A Design of Rectifier with High-Voltage Conversion Gain in 65 nm CMOS Technology for Indoor Light and RF Energy Harvesting

Abstract

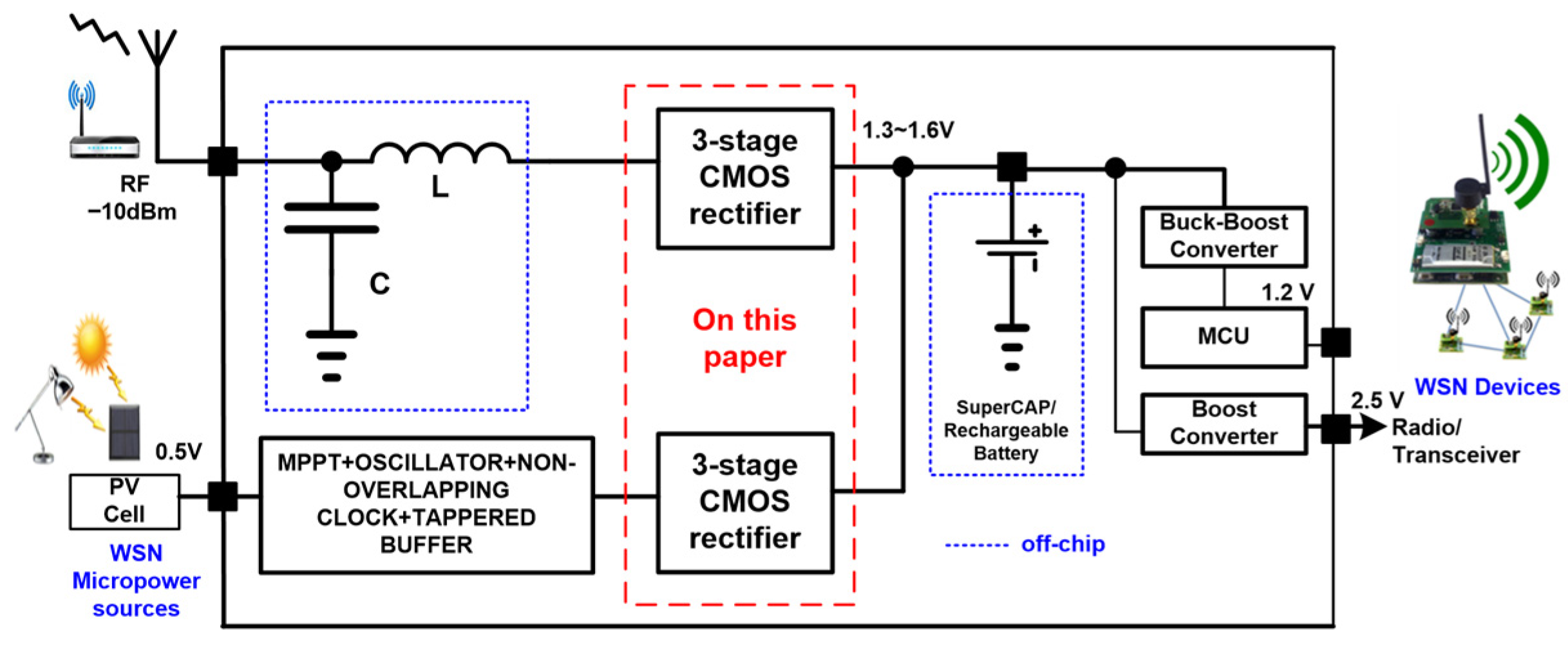

1. Introduction

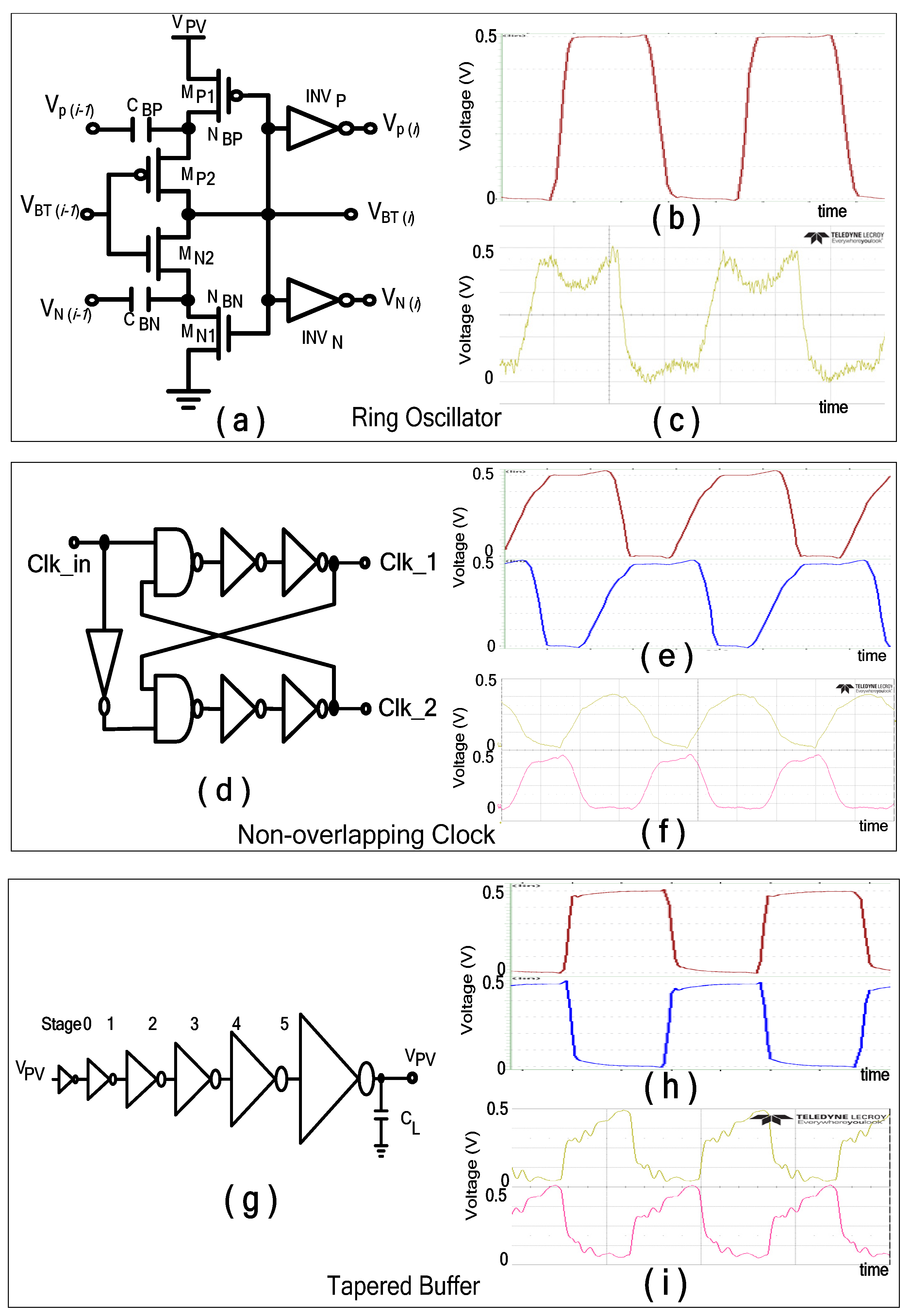

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definitions and Notation

2.2. Rectifier Architecture and Operation

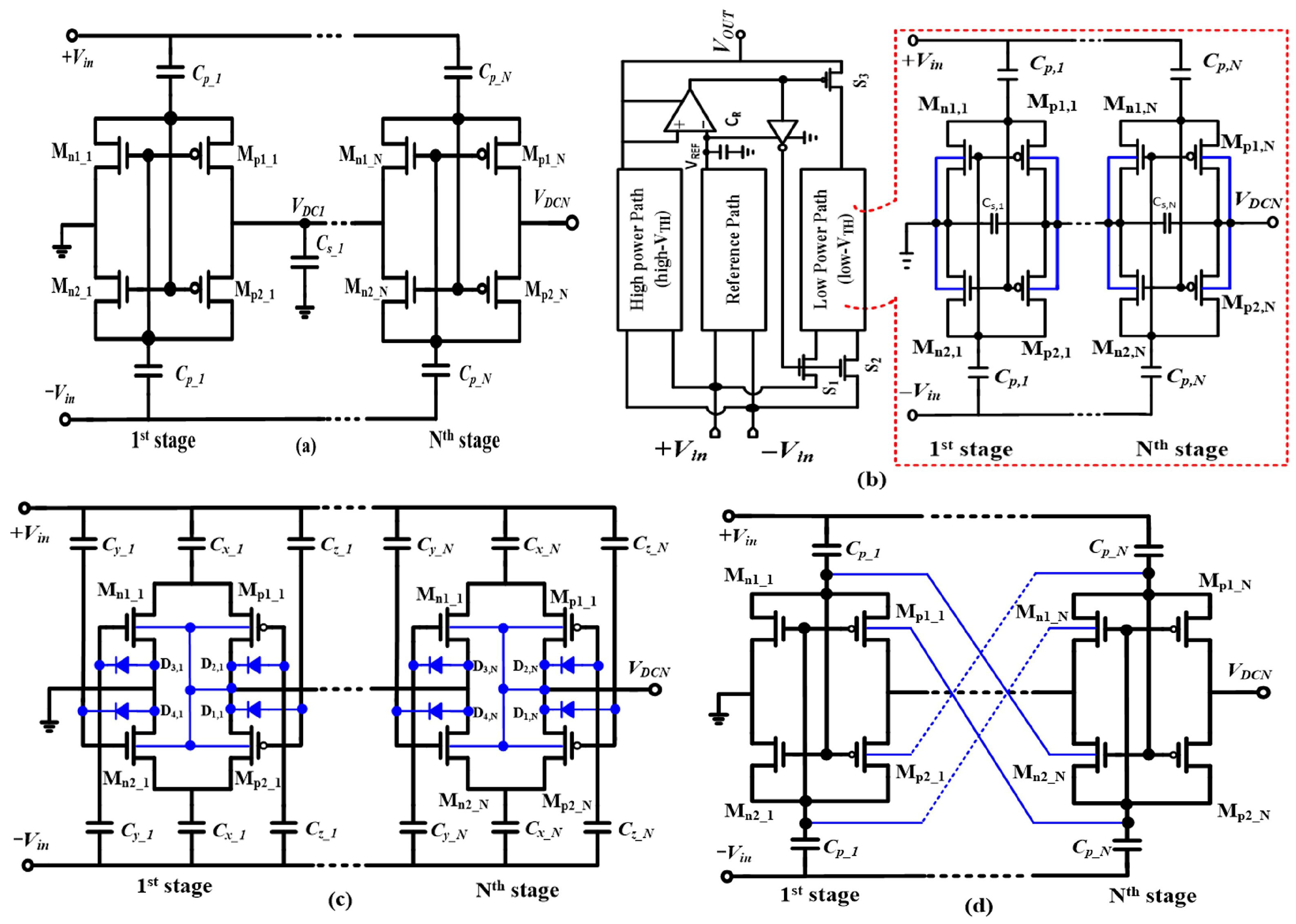

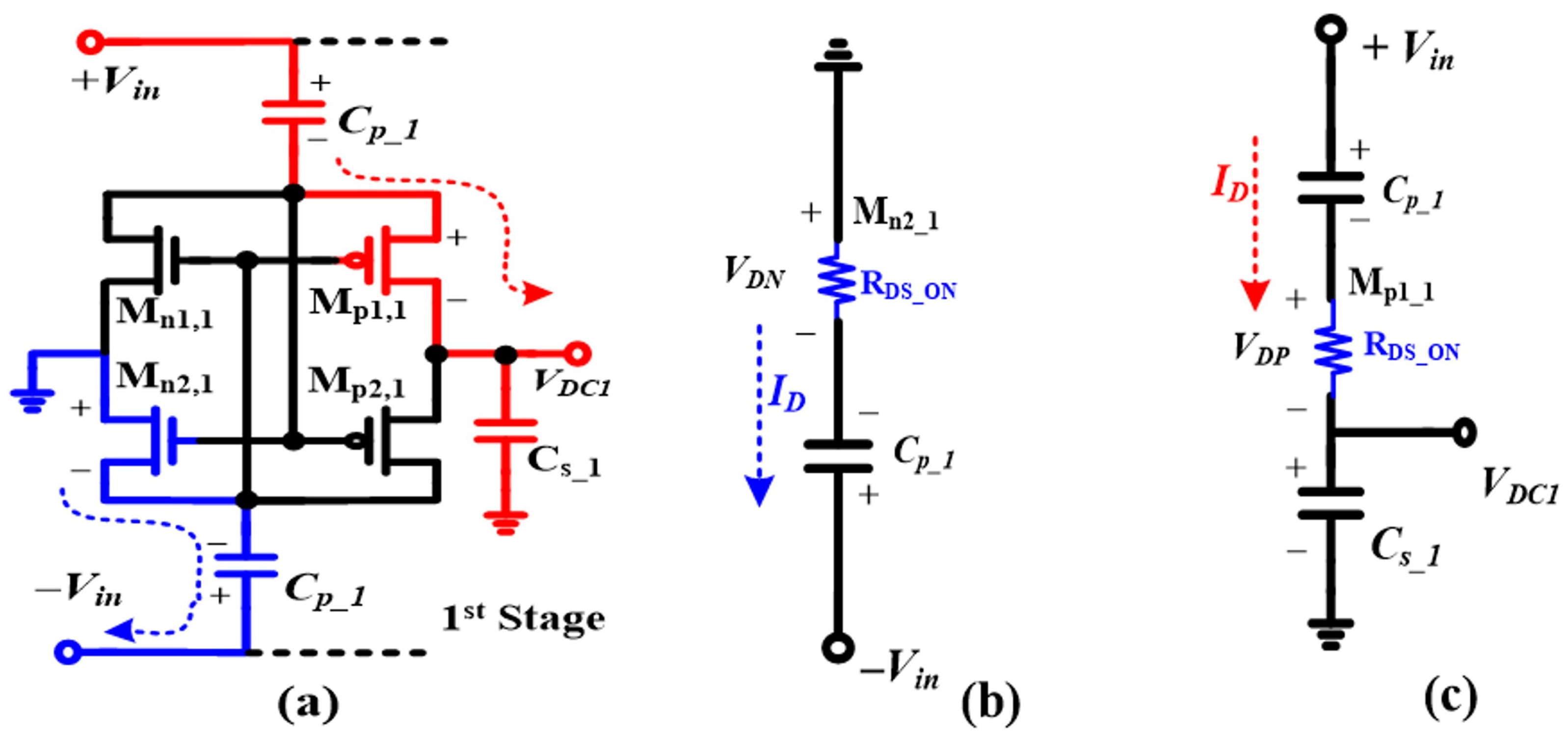

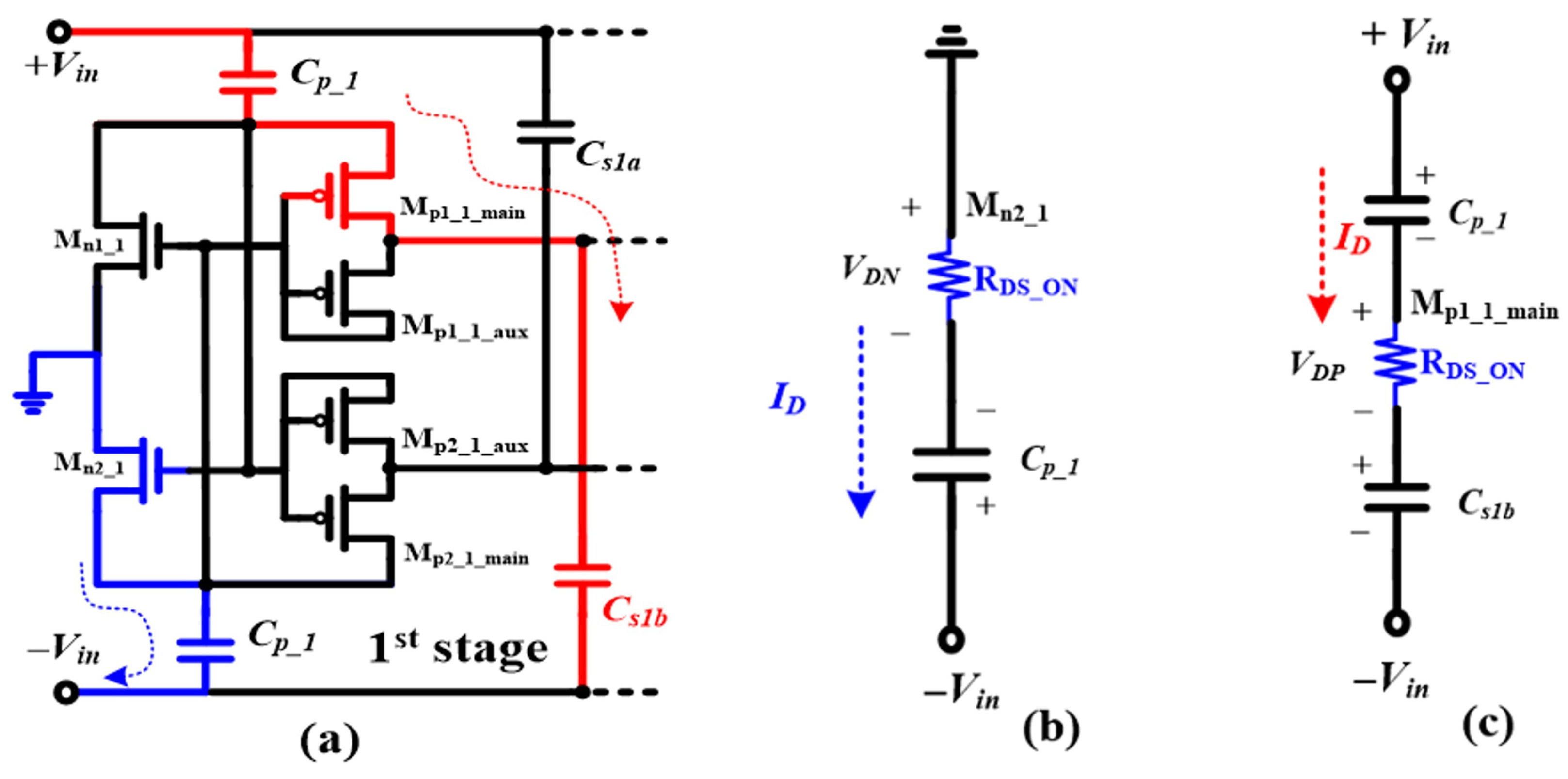

2.3. Analysis of Conventional CCDD Circuit Structure

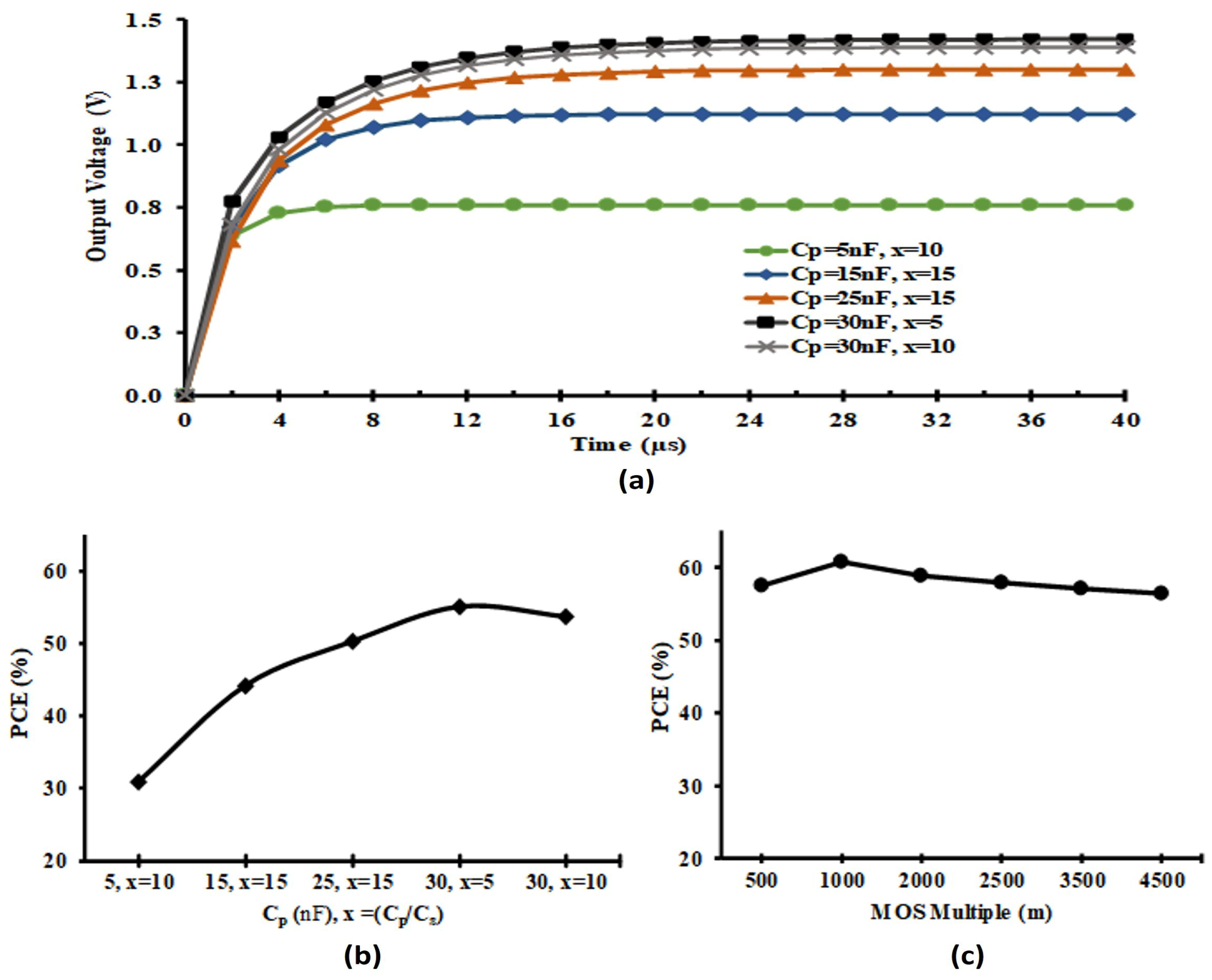

2.4. Study of the Capacitor-Based CCDD Rectifier Topology

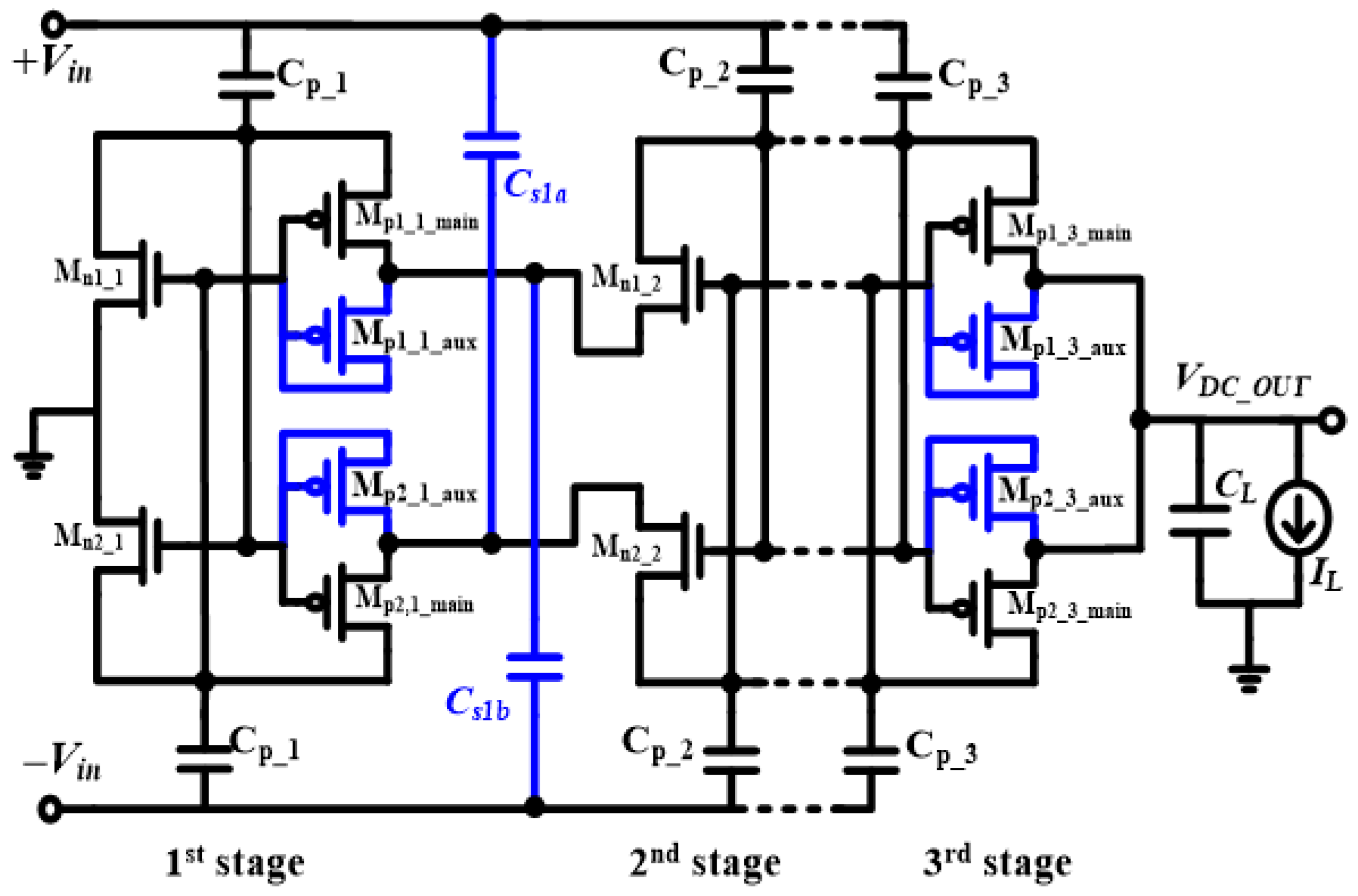

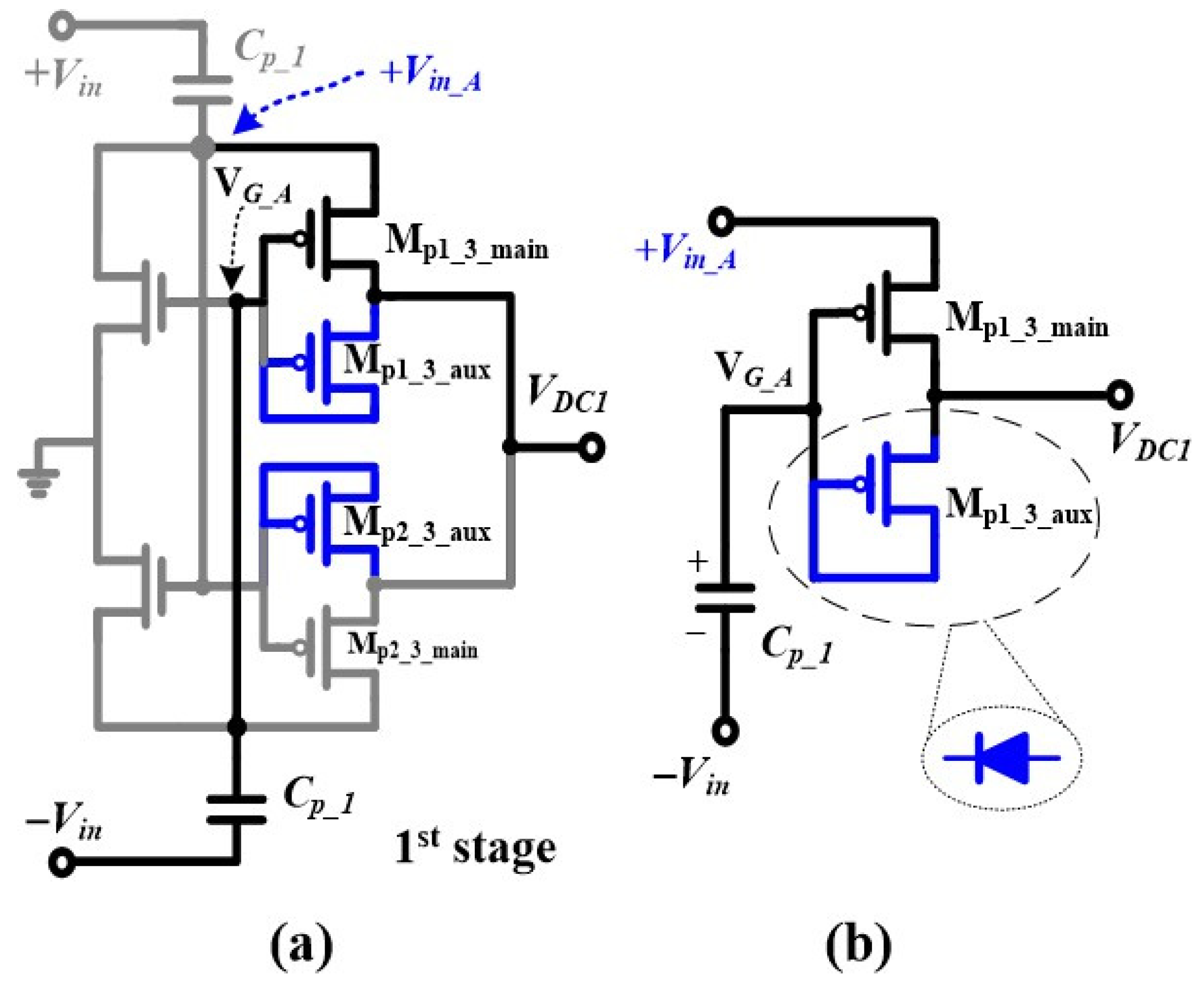

2.5. Analysis of the Auxiliary Path Designed to Boost PCE

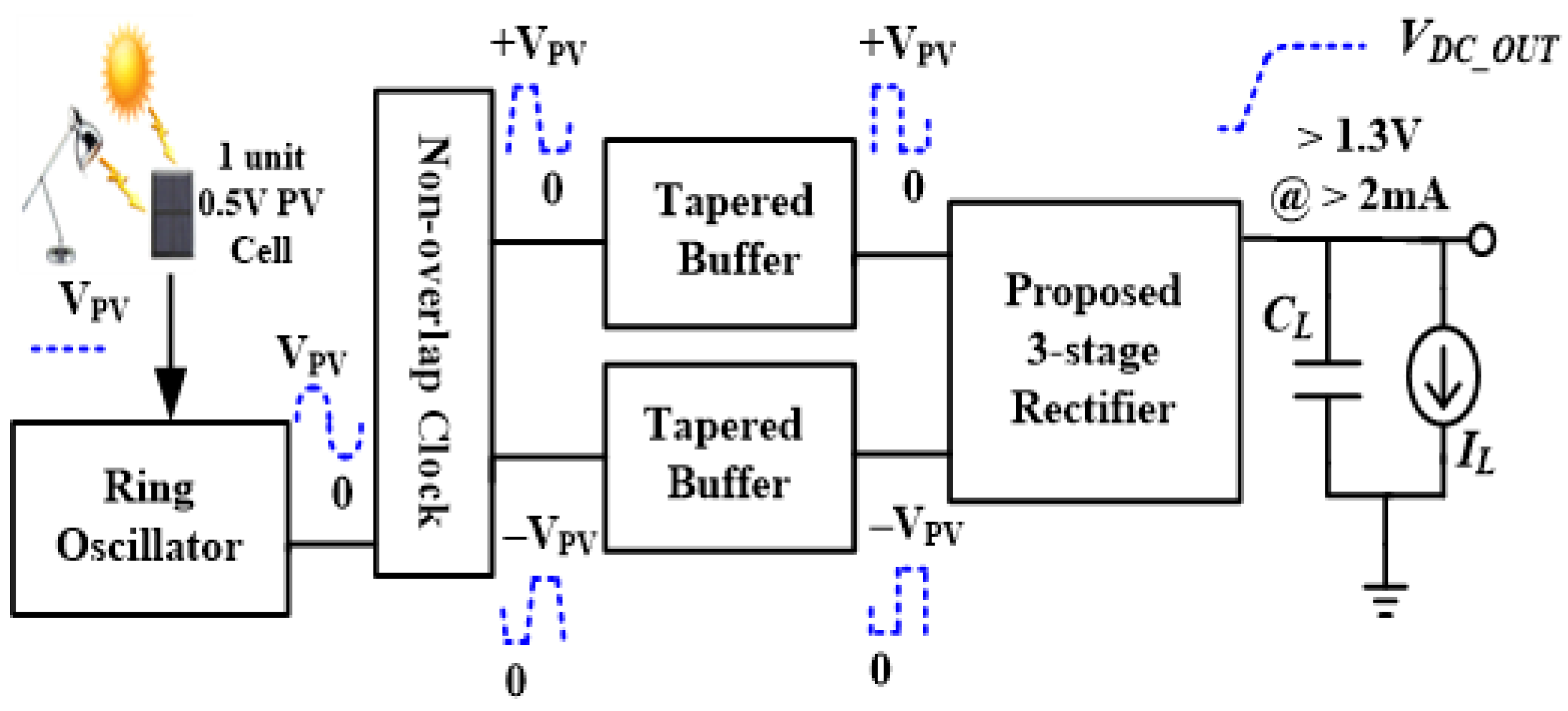

2.6. Indoor Light Energy Harvesting Rectifier Design

- The capacitor (CL) and load resistor (RL) were set to initial values of 1 nF and 100 Ω, respectively.

- The pump capacitor CP was chosen to be 15× larger than each storage capacitor (CS1a and CS1b); thus, CP was set to 10 nF.

- Initial transistor dimensions were PMOS width WP = 3 µm, NMOS width WN = 1 µm, and channel length L = 0.1 µm. Larger widths may later be selected to further lower RDS_ON

- Device multiplicity was set with multiplier m = 500 and finger count f = 2.

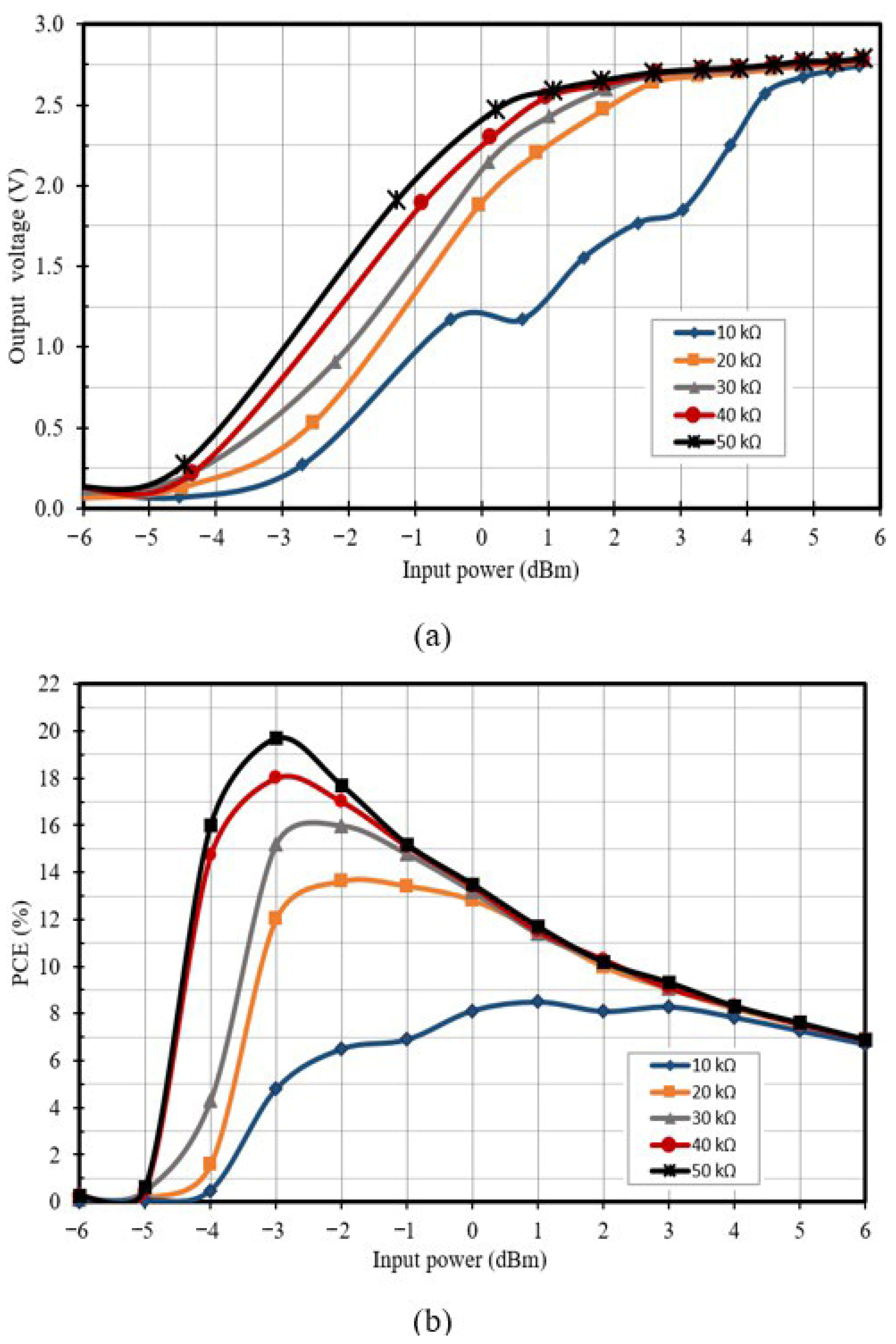

2.7. Rectifier Design for 2.4 GHz RF Energy Harvesting

3. Results

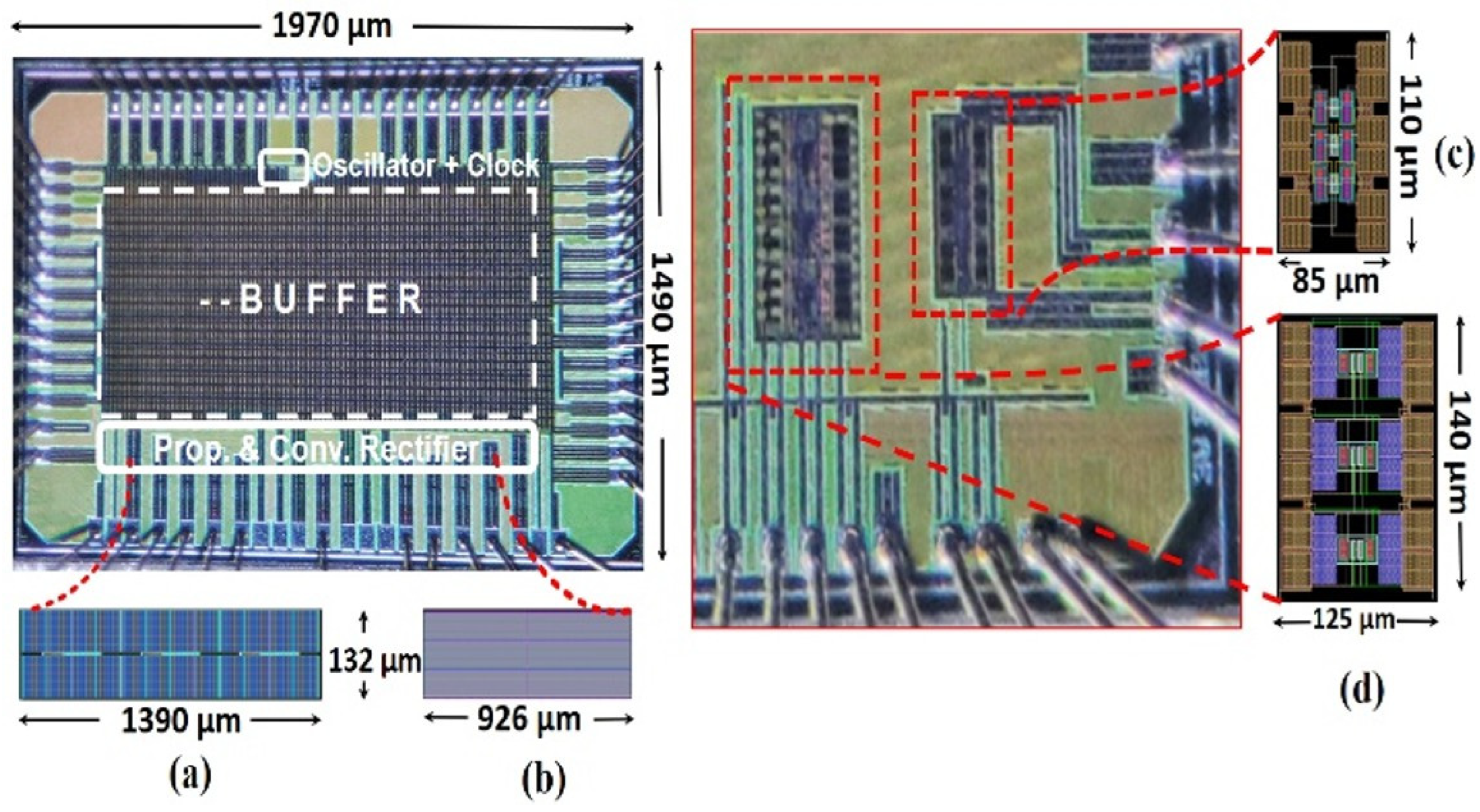

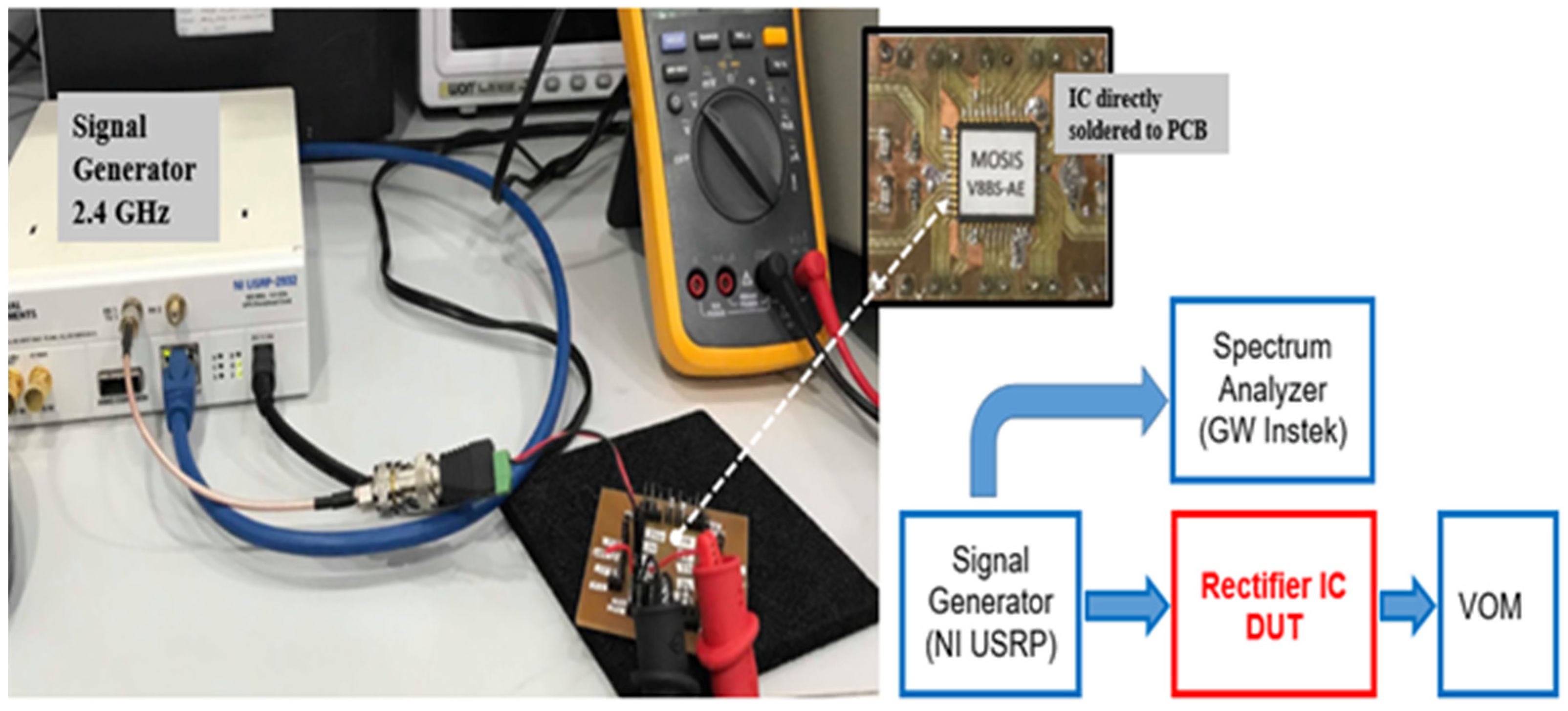

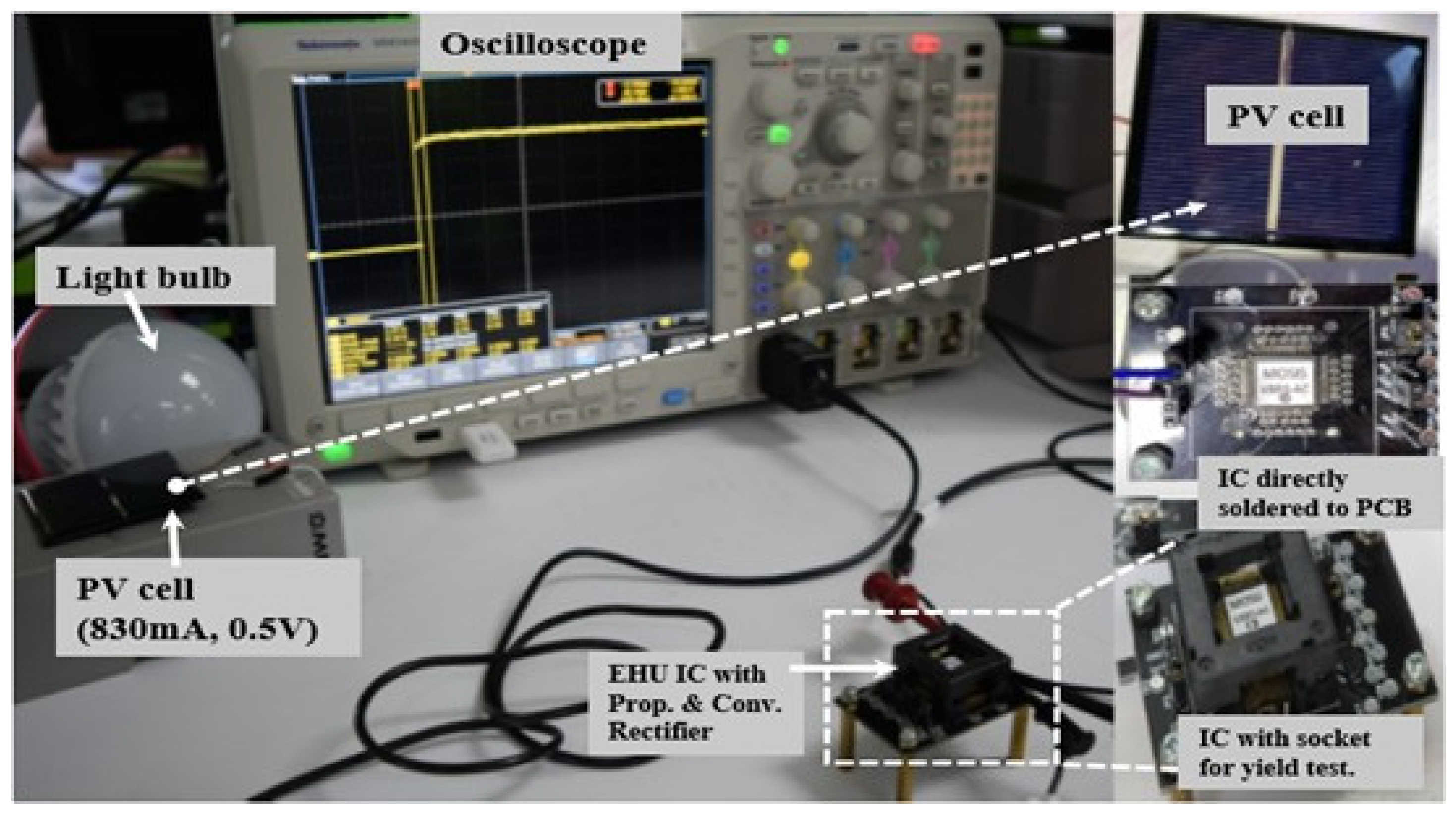

3.1. Measurement Setup

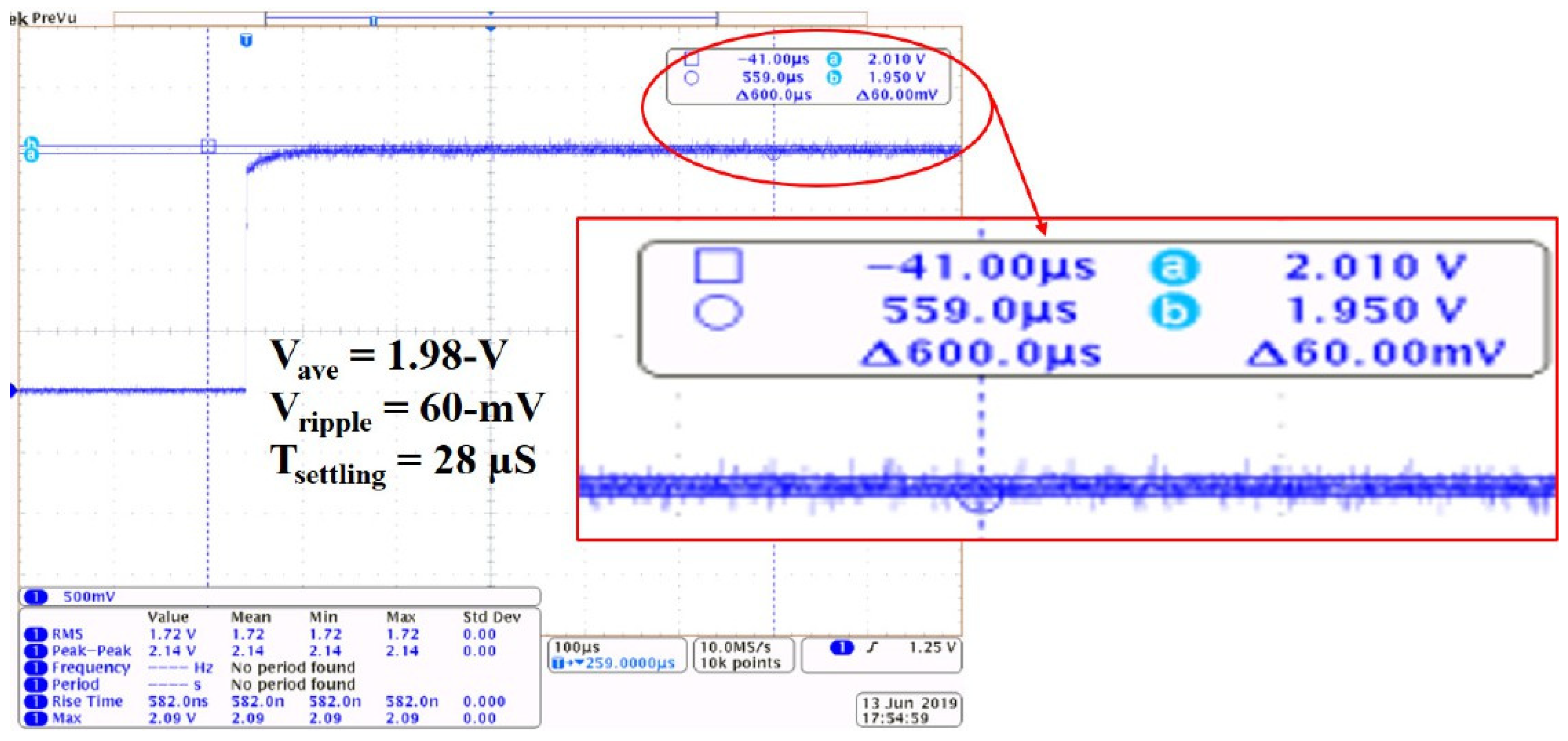

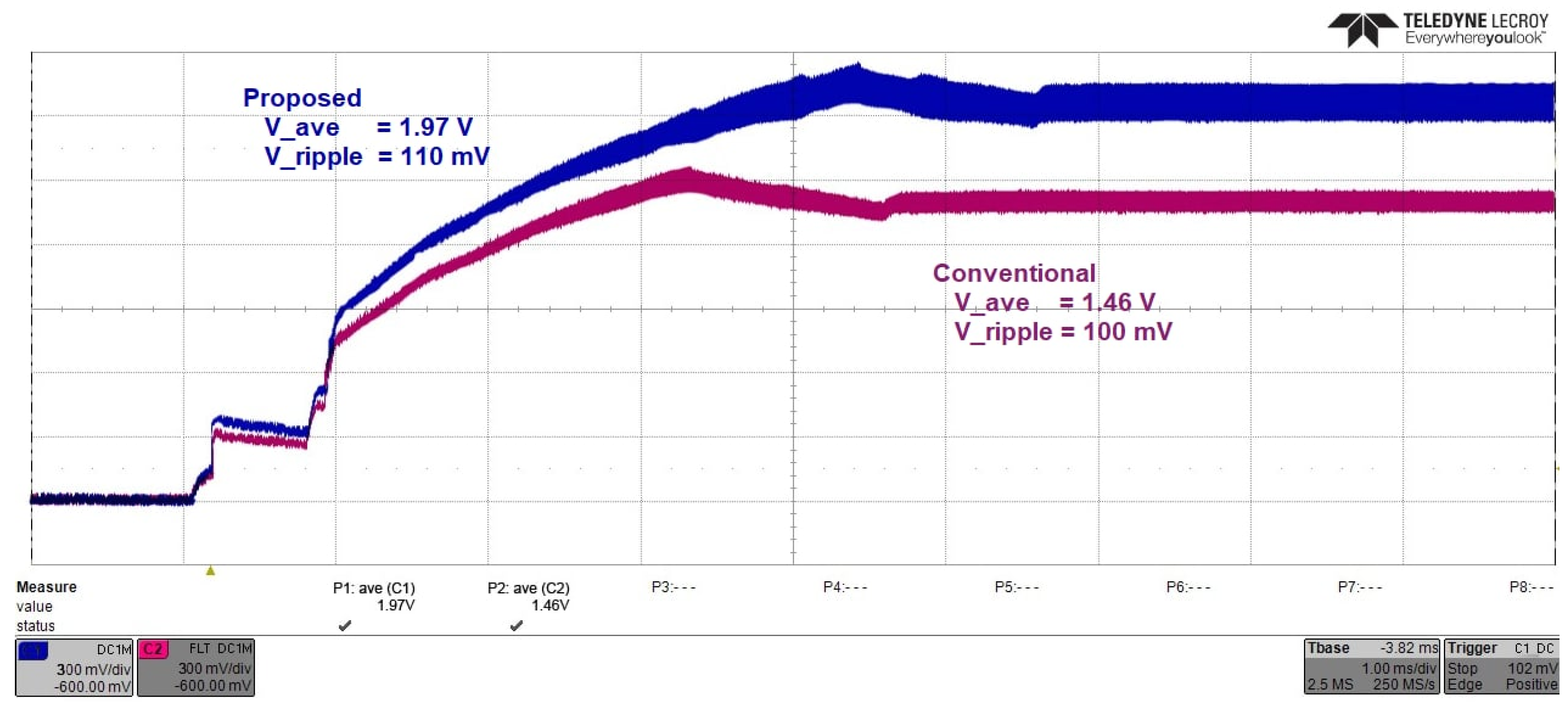

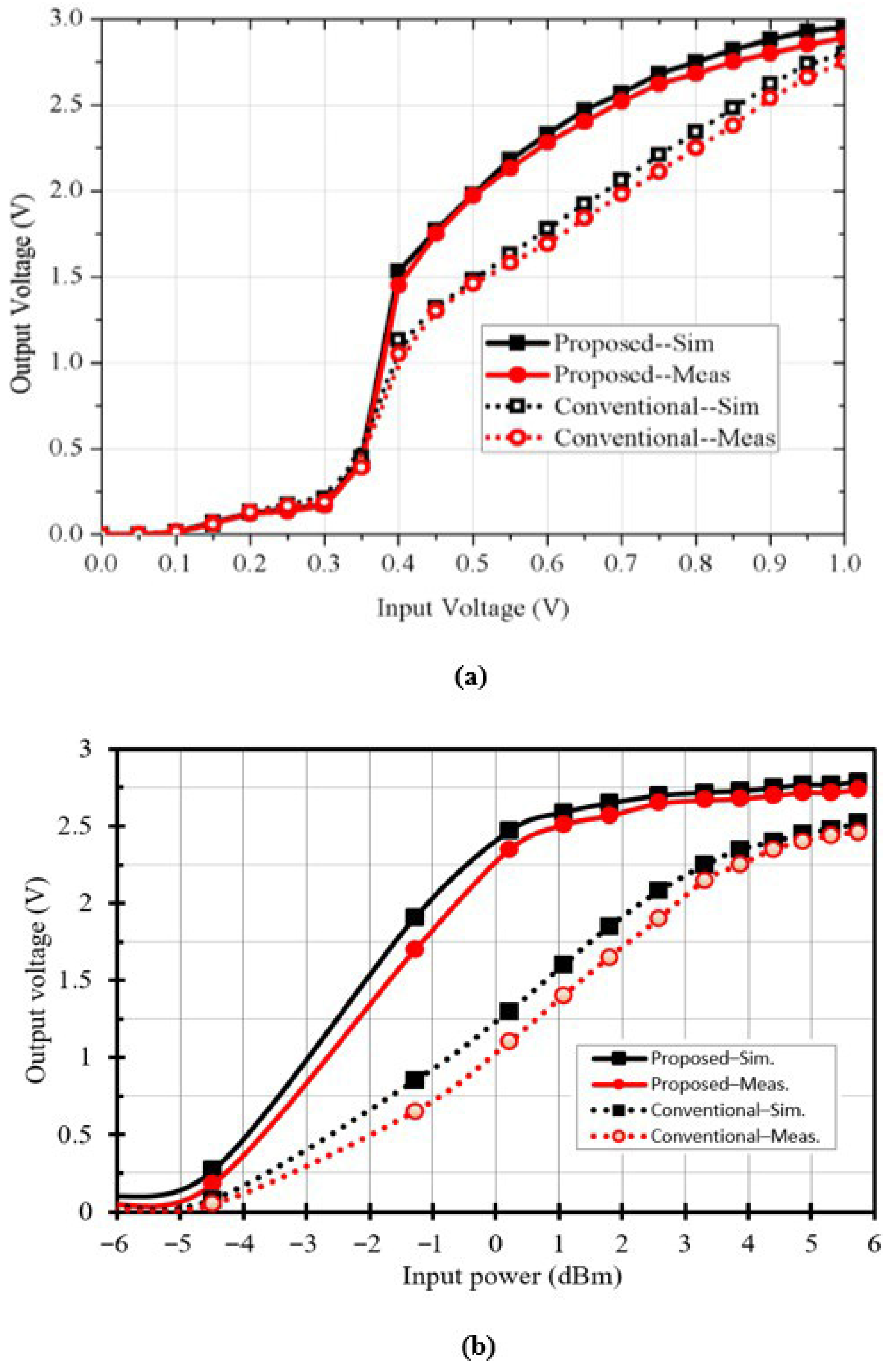

3.2. Measured Versus Simulated Output Waveforms

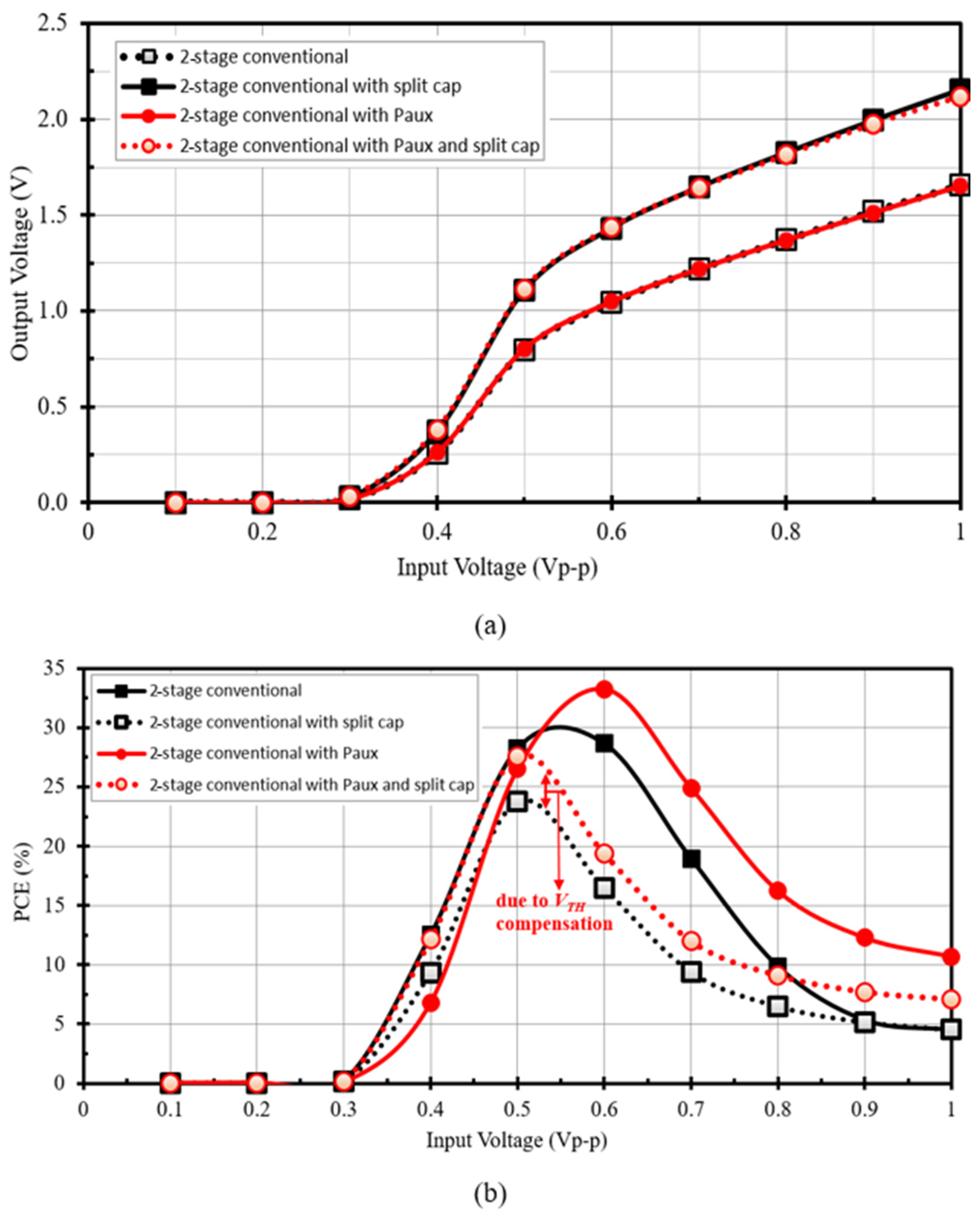

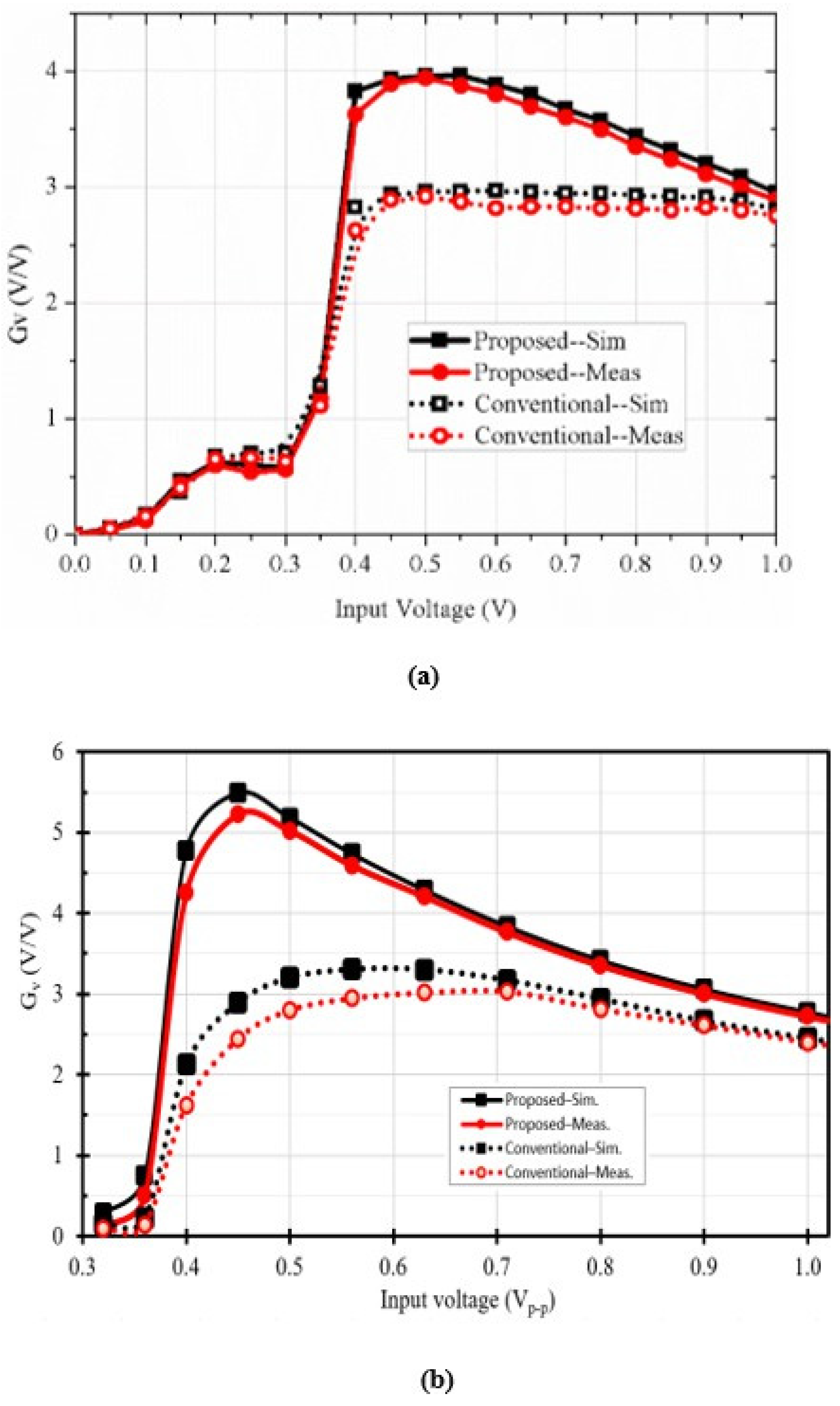

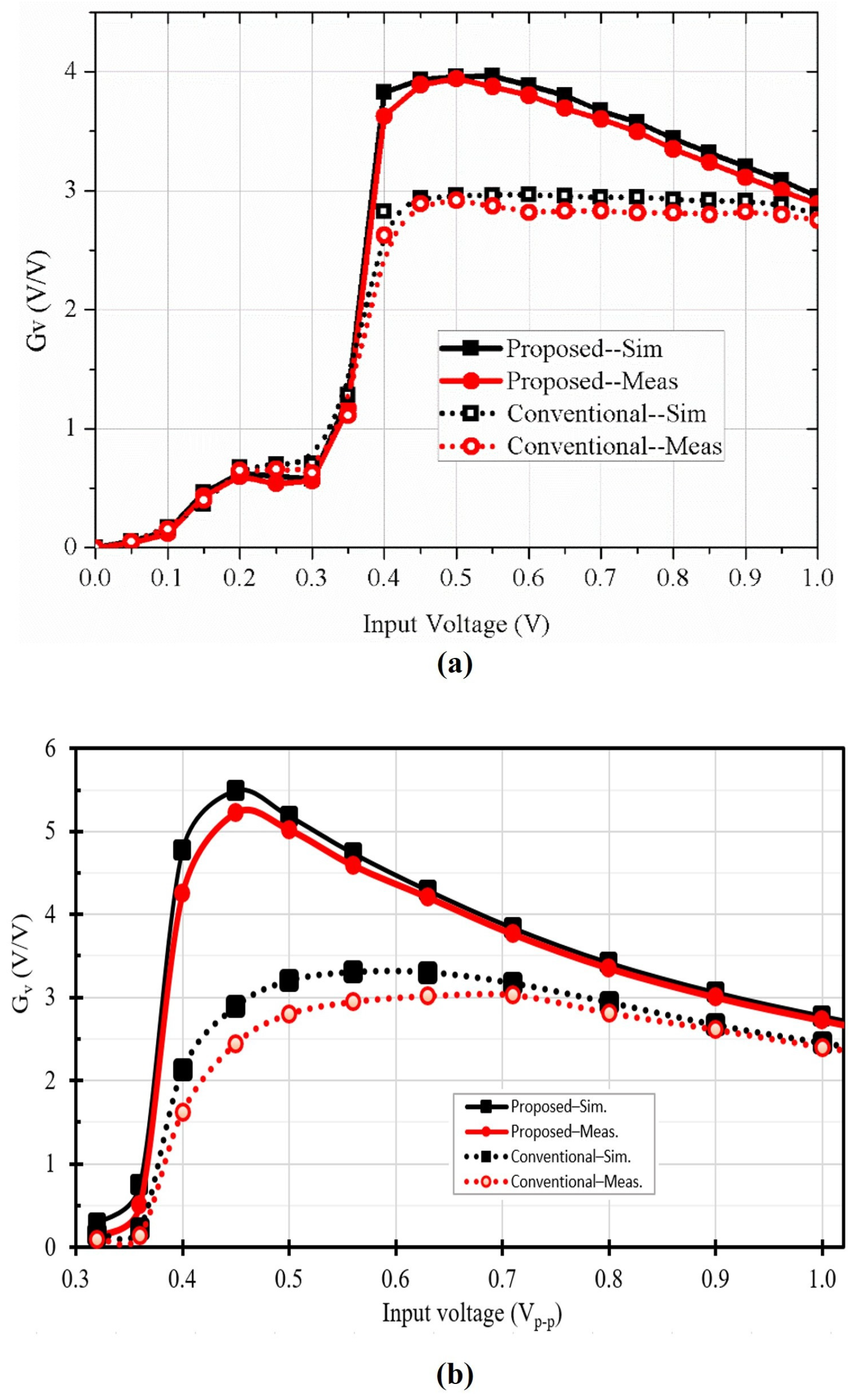

3.3. Voltage Conversion Ratio and Power Conversion Efficiency

3.4. Comparison with Previous Works

3.5. Dynamic Regulation and Energy Storage Integration

| Reference | Circuit | Operating | Input | Output | No. of | VCR | Peak | Load Current | CMOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Techniques | Frequency | Amplitude | Voltage | Stages | (V/V) | PCE (%) | RL, ILOAD | Tech. (µm) | |

| (V) | (V) | ||||||||

| DESIGN 1 [InLight EH] | |||||||||

| This work | Auxiliary MOS | 12.5 MHz | 0.5 | 1.97 | 3 | 3.94 | 58.7 | 2–8 mA | 0.065 |

| and Capacitor | |||||||||

| [23] Conventional, 2009 ° | Conventional | 12.5 MHz | 0.5 | 1.46 | 3 | 2.92 | 60.8 | 2–8 mA | 0.065 |

| [17] Chong, 2019 *a | CCDM *a Shared-capacitor | 12.5 MHz | 0.5 | 1.65 | 3 | 3.30 | b | 2–8 mA | 0.065 |

| coupling (ICC) *a | |||||||||

| [25] Grasso, 2019 *a | Body-voltage | 12.5 MHz | 0.5 | 1.55 | 3 | 3.10 | b | 2–8 mA | 0.065 |

| control scheme *a | |||||||||

| [36] Haddad, 2016 | Greinacher ULP | 13.56 MHz | 0.5 | 1.90 | 3 | 3.80 | 72 | 0.01 mA | 0.25 |

| [30] Guler, 2019 | Diode Reconfigurable | 13.56 MHz | 2.4 † | 4.92 † | 3 | 2.05 | 76 | 2 kΩ | 0.35 |

| VM | |||||||||

| DESIGN 2 [RF EH] | |||||||||

| This work | Auxiliary MOS | 2.4 GHz | 0.5 ‡ | 2.51 | 3 | 5.02 | 17.5 | 50 kΩ | 0.065 |

| and Capacitor | |||||||||

| [23] Conventional, 2009 ° | Conventional | 2.4 GHz | 0.5 ‡ | 1.39 | 3 | 2.80 | 19.7 | 50 kΩ | 0.065 |

| [17] Chong, 2019 *a | CCDM *a Shared-capacitor | 2.4 GHz | 0.5 ‡ | 2.20 | 3 | 4.44 | b | 50 kΩ | 0.065 |

| coupling (ICC) *a | |||||||||

| [25] Grasso, 2019 *a | Body-voltage | 2.4 GHz | 0.5 ‡ | 2.05 | 3 | 4.10 | b | 50 kΩ | 0.065 |

| [16] Moghaddam, 2017 | control scheme *a CCDM with Lower | 2 GHz | 0.5 ‡ | 2.48 † | 3 | 4.96 | 25 † | 50 kΩ | 0.13 |

| DC Feeding (LDCF) | |||||||||

| 2 GHz | 2.0 ‡ | 3.5 † | 1.75 | 65 † | 10 kΩ | ||||

| [31] Lau, 2017 | CCDM with DC-boosted | 2.45 GHz | 0.5 ‡ | 1.35 † | 2 | 2.7 | 48 † | 5 kΩ | 0.065 |

| gate bias | |||||||||

| 2.45 GHz | 0.159 ‡ | 1.04 † | 6.54 | 59.6 | 29 kΩ | ||||

| [20] Lo, 2017 | CCDM with HP Path | 900 MHz | 0.1 ‡ | 1.0 † | 5 | 10.0 | 36.5 | 147 kΩ | 0.065 |

| (LVTGP, LVTL_P) | |||||||||

| 900 MHz | 0.45 ‡ | 2.5 † | 5.55 | ||||||

| [32] Abouzied, 2017 | Reconfigurable Greinacher | 915 MHz | 0.5 ‡ | 2.35 † | 2 | 4.7 | 26 | 1 MΩ/PMU | 0.18 |

| doubler with LC matching | |||||||||

| 915 MHz | 0.5 ‡ | 2.35 † | 4 | 4.7 | 17.5 † | ||||

| 915 MHz | 0.079 ‡ | 1.0 † | 8 | 12.66 | 14 † |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hora, J.A.; Zhu, X.; Dutkiewicz, E. Design of High Voltage Output for CMOS Voltage Rectifier for Energy Harvesting Design. In Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Power Transfer Conference (WPTC), London, UK, 18–21 June 2019; pp. 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakiri, P.; Berthou, P.; Gokhale, A.; Abdellatif, S. Pubziesh/Subscribe-Enabled Software Defined Networking for Efficient and Scalable IoT Communications. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2015, 53, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandravee, B.; Caubel, J.J.; Kim, K.; Cheng, E.; Dhinakaran, A.; Agogino, A.M.; Martin, R.A. Sensor-Based Predictive Modeling for Smart Lighting in Grid-Integrated Buildings. IEEE Sens. J. 2014, 14, 4216–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Joe, I. Energy Management Algorithm for Solar-Powered Energy Harvesting Wireless Sensor Node for Internet of Things. IET Commun. 2016, 10, 1508–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prijić, A.; Vračar, L.; Pavlović, Z.; Kostić, L.; Prijić, Z. The Effect of Flat Panel Reflectors on Photovoltaic Energy Harvesting in Wire-less Sensor Nodes under Low Illumination Levels. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 7105–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoopman, M.; Philips, K.; Serdijn, W.A. An RF-Powered DLL-Based 2.4-GHz Transmitter for Autonomous Wireless Sensor Nodes. IEEE Trans. Microw. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2017, 65, 2399–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, V.; Lahuec, C.; Seguin, F.; Person, C. A Multi-Band Stacked RF Energy Harvester with RF-to-DC Efficiency up to 84%. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Technol. 2015, 63, 1768–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Wu, W. Cooperative Integration of RF Energy Harvesting and Dedicated WPT for Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 2019, 29, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Tan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Bergmann, N.W. Thermal Energy Harvesting WSNs Node for Temperature Monitoring in IIoT. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 35243–35249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaniam, S.; Baghaee, S.; Ulusam, H.; Zorlu, O.; Biyikoglu, E.-U.; Kulah, H. Implementation of Energy-Neutral Operation on Vibration Energy Harvesting WSN. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 3092–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Wei, R.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.; Leng, L.; Feng, P.-X.-L. An Ultralow Quiescent Current Power Management System with Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) for Batteryless Wireless Sensor Applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 7326–7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.E.; She, J.; Xue, J.; Kim, S.-H.; Park, C. LuxBeacon: A Batteryless Beacon for Green IoT: Design, Modeling, and Field Test. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 5901–5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Chew, K.W.R.; Tang, H.; Yu, G.; Siek, L. A 0.42-V Input Boost DC-DC Converter with Pseudo-Digital Pulsewidth Modulation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2014, 61, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhang, J.-J.; Wu, H.-H.; Tsu, T.; Wei, C.-L. Design of a Boost DC-DC Converter with 82-mV Startup Voltage and Fully Built-in Startup Circuits for Harvesting Thermoelectric Energy. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 2020, 3, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Sarpeshkar, R. Low-Power CMOS Rectifier Design for RFID Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2007, 54, 1177–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, A.K.; Chuah, J.H.; Ramiah, H.; Ahmadian, J.; Mak, P.I.; Martins, R.P. A 73.9%-Efficiency CMOS Rectifier Using a Lower DC Feeding (LDCF) Self-Body-Biasing Technique for Far-Field RF Energy-Harvesting Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2017, 64, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, G.; Ramiah, K.; Yin, J.; Rajendran, J.; Wong, W.R.; Mak, P.-I.; Martins, R.P. CMOS Cross-Coupled Differential-Drive Rectifier in Subthreshold Operation for Ambient RF Energy Harvesting: Model and Analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2019, 66, 1942–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, G.; Ramiah, H.; Yin, J.; Rajendran, J.; Wong, W.R.; Mak, P.-I.; Martins, R.P. A Wide-PCE-Dynamic-Range CMOS Cross-Coupled Differential-Drive Rectifier for Ambient RF Energy Harvesting. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2019, 68, 1743–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenta, C.R.; Durgin, G.D. Harvesting Wireless Power: Survey of Energy-Harvester Conversion Efficiency in Far-Field, Wireless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE Microw. Mag. 2014, 15, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shao, X.; Shahshahan, N.; Goldsman, N.; Salter, T.; Metze, G.M. An Antenna Co-Design Dual Band RF Energy Harvester. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2013, 60, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, H.; Yamazaki, D.; Yamamoto, T.; Kurata, H.; Yamada, S.; Mukaida, K.; Ninomiya, T.; Ohkawa, T.; Masui, S.; Gotoh, K. A Passive UHF RF Identification CMOS Tag IC Using Ferroelectric RAM in 0.35 µm Technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2007, 42, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-S.; Li, F.-B.; Zou, X.-C.; Liu, Y.; Hui, X.-M.; Tao, X.-F. New Analysis and Design of a RF Rectifier for RFID and Implantable. Sensors 2011, 11, 6494–6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, K.; Sasaki, A.; Ito, T. High-Efficiency Differential-Drive CMOS Rectifier for UHF RFIDs. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2009, 44, 3011–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, K.; Ito, T. High-Efficiency CMOS Rectifier Circuit with Self-VTH-Cancellation and Power Regulation Functions for UHF RFIDs. In Proceedings of the IEEE Asian Solid-State Circuits Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 12–14 November 2007; p. 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, L.; Sorbello, G.; Ragonese, E.; Palmisano, G. Codesign of Differential-Drive CMOS Rectifier and Inductively Coupled Antenna for RF Harvesting. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Technol. 2019, 68, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Dai, H.; Huang, M.-K.; Law, S.-W.; Sin, S.-P.U.; Martins, R.P. A Wide Input Range Dual-Path CMOS Rectifier for RF Energy Harvesting. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2017, 64, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Matters-Kammerer, M.; Milosevic, D.; Linnarts, J.-P.M.G.; Baltus, P. A Design of 2.4 GHz Rectifier in 65nm CMOS with 31% Efficiency. In Proceedings of the IEEE 20th Symposium on Communications and Vehicular Technology in the Benelux (SCVT), Namur, Belgium, 21 November 2013; 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Ki, W.-H.; Tsui, C.-Y. Analysis and Design Strategy of UHF Micro-Power CMOS Rectifiers for Micro-Sensor and RFID Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2007, 54, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hora, J.A.; Mayormita, M.A.; Rebolos, J.R.C.; Zhu, X.; Dutkiewicz, E. On-Chip Inductor-Less Indoor Light Energy Harvesting WSN/IoT Device Design. In Proceedings of the 2019 13th International Conference on Sensing Technology (ICST), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2–4 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, U.; Jia, Y.; Ghovanloo, M. A Reconfigurable Passive Voltage Multiplier for Wireless Mobile IoT Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2020, 67, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.Y.Y.; Siek, L. 2.45 GHz Wide Input Range CMOS Rectifier for RF Energy Harvesting. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Wireless Power Transfer Conference (WPTC), Taipei, Taiwan, 10–12 May 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzied, M.A.; Ravichandran, K.; Sanchez-Sinencio, E. A Fully Integrated Reconfigurable Self-Startup RF Energy-Harvesting System with Storage Capability. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2017, 52, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.-C.; Zou, H.-X.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Gao, Q.-H.; Yan, G.; Liu, F.-R.; Wei, K.-X.; Zhang, W.-M. Dynamically synergistic regulation mechanism for rotation energy harvesting. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 169, 108637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.-C.; Zou, H.-X.; Wei, K.-X.; Zhou, S.-X.; Meng, G.; Zhang, W.-M. Mechanical intelligent energy harvesting: From methodology to applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2300557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Fang, X. The real-time distributed control of shared energy storage for frequency regulation and renewable energy balancing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, P.-A.; Gosset, G.; Raskin, J.-P.; Flandre, D. Automated Design of a 13.56 MHz 19 µW Passive Rectifier with 72% Efficiency under 10 µA Load. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2016, 51, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|

| VIN | Input signal (peak amplitude) |

| VPP | Peak-to-peak input voltage |

| VDCN | DC output voltage at the final stage |

| VTH | Threshold voltage of MOS transistor |

| VDN, VDP | Voltage drops across NMOS and PMOS devices |

| VDROP | Total forward voltage drop, VDN + VDP |

| RDS_ON | ON-state drain–source resistance |

| CP, CS | Pumping and storage capacitors |

| Vaux | Auxiliary voltage generated by the PMOS-diode path |

| VCR | Voltage Conversion Ratio, VOUT/VIN |

| PCE | Power Conversion Efficiency, POUT,DC/PIN,AC |

| β | Transconductance parameter µCox(W/L) |

| m | Device multiplicity (number of parallel fingers) |

| N | Number of rectifier stages |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hora, J.; Palencia, G.F.; Sabarillo, R.; Tugahan, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, X. A Design of Rectifier with High-Voltage Conversion Gain in 65 nm CMOS Technology for Indoor Light and RF Energy Harvesting. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan14060117

Hora J, Palencia GF, Sabarillo R, Tugahan J, Sun Y, Zhu X. A Design of Rectifier with High-Voltage Conversion Gain in 65 nm CMOS Technology for Indoor Light and RF Energy Harvesting. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks. 2025; 14(6):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan14060117

Chicago/Turabian StyleHora, Jefferson, Gene Fe Palencia, Rochelle Sabarillo, Johnny Tugahan, Yichuang Sun, and Xi Zhu. 2025. "A Design of Rectifier with High-Voltage Conversion Gain in 65 nm CMOS Technology for Indoor Light and RF Energy Harvesting" Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks 14, no. 6: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan14060117

APA StyleHora, J., Palencia, G. F., Sabarillo, R., Tugahan, J., Sun, Y., & Zhu, X. (2025). A Design of Rectifier with High-Voltage Conversion Gain in 65 nm CMOS Technology for Indoor Light and RF Energy Harvesting. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks, 14(6), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan14060117