Abstract

The need to improve crop yield and quality, decrease the level of mineral fertilizers and pesticides/herbicides supply, and increase plants’ immunity are important topics of agriculture in the 21st century. In this respect, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) may be considered as a crucial tool in the development of a modern environmentally friendly agriculture. The efficiency of AMF application is connected to genetic peculiarities of plant and AMF species, soil characteristics and environmental factors, including biotic and abiotic stresses, temperature, and precipitation. Among vegetable crops, Allium species are particularly reactive to soil mycorrhiza, due to their less expanded root apparatus surface compared to most other species. Moreover, Allium crops are economically important and able to synthesize powerful anti-carcinogen compounds, such as selenomethyl selenocysteine and gamma-glutamyl selenomethyl selenocysteine, which highlights the importance of the present detailed discussion about the AMF use prospects to enhance Allium plant growth and development. This review reports the available information describing the AMF effects on the seasonal, inter-, and intra-species variations of yield, biochemical characteristics, and mineral composition of Allium species, with a special focus on the selenium accumulation both in ordinary conditions and under selenium supply.

Keywords:

onion; garlic; leek; shallot; AMF-related benefits; production; chlorophyll; antioxidants; mineral elements 1. Introduction

The beginning of the 21st century has been characterized by the intensive development of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) market, suggesting the great economic, ecological, and nutritional impact of this innovative agronomic approach [1]. The reports devoted to AMF application [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] have shown the crucial role of these fungi in the development of a sustainable modern agriculture, due to ability of AMF to significantly improve soil structure, nutrient and water availability, plant tolerance to drought, high temperature, salinity, heavy metals pollution and pathogens, and the stimulation of secondary metabolites synthesis resulting in higher crop quality.

AMF are beneficial microorganisms forming symbiotic relationships with most of terrestrial plant species, and their application has become a major farming practice in modern agriculture for increasing crop yield and product quality along with a concurrent decrease of mineral fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides utilization [9,10,11].

The efficiency of AMF utilization is connected to the AMF species, plant genotype, soil nutrient availability to plants, and environmental and stress factors [1]. Allium species are more sensitive to AMF application, compared to most other species, due to less developed root system [12,13,14,15,16].

Allium is considered one of the genera containing numerous species in plant kingdom, with more than 900 species, residing predominantly in the Northern Hemisphere. Many Allium representatives, such as garlic (Allium sativum), onion (A. cepa), leek (A. porrum), shallot (A. cepa L. Aggregatum group), chive (A. shoenoprasum), bunching onion (A. fistulosum) and others, are widely used in human nutrition [17]. Some other species are highly valuable as ornamental plants. All Allium species are rich in biologically active compounds, such as sulfur derivatives, quercetin, flavonoids, saponins, with significant anticancer, cardioprotective, anti-inflammation, antiobesity, antidiabetic, antioxidant, antimicrobial, neuroprotective, and immunomodulating effects [18]. Being secondary accumulators of selenium (Se), these plants express high tolerance to excess Se, synthesizing methylated forms of Se-containing amino acids and peptides, which are powerful anti-carcinogen agents [19].

Allium crops require high levels of N, P, and K and adequate water supply compared to other vegetables, because of weakly branched roots, causing low absorption levels of soil nutrients [20]. At the same time, high levels of nitrogen fertilizers may cause leaching, denitrification, and increase crop susceptibility to pests [21].

In this respect, the conventional practices based on massive fertilization, herbicide, and pesticide supply for production of Allium species [22,23] may be replaced to a large extent by the application of AMF, representing a technique for obtaining healthier products with no adverse environmental impact [9,10,24,25]. Accordingly, the exploitation of natural AMF–host potential is an important target in Allium crops.

The three following major factors support the AMF application for encouraging Allium plant growth and development:

- high economic importance of Allium crops in most world countries [17,18];

- the need to decrease the remarkable amount of mineral fertilizers and herbicides used in Allium crops’ production [20,26];

- the chance to increase selenium accumulation in Allium plants and to produce products with high concentration of natural anti-carcinogens [19].

However, the AMF application in Allium crop systems is not widespread yet, despite the potential benefits from this agricultural approach, due to the insufficient knowledge at farm level about the effective interactions between AMF and plants, and the difficulties to predict the consequent advantages [27]. Besides, information about the effect of AMF on Se accumulation in plants is rather limited, the results being often contradictory for different crops including singular representatives of Allium species [28,29].

Table 1 demonstrates separate examples of AMF application to Allium species’ growth and development. The presented approaches include the utilization of individual AMF strains and their combination, and interspecies variations of response to AMF inoculation focusing on few Allium representatives: A. cepa, A. sativum, A. roylei, A. fistulosum, A. porrum, A. galantum and A. cepa L. Aggregatum group. However, the investigations report different aspects from each other, relevant to AMF effect on Allium crops, which hampers the appropriate comparison between the results and consequent valuable conclusions. Nevertheless, the results presented are valuable in the introduction to this new technology.

Table 1.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) application on Allium species.

2. AMF Effect on Yield and Growth of Allium Species

Among different factors affecting the efficiency of AMF colonization [1,49,50], plant genotype and AMF species draw a special attention. Several studies have shown that most agricultural soils have a lower AMF species content compared to natural ecosystems. Furthermore, the beneficial effect of AMF to crop production with intensive fertilization is lower than that obtainable in the organic and low-input systems, due to the high soil nutrient availability (particularly phosphorus and nitrogen) in the former systems. The difference between natural and agricultural environment in AMF diversity may be connected to hyphal network disruption caused by tilling, inclusion of non-mycorrhizal species in crop rotation, use of fertilizers and fungicides, and fallow periods [51,52,53].

It is expected that large-scale production of Allium species entails the effect of a complex mixture of AMF species, which was confirmed in a large-scale investigation on organic and conventional onion systems in Netherlands, where 14 AMF phylotypes were identified [54]. The authors detected from one to six AMF phylotypes per field with the predominance of Glomus mosseae–G. coronatum and G. caledonium–G. geosporum species complexes, irrespective of cultivation system and sampled region [54]. The number of AMF phylotypes per field did not differ between organic and conventional farming systems. The authors demonstrated a positive correlation between onion yield and arbuscular and hyphal colonization (r = 0.70 and 0.85, respectively) under conventional management, and a lower correlation degree between arbuscular colonization and Ca content in soil (r = 0.55). AMF diversity did not affect onion yield both in organic and conventional farming.

A beneficial colonization of shallot roots by Glomus and Scutellospora, with a prevailing concentration of Glomus, was recorded by Priyadharsini et al. [42], whereas Mayr and Godoy [55] reported that vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae predominantly colonized the roots of Allium ursinum. A. porrum inoculation with Glomus mosseae, G. intraradices, and G. claroideum demonstrated the fastest roots’ colonization by Glomus mosseae and the lowest by G. claroideum [56]. On the other hand, A. porrum colonized by a mixture of G. claroideum and G. intraradices absorbed more P compared to the inoculation of the two single AMF. This phenomenon supposes the existence of synergism within the AMF community colonizing a single root system.

Other examples of AMF application [38,43] are consistent with the above observation. Notably, inoculation of A. porrum seedlings with Rhizophagus intraradices (RI), Claroideoglomus claroideum (CC), and Funneliformis mosseae (FM) resulted in significantly higher colonization level (59%) under the combinations RI + FM and RI + CC compared to single AMF species application. In an out-door pot-experiment on Allium cepa, a comparison was carried out between the effects of commercial AMF “Symbivit” preparation, containing a mixture of Glomus species (G. fasciculatum, G. mosseae, G. intraradices, G. etunicatum, G. microaggregatum, G. claroideum, and G. geosporum), a single AMF species (G. intraradices BEG140) application, and a combination of ‘Symbivit’ with saprotrophic fungi (Gymnopilus sp, Agrocybe praecox, and Marasmius androsaceus) [38]. ‘Symbivit’ application resulted in two-fold increase of onion yield compared to control, whereas a much lower effect was recorded upon the single G. intraradices inoculation. Furthermore, the authors stated the existence of synergism between AMF and saprotrophic fungi causing 50% increase of A. cepa yield in the presence of organic matter. Both the mentioned phenomena are remarkably important for environmentally friendly production systems.

Other investigations conducted both in greenhouse pot growing [34] and in open field [32] demonstrated small differences in the beneficial effect between G. versiforme and G. etunicatum on A. cepa (Azar-Shahr red onion) seedlings inoculated prior to transplant. The author recorded higher AMF beneficial effect on seedlings survival (27% in field conditions), three-fold bulb yield increase, significant improvement of water use efficiency, and leaf area enhancement compared to control plants.

Interestingly, wide significant differences in AMF response may take place between various Allium species [40,57]. Indeed, in Chechen republic field conditions, AMF-based formulate application (Rhyzotech plus) increased plant growth and yield by 1.4 and 1.45 times in A. cepa and A. sativum, respectively [57], whereas much higher interspecies differences were reported by Galvin et al. [40] in a pot experiment. In the latter research, G. intraradices inoculation to A. cepa, A. fistulosum, A. roylei, and two hybrids A. fistulosum x A. roylei, RF hybrid and A. cepa x (A. roylei x A. fistulosum) led to a higher increase of plant biomass and root length in A. fistulosum, compared to A. cepa, trihybrid, A. roylei, and A. fistulosum x A. roylei [40]; the lowest effect of AMF on yield was showed by RF hybrid and the highest by A. fistulosum. The authors reported wide differences in AMF beneficial effect between Allium species or hybrids in experiments carried out in pots of different size. Furthermore, Scholten et al.’s [41] reports showed the lower AMF beneficial effect on A. roylei yield compared to A. fistulosum and A. galanthum.

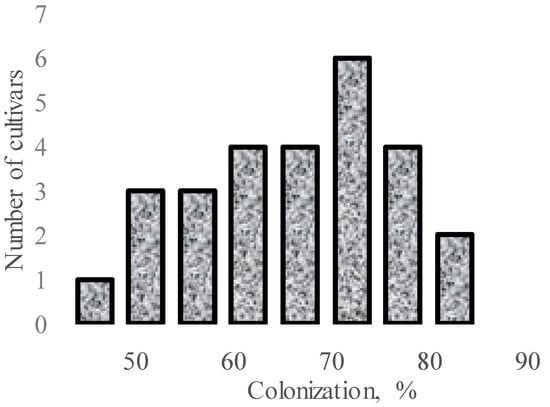

Significant varietal differences in AMF response may also take place among cultivars within Allium species. In this respect, investigations on 27 cultivars of A. fistulosum in greenhouse pot growing under Glomus fasciculatus inoculation revealed the significant mycorrhizal effect and the varietal differences in AMF response (Figure 1) [58]. This phenomenon was also previously recorded in other crops with better developed root systems, such as different cultivars of wheat [59], barley [60], and tomatoes [61]. Taking into account genetically determined differences of P accumulation in different cultivars, the authors suggest that the lower the ability of a cultivar to accumulate P, the higher the plant sensitivity to AMF [58].

Figure 1.

Varietal differences in A. fistulosum root colonization upon inoculation with G. fasciculatus (data re-elaborated from Tawaraya et al., 2001 [58]).

Similar to other agricultural crops, the colonization intensity of Allium depends on the soil P and N contents. Studies on Allium schoenoprasum inoculated with Glomus caledonium at three levels of P and N revealed that the best crop response to this fungus was recorded at the intermediate levels of P and N, whereas the lowest fungus infection occurred under high P and N levels [62]. Previous investigation [54] reported an 18-fold increase in leaves biomass of A. cepa under AMF application in P-deficient soils. Moreover, the seasonal effect of AMF inoculation to Allium is not usually significant [33].

3. Effects of AMF on Physiological, Quality, and Antioxidant Indicators in Allium Species

The enhancement of nutrient and water efficiency upon AMF inoculation leads to physiological and quality improvement of produce. In this respect, Bolandnasar et al. [34] demonstrated 30% increase in chlorophyll content of A. cepa leaves under AMF application, with no significant differences between the Glomus species tested. The joint application of the Glomus-containing formulate Symbivit and saprophyte fungi to A. cepa resulted in a remarkable increase of bulb’s antioxidant activity (AOA) [38]. The lowest increase of onion AOA was recorded under the G. intraradices BEG140 inoculation, where no significant differences in ascorbic acid accumulation were recorded between control and AMF-treated plants. The latter phenomenon may be connected with the low vitamin C concentration usually detected in onion bulbs. In this respect, the AOA increase in AMF-treated plants [38] is presumably related to the increase of phenolics and flavonoids, which are the main onion antioxidants, rather than to ascorbic acid. The inoculation of five different A. cepa cultivars with Glomus species (G. versiforme, G. intraradices, and G. mosseae) also revealed a significant increase in AOA with the highest beneficial effect caused by G. versiforme [30]. Field experiment in the Chechen republic (Russia) demonstrated a 32% increase in phenolics and 15% in AOA of A. cepa bulbs, but no significant effect on garlic antioxidant quality was found [57].

The antioxidant activity of Allium species is remarkably determined by the content of sulfur derivatives [63], showing high anticarcinogenic and cardioprotective effects [64]. Chemical and spectroscopic studies showed that in agricultural areas most of the soil sulfur is poorly available for plants and conversion of carbon-bonded sulfur to inorganic sulfates characterized by high assimilation levels is governed by the presence of soil microbes [65]. In this respect, AMF inoculation results in controversial effects on sulfur accumulation in Allium plants. Indeed, in a pot experiment mycorrhizal colonization of A. cepa roots with Glomus versiforme or Glomus intraradices BEG141 did not significantly affect bulb enzyme-produced pyruvate or sulfur accumulation levels in shoots, and a higher yield and N and P accumulation levels increase was elicited by G. versiforme inoculation [66]. Another investigation regarding N and S supply to A. fistulosum revealed that total and organic sulfur content in shoots and enzyme-produced pyruvate were significantly lower in case of Glomus mosseae utilization compared to control plants [67]; conversely, the same indicators attained higher or not different values in plants treated with Glomus intraradices compared to control. Moreover, Glomus fasciculatum application increased alliin content and alliinase activity in garlic [47].

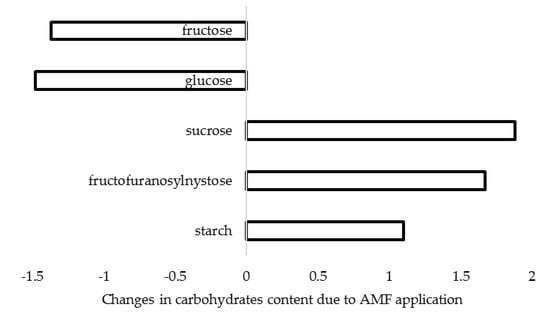

Salvioli et al. [68] reported that mycorrhizal colonization significantly impacts host gene expression and metabolomic profiles. Indeed, AMF inoculation is known to affect photosynthesis and the sugar metabolism [69], for instance, via stimulation of biosynthesis of phytohormones, such as abscisic acid [70]. In this respect, Glomus fasciculatum and G. mosseae application to A. sativum resulted in increased chlorophyll and sugar content in leaves [28]. Furthermore, Lone et al. [71] recorded significant changes in carbohydrates content of A. cepa bulbs treated with G. intraradices and G. mosseae, and in particular the decrease of monosaccharides (reducing sugars) and the increase of disaccharides and injectable oligosaccharides (Figure 2). Conversely, a 68% increase of monosaccharides content in A. cepa inoculated with mycorrhizal formulate Rhizotech Plus was reported in a field experiment [57].

Figure 2.

Changes in carbohydrate content in A. cepa bulbs as a result of G. intraradices and G. mosseae inoculation (data re-elaborated from Lone et al., 2015 [71]).

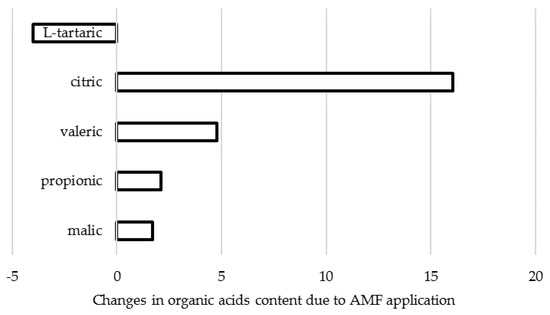

The biosynthesis of organic acids and sugar metabolism are known to be closely related. Indeed, titratable acidity (TA) increase upon AMF application was recorded in tomato [72]; in shallot [11] and onion [57,73] under open field double inoculation, with a 69% and 162% increase, respectively; in open field A. cepa treated with “Rhizotech Plus” formulate, with a 45% rise [57]. In research carried out in Poland, Rospadec et al. [74] reported the TA increase in A. cepa bulbs under Rhizophagus irregularis application (Figure 3), with significant changes in organic acids content from: malic > propionic > tartaric > valeric > citric before inoculation, to malic > propionic > citric > valeric > tartaric after inoculation.

Figure 3.

Changes in organic acids content in A. cepa cultivar Wolska upon AMF (Rhizophagus irregularis) inoculation (data re-elaborated from Rozpḁdek et al., 2016 [74]).

Organic acids are synthesized via oxidation of photosynthetic assimilates. Their biological functions include production of amino acids and ATP, maintenance of redox balance and membranes permeability, and acidification of extracellular spaces. Organic acids release by roots result in soil acidification, thus improving plant nutritional efficiency, including either phosphorous and iron accumulation or their transport across xylem [73]. The data shown in Figure 3 suggest the increase of total organic acid pool including malate and in particular, citrate in A. cepa bulbs under AMF application. The latter phenomenon may also be connected with the increase in nitrogen accumulation and has a beneficial effect on plant development, thanks to the participation of organic acids in energy and amino acids production.

4. Effects of AMF on Elemental Composition

AMF inoculation reportedly increases the accumulation of phosphorous, potassium, nitrogen, and several essential microelements, as a consequence of root system enhancement. Increase in N, P, and K content was detected in A. cepa upon the inoculation of AMF (Glomus sp. + Gigaspora) and sulfur oxidizing bacteria [36]. Inoculation of A. cepa plants with Glomus versiforme resulted in higher accumulation of N, P, and Zn compared to plants treated with Rhizophagus intraradices [75,76]. The mycorrhizal infected plants of A. cepa also showed a higher efficiency in nutrient and water uptake [77] and enhanced adaptation to different water accessibility in the soil [78]. According to Bolandnazar et al. [34], Glomus versiforme significantly enhanced the water use of A. cepa under water-deficit conditions [79]. Accordingly, the AMF-inoculated A. cepa plants demonstrated higher evapotranspiration, increased leaf area, biomass, and higher yield compared to control [21,34]. Investigations on A. cepa, cultivar “White Lisbon” [80] and A. cepa cv. Alfa São Francisco—Cycle VIII (Embrapa Semi-Árido) [37] demonstrated that joint application of humic substances and AMF (Glomus intraradices [80] and Rhizophagus intraradices [37]) synergistically increased growth and nitrogen and phosphorous levels [37,80], as well as protein content [37]. The interaction between humic substances and AMF also resulted in the highest accumulation of sugars and proteins in leaves, and consequently caused higher yield and quality of onion bulbs [37]. Other works indicate that AMF are able to secrete acid phosphatases, thus improving P accumulation [81]. AMF may affect the metals’ utilization by plants via element immobilization on their hyphae cell walls, chelating them by glomalin or via compartmentalization inside cells. Testing three commercial AMF formulates “Pla” (TerraVital Hortimex + G. mosseae, G. intraradices + G. claroideum + G. microaggregatum), “Bio” (Endorize-Mix + G. mosseae, G. intraradices), and “Tri” (G. mosseae + G. intraradices + G. etunicatum) in pot experiment with peat substrate containing from 20% to 40% of compost revealed significant increase of potassium and Zn content in A. porrum pseudostems compared to control plants. In the latter conditions, AMF colonization did not affect plant growth and P uptake, supposedly due to the lower availability of P organic forms to some AM fungi compared to inorganic P forms [46].

Expression of plant tolerance genes to different metals is known to greatly depend on the intensity of mycorrhizal colonization [5]. In this respect, a special attention should be focused to AMF effect on the accumulation of selenium, which is not considered an essential element for plant growth and development, though it shows significant antioxidant protective effects [66] and is a natural analog of sulfur, often replacing the latter element in biological systems [82].

5. Selenium–AMF Interaction

All Allium species belong to secondary selenium accumulators and are characterized by the ability to convert inorganic forms of soil selenium to methylated forms of Se-containing amino acids, such as selenomethyl selenocysteine and selenomethyl selenomethionine. This prevents the incorporation of such amino acids into proteins, contrary to plants non-accumulators where no methylated forms are synthesized and the transport of selenium to proteins causes the decrease of enzyme’s biological activity and accordingly toxicity [83]. Moreover, methylated Se containing amino acids are highly valuable for human health, thanks to their pronounced anti-carcinogenic properties [84,85]. In particular, the Se-analogs of the sulfur compounds in Allium, such as diallyl selenide and benzyl selenocyanate, were reportedly more effective as anticarcinogenic agents than diallyl sulfide and benzyl thiocyanate [86].

Up to date, a lot of investigations have been devoted to plant biofortification with Se, leading to products with high antioxidant activity and able to treat Se deficiency, which affects about 15% of the world population due to Se poor soils [87]. At the same time, plant enrichment with Se entails a serious ecological problem, taking into account that either soil or foliar Se supply shows low efficiency, thus resulting in a remarkable amount of unabsorbed Se with consequent environmental pollution; in addition, a significant fraction of soil Se is poorly available to plants.

Currently, plenty of papers report the involvement of soil microorganisms in redox biotransformation of Se [88], which causes the protection of plants against high concentrations of Se, thus improving the tolerance to selenium accumulation. However, the findings are controversial, as Patharajan and Raaman [28] suggested the depression of AMF sporulation in soil under selenium dioxide supply, whereas Larsen et al. [29] indicated the opposite effect on sodium selenate. Results on the effects of AMF inoculation on other species’ growth and development under Se supply are also controversial. Indeed, Duràn et al. [89] showed 23% increase in Se content in wheat upon the joint inoculation of Glomus claroideum and bacteria tolerant to Se (Stenotrophomona sp. B19, Enterobacter sp. B16, Bacillus sp. R12, and Pseudomonas sp. R8). On the other hand, AMF inoculation of several other agricultural crops, such as lettuce [90], maize, alfalfa, and soybean [91], reduced the Se content in plants. Similar controversies arose from studies focusing on AMF effect on accumulation of sulfur, which is a Se chemical analog [47,66,67,92].

Scant literature is available about the effect of AMF on the efficiency of Se biofortification in plants, especially in Allium species, as well as regarding the effect of different AMF species on the intensity of Se biofortification in Allium crops. Nevertheless, previous investigations suggest the interesting prospects of AMF utilization for improving Allium Se status. In this respect, Larsen et al. [29] demonstrated the chance of increasing garlic selenium content through soil inoculation with Glomus intraradices and of improving Se biofortification by joint application of AMF and sodium selenate, which enhances Se content from 1.5 to 15 mg·kg−1 d.w. The authors reported that the predominant form of Se in AMF + Se treated A. sativum was γ-glutamyl-Se-methyl-selenocystein, which represents more than two-thirds of total Se and is the compound with the highest anticarcinogenic effect [29].

A significant Se-AMF interaction was detected in shallot plants inoculated with Glomus-based formulate (“Rhisotech plus”) under organic (selenocystine) and inorganic (sodium selenate) Se supply [11]. The results suggest that AMF inoculation increased soil Se bioavailability in shallot plants by up to 8 times. A lower beneficial effect of AMF application was recorded under both organic and inorganic Se supply, i.e., the Se biofortification levels were increased by 5.9 and 4.4 times, respectively, compared to control plants. The organic Se form resulted in higher Se biofortification level than sodium selenate, both with and without AMF application [11].

The AMF beneficial effect on Se accumulation was also demonstrated in A. cepa and A. sativum grown in the same environmental conditions [57] (Table 2). Higher Se concentrations in fortified garlic bulbs grown with or without AMF inoculation reflect the higher ability of A. sativum to accumulate sulfur compared to A. cepa [93,94,95], which is consistent with the report that A. sativum is a more powerful natural anti-carcinogen than onion [85].

Table 2.

Effect of AMF–Se application on biochemical parameters and elemental composition of A. sativum and A. cepa (% to control plants) (data re-elaborated from Golubkina et al., 2020 [57]).

Overall, in the absence of exogenous Se, “Rhyzotech plus” AMF-based formulate inoculation increased Se content by 5 times in garlic, 10 times in onion, and 8 times in shallot bulbs [11,57]. Notably, contrary to A. sativum and A. cepa, shallot accumulated significantly lower levels of Se in conditions of joint Se and AMF application (not more than 5000 µg·kg−1 d.w.). In this respect, the results suggest that the efficiency of joint AMF + Se application on Se accumulation in the mentioned Allium representatives depended on the species and was the highest in A. sativum and decreased in A. cepa and shallot bulbs.

Interestingly, the effective AMF Se-fortification of garlic and onion leads to high prospects for producing functional food with the ability to significantly enhance the human Se status and, at the same time, to provide compounds with high anticarcinogen activity. According to Golubkina et al.’s [57] reports, 5 g of Se-fortified fresh garlic bulbs ensure 50% of the adequate Se consumption level (ACL is 70 mcg·day−1), whereas 50 g of Se-enriched onion bulbs will give as much as 1.4 ACL for Se.

Another aspect of Allium species biofortification with Se under AMF inoculation is the effect of joint Se-AMF application on biochemical characteristics and mineral content of the produce. Lacking literature reports for most crops makes these investigations extremely attractive. In this respect, the studies carried out on shallot, onion, and garlic under AMF-based formulate application revealed the following details [11,57]: the AMF beneficial effect on yield, carbohydrates, TA, and antioxidant content in the mentioned Allium species was enhanced by Se supply (Table 2). The data presented in Table 2 suggest that the joint Se–AMF application showed a higher beneficial effect than AMF inoculation on yield, monosaccharides, flavonoids, ascorbic acid, and AOA levels of A. cepa, the latter species attaining higher values compared to A. sativum. Moreover, among the antioxidants analyzed, an ascorbic acid increase in shallot bulbs [11] and A. sativum and A. cepa [57] was recorded in plants treated with AMF or sodium selenate (by 1.3 times compared to control plants in shallot bulbs [11], and lower levels in garlic and onion [57]; Table 2). Differently, the increase in flavonoids content was detected both in shallot plants inoculated with AMF or treated with AMF + selenocystine (by 1.44 and 1.33 times, respectively), whereas the highest increase in flavonoids content under AMF + Se application (1.7 times compared to the untreated control) was recorded in A. cepa bulbs. Notably, phenolics were not affected by the joint application of AMF and Se in A. sativum and just slightly in A. cepa.

Even wider differences between the effect of AMF and AMF + Se application were recorded for macro- and trace elements accumulation. Indeed, joint Se–AMF utilization stimulated the accumulation of K in onion and garlic bulbs and of Mg in onion. A phosphorus increase was detected only in garlic, whereas Ca content was much higher in plants inoculated with AMF without Se supply. Moreover, under Se + AMF application, a remarkable increase of B, Fe, Zn, and Si concentration was detected in A. cepa bulbs and of Zn and Fe in A. sativum.

The observed differences in sodium concentration due to AMF–Se applications (Table 2) may be attributed to the higher tolerance to salt stress of A. sativum compared to A. cepa [96] and the known relationship between Se and Na in plants [11].

One of the most significant effects of Se–AMF interaction seems to be the intensive increase in Mo accumulation both in A. cepa and A. sativum, which has never been reported previously. Notably, this element participates in plants redox reactions via Mo-containing enzymes including sulfite oxidase, xanthine dehydrogenase, nitrate reductase, and aldehyde oxidase, thus particularly taking part in nitrogen metabolism and phytohormones synthesis, including abscisic acid and indole-3 butylic acid. The latter fact may be of special importance as one of the possible mechanisms of Allium plants’ growth stimulation under joint application of Se and AMF.

Notably, results stemmed from investigations on shallot did not fully confirm the data presented in Table 2. In fact, the application of AMF-based formulate to shallot plants led to the increase of B (64.7%), Cu (47.4%), Fe (141%), Mn (77.9%), Zn (44.7%), and Si (78.4%) [11], whereas no differences in Cu and Mn accumulation between AMF and AMF + Se-treated A. sativum bulbs were recorded. Furthermore, shallot plants inoculated with AMF showed a reduced ability to accumulate Al, and this phenomenon was not reported for A. sativum and A. cepa [57]. The mentioned data suggest that the joint Se + AMF application may either not differ from that of AMF inoculation or even be more effective than the latter.

6. Conclusions

From the reports of the present review, three important aspects should be highlighted: (i) the inoculation of AMF species consortia usually provides higher beneficial effects than the single AMF species application, thus showing interesting utilization prospects within Allium crop systems; (ii) AMF application may become a new approach for producing functional food with high anticarcinogen activity, in interaction with Se biofortification of Allium species; (iii) the effect of AMF inoculation on mineral composition of Allium plants is species-dependent, and we have not found literature reports revealing these peculiarities, except for those relevant to N and P.

In general, the application of AMF to Allium species commonly grown as vegetables leads to significant enhancement of yield, physiological and quality indicators, antioxidant compounds and activity, and mineral content, in particular, selenium concentration. However, the effect of AMF on the mentioned crops greatly depends on plant genotype, AMF single species or species consortium, farming management, and soil and environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

N.G. and G.C. conceived the review topics and were involved in bibliographic search, as well as writing the draft and final version of the manuscript upon its critical revision. L.K., A.S. and V.V. contributed to bibliographic search and critical revision of the manuscript’s final version. A.T. was involved in bibliographic search and manuscript formatting. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, M.; Arato, M.; Borghi, L.; Nouri, E.; Reinhardt, D. Beneficial Services of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi—From Ecology to Application. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.G. Mycorrhizoremediation—An enhanced form of phytoremediation. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2006, 7, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A.; Batool, A.; Nasir, F.; Jiang, S.; Mingsen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, H. Mechanistic Insights into Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi-Mediated Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Song, F.; Liu, F. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Tolerance of Temperature Stress in Plants. In Arbuscular Mycorrhizas and Stress Tolerance of Plants; Wu, Q.-S., Ed.; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Singapore, 2017; pp. 163–194. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, N.; Qin, C.; Ahanger, M.A.; Raza, S.; Khan, M.I.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmed, N.; Zhang, L. Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Plant Growth Regulation: Implications in Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, C.V.T.; Araujo, K.E.C.; De Souza, S.R.; Schultz, N.; Júnior, O.J.S.; Sperandio, M.V.L.; Zilli, J. Édson Plant-mycorrhizal fungi interaction and response to inoculation with different growth-promoting fungi. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2019, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Berruti, A.; Lumini, E.; Balestrini, R.M.; Bianciotto, V. AMF as natural biofertilizers: Lets benefits from past successes. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Kingsley, K.L.; Zhang, Q.; Verma, R.; Obi, N.; Dvinskikh, S.; Elmore, M.T.; Verma, S.K.; Gond, S.K.; Kowalski, K.P. Review: Endophytic microbes and their potential applications in crop management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2558–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Golubkina, N.; Seredin, T.; Sellitto, B. Utilization of AMF in production of Allium species. Veg. Crop. Russ. 2018, 3, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Golubkina, N.A.; Caruso, G.; Vidican, R.; Sellitto, V.M.; Pietrantonio, L.D.; Martorana, M.E.; Lumini, E.F.; Balestrini, R. Effetto dei funghi micorrizici su fisiologia, produttività e qualità di cipolla, aglio e porro. Agrisicilia 2018, 4, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Golubkina, N.; Zamana, S.; Seredin, T.; Poluboyarinov, P.A.; Sokolov, S.; Baranova, H.; Krivenkov, L.; Pietrantonio, L.; Caruso, G. Effect of Selenium Biofortification and Beneficial Microorganism Inoculation on Yield, Quality and Antioxidant Properties of Shallot Bulbs. Plants 2019, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deressa, T.G.; Schenk, M.K. Contribution of roots and hyphae to phosphorus uptake of mycorrhizal onion (Allium cepaL.)-A mechanistic modeling approach. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2008, 171, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, D.J.F.; Mengel, K.; Kirkby, E.A. Principles of Plant Nutrition. J. Ecol. 1980, 68, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Gerwitz, A.; Stone, D.A.; Barnes, A. Root development of vegetable crops. Plant Soil 1982, 68, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, I.R.; Fitter, A. Evidence for differential responses between host-fungus combinations of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas from a grassland. Mycol. Res. 1992, 96, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bever, J.D.; Morton, J.B.; Antonovics, J.; Schultz, P.A. Host-Dependent Sporulation and Species Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in a Mown Grassland. J. Ecol. 1996, 84, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT 2015. Available online: http://faostat3.fao.org/browse/Q/QC/E (accessed on 8 August 2015).

- Zeng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Pu, X.; Du, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, T.; Yang, S. Therapeutic Role of Functional Components in Alliums for Preventive Chronic Disease in Human Being. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, S.; Kondo, M.; Chihara, Y.; Yuji, M.; Hattori, H.; Yoshida, M. Preparation of selenium-enriched sprouts and identification of their selenium species by high-performance liquid chromatography-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004, 68, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, J.L. Onions and Other Vegetable Alliums; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sekara, A.; Pokluda, R.; Del Vacchio, L.; Somma, S.; Caruso, G.; Agnieszka, S.; Robert, P.; Del, V.L.; Silvano, S.; Gianluca, C. Interactions among genotype, environment and agronomic practices on production and quality of storage onion (Allium cepa L.)—A review. Hortic. Sci. 2017, 44, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etana, M.B.; Aga, M.C.; Fufa, B.O. Major onion (Allium cepa L.) production challenges in Ethiopia: A review. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 2019, 9, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Suhardi, H.A. Effect of planting date and fungicide applications on the intensity of anthracnose on shallot. Indones. J. Hortic. 1996, 6, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, K.; Khalesro, S.; Sohrabi, Y.; Heidari, G.A. Review: Beneficial effects of the mycorrhizal fungi for plant growth. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. 2011, 1, 310–319. [Google Scholar]

- Plenchette, C.; Clermont-Dauphin, C.; Meynard, J.M.; Fortin, J.A. Managing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in cropping systems. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2005, 85, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.D.B. Agronomy of onions. In Allium Crop Science: Recent Advances; Rabinowitch, H.D., Currah, L., Eds.; CABI Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 187–232. [Google Scholar]

- Scullion, J.; Eason, W.; Scott, E. The effectivity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from high input conventional and organic grassland and grass-arable rotations. Plant Soil 1998, 204, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patharajan, S.; Raaman, N. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth and selenium uptake by garlic plants. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2012, 45, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, E.H.; Łobiński, R.; Burger-Meÿer, K.; Hansen, M.; Ruzik, L.; Mazurowska, L.; Rasmussen, P.H.; Sloth, J.J.; Scholten, O.; Kik, C. Uptake and speciation of selenium in garlic cultivated in soil amended with symbiotic fungi (mycorrhiza) and selenate. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 385, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollavali, M.; Bolandnazar, S.; Nazemieh, H.; Aliasgharzad, N. The effect of mycorrhizal fungi on antioxidant activity of various cultivars of onion (Allium cepa L.). Int. J. Biosci. 2015, 6, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kostin, M.; Podkovyrov, I. Using mycorrhiza in onion growing: Russian experience. GISAP Biol. Veter Med. Agric. Sci. 2017, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolandnazar, S. The effect of mycorrhizal fungi on onion (Allium cepa L.) growth and yield under three irrigation intervals at field condition. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2009, 7, 360–362. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, S.K.; Shinde, B.P. Consequence of arbuscular mycorrhiza on enhancement, growth and yield of onion (Allium cepa L.). Int. J. Life. Sci. Sci. Res. 2016, 2, 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bolandnazar, S.; Aliasgarzad, N.; Neishabury, M.; Chaparzadeh, N. Mycorrhizal colonization improves onion (Allium cepa L.) yield and water use efficiency under water deficit condition. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 114, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcón, R.; Tobar, R.M. Activity of nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase in shoot and root of mycorrhizal Allium cepa. Plant Sci. 1998, 133, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Eweda, W.E.; Heggo, A.; Hassan, E.A. Effect of dual inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and sulphur-oxidising bacteria on onion (Allium cepa L.) and maize (Zea mays L.) grown in sandy soil under green house conditions. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2014, 59, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettoni, M.M.; Mogor, Á.F.; Pauletti, V.; Goicoechea, N. Growth and metabolism of onion seedlings as affected by the application of humic substances, mycorrhizal inoculation and elevated CO2. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 180, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechtová, L.S.J.; Latr, A.; Nedorost, L.; Pokluda, R.; Posta, K.; Vosátka, M. Dual Inoculation with Mycorrhizal and Saprotrophic Fungi Applicable in Sustainable Cultivation Improves the Yield and Nutritive Value of Onion. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, B.; Azcon, C. Changes in the rhizospheric pH induced by arbuscular mycorrhiza formation in onion (Allium cepa L.). J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 1997, 160, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, G.A.; Kuyper, T.W.; Burger, K.; Keizer, L.C.P.; Hoekstra, R.F.; Kik, C.; Scholten, O.E. Genetic analysis of the interaction between Allium species and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 122, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, O.E.; Galvan-Vivero, G.; Burger-Meijer, B.J.; Kik, D.C. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi on growth and development of onion and wild relatives. In Proceedings of the Poster at: Joint Organic Congress, Odense, Denmark, 30–31 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Priyadharsini, P.; Pandey, R.; Muthukumar, T. Arbuscular mycorrhizal and dark septate fungal associations in shallot (Allium cepa L. var. aggregatum) under conventional agriculture. Acta Bot. Croat. 2012, 71, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučová, L.; Kopta, T.; Sekara, A.; Pokluda, R. Controlling Nitrate and Heavy Metals Content in Leeks (Allium porrum L.) Using Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculation. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 27, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučová, L.; Záhora, J.; Pokluda, R. Effect of mycorrhizal inoculation of leek Allium porrum L. on mineral nitrogen leaching. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 43, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Douds, J.D.D.; Boateng, A.A.; Douds, D.D. Effect of biochar soil-amendments on Allium porrum growth and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus colonization. J. Plant Nutr. 2015, 39, 1654–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, H.; Schwar, D.; George, E. Effect of mycorrhyzal inoculation and compost supply on growth and nutrient uptake of young leek plants grown on peat-based substrates. Hortic. Sci. 2006, 4, 628–632. [Google Scholar]

- Borde, M.; Dudhane, M.; Jite, P.K. Role of bioinoculant (AM Fungi) increasing in growth, flavor content and yield in Allium sativum L. under field condition. Not. Bot. Hortic. Agrobot. 2009, 37, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Karaki, G.N. Field response of garlic inoculated with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to phosphorus fertilization. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A. Fresh perspectives on the roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant nutrition and growth. Mycologia 2012, 104, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.C.; Graham, J.H.; Smith, F.A. Functioning of mycorrhizal associations along the mutualism-parasitism continuum. New Phytol. 1997, 135, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgason, T.; Daniell, T.; Husband, R.; Fitter, A.H.; Young, J.P.W. Ploughing up the wood-wide web? Nature 1998, 394, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniell, T.; Husband, R.; Fitter, A.H.; Young, J.P.W. Molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonizing arable crops. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2001, 36, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansa, J.; Mozafar, A.; Anken, T.; Ruh, R.; Sanders, I.; Frossard, E. Diversity and structure of AMF communities as affected by tillage in a temperate soil. Mycorrhiza 2002, 12, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Galván, G.A.; Parádi, I.; Burger, K.; Baar, J.; Kuyper, T.W.; Scholten, O.E.; Kik, C. Molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in onion roots from organic and conventional farming systems in the Netherlands. Mycorrhiza 2009, 19, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, R.; Godoy, R. Seasonal patterns in vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza in Melic-Beech Forest. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1990, 29, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansa, J.; Smith, F.A.; Smith, S.E. Are there benefits of simultaneous root colonization by different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi? New Phytol. 2008, 177, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkina, N.A.; Amagova, Z.; Matsadze, V.; Zamana, S.; Tallarita, A.; Caruso, G. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Yield, Biochemical Characteristics, and Elemental Composition of Garlic and Onion under Selenium Supply. Plants 2020, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawaraya, K.; Tokairin, K.; Wagatsuma, T. Dependence of Allium fistulosum cultivars on the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, Glomus fasciculatum. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2001, 17, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcon, R.; Ocampo, J.A. Factors affecting the vesicular-arbuscular infection and mycorrhizal dependency of thirteen wheat cultivars. New Phytol. 1981, 87, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baon, J.B.; Smith, S.E.; Alston, A.M. Mycorrhizal responses of barley cultivars differing in P efficiency. Plant Soil 1993, 157, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryla, D.; Koide, R.T. Role of mycorrhizal infection in the growth and reproduction of wild vs. cultivated plants. Oecologia 1990, 84, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bååth, E.; Spokes, J. The effect of added nitrogen and phosphorus on mycorrhizal growth response and infection in Allium schoenoprasum. Can. J. Bot. 1989, 67, 3227–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredotović, Ž.; Puizina, J. Edible Allium species: Chemical composition, biological activity and health effects. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2019, 31, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hanen, N.; Fattouch, S.; Ammar, E.; Neffati, M. Allium Species, Ancient Health Food for the Future; Chapter 17 in Scientific, Health and Social Aspects of the Food Industry; Valdez, B., Ed.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz, M. The role of soil microbes in plant sulphur nutrition. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1939–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, J.; Christie, P.; Li, X. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Ammonium: Nitrate Ratios on Growth and Pungency of Onion Seedlings. J. Plant Nutr. 2006, 29, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, J.; Christie, P.; Li, X. Influence of Nitrogen and Sulfur Fertilizers and Inoculation with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Yield and Pungency of Spring Onion. J. Plant Nutr. 2006, 29, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioli, A.; Bonfante, P. Systems biology and “omics” tools: A cooperation for next-generation mycorrhizal studies. Plant Sci. 2013, 203, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuab, R.; Lone, R.; Naidu, J.; Sharma, V.; Imtiyaz, S.; Koul, K.K. Benefits of inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth and development of onion (Allium cepa) plant. American-Eurasian. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2014, 14, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, F.; Baena-González, E.; Sheen, J. Sugar sensing and signaling in plants: Conserved and Novel Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Boil. 2006, 57, 675–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, R.; Shuab, R.; Wani, K.; Ganaie, M.A.; Tiwari, A.; Koul, K. Mycorrhizal influence on metabolites, indigestible oligosaccharides, mineral nutrition and phytochemical constituents in onion (Allium cepa L.) plant. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 193, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regvar, M.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Ševerkar, T. Effect of AMF inoculum from field isolates on the yield of green pepper, parsley, carrot, and tomato. Folia Geobot. Phytotaxon. 2003, 38, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igamberdiev, A.U.; Eprintsev, A.T. Organic Acids: The Pools of Fixed Carbon Involved in Redox Regulation and Energy Balance in Higher Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozpądek, P.; Rapala-Kozik, M.; Wężowicz, K.; Grandin, A.; Karlsson, S.; Ważny, R.; Anielska, T.; Turnau, K. Arbuscular mycorrhiza improves yield and nutritional properties of onion (Allium cepa). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 107, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, G.; Furlan, V.; Bernier-Cardou, M.; Doyon, G. Response of onion plants to arbuscular mycorrhizae. 1. Effects of inoculation method and phosphorus fertilization on biomass and bulb firmness. Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, G.; Furlan, V.; Bernier-Cardou, M.; Doyon, G. Response of onion plants to arbuscular mycorrhizae. 2. Effects of nitrogen fertilization on biomass and bulb firmness. Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E. Mycorrhizal Fungi Can Dominate Phosphate Supply to Plants Irrespective of Growth Responses. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosse, B.; Stribley, D.P.; LeTacon, F. Ecology of Mycorrhizae and Mycorrhizal Fungi. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 1981, 5, 137–210. [Google Scholar]

- Fitter, A.H. Functioning of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas under field conditions. New Phytol. 1985, 99, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linderman, R.; Davis, E. Vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhiza and Plant Growth Response to Soil Amendment with Composted Grape Pomace or Its Water Extract. HortTechnology 2001, 11, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Ezawa, T.; Cheng, W.; Tawaraya, K. Release of acid phosphatase from extraradical hyphae of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus clarus. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2015, 61, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkina, N.A.; Papazyan, T.T. Selenium in Food, Plants, Animals and Human Beings; Pechatny Gorod: Moscow, Russia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pilon-Smits, E.A.H. On the Ecology of Selenium Accumulation in Plants. Plants 2019, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Methylselenocysteine: A promising antiangiogenic agent for overcoming drug delivery barriers in solid malignancies for therapeutic synergy with anticancer drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, C.; Lisk, D.J. Enrichment of selenium in allium vegetables for cancer prevention. Carcinogenesis 1994, 15, 1881–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bayoumy, K.; Sinha, R.; Pinto, J.T.; Rivlin, R.S. Cancer Chemoprevention by Garlic and Garlic-Containing Sulfur and Selenium Compounds. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 864S–869S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather-Tait, S.J.; Bao, Y.; Broadley, M.R.; Collings, R.; Ford, D.; Hesketh, J.E.; Hurst, R. Selenium in Human Health and Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 1337–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Al-Khedhairy, A.; Ahamed, M.; Musarrat, J. Biomimetic Synthesis of Selenium Nanospheres by Bacterial Strain JS-11 and Its Role as a Biosensor for Nanotoxicity Assessment: A Novel Se-Bioassay. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, P.; Acuña, J.; Jorquera, M.; Azcón, R.; Borie, F.; Cornejo, P.; Mora, M.D.L.L. Enhanced selenium content in wheat grain by co-inoculation of selenobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: A preliminary study as a potential Se biofortification strategy. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 57, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín, C.; Garmendia, I.; Romano, B.; Díaz, M.; Palop, J.A.; Goicoechea, N. Mycorrhizal inoculation affected growth, mineral composition, proteins and sugars in lettuces biofortified with organic or inorganic selenocompounds. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 180, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yü, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wen, B.; Huang, H.; Luo, L. Accumulation and Speciation of Selenium in Plants as Affected by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Glomus mosseae. Boil. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 143, 1789–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, S.; Pérez-Labrada, F.; García-Enciso, E.L.; Leija-Martínez, P.; Medrano-Macías, J.; Dávila-Rangel, I.E.; Juárez-Maldonado, A.; Rivas-Martínez, E.N.; Benavides-Mendoza, A. Selenium and sulfur to produce Allium functional crops. Molecules 2017, 22, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minard, H.R.G. Effect of clove size, spacing, fertilisers, and lime on yield and nutrient content of garlic (Allium sativum). N. Z. J. Exp. Agric. 1978, 6, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randle, W.M.; Kopsell, D.E.; Kopsell, D.A.; Snyder, R.L. Total sulfur and sulfate accumulation in onion is affected by sulfur fertility. J. Plant Nutr. 1999, 22, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, E.; Haneklaus, S.; Schnug, E. Influence of Nitrogen and Sulfur Fertilization on the Alliin Content of Onions and Garlic. J. Plant Nutr. 2004, 27, 1827–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.; Grieve, C. Tolerance of vegetable crops to salinity. Sci. Hortic. 1998, 78, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).