Taxonomy—Dependent Seed Tocochromanol Composition in the Rutaceae Family: Application of Sustainable Approach for Their Extraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

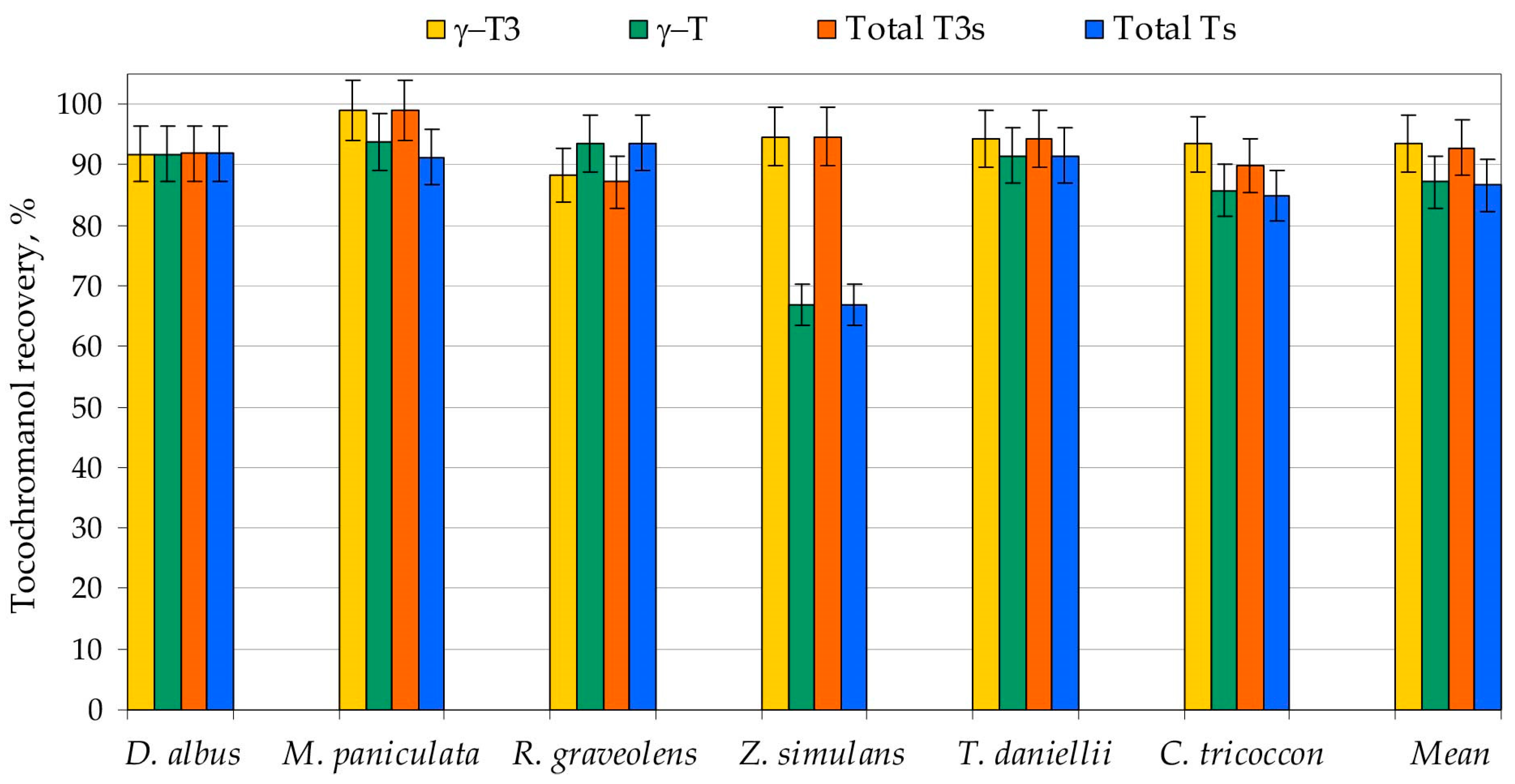

2.1. Saponification and UAEE Recovery and Measurement Repeatability

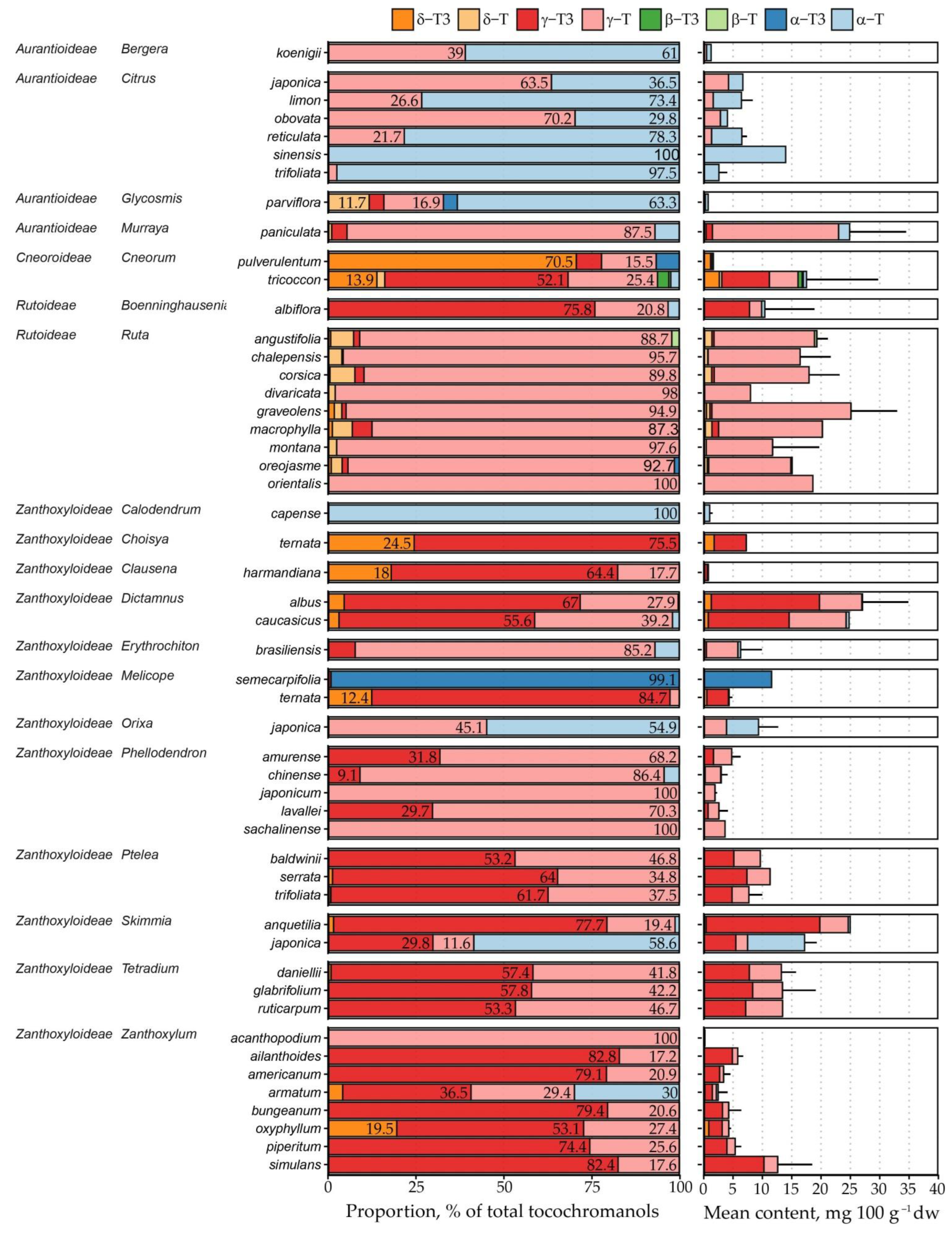

2.2. Free Tocochromanol Profile

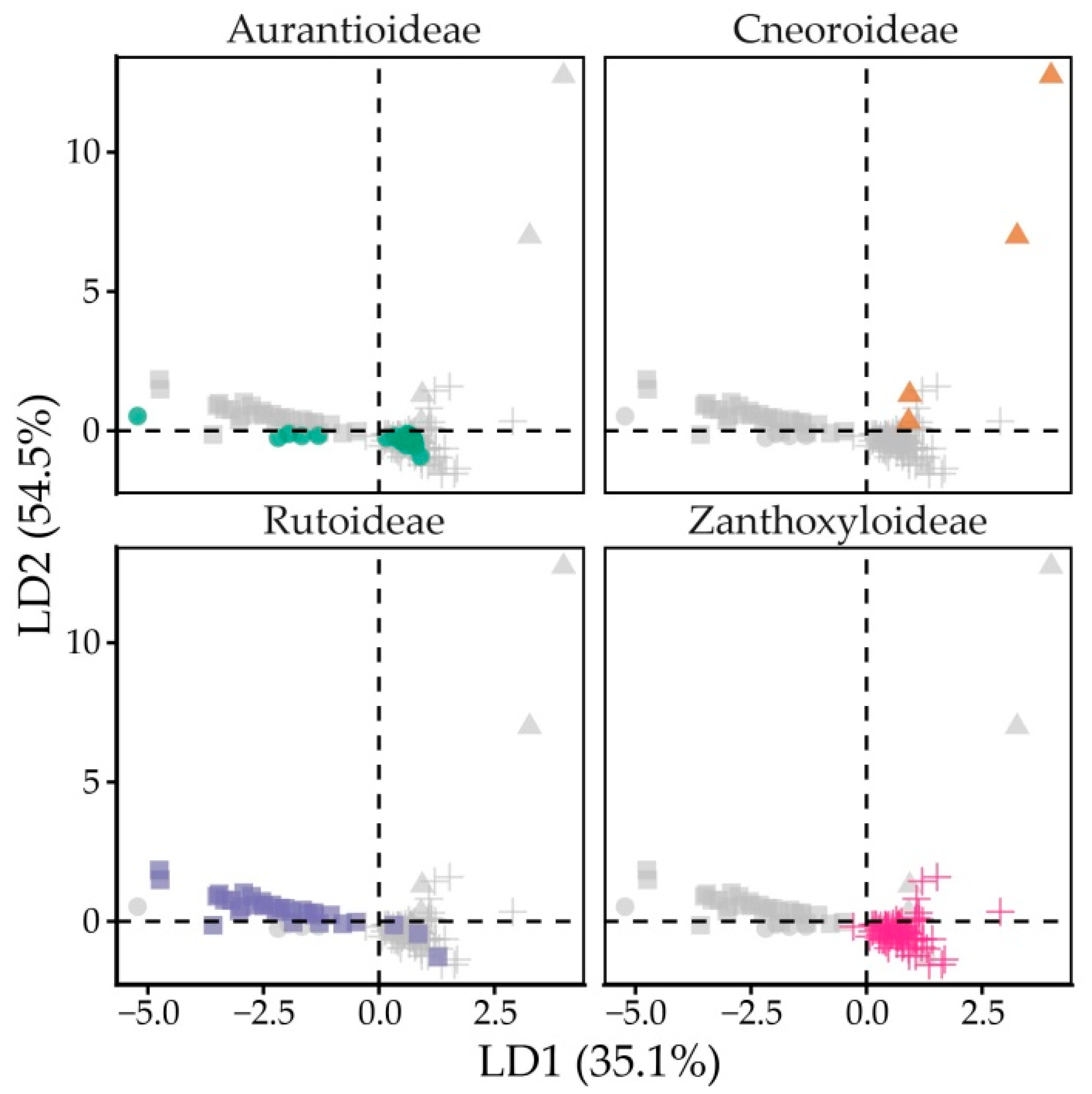

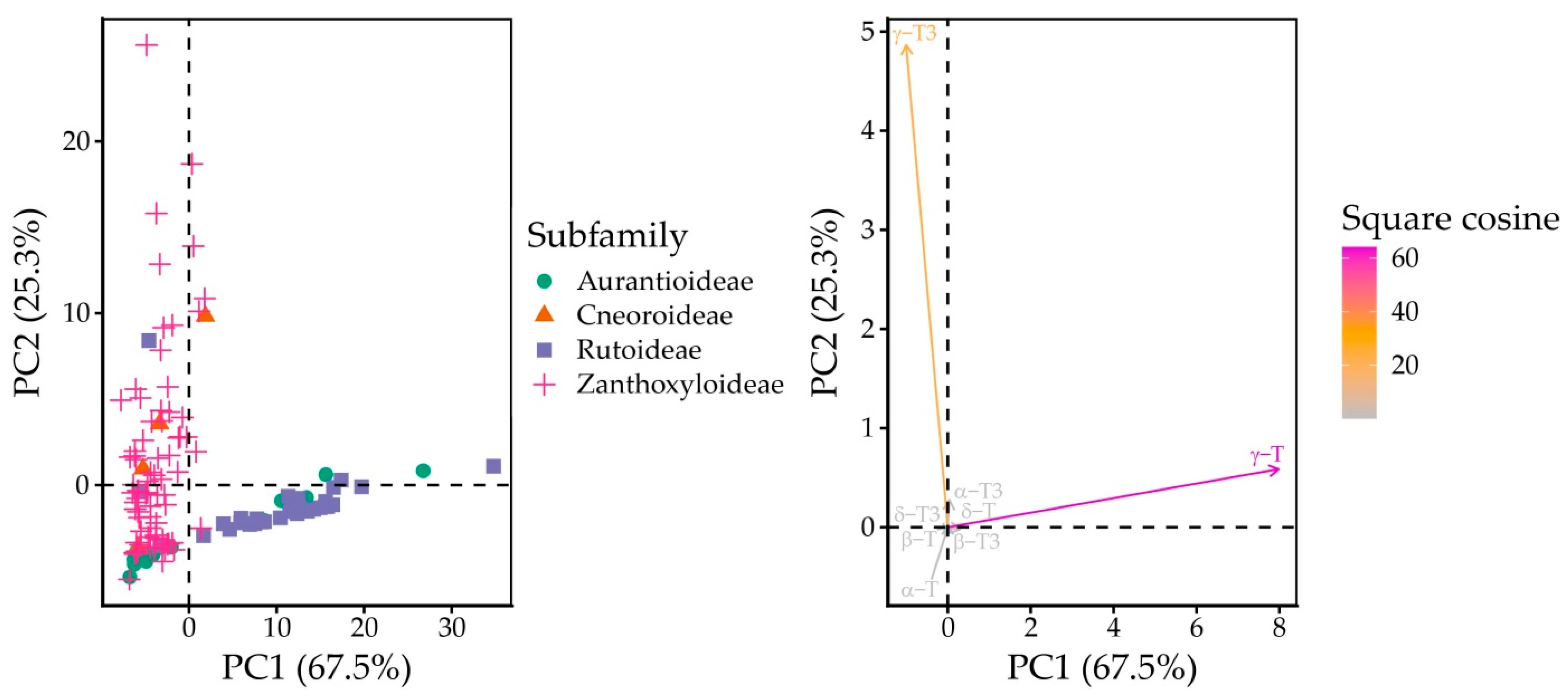

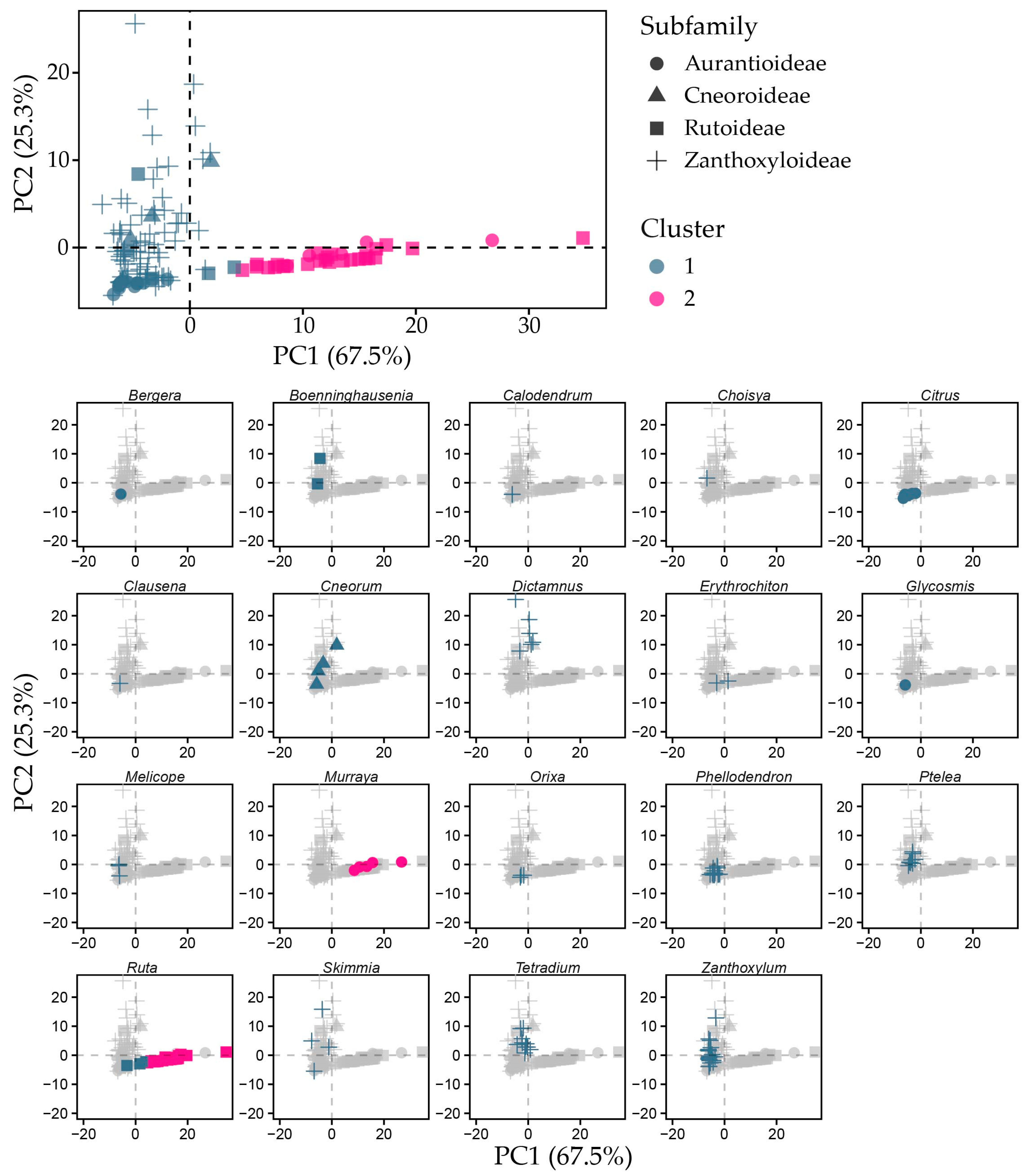

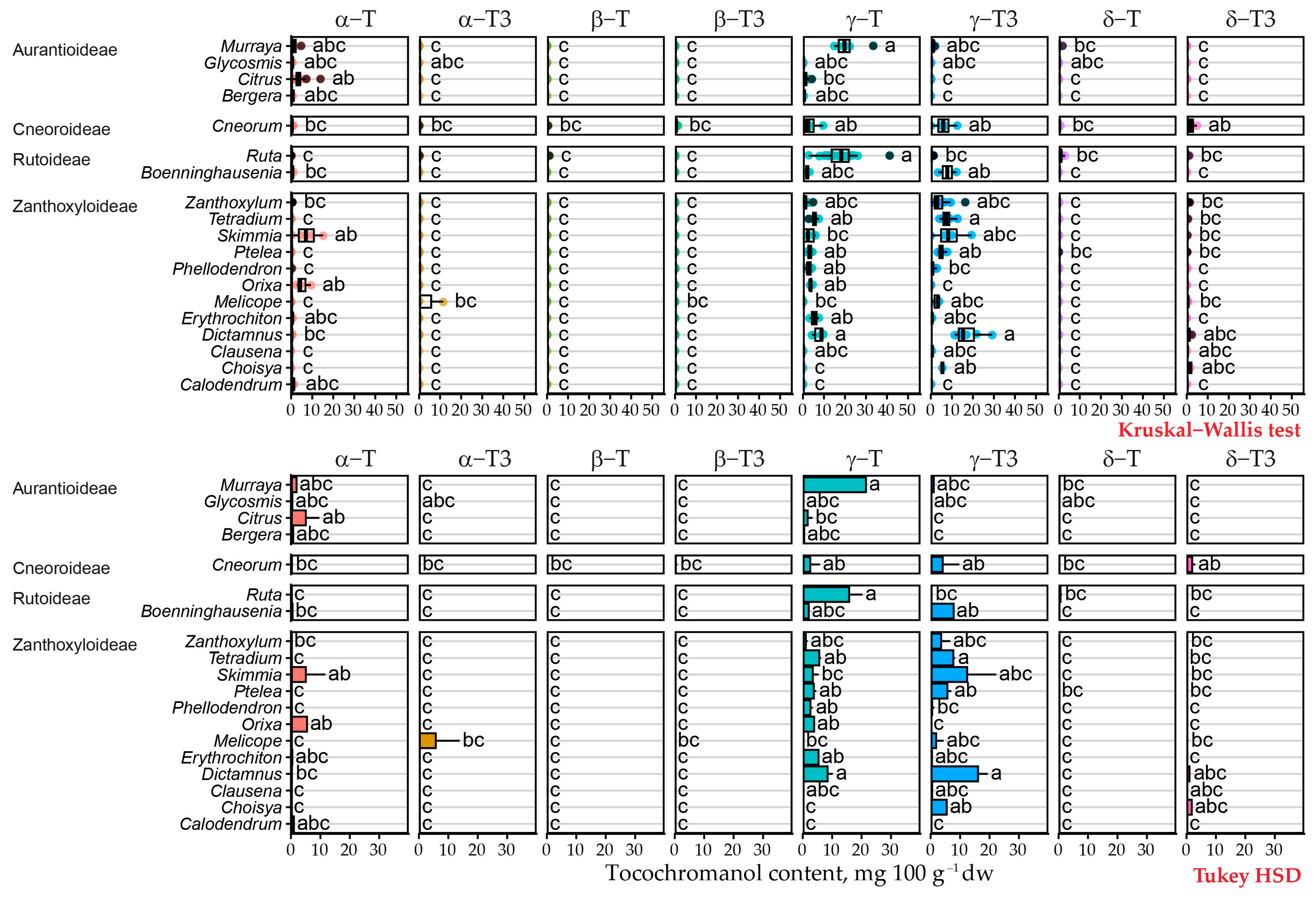

2.3. Free Tocochromanol Composition as Shaped by Phylogeny

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Tocochromanols Extraction

3.3.1. Saponification

3.3.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction in Ethanol (UAEE)

3.3.3. Method Validation

3.4. Tocochromanol Determination by Reversed-Phase Liquid-Chromatography with Fluorescent Detection (RPLC-FLD)

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

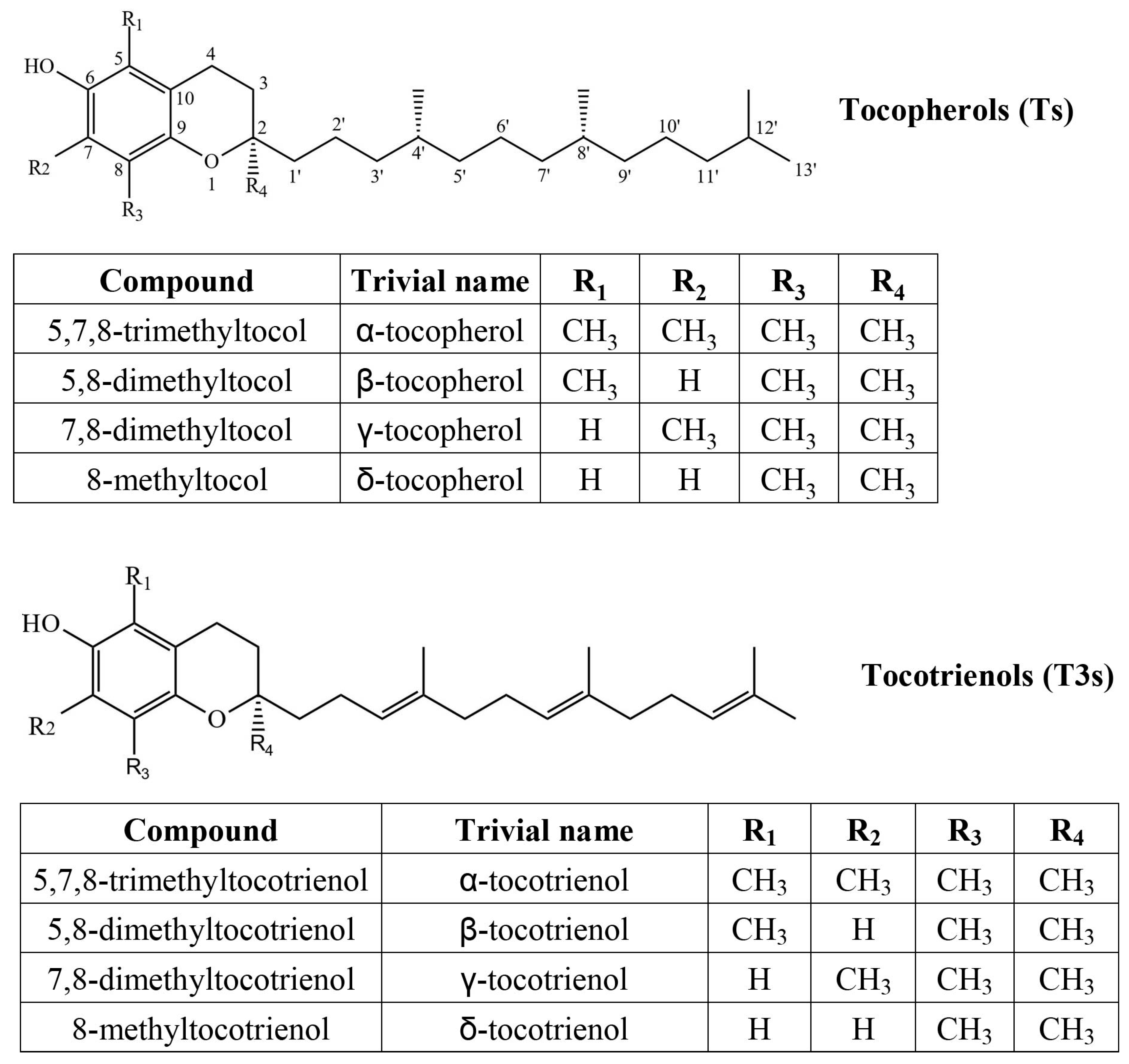

Abbreviations

References

- Appelhans, M.S.; Bayly, M.J.; Heslewood, M.M.; Groppo, M.; Verboom, G.A.; Forster, P.I.; Kallunki, J.A.; Duretto, M.F. A new subfamily classification of the Citrus family (Rutaceae) based on six nuclear and plastid markers. Taxon 2021, 70, 1035–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppo, M.; Afonso, L.F.; Pirani, J.R. A review of systematics studies in the Citrus family (Rutaceae, Sapindales), with emphasis on American groups. Rev. Bras. Bot. 2022, 45, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, X.; Battino, M.; Wei, X.; Shi, J.; Zhao, L.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Shi, B.; Zou, X. A comparative overview on chili pepper (capsicum genus) and sichuan pepper (zanthoxylum genus): From pungent spices to pharma-foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhaus, M. Characterization of the major odor-active compounds in the leaves of the curry tree Bergera koenigii L. by aroma extract dilution analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 4060–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Minero, F.J.; Bravo-Díaz, L.; Moreno-Toral, E. Pharmacy and fragrances: Traditional and current use of plants and their extracts. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mène-Saffrané, L. Vitamin E biosynthesis and its regulation in plants. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, F.; Zacarias, L.; Rodrigo, M.J. Regulation of tocopherol biosynthesis during fruit maturation of different Citrus species. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 743993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cahoon, R.E.; Hunter, S.C.; Chen, M.; Han, J.; Cahoon, E.B. Genetic and biochemical basis for alternative routes of tocotrienol biosynthesis for enhanced vitamin E antioxidant production. Plant J. 2013, 73, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicka, B.; Trela-Makowej, A.; Latowski, D.; Strzalka, K.; Szymańska, R. Antioxidant and signaling role of plastid-derived isoprenoid quinones and chromanols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mène-Saffrané, L.; DellaPenna, D. Biosynthesis, regulation and functions of tocochromanols in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Yang, R.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Yu, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, P. Comparative advantages of chemical compositions of specific edible vegetable oils. Oil Crop Sci. 2023, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.; Güneşer, B.A. Cold pressed versus solvent extracted lemon (Citrus limon L.) seed oils: Yield and properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1891–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assefa, A.D.; Saini, R.K.; Keum, Y.-S. Fatty acids, tocopherols, phenolic and antioxidant properties of six citrus fruit species: A comparative study. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 1665–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Naseer, R.; Bhanger, M.; Ashraf, S.; Talpur, F.N.; Aladedunye, F.A. Physico-chemical characteristics of citrus seeds and seed oils from Pakistan. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2008, 85, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndayishimiye, J.; Lim, D.J.; Chun, B.S. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of oils obtained from a mixture of citrus by-products using a modified supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 57, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, S.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Gu, Q.; Guo, X.; Hu, Y. Tocochromanols and chlorophylls accumulation in young pomelo (Citrus maxima) during early fruit development. Foods 2021, 10, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siger, A.; Górnaś, P. Free tocopherols and tocotrienols in 82 plant species’ oil: Chemotaxonomic relation as demonstrated by PCA and HCA. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Denaro, M.; Di Gristina, E.; Mastracci, L.; Grillo, F.; Cornara, L.; Trombetta, D. Pharmacognostic approach to evaluate the micromorphological, phytochemical and biological features of Citrus lumia seeds. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Juhaimi, F.; Özcan, M.M.; Uslu, N.; Ghafoor, K. The effect of drying temperatures on antioxidant activity, phenolic compounds, fatty acid composition and tocopherol contents in citrus seed and oils. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacrida, C.R.; Kimura, M.; Jorge, N. Phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of citrus seed oils. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2012, 18, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.; Jorge, N. Bioactive properties and antioxidant capacity of oils extracted from citrus fruit seeds. Acta Aliment. 2019, 48, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaus, B.; Özcan, M.M. Chemical evaluation of citrus seeds, an agro-industrial waste, as a new potential source of vegetable oils. Grasas Aceites 2012, 63, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhaimi, F.A.L.; Matthäus, B.; Özcan, M.M.; Ghafoor, K. The physico-chemical properties of some citrus seeds and seed oils. Z. Für Naturforschung C 2016, 71, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petkova, Z.; Antova, G.; Kulina, H.; Teneva, O.; Angelova-Romova, M. Preliminary characterization of glyceride oil content and tocopherol composition in seeds from selected wild plant species of the Bulgarian flora. Molecules 2025, 30, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, G.; Wessjohann, L.; Bigirimana, J.; Monica, H.; Jansen, M.; Guisez, Y.; Caubergs, R.; Horemans, N. Accumulation of tocopherols and tocotrienols during seed development of grape (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Albert Lavallée). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2006, 44, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazdiņa, D.; Mišina, I.; Dukurs, K.; Górnaś, P. Seed tocochromanol-based chemotaxonomy of Euroasian grapevine (Vitaceae) species. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2026, 150, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, S.L.; Robson, N.K.B. Taxonomy and chemotaxonomy of the genus Hypericum. Med. Aromat. Plant Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Górnaś, P.; Siger, A.; Czubinski, J.; Dwiecki, K.; Segliņa, D.; Nogala-Kalucka, M. An alternative RP-HPLC method for the separation and determination of tocopherol and tocotrienol homologues as butter authenticity markers: A comparative study between two European countries. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2014, 116, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Baškirovs, G.; Siger, A. Free and esterified tocopherols, tocotrienols and other extractable and non-extractable tocochromanol-related molecules: Compendium of knowledge, future perspectives and recommendations for chromatographic techniques, tools, and approaches used for tocochromanol determination. Molecules 2022, 27, 6560. [Google Scholar]

- Górnaś, P.; Lazdiņa, D.; Mišina, I.; Sipeniece, E.; Segliņa, D. Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton) seeds: An exceptional source of tocotrienols. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 331, 113107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Mišina, I.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Perkons, I.; Pugajeva, I.; Segliņa, D. Simultaneous extraction of tocochromanols and flavan-3-ols from the grape seeds: Analytical and industrial aspects. Food Chem. 2025, 462, 140913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauß, S.; Darwisch, V.; Vetter, W. Occurrence of tocopheryl fatty acid esters in vegetables and their non-digestibility by artificial digestion juices. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišina, I.; Sipeniece, E.; Rudzińska, M.; Grygier, A.; Radzimirska-Graczyk, M.; Kaufmane, E.; Segliņa, D.; Lācis, G.; Górnaś, P. Associations between oil yield and profile of fatty acids, sterols, squalene, carotenoids, and tocopherols in seed oil of selected Japanese quince genotypes during fruit development. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2020, 122, 1900386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britz, S.J.; Kremer, D.F. Warm temperatures or drought during seed maturation increase free α-tocopherol in seeds of soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6058–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, F.D.; Möllers, C. Changes in tocopherol and plastochromanol-8 contents in seeds and oil of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) during storage as influenced by temperature and air oxygen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, V.; Vanier, N.L.; Ferreira, C.D.; Paraginski, R.T.; Monks, J.L.F.; Elias, M.C. Changes in the bioactive compounds content of soybean as a function of grain moisture content and temperature during long-term storage. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, H762–H768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghada, B.; Amel, O.; Aymen, M.; Aymen, A.; Amel, S.H. Phylogenetic patterns and molecular evolution among ‘True citrus fruit trees’ group (Rutaceae family and Aurantioideae subfamily). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 253, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Song, W.; Liu, J.; Shi, C.; Wang, S. Comparative chloroplast genome analysis of Citrus (Rutaceae) species: Insights into genomic characterization, phylogenetic relationships, and discrimination of subgenera. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 313, 111909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Luo, H.; Xie, Z.; Yu, H.; Chang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zheng, X.; Sheng, J. Comparative chloroplast genomics of Rutaceae: Structural divergence, adaptive evolution, and phylogenomic implications. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1675536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, L.P.; Tomasello, S.; Wen, J.; Appelhans, M.S. Phylogeny of the species-rich pantropical genus Zanthoxylum (Rutaceae) based on hybrid capture. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2025, 211, 108398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Marín, B.; Míguez, F.; Méndez-Fernández, L.; Agut, A.; Becerril, J.M.; García-Plazaola, J.I.; Kranner, I.; Colville, L. Seed carotenoid and tocochromanol composition of wild Fabaceae species is shaped by phylogeny and ecological factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siles, L.; Cela, J.; Munné-Bosch, S. Vitamin E analyses in seeds reveal a dominant presence of tocotrienols over tocopherols in the Arecaceae family. Phytochemistry 2013, 95, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P. Domination of tocotrienols over tocopherols in seed oils of sixteen species belonging to the Apiaceae family. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, E. Fatty acids and tocochromanol patterns of some Turkish Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) plants: A chemotaxonomic approach. Acta Bot. Gall. 2007, 154, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.A.; Aitzetmüller, K. Untersuchungen über die tocopherol-und tocotrienolzusammensetzung der samenöle einiger vertreter der familie Apiaceae. Lipid/Fett 1995, 97, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo, F.; Vaissayre, V.; Serret, J.; Avallone, S.; Domonhédo, H.; Jacob, F.; Dussert, S. Natural diversity in the carotene, tocochromanol and fatty acid composition of crude palm oil. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genus | Species | δ-T3 | γ-T3 | δ-T | γ-T | α-T | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aurantioideae subfamily | |||||||

| Bergera | koenigii (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | 0.50 | 0.80 | 1.26 |

| Citrus | japonica (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | 4.20 | 2.40 | 6.67 |

| limon (n = 3) | ND | ND | ND | 1.6 ± 0.10 | 4.80 ± 2.00 | 6.42 ± 1.91 | |

| obovata (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | 2.80 | 1.20 | 4.04 | |

| reticulata (n = 3) | ND | ND | ND | 1.33 ± 1.03 | 5.13 ± 1.79 | 6.50 ± 0.84 | |

| sinensis (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 14.00 | 13.96 | |

| trifoliata (n = 5) | ND | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 2.58 ± 1.41 | 2.59 ± 1.4 | |

| Murraya | paniculata (n = 5) | ND | 1.10 ± 0.66 | 0.40 ± 0.79 | 21.48 ± 7.27 | 1.88 ± 1.76 | 24.87 ± 9.64 |

| Glycosmis | parviflora (n = 2) | ND | ND | 0.10 ± 0 | 0.10 ± 0 | 0.50 ± 0.14 | 0.76 ± 0.11 |

| Cneoroideae subfamily | |||||||

| Cneorum | pulverulentum (n = 1) | 1.20 | 0.10 | ND | 0.30 | ND | 1.64 |

| tricoccon (n = 3) | 2.63 ± 2.16 | 8.10 ± 4.06 | 0.43 ± 0.42 | 4.87 ± 4.24 | 0.60 ± 0.56 | 17.52 ± 12.21 | |

| Rutoideae subfamily | |||||||

| Boenninghausenia | albiflora (n = 2) | ND | 7.80 ± 6.22 | ND | 2.05 ± 1.48 | 0.55 ± 0.78 | 10.42 ± 8.47 |

| Ruta | angustifolia (n = 3) | 0.13 ± 0.15 | 0.37 ± 0.47 | 1.23 ± 0.25 | 17.13 ± 2.11 | 0.03 ± 0.06 | 19.29 ± 1.87 |

| chalepensis (n = 5) | ND | 0.04 ± 0.09 | 0.70 ± 0.45 | 15.70 ± 4.97 | ND | 16.43 ± 5.23 | |

| corsica (n = 5) | 0.10 ± 0.12 | 0.42 ± 0.13 | 1.24 ± 0.34 | 16.18 ± 4.87 | ND | 17.95 ± 5.17 | |

| divaricata (n = 1) | ND | ND | 0.20 | 7.80 | ND | 7.97 | |

| graveolens (n = 9) | 0.46 ± 0.26 | 0.33 ± 0.52 | 0.58 ± 1.03 | 23.70 ± 7.50 | ND | 25.08 ± 7.86 | |

| macrophylla (n = 1) | 0.30 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 17.70 | 0.10 | 20.25 | |

| montana (n = 3) | ND | ND | 0.43 ± 0.75 | 11.3 ± 7.44 | ND | 11.73 ± 7.95 | |

| oreojasme (n = 1) | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 14.00 | ND | 15.07 | |

| orientalis (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | 18.60 | ND | 18.60 | |

| Zanthoxyloideae subfamily | |||||||

| Calodendrum | capense (n = 2) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.00 ± 0.57 | 1.01 ± 0.51 |

| Clausena | harmandiana (n = 1) | 0.10 | 0.50 | ND | 0.10 | ND | 0.77 |

| Dictamnus | albus (n = 5) | 1.26 ± 0.69 | 18.44 ± 7.22 | ND | 7.24 ± 2.42 | 0.12 ± 0.18 | 27.07 ± 7.8 |

| caucasicus (n = 1) | 0.80 | 13.80 | ND | 9.70 | 0.50 | 24.78 | |

| Melicope | semecarpifolia (n = 1) | ND | 0.10 | ND | ND | ND | 11.57 |

| ternata (n = 2) | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 3.65 ± 0.35 | ND | 0.15 ± 0.07 | ND | 4.33 ± 0.54 | |

| Orixa | japonica (n = 3) | ND | ND | ND | 3.87 ± 0.64 | 5.47 ± 3.48 | 9.34 ± 3.35 |

| Phellodendron | amurense (n = 5) | ND | 1.66 ± 1.24 | ND | 3.12 ± 0.85 | ND | 4.77 ± 1.48 |

| chinense (n = 3) | ND | 0.23 ± 0.40 | ND | 2.63 ± 1.40 | 0.10 ± 0.17 | 3.00 ± 1.08 | |

| japonicum (n = 2) | ND | ND | ND | 1.95 ± 0.35 | ND | 1.91 ± 0.36 | |

| lavallei (n = 3) | ND | 0.73 ± 0.59 | ND | 1.83 ± 1.07 | ND | 2.57 ± 1.54 | |

| sachalinense (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | 3.60 | ND | 3.64 | |

| Skimmia | anquetilia (n = 1) | 0.40 | 19.40 | ND | 4.80 | 0.30 | 24.96 |

| japonica (n = 3) | ND | 5.47 ± 5.03 | ND | 2.00 ± 3.46 | 9.73 ± 5.26 | 17.20 ± 2.04 | |

| Tetradium | daniellii (n = 7) | 0.09 ± 0.23 | 7.70 ± 2.58 | ND | 5.46 ± 1.56 | ND | 13.23 ± 2.50 |

| glabrifolium (n = 2) | ND | 8.35 ± 6.01 | ND | 5.05 ± 0.35 | ND | 13.41 ± 5.69 | |

| ruticarpum (n = 1) | ND | 7.20 | ND | 6.30 | ND | 13.43 | |

| Zanthoxylum | acanthopodium (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | 0.20 | ND | 0.20 |

| ailanthoides (n = 3) | ND | 4.90 ± 1.48 | ND | 0.90 ± 0.52 | ND | 5.80 ± 0.90 | |

| americanum (n = 2) | ND | 2.70 ± 1.13 | ND | 0.65 ± 0.07 | ND | 3.39 ± 1.18 | |

| armatum (n = 6) | 0.18 ± 0.40 | 1.28 ± 1.21 | ND | 0.68 ± 0.61 | 0.33 ± 0.28 | 2.46 ± 1.61 | |

| bungeanum (n = 2) | ND | 3.20 ± 0.99 | ND | 1.05 ± 1.06 | ND | 4.25 ± 2.14 | |

| oxyphyllum (n = 2) | 0.90 ± 0.85 | 2.30 ± 0.71 | ND | 1.10 ± 1.13 | ND | 4.26 ± 0.38 | |

| piperitum (n = 3) | ND | 3.93 ± 1.21 | ND | 1.40 ± 1.21 | ND | 5.36 ± 1.01 | |

| simulans (n = 4) | ND | 10.28 ± 4.29 | ND | 2.33 ± 1.66 | ND | 12.59 ± 5.87 | |

| Choisya | ternata (n = 1) | 1.80 | 5.50 | ND | ND | ND | 7.24 |

| Erythrochiton | brasiliensis (n = 2) | ND | 0.45 ± 0.07 | ND | 5.35 ± 3.18 | 0.45 ± 0.35 | 6.29 ± 3.62 |

| Ptelea | baldwinii (n = 1) | ND | 5.10 | ND | 4.50 | ND | 9.64 |

| serrata (n = 1) | 0.10 | 7.20 | ND | 3.90 | ND | 11.29 | |

| trifoliata (n = 6) | 0.05 ± 0.12 | 4.78 ± 1.59 | ND | 2.88 ± 0.77 | ND | 7.70 ± 2.25 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lazdiņa, D.; Mišina, I.; Dukurs, K.; Górnaś, P. Taxonomy—Dependent Seed Tocochromanol Composition in the Rutaceae Family: Application of Sustainable Approach for Their Extraction. Plants 2026, 15, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030455

Lazdiņa D, Mišina I, Dukurs K, Górnaś P. Taxonomy—Dependent Seed Tocochromanol Composition in the Rutaceae Family: Application of Sustainable Approach for Their Extraction. Plants. 2026; 15(3):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030455

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazdiņa, Danija, Inga Mišina, Krists Dukurs, and Paweł Górnaś. 2026. "Taxonomy—Dependent Seed Tocochromanol Composition in the Rutaceae Family: Application of Sustainable Approach for Their Extraction" Plants 15, no. 3: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030455

APA StyleLazdiņa, D., Mišina, I., Dukurs, K., & Górnaś, P. (2026). Taxonomy—Dependent Seed Tocochromanol Composition in the Rutaceae Family: Application of Sustainable Approach for Their Extraction. Plants, 15(3), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030455