1. Introduction

The application of Wireless Vital Parameter Continuous Monitoring (WVPCM) in healthcare has emerged as a transformative technology to manage patients with different pathologies and hospitalization stages. Wireless and wearable biosensors allow continuous monitoring of physiological and biochemical factors with real-time transmission of patient data to integrated systems. Recent advancements in materials, micro-technologies, and wireless connections have significantly improved the accessibility and functionality of biosensors [

1].

In hospitalization settings, patients normally receive manual checks from nurses every 4–6 h on average, which may leave extended periods of subtle changes undetected. These changes can culminate in Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) that significantly worsen the patient’s health status [

2]. The introduction of WVPCM technologies can influence both the sensing and response stages of monitoring and can enable an earlier recognition of significant changes in vital signs [

3]. Numerous studies confirm the efficacy of WVPCMs in different contexts. WVPCM devices appear to be especially beneficial in general wards, where care-intensity is normally low [

4]. Evidence shows that continuous monitoring in these wards enhances the timeliness of rapid responses and reduces the risk of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions [

5]. In some instances, continuous monitoring ultimately contributes to the reduction in mortality rates for general ward patients [

6]. Three studies [

2,

7,

8] concentrate on patients recovering from major abdominal surgery associated with oncological pathologies. Major abdominal surgery is frequently subject to post-operative complications; hence, the prompt recognition of adverse events is essential. Continuous monitoring is proven to identify signs of complications hours before manual monitoring, with the potential of implementing earlier treatments to patients. Additional research confirms the efficacy of continuous monitoring technology in surgical ward contexts. Weller et al. (2024) [

9] demonstrate that wearable devices allow early detection of negative clinical outcomes in a sample of 11,977 patients over a fifteen-month period in the medical surgical departments of two hospitals. Van Rossum et al. (2023) [

10] confirm that WVPCM devices benefit from higher alarm sensitivity as compared to manual monitoring, and consequently contribute to an earlier detection of potential complications. Continuous monitored patients also display a lower probability of being admitted to the ICU and ultimately lower mortality rates compared to those who received manual intermittent monitoring, as observed on a sample of 34,693 patients in post-surgical units [

11]. To conclude, a continuous monitoring system was applied to Heart Failure (HF)-hospitalized patients in Japan. The system improved patient self-management and supported rapid clinical intervention [

12].

Academic research confirms that WVPCM devices are not only effective in patient monitoring but also improve working conditions for healthcare professionals. These devices help streamline the workload of nurses in terms of patient management and decrease their perception of stress and anxiety associated with unexpected deterioration of patient conditions [

8]. Nurses confirmed in a series of in-depth interviews that the monitoring devices gave rise to feelings of safety and care in their daily working routines [

13].

Although the advantages of employing WVPCM in different hospital settings are well-documented, its clear and widely accepted impact on patient conditions still requires rigorous investigation [

14]. It is also clear that these monitoring devices are positively perceived and help reduce the workload for healthcare professionals. However, their cost-effectiveness for healthcare organizations must be fully demonstrated. WVPCM devices come with inherent initial hardware costs and additional maintenance expenses for daily operation. Healthcare professionals must be properly trained and are required to support patients using these devices [

15]. Technical difficulties also emerge in their implementation because in some cases, there is a lack of consistency between the monitoring data flow and the hospital data systems [

16]. Healthcare professionals must also manage issues such as missing connectivity and limited battery life [

17]. Furthermore, nurses can be exposed to alarm fatigue, because WVPCM devices can significantly increase patient support requests. A standardized level of alarm is difficult to set given the diverse patient conditions [

18].

There is indeed a lack of research focused on IM settings, despite the fact that they present unique challenges and complications where these devices could offer significant value and utility. Patients in IM units often experience acute conditions of varying severity and often require intensive care because of ongoing epidemiological transitions [

19]. These patients are frequently not stratified according to co-morbidities, dependency level, disease severity, and clinical complexity, and nurses generally monitor these patients on an intermittent basis. In addition, there is no proper risk assessment for rapid clinical deterioration, which can result in sub-optimal treatment, extended hospital stays, and increased healthcare costs [

20]. While earlier research concentrated on surgical or high-dependency wards with relatively uniform patient conditions and monitoring needs, the specific features of Internal Medicine patients can influence the integration of monitoring technologies. The LIMS offers new insights into how WVPCM can be deployed in this complex hospital setting, evaluating its clinical relevance, effects on workflow, and perceived value by healthcare professionals. Although no formal economic analysis was conducted, indirect indicators contribute to an initial understanding of its potential organizational benefits. This focus expands the current evidence and supports a more appropriate evaluation of WVPCM adaptation to various hospital environments beyond surgical care.

Thus, the aim of this study is to assess whether the use of WVPCM improves clinical outcomes, such as major complications, deaths, and length of stay, in critically ill patients hospitalized in Internal Medicine wards. An investigation of the attitude of nurses towards the use of new technologies in daily practice to improve patient management was also carried out.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

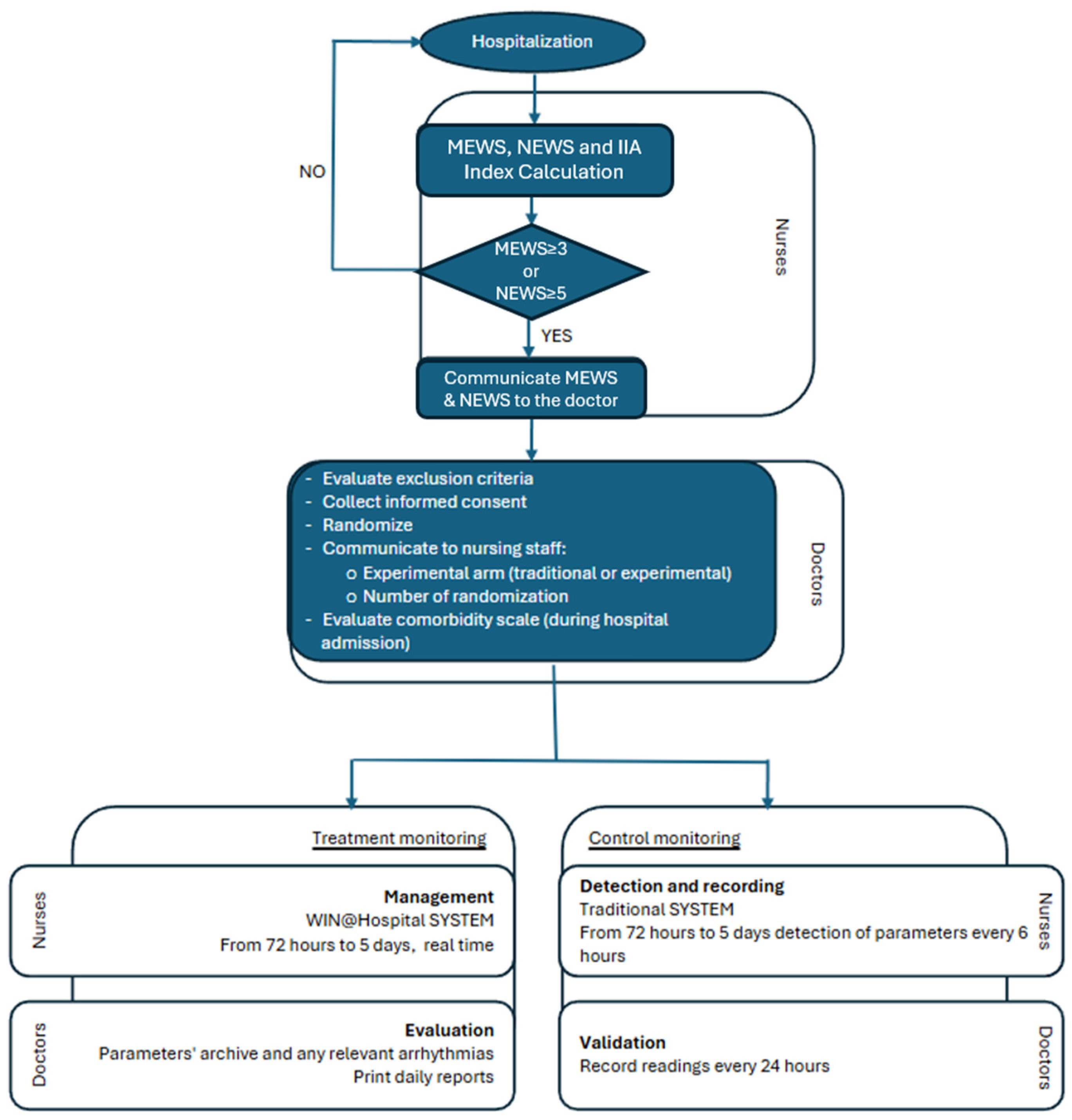

The LIght Monitor Study (LIMS) is a prospective, open-label, randomized, multi-center pilot trial designed to compare wireless vital sign monitoring to standard monitoring in critically ill patients during hospitalization. An independent unit at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia carried out centralized randomization. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive WVPCM or standard monitoring according to a 1:1 computer-generated scheme. The randomization was web-based and only the independent website administrator knew the randomization sequence. Once randomized patients were monitored continuously during the first 72 h, with the possibility of extending observation to 120 h, with Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) ≥ 3 and/or the National Early Warming Score (NEWS) ≥ 5 after the initial 72 h (

Figure 1) [

21,

22]. Patient monitoring primarily focuses on two aspects: (1) the monitoring of vital parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, posture, and electrocardiogram (ECG), and (2) the activation of alerts when the measured parameters fall below threshold values set at the start of monitoring or if abnormalities are detected on the ECG.

To evaluate how nurses respond to the use of new technologies in daily practice for improved patient management, a qualitative study was conducted in parallel. The survey specifically targeted the medical staff who utilized the new wireless monitoring system, with the objective of investigating their impressions and evaluating its impact on clinical practices. The questionnaire consisted of eight questions designed to assess the level of satisfaction with the adoption of software-based management tools and electronic medical devices in patient care. The questionnaire was administered via the Qualtrics platform, allowing participants to share their impressions voluntarily and anonymously.

This study extends the preliminary findings reported by Pietrantonio et al. (2019) [

22]. Compared to the previous study, which was based on 95 patients, this one extended the number of centers from one to two and increased the number of patients involved in the trial. The size of the study is therefore larger, and the results are interpreted in light of recent developments in the literature on WVPCM devices. This study included two Internal Medicine (IM) hospital units. The first unit, part of the Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale (ASST) Garda at Manerbio Hospital (Brescia, Italy), participated in the initial phase of the study. The second unit belongs to the Azienda Sanitaria Locale (ASL) 6 at Castelli Hospital (Ariccia, Rome, Italy). The examination of Emergency Room (ER) operational activities in both ASST Garda and ASL 6 discloses a serious growth in ER visits with subsequent admission to Internal Medicine (IM) wards in patients over 65 years old with no seasonal variations [

22].

These units are consistent with the general characteristics of IM settings described above. Patients often present with acute conditions of varying severity [

11], are not effectively differentiated on clinical conditions, and lack proper risk assessment for rapid deterioration [

20].

The study design was supported by evidence from previous studies, such as an interventional study conducted in order to integrate clinical data from acute and critically ill patients with economic cost analyses of inpatient management in IM wards [

23], and a study evaluating the efficacy of a wireless continuous monitoring system in reducing major complications, improving patient outcomes and quality of care, and reducing costs compared to conventional monitoring performed by nurses at scheduled intervals [

24,

25].

The intervention specifically targets the first 72 h of hospitalization, which is a critical window for detecting early deterioration. Furthermore, cost-saving potential is assessed indirectly by analyzing reductions in average Length of Stay (LOS) and reductions in major complications as proxy indicators.

Continuous vital sign monitoring can facilitate early detection of deterioration in acute patients in a general, non-intensive care setting, such as the Internal Medicine Unit. This allows healthcare professionals to promptly respond to changes in the patient’s condition and implement appropriate treatments.

2.2. Presentation of Design

Comparison of wireless monitoring and conventional monitoring in the first 72 h of hospitalization, for unstable patients with MEWS ≥ 3 and/or NEWS ≥ 5, was carried out by using a randomized controlled trial.

Experimental group: Patients with MEWS greater than or equal to 3 and/or NEWS greater than or equal to 5 on admission, regardless of the reason for hospitalization, together with all patients with poor glycemic control and/or severe fluid and electrolyte imbalance, regardless of MEWS/NEWS, who are all considered eligible for continuous wireless monitoring using the WIN@Hospital system [

26].

Control group: Patients with MEWS greater than or equal to 3 and/or NEWS greater than or equal to 5, on admission, regardless of the reason, and all patients with poor glycemic control and/or severe fluid and electrolyte imbalance, regardless of MEWS/NEWS, who continued to undergo traditional monitoring performed at regular intervals (at least 4 times a day) by the nursing staff.

2.3. Study Population

All critical patients (with the need for continuous high technology monitoring) without a pacemaker, with MEWS ≥ 3 and/or NEWS ≥ 5 on admission, and all patients with glycemic decompensation and/or severe fluid and electrolyte imbalance, regardless of MEWS/NEWS [

22,

27].

2.4. Identification of the Monitoring Tool

The WIN@Hospital system is a portable wireless system (Medical Class IIA) performing continuous, instantaneous vital sign monitoring, and automatic calculation of the NEWS, with the creation of a personalized alert system for each patient via a portable device (iPad), reducing the need for the constant presence of nursing staff [

26].

The continuous monitoring carried out by the SYSTEM WIN@Hospital is automatically added to the Electronic Health record (EHR) (Tabula Clinica WebAppVers.1) by Dedalus Healthcare Systems Group) utilized by the Internal Medicine Unit and allows continuous supervision of patients’ vital parameters, ECG, and NEWS 24 h a day.

Monitoring Device: Safety Assessment

The WIN@Hospital system is a portable, wireless Medical Class II device system designed for continuous, real-time monitoring of patients’ vital signs. It automatically calculates the NEWS and generates personalized alerts for each patient, all accessible via a portable device, contributing to the reduction in constant supervision by nursing staff. As a Class IIA device, it is not designed for intensive monitoring or life-saving purposes. It serves as a supportive tool for tracking clinical parameters, assisting in diagnostic processes, automating data collection, and reducing clinical risks.

The study was approved by the Provincial Ethics Committee of the Province of Brescia with number NP 2659 and by the Lazio 2 Ethics Committee with number S 28.18.

The study was registered at Clinical trials Gov with number NCT 03050034.

2.5. Included Patients

The study compares wireless monitoring vs. conventional monitoring during the first 72 h of hospitalization, for unstable critically ill patients with MEWS ≥ 3 and/or NEWS ≥ 5 [

6]. The study flowchart is represented in

Figure 2.

2.6. Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study is the occurrence of major complications, defined as at least one of the following events, whichever occurred first: repeated hospital readmission, readmission within 21 days after discharge, sudden death, healthcare-associated infection, arrhythmia, acute coronary syndrome, respiratory failure, or glycemic decompensation. Secondary endpoints included in-hospital mortality, end-stage disease, discharge home, length of hospital stay, and the time spent by nurses on vital signs monitoring.

Throughout this study, the definition of possible complications is the same as the definition used for Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), from the National Library of Medicine (NLM)-controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles for PubMed: “Conditions or pathological processes associated with the disease” [

28]. Similarly, the same definition of death was considered: “Irreversible cessation of all bodily functions, manifested by absence of spontaneous breathing and total loss of cardiovascular and cerebral functions” [

27].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical Methodology

The sample size was determined according to the primary outcome of the study, which is major complications. Data from previous studies suggested that at least 15% of critically ill patients hospitalized in Internal Medicine units would experience major complications.

Therefore, we considered a decrease in the risk from 15% to 5% in the experimental arm to be clinically significant. By setting error α and β equal to 5% and 20%, or 80% power, recruitment of 141 patients per arm would be necessary to detect a statistically significant absolute difference of at least 10%. Taking into account an estimated 5% drop-out rate, we increased the sample size to 148 patients per arm (296 patients in total).

With regards to data analysis, descriptive statistics (mean, median, and related distribution parameters) were reported for continuous variables, while the absolute frequencies, relative and percentage, were calculated for differing categorical variables. Measures of association, such as the difference between risks (DR) and hazard ratio (HR), were used to assess binary and time-to-event outcomes, while the differences between means and medians were considered for continuous variables. Each point estimate was reported with a corresponding 95% confidence interval. All analyses were conducted by using STATA version 18.

3. Results

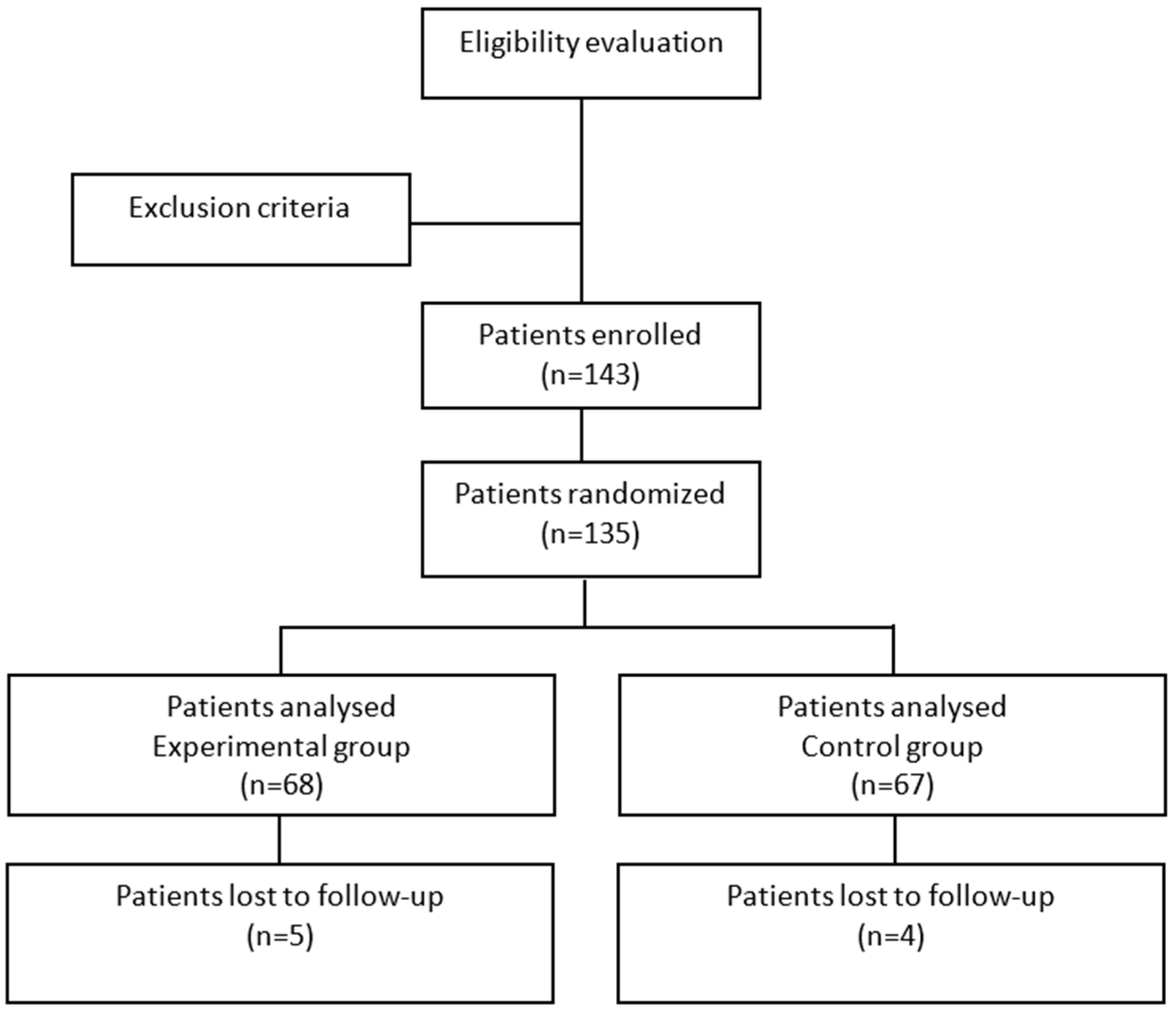

Although the study planned to enroll a total of 296 patients, due to the COVID outbreak, it was interrupted in advance when only 135 patients (WVPCM = 68; standard care = 67) were randomized. This reduction in sample size decreased the study’s power from 80% to 52%. The experimental group enrolled 68 patients, while the control group enrolled 67 patients. The baseline characteristics of the two groups are summarized in

Table 1, while the study design is shown in

Figure 3.

Patients in the experimental and control groups did not differ in terms of main prognostic factors. The average age was 79.6 years in the control group compared to 77.3 years in the experimental group. The gender distribution was similar between the two groups, with a balanced male-to-female ratio (28/66 in the control group vs. 22/68 in the experimental group). The average Body Mass Index (BMI) was 26.6 in the control group and 28.1 in the experimental group. The comorbidity burden, measured by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Comorbidity Index (CIRS-CI), was comparable between groups, with scores of 3.68 in the control arm vs. 3.75 in the experimental arm. The percentage of patients who had ≥4 comorbidities was comparable (53.7% vs. 46.9%), while the severity index (CIRS-SI) was also similar (1.84 vs. 1.82). The Nursing Intensity Index (IIA) scores [

18] were closely matched between groups, with the experimental group showing an average score of 3.28 compared to 3.14 in the control group. In addition, similar percentages of patients in the experimental and control groups fell into the higher-risk IIA category (3–4), accounting for 58/68 and 60/66, respectively. The BRASS index, which is employed to assess discharge planning complexity, was comparable between groups (15.30 vs. 16.8), as well as the percentage of patients in the control and experimental group with BRASS scores of 20 or above (35.9% vs. 43.8%). The distribution of Diagnostic Related Groups (DRGs) was consistent across both groups, with respiratory failure (DRGs 087–088), heart failure (DRG 127), and sepsis (DRG 576) being the most common diagnoses. The major diagnostic categories (MDCs) were also similar, predominantly involving respiratory (MDC 4), cardiovascular (MDC 5), and infectious (MDC 18) diseases.

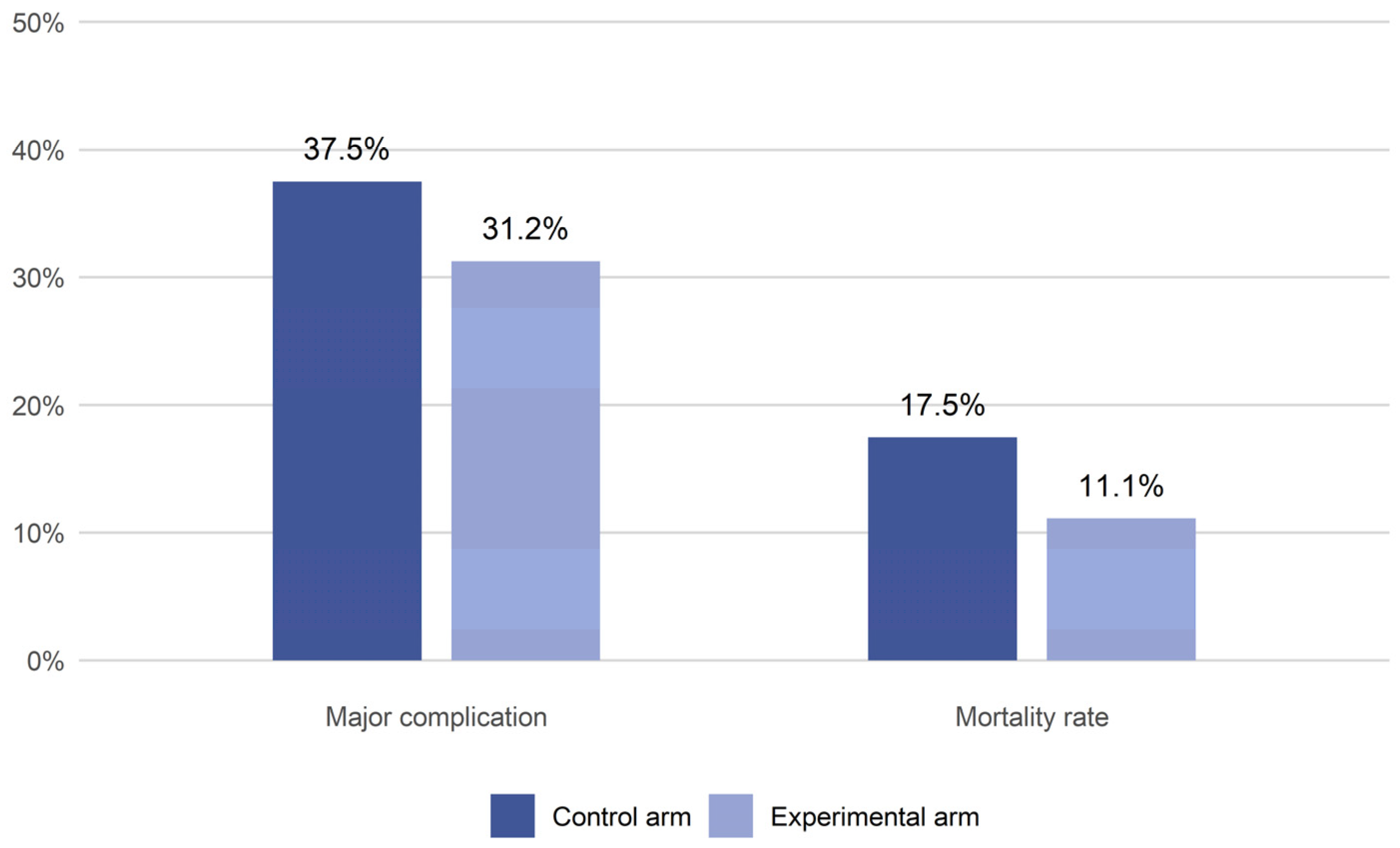

The analysis of outcomes between the experimental and control groups is shown in

Figure 4 and

Table 2.

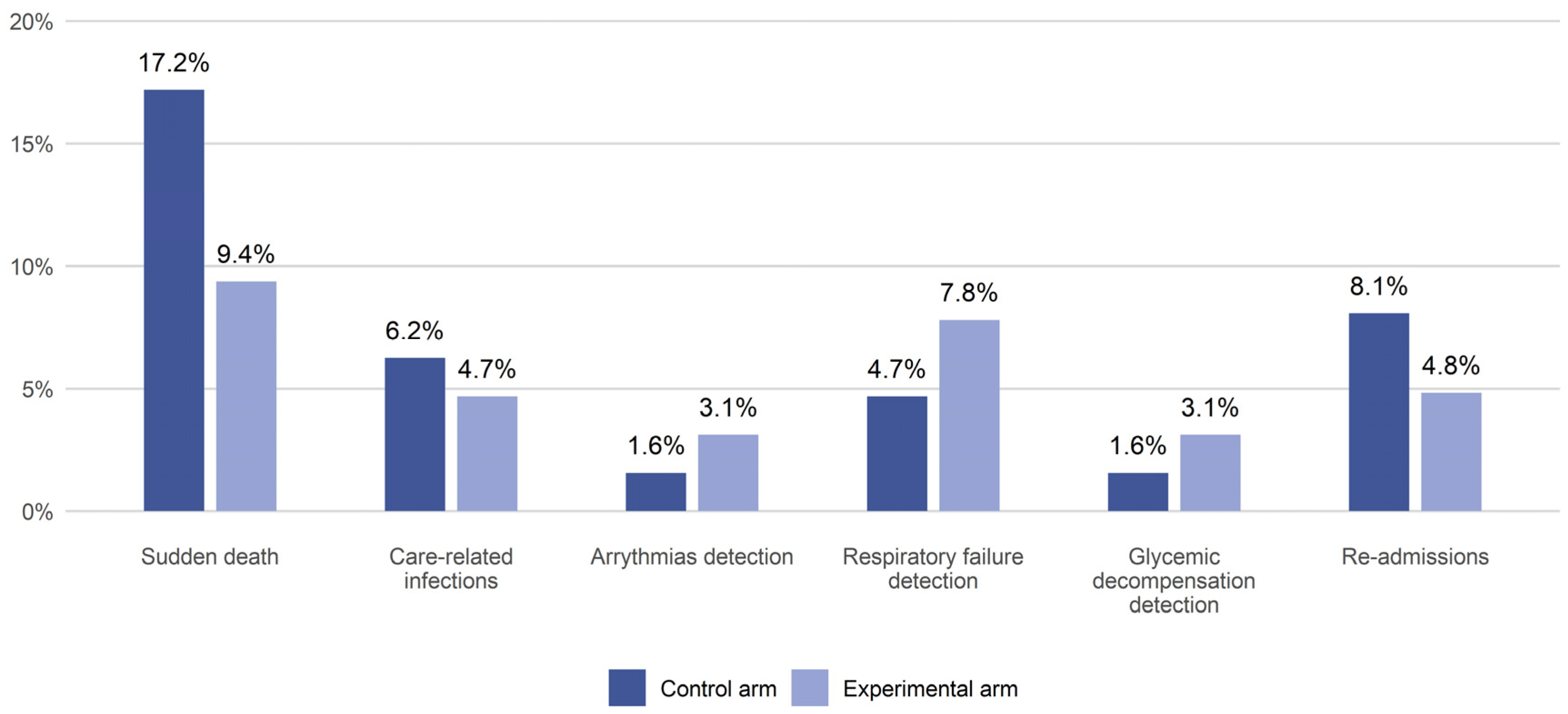

The major complications observed in both groups are displayed in

Table 2 and

Figure 4, with 80% medium-high baseline intensity in the experimental arm.

The incidence of major complications (

Figure 5) was lower in the experimental arm (31.2%) compared to the control arm (37.5%). Similarly, the rate of repeated readmissions within 21 days post-discharge was lower in the experimental group (0%) vs. the control group (1.6%), and the median Length of Stay (LOS) was slightly longer in the experimental arm (10 days) compared to the control arm (9 days) (

Table 2). However, all these differences were not statistically significant. A decrease in in-hospital mortality was observed in the experimental arm, with a death rate of 11.1% compared to 17.5% in the control group (

Table 2,

Figure 4). A lower rate of sudden death was also observed in the experimental arm (9.4%) compared to the control arm (17.2%). Furthermore, these reductions were not statistically significant, and neither was the reduction in the proportion of patients in the experimental group who were discharged directly home (55.6% vs. 44.4%). Meanwhile, the experimental arm showed a statistically significant higher use of step-down care facilities (44.2% vs. 17.4%). More than 30% of the patients meet the criteria defining end-stage disease (a positive answer to the “surprise question”: “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?”); 36.9% in the experimental arm and 33.3% in the control arm. Preliminary results have failed to confirm the hypothesis regarding reduction in hospital stay, showing, on the contrary, increased LOS in the experimental arm. This result is probably due to the evidence that in the experimental arm, the BRASS > 20 (needed for discharge planning) is higher (43.8% versus 35.9%).

Importantly, the intervention contributed to a substantial reduction in nursing workload, particularly by decreasing the time spent monitoring vital signs. The median estimated time saved was 24.4 min per patient per day, reflecting the intervention’s potential to enhance nursing resource allocation and improve workflow efficiency.

Twenty-two percent of patients in the WVPCM group (15/68) experienced discomfort with the device resulting in its removal.

A total of 16 nurses out of 18 staff members at ASST Garda, Manerbio Hospital, and involved in the LIMS completed the survey. Gender information was not collected, as it was not relevant to the research objectives, while the nurses were asked for their age and years of professional experience to provide an overview of the participant’s background.

Table 3 presents the questions included in the survey.

The main findings of the internal survey reflect the healthcare staff’s perspectives on the Local Health Authority change management strategy regarding the adoption of wireless monitoring systems.

The survey results indicate that healthcare staff were generally satisfied with the organization’s initiative and the new patient care model. Opinions on the wireless device for patient monitoring were particularly favorable: 68.8% of respondents observed a significant improvement in patient management, while 25% noted a moderated improvement, and only 6.2% noticed a minor improvement. Most participants (62.5%) considered remote monitoring clearly superior to traditional in-person visits, as it allows healthcare providers to focus more on the patients’ needs, while the system automatically collected clinical data. In terms of usability, 69% of participants found the device easy to use after a brief practice period, and the remaining 31% describe it as very intuitive from the start. The system’s short setup time and integration with the hospital’s Wi-Fi contributed to the positive evaluation. Over 80% of respondents noticed a reduction in the time needed to analyze vital parameters, with 38% reporting a significant decrease, 44% a slight decrease, and 18% minimal change. All participants recognized the safety benefits of the system, as improved surveillance allows prompt intervention in cases of clinical deterioration. Real time monitoring facilitates a clearer view of health status progress, allowing for personalized and timely interventions that improve the quality of care. 62.5% of respondents strongly agreed that digitalization and remote monitoring can significantly help the patient care pathway, while the remaining 37.5% considered the impact to be moderately significant.

The survey not only showed overall satisfaction but also revealed important key lessons regarding the implementation of wireless monitoring systems. Nurses identified Wi-Fi connectivity as a critical factor. Although most participants valued the reliable performance in areas with strong Wi-Fi coverage, some experienced brief interruptions in data transmission where signal strength was weaker, demonstrating the importance of network infrastructure before wide deployment. Alarm management also posed additional challenges. In some cases, nurses reported alarm fatigue caused by frequent non-critical alerts, indicating that tailored alarm thresholds are essential to optimize the system’s clinical benefit while preventing overburdening staff.

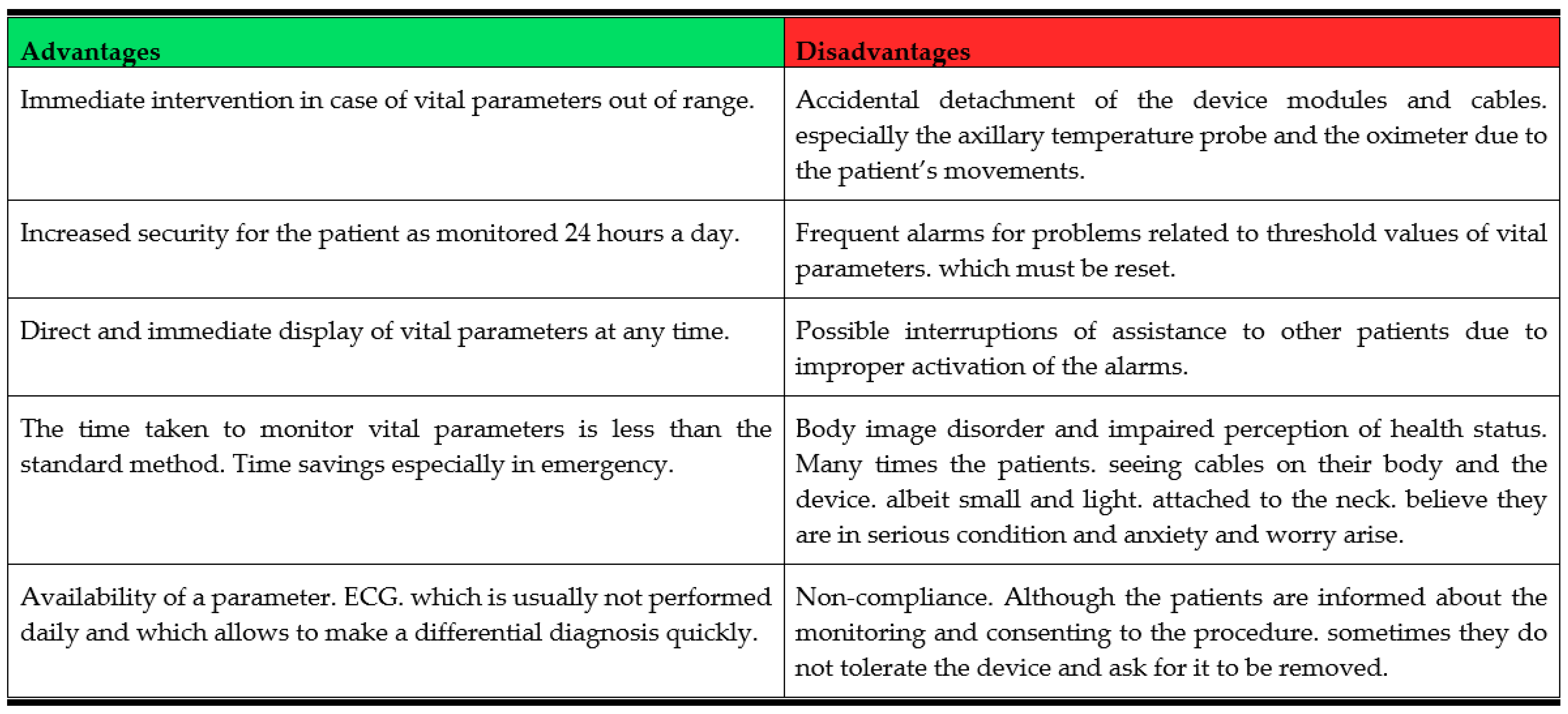

Figure 6 presents a summary of the main advantages and disadvantages of the wireless monitoring system as reported by healthcare personnel.

4. Limitations of the Study

Although this is one of the few randomized studies addressing uncertainty about the effectiveness of wireless monitoring of complex in-patients with multiple co-morbidities frequently admitted to Internal Medicine (IM) units, its various limitations should be acknowledged and are instrumental to guiding further research. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, this study was prematurely stopped. The problems related to the sanitization of devices and the closure of Internal Medicine departments within Italian hospitals in favor of special COVID-19 wards prevented the recruitment of a sufficient number of patients to achieve the adequate study power and statistical significance. The study involved only 143 patients for the analysis, which is a relatively small sample size compared to the 296 patients that were originally planned to be enrolled. This reduction in sample size decreased the study’s power from 80% to 52%. So, although the direction of the study results seems to point in the direction of the possible effectiveness of WVPCM, the smaller sample size made these findings more uncertain. Furthermore, long-term outcomes, such as chronic disease progression or quality of life after discharge, were not assessed. In addition, the study does not provide a comprehensive economic analysis as it exclusively relies on indirect proxies such as reductions in complications and nursing care demands. Future research can conduct a full economic assessment of monitoring device use. Additionally, these savings should be carefully compared with the initial implementation and maintenance costs of continuous monitoring devices to offer a more complete understanding of their economic impact. In conclusion, this study focuses on a single device—the WIN@Hospital—whose relative efficacy against other devices needs further research.

5. Related Work Section

Despite a major growth in research on WVPCM, existing academic studies remain focused on surgical, post-operative, and high-dependency units, where patient profiles and monitoring needs are steady and relatively homogenous. In contrast, general IM units usually rely on intermittent monitoring despite being responsible for a varied group of acutely ill, older, and clinically unstable patients. To date, very few studies have investigated the feasibility, effectiveness, and organizational impact of WVPCM in IM units, leaving a significant gap in the literature. Furthermore, while previous studies offer cost considerations, formal or proxy-based evaluations of cost-effectiveness remain scarce, particularly in IM settings where efficient resource employment is critical [

29].

A previous pilot investigation by Pietrantonio et al. (2019) [

22] initiated the exploration of WVPCM in Internal Medicine but was limited by a small sample and single-center design. No subsequent randomized trials or qualitative studies assessing healthcare staff perspectives have expanded this work.

The present LIMS contributes to addressing this gap. It is one of the first randomized controlled studies to evaluate WVPCM in Internal Medicine units and extends previous evidence both in scale and scope, by involving more participating centers and enrolled more patients than in the previous study. It combines quantitative clinical outcomes with qualitative insights from nurses, offering a more comprehensive understanding of device usability, workflow effects, and perceived benefits. In conclusion, it provides preliminary proxy indicators of organizational value, including time saved in vital sign monitoring and readmission trends, generating foundational data for future economic evaluations.

By addressing these underexamined aspects, the LIMS improves current knowledge on how WVPCM can be adapted to complex hospital environments beyond surgical units.

6. Discussion

In Italy, over half of hospital admissions originate from the emergency department, with Internal Medicine (IM) units receiving about 27% of these cases, most of whom are acutely ill, older, and medically complex patients [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Ideally, an effective organization should require a careful evaluation of hospitalization needs and collaboration with other specialties such as geriatrics to address frailty and social factors [

34,

35,

36]. Once admitted, each patient should have a prioritized care plan and a clearly defined multidisciplinary team based on individual medical needs [

37,

38,

39]. The use of continuous monitoring devices should be assessed at the time of admission, based on the patient’s care plan and clinical needs [

40,

41].

In this context, continuous wireless monitoring devices can be useful in the management of critically ill patients. Continuous monitoring could allow detecting different acute conditions more effectively, which is likely to reflect enhanced monitoring and diagnostic capabilities rather than an increase in their occurrence.

Regarding hospital cost analysis, the use of continuous monitoring devices is linked to a decrease in major complications, which could potentially suggest a slight reduction in costs.

Indeed, average costs per hospitalization increase with the number of comorbidities. According to the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the mean cost per hospital stay is approximately US

$ 7300 for patients without comorbidities, US

$ 9000 for those with one or two comorbidities, and about US

$ 12,300 for patients with three or more [

42].

However, this may reflect a more organized care approach that prioritizes patient safety and continuity over rapid discharge. This is further supported by a higher propensity of step-down care for continuously monitored patients rather than direct discharge at home for standard care patients. Critically ill patients face many challenges when discharged at home if they have no adequate social and economic support that allow them to continue their care effectively. In addition, continuous monitoring can be readily extended with telemonitoring devices in step-down care facilities where professional healthcare staff can be trained even if they have not qualified as nurses [

24]. Hospital Information Technology systems can be easily made compatible with step-down facilities [

40]. Conversely, applying continuous monitoring at home may require different telemonitoring devices [

43], must be self-managed with all the challenges if the support is not adequate, and the monitoring and intervention systems in case of adverse events is more challenging to set [

44].

Although the advantages in employing WVPCM in different hospital settings are well-documented, its clear and widely accepted impact on patient conditions still requires rigorous investigation [

45,

46]. Considering these complexities, research and evidence are still necessary to better understand the feasibility and the effectiveness of WVPCM devices in specific hospital settings. On the basis of these premises, we therefore planned to carry out a study with the aim of assessing whether the use of WVPCM could improve clinical outcomes.

The study did not enroll the number of patients originally planned because of the COVID-19 outbreak and was prematurely stopped. Due to the reduced sample size, the results of this study are affected by a reduction in statistical power. The study showed a positive trend in the reduction of major complications, which was the primary outcome, not statistically significant. Statistical significance was also not reached for secondary outcomes.. Continuous monitoring devices notably reduce the amount of time nurses need to dedicate to each patient. This finding supports academic literature [

43,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53] that suggests continuous monitoring improves nurses’ working environments in patient management. This is particularly relevant in IM wards, where staff often operate under stressful and understaffed conditions [

54,

55].

The study also investigated the nurses’ qualitative perceptions of these devices, revealing that they are generally viewed positively in terms of patient management, relationships, and safety. Most respondents believe that digitalization and remote monitoring can significantly improve the patient care pathway. Moreover, the reported reduction in care time reflects a growing trust and reliance on the devices once the initial training and implementation phases are completed. As nursing time is a key indicator of hospital costs, continuous monitoring devices can help improve operational efficiency and ultimately contribute to cost reduction.

Although the quantitative study results show a statistically significant reduction in the time healthcare personnel spend per patient, there is only limited awareness among staff of the advantages of using the device. These findings highlight the need for adequate training to effectively integrate it into clinical processes.

In our study, the monitored group experienced a higher number of detections for serious, life-threatening conditions, and the control group had twice the rate of sudden death, although the results were not statistically significant.

Moreover, we wanted to verify how the adoption of new technologies can benefit hospital management. The most relevant data in this area are those relating to readmissions after discharge and the reduction in time spent by nurses per patient. Result analyses showed that rehospitalization after 21 days was reduced for monitored patients. Although this outcome was not statistically significant, the result could suggest the idea of alternative organizational models capable of improving performance in terms of reducing costs and length of hospital stay, but at the same time guaranteeing a high level of care delivery.

Further research should focus on accomplishing larger-scale, multi-center randomized controlled trials with varied follow-up periods to further assess clinical efficacy and long-term outcomes. It would be important to include a wide range of medical fields with a diverse patient population and incorporate different care environments, such as step-down facilities and home care settings. Additionally, research should test different and more modern devices to compare their relative efficacy and advise on the most suitable solutions for different contexts. This study, in fact, showed that a few patients in the WVPCM group experienced discomfort with the device, resulting in its removal.

A comprehensive evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of these monitoring devices is also necessary with an estimation of their actual life-cycle costs for healthcare systems. Finally, the perspectives of both healthcare professionals and patients should be explored, as well as the broader impact on hospital settings.

7. Conclusions

This study is not able to demonstrate a statistically significant difference at the clinical or operational level; however, it shows a positive trend in terms of major complications and mortality.

In any case, the use of devices substantially reduces the nurse workload and allows them to focus on more complex clinical duties.

The integration of monitoring systems into Internal Medicine hospital settings represents a promising opportunity in acute care patient management; therefore, further studies with large sample sizes are needed to show the potential of continuous monitoring devices to improve the safety and quality of care for critically ill complex patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P., A.S. and A.V.; Data curation, F.V., M.D.C., M.P. and E.A.; Formal analysis, F.P., A.S., A.R.B., F.R. and R.D.; Investigation, A.R.B., L.M., A.M. and R.D.; Methodology, F.P., A.S. and R.D.; Resources, F.P. and A.R.B.; Supervision, F.P.; Validation, A.V.; Writing—original draft, F.P. and A.S.; Writing—review and editing, F.P. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Provincial Ethics Committee of the Province of Brescia (Italy) with number NP 2659 approved on 28 February 2017, and by the Lazio 2 (Italy) Ethics Committee with number S 28.18 approved on 18 April 2018. The study was registered at Clinical trials Gov with number NCT 03050034, registered on 10 February 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Roberto Vicini and Riccardo Cuoghi Costantini for data management and Ann Elizabeth Tilley for the valuable contribution to the English revision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ER | Emergency Room |

| MEWS | Modified Early Warning Score |

| NEWS | National Early Warning Score |

| DRGs | Diagnostic Related Groups |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| SAEs | Serious Adverse Events |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| LIMS | LIght Monitor Study |

| ASST | Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale |

| CIRS-CI | Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Comorbidity Index |

| IIA | Nursing Intensity Index |

| MDCs | Major Diagnostic Categories |

| IT | Information Systems |

| CVSM | Continuous Vital Sign Monitoring |

| IM | Internal Medicine |

| LOS | Length of Stay |

References

- Vo, D.-K.; Trinh, K.T.L. Advances in Wearable Biosensors for Healthcare: Current Trends, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Biosensors 2024, 14, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.S.V.; Eriksen, V.R.; Rasmussen, S.S.; Meyhoff, C.S.; Aasvang, E.K. Time to detection of serious adverse events by continuous vital sign monitoring versus clinical practice. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2025, 69, e14541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Noort, H.H.J.; Becking-Verhaar, F.L.; Bahlman-van Ooijen, W.; Pel, M.; Van Goor, H.; Huisman-de Waal, G. Three Years of Continuous Vital Signs Monitoring on the General Surgical Ward: Is It Sustainable? A Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leenen, J.P.l.; Schoonhoven, L.; Patijn, G.A. Wearable wireless continuous vital signs monitoring on the general ward. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2024, 30, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, A.K.; Flick, M.; Saugel, B. Continuous vital sign monitoring of patients recovering from surgery on general wards: A narrative review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2025, 134, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, F.; Marelli, F.; Cesana, V.; Rossi, V.; Boasi, N.; Lusignani, M. Prevalence of Delayed Discharge Among Patients Admitted to the Internal Medicine Wards: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs Rep. 2025, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lockhorst, E.W.; Van Noordenne, M.; Klouwens, L.; Govaert, K.M.; De Bruijn, E.; Verhoef, C.; Gobardhan, P.D.; Schreinemakers, J.M.J. Improving diagnosis of early complications (<1 week) through continuous vital sign monitoring following oncological gastrointestinal surgical procedures. World J. Surg. 2024, 48, 1902–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigvardt, E.; Grønbæk, K.K.; Jepsen, M.L.; Søgaard, M.; Haahr, L.; Inácio, A.; Aasvang, E.K.; Meyhoff, C.S. Workload associated with manual assessment of vital signs as compared with continuous wireless monitoring. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2024, 68, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, G.B.; Mault, J.; Ventura, M.E.; Adams, J.; Campbell, F.J.; Tremper, K.K. A Retrospective Observational Study of Continuous Wireless Vital Sign Monitoring via a Medical Grade Wearable Device on Hospitalized Floor Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, M.C.; Bekhuis, R.E.M.; Wang, Y.; Hegeman, J.H.; Folbert, E.C.; Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.M.R.; Kalkman, C.J.; Kouwenhoven, E.A.; Hermens, H.J. Early Warning Scores to Support Continuous Wireless Vital Sign Monitoring for Complication Prediction in Patients on Surgical Wards: Retrospective Observational Study. JMIR Perioper. Med. 2023, 6, e44483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, B.A.; Motamedi, V.; Michard, F.; Saha, A.K.; Khanna, A.K. Impact of continuous and wireless monitoring of vital signs on clinical outcomes: A propensity-matched observational study of surgical ward patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 132, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, M.; Nomura, A.; Takeji, Y.; Shimojima, M.; Yoshida, S.; Kitano, T.; Ohtani, K.; Tada, H.; Takashima, S.; Sakata, K.; et al. Usefulness of the LAVITA Telemonitoring System in Patients With Heart Failure—A Feasibility Study. Circ. Rep. 2025, 7, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, S.; Bradley, S.; Chattu, V.K.; Adisesh, A.; Nurtazina, A.; Kyrykbayeva, S.; Sakhamuri, S.; Yaya, S.; Sunil, T.; Thomas, P.; et al. Telemedicine Across the Globe-Position Paper From the COVID-19 Pandemic Health System Resilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) International Consortium (Part 1). Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 556720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imberti, J.F.; Tosetti, A.; Mei, D.A.; Maisano, A.; Boriani, G. Remote monitoring and telemedicine in heart failure: Implementation and benefits. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2021, 23, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becking-Verhaar, F.L.; Verweij, R.P.H.; De Vries, M.; Vermeulen, H.; Van Goor, H.; Huisman-de Waal, G.J. Continuous Vital Signs Monitoring with a Wireless Device on a General Ward: A Survey to Explore Nurses’ Experiences in a Post-Implementation Period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodgren, G.; Rachas, A.; Farmer, A.J.; Inzitari, M.; Shepperd, S. Interactive telemedicine: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2016, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, J.; Weibelzahl, S.; Duden, G.S. Would’ve, could’ve, should’ve: A cross-sectional investigation of whether and how healthcare staff’s working conditions and mental health symptoms have changed throughout 3 pandemic years. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e076712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Peralta, S.S.; Ziaeian, B.; Chang, D.S.; Goldberg, S.; Vetrivel, R.; Fang, Y.M. Leveraging telemedicine for management of veterans with heart failure during COVID-19. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2021, 34, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Orlandini, F.; Moriconi, L.; La Regina, M. Acute Complex Care Model: An organizational approach for the medical care of hospitalized acute complex patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 26, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelucci, A.; Greco, M.; Cecconi, M.; Aliverti, A. Wearable devices for patient monitoring in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2025, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Rosiello, F.; Alessi, E.; Pascucci, M.; Rainone, M.; Cipriano, E.; Di Berardino, A.; Vinci, A.; Ruggeri, M.; Ricci, S. Burden of COVID-19 on Italian Internal Medicine Wards: Delphi, SWOT, and Performance Analysis after Two Pandemic Waves in the Local Health Authority “Roma 6” Hospital Structures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Bussi, A.R.; Amadasi, S.; Bresciani, E.; Caldonazzo, A.; Colombini, P.; Giovannini, M.S.; Grifi, G.; Lanzini, L.; Migliorati, P.; et al. Technological Challenges set up by Continuous Wireless Monitoring designed to Improve Management of Critically Ill Patients in an Internal Medicine Unit (LIMS study): Study Design and Preliminary Results. J. Community Prev. Med. 2019, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siragusa, L.; Angelico, R.; Angrisani, M.; Zampogna, B.; Materazzo, M.; Sorge, R.; Giordano, L.; Meniconi, R.; Coppola, A.; SPIGC Survey Collaborative Group; et al. How future surgery will benefit from SARS-CoV-2-related measures: A SPIGC survey conveying the perspective of Italian surgeons. Updat. Surg. 2023, 75, 1711–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Vinci, A.; Rosiello, F.; Alessi, E.; Pascucci, M.; Rainone, M.; Delli Castelli, M.; Ciamei, A.; Montagnese, F.; D’Amico, R.; et al. Green Line Hospital-Territory Study: A Single-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial for Evaluation of Technological Challenges of Continuous Wireless Monitoring in Internal Medicine, Preliminary Results. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Vinci, A.; Maurici, M.; Ciarambino, T.; Galli, B.; Signorini, A.; La Fazia, V.M.; Rosselli, F.; Fortunato, L.; Iodice, R.; et al. Intra- and Extra-Hospitalization Monitoring of Vital Signs—Two Sides of the Same Coin: Perspectives from LIMS and Greenline-HT Study Operators. Sensors 2023, 23, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win@hospital. 01Health. Available online: https://www.01health.it/applicazioni/telemedicina/winhospital-sistema-italiano-monitoraggio-paziente/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- DEATH. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/68003643 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Complication. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/68048909 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Fueglistaler, P.; Adamina, M.; Guller, U. Non-Inferiority Trials in Surgical Oncology. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 14, 1532–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachabayov, M.; Sharun, K.; Felsenreich, D.M.; Nainu, F.; Anwar, S.; Yufika, A.; Ophinni, Y.; Yamada, C.; Fahriani, M.; Husnah, M.; et al. Perceived risk of infection and death from COVID-19 among community members of low- and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study. F1000Research 2022, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Li, Y.L.; Wei, M.Y.; Li, G.Y. Innovation and challenges of artificial intelligence technology in personalized healthcare. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Piasini, L.; Spandonaro, F.; Li, G.Y. Internal Medicine and emergency admissions: From a national Hospital Discharge Records (SDO) study to a regional analysis. Ital. J. Med. Ital. J. Med. 2016, 10, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Florczak, M.; Kuhn, S.; Kärberg, K.; Leung, T.; Said Criado, I.; Sikorski, S.; Ruggeri, M.; Signorini, A.; Rosiello, F.; et al. Applications to augment patient care for Internal Medicine specialists: A position paper from the EFIM working group on telemedicine, innovative technologies & digital health. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1370555. [Google Scholar]

- Harapan, H.; Yufika, A.; Anwar, S.; Ophinni, Y.; Yamada, C.; Sharun, K.; Gachabayov, M.; Fahriani, M.; Husnah, M.; Raad, R.; et al. Beliefs on social distancing and face mask practices during the COVID-19 pandemic in low- and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study. F1000Research 2022, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H.; Anwar, S.; Yufika, A.; Sharun, K.; Gachabayov, M.; Fahriani, M.; Husnah, M.; Raad, R.; Abdalla, R.Y.; Adam, R.Y.; et al. Vaccine hesitancy among communities in ten countries in Asia, Africa, and South America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pathog. Glob. Health 2022, 116, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajar, J.K.; Ilmawan, M.; Mamada, S.; Mutiawati, E.; Husnah, M.; Yusuf, H.; Nainu, F.; Sirinam, S.; Keam, S.; Ophinni, Y.; et al. Global prevalence of persistent neuromuscular symptoms and the possible pathomechanisms in COVID-19 recovered individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Narra J. 2021, 1, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahriani, M.; Ilmawan, M.; Fajar, J.K.; Maliga, H.A.; Frediansyah, A.; Masyeni, S.; Yusuf, H.; Nainu, F.; Rosiello, F.; Sirinam, S.; et al. Persistence of long COVID symptoms in COVID-19 survivors worldwide and its potential pathogenesis—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Narra J. 2021, 1, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buowari, D.Y.; Rosiello, F.; Ayowole, D.; Maki, L. Beyond the Number, Balancing Epidemiological Reporting with the Need for Patient Empathy During the COVID-19 Pandemic. World Med. J. 2021, 67, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remuzzi, A.; Remuzzi, G. COVID-19 and Italy: What next? Lancet 2020, 395, 1225–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, I.; Kim, W.; Lim, Y.; Kang, E.; Kim, J.; Chung, H.; Kim, J.; Kang, E.; Jung, Y.B. Strategy for scheduled downtime of hospital information system utilizing third-party applications. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, T.J.; Linde, M.; Schnell-Inderst, P. A universal outcome measure for headache treatments, care-delivery systems and economic analysis. J. Headache Pain 2021, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), National Inpatient Sample (NIS), [Internet]. 2019. Available online: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NISIntroduction2019.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Serrano, L.P.; Maita, K.C.; Avila, F.R.; Torres-Guzman, R.A.; Garcia, J.P.; Eldaly, A.S.; Haider, C.R.; Felton, C.L.; Paulson, M.R.; Maniaci, M.J.; et al. Benefits and Challenges of Remote Patient Monitoring as Perceived by Health Care Practitioners: A Systematic Review. Perm. J. 2023, 27, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Varnfield, M.; Jayasena, R.; Celler, B. Home telemonitoring for chronic disease management: Perceptions of users and factors influencing adoption. Health Inform. J. 2021, 27, 1460458221997893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.M.; Khera, N.; Elugunti, P.R.; Ruff, K.C.; Hommos, M.S.; Thomas, L.F.; Nagaraja, V.; Garrett, A.L.; Pantoja-Smith, M.; Delafield, N.L.; et al. The State of Remote Patient Monitoring for Chronic Disease Management in the United States. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e70422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockey-Bartlett, C.; Morelli, J.; Coffel, M.; Geracitano, J.; Lafata, J.E.; Khairat, S. Effect of remote patient monitoring on healthcare use among patients with cancer: A systematic review. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076251384220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thekkan, K.R.; Genna, C.; Ferro, F.; Cecchetti, C.; Dall’Oglio, I.; Tiozzo, E.; Raponi, M.; Gawronski, O.; Ped V-Scale Studygroup. Pediatric vital signs monitoring in hospital wards: Recognition systems and factors influencing nurses’ attitudes and practices. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2023, 73, e602–e611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekelman, D.B.; Feser, W.; Morgan, B.; Welsh, C.H.; Parsons, E.C.; Paden, G.; Baron, A.; Hattler, B.; McBryde, C.; Cheng, A.; et al. Nurse and Social Worker Palliative Telecare Team and Quality of Life in Patients With COPD, Heart Failure, or Interstitial Lung Disease: The ADAPT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 331, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Dailey, K.; Frazier, S.; Bressler, S.; King-Wilson, J. The Role of Nurse Practitioners in the Management of Heart Failure Patients and Programs. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2022, 24, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speyer, R.; Denman, D.; Wilkes-Gillan, S.; Chen, Y.; Bogaardt, H.; Kim, J.; Heckathorn, D.; Cordier, R. Effects of telehealth by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 50, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liang, N.; Bu, F.; Hesketh, T. The Effectiveness of Self-Management of Hypertension in Adults Using Mobile Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.H.; Lieu, N.; Tang, Y.; Browne, D.S.; Agusala, B.; Liao, J.M. Trends in utilization of remote monitoring in the United States. Health Affairs Scholar. Health Aff. Sch. 2025, 3, qxaf115. [Google Scholar]

- Bouabida, K.; Chaves, B.G.; Anane, E.; Jagram, N. Navigating the landscape of remote patient monitoring in Canada: Trends, challenges, and future directions. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1523401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartenberg, C.; Elden, H.; Frerichs, M.; Jivegård, L.L.; Magnusson, K.; Mourtzinis, G.; Nyström, O.; Quitz, K.; Sjöland, H.; Svanberg, T.; et al. Clinical benefits and risks of remote patient monitoring: An overview and assessment of methodological rigour of systematic reviews for selected patient groups. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Duncan, D. Remote Patient Monitoring Applications in Healthcare: Lessons from COVID-19 and Beyond. Electronics 2025, 14, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).