Diurnal Extrema Timing—A New Climatological Parameter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

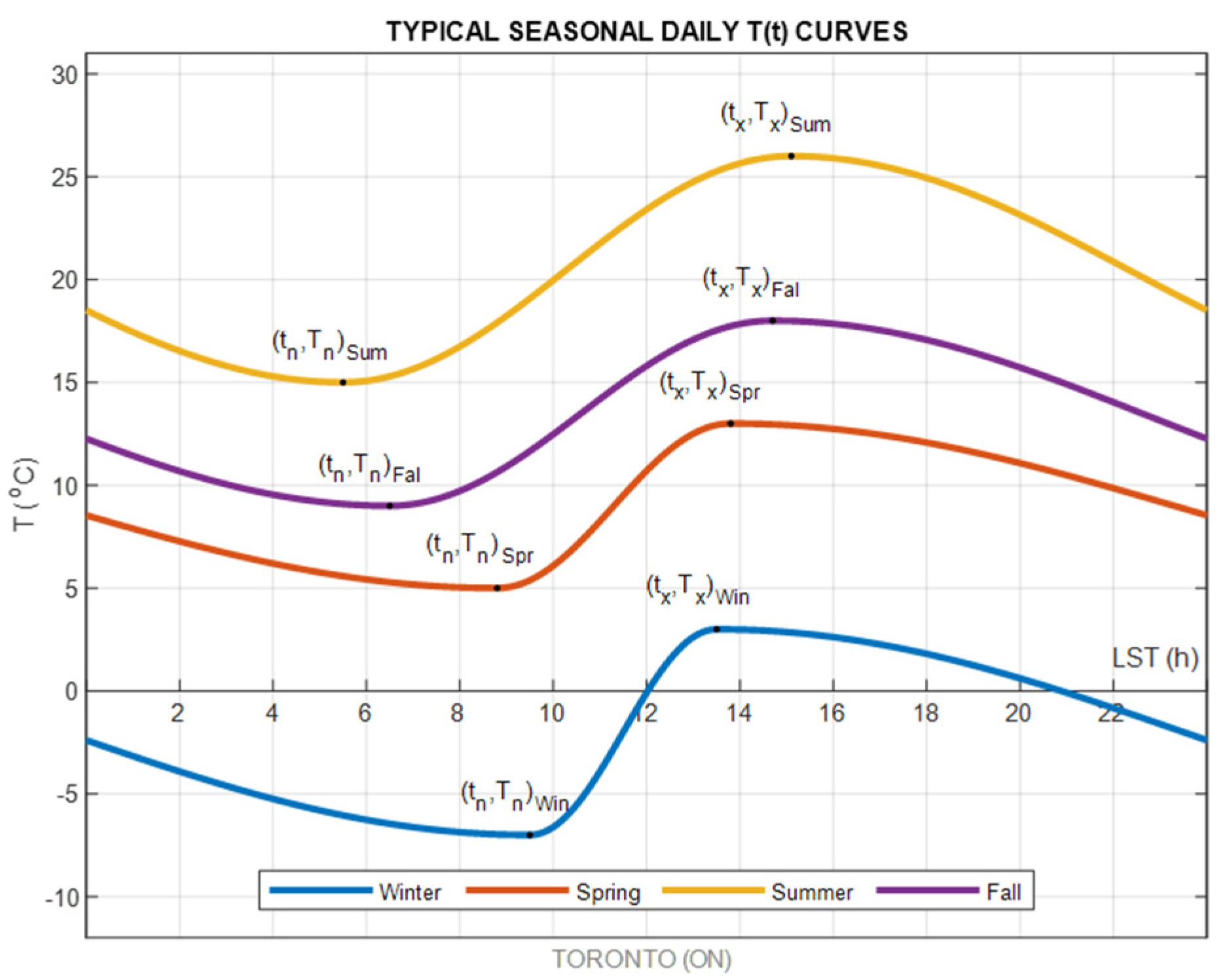

1.1. Definition of Air Temperature Extrema

1.2. Diurnal Extrema Timing

1.3. Canadian Temperature Extrema Bias

1.4. Calendar Day vs. Climatological Day for Extrema Observations

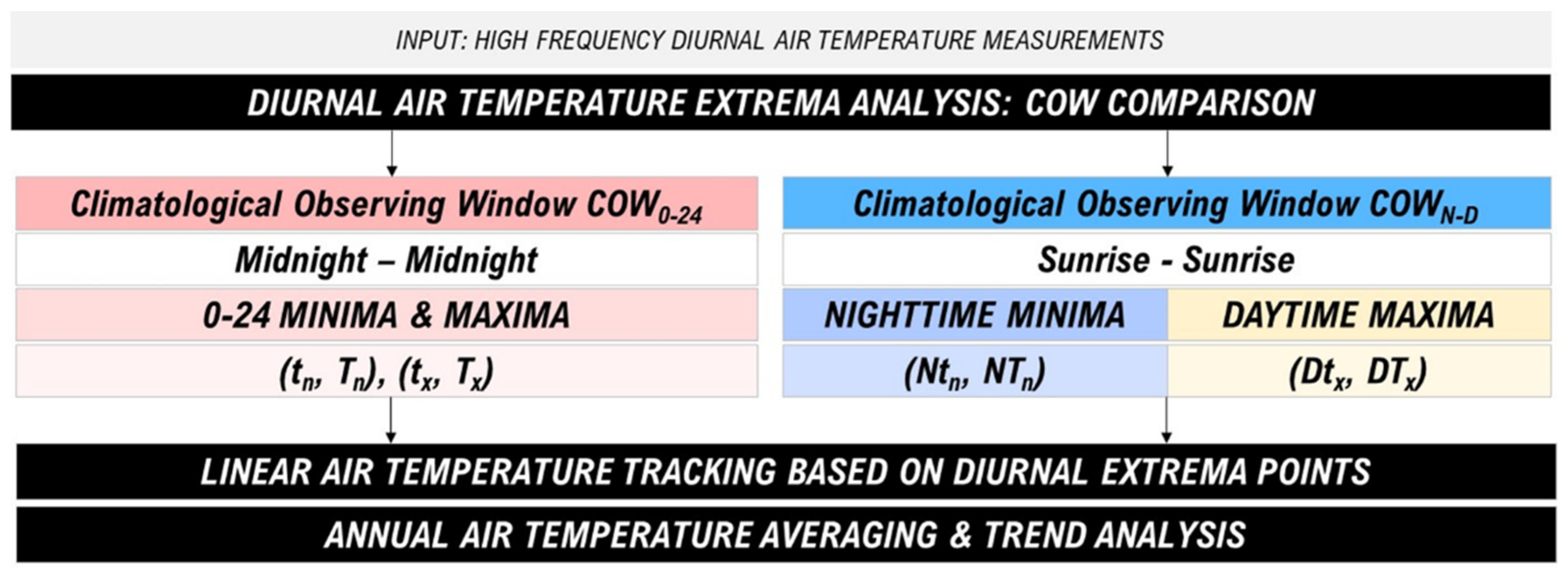

1.5. Climatological Observing Window

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Air Temperature Data and Analysis

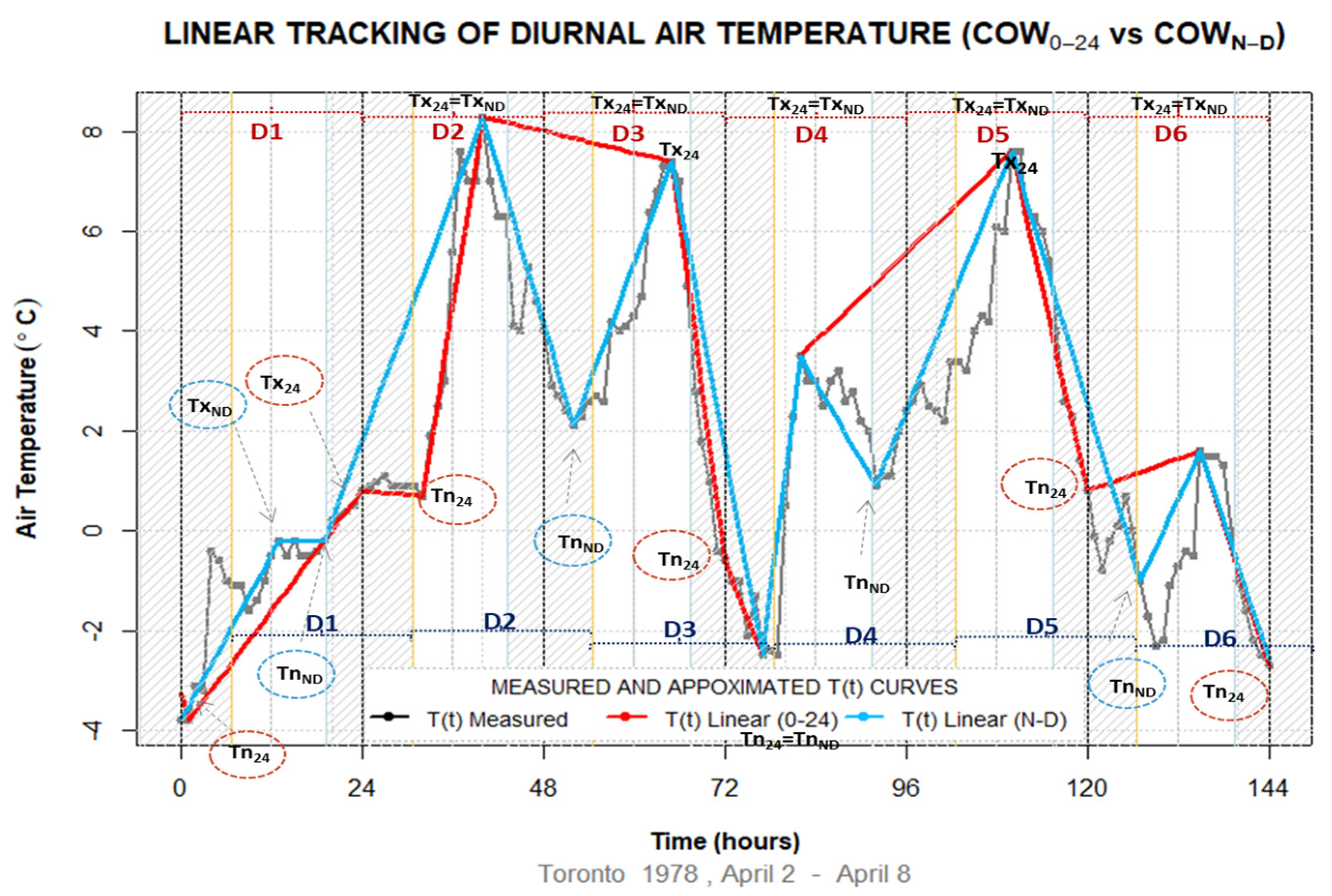

- Daily minimum and maximum and their timing are identified using COW0–24 and COWN–D methods to obtain a series of daily extrema. A common point between the methods is that both use MIN/MAX functions to find the lowest/largest number on a preselected time interval. The key difference between the methods is the specification of the search interval. While the COW0–24 extrema identification method identifies the lowest and largest value within the 24-h interval starting at midnight, the COWN–D method divides 24 h into a daytime and nighttime interval starting at sunrise and sunset, respectively. The COWN–D approach uses the advantage of prior knowledge or expectation that true mathematical extrema occur during separate nighttime and daytime periods. The extrema further serve as connection points for artificial temperature generation used in the testing of conformity of air temperature tracking with hourly temperature observations.

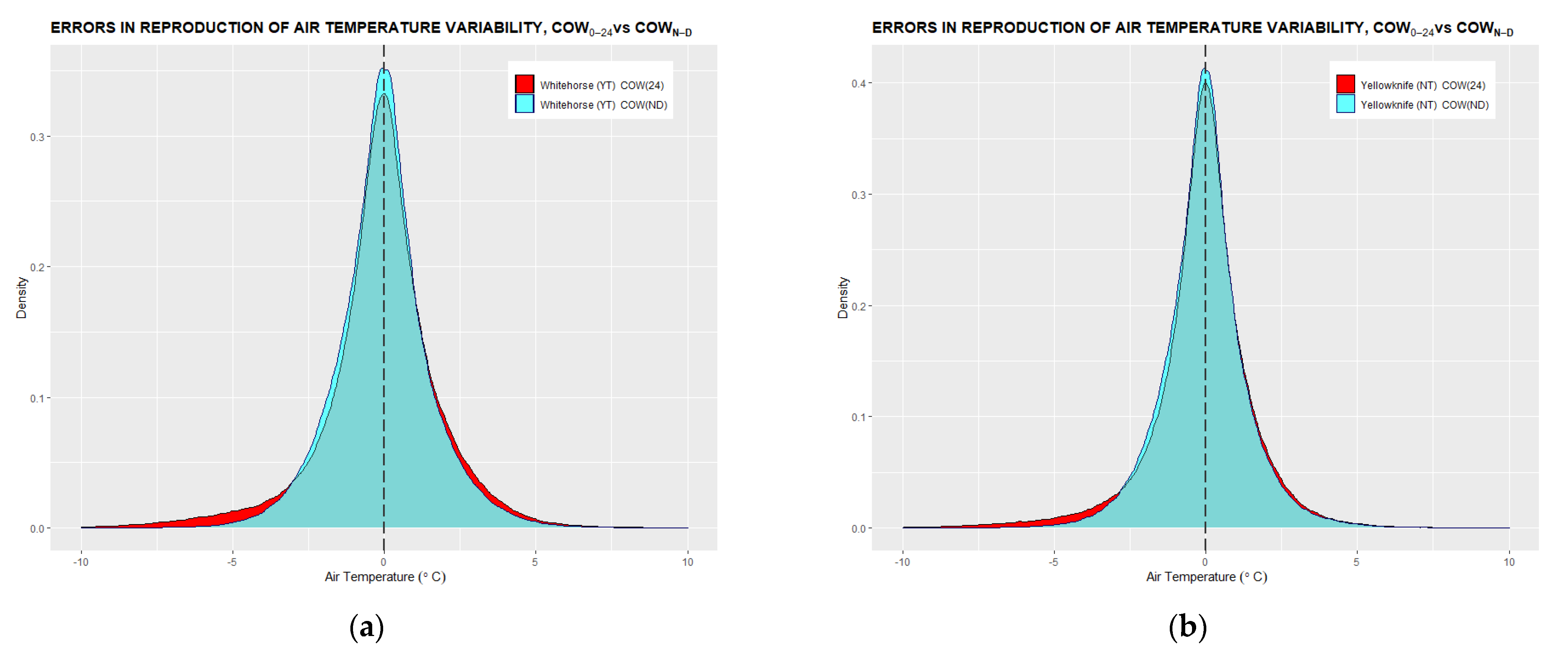

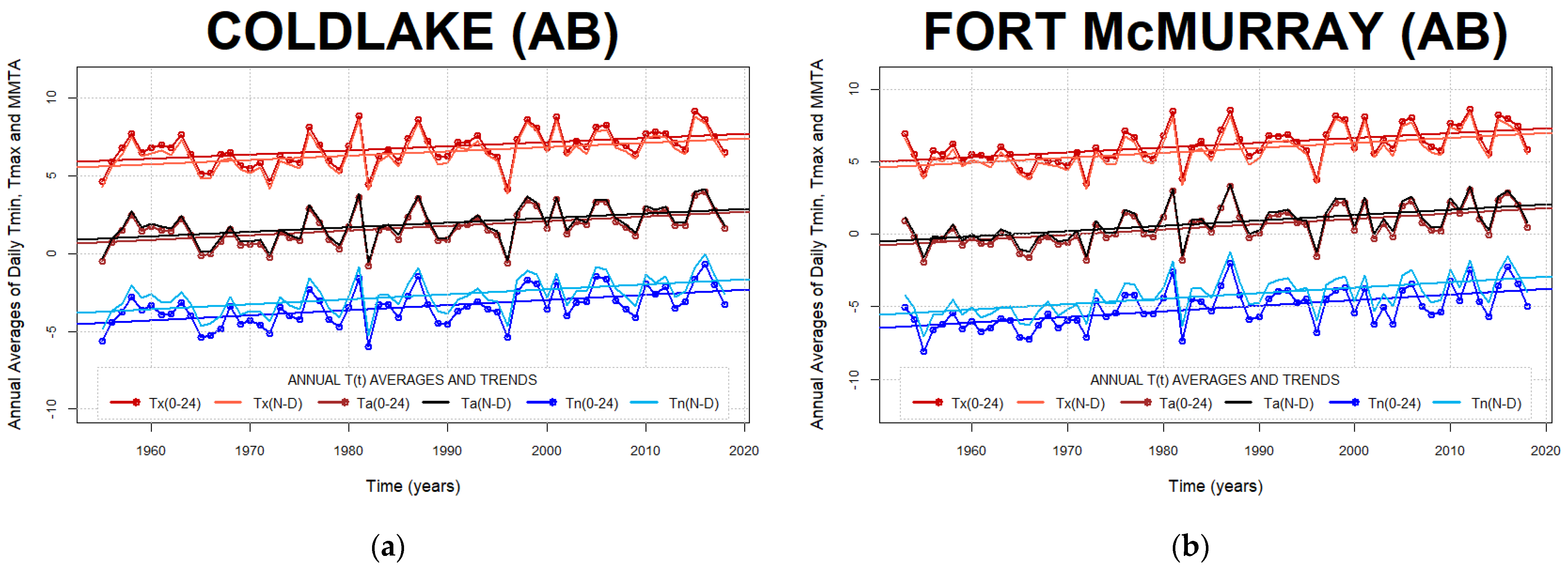

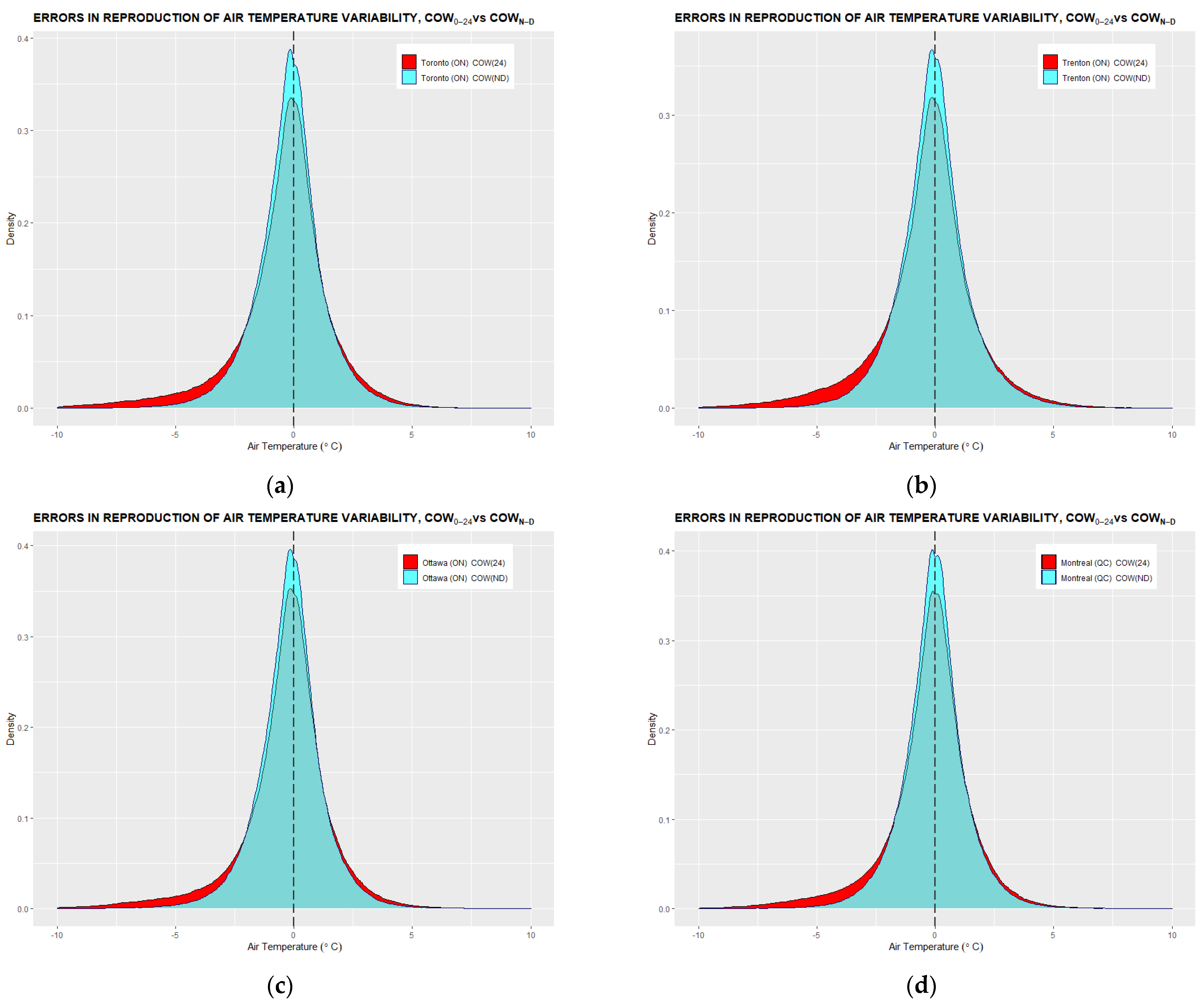

- Air temperature tracking connects consecutive extrema into a continuous approximation of temperature variability used for the calculation of hourly differences between measured and calculated temperatures. The accuracy of each hourly point generated by COW0–24 and COWN–D methods is verified against the measured temperature for comparing the performance of COW methods in the identification of mathematical extrema. The error distributions in air temperature tracking are then contrasted for benchmarking and identification of systematic biases. Due to the higher accuracy of the COWN–D search method in temperature tracking, the COWN–D chronologically ordered sequence of daily temperature extrema is used further as a close representation of true temperature variability.

- The daily mean of extrema, i.e., the Min-Max Average (MMA), and the difference between daily maximum and minimum, i.e., Diurnal Temperature Range (DTR) are determined for calculation of discrepancies between the COW0–24 and COWN–D extrema identification methods.

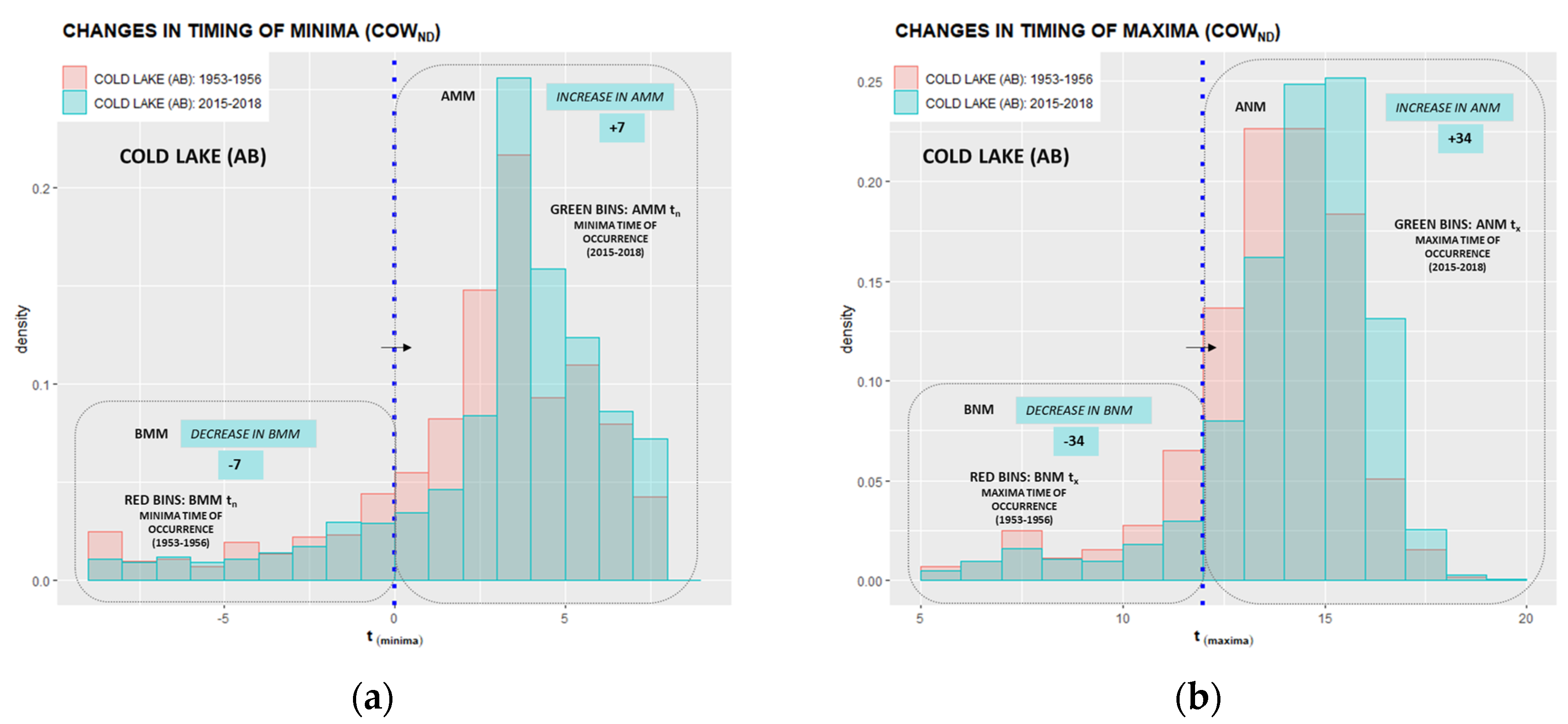

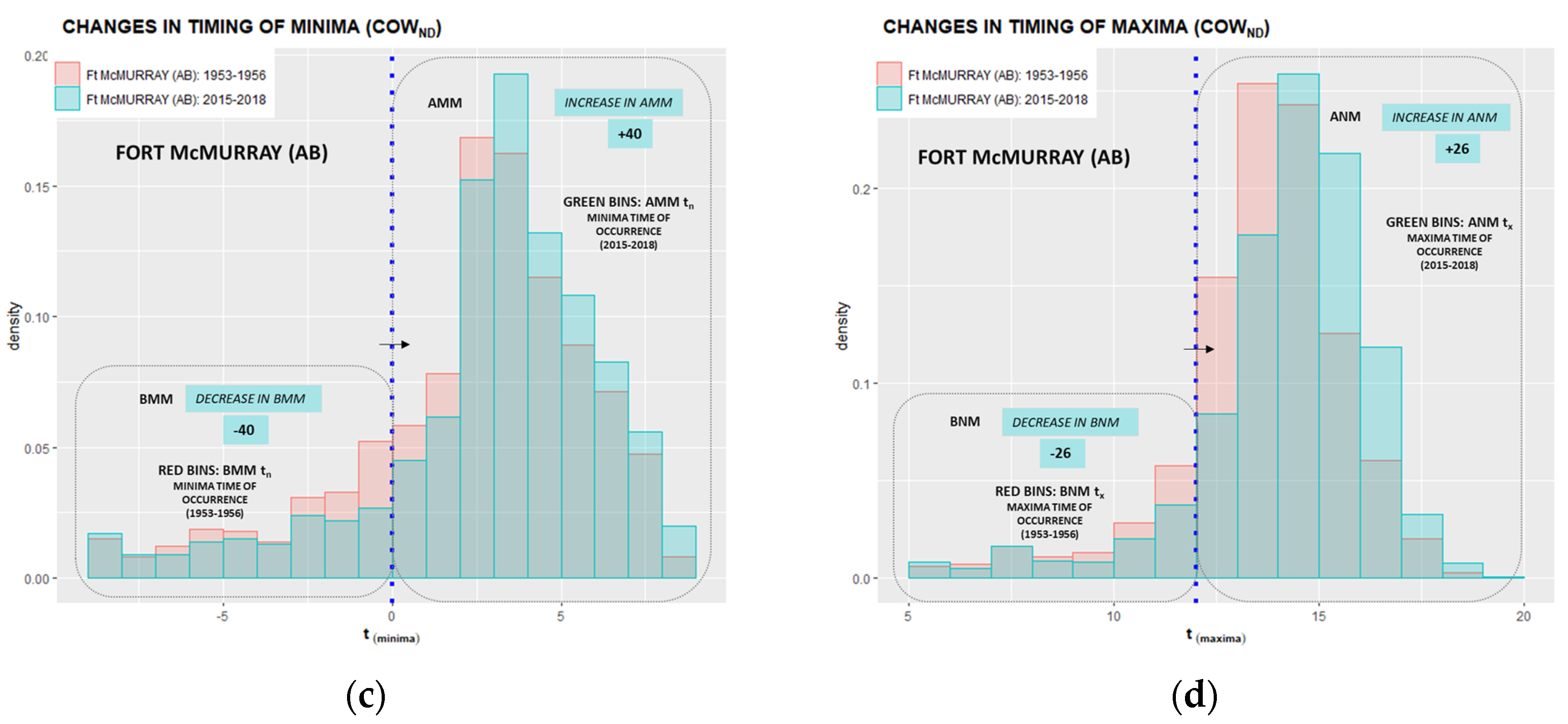

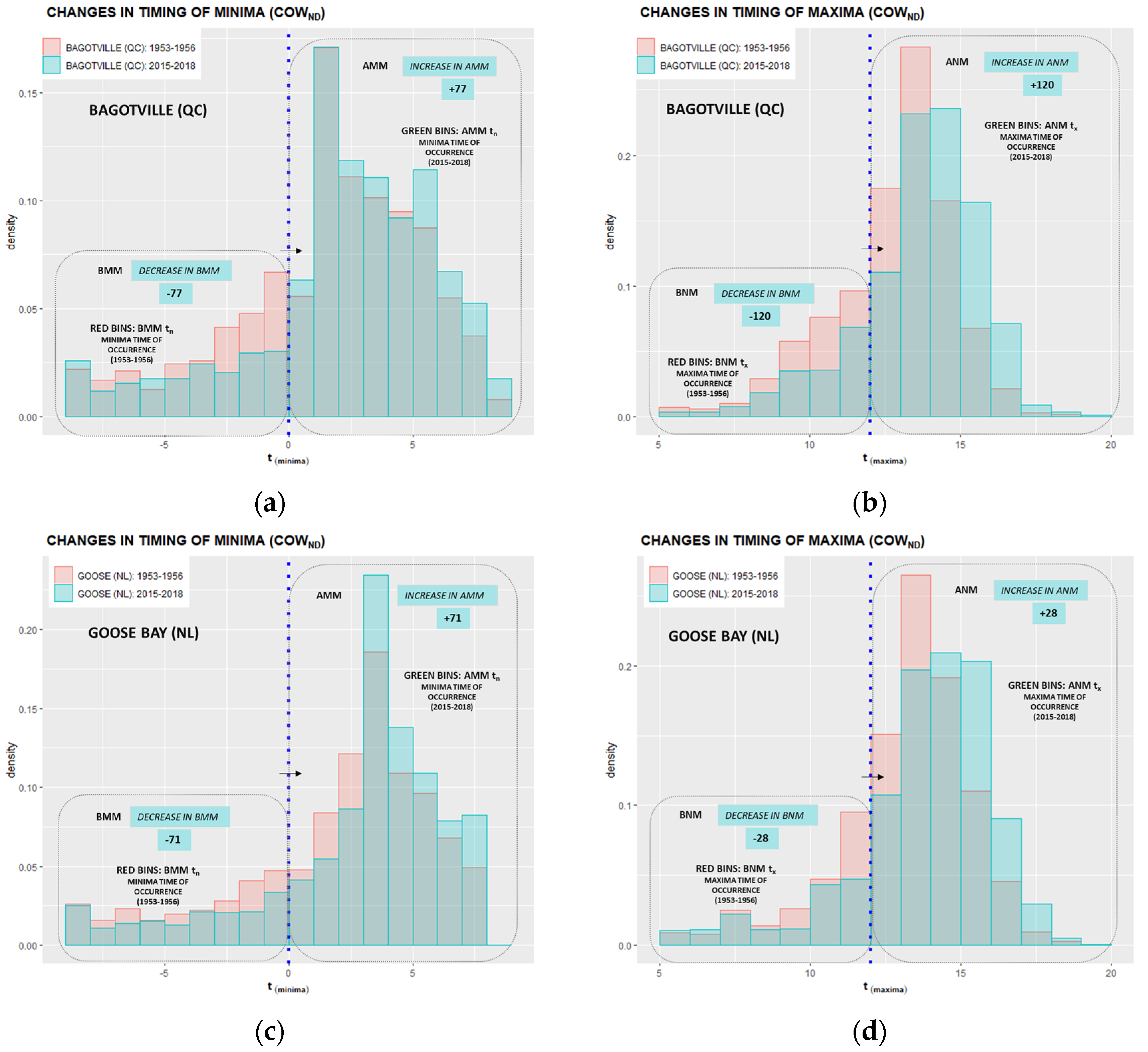

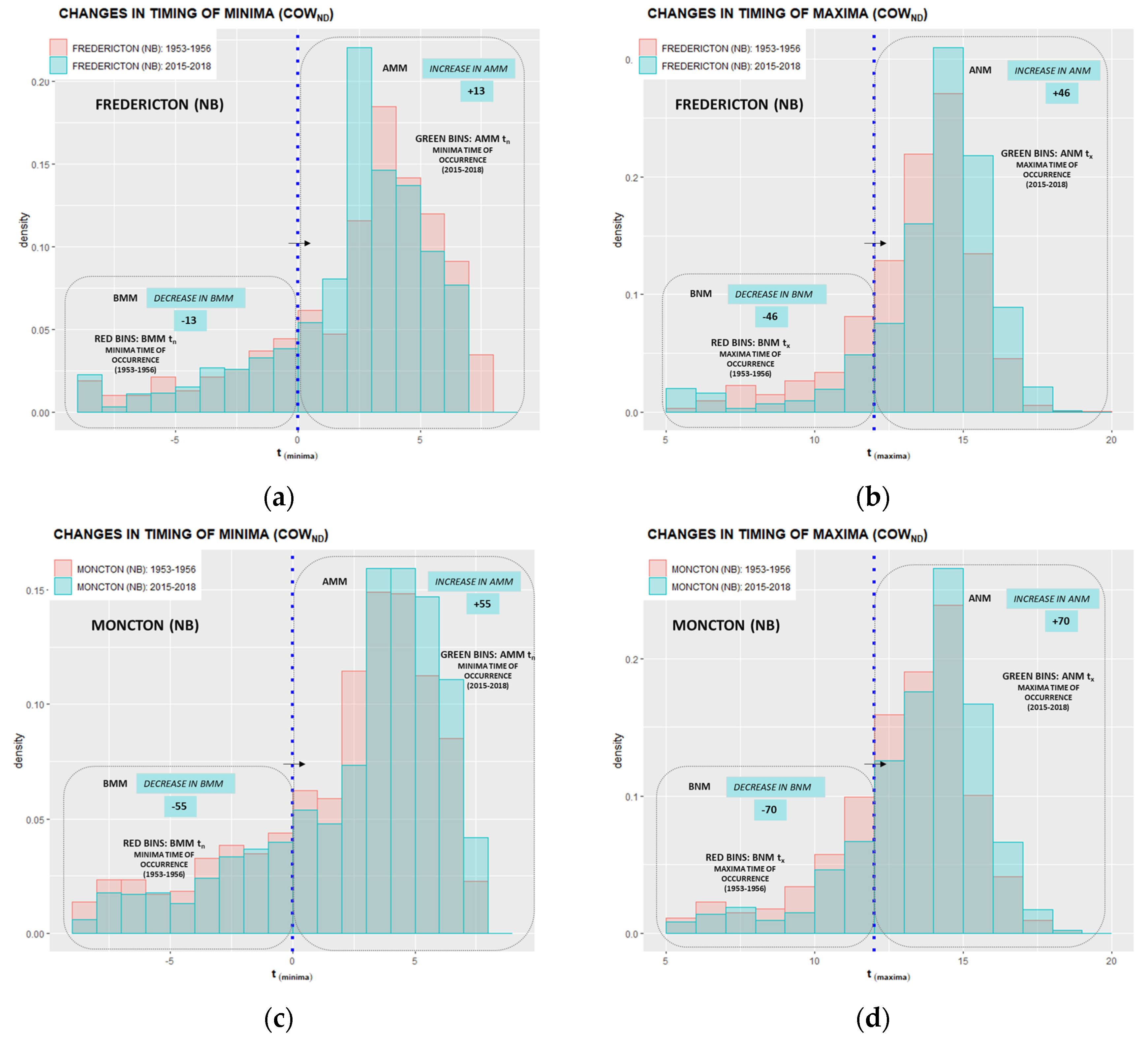

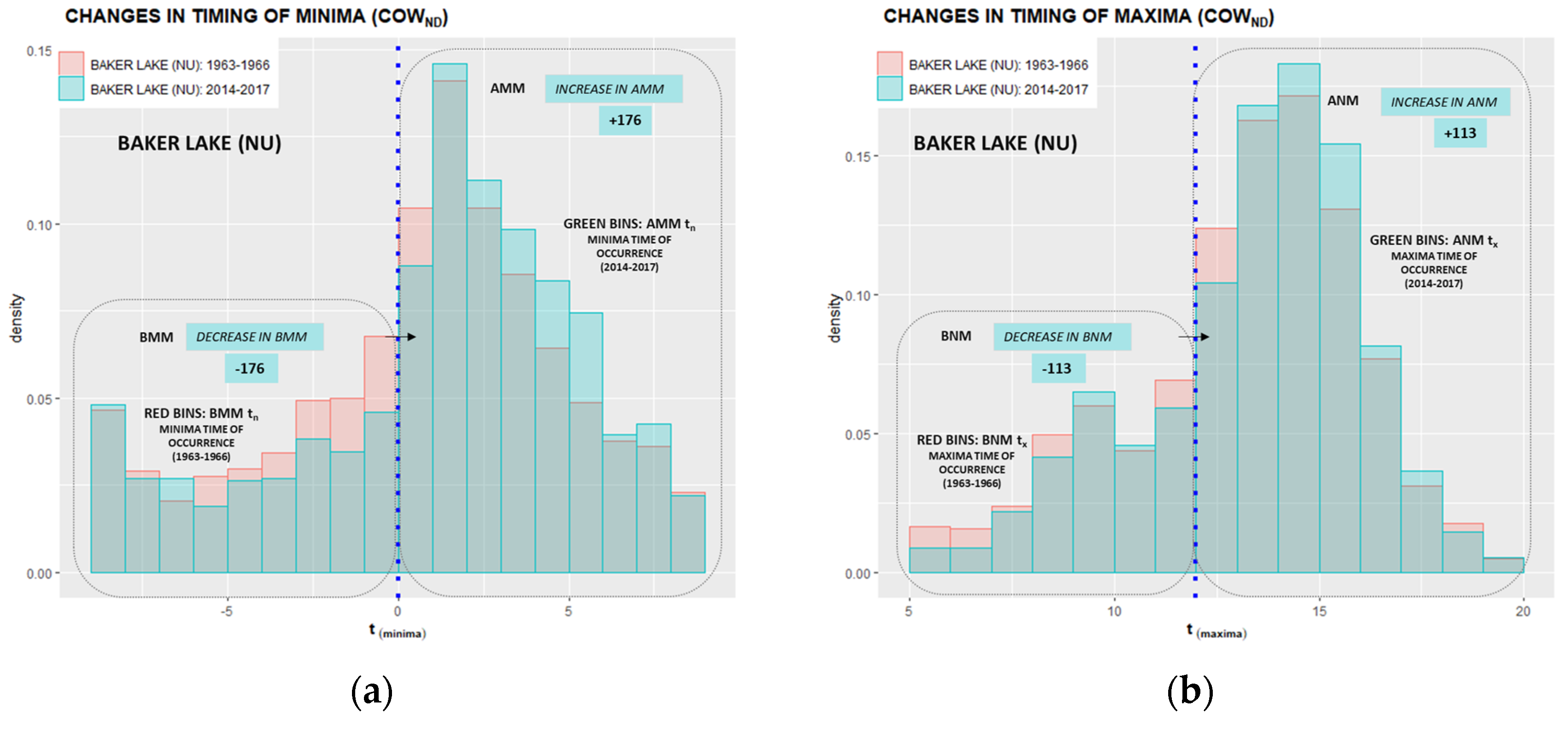

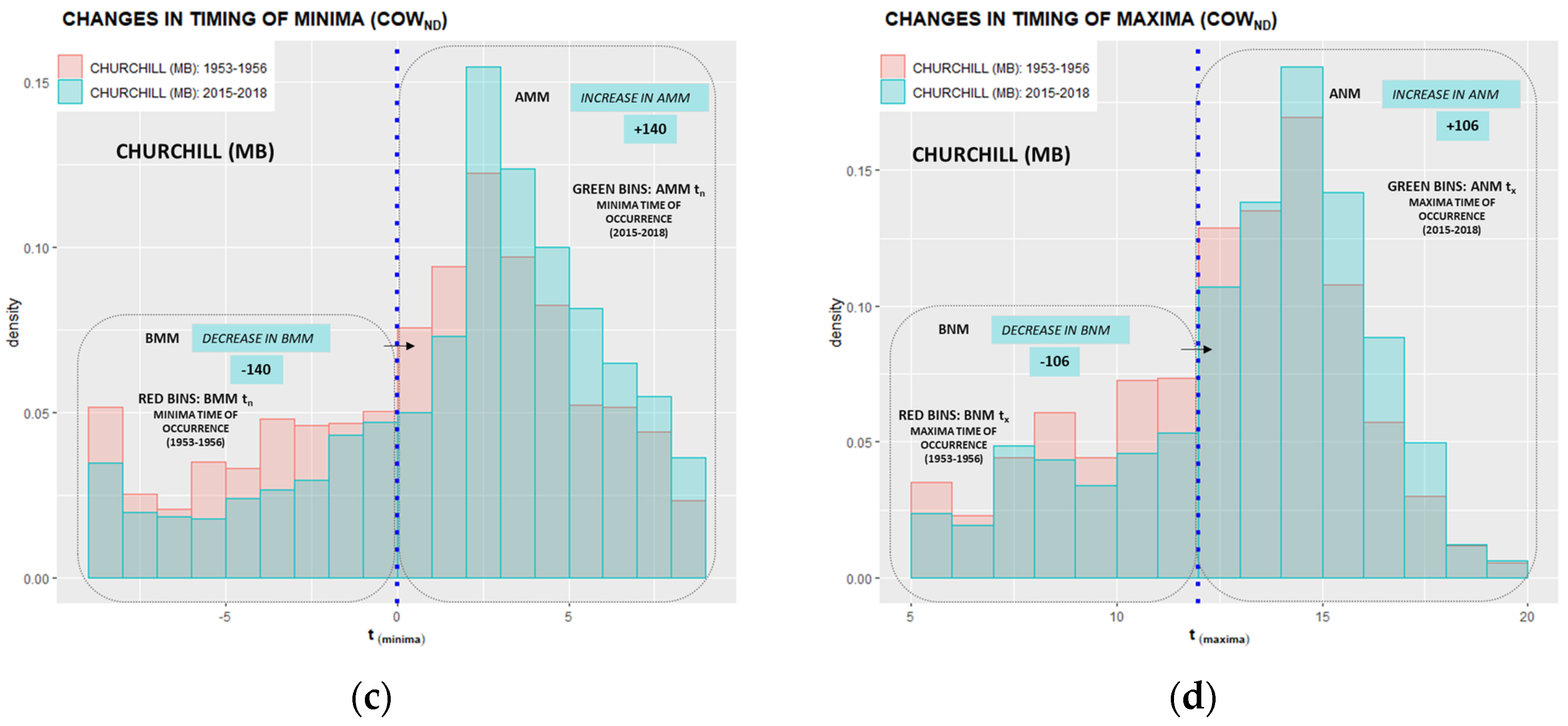

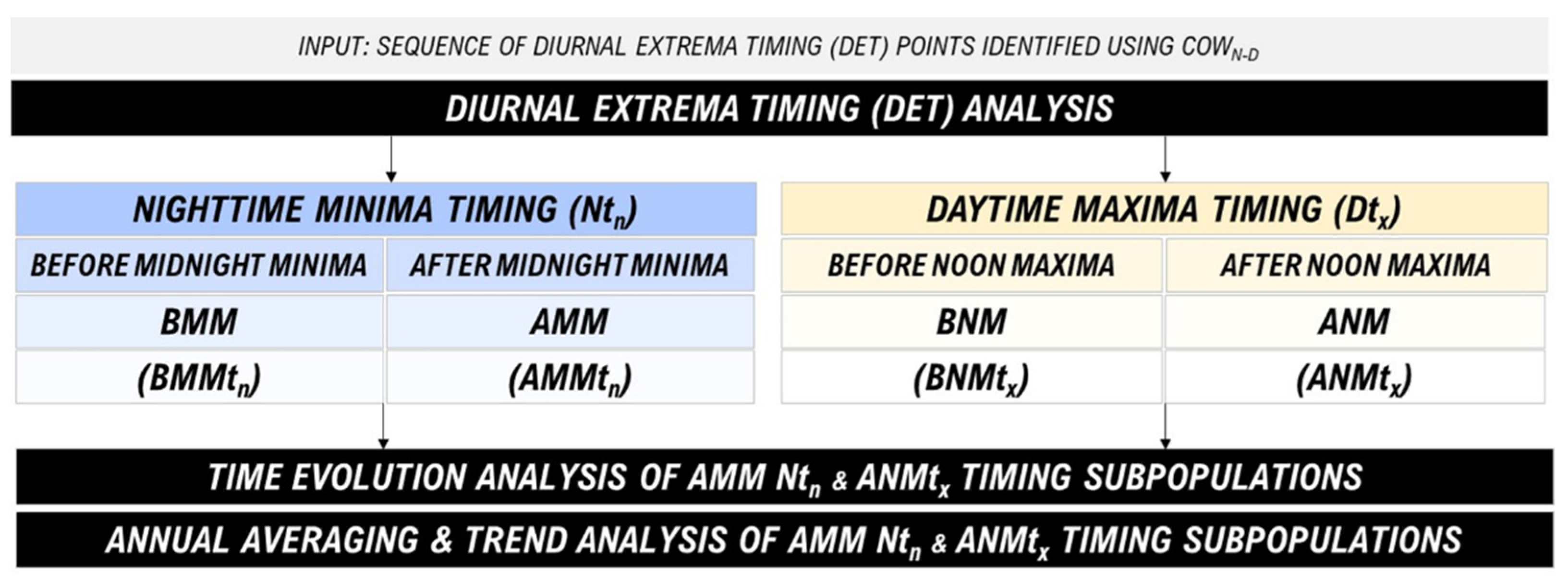

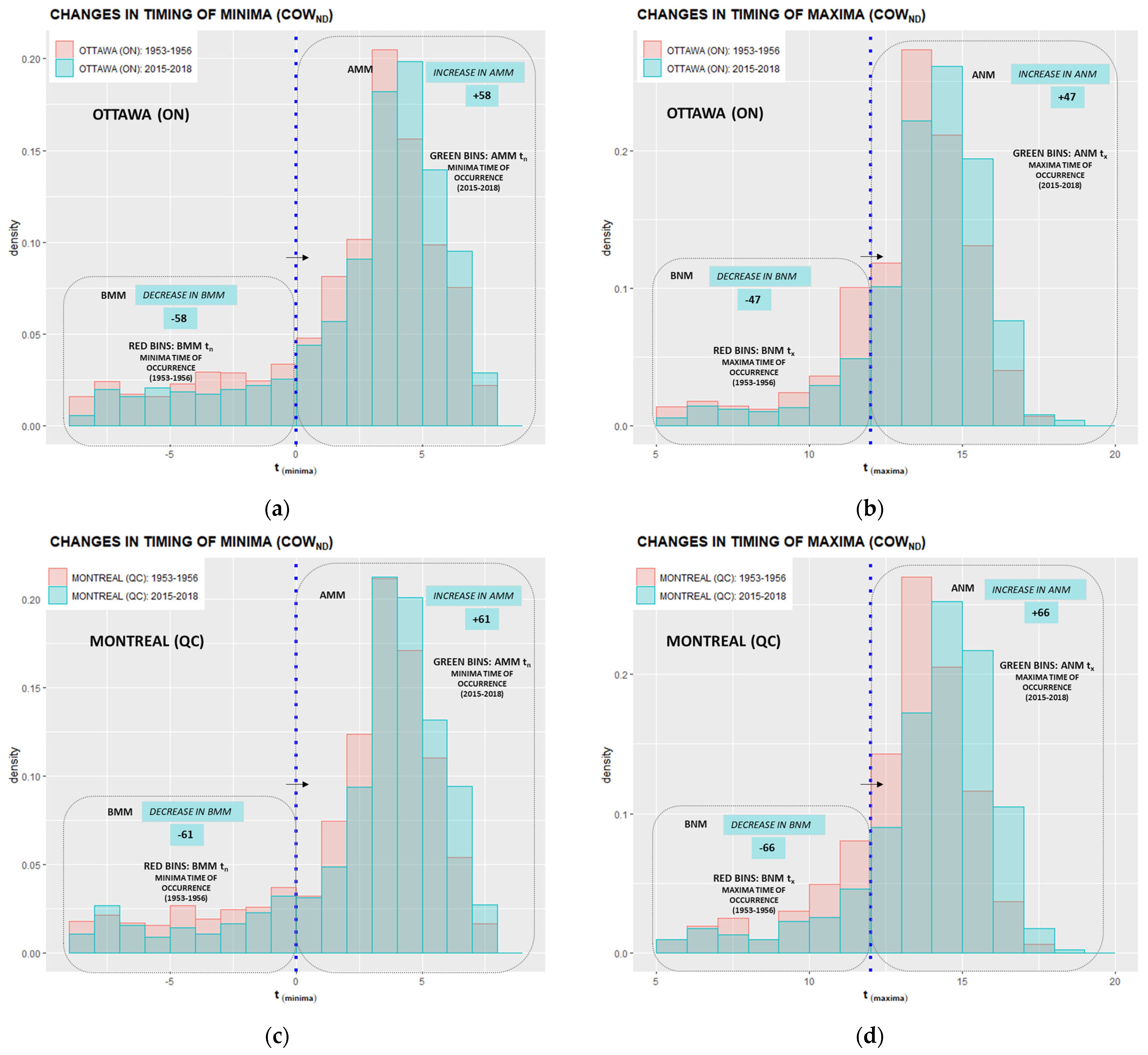

- Nighttime and daytime populations of minima and maxima temperature-time pairs are further divided into “before” and “after” subpopulations for the examination of counts and their “migration” across midnight and noon delineations. The migration of DET counts refers to a displacement of “before” timing members to the “after” subpopulations effectively causing shifts in minima and maxima timing.

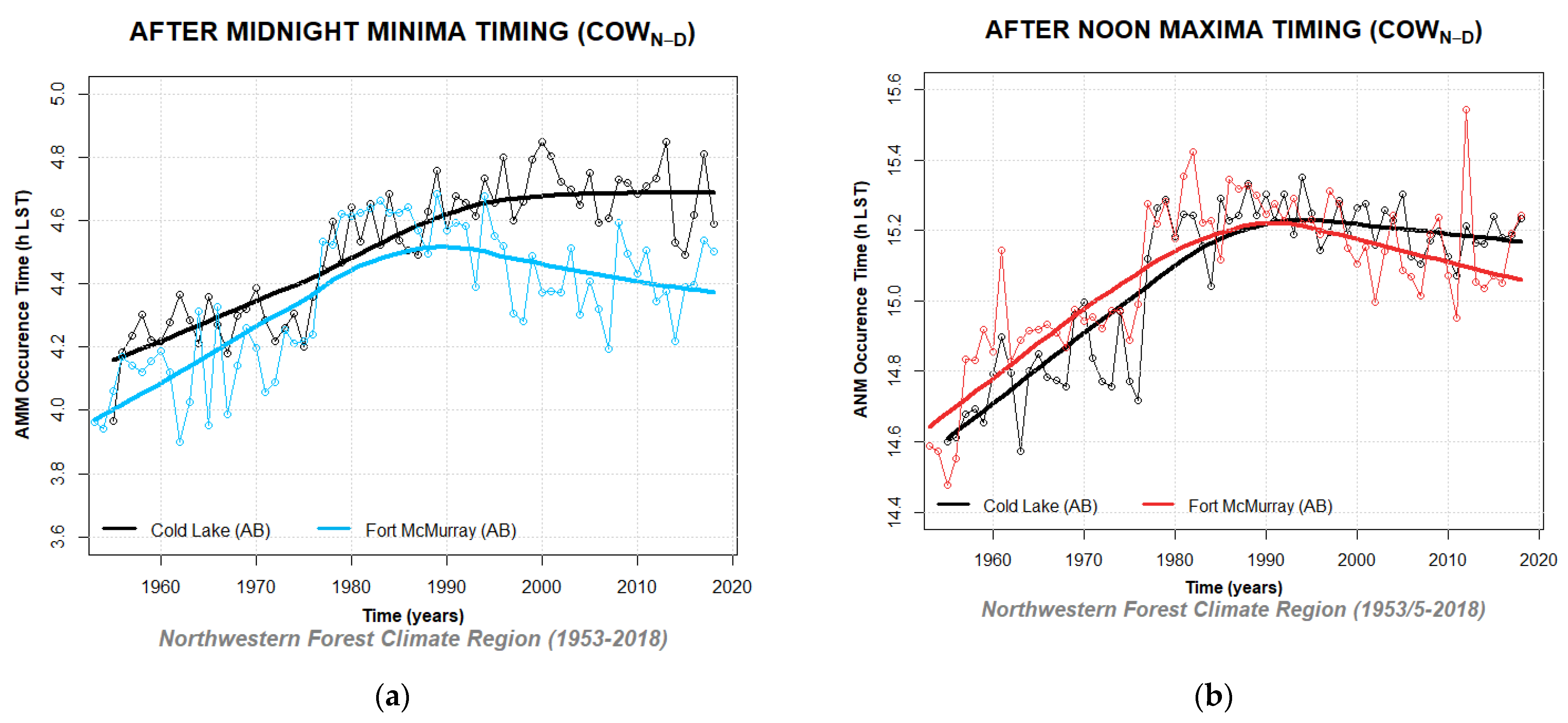

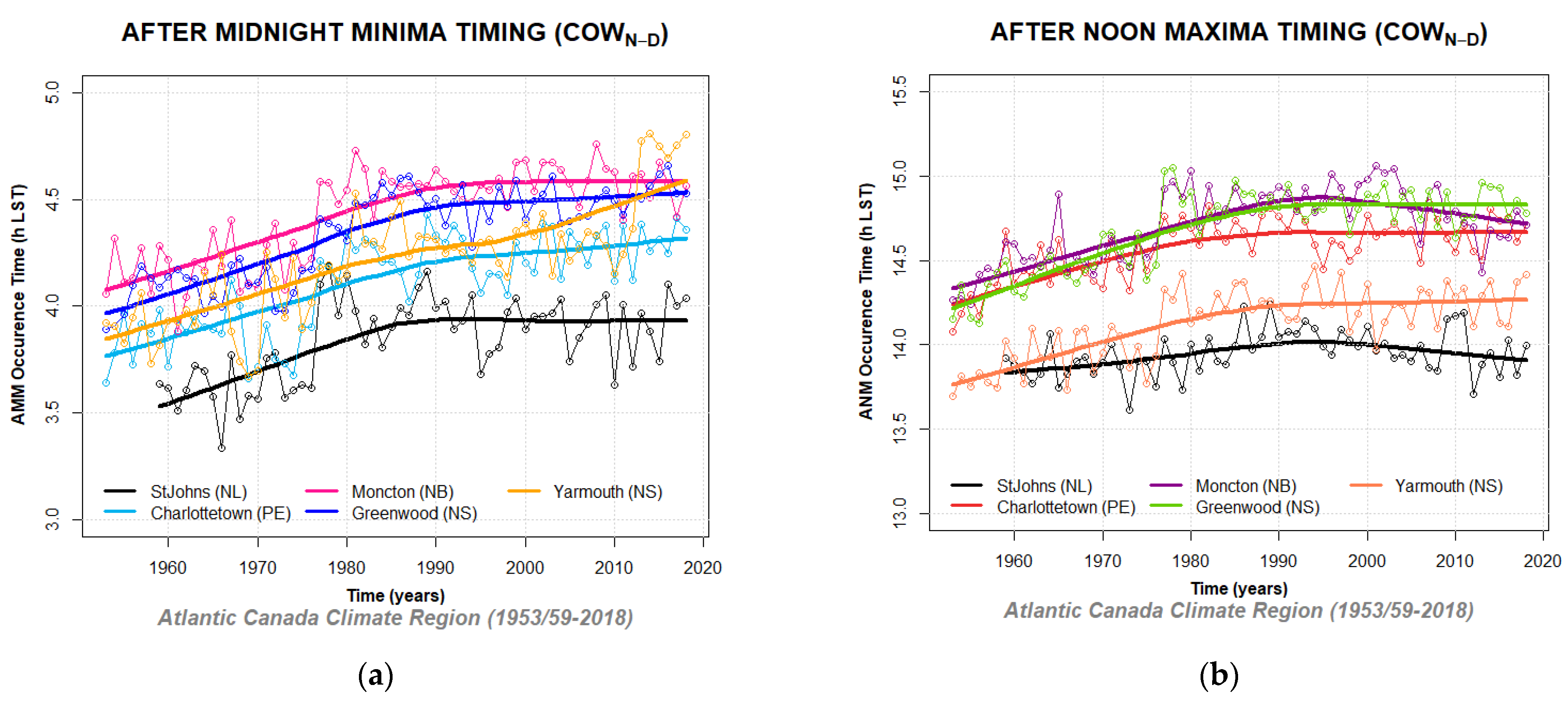

- The timing subpopulations are subjected to analysis of time trends and shifts in historical temperature-time series. Time trends of timing subpopulations are analyzed using the Mann–Kendal (MK) trend test in the R code.

- The sensitivity of diurnal temperature and timing parameters to climate change is evaluated afterward with the newly introduced Climate Parameter Sensitivity Index that examines the change of temperature and timing indices relative to their range of variability.

2.2. Identification of Diurnal Temperature-Time Extrema Pairs

2.3. Linear Temperature Tracking

- a.

- Consecutive daily extrema are linearly connected and air temperatures for hours in between the extrema are calculated. This step yields two artificial or recreated sets of hourly temperatures based on COW0–24 and COWN–D extrema.

- b.

- The calculated hourly temperatures are compared to the corresponding measured hourly temperatures to form two sets of hourly differences or errors associated with COW0–24 and COWN–D extrema identification methods.

- c.

- Two sets of error distributions in linear tracking are then statistically assessed and compared against each other for accuracy benchmarking. The benchmarking criteria are symmetry, mean, and standard deviation of the distribution.

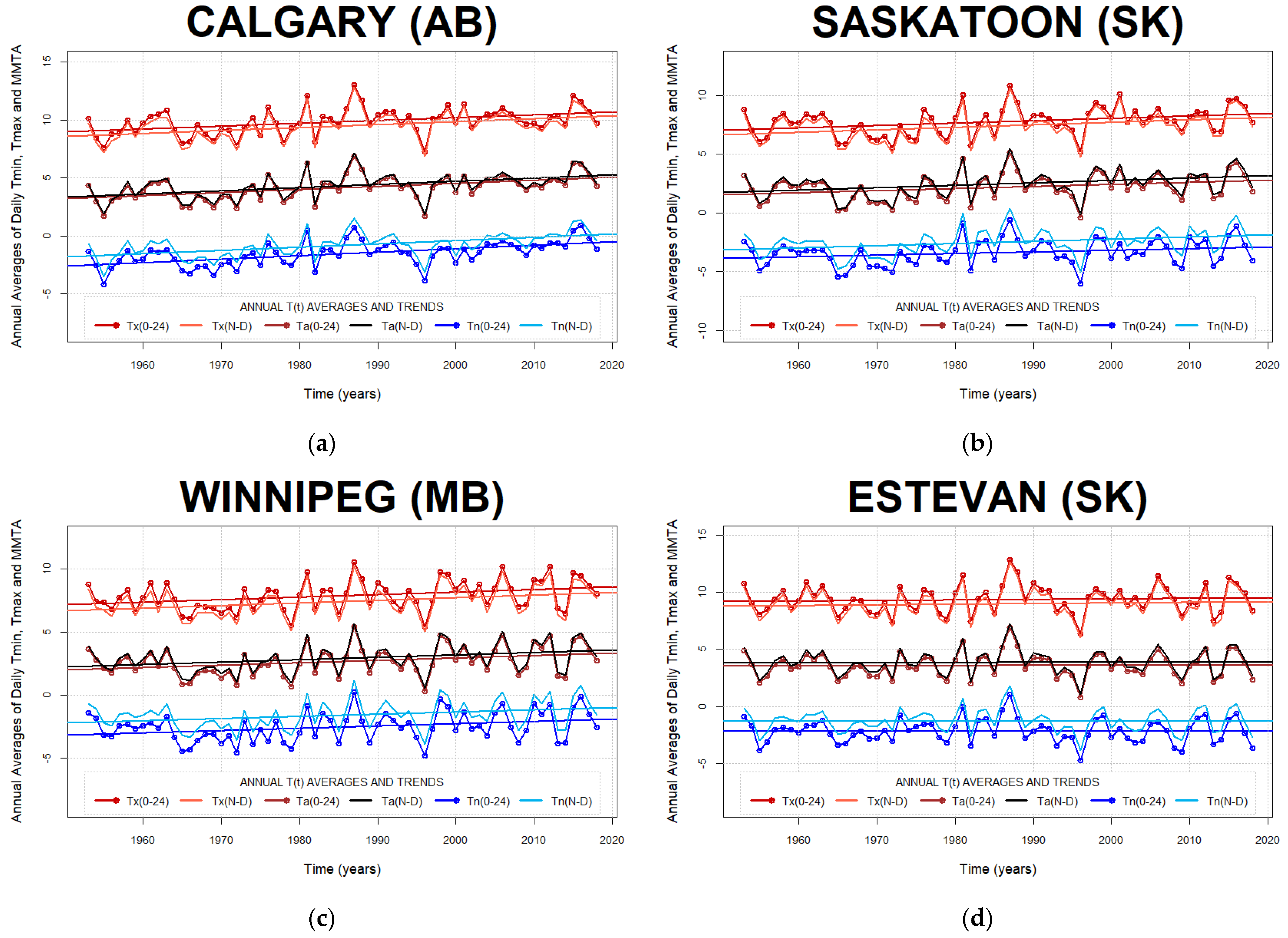

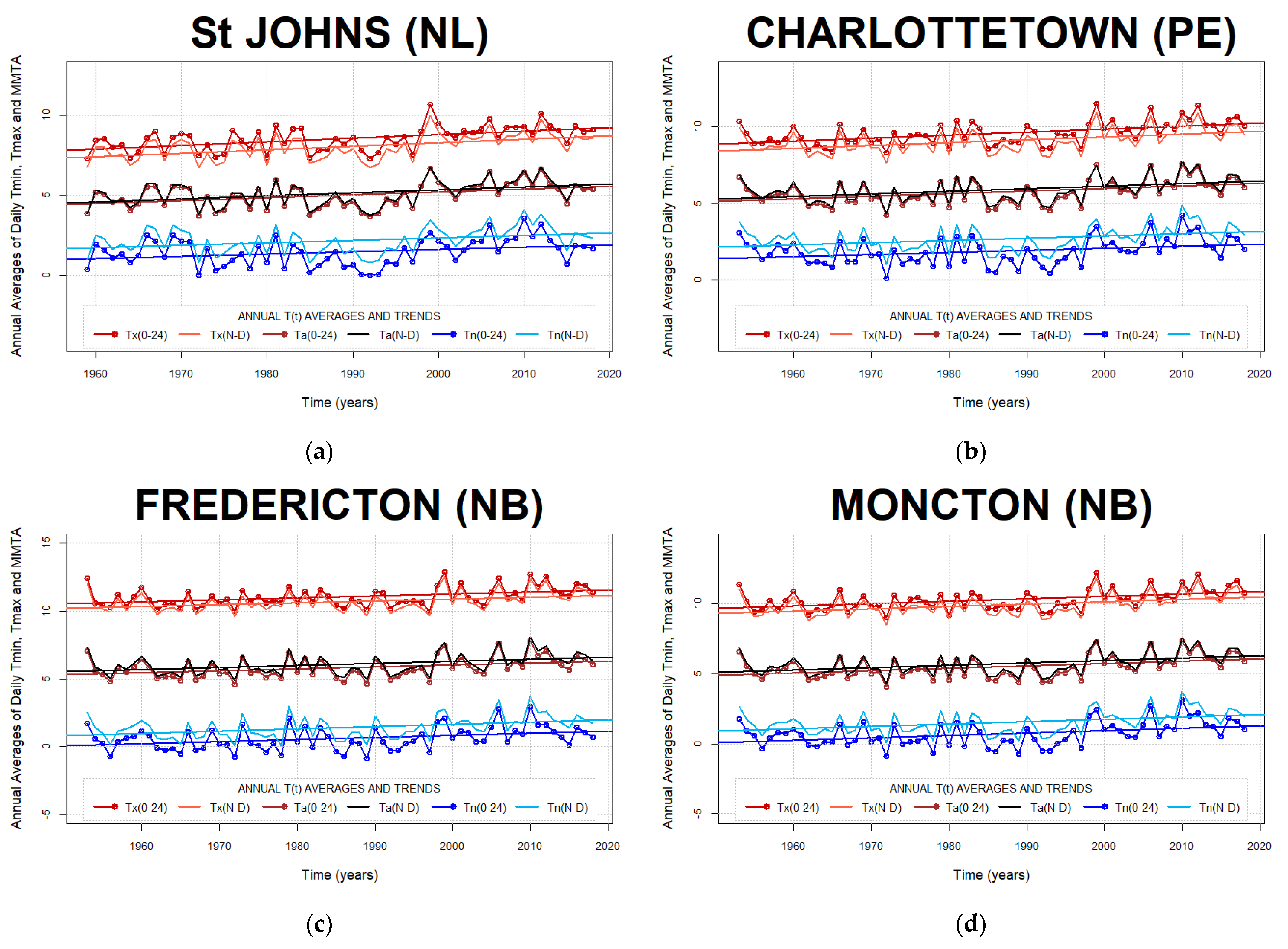

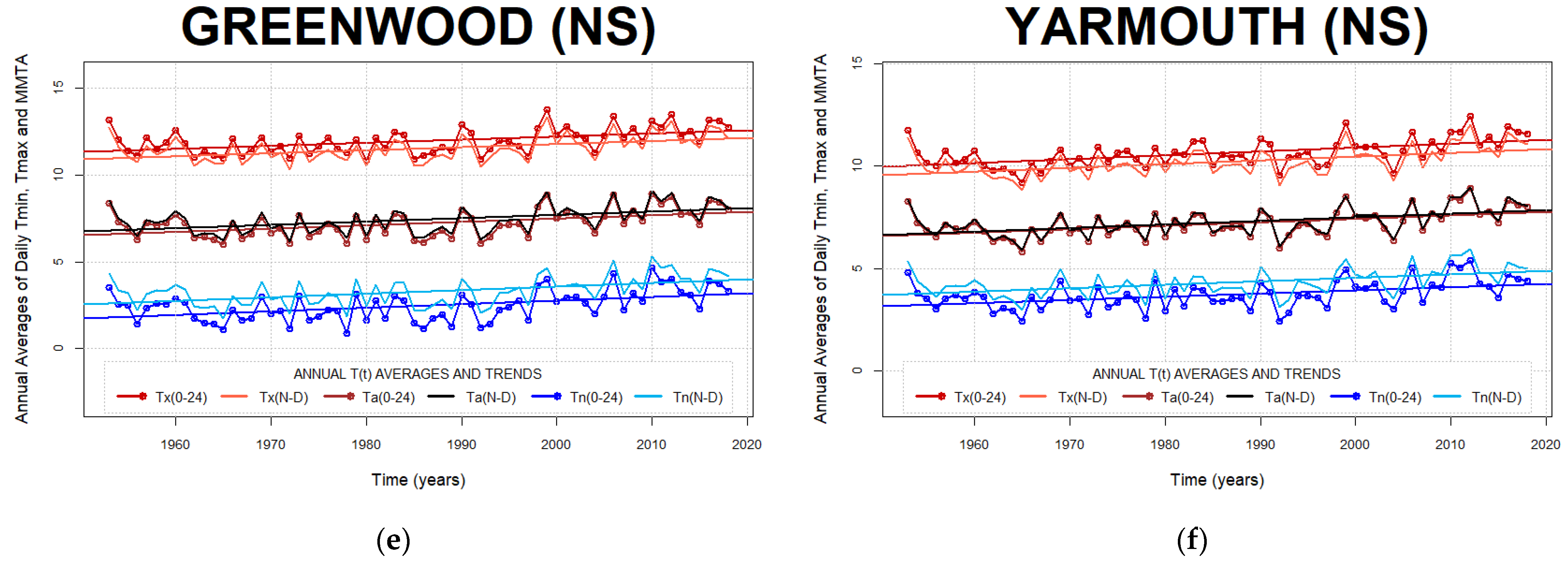

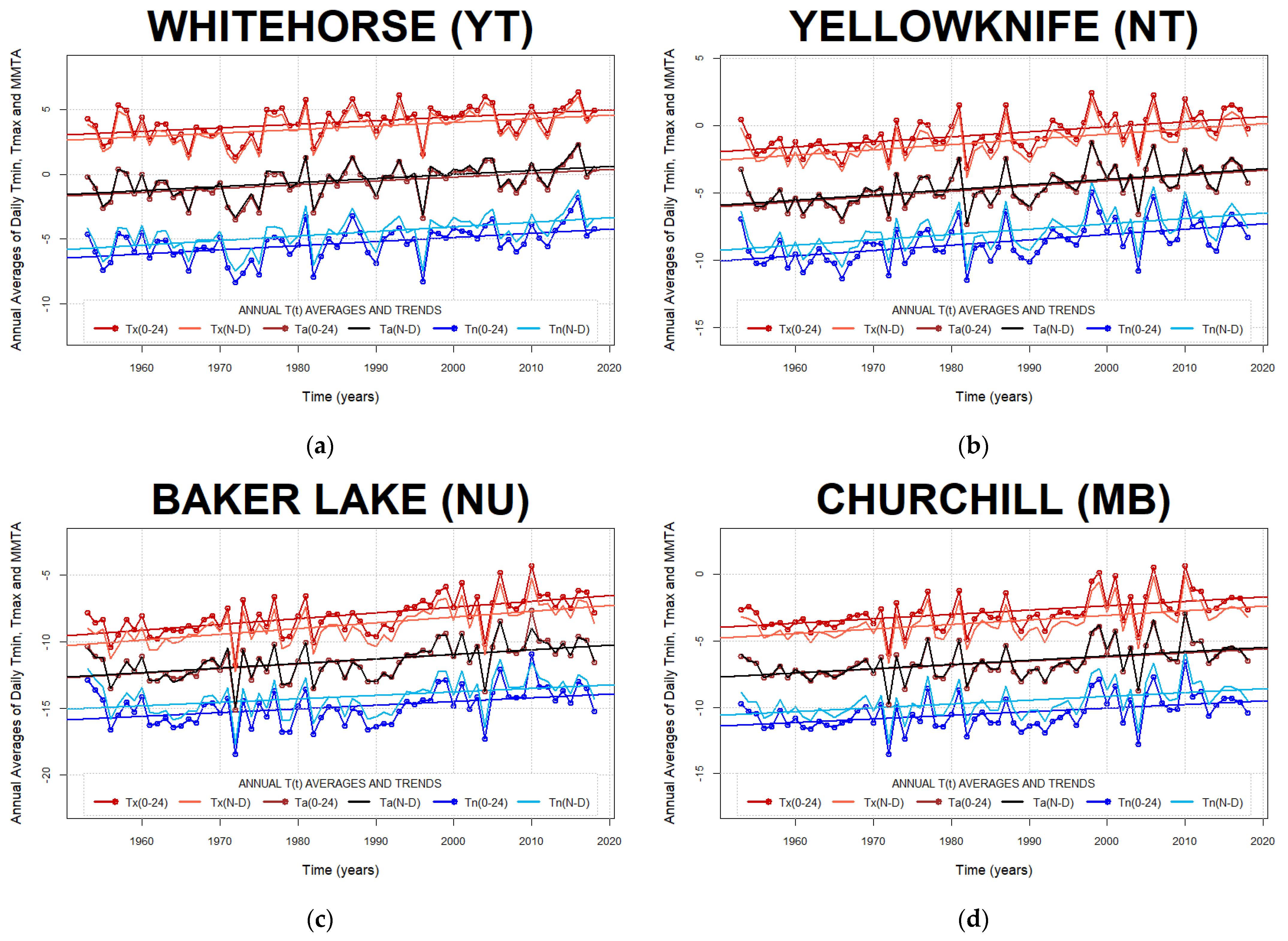

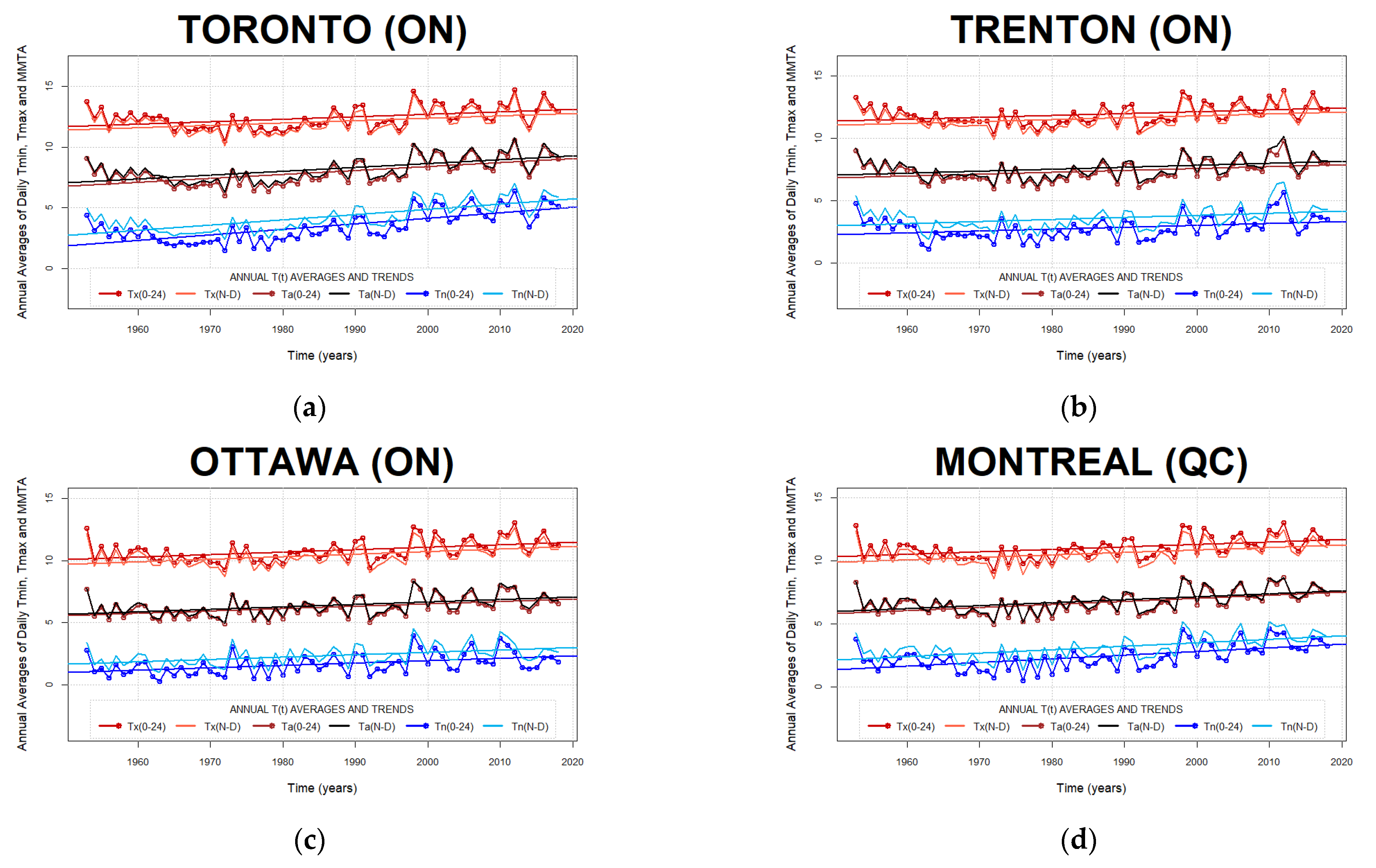

2.4. Annual averaging of COW0–24 and COWN–D Air Temperature Extrema

2.5. Analysis of Diurnal Extrema Timing

2.6. Climate Parameter Sensitivity Index (CPSI)

3. Results

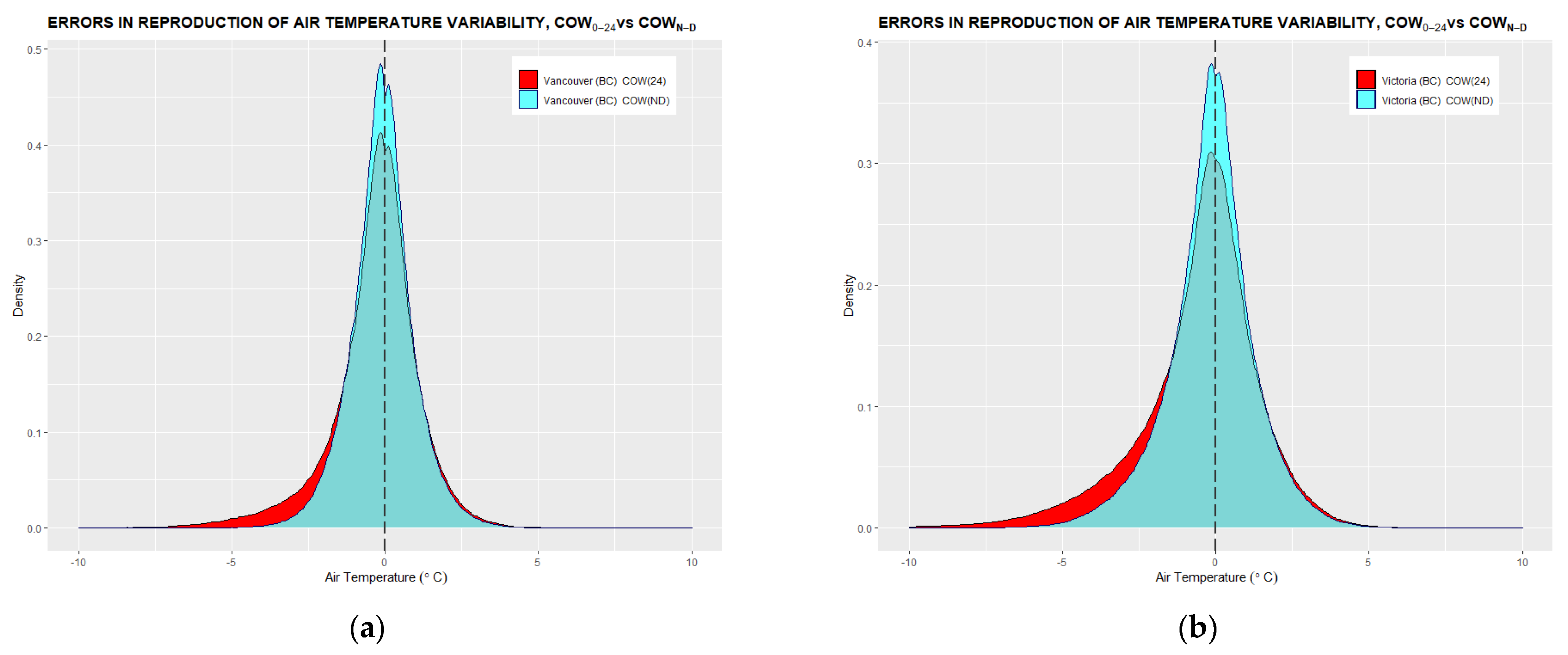

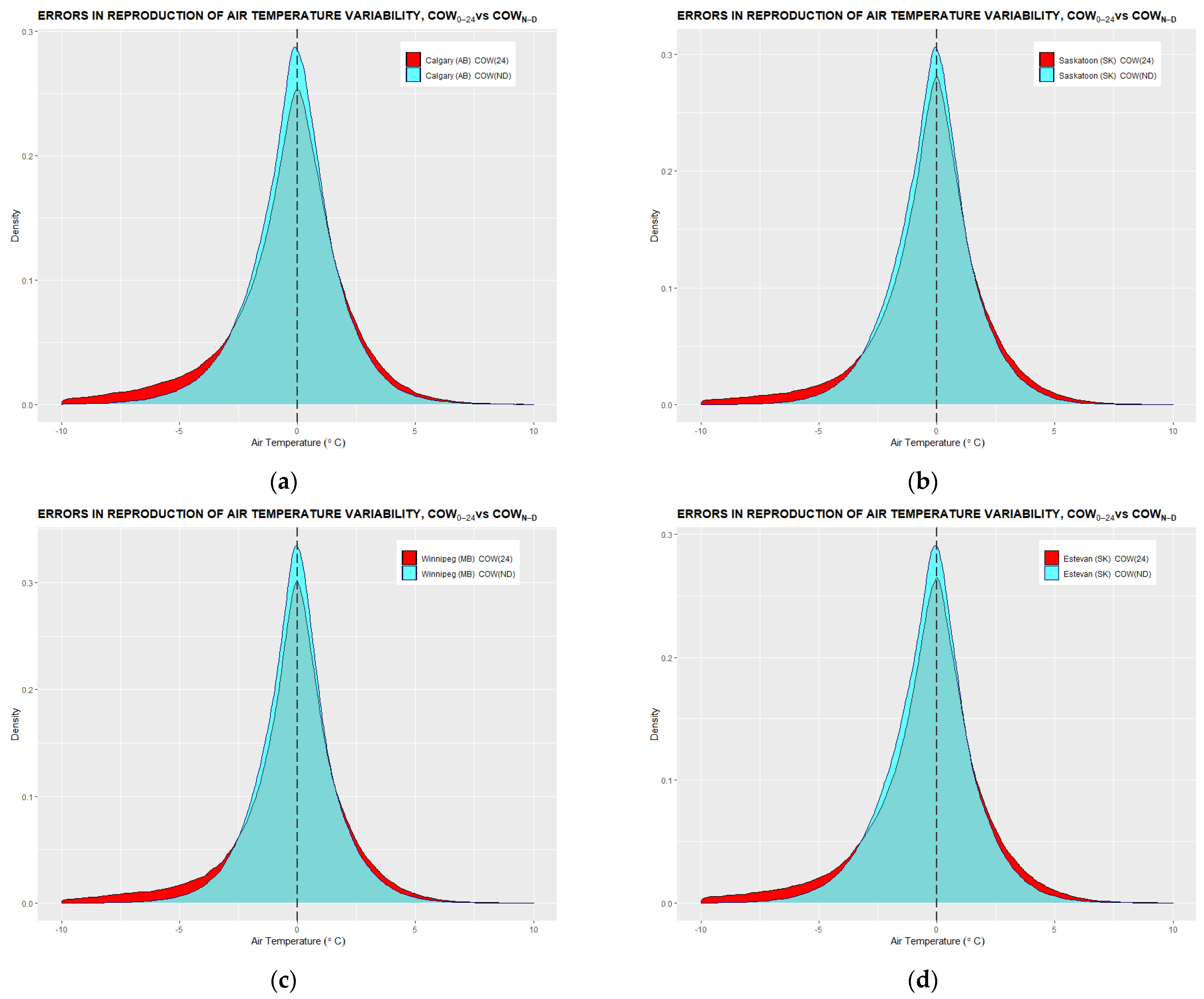

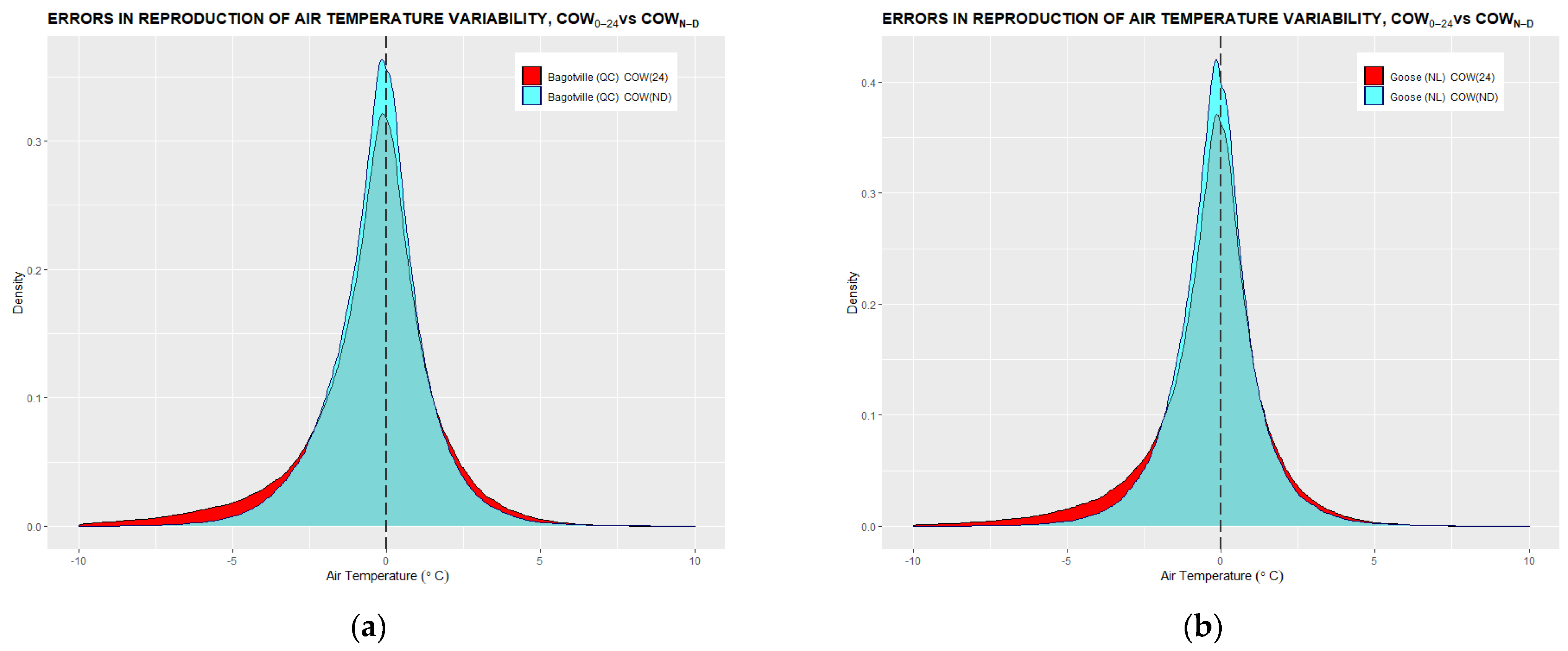

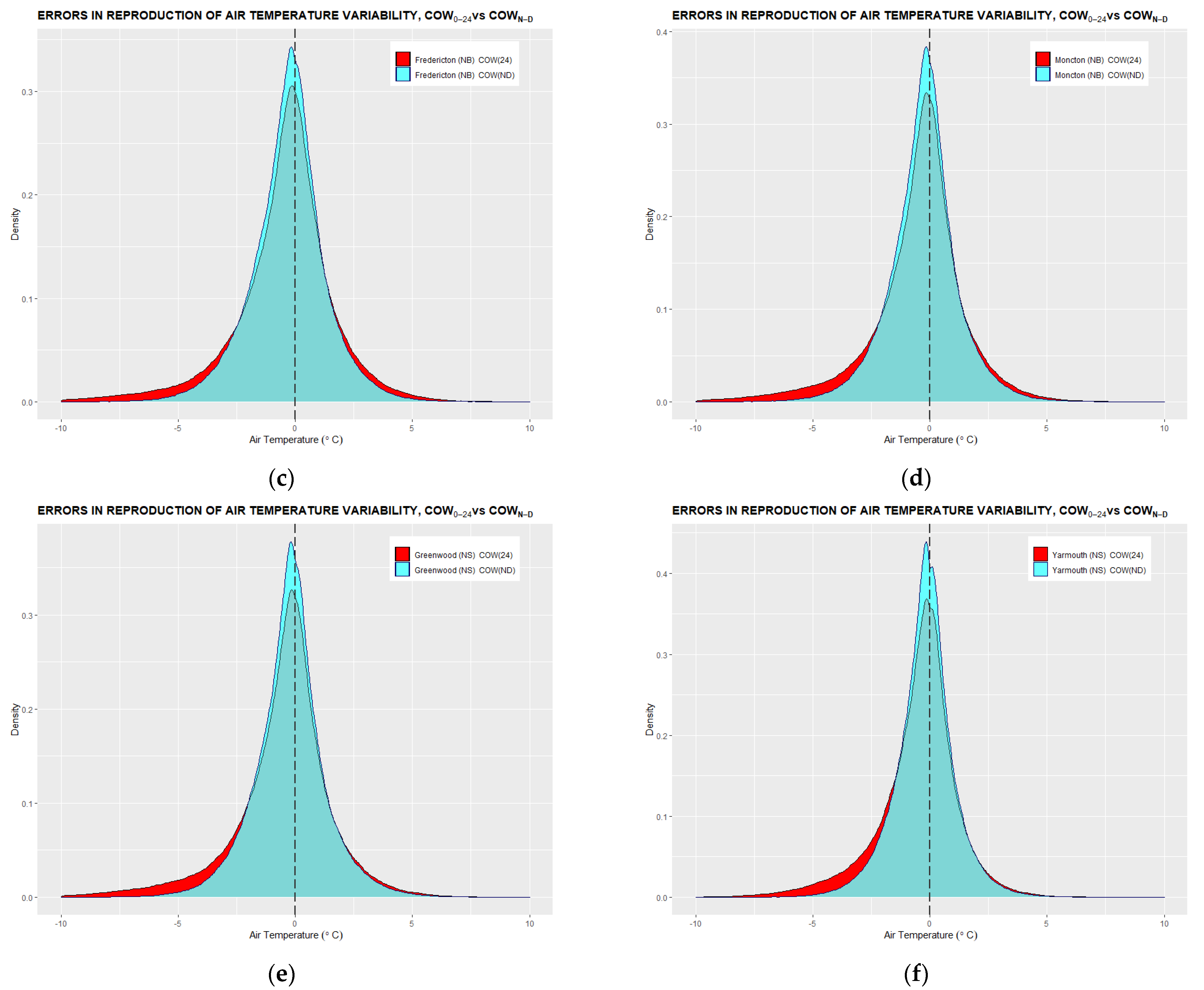

3.1. Conformity of Linear Air Temperature Tracking with Hourly Temperature Measurements

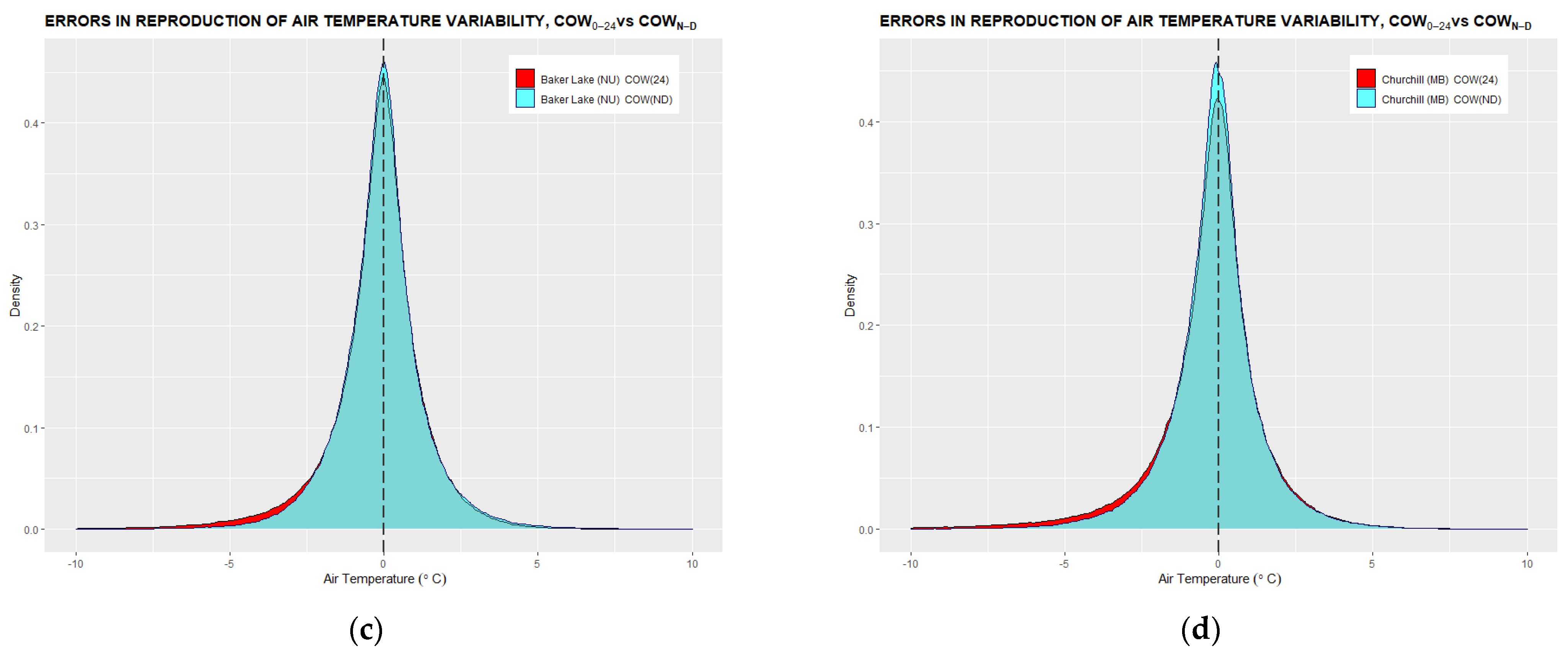

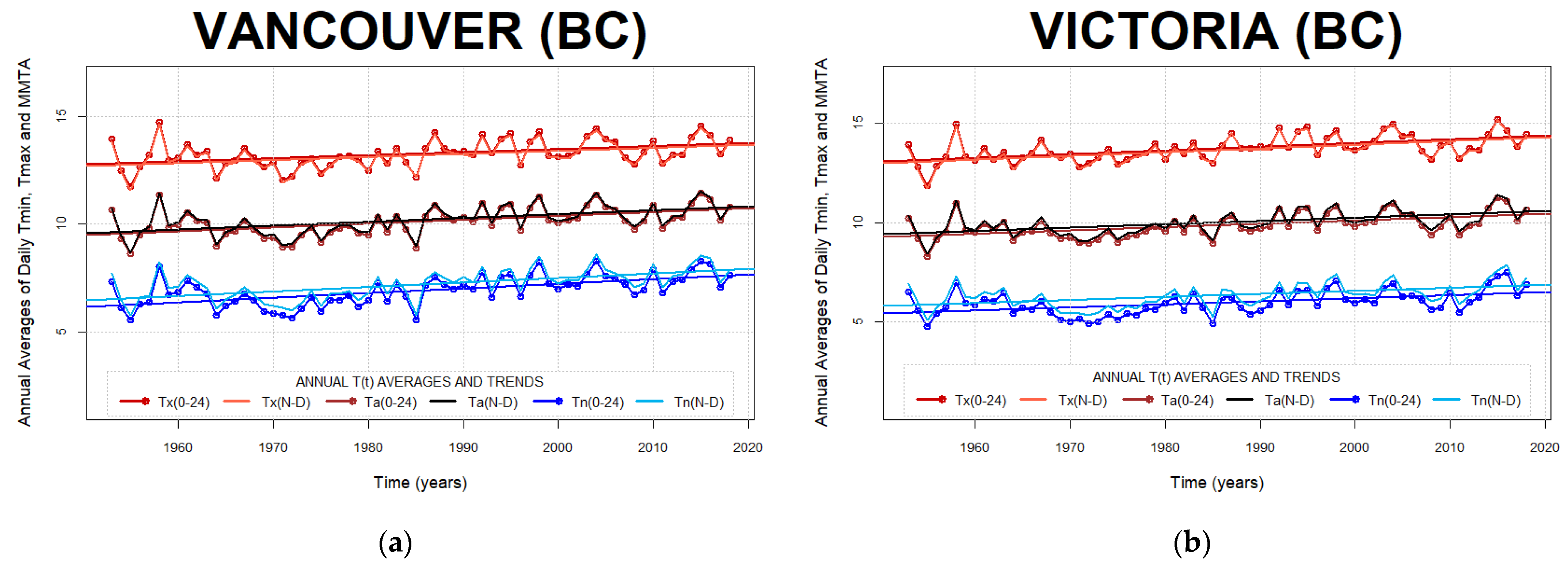

3.2. Comparison of Annual Averages of COW0–24 and COWN–D Daily Temperature Extrema

3.3. Analysis of Diurnal Extrema Timing Subpopulation Counts

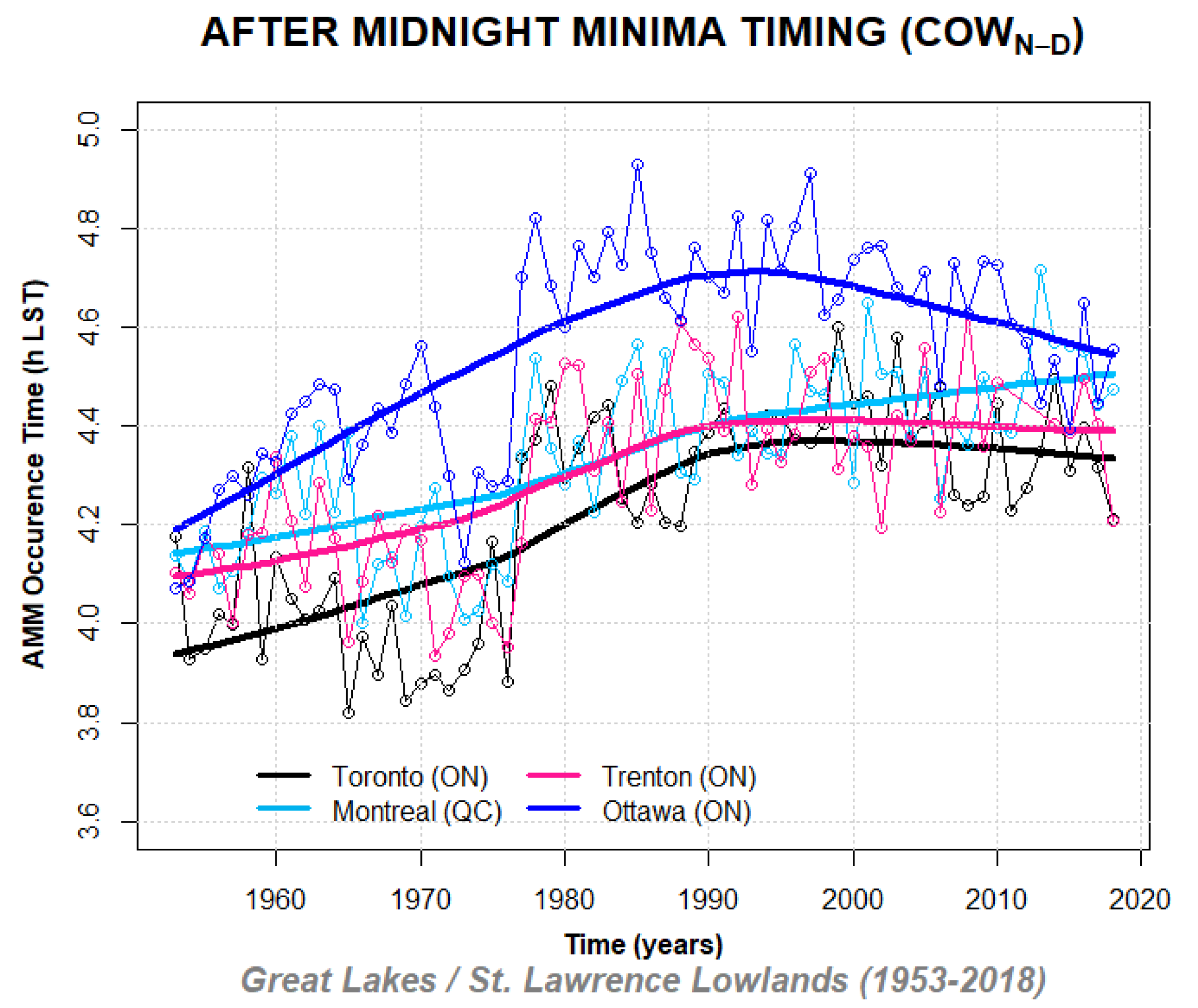

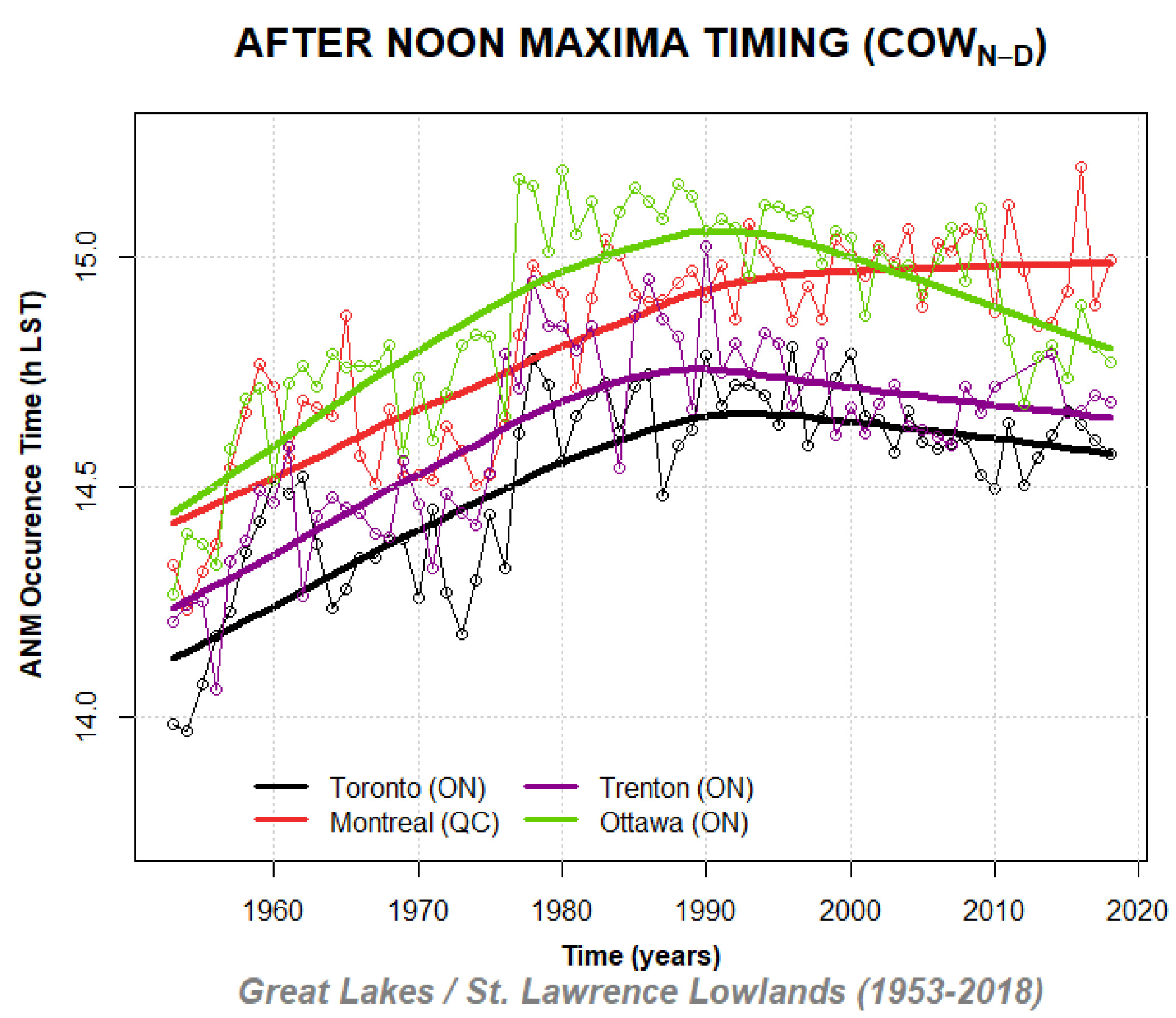

3.4. Analysis of Diurnal Extrema Timing Subpopulation Trends and Time Shifts

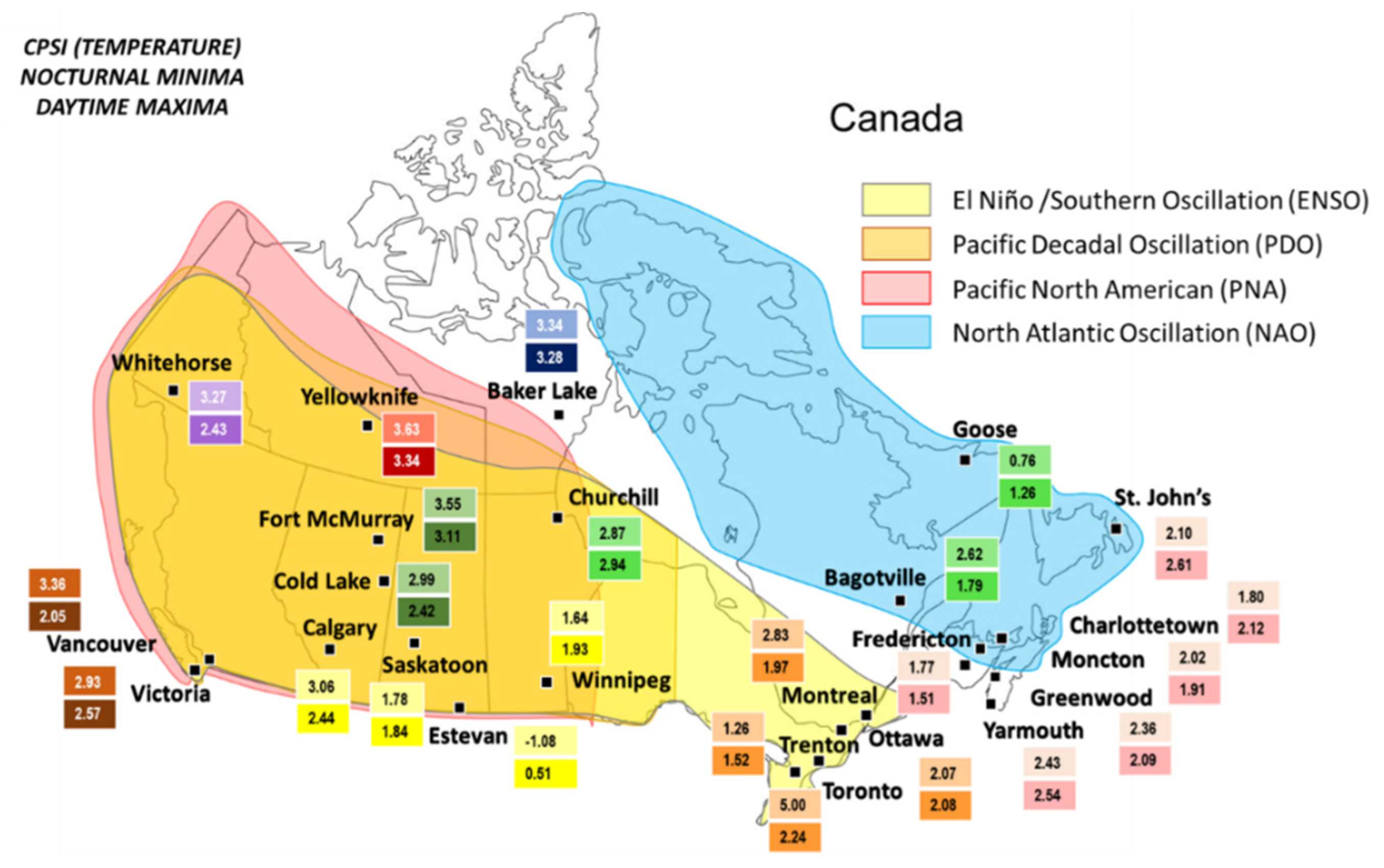

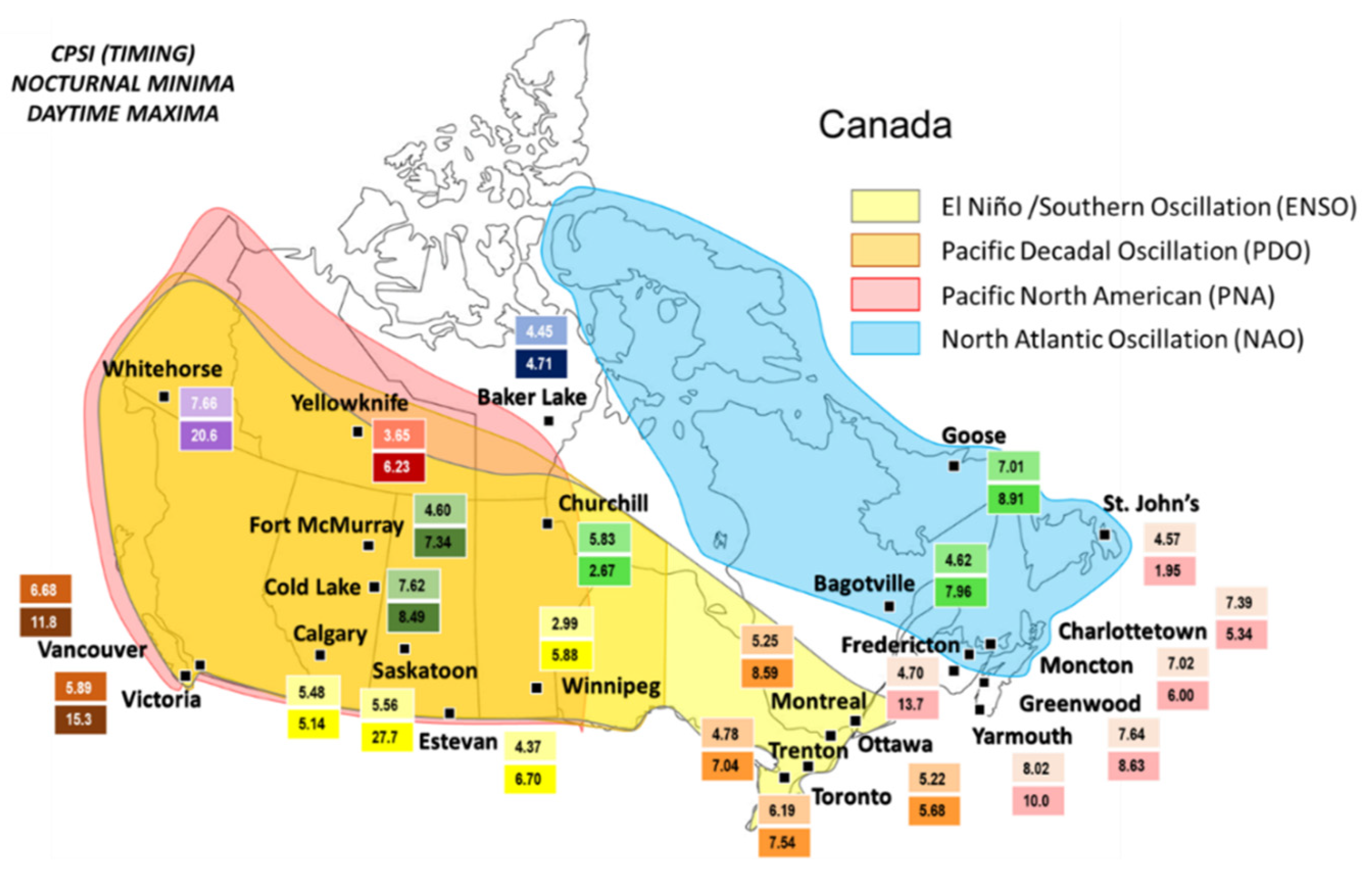

3.5. Climate Parameter Sensitivity Index (CPSI) Ranking

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Histograms of Errors in Air Temperature Tracking

Appendix B. Annual Trends of Daily Air Temperature Minima, Maxima, and Min-Max Averages

Appendix C. Histograms of Minima and Maxima Timing Migration

Appendix D. Annually Averaged After Midnight Minima (AMM) and After Noon Maxima (ANM) Timing Shifts

Appendix E. Example Calculations of Temperature and Timing Sensitivity Indices

References

- Bonacci, O.; Željković, I.; Trogrlić, R.Š.; Milković, J. Differences between true mean, daily, monthly and annual air temperatures and air temperatures calculated with three equations: A case from three Croatian stations. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2013, 114, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.M.J.; Gough, W.A.; Mohsin, T. Changes in the frequency of extreme temperature records for Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2015, 119, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C. Sampling biases in datasets of historical mean air temperature over land. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaal, L.A.; Dale, R.F. Time of observation temperature bias and “climatic change”. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1977, 16, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Gough, W.A. A comparison of climatological observing windows and their impact on detecting daily temperature extrema. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2018, 132, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, W.A.; Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Zajch, A. Sampling frequency of climate data for the determination of daily temperature and daily temperature extrema. Int. J. Clim. 2020, 40, 5451–5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Hubbard, K.G. What are daily maximum and minimum temperatures in observed climatology? Int. J. Clim. 2008, 28, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Gough, W.A. Identification of radiative and advective populations in Canadian temperature time series using the Linear Pattern Discrimination algorithm. Int. J. Clim. 2021, 41, 5100–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Howard, K.W.F.; Ćatović, Z. Modification of the degree-day formula for diurnal meltwater generation and refreezing. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2018, 131, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, D.H.C.; Levermore, G.J. New algorithm for generating hourly temperature values using daily maximum, minimum and average values from climate models. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2007, 28, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnano, L.; Boland, J.W.; Hyndman, R.J. Generation of synthetic sequences of half-hourly temperatures. Environmetrics 2008, 19, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, W.J.; Logan, J.A. A model for diurnal variation in soil and air temperature. Agric. Meteorol. 1981, 23, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N. An improved method for computing heat accumulation from daily maximum and minimum temperatures. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1978, 13, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, B.R.; Braddock, R.D. A simple method for fitting average diurnal temperature curves. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1984, 32, 107–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wann, M.; Yen, D.; Gold, H.J. Evaluation and calibration of three models for daily cycle of air temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1985, 34, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linvill, D.E. Calculating chilling hours and chill units from daily maximum and minimum temperature observations. Hort Sci. 1990, 25, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, J.E.; Schroll, R.E. An empirical model of diurnal temperature patterns. Agron. J. 1997, 89, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Amico, M.; Hornsteiner, M. A simple method for estimating daily and monthly mean temperatures from daily minima and maxima. Int. J. Clim. 2006, 26, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, F.; Bazile, E.; Soci, C.; Soubeyroux, J.-M.; Ouzeau, G.; Perrin, M. Diurnal temperature cycle deduced from extreme daily temperatures and impact over a surface reanalysis system. Adv. Sci. Res. 2015, 12, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E. A mathematical model for the generation of hourly temperatures. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1962, 16, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Allen, J.C. A modified sine wave method for calculating degree-days. Environ. Entomol. 1976, 5, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicosky, D.C.; Winkelman, L.J.; Baker, D.G. Accuracy of hourly air temperatures calculated from daily minima and maxima. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1989, 46, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, W.R., Jr. A Method for Estimating Missing Hourly Temperatures Using Daily Maximum and Minimum Temperatures; USAF Environmental Technical Applications Center, Scott Air Force Base: St. Louis, IL, USA, 1991; USAFETAC/PR-91/017. [Google Scholar]

- Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Howard, K.W.F.; Gough, W.A.; Catovic, Z. A modified degree-day method for volume and timing estimation of snowmelt and refreezing. In Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Hydrology, American Meteorological Society, Boston, MA, USA, 15 January 2020; p. 368200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Gough, W.A. A new approach to air temperature analysis. In Proceedings of the 32nd Conference on Climate Variability and Change, American Meteorological Society, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 7 January 2019; p. 352891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.A.; Milewska, E.J.; Hopkinson, R.; Malone, L. Bias in minimum temperature introduced by a redefinition of the climatological day at the Canadian synoptic stations. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 2009, 48, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, R.F.; McKenney, D.W.; Daniel, W.; Milewska, E.J.; Hutchinson, M.F.; Papadopol, P.; Vincent, L.A. Impact of aligning climatological day on gridding daily maximum-minimum temperatures and precipitation over Canada. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 2011, 50, 1654–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.S. Time limits of the day affecting records of minimum temperature. Mon. Weather Rev. 1934, 62, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, M.J. Observation-time-dependent biases and departures for daily minimum and maximum air temperatures. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2001, 41, 588–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. About the Data. Available online: https://climate.weather.gc.ca/about_the_data_index_e.html (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Government of Canada. Historical Climate Data. Available online: https://climate.weather.gc.ca/historical_data/search_historic_data_e.html (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Core Team, R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsal, B.; Shabbar, A. Large-Scale Climate Oscillations Influencing Canada, 1900-2008. Canadian Biodiversity: Ecosystem Status and Trends 2010. Technical Thematic Report No.4; Canadian Councils of Resource Ministers: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011; Available online: http://www.biodivcanada.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=137E1147-0 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Vincent, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Brown, R.D.; Feng, Y.; Mekis, E.; Milewska, E.J.; Wan, H.; Wang, X.L. Observed trends in Canada’s climate and influence of low-frequency variability modes. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 4545–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, W.A.; He, D. Diurnal temperature asymmetries and fog at Churchill, Manitoba. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2015, 121, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.; Gough, W.A. Air mass distribution and the heterogeneity of the climate change signal in the Hudson Bay/Foxe Basin region, Canada. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2016, 125, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Provinces & Territories | Location | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°W) | Data Range | Missing Data (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | Calgary | 51.1139 | 114.0203 | 1953–2018 | 0.04 |

| Cold Lake | 54.4167 | 110.2833 | 1955–2018 | 0.10 | |

| Fort McMurray | 56.6500 | 111.2167 | 1953–2018 | 0.35 | |

| British Columbia | Vancouver | 49.1950 | 123.1819 | 1953–2018 | 0.03 |

| Victoria | 48.6472 | 123.4258 | 1953–2018 | 0.07 | |

| Manitoba | Churchill | 58.7392 | 94.0664 | 1953–2018 | 0.17 |

| Winnipeg | 49.9167 | 97.2333 | 1953–2018 | 0.06 | |

| New Brunswick | Fredericton | 45.8776 | 66.5279 | 1953–2018 | 0.13 |

| Moncton | 46.1053 | 64.6838 | 1953–2018 | 0.03 | |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | Goose | 53.7083 | 57.0350 | 1953–2018 | 0.06 |

| St. John’s | 47.6222 | 52.7428 | 1959–2018 | 0.05 | |

| Nova Scotia | Greenwood | 44.9833 | 64.9167 | 1953–2018 | 0.05 |

| Yarmouth | 43.8308 | 66.0886 | 1953–2018 | 0.16 | |

| Ontario | Ottawa | 45.3225 | 75.6692 | 1953–2018 | 0.05 |

| Toronto | 43.6772 | 79.6306 | 1953–2018 | 0.03 | |

| Trenton | 44.1167 | 77.5333 | 1953–2018 | 1.49 | |

| Prince Edward Island | Charlottetown | 46.1719 | 63.0743 | 1953–2018 | 0.13 |

| Quebec | Bagotville | 48.3333 | 71.0000 | 1953–2018 | 0.04 |

| Montreal | 45.2814 | 73.4427 | 1953–2018 | 0.03 | |

| Saskatchewan | Estevan | 49.2167 | 102.9667 | 1953–2018 | 0.07 |

| Saskatoon | 52.1667 | 106.7167 | 1953–2018 | 0.06 | |

| Northwest Territories | Yellowknife | 62.2746 | 114.2625 | 1953–2018 | 0.05 |

| Nunavut | Baker Lake | 64.2989 | 96.0778 | 1963–2018 | 0.69 |

| Yukon | Whitehorse | 60.7094 | 135.0686 | 1953–2018 | 0.04 |

| Provinces & Territories | Location | COW0–24 | COWN–D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (°C) | Std Dev (°C) | Mean (°C) | Std Dev (°C) | ||

| Alberta | Calgary | −0.49 | 2.68 | −0.18 | 1.98 |

| Cold Lake | −0.30 | 2.14 | −0.11 | 1.56 | |

| Fort McMurray | −0.33 | 2.45 | −0.12 | 1.77 | |

| British Columbia | Vancouver | −0.54 | 1.99 | −0.15 | 1.42 |

| Victoria | −0.32 | 1.44 | −0.09 | 1.04 | |

| Manitoba | Churchill | −0.31 | 1.83 | −0.14 | 1.50 |

| Winnipeg | −0.36 | 2.41 | −0.09 | 1.67 | |

| New Brunswick | Fredericton | −0.48 | 2.20 | −0.30 | 1.62 |

| Moncton | −0.53 | 2.09 | −0.27 | 1.50 | |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | Goose | −0.44 | 1.93 | −0.21 | 1.45 |

| St. John’s | −0.70 | 1.82 | −0.35 | 1.35 | |

| Nova Scotia | Greenwood | −0.54 | 2.14 | −0.23 | 1.55 |

| Yarmouth | −0.52 | 1.75 | −0.23 | 1.30 | |

| Ontario | Ottawa | −0.37 | 1.91 | −0.18 | 1.41 |

| Toronto | −0.44 | 2.05 | −0.18 | 1.45 | |

| Trenton | −0.36 | 2.09 | −0.07 | 1.53 | |

| Prince Edward Island | Charlottetown | −0.49 | 1.77 | −0.24 | 1.31 |

| Quebec | Bagotville | −0.50 | 2.17 | −0.26 | 1.64 |

| Montreal | −0.28 | 1.83 | −0.06 | 1.36 | |

| Saskatchewan | Estevan | −0.52 | 2.65 | −0.30 | 1.89 |

| Saskatoon | −0.36 | 2.48 | −0.17 | 1.77 | |

| Northwest Territories | Yellowknife | −0.13 | 1.70 | −0.05 | 1.40 |

| Nunavut | Baker Lake | −0.08 | 1.59 | −0.05 | 1.42 |

| Yukon | Whitehorse | −0.12 | 1.97 | −0.04 | 1.58 |

| Canadian Averages | −0.40 | 2.07 | −0.17 | 1.53 | |

| Provinces & Territories | Location | ΔTmin | ΔTmax | ΔMMA | ΔDTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | ||

| Alberta | Calgary | −0.74 | 0.35 | −0.19 | 1.01 |

| Cold Lake | −0.70 | 0.32 | −0.19 | 1.02 | |

| Fort McMurray | −0.89 | 0.37 | −0.25 | 1.25 | |

| British Columbia | Vancouver | −0.27 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.35 |

| Victoria | −0.36 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.44 | |

| Manitoba | Churchill | −0.87 | 0.75 | −0.05 | 1.62 |

| Winnipeg | −0.96 | 0.44 | −0.26 | 1.40 | |

| New Brunswick | Fredericton | −0.82 | 0.33 | −0.25 | 1.15 |

| Moncton | −0.82 | 0.39 | −0.22 | 1.21 | |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | Goose | −0.79 | 0.48 | −0.16 | 1.26 |

| St. John’s | −0.72 | 0.50 | −0.11 | 1.22 | |

| Nova Scotia | Greenwood | −0.82 | 0.42 | −0.20 | 1.25 |

| Yarmouth | −0.59 | 0.43 | −0.08 | 1.02 | |

| Ontario | Ottawa | −0.69 | 0.39 | −0.15 | 1.09 |

| Toronto | −0.77 | 0.31 | −0.23 | 1.08 | |

| Trenton | −0.77 | 0.32 | −0.22 | 1.09 | |

| Prince Edward Island | Charlottetown | −0.78 | 0.48 | −0.15 | 1.26 |

| Quebec | Bagotville | −0.95 | 0.52 | −0.21 | 1.45 |

| Montreal | −0.70 | 0.44 | −0.13 | 1.14 | |

| Saskatchewan | Estevan | −0.27 | 0.40 | −0.27 | 1.27 |

| Saskatoon | −0.89 | 0.38 | −0.25 | 1.27 | |

| Northwest Territories | Yellowknife | −0.80 | 0.60 | −0.10 | 1.40 |

| Nunavut | Baker Lake | −0.73 | 0.75 | 0.005 | 1.48 |

| Yukon | Whitehorse | −0.75 | 0.42 | −0.16 | 1.17 |

| Canadian Averages | −0.73 | 0.41 | −0.17 | 1.16 |

| Provinces & Territories | Location | Total BMMtn | Migrated BMMtn | Total BNMtx | Migrated BNMtx | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (n) | (%) | ||

| Alberta | Calgary | 270 | −120 | 44.4 | 146 | −42 | 28.8 |

| Cold Lake | 174 | −7 | 9.5 | 141 | −34 | 24.1 | |

| Fort McMurray | 219 | −40 | 18.3 | 123 | −26 | 21.1 | |

| British Columbia | Vancouver | 311 | −111 | 35.7 | 220 | −93 | 42.3 |

| Victoria | 390 | −149 | 38.2 | 242 | −123 | 50.8 | |

| Manitoba | Churchill | 453 | −140 | 30.9 | 431 | −106 | 24.6 |

| Winnipeg | 224 | −45 | 20.1 | 159 | −18 | 11.3 | |

| New Brunswick | Fredericton | 232 | −13 | 5.6 | 162 | −46 | 28.4 |

| Moncton | 298 | −55 | 18.5 | 236 | −70 | 29.7 | |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | Goose | 281 | −71 | 25.3 | 196 | −28 | 14.3 |

| St. John’s | 589 | −120 | 20.4 | 508 | −97 | 19.1 | |

| Nova Scotia | Greenwood | 337 | −102 | 30.3 | 280 | −100 | 35.1 |

| Yarmouth | 498 | −130 | 26.1 | 465 | −176 | 37.8 | |

| Ontario | Ottawa | 261 | −58 | 22.2 | 174 | −47 | 27.0 |

| Toronto | 284 | −72 | 25.4 | 235 | −79 | 31.9 | |

| Trenton | 271 | −30 | 11.1 | 250 | −69 | 27.6 | |

| Prince Edward Island | Charlottetown | 460 | −108 | 23.5 | 382 | −124 | 32.5 |

| Quebec | Bagotville | 333 | −77 | 23.1 | 283 | −120 | 42.4 |

| Montreal | 246 | −61 | 24.8 | 212 | −66 | 31.1 | |

| Saskatchewan | Estevan | 228 | −79 | 34.6 | 149 | −56 | 37.6 |

| Saskatoon | 214 | −37 | 17.3 | 159 | −68 | 42.8 | |

| Northwest Territories | Yellowknife | 339 | −47 | 13.9 | 214 | −47 | 22.0 |

| Nunavut | Baker Lake | 560 | −176 | 31.4 | 406 | −113 | 27.8 |

| Yukon | Whitehorse | 279 | −80 | 28.7 | 181 | −104 | 57.5 |

| Canadian Averages | 323 | −80 | 24.1 | 248 | −77 | 31.2 | |

| Provinces & Territories | Location | AMMtn Slopes | DETtn | ANMtx Slopes | DETtx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (h/y) | (h) | (h/y) | (h) | ||

| Alberta | Calgary | 6.6×10-3 | 0.44 | 5.5×10-3 | 0.36 |

| Cold Lake | 9.5×10-3 | 0.61 | 9.3×10-3 | 0.60 | |

| Fort McMurray | 6.3×10-3 | 0.42 | 6.7×10-3 | 0.44 | |

| British Columbia | Vancouver | 8.1×10-3 | 0.53 | 7.2×10-3 | 0.48 |

| Victoria | 7.1×10-3 | 0.47 | 9.3×10-3 | 0.61 | |

| Manitoba | Churchill | 8.0×10-3 | 0.53 | 2.8×10-3 | 0.18 |

| Winnipeg | 3.6×10-3 | 0.24 | 5.3×10-3 | 0.35 | |

| New Brunswick | Fredericton | 6.8×10-3 | 0.38 | 6.3×10-3 | 0.42 |

| Moncton | 8.5×10-3 | 0.56 | 6.7×10-3 | 0.38 | |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | Goose | 8.4×10-3 | 0.55 | 9.5×10-3 | 0.63 |

| St. John’s | 6.1×10-3 | 0.40 | 2.3×10-3 | 0.14 | |

| Nova Scotia | Greenwood | 9.3×10-3 | 0.61 | 9.2×10-3 | 0.61 |

| Yarmouth | 9.3×10-3 | 0.61 | 7.6×10-3 | 0.50 | |

| Ontario | Ottawa | 6.3×10-3 | 0.42 | 6.0×10-3 | 0.40 |

| Toronto | 7.5×10-3 | 0.50 | 6.9×10-3 | 0.46 | |

| Trenton | 6.1×10-3 | 0.38 | 6.7×10-3 | 0.42 | |

| Prince Edward Island | Charlottetown | 8.9×10-3 | 0.59 | 5.7×10-3 | 0.38 |

| Quebec | Bagotville | 7.0×10-3 | 0.46 | 9.6×10-3 | 0.63 |

| Montreal | 6.4×10-3 | 0.42 | 9.1×10-3 | 0.60 | |

| Saskatchewan | Estevan | 5.3×10-3 | 0.35 | 5.1×10-3 | 0.34 |

| Saskatoon | 6.7×10-3 | 0.44 | 2.1×10-2 | 1.39 | |

| Northwest Territories | Yellowknife | 5.5×10-3 | 0.36 | 8.5×10-3 | 0.56 |

| Nunavut | Baker Lake | 8.0×10-3 | 0.44 | 1.3×10-3 | 0.09 |

| Yukon | Whitehorse | 1.0×10-3 | 0.69 | 2.2×10-2 | 1.44 |

| Canadian Averages | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| Provinces & Territories | Location | NTn | AMMtn | DTx | ANMtx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | ||

| Alberta | Calgary | 3.06 | 5.48 | 2.44 | 5.14 |

| Cold Lake | 2.99 | 7.62 | 2.42 | 8.49 | |

| Fort McMurray | 3.55 | 4.60 | 3.11 | 7.34 | |

| British Columbia | Vancouver | 3.36 | 6.68 | 2.05 | 11.81 |

| Victoria | 2.93 | 5.89 | 2.57 | 15.27 | |

| Manitoba | Churchill | 2.87 | 5.83 | 2.94 | 2.67 |

| Winnipeg | 1.64 | 2.99 | 1.93 | 5.88 | |

| New Brunswick | Fredericton | 1.77 | 4.70 | 1.51 | 13.69 |

| Moncton | 2.02 | 7.02 | 1.91 | 6.00 | |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | Goose | 0.76 | 7.01 | 1.26 | 8.91 |

| St. John’s | 2.10 | 4.57 | 2.61 | 1.95 | |

| Nova Scotia | Greenwood | 2.36 | 7.64 | 2.09 | 8.63 |

| Yarmouth | 2.43 | 8.02 | 2.54 | 10.00 | |

| Ontario | Ottawa | 2.07 | 5.22 | 2.08 | 5.68 |

| Toronto | 5.00 | 6.19 | 2.24 | 7.54 | |

| Trenton | 1.26 | 4.78 | 1.52 | 7.04 | |

| Prince Edward Island | Charlottetown | 1.80 | 7.39 | 2.12 | 5.34 |

| Quebec | Bagotville | 2.62 | 4.62 | 1.79 | 7.96 |

| Montreal | 2.83 | 5.25 | 1.97 | 8.59 | |

| Saskatchewan | Estevan | −1.08 | 4.37 | 0.51 | 6.70 |

| Saskatoon | 1.78 | 5.56 | 1.84 | 27.75 | |

| Northwest Territories | Yellowknife | 3.63 | 3.65 | 3.34 | 6.23 |

| Nunavut | Baker Lake | 3.34 | 4.45 | 3.28 | 4.71 |

| Yukon | Whitehorse | 3.27 | 7.66 | 2.43 | 20.63 |

| Canadian Averages | 2.43 | 5.72 | 2.19 | 8.91 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Gough, W.A. Diurnal Extrema Timing—A New Climatological Parameter? Climate 2022, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10010005

Žaknić-Ćatović A, Gough WA. Diurnal Extrema Timing—A New Climatological Parameter? Climate. 2022; 10(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleŽaknić-Ćatović, Ana, and William A. Gough. 2022. "Diurnal Extrema Timing—A New Climatological Parameter?" Climate 10, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10010005

APA StyleŽaknić-Ćatović, A., & Gough, W. A. (2022). Diurnal Extrema Timing—A New Climatological Parameter? Climate, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10010005