The New IGRICE Model as a Tool for Studying the Mechanisms of Glacier Retreat

Abstract

1. Introduction

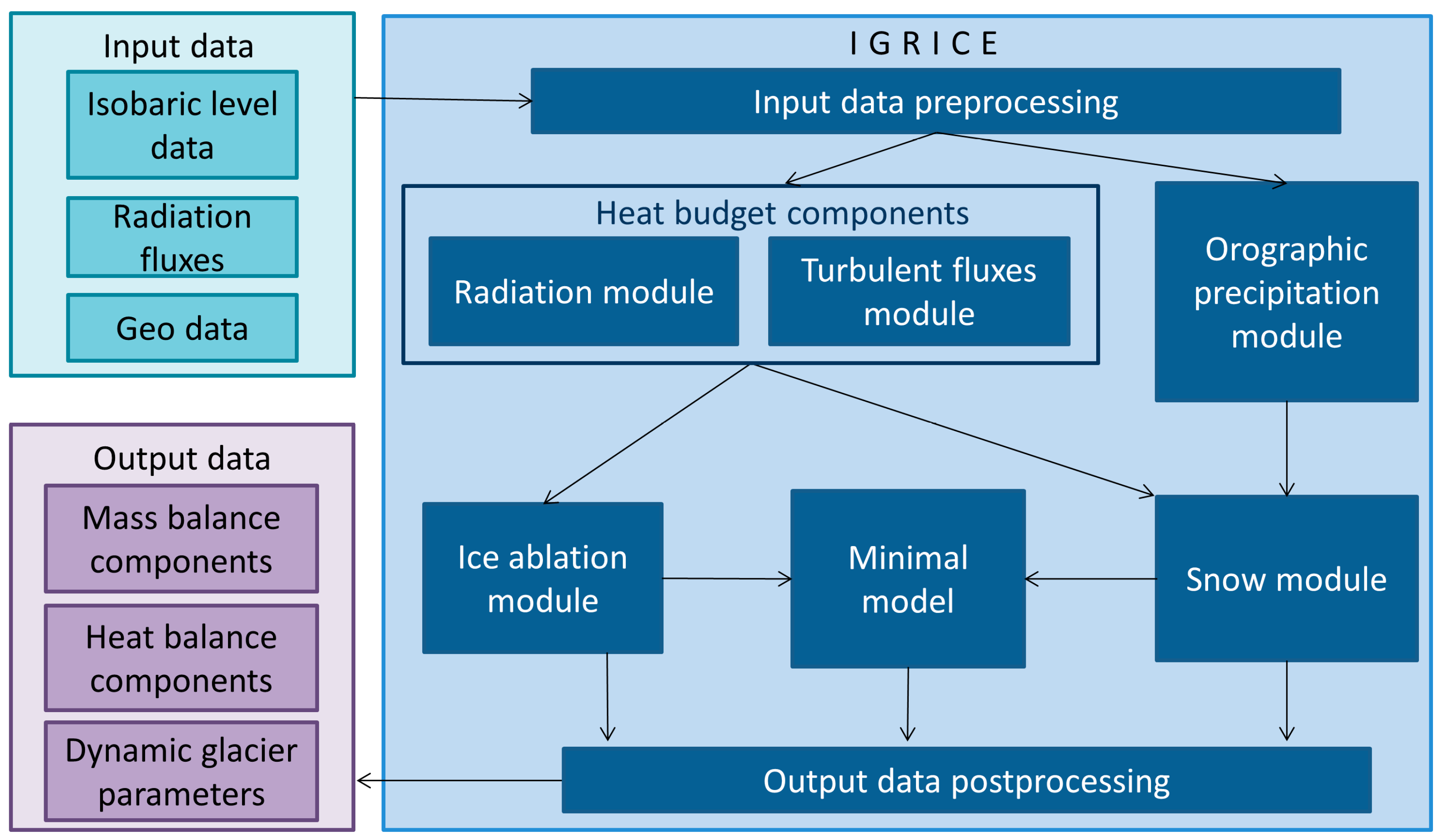

2. IGRICE Model Description

2.1. General Scheme of the Model

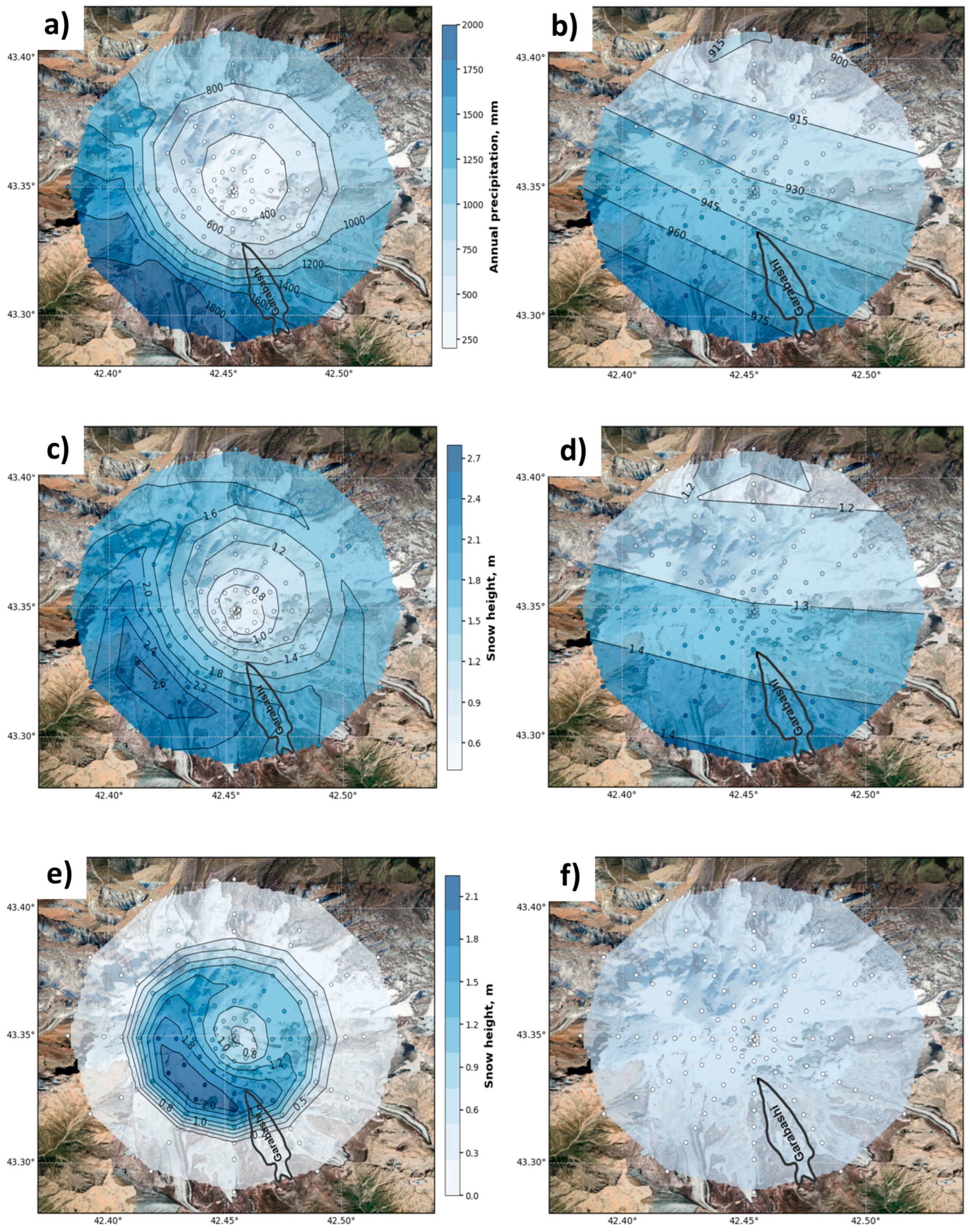

2.2. Orographic Precipitation

2.3. Snow-Cover Model

2.4. Energy Fluxes

2.5. Ice Ablation Module

2.6. Some Other Parametrizations

3. Selected Glaciers and Model Set-Up

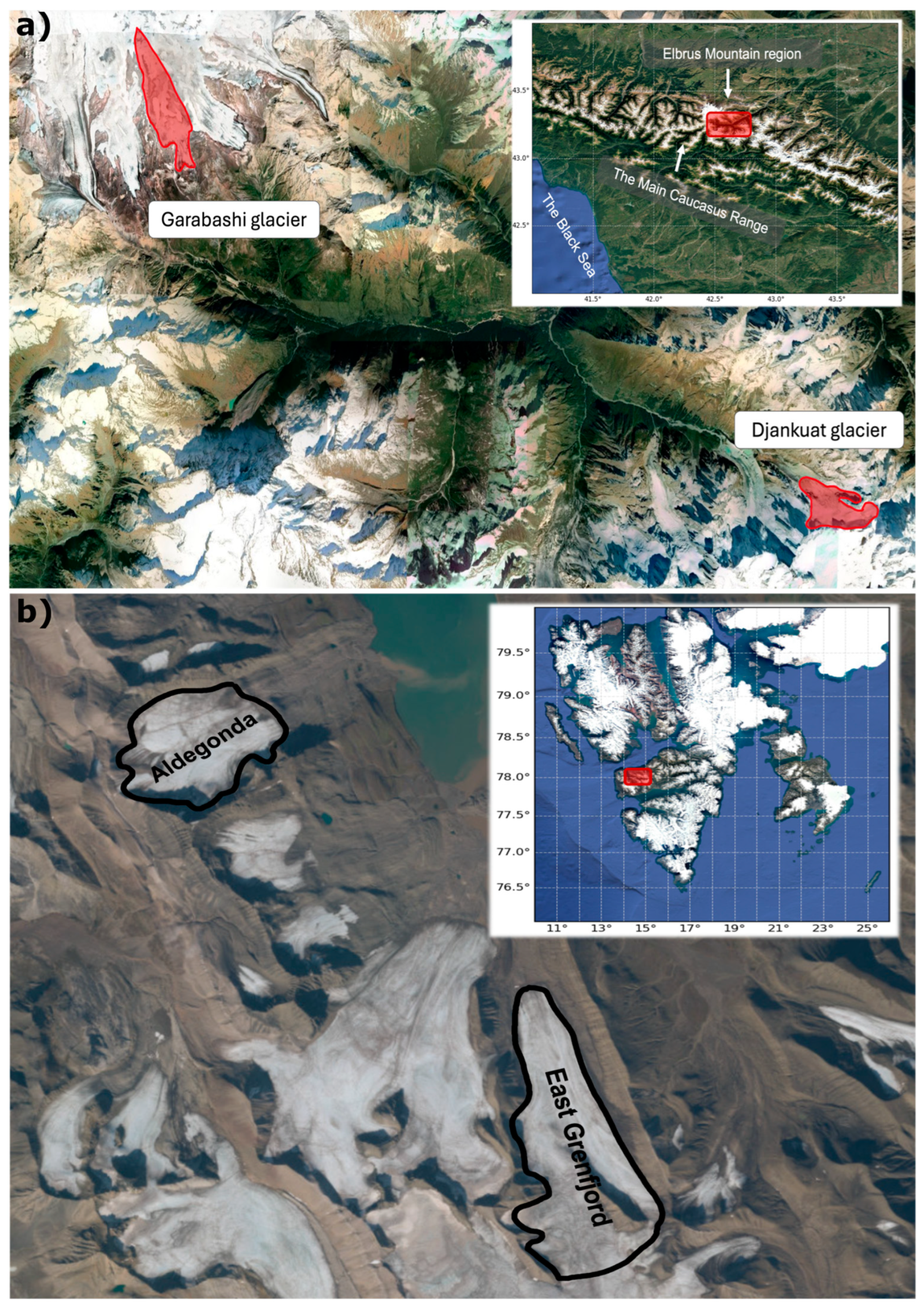

3.1. Selected Glaciers

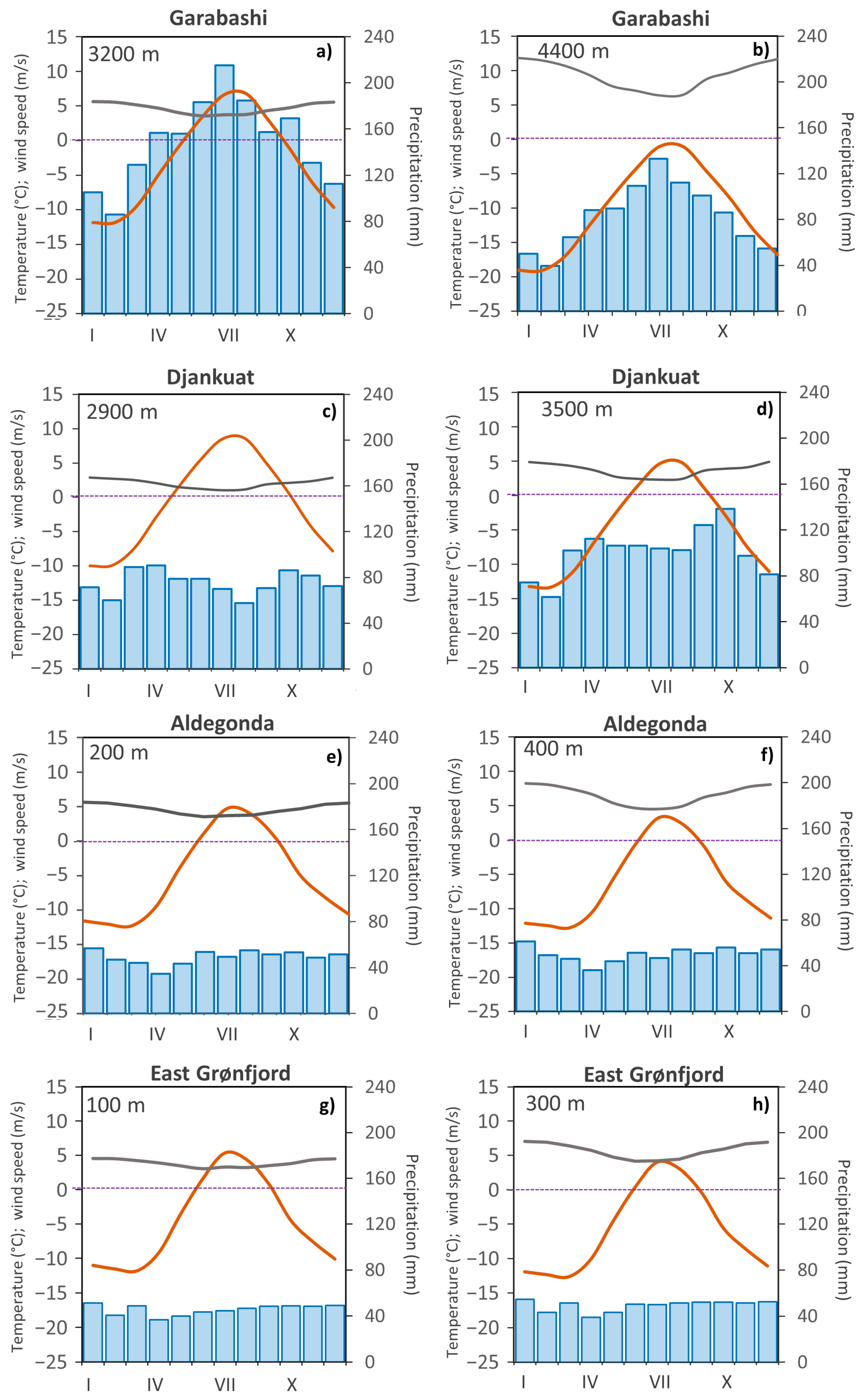

3.2. Description of Model Setup and Input Data

- Integration period: 1983–2021, time step of 3 h. The first year was not analyzed (model spin-up period). Annual mass balance was calculated at the end of the glaciological (mass balance) year, which for the Caucasus glaciers was taken as October 1, and for the Svalbard glaciers as September 1.

- Input data: ERA5 reanalysis data (spatial resolution 0.25°) with a 3-h time step for the grid cell containing the glacier. The quality of ERA5 and its predecessor ERA-Interim for temperature and wind speed has been frequently evaluated for mountain regions, including the Caucasus, based on comparisons with meteorological measurements on glaciers (e.g., [30,63]). Satisfactory data quality for temperature and wind speed has been shown. In the Arctic, ERA5 also agrees reasonably well with observations at weather stations, though wind speed and relative humidity are reproduced worse than temperature and shortwave radiation [64].

- Topography data within the reanalysis grid cell used for the studied glaciers were obtained from processing the ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM 3) [67] with a spatial resolution of 30 m (in a rectangular coordinate system). The same DEM was used to compute elevation angles for each of the altitudinal zones.

3.3. Selecting Some Model Parameters

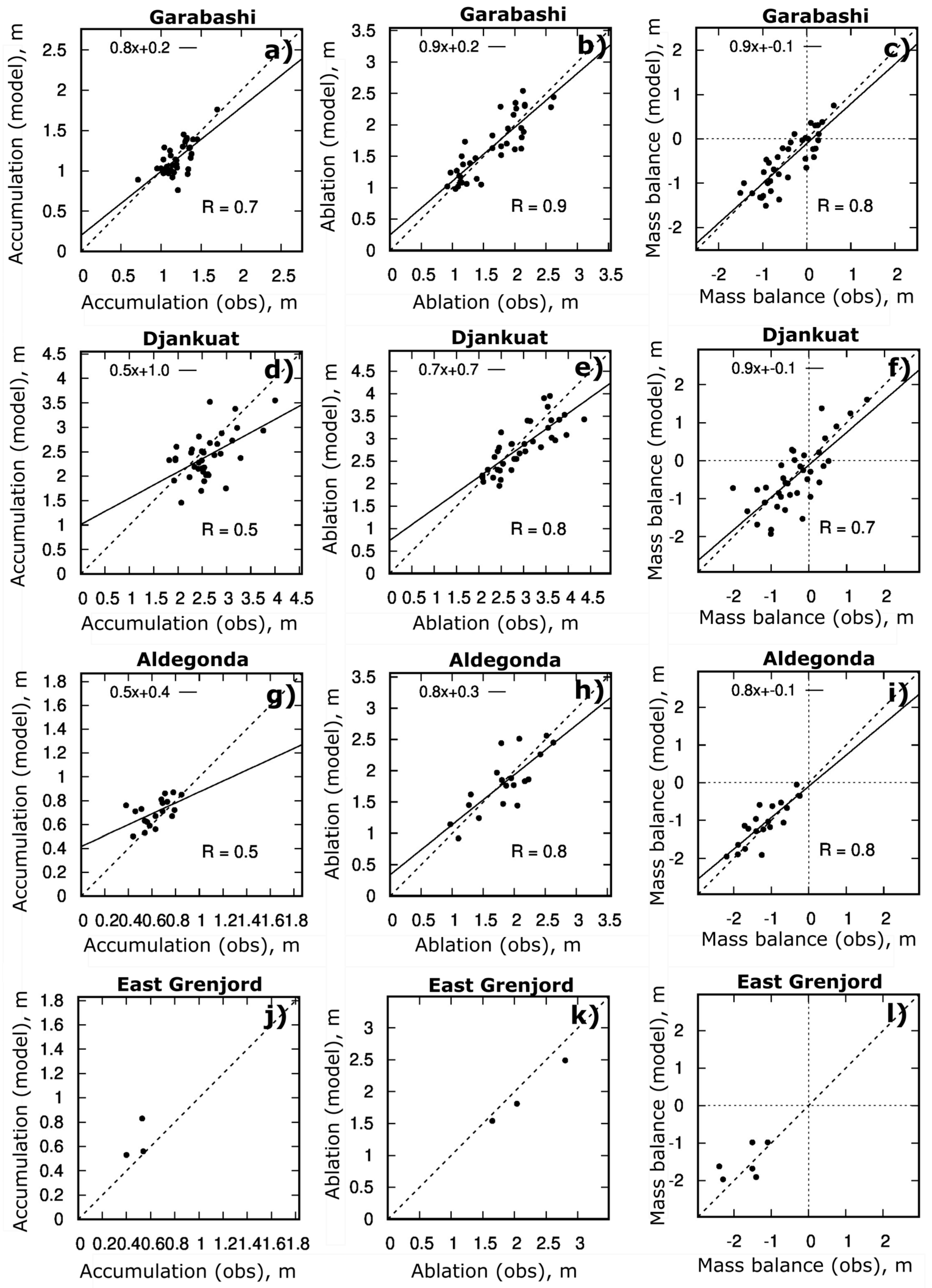

4. Results and Discussion

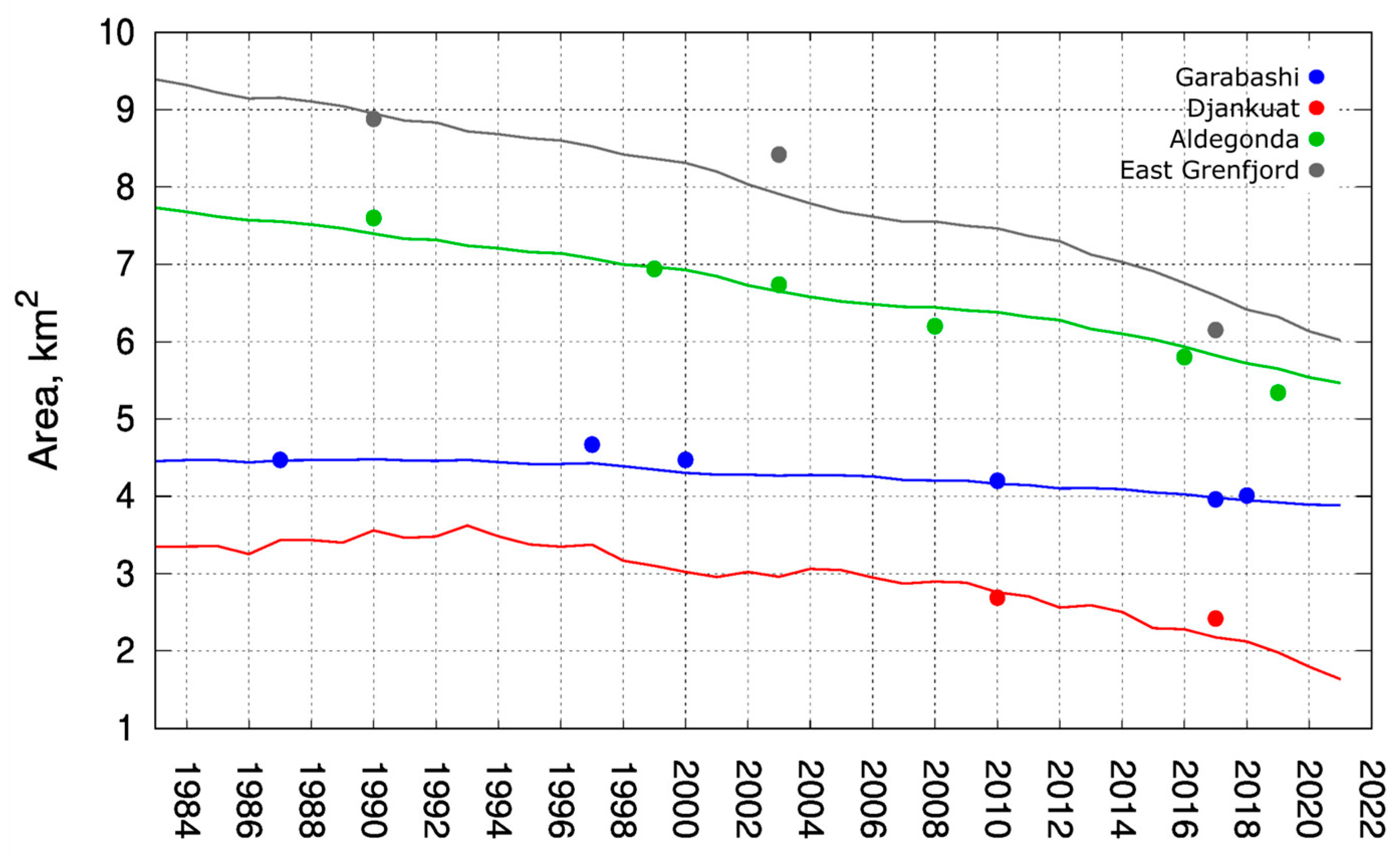

4.1. Mass Balance and Glacier Dynamics

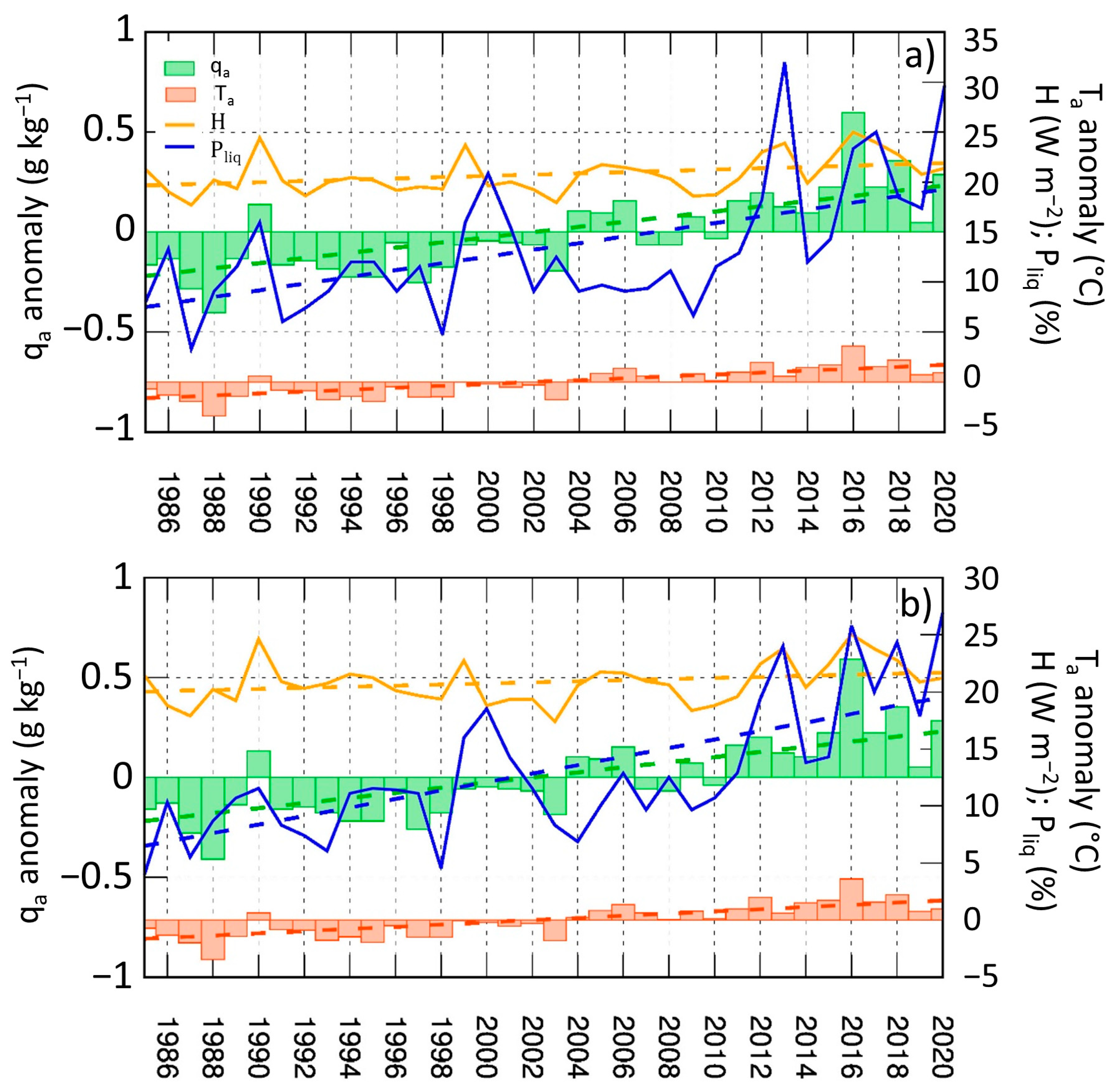

4.2. Mechanisms of Glacier Degradation

5. Prospects for the IGRICE Model Development

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doganovsky, A.M. Land Hydrology (General Course); Russian State Hydrometeorological University: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2012; 524p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Huss, M.; Hock, R. Global-scale hydrological response to future glacier mass loss. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rets, E.; Khomiakova, V.; Kornilova, E.; Ekaykin, A.; Kozachek, A.; Mikhalenko, V. How and when glacial runoff is important: Tracing dynamics of meltwater and rainfall contribution to river runoff from headwaters to lowland in the Caucasus mountains. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorg, A.; Bolch, T.; Stoffel, M.; Solomina, O.; Beniston, M. Climate change impacts on glaciers and runoff in Tien Shan (Central Asia). Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhupankhan, A.; Tussupova, K.; Berndtsson, R. Water in Kazakhstan, a key in Central Asian water management. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2018, 63, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, M.; Hock, R. A new model for global glacier change and sea-level rise. Front. Earth Sci. 2015, 3, 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, T.E.; Miles, E.S.; McCarthy, M.; Buri, P.; Guyennon, N.; Salerno, F.; Carturan, L.; Brock, B.; Pellicciotti, F. Mountain glaciers recouple to atmospheric warming over the twenty-first century. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 15, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerlemans, J. Minimal Glacier Models; Igitur: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; 91p. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstykh, M.A.; Fadeev, R.Y.; Shashkin, V.V.; Goyman, G.S. Improving the Computational Efficiency of the Global SL-AV Numerical Weather Prediction Model. Supercomput. Front. Innov. 2021, 8, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlarski, S.; Jacob, D.; Podzun, R.; Frank, P. Representing glaciers in a regional climate model. Clim. Dyn. 2010, 34, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Ganopolski, A.; Chen, F.; Claussen, M.; Wang, H. Impacts of snow and glaciers over Tibetan Plateau on Holocene climate change: Sensitivity experiments with a coupled model of intermediate complexity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, 360–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.Z.; Georges, D.; Rabatel, A.; Randin, C.F.; Renaud, J.; Delestrade, A.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Choler, P.; Thuiller, W. Accounting for tree line shift, glacier retreat and primary succession in mountain plant distribution models. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, S.C.B.; Braithwaite, R.J. Glacier volume response time and its links to climate and topography based on a conceptual model of glacier hypsometry. Cryosphere 2009, 3, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, K. The application of the shallow-ice approximation. Theor. Glaciol 1983, 1, 256–332. [Google Scholar]

- Zekollari, H.; Huss, M.; Farinotti, D.; Lhermitte, S. Ice-Dynamical Glacier Evolution Modeling—A Review. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postnikova, T.N.; Rybak, O.O. Global glaciological models: A new stage in the development of methods for predicting glacier evolution. Part 1. General approach and model architecture. Ice Snow 2021, 62, 620–636. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, O.O.; Rybak, E.A.; Kutuzov, S.S.; Lavrentyev, I.I.; Morozova, P.A. Calibration of the mathematical model of the dynamics of the Marukh glacier, Western Caucasus. Ice Snow 2015, 55, 9–20. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reichert, B.K.; Bengtsson, L.; Oerlemans, J. Recent glacier retreat exceeds internal variability. J. Clim. 2002, 15, 3069–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, D.; Walter, A.; Zumbuhl, H.J. The application of a non-linear back-propagation neural network to study the mass balance of Grosse Aletschgletscher, Switzerland. J. Glaciol. 2005, 51, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, R. Temperature index melt modelling in mountain areas. J. Hydrol. 2003, 282, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, A. Physical basis for the temperature-based melt-index method. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2001, 40, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheler, B.A.; Flowers, G.E. Glacier subsurface heat-flux characterizations for energy-balance modeling in the Donjek Range, southwest Yukon, Canada. J. Glaciol. 2011, 57, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, A.H.; Flowers, G.E. Spatial and temporal transferability of a distributed energy-balance glacier melt-model. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 1480–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano Gacha, M.F.; Koch, M. Distributed Energy Balance Flux Modelling of Mass Balances in the Artesonraju Glacier and Discharge in the Basin of Artesoncocha, Cordillera Blanca, Peru. Climate 2021, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorova, U.; Terekhov, A.; Ivanov, B.; Demidov, V. Heat balance of a low-elevated Svalbard glacier during the ablation season: A case study of Aldegondabreen. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2023, 55, 2190057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagina, N.; Kutuzov, S.; Rets, E.; Smirnov, A.; Chernov, R.; Lavrentiev, I.; Mavlyudov, B. Mass balance of Austre Grønfjordbreen, Svalbard, 2006–2020, estimated by glaciological, geodetic and modeling approaches. Geosciences 2021, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, M.; Liston, G.E.; Strasser, U.; Zängl, G.; Schulz, K. High resolution modelling of snow transport in complex terrain using downscaled MM5 wind fields. Cryosphere 2010, 4, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayand, N.E.; Marsh, C.B.; Shea, J.M.; Pomeroy, J.W. Globally scalable alpine snow metrics. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 213, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudiger, D.; Kohn, I.; Seibert, J.; Stahl, K.; Weiler, M. Snow redistribution for the hydrological modeling of alpine catchments. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2017, 4, e1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toropov, P.A.; Debol’skii, A.V.; Polyukhov, A.A.; Shestakova, A.A.; Popovnin, V.V.; Drozdov, E.D. Oerlemans minimal model as a possible instrument for describing mountain glaciation in earth system models. Water Resour. 2023, 50, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.G. Mountain Weather and Climate, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; 506p. [Google Scholar]

- Toropov, P.A.; Shestakova, A.A.; Yarinich, Y.I.; Kutuzov, S.S. Modeling Orographic Precipitation Using the Example of Elbrus. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2023, 59, S8–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M.R. A Diagnostic Model for Estimating Orographic Precipitation. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1994, 33, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, Y.L.; Farley, R.D.; Orville, H.D. Bulk parameterization of the snow field in a cloud model. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1983, 22, 1065–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushintsev, I.M.; Drozdov, E.D.; Toropov, P.A.; Mikhalenko, V.N.; Vorobiev, M.A.; Hayredinova, A.G. Modeling of snow cover on glaciers of the Caucasus and Kamchatka Peninsula. Ice Snow 2025, 65, 21–36. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Elagina, N.; Rets, E.; Korneva, I.; Toropov, P.; Lavrentiev, I. Simulation of mass balance and glacial runoff of Mount Elbrus from 1984 to 2022. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2025, 70, 1929–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.Y.; Yang, Z.L.; Mitchell, K.E.; Chen, F.; Ek, M.B.; Barlage, M.; Kumar, A.; Manning, K.; Niyogi, D.; Rosero, E.; et al. The Community Noah Land Surface Model with Multiparameterization Options (Noah-MP): 1. Model Description and Evaluation with Local-Scale Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011, 116, D12109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRF v. 4.1.2 Source Code. Available online: https://github.com/wrf-model/WRF/releases/tag/v4.1.2 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Turkov, D.V.; Drozdov, E.D.; Lomakin, A.A. Snow albedo and its parameterization for the purposes of modeling natural systems and climate. Izv.—Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2024, 60, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerlemans, J.; Greuell, W. Sensitivity studies with a mass balance model including temperature profile calculations inside the glacier. Z. Für Gletscherkunde Glazialgeol. 1986, 22, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Abolafia-Rosenzweig, R.; He, C.; McKenzie Skiles, S.; Chen, F.; Gochis, D. Evaluation and optimization of snow albedo scheme in Noah-MP land surface model using in situ spectral observations in the Colorado Rockies. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2022, 14, e2022MS003141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grachev, A.A.; Andreas, E.L.; Fairall, C.W.; Guest, P.S.; Persson, P.O.G. SHEBA flux-profile relationships in the stable atmospheric boundary layer. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2007, 124, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M.D.; Scherer, D. A grid-and subgrid-scale radiation parameterization of topographic effects for mesoscale weather forecast models. Mon. Weather Rev. 2005, 133, 1431–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezval, E.I.; Chubarova, N.E.; Gröbner, J.; Ohmura, A. Influence of atmospheric parameters on long-wave downward radiation and features of its regime in Moscow. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2012, 48, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhalenko, V.N.; Kutuzov, S.S.; Lavrentyev, I.I.; Toropov, P.A.; Abramov, A.A.; Aleshina, M.A.; Gagarina, L.V.; Doroshina, G.Y.; Zhino, P.; Kozachek, A.V.; et al. Glaciers and Climate of Elbrus; Nestor-History Publishing House: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2020; 372p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Voloshina, A.P. Meteorology of Mountain Glaciers. Data Glaciol. Stud. 2002, 92, 3–138. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Businger, J.A.; Wyngaard, J.C.; Izumi, Y.; Bradley, E.F. Flux-Profile Relationships in the Atmospheric Surface Layer. J. Atmos. Sci. 1971, 28, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, A.L.; Lykosov, V.N. Parametrization of Atmosphere–Land Surface Interactions in Numerical Modeling of Atmospheric Processes. Proc. West Sib. Reg. Res. Inst. 1982, 55, 3–20. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Mortikov, E.V.; Debolskiy, A.V.; Glazunov, A.V.; Chechin, D.G.; Shestakova, A.A.; Suiazova, V.I.; Gladskikh, D.S. Planetary boundary layer scheme in the INMCM Earth system model. Russ. J. Numer. Anal. Math. Model. 2024, 39, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidhammer, T.; Booth, A.; Decker, S.; Li, L.; Barlage, M.; Gochis, D.; Rasmussen, R.; Melvold, K.; Nesje, A.; Sobolowski, S. Mass balance and hydrological modeling of the Hardangerjøkulen ice cap in south-central Norway. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 4275–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuffey, K.M.; Paterson, W.S.B. The Physics of Glaciers, 4th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; 704p. [Google Scholar]

- Turchaninova, A.S.; Lazarev, A.V.; Marchenko, E.S.; Seliverstov, Y.G.; Sokratov, S.A.; Petrakov, D.A.; Barandun, M.; Kenzhebaev, R.; Saks, T. Methods of snow avalanche nourishment assessment (on the example of three Tian Shan glaciers). Ice Snow 2019, 59, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenke, A.N.; Ananicheva, M.D.; Demchenko, P.F.; Kislov, A.V.; Nosenko, G.A.; Popovnin, V.V.; Khromova, T.E. Glaciers and glacial systems. In Methods for Assessing the Consequences of Climate Change for Physical and Biological Systems; Federal State Budgetary Institution “Research Center “PLANETA”: Moscow, Russia, 2012; 508p. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, A.; Mayer, C.; Hagg, W.; Popovnin, V.; Rezepkin, A.; Lomidze, N.; Svanadze, D. A comparison of glacier melt on debris-covered glaciers in the northern and southern Caucasus. Cryosphere 2011, 5, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounce, D.R.; Hock, R.; McNabb, R.W.; Millan, R.; Sommer, C.; Braun, M.H.; Malz, P.; Maussion, F.; Mouginot, J.; Seehaus, T.C.; et al. Distributed global debris thickness estimates reveal debris significantly impacts glacier mass balance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, 2020GL091311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compagno, L.; Huss, M.; Miles, E.S.; McCarthy, M.J.; Zekollari, H.; Pellicciotti, F.; Farinotti, D. Modelling supraglacial debris-cover evolution from the single glacier to the regional scale: An application to High Mountain Asia. Cryosphere 2021, 16, 1697–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovnin, V.; Gubanov, A.; Lisak, V.; Toropov, P. Recent mass balance anomalies on the Djankuat glacier, Northern Caucasus. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rets, E.P.; Popovnin, V.V.; Toropov, P.A.; Smirnov, A.M.; Tokarev, I.V.; Chizhova, J.N.; Budantseva, N.A.; Vasil’Chuk, Y.K.; Kireeva, M.B.; Ekaykin, A.A.; et al. Djankuat glacier station in the North Caucasus, Russia: A database of glaciological, hydrological, and meteorological observations and stable isotope sampling results during 2007–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1463–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rototaeva, O.V.; Nosenko, G.A.; Kerimov, A.M.; Kutuzov, S.S.; Lavrentiev, I.I.; Kerimov, A.A.; Nikitin, S.A.; Tarasova, L.N. Changes in the mass balance of the Garabashi glacier (Mt. Elbrus) at the turn of the XX-XXI centuries. Ice Snow 2019, 59, 5–22, (In Russian with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Terekhov, A.; Prokhorova, U.; Verkulich, S.; Demidov, V.; Sidorova, O.; Anisimov, M.; Romashova, K. Two decades of mass-balance observations on Aldegondabreen, Spitsbergen: Interannual variability and sensitivity to climate change. Ann. Glaciol. 2023, 64, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunakhovich, M.G.; Makarov, A.V.; Popovnin, V.V. Response of the Djankuat Glacier to Expected Climate Changes (According to the Oerlemans Model). Bulletin of Moscow University. Series 5,Geography 1996, 1, 31–37. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Verhaegen, Y.; Huybrechts, P.; Rybak, O.; Popovnin, V.V. Modelling the evolution of Djankuat Glacier, North Caucasus, from 1752 until 2100 AD. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 4039–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdov, E.D.; Toropov, P.A.; Avilov, V.K.; Artamonov, A.Y.; Polyukhov, A.A.; Zheleznova, I.V.; Yarinich, Y.I. Meteorological regime of the Elbrus high-mountain zone during the accumulation period. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2024, 60, S202–S213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernov, J.B.; Gros-Daillon, J.; Schmale, J. Comparison of selected surface level ERA5 variables against In-Situ observations in the continental Arctic. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2024, 150, 2123–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalog of Russian Glaciers. Available online: https://sites.google.com/view/glaciers-of-russia-english/main-page (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- RGI Consortium. Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI)—A Dataset of Global Glacier Outlines: Version 6.0; Technical Report; Global Land Ice Measurements from Space: Boulder, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA; METI; AIST; Japan Space Systems; U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team. ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model V003. Distributed by NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. 2018. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-astgtm-003 (accessed on 8 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Østby, T.I.; Vikhamar, T.S.; Hagen, J.O.; Hock, R.; Kohler, J.; Reijmer, C.H. Diagnosing the decline in climatic mass balance of glaciers in Svalbard over 1957–2014. Cryosphere 2017, 11, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verseghy, D.L. CLASS—The Canadian Land Surface Scheme (Version 3.6); Technical Report; Climate Research Division, Science and Technology Branch, Environment Canada: Dorval, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, R.E. A One-Dimensional Temperature Model for a Snow Cover: Technical Documentation for SNTHERM, 89; Technical Report; U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory: Hanover, NH, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorelov, A.V. Snow Cover of the Greater Caucasus: An Experience of Spatio-Temporal Analysis; Akademkniga: Moscow, Russia, 2002; 287p. [Google Scholar]

- Toropov, P.A.; Shestakova, A.A.; Smirnov, A.M.; Popovnin, V.V. Assessment of heat balance components of the Djankuat glacier (Central Caucasus) during the ablation period of 2007–2015. Earth’s Cryosphere 2018, 22, 42–54. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Toropov, P.A.; Aleshina, M.A.; Grachev, A.M. Large-scale climatic factors driving glacier recession in the Greater Caucasus, 20th–21st century. Int. J. Climatol. 2019, 39, 4703–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Vecchi, G.A.; Reichler, T. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L06805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wackera, S.; Gröbnera, J.; Vuilleumierb, L. Trends in surface radiation and cloud radiative effect over Switzerland in the past 15 years. AIP Conf. Proc. 2013, 1531, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipona, R. Greenhouse warming and solar brightening in and around the Alps. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 33, 1530–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreze, M.C.; Francis, J.A. The Arctic amplification debate. Clim. Change 2006, 76, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previdi, M.; Smith, K.L.; Polvani, L.M. Arctic amplification of climate change: A review of underlying mechanisms. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 093003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łupikasza, E.B.; Ignatiuk, D.; Grabiec, M.; Cielecka-Nowak, K.; Laska, M.; Jania, J.; Luks, B.; Uszczyk, A.; Budzik, T. The role of winter rain in the glacial system on Svalbard. Water 2019, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, S.; Miró, J.R.; Peña, J.C.; Villalba, G. Analysis of synoptic weather patterns of heatwave events. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 61, 4679–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeke, M.R. Momentum, heat and moisture budgets of katabatic wind layer over mid-latitude glacier in summer. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1997, 36, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerlemans, J.; Grisogono, B. Glacier winds and parameterisation of the related surface heat fluxes. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2002, 54, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, S.; Smith, R.; Wiltshire, A.; Payne, T.; Huss, M.; Betts, R.; Caesar, J.; Koutroulis, A.; Jones, D.; Harrison, S. Global glacier volume projections under high-end climate change scenarios. Cryosphere 2019, 13, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodin, E.M. Simulation of present-day climate with the INMCM60 model. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2023, 59, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Parameter | Parameter | Garabashi | Djankuat | Aldegonda | East Grønfjord |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphometric parameters * | General convexity of topography | Convex | Concave | Concave | Concave |

| Glacier length (m); volume (m3) | 5800; 2.8 × 108 | 3400; 1.5 × 108 | 3600; 3.9 × 108 | 5300; 3.7 × 108 | |

| Altitudinal zones, m asl | 3200/3500/3800/4100 /4400 | 2900/3200/3500 | 200/400 | 100/300 | |

| Area fraction of altitude zones | 0.05/0.15/0.4/0.25/0.15 | 0.2/0.4/0.4 | 0.7/0.3 | 0.3/0.7 | |

| Slope of altitude zones, ° | 22.5/22.5/22.5/22.5/22.5 | 16/30/10 | 5/15 | 5/5 | |

| Glacier azimuth, ° | 180 | 300 | 60 | 0 | |

| For dynamical block | 3.3 | 4 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| 0.003 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.0007 | ||

| For precipitation block | Large-scale slope in grid cell, ° | 27 | 27 | 13 | 13 |

| Maximal height in grid cell, m | 5600 | 3700 | 700 | 700 | |

| 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ||

| Parameters controlling ablation/accumulation | Temperature at the glacier bottom, °C | −8 | −4 | −4 | −4 |

| parametrization (for each zone) | On/Off/Off / Off/Off | On/On/Off | On/Off | On/Off | |

| Slope of rocks, ° | 27 | 27 | 13 | 13 | |

| Temperature of rocks, °C | 40 | 40 | 20 | 20 | |

| Debris on ice surface (for ice albedo parametrization) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fraction of thin debris on surface in the lowest zone | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Shielding effect of debris cover | Off | On | Off | Off | |

| Fraction of thick debris cover in each zone | - | 0.35/0.15/0.0 | - | - | |

| Fraction of avalanche feeding, % | 5 | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| Snow concentration coefficient in each zone | 1/1/1.1/0.9/0.8 | 2.3/2.7/3.0 | 1.5/1.8 | 1.5/1.5 |

| Glacier | Meteorological Parameters | Precipitation Rate, mm/day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P, hPa | , °C | , g kg−1 | , m s−1 | Total | Liquid | Solid | |

| Garabashi | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.08 |

| Djankuat | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.27 | −0.05 | −0.23 |

| Aldegonda | −0.14 | 0.97 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.03 |

| East Grønfjord | −0.12 | 0.98 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.05 |

| Glacier | , W m−2 | , W m−2 | A, % | , W m−2 | , W m−2 | , W m−2 | , W m−2 | H, W m−2 | LE, W m−2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garabashi | 1.98 | −1.52 | −1 | 0.89 | 1.04 | 1.59 | −0.07 | 0.60 | 0.08 |

| Djankuat | 1.50 | −1.08 | −2 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 2.35 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.03 |

| Aldegonda | −0.12 | −0.63 | −2 | 3.63 | 4.06 | 0.51 | −0.31 | 0.60 | 0.05 |

| East Grønfjord | −0.12 | −0.70 | −2 | 3.50 | 4.23 | 0.59 | −0.62 | 0.48 | −0.1 |

| Accumulation | Ablation | Mass Balance | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garabashi | Djankuat | Aldegonda | East Grønfjord | Garabashi | Djankuat | Aldegonda | East Grønfjord | Garabashi | Djankuat | Aldegonda | East Grønfjord | |

| P | −0.22 | −0.37 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.57 | −0.69 | −0.04 | −0.06 |

| −0.17 | −0.31 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.46 | 0.49 | −0.54 | −0.63 | −0.39 | −0.44 | |

| 0.21 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.38 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.67 | −0.24 | −0.36 | −0.56 | −0.62 | |

| −0.20 | −0.50 | −0.45 | −0.38 | 0.46 | −0.20 | 0.76 | 0.70 | −0.43 | −0.15 | −0.77 | −0.69 | |

| H | 0.0 | 0.30 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.34 | −0.32 | −0.09 | −0.42 | −0.31 |

| LE | −0.21 | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.21 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 0.50 | −0.14 | −0.33 | −0.55 | −0.48 |

| −0.54 | −0.54 | −0.43 | −0.32 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 0.69 | −0.92 | −0.90 | −0.71 | −0.67 | |

| 0.40 | −0.15 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.16 | −0.45 | −0.41 | −0.29 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toropov, P.A.; Shestakova, A.A.; Muraviev, A.Y.; Drozdov, E.D.; Poliukhov, A.A. The New IGRICE Model as a Tool for Studying the Mechanisms of Glacier Retreat. Climate 2025, 13, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120248

Toropov PA, Shestakova AA, Muraviev AY, Drozdov ED, Poliukhov AA. The New IGRICE Model as a Tool for Studying the Mechanisms of Glacier Retreat. Climate. 2025; 13(12):248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120248

Chicago/Turabian StyleToropov, Pavel A., Anna A. Shestakova, Anton Y. Muraviev, Evgeny D. Drozdov, and Aleksei A. Poliukhov. 2025. "The New IGRICE Model as a Tool for Studying the Mechanisms of Glacier Retreat" Climate 13, no. 12: 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120248

APA StyleToropov, P. A., Shestakova, A. A., Muraviev, A. Y., Drozdov, E. D., & Poliukhov, A. A. (2025). The New IGRICE Model as a Tool for Studying the Mechanisms of Glacier Retreat. Climate, 13(12), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120248