial. Cas du groupement féminin de développement agricole GFDA Elbaraka dans le Nord-ouest de la Tunisie. In Valorisation des Savoir-Faire Productifs et Stratégies de Développement Territorial: Patrimoine, Mise en Tourisme et Innovations Sociales; Grison, J.B., Rieutort, L., Eds.; Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal: Saugues, France, 2014; 14p, Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01216828/document (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Hanafi, A.; Mazhoud, H.; Chemak, F.; Faysse, N.; Kharroubi, F. Women’s development organisations in rural areas of Tunisia: Rethinking support to strengthen their autonomy. Cah. Agric. 2024, 33, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CREDIF. Genre et Changement Climatique: Une Vision Différente. 2015. Available online: https://www.cilg-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/La-Revue-du-CREDIF-n54-FR.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Naoum, R.F. Bridging the Gender Gap: Mitigating the Impacts of Climate Change on Women in MENA with a Focus on the Agriculture Sector. In Sustainability Can’t Wait! VII. BBU International Sustainability Student Conference Proceeding; Budapesti Gazdasági Egyetem: Budapest, Hungary, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Md, A.; Gomes, C.; Dias, J.M.; Cerdà, A. Exploring gender and climate change nexus, and empowering women in the south western coastal region of Bangladesh for adaptation and mitigation. Climate 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afi, M. Resilience Assessment of Social-Ecological Systems in MENA Region: An Application of Tri-Capital Framework in Jordan, Tunisia Morocco. Master’s Thesis, University College Cork, Madrid, Spain, 2018. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11766/9502 (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Heni, F.; Dhieb, M. Les disparités socio-économiques dans le gouvernorat de Sidi Bouzid (centre ouest de la Tunisie). Études Caribéennes 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazier, H.; Ezzat, A. Gender diferences and time allocation: A comparative analysis of Egypt and Tunisia. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 85, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Fry, H.; Shrestha, N.; Costello, A.; Saville, N.M. Determinants of intra-household food allocation between adults in South Asia—A systematic review. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amroussia, N.; Goicolea, I.; Hernandez, A. Reproductive health policy in Tunisia: Women’s right to reproductive health and gender empowerment. Health Hum. Rights 2016, 18, 183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Institut National de la Statistique (INS). Recensement Général de la Population et de L’habitat. 2014. Available online: https://www.ins.tn/enquetes/recensement-general-de-la-population-et-de-lhabitat-2014 (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Abebe, T.; Bekele, L.; Hessebo, M.T. Assessment of Future Climate Change Scenario in Halaba District, Southern Ethiopia. Atmos. Clim. Sci. 2022, 12, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women Watch. Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change. 2022. Available online: www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/factsheet.html (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Terefe, B.; Jembere, M.M.; Assimamaw, N.T. Access to drinking safe water and its associated factors among households in East Africa: A mixed effect analysis using 12 East African countries recent national health survey. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, G.; Calow, R.; Macdonald, A.; Bartram, J. Climate change and water andsanitation: Likely impacts and emerging trends for action. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NM, Q. A method for measuring women climate vulnerability: A case study in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 14, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.; Li, R.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Chen, B. Income diversification: A strategy for rural region risk management. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, M.; Hayati, D. Identifying strategies for adaptation of rural women to climate variability in water scarce areas. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1177684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, Z.; Abid, M.; Zafar, Q.; Mehmood, S. Detrimental effects of climate change on women. Earth Syst. Environ. 2018, 2, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchama, N.; Ferrant, G.; Fuiret, L.; Meneses, A.; Thim, A. Gender Inequality in West African Social Institutions; West African Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Women Watch. Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change. 2009. Available online: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/downloads/Women_and_Climate_Change_Factsheet.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Chandra, A.; McNamara, K.E.; Dargusch, P.; Caspe, A.M.; Dalabajan, D. Gendered vulnerabilities of smallholder farmers to climate change in conflict-prone areas: A case study from Mindanao, Philippines. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 50, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsemolu, A.A.; Olukoya, O.A. The vulnerability of women to climate change in coastal regions of Nigeria: A case of the Ilaje community in Ondo State. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbami, C.A.O. Climatepreneurship: Adaptation Strategy for Climate Change Impacts on Rural Women Entrepreneurship Development in Nigeria. In African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 2143–2168. [Google Scholar]

- Mulema, A.A.; Cramer, L.; Huyer, S. Stakeholder engagement in gender and climate change policy processes: Lessons from the climate change, agriculture and food security research program. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 862654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

| Categories | Indicators | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics | Age | The classification that has been provided provided helps to segment women into different age groups to better understand how water scarcity affects them differently. These age categories allow for a more nuanced analysis of their experiences, vulnerabilities, and coping mechanisms related to water issues [28]. Here is a summary of each group: -Younger Women (19–30 years); -Middle-Aged Women (31–49 years); -Older Women (50+ years); |

| Education level | This variable refers to the highest level of formal schooling or vocational training attained by the women in this study. Understanding the education level of participants helps to identify potential gaps in knowledge and the need for targeted educational interventions to strengthen women’s roles in climate adaptation and mitigation [29]. | |

| Dependence on natural resource | Access to water | This variable refers to the availability and proximity of safe, clean water sources for households in the Sidi Bouzid region. This variable is critical in understanding women’s vulnerability to water scarcity, as access directly impacts daily livelihoods, health, and adaptation strategies. Limited access to water often exacerbates women’s roles in water collection and management, heightening their exposure to climate risks [29]. |

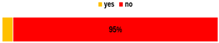

| Water insecurity | This variable refers to the inconsistent or unreliable availability of sufficient water for drinking, sanitation, agriculture, and other daily needs [30] | |

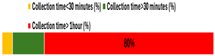

| Water collection labor | This variable describes water collection labor among women. it involves the time and physical effort spent by women and households in gathering water, often from distant or unreliable sources. It also involves participation in community decision-making related to climate adaptation [31]. | |

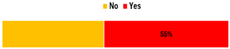

| Economic | Lack of income diversification | This variable refers to the limited variety of income sources available to households, particularly for women in the Sidi Bouzid region. This economic vulnerability is exacerbated in contexts of water scarcity, as reliance on a single income stream—often linked to agriculture or natural resource-based activities—leaves households highly susceptible to climate shocks. Without access to alternative livelihoods, women face increased financial insecurity and reduced capacity to adapt to the impacts of water stress, hindering their roles in climate adaptation and mitigation strategies [32]. |

| Social | Women’s roles, and access to support | Social vulnerability in this context is shaped by the intersection of family stress, gendered roles, and limited institutional and community support. Women, particularly those in rural areas, face significant family conflicts and stress due to the burdens of water collection and the economic impacts of water scarcity [31]. |

| Activity | Task/Responsibility of Men | Task/Responsibility of Women |

|---|---|---|

| Water Collection | -Generally, they do not participate in this activity. | -They bear the primary responsibility for water collection (water fetching), which is physically demanding and essential for the well-being and survival of families and communities. |

| Processing and sale of local products (thyme, rosemary, harissa, etc.) | -Do not participate. | -Responsible for the collection, processing, and sale of non-timber forest products within the GAEC. -They process vegetables and fruits into traditional products such as harissa, date syrup, and pomegranate syrup for Aoula. |

| Work on agricultural holdings | -Heads of operations: manage and plan agricultural activities, control resources, and make decisions regarding crop selection, irrigation planning, etc. | -A minority of women hold the position of head of operations. -Specific responsibility: women are primarily responsible for harvesting crops such as olives, tomatoes, and peppers, often under difficult working conditions and at very low prices. |

| Childcare and education | -Men make decisions regarding children’s education, but the day-to-day responsibility remains with women. | -Women are responsible for paying school fees, taking care of the sick, taking family members to the doctor, and buying medications. |

| Harvesting of forest products | -Do not participate in this activity. | -Have access to forests but do not control the forests or make decisions regarding them. -Responsible for harvesting non-timber forest products. |

| Battoumet | Magdiat | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Local practices | 8 | 27 | 4 | 13 | 12 | 40 |

| Neighbors and group members | 3 | 10 | 6 | 20 | 9 | 30 |

| Media platforms | 6 | 20 | - | - | 6 | 20 |

| Non governemental organizations | 3 | 10 | - | - | 3 | 10 |

| Indicators | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age |  |  |  |

| Education level |  |  |  |

| Access to water |  |  |  |

| Water collection labor (collection time) |  |  |  |

| Income diversification |  |  |  |

| Women’s access to support |  |  |  |

| Strategy Name | Kind of Stakeholders | Outputs and Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation of international projects (TWIZA, ACESS, G3CA) | Civil society, rural women’s District, Ministry of agriculture and INRAT | -Enhancement of women’s access to climate finance. -Enhancement of market access -Increase in women’s earnings. |

| Use research products to build scientific credibility | INRAT, civil society | -Development of research papers, policy papers and policy briefs that have increased policymakers’ commitment to integrating gender into climate change policies and actions. -Development guidelines for gender integration in climate change strategy |

| Co-learning and co-production of knowledge | INRAT, INAT, ministry of agriculture | -The National Institute of Agricultural Research of Tunisia (INRAT) in collaboration with APEDDUB had already been implementing some projects (G3CA) that included gender capacity building. -Another capacity-building event was organized to deepen rural women’s understanding of the impacts of climate change and the solutions they can adopt. Development of a Best Practices Guide |

| Development of partenership and international alliance | SSN, WWF, Hivos, INRAT, medias, ministry of agriculture | -Building alliances, exchanging information and coordinating, with invisible stakeholder were highly influential in the implementation of an intervention |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazhoud, H.; Boucif, A.; Ouhibi, A.; Hajji-Hedfi, L.; Chemak, F. Investigating the Gender-Climate Nexus: Strengthening Women’s Roles in Adaptation and Mitigation in the Sidi Bouzid Region. Climate 2025, 13, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13080164

Mazhoud H, Boucif A, Ouhibi A, Hajji-Hedfi L, Chemak F. Investigating the Gender-Climate Nexus: Strengthening Women’s Roles in Adaptation and Mitigation in the Sidi Bouzid Region. Climate. 2025; 13(8):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13080164

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazhoud, Houda, Arij Boucif, Abir Ouhibi, Lobna Hajji-Hedfi, and Fraj Chemak. 2025. "Investigating the Gender-Climate Nexus: Strengthening Women’s Roles in Adaptation and Mitigation in the Sidi Bouzid Region" Climate 13, no. 8: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13080164

APA StyleMazhoud, H., Boucif, A., Ouhibi, A., Hajji-Hedfi, L., & Chemak, F. (2025). Investigating the Gender-Climate Nexus: Strengthening Women’s Roles in Adaptation and Mitigation in the Sidi Bouzid Region. Climate, 13(8), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13080164