Enablers, Barriers and Systems for Organizational Change for Adopting and Implementing Local Governments’ Climate Mitigation Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

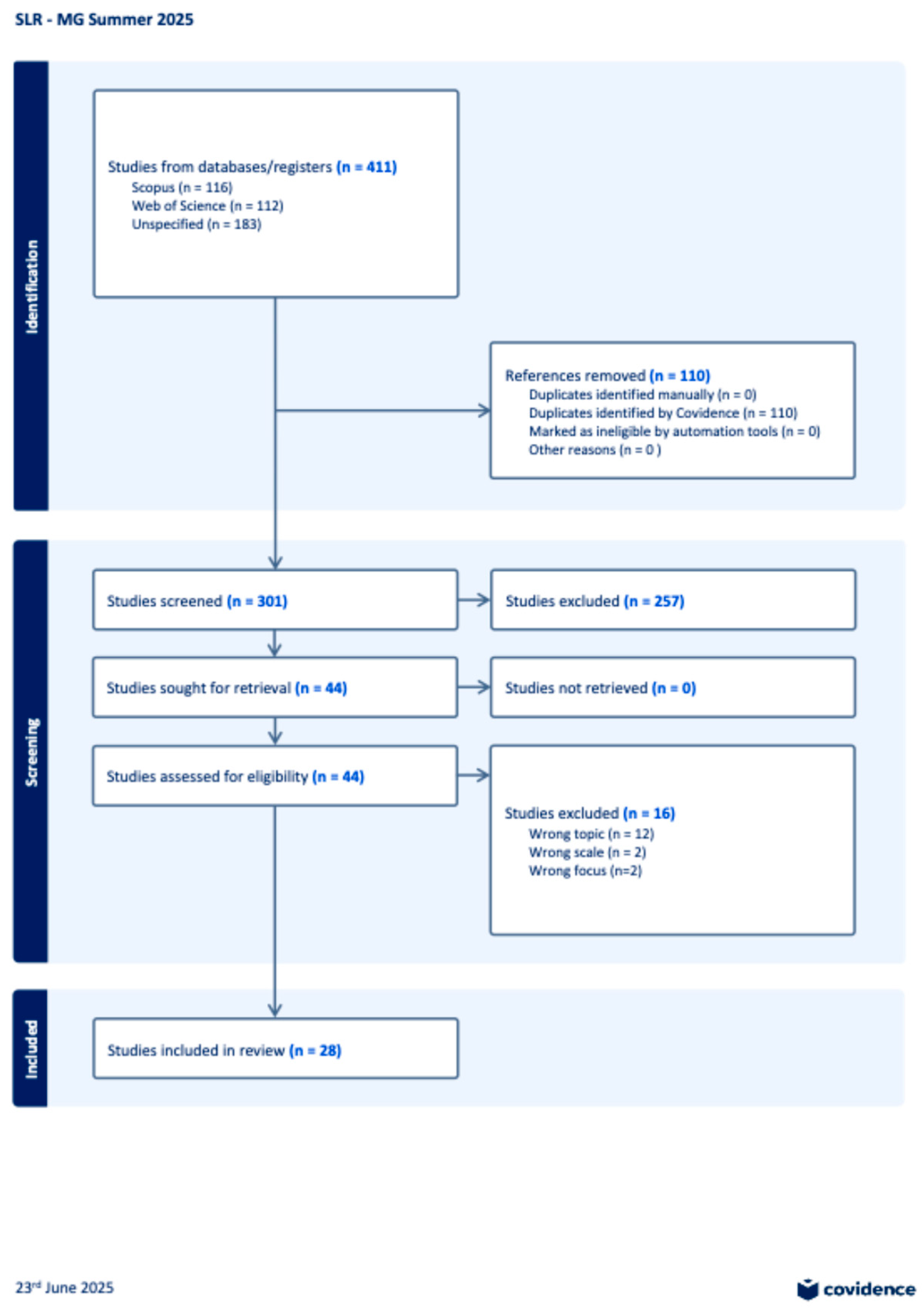

2. Research Method and Protocol

2.1. Databases

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria:

- English only

- Peer reviewed

- Scholarly Journal/Article

- Empirical data only

- 10-year Timeframe—1 January 2015–31 December 2024

- Exclusion Criteria:

- Must be local government scale (not departmental)

- Climate mitigation only (the topic)

- Must be about the organization and/or system changes (the study focus)

2.3. Keyword Search and Screening Results

2.4. Literature Coding

- What are the enablers/drivers of climate mitigation adoption in local governments?

- What are the barriers to the organizational change needed to support climate mitigation strategies?

- What are the system changes that need to be addressed to enable climate mitigation strategies?

- What are the gaps researchers are identifying in the literature?

3. Analysis and Synthesis

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Thematic Analysis

3.2.1. Enablers and Drivers to the Adoption of Climate Mitigation Strategies

Enablers Theme 1: Technology

Enablers Theme 2: Collaborative Behaviours and Actions

Enablers Theme 3: Management Culture, Structures and Leadership

Enablers Theme 4: Economics, Markets and Federal Policy

3.2.2. What Are the Barriers to the Organizational Change Needed to Support Climate Mitigation Strategies?

Barrier Theme 1: Short-Termism & Uncertainty Avoidance

Barrier Theme 2: Absence of Knowledge for Policy and Decision Making

Barrier Theme 3: Limited Resources

Barrier Theme 4: People and Organization

3.2.3. What Are the System Changes That Need to Be Addressed to Enable Climate Mitigation Strategies?

Systems Change Theme 1: Strategic Planning

Systems Change Theme 2: Innovation and Systems

Systems Change Theme 3: Resourcing

Systems Change Theme 4: Cross-Sector Collaboration and Stakeholder Engagement

4. Discussion

4.1. Transforming Local Governments for Climate Mitigation

4.2. Research Gaps Identified in the Literature

4.2.1. Deepening Our Understanding of Short-Termism and Uncertainty Avoidance

4.2.2. Leadership and Change Management in Local Government

4.2.3. Organizational Design and Behaviour in Local Governments

4.2.4. Linkages Between Corporate Sustainability and Change Management

4.2.5. Exploring Cross-Sectoral and Cross-Cutting Success in Differing Organizational Contexts

4.2.6. Sustainability Policy and Innovation Adoption

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bulkeley, H. Cities and Climate Change: Urban Sustainability and Global Environmental Governance; Routledge Studies in Physical Geography and Environment; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-203-21925-6. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, S.D.; Zahran, S.; Grover, H.; Vedlitz, A. A Spatial Analysis of Local Climate Change Policy in the United States: Risk, Stress, and Opportunity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 87, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.; Clarke, A.; Tozer, L. Strategies and Governance for Implementing Deep Decarbonization Plans at the Local Level. Sustainability 2021, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, K.E. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. In Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy; Jarret, H., Ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1966; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Gupta, J.; Qin, D.; Lade, S.J.; Abrams, J.F.; Andersen, L.S.; Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Bai, X.; Bala, G.; Bunn, S.E.; et al. Safe and Just Earth System Boundaries. Nature 2023, 619, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.W.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; Blanco, G.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Forino, G.; von Meding, J.; Brewer, G.; van Niekerk, D. Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction Integration: Strategies, Policies, and Plans in Three Australian Local Governments. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 24, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, F.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Homer-Dixon, T.; Vredenburg, H.; Loorbach, D.; Thompson, J.; Nilsson, M.; Lambin, E.; Sendzimir, J.; et al. Tipping toward Sustainability: Emerging Pathways of Transformation. Ambio 2011, 40, 762–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H. Ecological Resilience in Theory and Application. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Liu, G.; Xu, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, C. University Campus Based Zero-Carbon Action Plans for Accelerating the Zero-Carbon City Transition. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, C.; Herman, R. Green Cities—A Key Element of the Sustainable Economy. Manager 2021, 34, 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pasimeni, M.; Valente, D.; Zurlini, G.; Petrosillo, I. The Interplay between Urban Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies to Face Climate Change in Two European Countries. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 95, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cities, Climate Change and Multilevel Governance. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/cities-climate-change-and-multilevel-governance_220062444715.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Kern, K.; Alber, G. Governing Climate Change in Cities: Modes of Urban Climate Governance in Multi-Level Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Competitive Cities and Climate Change, Milan, Italy, 9–10 October 2009; OECD: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, S.D.; Zahran, S.; Grover, H.; Vedlitz, A. Risk, Stress, and Capacity: Explaining Metropolitan Commitment to Climate Protection. Urban Aff. Rev. 2008, 43, 447–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.; Mitchell, C.L. The Role of Boundary Organizations in Climate Change Adaptation from the Perspective of Municipal Practitioners. Clim. Chang. 2016, 139, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Calcagno, R.; Magarelli, S.M.; Saliba, M. A Relationship between Corporate Sustainability and Organizational Change (Part One). Ind. Commer. Train. 2016, 48, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, R.; Peters, B.G.; Tosun, J. Public Bureaucracy and Climate Change Adaptation. Rev. Policy Res. 2018, 35, 776–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S.R.; Hardy, C. Studying Organization: Theory and Method; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-85702-211-0. [Google Scholar]

- Osthorst, W. Tensions in Urban Transitions. Conceptualizing Conflicts in Local Climate Policy Arrangements. Sustainability 2021, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, S. Transforming Barriers into Enablers of Action on Climate Change: Insights from Three Municipal Case Studies in British Columbia, Canada. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristianssen, A.C.; Granberg, M. Transforming Local Climate Adaptation Organization: Barriers and Progress in 13 Swedish Municipalities. Climate 2021, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, C.; Clarke, A. Leadership and Climate Change Mitigation: A Systematic Literature Review. Climate 2024, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylett, A. The Socio-Institutional Dynamics of Urban Climate Governance: A Comparative Analysis of Innovation and Change in Durban (KZN, South Africa) and Portland (OR, USA). Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1386–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Christofi, M. R&D Internationalization and Innovation: A Systematic Review, Integrative Framework and Future Research Directions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmatier, R.W.; Houston, M.B.; Hulland, J. Review Articles: Purpose, Process, and Structure. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scopus|Abstract and Citation Database|Elsevier. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Web of Science Platform|Clarivate. Available online: https://clarivate.com/academia-government/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-referencing/web-of-science/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Academic. Available online: https://about.proquest.com/en/libraries/academic/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Covidence—Better Systematic Review Management. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinski, N.; Pinkse, J.; Busch, T.; Banerjee, S.B. The Role of Short-Termism and Uncertainty Avoidance in Organizational Inaction on Climate Change. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 253–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Wolf, F.; Moncada, S.; Lange, S.A.; Babatunde, B.A.; Skanavis, C.; Kounani, A.; Nunn, P.D. Transformative Adaptation as a Sustainable Response to Climate Change: Insights from Large-Scale Case Studies. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2022, 27, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Livramento Gonçalves, G.; Filho, W.L.; da Silva Neiva, S.; Deggau, A.B.; de Oliveira Veras, M.; Ceci, F.; de Lima, M.A.; de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O. The Impacts of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on Smart and Sustainable Cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, R. Continuity and Adaptability: A Collaborative, Eco-Industrial Park (EIP)-Focused Approach to Managing Small Town Community (STC) Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2017, 12, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.W.; Green, J.F.; Keohane, R.O. Organizational Ecology and Institutional Change in Global Governance. Int. Organ. 2016, 70, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borry, E.L. Ethical Climate and Rule Bending: How Organzational Norms Contribute to Unintended Rule Consequences. Public Adm. 2017, 95, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y. Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Fiscal Policy and Corporate Green Technology Innovation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1056038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aedi, N. Strategies and Best Practices for Implementing Green Campus: A Change Management Reviews. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkandawire, B.; Thole, B.; Mamiwa, D.; Mlowa, T.; McClure, A.; Kavonic, J.; Jack, C. Application of Systems-Approach in Modelling Complex City-Scale Transdisciplinary Knowledge Co-Production Process and Learning Patterns for Climate Resilience. Systems 2021, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, E. Sustainable Development and Urban Planning Regulations in the Context of Climate Change Management Measures. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilssen, M.; Hanssen, G.S. Institutional Innovation for More Involving Urban Transformations: Comparing Danish and Dutch Experiences. Cities 2022, 131, 103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikandar, S.M.; Ali, S.M.; Hassan, Z. Harmonizing Smart City Tech and Anthropocentrism for Climate Resilience and Nature’s Benefit. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country of Research | # of Articles—n = |

|---|---|

| USA | 6 |

| Multiple Country Study | 6 |

| Brazil | 1 |

| Canada | 1 |

| China | 1 |

| Lithuania | 1 |

| South Korea | 1 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| UK | 1 |

| Continent of Research | |

| Africa | 5 |

| Australia | 2 |

| Europe | 2 |

| Total | 28 |

| Research Method | # of Articles—n = |

|---|---|

| Qualitative | 14 |

| Quantitative | 1 |

| Mixed Method Design | 7 |

| Conceptual | 4 |

| Other | 2 |

| Total | 28 |

| Journals | # of Articles—n = |

|---|---|

| Sustainability | 3 |

| Climatic Change | 2 |

| Administrative Sciences | 1 |

| Business and Society | 1 |

| Climate | 1 |

| Cities | 1 |

| Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues | 1 |

| Environmental Science and Policy | 1 |

| Frontiers in Psychology | 1 |

| Global Ecology and Conservation | 1 |

| Industrial and Commercial Training | 1 |

| Implementation Science | 1 |

| International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management | 1 |

| International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning | 1 |

| International Organization | 1 |

| Journal of Ecohumanism | 1 |

| Manager | 1 |

| Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change | 1 |

| Nature Communications | 1 |

| Public Administration | 1 |

| Public Personnel Management | 1 |

| Scientific Reports | 1 |

| Social Sciences and Humanities Open | 1 |

| Systems | 1 |

| Urban Policy and Research | 1 |

| Total | 28 |

| Enabler Theme | Barrier Theme | Systems Theme | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Technology | Short-termism and Uncertainty Avoidance | Strategic Planning |

| 2 | Collaborative Behaviors and Actions | Absence of Knowledge for Policy and Decision making | Innovations and Systems |

| 3 | Management Cultures, structures, and Leadership | Limited Resources | Resourcing |

| 4 | Economics, Markets and Federal Policy | People and Culture | Cross-sector Collaboration and Stakeholder Engagement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goudsblom, M.; Clarke, A. Enablers, Barriers and Systems for Organizational Change for Adopting and Implementing Local Governments’ Climate Mitigation Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Climate 2025, 13, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13110228

Goudsblom M, Clarke A. Enablers, Barriers and Systems for Organizational Change for Adopting and Implementing Local Governments’ Climate Mitigation Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Climate. 2025; 13(11):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13110228

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoudsblom, Mark, and Amelia Clarke. 2025. "Enablers, Barriers and Systems for Organizational Change for Adopting and Implementing Local Governments’ Climate Mitigation Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review" Climate 13, no. 11: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13110228

APA StyleGoudsblom, M., & Clarke, A. (2025). Enablers, Barriers and Systems for Organizational Change for Adopting and Implementing Local Governments’ Climate Mitigation Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Climate, 13(11), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13110228