Each module is interfaced with specific physical systems that collect and process data:

The integration of these three modules enables a more robust and context-aware approach to workplace safety, overcoming the limitations of individual subsystems operating in isolation. In the following subsections, we provide further details on the functionalities of each module and describe the proof-of-concept implementation developed to validate the feasibility of the proposed approach.

3.1. Localization Module

The Localization Module is responsible for interacting with commercial RTLS to enable real-time worker and vehicle tracking. The system distinguishes three categories of tracked entities: workers, visitors, and forklifts (representing indoor vehicles). Each entity is equipped with a tag that continuously transmits localization data. This data, including the tag ID, object type, and coordinates, is forwarded to the Aggregation Module for further processing.

The module is designed to be flexible and expandable, ensuring compatibility with different RTLS. Integration is achieved through a standardized interface based on RESTful APIs. New RTLS solutions can be added by developing a dedicated plug-in that implements the required communication protocol. This modular approach abstracts implementation details while handling initialization, data processing, and tag management uniformly.

Our proof-of-concept implementation integrates the commercial

UbiTrack UWB Positioning System (

https://www.ubitrack.com/products/starter-kit (accessed on 30 September 2025)), priced at approximately

$2400. The manufacturer specifies a localization accuracy of under 30 cm, supporting both Time Difference of Arrival (TDoA) and Two-Way Ranging (TWR) positioning methods. The system operates at up to 10 Hz, making it suitable for real-time tracking. Additionally, its support for REST APIs facilitates seamless integration into our safety monitoring framework.

The UbiTrack Starter Kit includes four anchors, covering up to 900 , along with six tags designed for different use cases:

Wristband Tag: Suitable for tracking personnel.

Location Badge: Worn as a necklace, ideal for visitor identification.

Location Tag: A rugged tag attachable to objects, used for tracking equipment and vehicles (e.g., forklifts).

For testing, the system was deployed in the

Crosslab—Cloud Computing, Big Data, and Cybersecurity (

https://crosslab.dii.unipi.it/(accessed on 30 September 2025)) laboratory at the University of Pisa. This environment replicates industrial conditions, featuring metal structures and electromagnetic interference sources. The four UWB anchors were installed on tripods at fixed heights.

To evaluate the RTLS performance, we conducted both static and dynamic tests using all available tags. Tests were performed with different anchor heights and monitored area sizes to assess their impact on accuracy [

19].

In static tests, the tags were placed at fixed positions, and the average localization error was measured.

Table 1 presents the results.

As observed, reducing the monitored area decreases the localization error by approximately 20% for the same anchor height. Similarly, lowering the anchor height improves accuracy by nearly 60% for a given area size. This indicates that anchor placement height has a greater impact on accuracy than the covered area.

For dynamic tests, we set the parameters that yielded the lowest error in static tests (i.e., a 28

area with 2.0 m anchor height). A person carried all six tags while moving them along predefined linear trajectories. Two test runs were conducted following perpendicular paths, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

To enhance localization accuracy, we implemented two filtering techniques:

Table 2 presents the dynamic test results and reports average localization errors for the six tags across different filtering configurations: No Filter (NF), Kalman Filter (KF), and Kalman Filter with Exponential Moving Average (KEF).

Applying the Kalman Filter reduced localization error by approximately 20% along the X-axis and 13% along the Y-axis. The combined Kalman Filter and Exponential Moving Average (KEF) further improved accuracy, achieving a 24% reduction on the X-axis and 23% on the Y-axis. These results highlight the effectiveness of post-processing techniques in refining RTLS-based localization.

3.2. AI Module

The AI module is responsible for analyzing images captured by surveillance cameras to detect the presence of workers, verify correct PPE usage, and identify forklifts operating within the monitored area. The extracted information is sent to the Aggregation Module, where it is combined with localization data to enforce safety rules and trigger alerts when necessary.

The PPE detection component is based on the architecture proposed in [

2] and recently improved in [

10], which adopts an edge computing approach. Images are processed locally on an embedded system deployed near the camera, eliminating the need to offload data to the cloud. This ensures privacy preservation and system resilience to network failures.

YOLOv8 was selected as the core object detection model due to its high maturity, active community support, and ease of adaptation to different hardware platforms. Various YOLOv8 configurations were tested, differing in model complexity and number of parameters. However, our evaluation showed that models more complex than the Nano version, despite having a significantly higher parameter count, did not provide appreciable improvements in detection accuracy. Therefore, we selected YOLOv8-Nano for our final implementation, as it offers the best trade-off between accuracy, speed, and resource usage.

The YOLOv8-Nano model, consisting of 3.2 million parameters, was trained on a high-performance server equipped with an NVIDIA A100 GPU (80 GB VRAM). The training set extends the dataset introduced in [

2] and recently used in [

10], with additional labeled images and object classes, including

person and

forklift, to better fit our scenario. The training was performed using five-fold cross-validation. The YOLOv8-Nano model is first converted to TensorFlow format, then quantized (using the TFLite format), and finally compiled for execution on the Edge TPU (

https://coral.ai/(accessed on 30 September 2025)). After quantization, the YOLOv8-Nano size is significantly reduced, with a final footprint of approximately 3.3 MB. Despite its reduced size and lower numerical precision (INT8), the quantized model maintains high detection accuracy, as shown in

Table 3. For model evaluation, we adopted the

metric (Intersection-over-Union threshold at 50%) for each class.

This deployment is both cost-effective (under $200 excluding the camera) and energy-efficient (consumption below 30 W under full load). The software stack is written in Python 3.10 and exposes results via a REST API for communication with the Aggregation Module.

To assess real-time performance, we conducted tests using three-minute video clips. After a 20-s warm-up phase, we measured the model’s inference time (i.e., the time required to process a single frame), the number of frames per second (FPS), and the

. Results are summarized in

Table 4.

The results confirm that YOLOv8-Nano enables efficient and accurate real-time video analysis, making it suitable for deployment in industrial safety scenarios.

3.3. Aggregation Module

The Aggregation Module serves as the central component of the safety monitoring system. It collects and integrates data from the Localization and AI modules to evaluate safety conditions in real-time. Its main responsibility is to enforce a predefined set of safety rules and, in case of violations or hazardous situations, trigger appropriate alerts (e.g., acoustic or visual signals) to notify workers in the area.

The module is implemented following a Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern, which ensures a modular and scalable structure. This design promotes ease of maintenance and facilitates the future addition of new rules or input sources. All internal and external communications occur through RESTful APIs, allowing loose coupling with the AI and Localization modules. Like the other components, the Aggregation Module runs on-premises entirely, preserving worker privacy and minimizing latency.

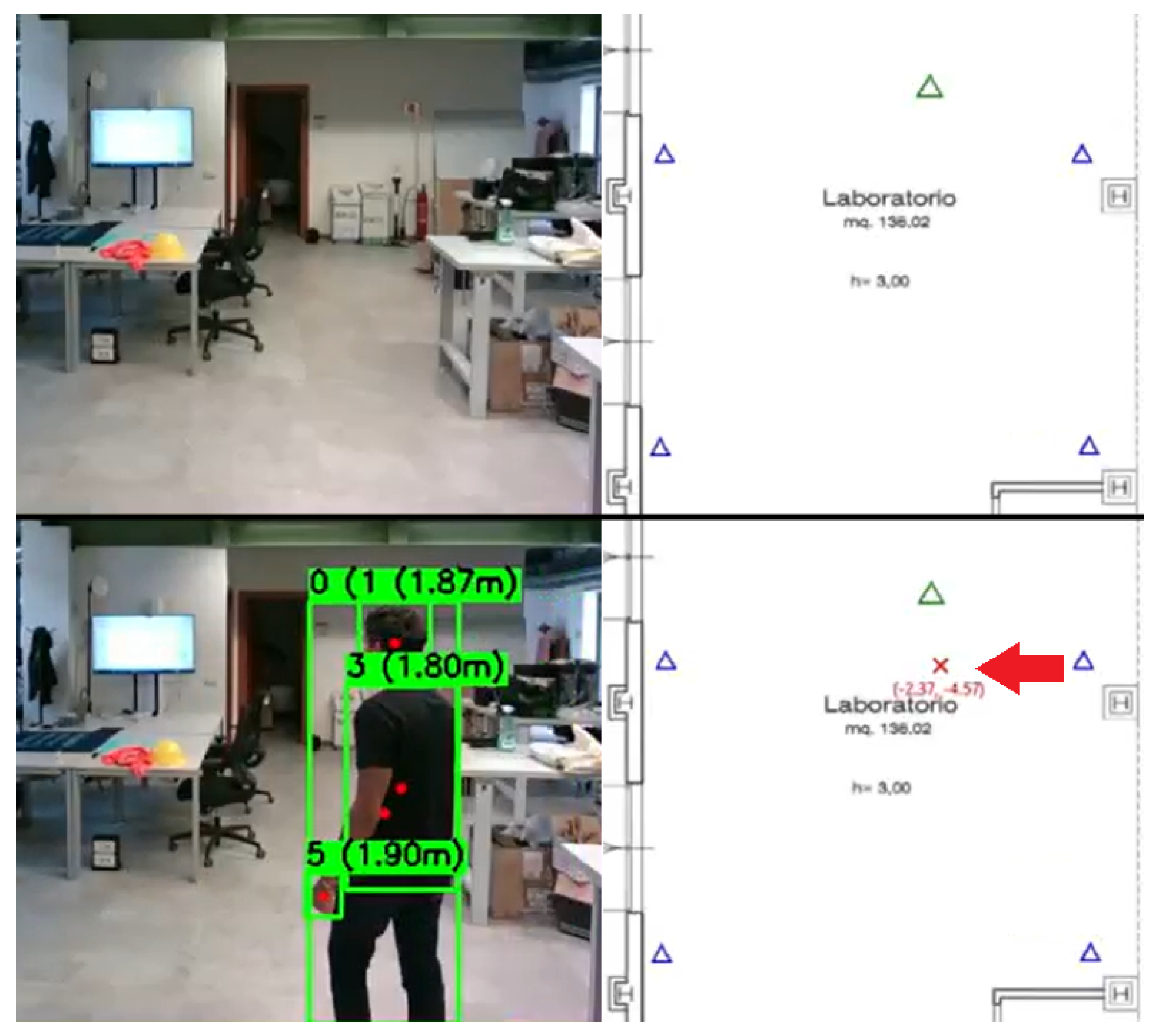

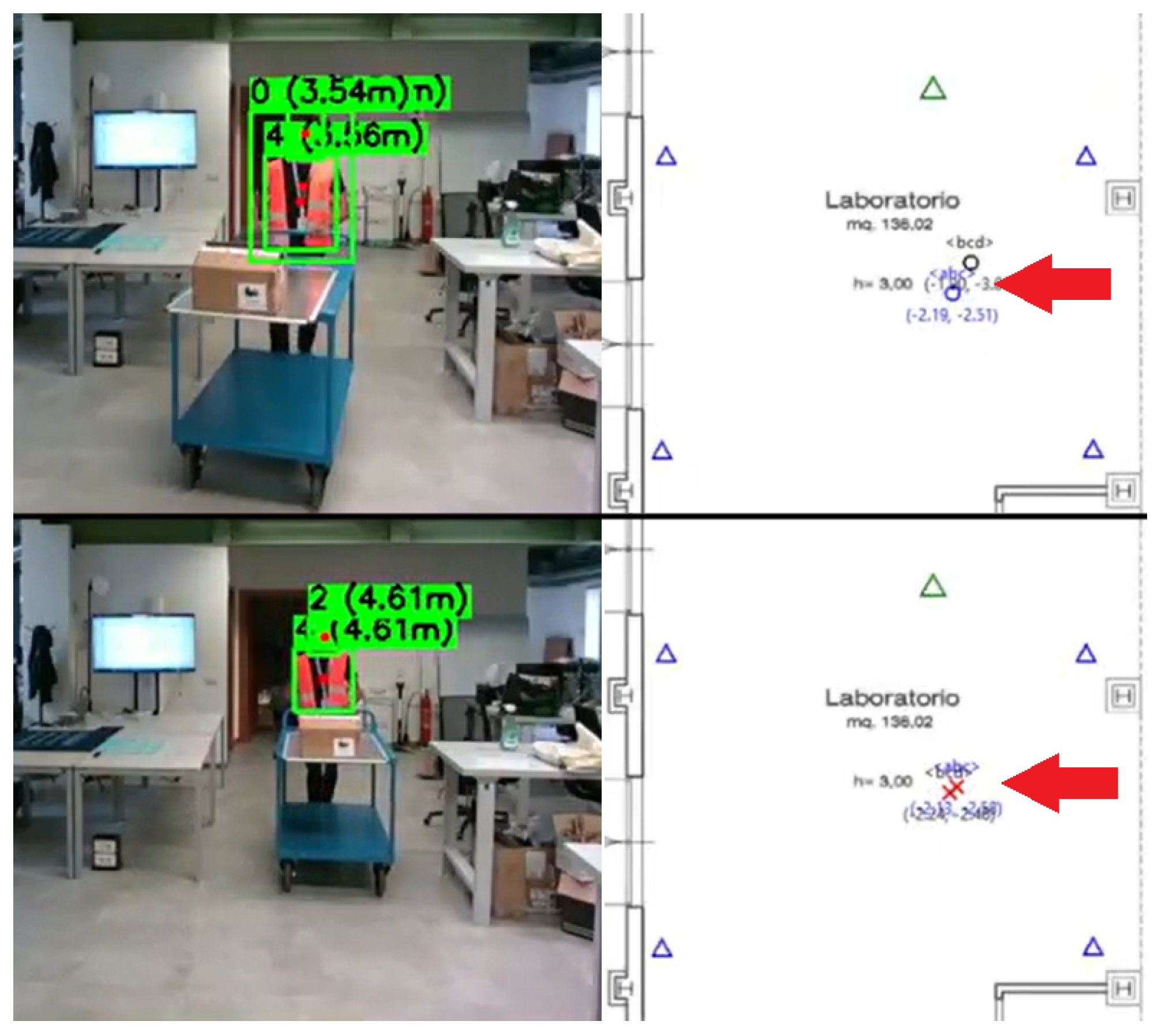

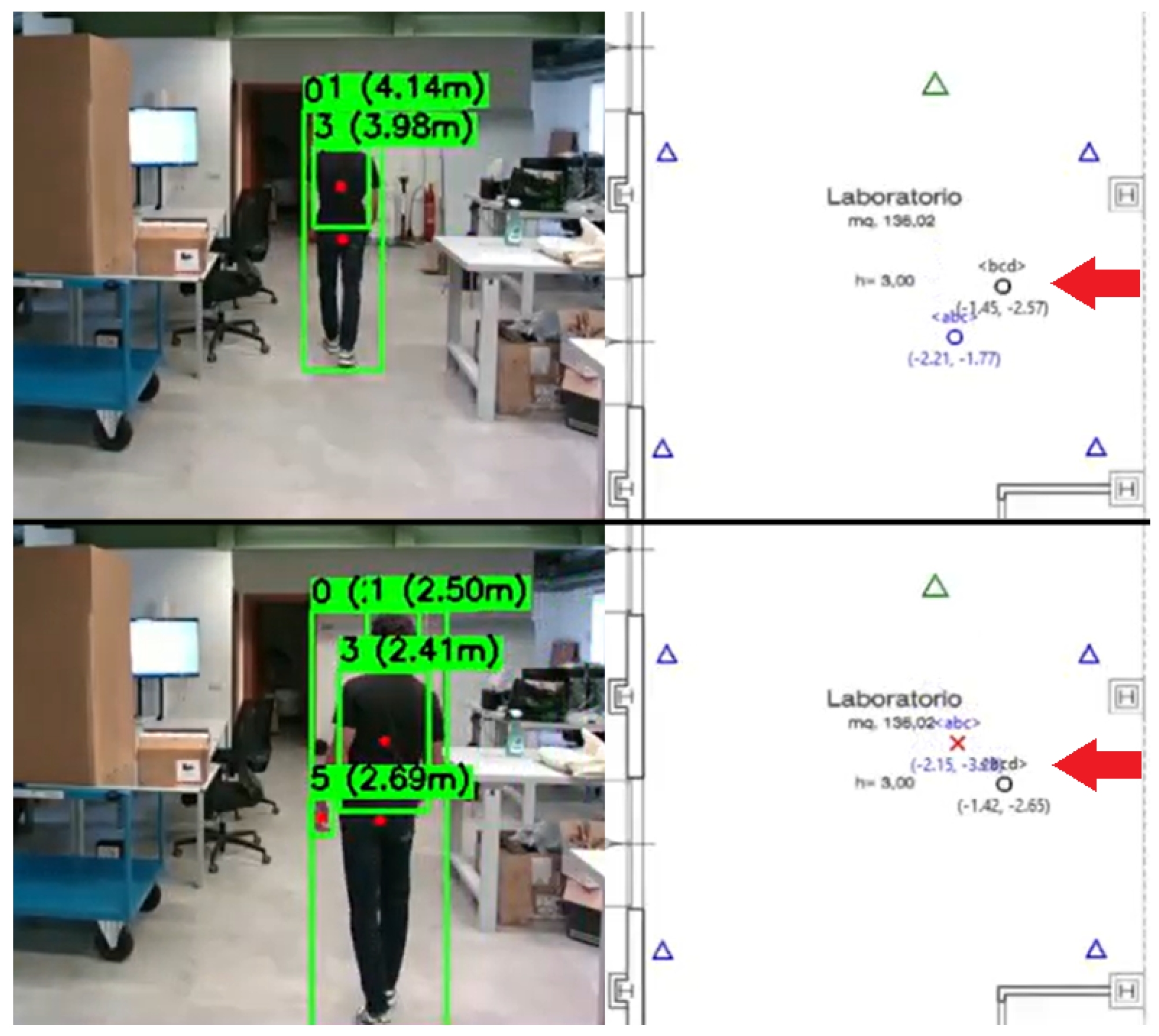

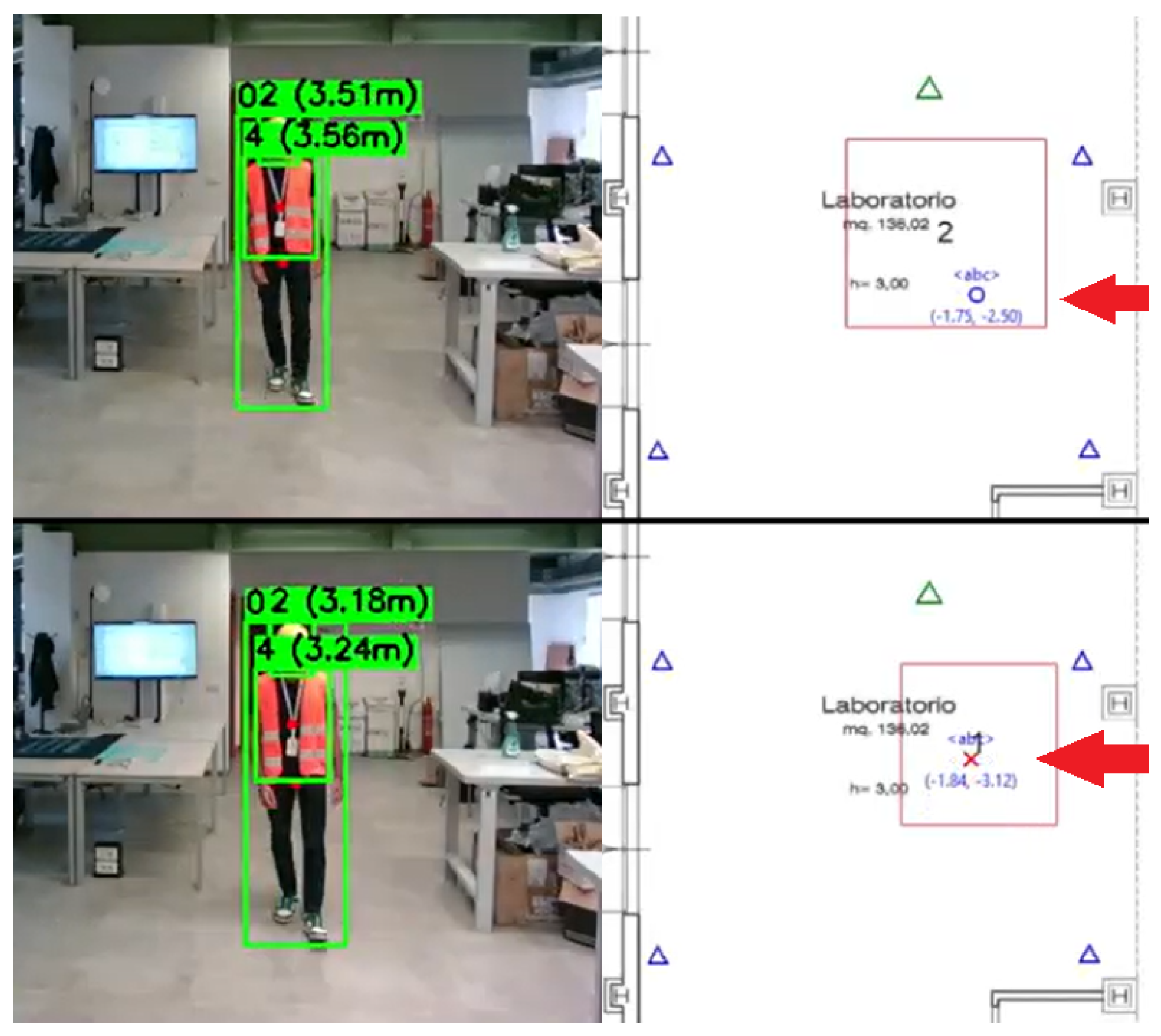

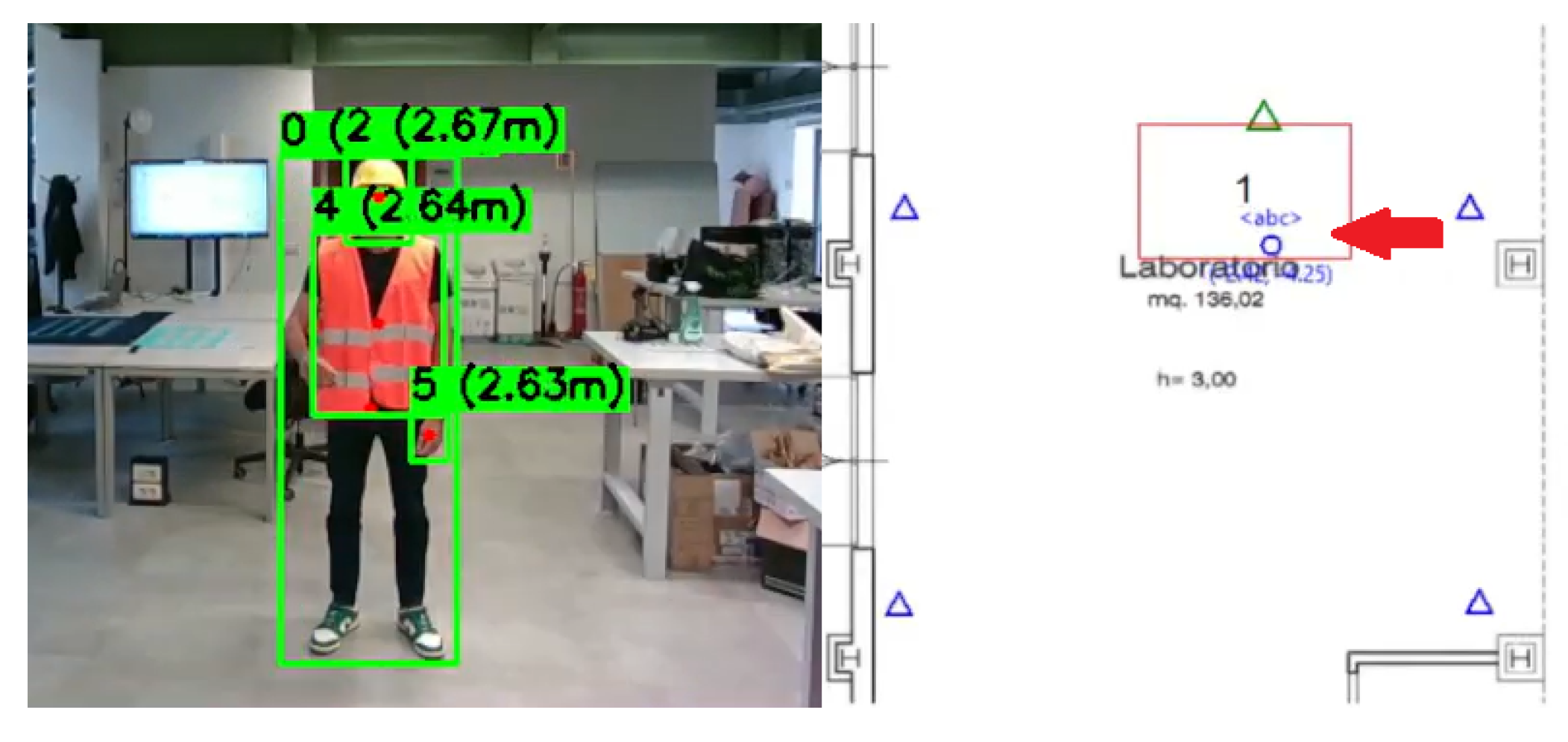

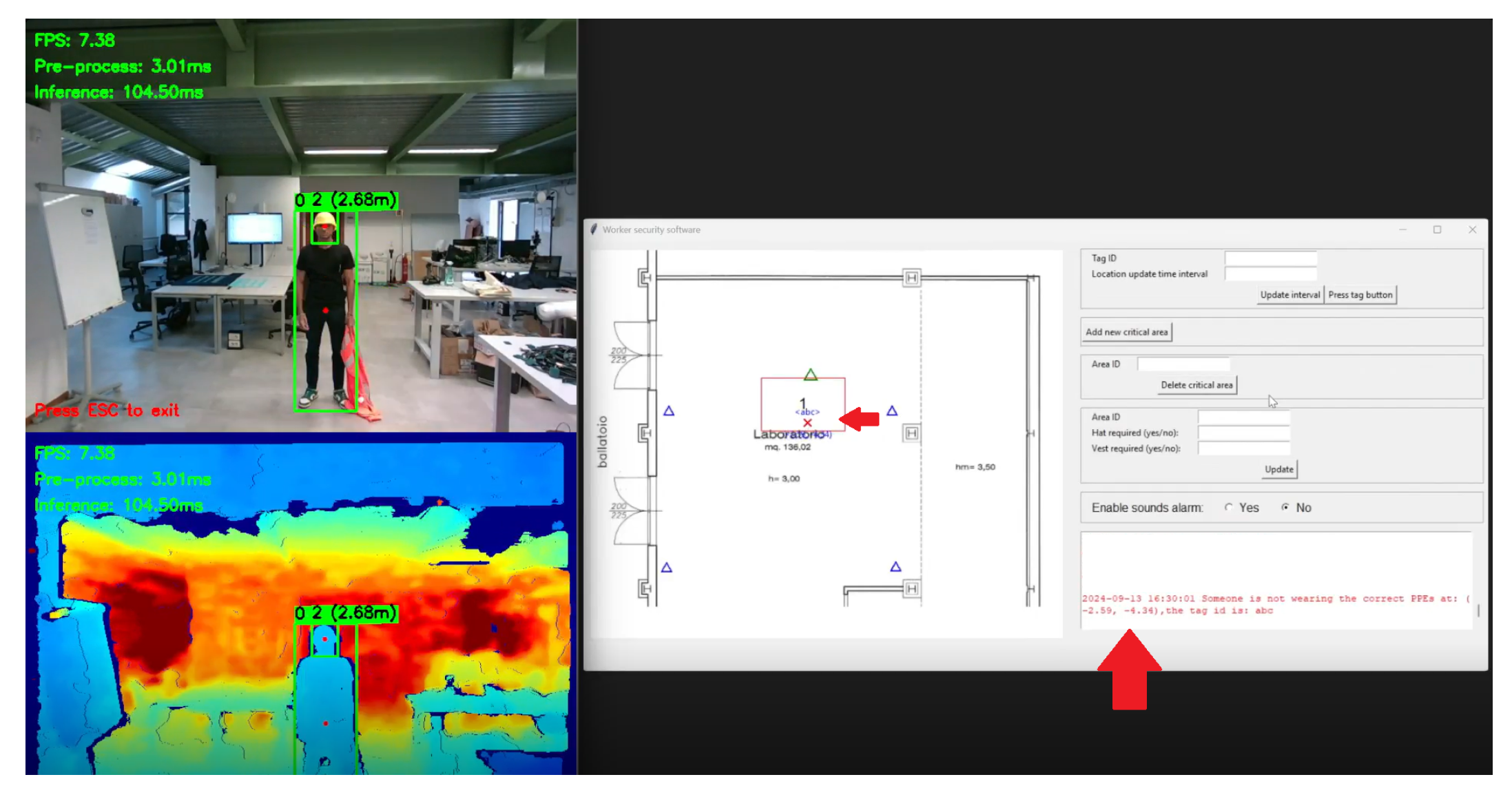

To enable real-time monitoring and system supervision, the Aggregation Module provides a comprehensive graphical user interface (GUI) that integrates multiple information streams into a unified dashboard (see

Figure 3). The interface serves three primary functions: (1) real-time visualization of both AI detections and RTLS tracking data, (2) immediate notification of safety rule violations through visual alerts and chronological event logs, and (3) interactive configuration of system parameters, including critical zone definitions, capacity limits, tag-to-person mappings, and authorization policies. This design allows safety operators to monitor the entire facility at a glance while maintaining full control over system behavior without requiring manual code modifications. Specifically, the interface includes:

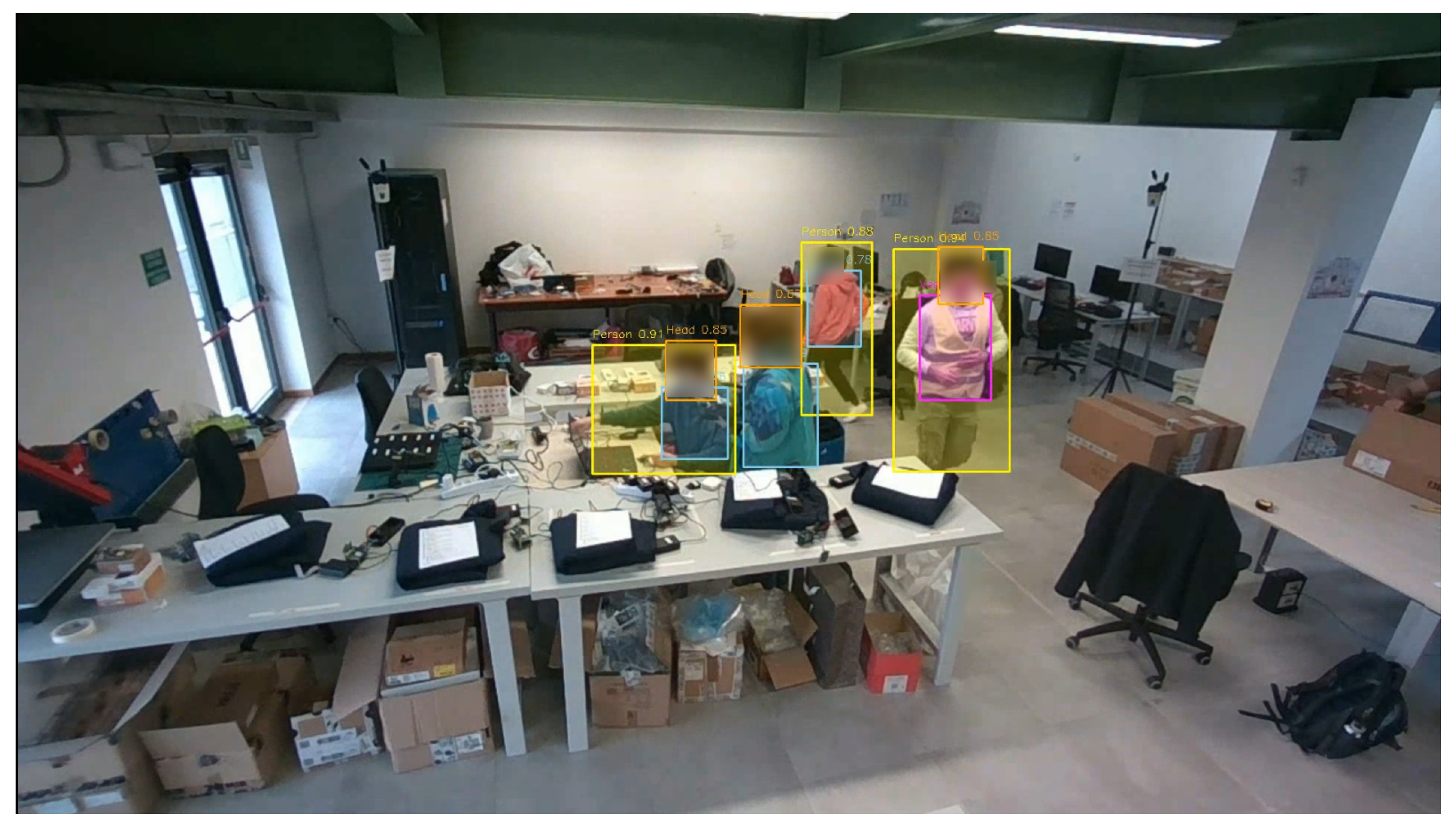

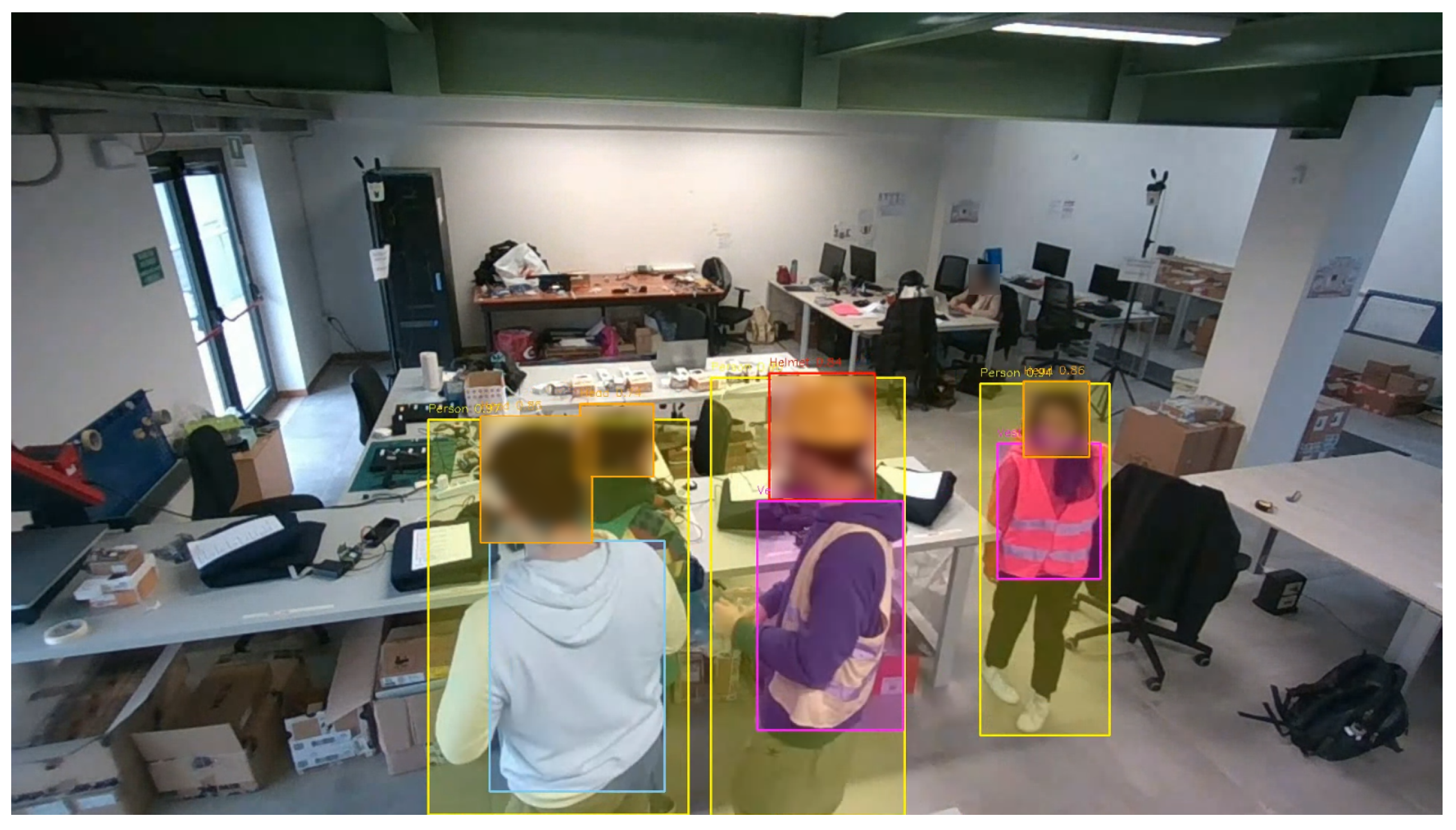

a live video stream from the cameras with object detection annotations (bounding boxes and class labels);

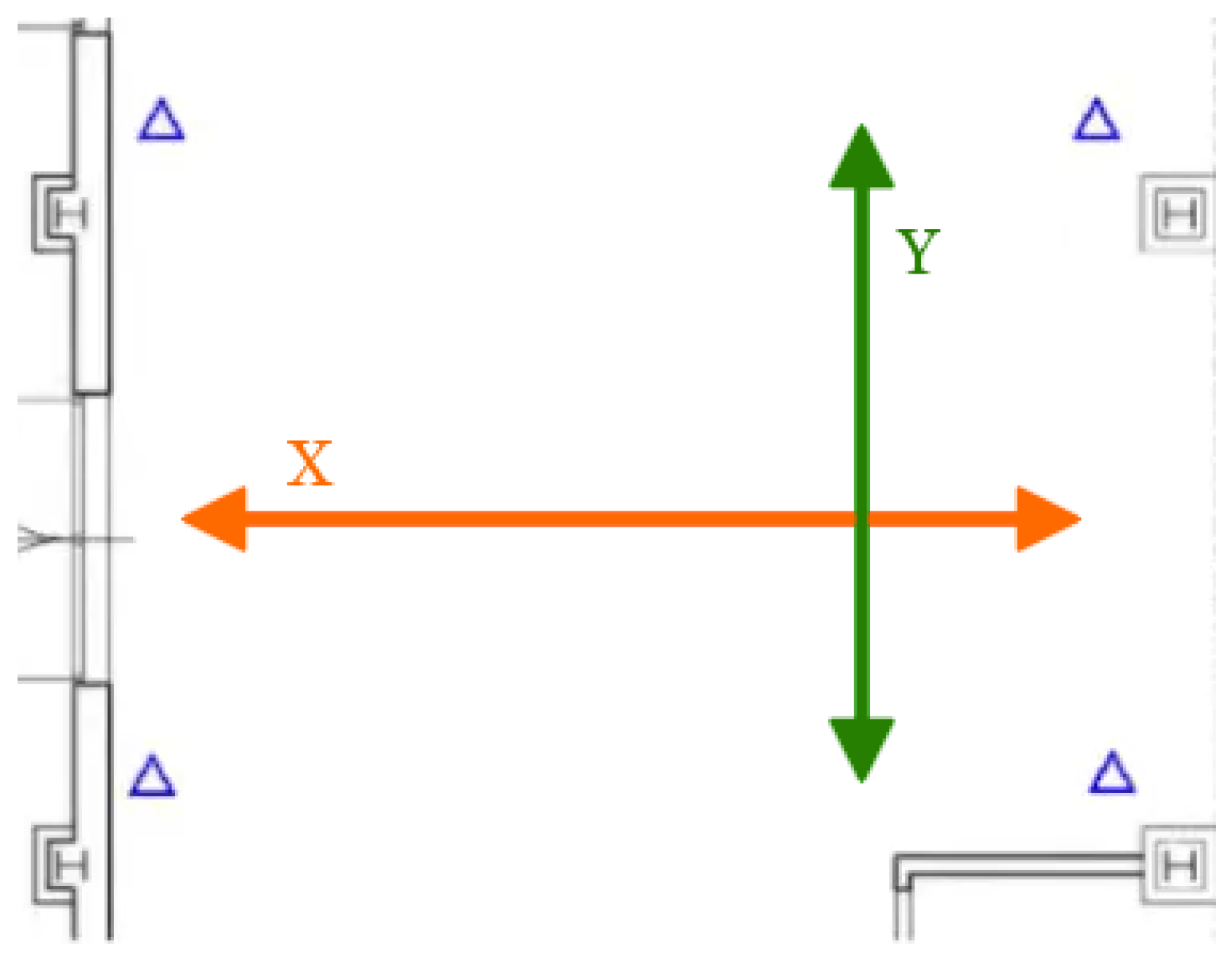

a 2D map of the monitored area showing the positions of UWB anchors, cameras, and tracked entities;

a dashboard displaying logs of rule violations, system messages, and visual alerts;

a configuration panel for setting critical zones, defining authorized personnel, updating tag associations, and managing other system settings.

The Aggregation Module receives:

From the Localization Module: a list of active tags, each with a unique ID, type (worker, visitor, or forklift), and real-time coordinates.

From the AI Module: a list of detected objects per video frame, including people, forklifts, and PPE items such as helmets and vests.

The data fusion process between the AI and Localization modules is implemented as a frame-synchronous event pipeline. Let

T denote the set of active RTLS tags and

D the set of objects detected in the current video frame

f. Each detected person

is characterized by an image-space centroid, computed as the center of the bounding box provided by the object detector. Using the camera calibration parameters (calculated at installation time), this centroid is projected onto the ground plane to obtain a world-space position

. Each RTLS tag

provides a real-time position

in the same world coordinate frame, together with metadata such as unique identifier, role, and authorization level. Associations between visual detections and RTLS tags are established through a nearest-neighbor matching procedure with spatial gating. A candidate pair

is considered admissible if the Euclidean distance between their projected positions does not exceed a confidence radius

r, defined as

with

, where

represents the typical localization uncertainty. Among all admissible pairs, this association minimizes the following spatial discrepancy function:

This discrepancy quantifies the geometric discrepancy between the world-space position inferred from the camera image and that provided by the RTLS system. The matching process thus selects the configuration that minimizes the overall spatial inconsistency between the two sensing modalities.

The centroid projection used to calculate the world-space position

is carried out as follows. For each bounding box detected by the AI module with class ID 0 (person) or 5 (forklift), the system computes the real-world position using camera calibration parameters configured during installation. Given a detected object centered at pixel coordinates

in an image with resolution

, the vertical angular offset

from the camera’s optical axis is computed using the camera’s vertical field of view

:

Using the distance

z from the camera to the detected object (obtained from depth information provided by the camera) and the angle

, the ground-plane distance

b is calculated as:

The horizontal angular offset

is then computed using the horizontal field of view

:

Finally, the coordinates

in the ground plane are obtained as:

These coordinates are expressed in the same reference frame used by the RTLS, enabling direct spatial comparison. Camera parameters, including position, orientation (in degrees), height, resolution, and field of view, are configured through the graphical interface during the initial system setup phase.

The computational complexity of this nearest-neighbor association is per frame, since each visual detection is compared with every active RTLS tag to evaluate the pairwise distance. Although more efficient data structures (e.g., k–d trees) could reduce this cost, the exhaustive formulation guarantees deterministic behavior and predictable real-time performance given the moderate number of entities typically involved. Detections or tags exceeding the gating threshold are treated as unmatched and are conservatively ignored to prevent false associations. Once the association step is completed, the Aggregation Engine evaluates the predefined rule set on the resulting tuples , enabling the system to reason over heterogeneous contextual information in real time.

The system architecture is implemented using a microservices design in which the three modules communicate via RESTful APIs using JSON-formatted messages. This design choice provides enhanced scalability, maintainability, and fault tolerance, allowing the Aggregation Module to continue operating even if one of the other modules becomes temporarily unavailable. To handle concurrent data streams efficiently, the module employs a multi-threaded processing pipeline with a pool of 20 worker threads instantiated at startup. When a new localization message arrives via the /aggregator/localization endpoint, a dedicated thread processes the tag position update. Similarly, when a detection message arrives via the /aggregator/detection endpoint, another thread handles the incoming frame data. This parallel processing strategy minimizes latency and ensures that the system can handle multiple simultaneous events without blocking.

The module maintains three primary data structures that are updated in real time as new information arrives. The objectList is a dynamically updated list representing the current state of all tracked entities, where each element contains information about a specific tag, including its current position, associated PPE status (if matched with a visual detection), zone membership, and authorization level. The viewerTable is a producer-consumer queue used to update the graphical user interface: when the data receiver server processes incoming information, it adds GUI update commands to this table, which are then consumed by a dedicated thread that renders the corresponding visual elements on the map display. The alarmList stores pending alarm notifications; when the rule evaluation logic detects a violation, it adds an alarm entry to this list, which is subsequently consumed and displayed in the log area of the graphical interface, optionally triggering a siren if configured.

Figure 3.

Graphical interface of the Aggregation Module showing the three main components of the system’s user interface. (a) Real-time camera feed panel with object detection annotations, displaying bounding boxes (red circles are the center) and class labels for detected workers, PPE items (helmet, vest), and forklifts. (b) 2D map panel showing UWB anchor positions (blue triangles), critical zones (red rectangles), the camera (green camera), an indication alert position (red arrow), and tracked entities. Visual markers indicate compliance status: blue circles represent compliant workers/vehicles, while red crosses highlight violations. (c) Dashboard panel displaying chronological rule violation logs with timestamps and rule IDs, system status messages, and a configuration panel for defining critical zones, setting capacity limits, managing tag-to-person associations, and configuring authorization policies.

Figure 3.

Graphical interface of the Aggregation Module showing the three main components of the system’s user interface. (a) Real-time camera feed panel with object detection annotations, displaying bounding boxes (red circles are the center) and class labels for detected workers, PPE items (helmet, vest), and forklifts. (b) 2D map panel showing UWB anchor positions (blue triangles), critical zones (red rectangles), the camera (green camera), an indication alert position (red arrow), and tracked entities. Visual markers indicate compliance status: blue circles represent compliant workers/vehicles, while red crosses highlight violations. (c) Dashboard panel displaying chronological rule violation logs with timestamps and rule IDs, system status messages, and a configuration panel for defining critical zones, setting capacity limits, managing tag-to-person associations, and configuring authorization policies.

The system’s operational performance depends on several configurable parameters and environmental factors validated through laboratory and field tests.

Table 5 summarizes the key parameters and their validated operational ranges. The association radius

r is set as

with

, resulting in a threshold of approximately 0.7 m. Camera height was validated across a range of 2.0 to 5.0 m with tilt angles between

and

. The qualitative validation identified that detection accuracy degrades significantly beyond approximately 8 m from the camera, where individuals may not be reliably identified by the AI module. Additionally, objects positioned at image boundaries or heavily occluded by other entities may be missed by the detection algorithm. These limitations are inherent to vision-based systems and highlight scenarios where the RTLS provides critical redundancy. The proximity threshold for collision detection (Rule 6) is configurable and was set to 1.0 m during validation.

To maintain partial functionality in case of component failure, the Aggregation Module implements a fault tolerance mechanism through two dedicated monitoring threads that continuously verify the operational status of the AI and Localization modules. Each monitoring thread checks every 10 s whether the corresponding module has sent data within a configurable timeout period by tracking the elapsed time since the last received message. If the timeout threshold is exceeded, the module is declared unavailable, and the system transitions to a degraded operational mode with relaxed safety constraints. When the Localization Module is unavailable, the system can still enforce Rules 2 and 3, which rely primarily on visual detection data. Conversely, when the AI Module is unavailable, the system continues to enforce Rules 4, 5, 6, and 7, which depend primarily on localization data. Rule 1, which requires both PPE detection and zone membership verification, becomes unavailable when either module fails. During degraded operation, the monitoring thread responsible for the failed module periodically attempts to re-establish the connection every 10 s, and once the connection is successfully restored, the system automatically returns to full operational mode, re-enabling all seven safety rules.

By correlating this data, the module can identify mismatches between detected persons and registered tags (e.g., an unidentified person not wearing a tag), and verify PPE compliance based on location and context (e.g., presence in a critical zone).

The Aggregation Module evaluates a set of safety rules designed to prevent unauthorized access, ensure PPE usage, regulate forklift operations, and monitor proximity conditions. Some rules rely on the fusion of heterogeneous data sources (e.g., combining visual and localization data), while others use data redundancy to ensure robustness in case of partial system failure.

The following rules have been defined in order to showcase the potential of the proposed data fusion approach:

Rule 1 (R1): An alarm is triggered if a person is detected in a critical area without wearing the required PPE (e.g., helmet or vest).

Rule 2 (R2): An alarm is triggered if an unidentified person (i.e., not associated with any tag) is detected.

Rule 3 (R3): An alarm is triggered if a forklift is detected by the AI module but not tracked by the RTLS.

Rule 4 (R4): An alarm is triggered if a forklift is in operation without an authorized driver nearby.

Rule 5 (R5): An alarm is triggered if the number of individuals in a critical area exceeds the predefined limit.

Rule 6 (R6): An alarm is triggered if the distance between a worker and a forklift drops below a minimum safety threshold and continues to decrease.

Rule 7 (R7): An alarm is triggered if a person enters a restricted area where they are not authorized.

In order to analyze the enforcement of each rule with different configurations,

Table 6 analyzes the five core features provided by three different deployment strategies: AI-only, i.e., a system relying only on computer vision, RTLS-only, i.e., a system relying only on UWB localization, and the proposed approach, i.e., a system that relies on the fusion of the data from the AI and the RTLS systems. The table shows clearly that the proposed approach is the only one providing all the features.

If we analyze the features provided by the AI PPE detector and the RTLS, we can notice that the two technologies offer complementary characteristics, as the AI module excels at visual analysis, while the RTLS provides accurate identification and localization. However, neither system in isolation provides all the features. More specifically, the AI-only system provides accurate PPE detection and can visually recognize a person’s presence, but it cannot determine their identity, such as whether the worker is authorized or not. This limitation is addressed by the RTLS, which assigns each worker a unique, pre-configured tag, enabling reliable identification of the person. Similarly, when it comes to tracking, the AI module can only track people or vehicles within its field of view, making its tracking capability inherently partial and dependent on camera positioning. In contrast, RTLS offers comprehensive site-wide tracking, providing continuous updates even in non-visible areas. The same reasoning applies to vehicle tracking, where AI-only solutions may not work due to occlusions or limited viewpoints, whereas RTLS ensures consistent tracking across the entire environment. Finally, when it comes to people counting, the AI system outperforms RTLS because it can detect all visible individuals, including visitors or untagged personnel. RTLS, on the other hand, can only count people wearing an active tag, making its counting capability only partial.

Based on these features in

Table 7, we analyze the feature requirements of each safety rule, showing that many rules depend on multiple complementary features, which cannot be provided by the AI PPE detector or the RTLS only. In the following, we analyze the requirements for each rule.

Rule 1 requires a combination of PPE detection and person tracking. A visual system can fairly determine whether a worker is equipped with the required PPE, however, it cannot accurately determine the worker’s position relative to the entire surface served by the system. The RTLS system, on the other hand, offers precise localization but cannot perform visual assessments. Their integration allows for verification of PPE compliance within critical areas.

Rule 2 requires the availability of person identification and tracking. The RTLS system assigns each tag to a specific individual, thus enabling reliable identification, however, it cannot detect untagged individuals. The AI module, on the other hand, detects all visible individuals, including visitors or unauthorized personnel, but does not provide identity information. By correlating visual detections with RTLS tag data, the integrated system identifies discrepancies between detected individuals and registered tags, thus enabling the detection of untagged or unexpected individuals within the monitored environment.

Rule 3 requires vehicle tracking from both sources. AI-based detection identifies any visible vehicle, including unregistered or unexpected ones, however, it remains prone to inaccuracies due to occlusions and camera coverage limitations. RTLS ensures continuous tracking of tagged vehicles, however, it cannot detect untagged forklifts. Data fusion enables cross-validation of vehicle detections, thus ensuring the identification of missing tags and reducing false alarms.

Rule 4 relies on people and vehicle tracking, along with the ability to associate drivers with specific vehicles. AI can classify people and vehicles; however, it cannot determine their identity. RTLS provides identity information and tracks both workers and vehicles; however, it cannot assign semantic labels. Merging the two streams of information allows for the verification that a forklift is operated by an authorized worker associated with the corresponding RTLS tag.

Rule 5 requires the counting and tracking of people. The AI-based configuration is capable of counting all visible individuals, regardless of whether they are wearing a tag. On the other hand, RTLS provides accurate zone membership, however, it can only count tagged personnel. Their combination enables accurate and comprehensive monitoring in specific areas, thus ensuring compliance with capacity limits under realistic conditions.

Rule 6 relies on tracking people and vehicles, with a focus on precision. The AI-only system provides PARTIAL tracking because image-based distance estimation is affected by perspective distortions, occlusions, and a lack of depth information. RTLS provides accurate three-dimensional distance measurement; however, it does not distinguish between workers and vehicles. The combined system can ensure the accuracy of RTLS with the semantic classification of the AI system, thus enabling robust proximity assessment and preventing both false positives (e.g., proximity events involving non-human objects) and false negatives (e.g., occluded workers remaining tracked via RTLS).

Rule 7 requires the identification and tracking of individuals. RTLS provides identity and authorization; however, it cannot detect untagged individuals. AI detects all the individuals, but it cannot determine their identity. The integrated system links visual detections to RTLS tag data, ensuring that only authorized and properly identified personnel access restricted areas, while also enabling the detection of unauthorized or untagged access.

In the following section, we present experimental validation that demonstrates how the proposed system successfully enforces all seven rules in realistic scenarios.