Preliminary Automated Determination of Edibility of Alternative Foods: Non-Targeted Screening for Toxins in Red Maple Leaf Concentrate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Leaf Selection

2.1.2. Processing Chemicals

2.2. Material Processing

2.2.1. Leaf Concentrate

2.2.2. Sample Preparation

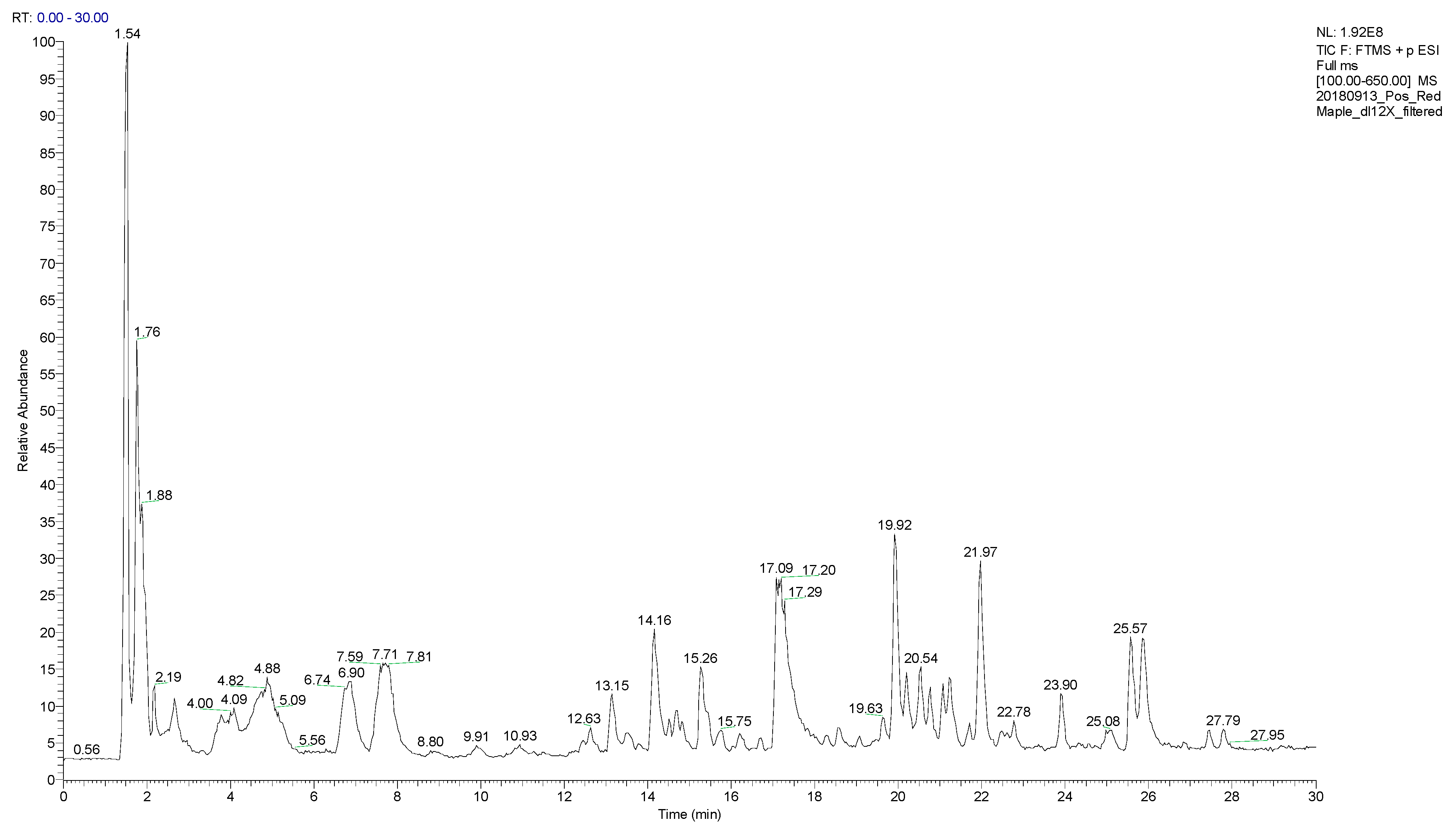

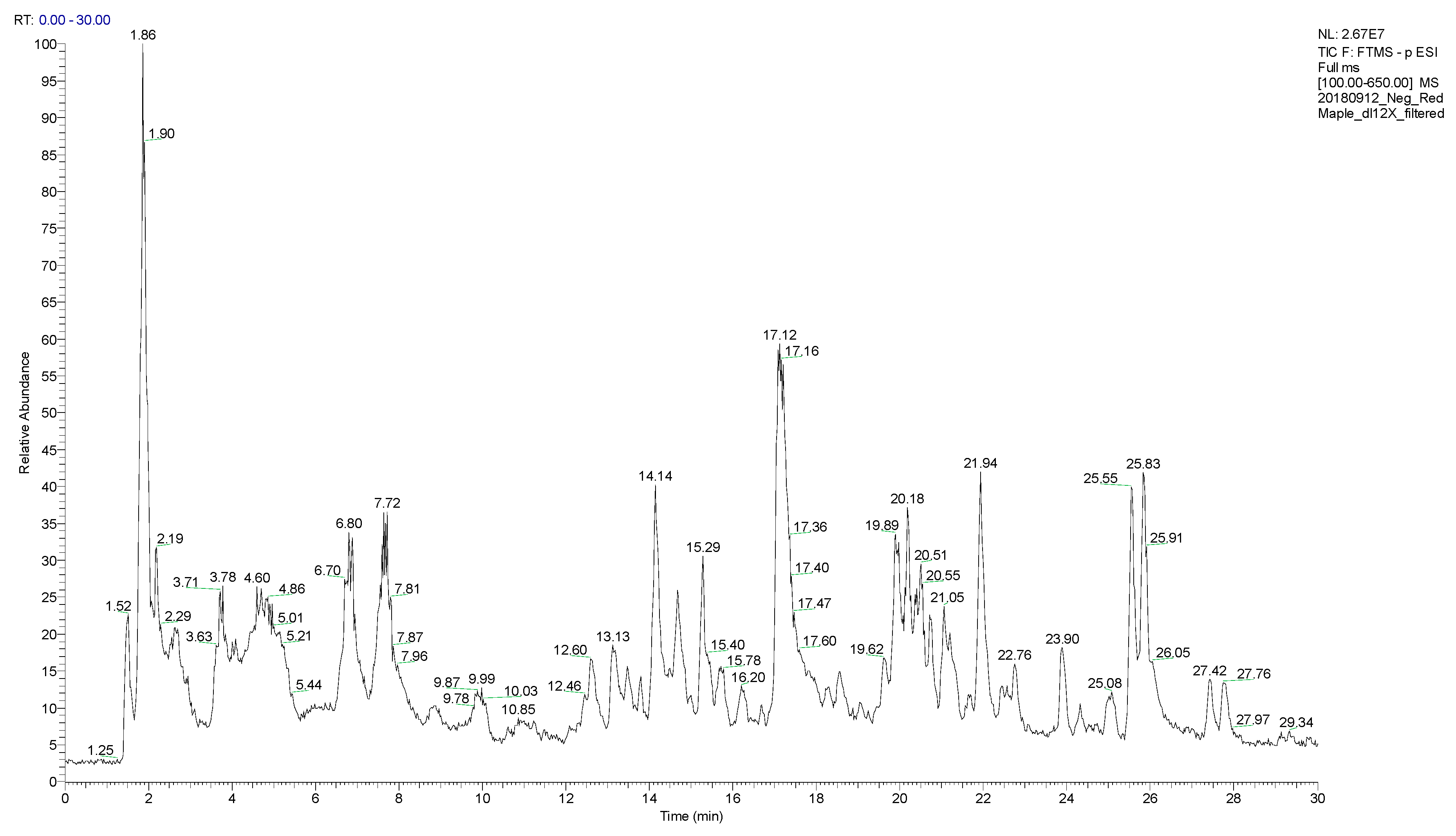

2.3. LC/MS Instrumentation

2.4. Data Analysis

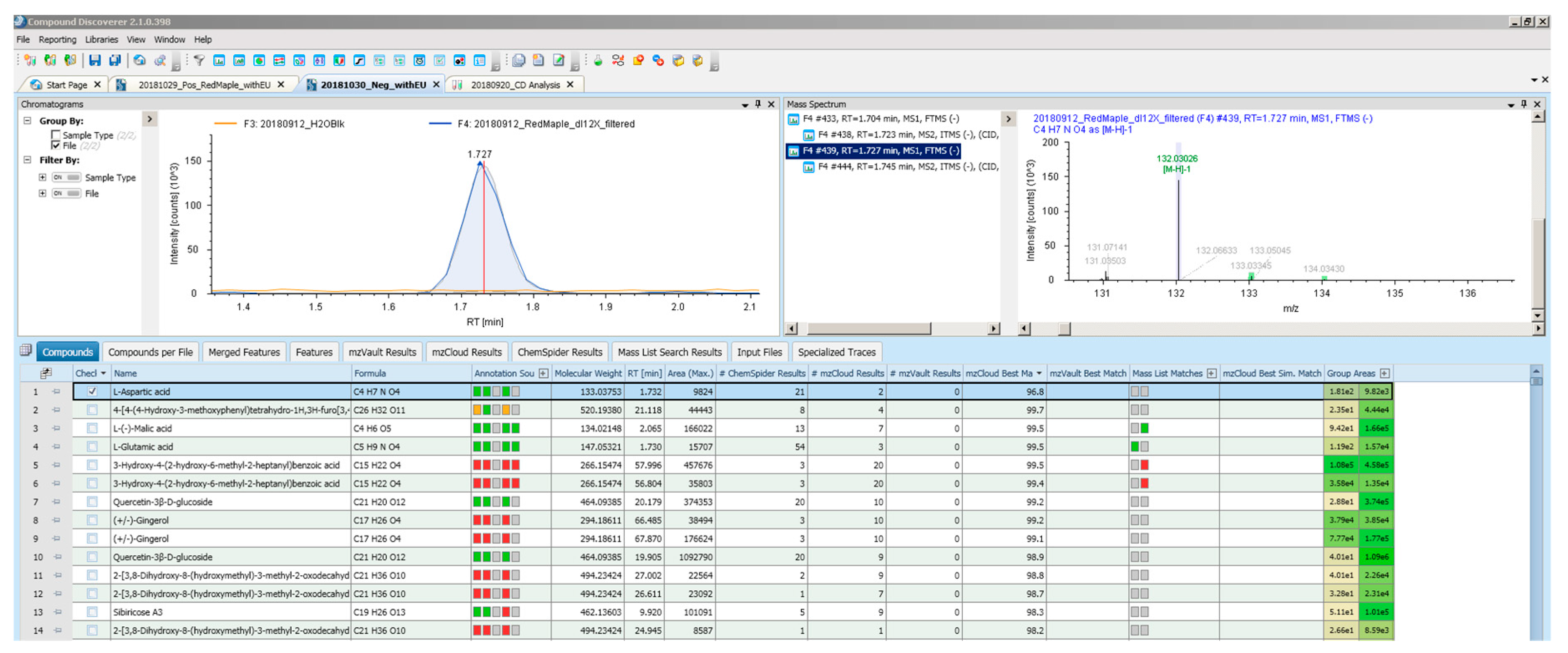

- Checked to make sure that the compound is only present in the sample and not in the blank (see the extracted ion chromatogram on the top left of Appendix A).

- Checked that the chromatographic peak is above the noise level. A signal to noise ratio (S/N) of 3 was used in the software and a minimum peak area of 1000 considered to validate the chromatography peaks from the noise.

- Checked that the chromatographic peak shape is good. This is done by looking at the extracted ion chromatogram generated by Compound Discoverer software for each compound to ensure that the chromatography peak shape is reliable.

- Checked the isotopic pattern. After Compound Discoverer assigns a chemical formula to the measured masses, it generates color-coded isotopic patterns on the mass spectrum of each compound (see the example mass spectrum associated with L-Aspartic acid on the top right of the Figure A1 in Appendix A).

- Compound Discoverer software searched ChemSpider databases for possible chemical structures for each assigned formula. The number of chemical structures found in ChemSpider that match the measured mass with the defined ppm mass error (3 ppm) is recorded.

- Compound Discoverer also searched a mass list developed by Thermo Scientific for leachable and extractable compounds.

- Finally, MS/MS mzCloud match is determined. With the LC/MS analysis, rather than the full scan mode, the data-dependent MS/MS fragmentation was collected on the 5 tallest peaks on the spectra. Compound Discoverer uses this information to match the fragmentation pattern with the mzCloud database. This adds another level of confidence for identification of unknown compounds.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Do Toxic Compounds Prevent Maple Leaf Concentrate Use as a Food?

4.2. Limitations and the Need for Open Source Collaboration

4.3. Alternative Food in Today’s Non-Disaster Context

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Denkenberger, D.C.; Pearce, J.M. Feeding everyone: Solving the food crisis in event of global catastrophes that kill crops or obscure the sun. Futures 2015, 72, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robock, A.; Oman, L.; Stenchikov, G.L. Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S.D. Confronting the threat of nuclear winter. Futures 2015, 72, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, M.E. Risk Analysis of Nuclear Deterrence. Bent Tau Beta Pi 2008, 99, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, A.M.; Seth, D.; Baum, S.D.; Hostetler, K. Analyzing and reducing the risks of inadvertent nuclear war between the United States and Russia. Sci. Glob. Secur. 2013, 21, 106–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M.; Denkenberger, D.C. A National Pragmatic Safety Limit for Nuclear Weapon Quantities. Safety 2018, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robock, A.; Toon, O.B. Local Nuclear War, Global Suffering. Sci. Am. 2010, 302, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.J.; Toon, O.B.; Turco, R.P.; Kinnison, D.E.; Garcia, R.R. Massive global ozone loss predicted following regional nuclear conflict. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5307–5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robock, A.; Toon, O.B. Self-assured destruction: The climate impacts of nuclear war. Bull. Atomic Sci. 2012, 68, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toon, O.B.; Robock, A.; Turco, R.P. Environmental consequences of nuclear war. AIP Conf. Proc. 2014, 1596, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S.D. Uncertain human consequences in asteroid risk analysis and the global catastrophe threshold. Nat. Hazards 2018, 94, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhall, C.; Self, S.; Robock, A. Anticipating future Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) 7 eruptions and their chilling impacts. Geosphere 2018, 14, 572–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, A.; Oppenheimer, C. Imagining the Unimaginable: Communicating Extreme Volcanic Risk. In Observing the Volcano World: Volcano Crisis Communication; Fearnley, C.J., Bird, D.K., Haynes, K., McGuire, W.J., Jolly, G., Eds.; Advances in Volcanology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 149–163. ISBN 978-3-319-44097-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom, N.; Cirkovic, M.M. Global Catastrophic Risks; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Valdes, P. Built for stability. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, J.P.; Woodford, M.H. Bioweapons, Biodiversity, and Ecocide: Potential Effects of Biological Weapons on Biological Diversity Bioweapon disease outbreaks could cause the extinction of endangered wildlife species, the erosion of genetic diversity in domesticated plants and animals, the destruction of traditional human livelihoods, and the extirpation of indigenous cultures. BioScience 2002, 52, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.C. Genetic Engineers Aim to Soup up Crop Photosynthesis. Science 1999, 283, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigo, H. Agricultural Biotechnology and the Negotiation of the Biosafety Protocol. Geo. Int’l Envtl. L. Rev. 1999, 12, 779. [Google Scholar]

- Church, G. Safeguarding biology. Seed 2009, 20, 84–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R.; Benton, T.G.; Challinor, A.; Elliott, J.; Gustafson, D.; Hiller, B.; Jones, A.; Kent, A.; Lewis, K.; Meacham, T.; et al. Extreme Weather and Resilience of the Global Food System: Final Project Report from the UK-US Taskforce on Extreme Weather and Global Food System Resilience; The Global Food Security Programme; Foreign & Commonwealth Office: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, S. High impact, low probability? An empirical analysis of risk in the economics of climate change. Clim. Change 2011, 108, 519–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizen, M.A.; Garibaldi, L.A.; Cunningham, S.A.; Klein, A.M. How much does agriculture depend on pollinators? Lessons from long-term trends in crop production. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, E.J. Drought, War, and the Politics of Famine in Ethiopia and Eritrea. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 1992, 30, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, R.J. Public Health in Times of War and Famine: What Can Be Done? What Should Be Done? JAMA 2001, 286, 588–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhand, J. Enduring Disorder and Persistent Poverty: A Review of the Linkages between War and Chronic Poverty. World Dev. 2003, 31, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avin, S.; Wintle, B.C.; Weitzdörfer, J.; Ó hÉigeartaigh, S.S.; Sutherland, W.J.; Rees, M.J. Classifying global catastrophic risks. Futures 2018, 102, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchin, A. Approaches to the Prevention of Global Catastrophic Risks. Hum. Prospect 2018, 7, 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Denkenberger, D.C.; Blair, R.W. Interventions that may prevent or mollify supervolcanic eruptions. Futures 2018, 102, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, A. Human Extinction from Natural Hazard Events. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Nat. Hazard Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchin, A.; Denkenberger, D. Global catastrophic and existential risks communication scale. Futures 2018, 102, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S.; Denkenberger, D.; Pearce, J.M. Alternative Foods as a Solution to Global Food Supply Catastrophes. Solutions 2016, 7, 31–35. Available online: https://www.thesolutionsjournal.com/article/alternative-foods-solution-global-food-supply-catastrophes/ (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Denkenberger, D.; Pearce, J.M. Feeding Everyone No Matter What: Managing Food Security After Global Catastrophe; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-12-802358-7. [Google Scholar]

- Denkenberger, D.; Pearce, J. Micronutrient Availability in Alternative Foods during Agricultural Catastrophes. Agriculture 2018, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkin, A. Micronutrients in health and disease. Postgrad. Med. J. 2006, 82, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkenberger, D.C.; Pearce, J.M. Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions for Alternate Food to Address Agricultural Catastrophes Globally. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2016, 7, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkenberger, D.C.; Pearce, J.M. Cost-effectiveness of interventions for alternate food in the United States to address agricultural catastrophes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S.D.; Denkenberger, D.C.; Pearce, J.M.; Robock, A.; Winkler, R. Resilience to global food supply catastrophes. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2015, 35, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkenberger, D.C.; Cole, D.D.; Abdelkhaliq, M.; Griswold, M.; Hundley, A.B.; Pearce, J.M. Feeding everyone if the sun is obscured and industry is disabled. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkenberger, D.; Pearce, J.; Taylor, A.R.; Black, R. Food without sun: Price and life-saving potential. Foresight 2018, 21, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekell, D.; Carr, J.; Dell’Angelo, J.; D’Odorico, P.; Fader, M.; Gephart, J.; Matti, K.; Magliocca, N.; Porkka, M.; Puma, M.; et al. Resilience in the global food system. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 025010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitz, H.D.; Grosch, W.; Schieberle, P. 2009 Food Chemistry; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-Y.; Chung, H.-J. Flavor Compounds of Pine Sprout Tea and Pine Needle Tea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf for Life. Industrial Leaf Concentrate Process (France). Available online: https://www.leafforlife.org/PAGES/INDUSTRI.HTM (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- Kennedy, D. Leaf Concentrate: A Field Guide for Small Scale Programs; Leaf for Life: Interlachen, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Singer, H.P.; Slobodnik, J.; Ipolyi, I.M.; Oswald, P.; Krauss, M.; Schulze, T.; Haglund, P.; Letzel, T.; Grosse, S.; et al. Non-target screening with high-resolution mass spectrometry: Critical review using a collaborative trial on water analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 6237–6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agroscope Toxic Plants-Phytotoxin (TPPT) Database. Available online: https://www.agroscope.admin.ch/agroscope/en/home/publikationen/apps/tppt.html (accessed on 3 December 2018).

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.-M.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis. Metabol. 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States. Forest Service Check List of Native and Naturalized Trees of The United States Including Alaska. 1953. Available online: https://archive.org/details/CheckListOfNativeAndNaturalizedTreesOfTheUnitedStatesIncludingAlaska (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- Forest Inventory and Analysis National Program-National Assessment-RPA. Available online: https://www.fia.fs.fed.us/program-features/rpa/index.php (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- Johansson, M.; Ekroth, S.; Scheibner, O.; Bromirski, M. How to screen and identify unexpected and unwanted compounds in food, Thermo Scientific: APPLICATION NOTE 65144. Available online: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/CMD/Application-Notes/an-65144-lc-ms-unexpected-unwanted-compounds-food-an65144-en.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- Great Big Story. 2018. When in Japan, Deep-Fry Some Maple Leaves. Available online: https://youtu.be/9Pwy-cAf09I (accessed on 8 January 2019).

- Alward, A.; Corriher, C.A.; Barton, M.H.; Sellon, D.C.; Blikslager, A.T.; Jones, S.L. Red Maple (Acer rubrum) Leaf Toxicosis in Horses: A Retrospective Study of 32 Cases. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2006, 20, 1197–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassan, A.; Ceriani, L.; Richardson, J.; Livaniou, A.; Ciacci, A.; Baldin, R.; Kovarich, S.; Fioravanzo, E.; Pavan, M.; Gibin, D.; et al. OpenFoodTox: EFSA’s Chemical Hazards Database 2018. Available online: https://zenodo.org/record/1252752#.W8Yc-2epWUn (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Katsuno, T.; Kasuga, H.; Kusano, Y.; Yaguchi, Y.; Tomomura, M.; Cui, J.; Yang, Z.; Baldermann, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Ohnishi, T.; et al. Characterisation of odorant compounds and their biochemical formation in green tea with a low temperature storage process. Food Chem. 2014, 148, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Kobayashi, E.; Katsuno, T.; Asanuma, T.; Fujimori, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Tomomura, M.; Mochizuki, K.; Watase, T.; Nakamura, Y.; et al. Characterisation of volatile and non-volatile metabolites in etiolated leaves of tea (Camellia sinensis) plants in the dark. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 2268–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Maple Leaf Concentrate Chemical Analysis. 2018. Available online: https://osf.io/h4zr3/ (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Pubchem 3-Methoxybenzaldehyde. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/11569 (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Pubchem Glutamic Acid. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/33032 (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Reeds, P.J.; Burrin, D.G.; Stoll, B.; Jahoor, F. Intestinal Glutamate Metabolism. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 978S–982S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pubchem Aspartic Acid. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5960 (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Pubchem Phenylalanine. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/6140 (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Pubchem Citric Acid. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/311 (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Pubchem Naringin. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/442428 (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Pubchem Coumarin. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/323 (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Ballin, N.Z.; Sørensen, A.T. Coumarin content in cinnamon containing food products on the Danish market. Food Control 2014, 38, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compound Discoverer 2.1 ChemSpider Search Node. Available online: https://mycompounddiscoverer.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/chemspider-datasources-cd2-1-update.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Beyer, J.; Peters, F.T.; Kraemer, T.; Maurer, H.H. Detection and validated quantification of toxic alkaloids in human blood plasma—Comparison of LC-APCI-MS with LC-ESI-MS/MS. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, A.L.; Foglia, P.; Gubbiotti, R.; Roccia, C.; Samperi, R.; Laganà, A. Development and validation of a liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure photoionization-tandem mass spectrometric method for the analysis of mycotoxins subjected to commission regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006 In cereals. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 6044–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosek, B.A.; Alter, G.; Banks, G.C.; Borsboom, D.; Bowman, S.D.; Breckler, S.J.; Buck, S.; Chambers, C.D.; Chin, G.; Christensen, G.; et al. Promoting an open research culture. Science 2015, 348, 1422–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willinsky, J. The unacknowledged convergence of open source, open access, and open science. First Monday 2005, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ross, J.S.; Krumholz, H.M. Ushering in a New Era of Open Science Through Data Sharing: The Wall Must Come Down. JAMA 2013, 309, 1355–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelfle, M.; Olliaro, P.; Todd, M.H. Open science is a research accelerator. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller, J.; Fitzgerald, B. Understanding Open Source Software Development; Addison-Wesley: London, UK, 2002; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani, K.R.; Wolf, R.G. Why hackers do what they do: Understanding motivation and effort in free/open source software projects. Perspect. Free Open Sour. Softw. Proj. 2005, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippel, E.V.; Krogh, G.V. Open source software and the “private-collective” innovation model: Issues for organization science. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Building Research Equipment with Free, Open-Source Hardware. Science 2012, 337, 1303–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J. Open-Source Lab: How to Build Your Own Hardware and Reduce Research Cost, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.M. Impacts of Open Source Hardware in Science and Engineering. Bridge 2017, 47, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Oberloier, S.; Pearce, J.M. General Design Procedure for Free and Open-Source Hardware for Scientific Equipment. Designs 2018, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, M.D.; Fobel, R.; Fobel, C.; Wheeler, A.R. Upon the Shoulders of Giants: Open-Source Hardware and Software in Analytical Chemistry. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 4330–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dybing, E.; Doe, J.; Groten, J.; Kleiner, J.; O’Brien, J.; Renwick, A.G.; Schlatter, J.; Steinberg, P.; Tritscher, A.; Walker, R.; et al. Hazard characterisation of chemicals in food and diet. Dose response, mechanisms and extrapolation issues. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002, 40, 237–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2006: Excluded and Invisible; UNICEF: Hong Kong, China, 2005; ISBN 978-92-806-3916-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fao.org SOFI 2018—The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. Available online: http://www.fao.org/state-of-food-security-nutrition/en/ (accessed on 5 December 2018).

| Name | Retention Time | Not in the Blank | Above Noise | Good Peak Shape | MS isotopic Pattern | MS Chem Spider Match | Leachable and Extractable Mass List Match | MS/MS mzCloud Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,3,6-Trimethylphenol | 16.70 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H − H2O] match | 50 | 5 | no match |

| 3-Methoxybenzaldehyde | 11.49 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 5 | 3 or 4 methoxybenzaldehyde, 82% |

| 4-Methoxybenzaldehyde | 12.99 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 5 | 3 or 4 methoxybenzaldehyde, 82% |

| 8-Hydroxyquinoline | 7.95 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 4 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Bensulfuron-methyl | 1.70 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| benzaldehyde | 23.12 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 9 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Cinnamaldehyde | 13.97 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | No match | no MS/MS |

| Coumarin | 17.63 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 32 | No match | 80% |

| Erythorbic acid | 2.10 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 27 | No match | no MS/MS |

| Diphenylamine | 42.50 | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 2 | no MS/MS |

| Ethyl benzoate | 19.65 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Ethyl cinnamate | 21.71 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | No match | Benzyl Methacrylate, 61% |

| Gallic acid | 13.15 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H − H2O] match | 16 | No match | no MS/MS |

| Indole | 7.95 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 42 | No match | no MS/MS |

| L-Glutamic acid | 1.74 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | No match | 99.40% |

| L-Histidine | 1.59 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 49 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| L-Isoleucine | 2.56 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 2 | no MS/MS |

| L-Methionine | 1.75 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 40 | 1 | no match |

| L-Phenylalanine | 4.02 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 1 | 99.60% |

| L-Proline | 1.80 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | No match | no MS/MS |

| L-Tyrosine | 13.37 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Naringin dihydrochalcone | 22.78 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + Na] match | 0 | No match | no match |

| Nicotinamide | 2.12 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 49 | No match | no MS/MS |

| Propyl gallate | 8.56 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 49 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| salicylic acid | 15.77 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 39 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Tentoxin | 19.06 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | 6 | No match | no match |

| Terephthalic acid | 9.71 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 40 | 3 | no MS/MS |

| Triphenylphosphine oxide | 34.86 | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 10 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Thidiazuron | 1.92 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 31 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Trichlorfon | 1.51 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 2 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Vanillin | 16.17 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M + H] match | 50 | 2 | no MS/MS |

| Name | Retention Time | Not in Blank | Above Noise | Good Peak Shape | MS isotopic Pattern | MS Chem Spider Match | Leachable and Extractable Mass List Match | MS/MS mzCloud Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citric acid | 2.46 | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | [M − H] match | 12 | 2 | 89.4%% |

| Gallic acid | 3.72 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M − H] match | 16 | no match | no match |

| L-Aspartic acid | 1.73 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M − H] match | 21 | no match | 96.8 |

| L-Glutamic acid | 1.73 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M − H] match | 50 | no match | 99.50% |

| Naringin | 22.93 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M − H] match | 12 | no match | 80.30% |

| Salicylic acid | 21.71 | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | [M − H] match | 40 | 1 | no MS/MS |

| Succinic acid | 2.77 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | [M − H] match | 16 | 1 | no MS/MS |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pearce, J.M.; Khaksari, M.; Denkenberger, D. Preliminary Automated Determination of Edibility of Alternative Foods: Non-Targeted Screening for Toxins in Red Maple Leaf Concentrate. Plants 2019, 8, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8050110

Pearce JM, Khaksari M, Denkenberger D. Preliminary Automated Determination of Edibility of Alternative Foods: Non-Targeted Screening for Toxins in Red Maple Leaf Concentrate. Plants. 2019; 8(5):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8050110

Chicago/Turabian StylePearce, Joshua M., Maryam Khaksari, and David Denkenberger. 2019. "Preliminary Automated Determination of Edibility of Alternative Foods: Non-Targeted Screening for Toxins in Red Maple Leaf Concentrate" Plants 8, no. 5: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8050110

APA StylePearce, J. M., Khaksari, M., & Denkenberger, D. (2019). Preliminary Automated Determination of Edibility of Alternative Foods: Non-Targeted Screening for Toxins in Red Maple Leaf Concentrate. Plants, 8(5), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8050110