Ethnomedicinal Plant Knowledge of the Karen in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

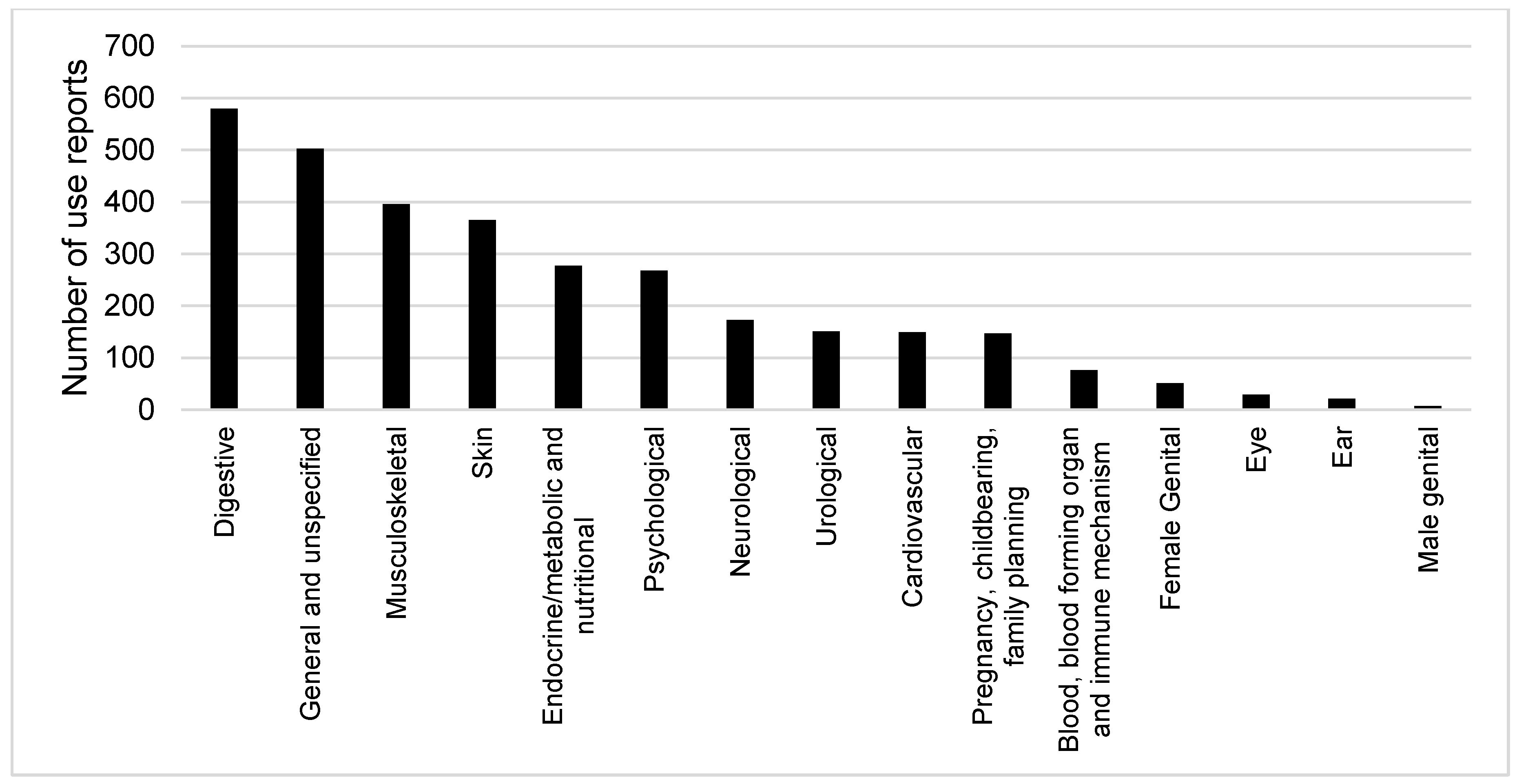

2.1. Ethnomedicinal Use Reports

2.2. Cultural Importance Index (CI)

2.3. Ethnomedicinal Use Categories

2.4. Informant Consensus Relating to Karen Ethnomedicinal Uses

3. Materials and Methods

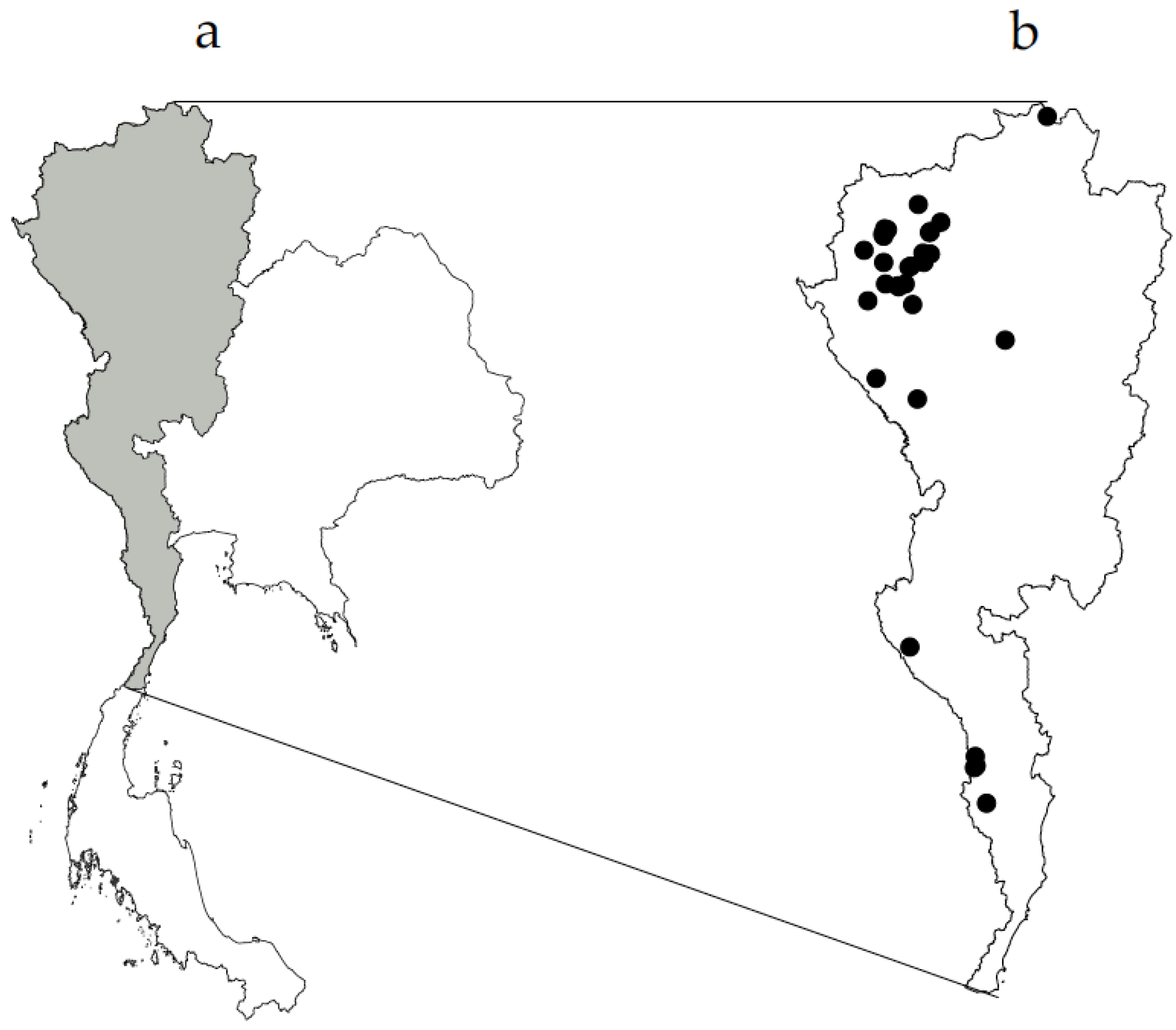

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Important Plant Taxa

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002–2005; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, P.A. Will Tribal Knowledge Survive the Millennium? Science 2000, 287, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricant, D.S.; Farnsworth, N.R. The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tu, Y. The discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and gifts from Chinese medicine. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srithi, K.; Balslev, H.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Srisanga, P.; Trisonthi, C. Medicinal plant knowledge and its erosion among the Mien (Yao) in northern Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 123, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voeks, R.A.; Leony, A. Forgetting the forest: Assessing medicinal plant erosion in Eastern Brazil. Econ. Bot. 2004, 58, S294–S306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragupathy, S.; Steven, N.G.; Maruthakkutti, M.; Velusamy, B.; Ul-Huda, M.M. Consensus of the ‘Malasars’ traditional aboriginal knowledge of medicinal plants in the Velliangiri holy hills, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooma, R.; Suddee, S. Tem Smitinand’s Thai Plant Names, Revised; The Office of the Forest Herbarium, Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Premsrirat, S. Ethnolinguistic Maps of Thailand; Ministry of Culture and Mahidol University: Bangkok, Thailand, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, T.H.P.-A.S. Mapping Human Genetic Diversity in Asia. Science 2009, 326, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisawat, B. Hill Tribes in Thailand; Pickanes Printing Center: Bangkok, Thailand, 2002; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sorasak Sanoprai, K.M. Karen. Available online: https://www.sac.or.th/databases/ethnic-groups/ethnicGroups/79 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Kamwong, K. Ethnobotany of Karens at Ban Mai Sawan and Ban Huay Pu Ling, Ban Luang Sub-District, Chom Thong District, Chiang Mai Province. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tipraqsa, P.; Schreinemachers, P. Agricultural commercialization of Karen Hill tribes in northern Thailand. Agric. Econ. 2009, 40, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyadee, P.; Balslev, H.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Inta, A. Karen Homegardens: Characteristics, Functions, and Species Diversity. Econ. Bot. 2018, 72, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewsangsai, K. Ethnobotany of Karen in Khun Tuen Noi Village, Mea Tuen Subdistrict, Omkoi Distric, Chiang Mai Province. Ph.D. Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Phumthum, M.; Sadgrove, J.N. High-Value Plant Species Used for the Treatment of “Fever” by the Karen Hill Tribe People. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangjitman, K.; Wongsawad, C.; Kamwong, K.; Sukkho, T.; Trisonthi, C. Ethnomedicinal plants used for digestive system disorders by the Karen of northern Thailand. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phumthum, M.; Balslev, H. Anti-Infectious Plants of the Thai Karen: A Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.F. Plants and People of the Golden Triangle: Ethnobotany of the Hill Tribes of Northern Thailand; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sukkho, T. A Survey of medicinal plants used by Karen people at Ban Chan and Chaem Luang Subdidtricts, Mae Chaem District, Chiang Mai Province. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Winijchaiyanan, P. Ethnobotany of Karen in Chiang Mai. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tangjitman, K.; Trisonthi, C.; Wongsawad, C.; Jitaree, S.; Svenning, J.-C. Potential impact of climatic change on medicinal plants used in the Karen women’s health care in northern Thailand. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 37, 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- Sutjaritjai, N.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Balslev, H.; Inta, A. Traditional Uses of Leguminosae among the Karen in Thailand. Plants 2019, 8, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumthum, M.; Balslev, H. Use of Medicinal Plants among Thai Ethnic Groups: A Comparison. Econ. Bot. 2019, 73, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumthum, M.; Srithi, K.; Inta, A.; Junsongduang, A.; Tangjitman, K.; Pongamornkul, W.; Trisonthi, C.; Balslev, H. Ethnomedicinal plant diversity in Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 214, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumthum, M. How far are we? Information from the three decades of ethnomedicinal studies in Thailand. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2020, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, R.B.G. State of the World’s Plants. 2017. Available online: https://stateoftheworldsplants.com (accessed on 14 July 2019).

- Phan, T.T.; Hughes, M.A.; Cherry, G.W. Enhanced proliferation of fibroblasts and endothelial cells treated with an extract of the leaves of Chromolaena odorata (Eupolin), an herbal remedy for treating wounds. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 101, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Jantan, I.; Bukhari, S.N.A. Tinospora crispa (L.) Hook. f. & Thomson: A Review of Its Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Aspects. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantasrila, R.; Pongamornkul, W.; Panyadee, P.; Inta, A. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used by Karen, Tak province in Thailand. Thai J. Bot. 2017, 9, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Srithi, K. Comparative Ethnobotany in Nan Province, Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G.P. Legumes of the World; Royal Botanic Gardens Kew: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Phumthum, M.; Balslev, H.; Barfod, A.S. Important Medicinal Plant Families in Thailand. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, F. Economic Botany Data Collection Standard Prepared for the International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases for Plant Sciences (TDWG); Royal Botanic Gardens: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Staub, P.O.; Geck, M.S.; Weckerle, C.S.; Casu, L.; Leonti, M. Classifying diseases and remedies in ethnomedicine and ethnopharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 174, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruca, M.; Cámara-Leret, R.; Macía, M.J.; Balslev, H. New categories for traditional medicine in the Economic Botany Data Collection Standard. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 1388–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Balslev, H.; Macía, M.J. Ethnobotanical knowledge is vastly under-documented in northwestern South America. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Cultural Importance Indices: A Comparative Analysis Based on the Useful Wild Plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain)1. Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, R.; Logan, M. Informant consensus: A new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In Plants in Indigenous Medicine and Diet: Biobehavioural Approaches; Etkin, N., Ed.; Redgrave Publishers: Bedford Hills, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

| Disorder Category | ICF |

|---|---|

| Ear | 0.50 |

| Musculoskeletal | 0.47 |

| Skin | 0.46 |

| Psychological | 0.45 |

| Blood, blood forming organ and immune mechanism | 0.44 |

| General and unspecified | 0.44 |

| Digestive | 0.42 |

| Urological | 0.40 |

| Pregnancy, childbearing, family planning | 0.38 |

| Endocrine/metabolic and nutritional | 0.35 |

| Eye | 0.29 |

| Neurological | 0.29 |

| Female Genital | 0.28 |

| Cardiovascular | 0.16 |

| Male genital | 0.00 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phumthum, M.; Balslev, H.; Kantasrila, R.; Kaewsangsai, S.; Inta, A. Ethnomedicinal Plant Knowledge of the Karen in Thailand. Plants 2020, 9, 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9070813

Phumthum M, Balslev H, Kantasrila R, Kaewsangsai S, Inta A. Ethnomedicinal Plant Knowledge of the Karen in Thailand. Plants. 2020; 9(7):813. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9070813

Chicago/Turabian StylePhumthum, Methee, Henrik Balslev, Rapeeporn Kantasrila, Sukhumaabhorn Kaewsangsai, and Angkhana Inta. 2020. "Ethnomedicinal Plant Knowledge of the Karen in Thailand" Plants 9, no. 7: 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9070813

APA StylePhumthum, M., Balslev, H., Kantasrila, R., Kaewsangsai, S., & Inta, A. (2020). Ethnomedicinal Plant Knowledge of the Karen in Thailand. Plants, 9(7), 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9070813