Identification and Development of Pathogen- and Pest-Specific Defense–Resistance-Associated SSR Marker Candidates Assisted by Machine Learning and Discovery of Putative QTL Hotspots in Camellia sinensis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Targeted Defense-Resistance-Associated Genes and Loci

2.2. Genomes and Assemblies

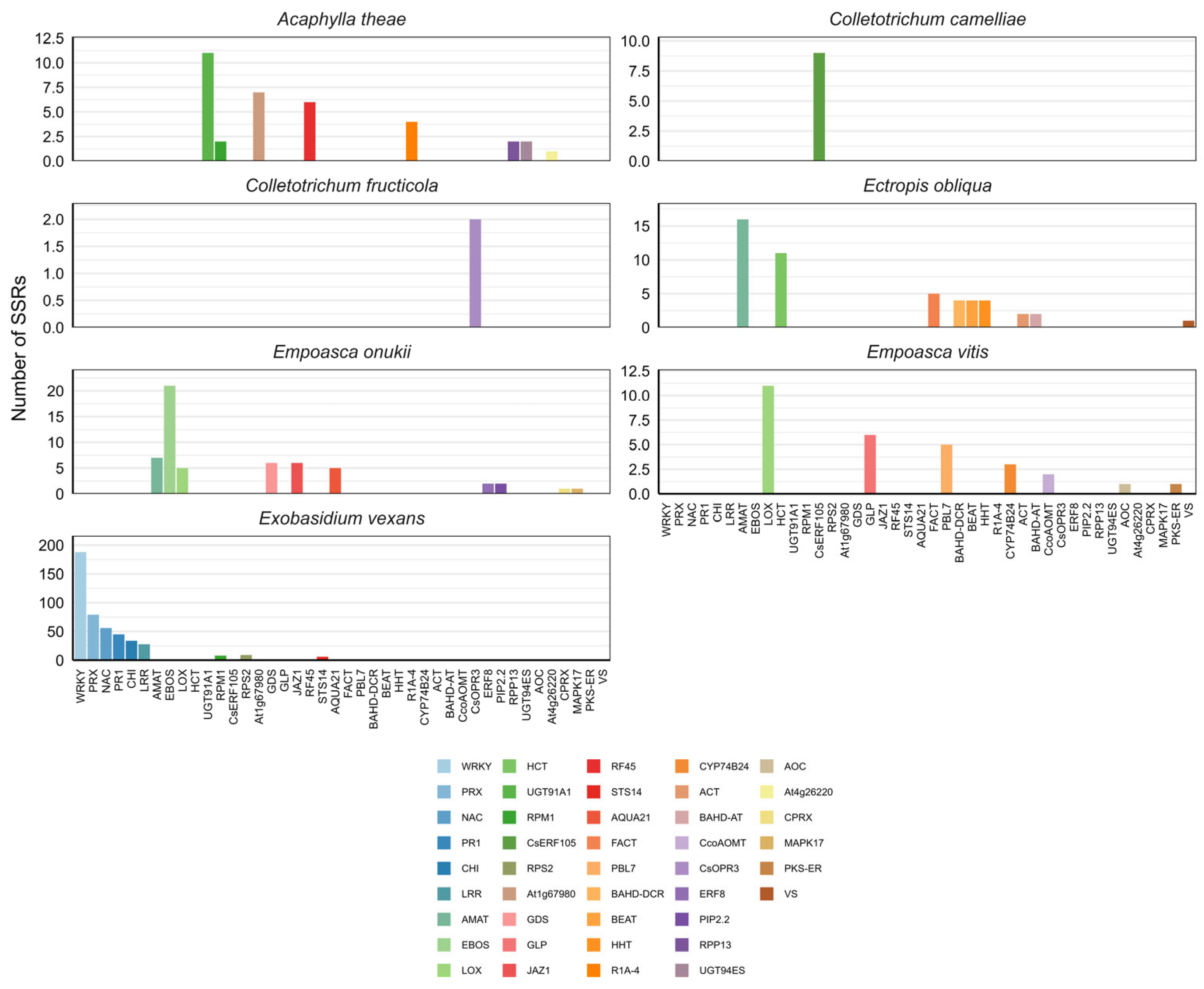

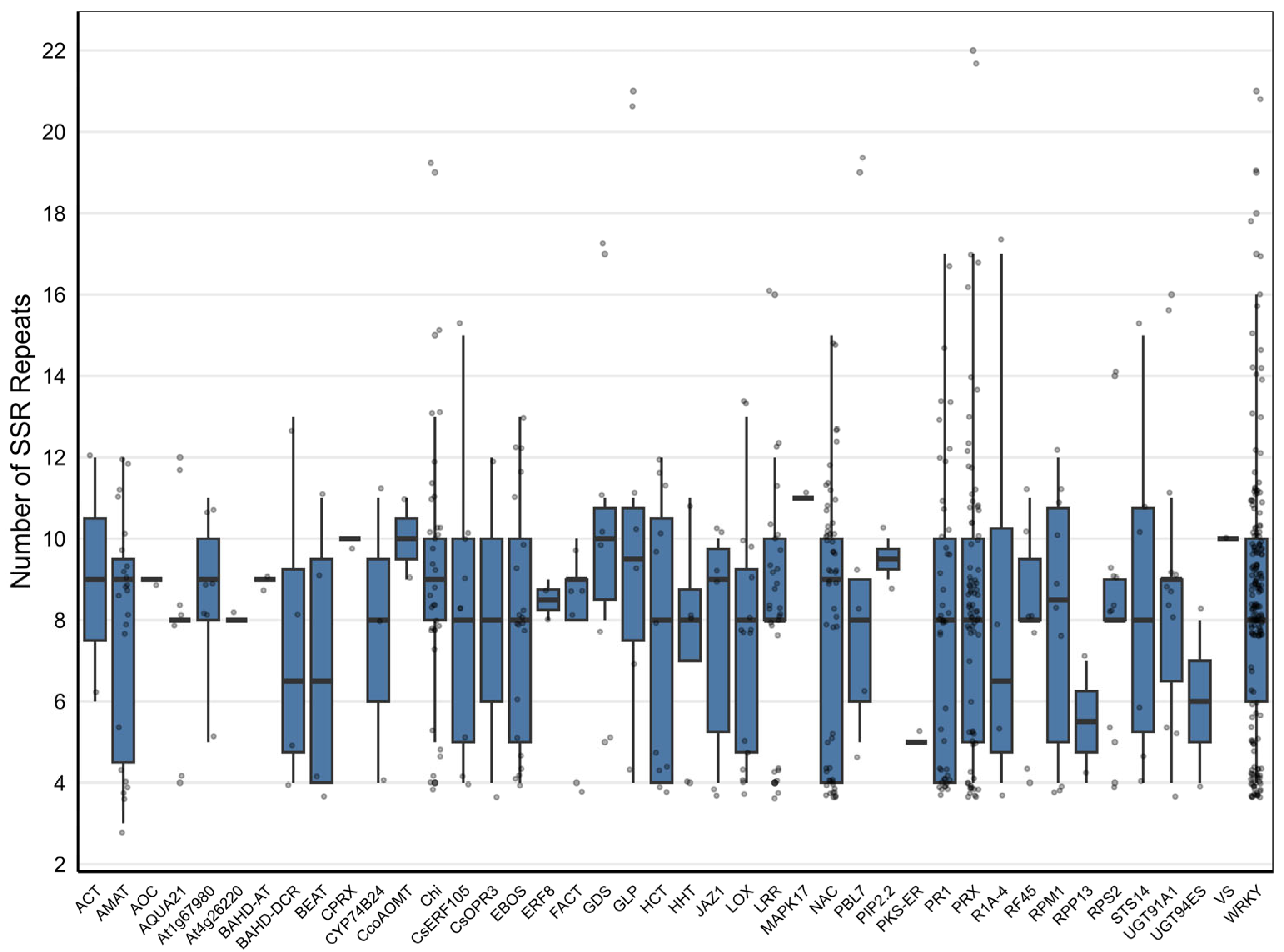

2.3. SSR-Identified Loci

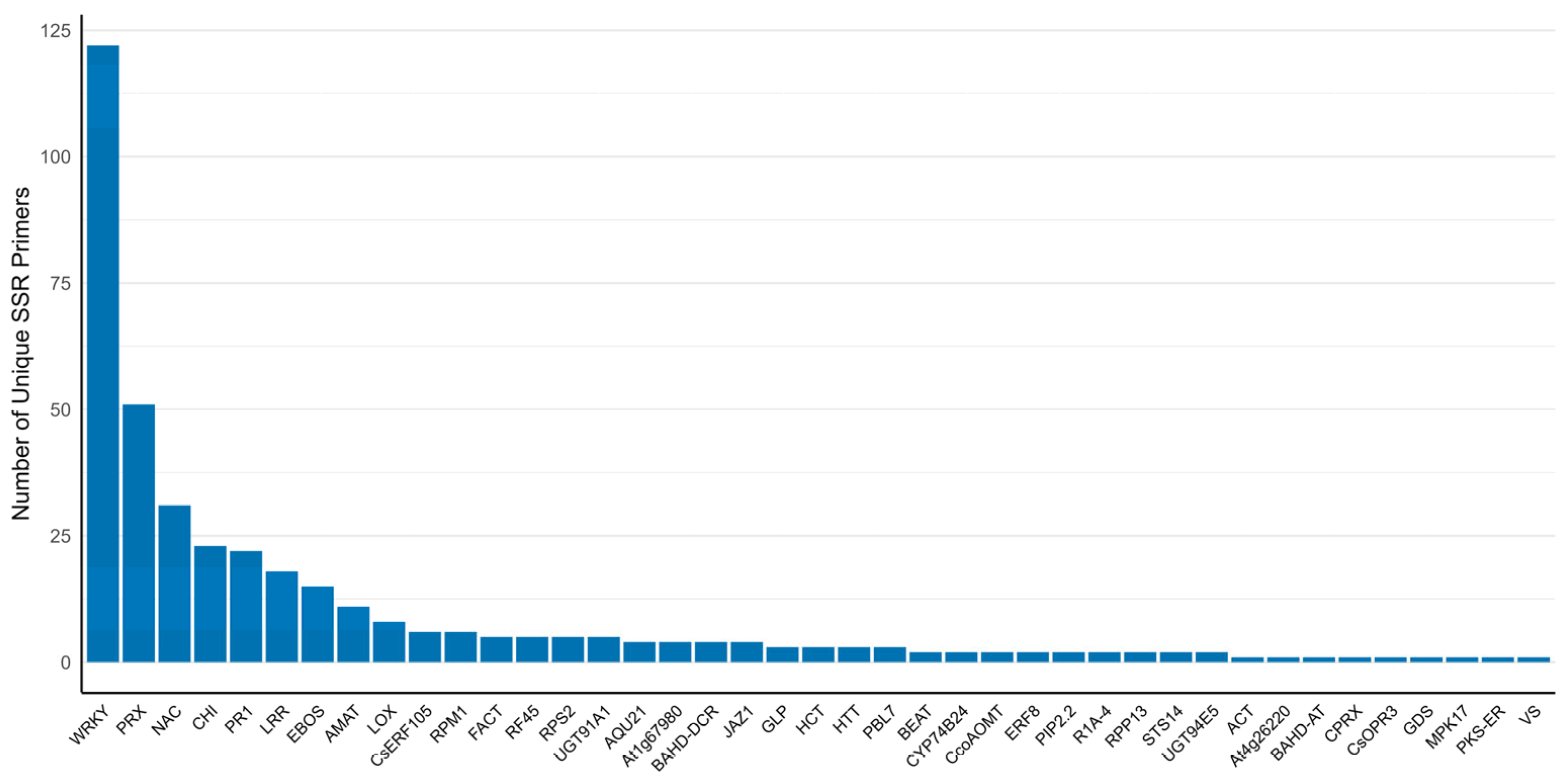

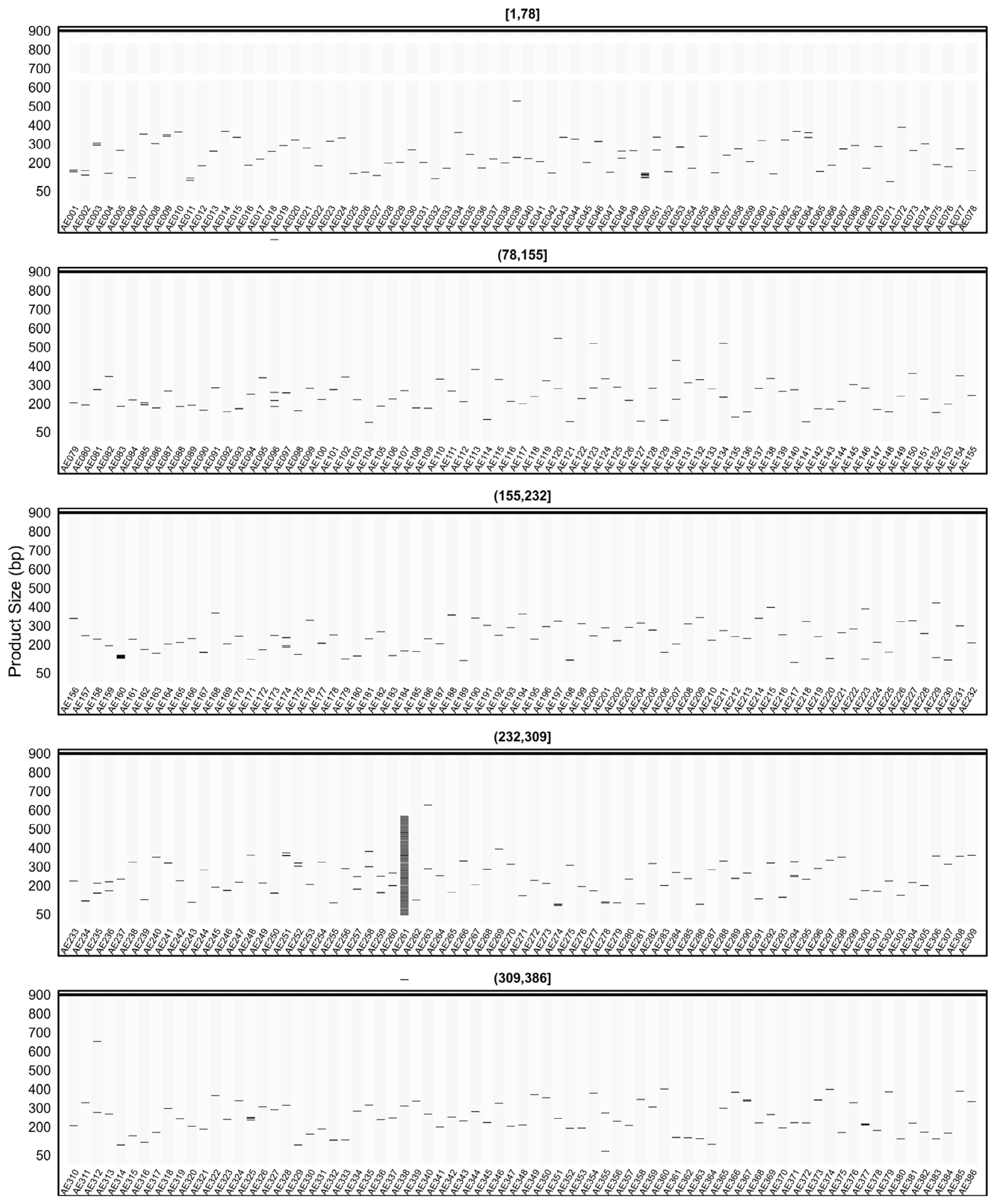

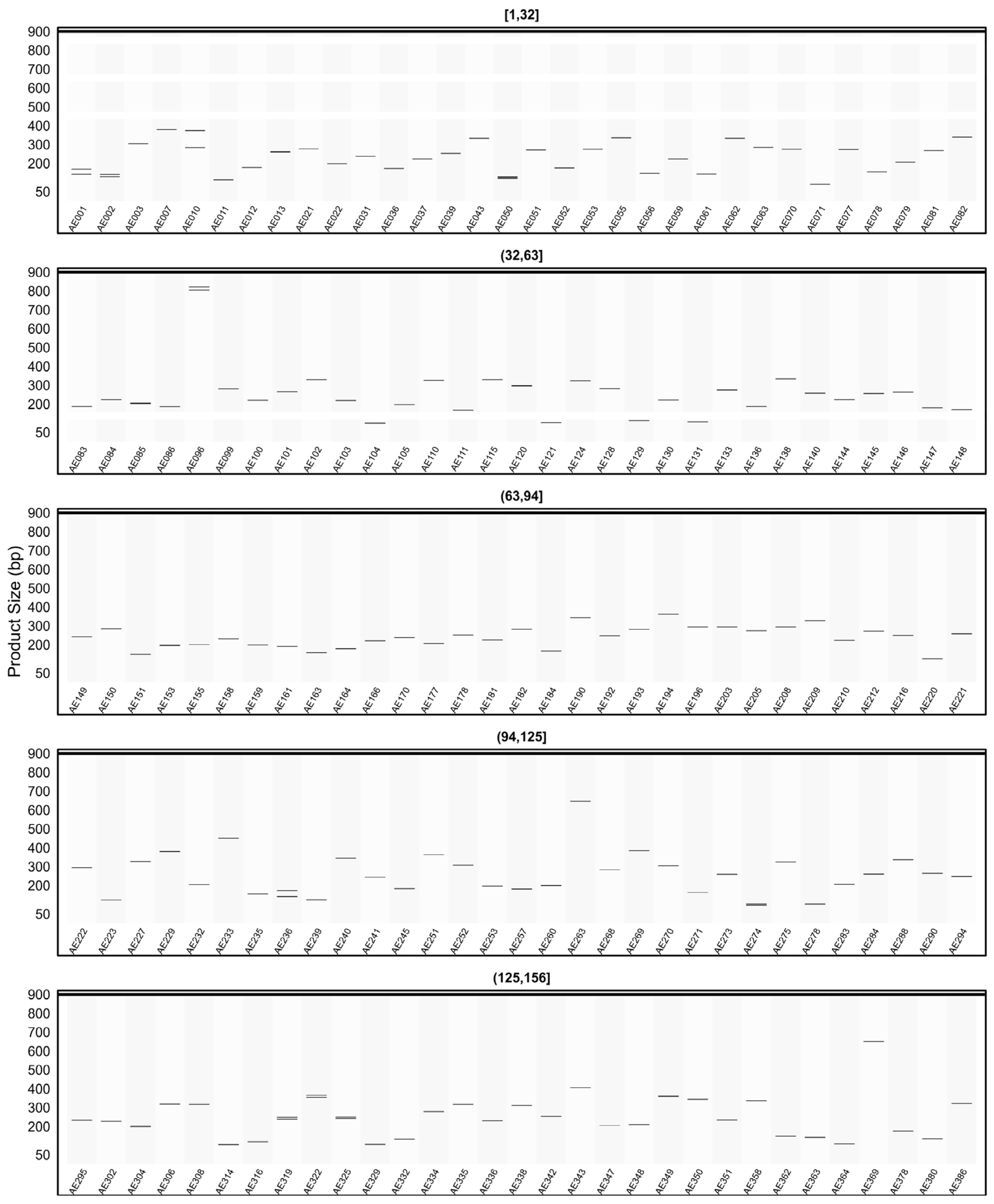

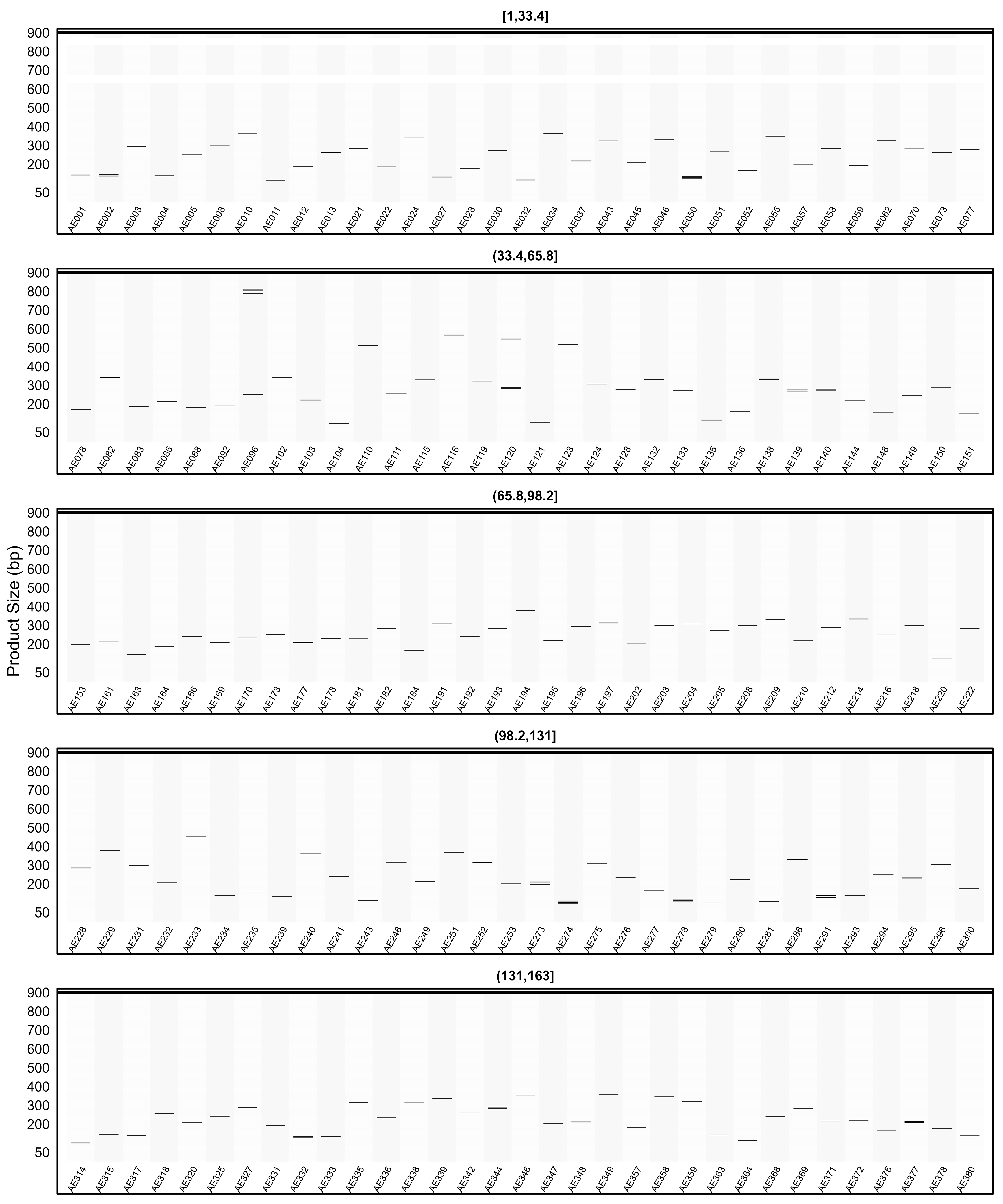

2.4. Final SSR Panel and pQTL Hotspots

2.5. Random Forest Ablation Analysis

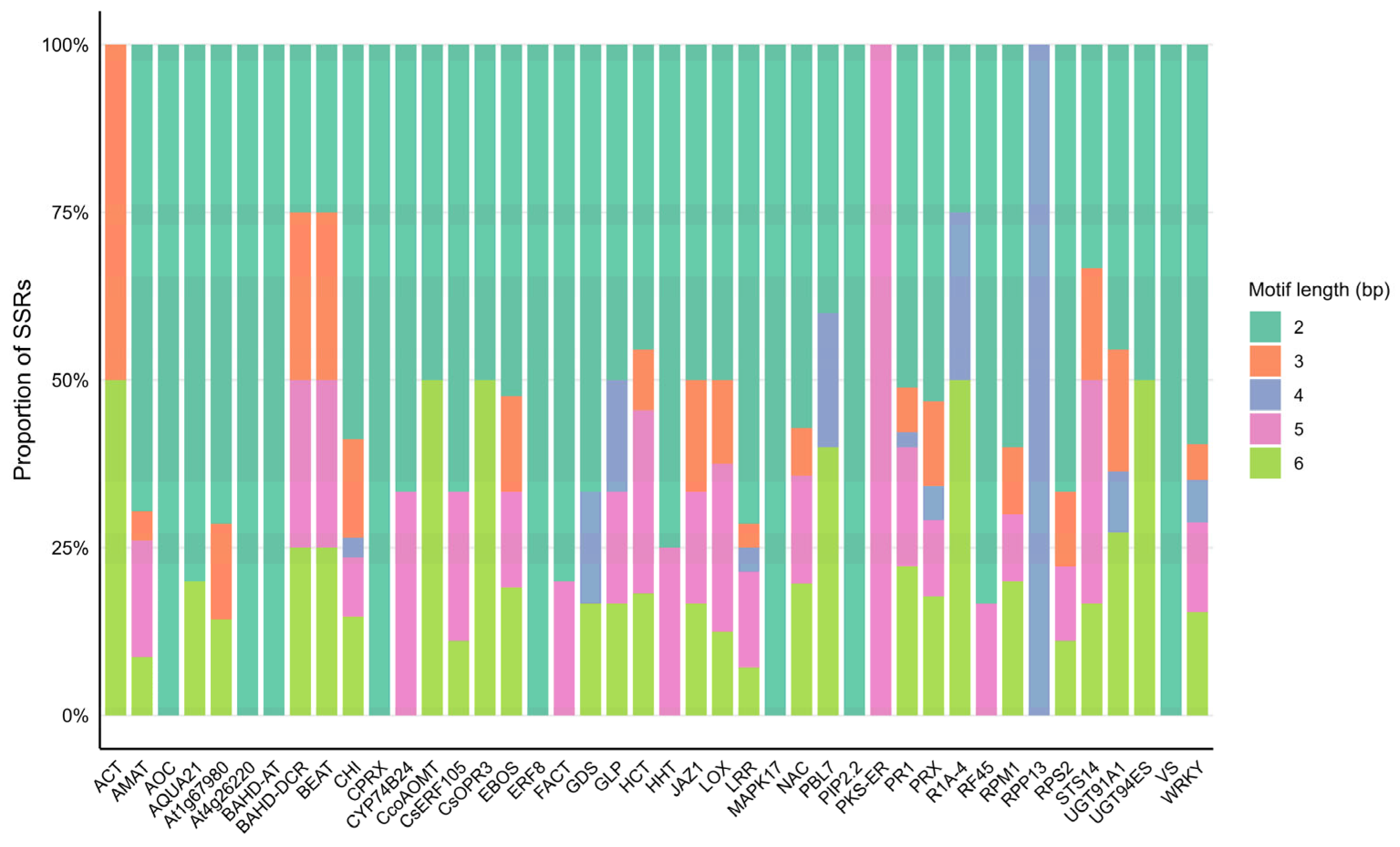

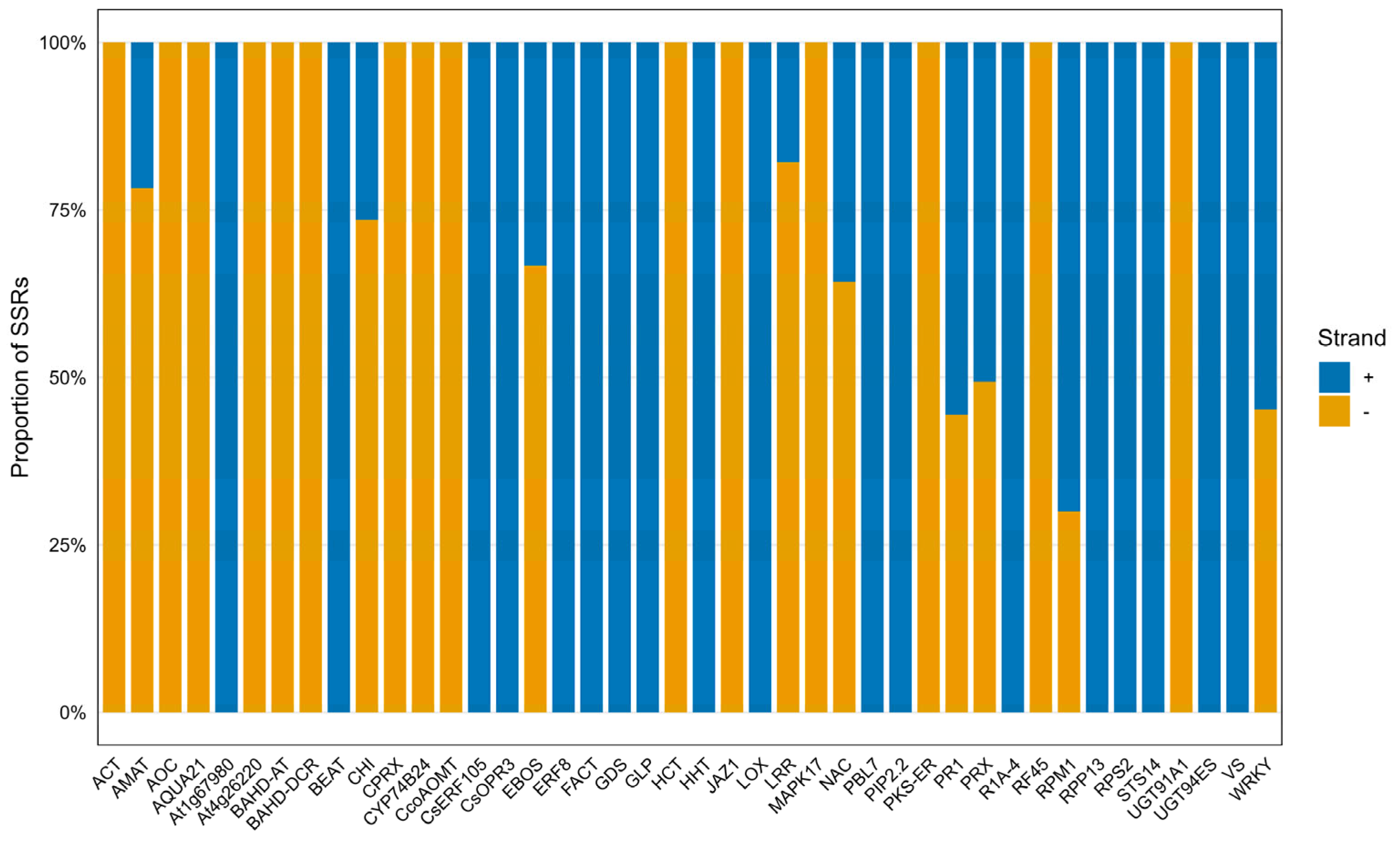

2.6. General Characteristics of the Developed SSR Primer Sets

2.7. In Silico PCR Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bioinformatics Tools and Packages

4.2. Literature-Based Selection of Disease Resistance–Associated Genes

4.3. Reference Genome Selection and Acquisition of Annotation Data

4.4. Mapping of SSR Motifs at Target Loci

4.5. Identification of Putative QTL Hotspot Regions

4.5.1. SSR Density-Based Detection of Putative QTL Hotspots

4.5.2. Selection and Prioritization of SSR Candidates Within pQTL Hotspot Regions

4.5.3. Machine Learning-Assisted Prioritization of SSR Motifs Associated with Chitinase, LRR, NAC, WRKY, and Peroxidase Genes

4.5.4. Random Forest Ablation Quantification; WRKY Example

4.5.5. Construction of Final SSR Marker Panels

4.6. Primer Design for Identified SSR Markers

4.7. In Silico PCR

4.8. Integrated Pipeline for pQTL-Guided and Machine Learning-Assisted SSR Marker Development

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, X.; Zhang, W.; Fernie, A.R.; Wen, W. Camellia sinensis (Tea). Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J.; Taniguchi, F. Tea. In Technical Crops. Genome Mapping and Molecular Breeding in Plants; Kole, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Shu, Z.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, S.; He, W. Metabolite Profiling and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal Defense Regulatory Network Against Pink Tea Mite Invasion in Tea Plant. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann-Danzinger, H. Diseases and Pests of Tea: Overview and Possibilities of Integrated Pest and Disease Management. J. Agric. Trop. Subtrop. 2000, 101, 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Majumder, S.; Ghosh, A.; Bhattacharya, M. Metabolomic Responses of Tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] Leaves to Red Spider Mite [Oligonychus coffeae (Nietner)] and Tea Mosquito Bug [Helopeltis theivora Waterhouse] Infestation: A GC–MS-Based Study. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Shan, W.; Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Su, F.; Yang, Z.; Yu, X. Defensive Responses of Tea Plants (Camellia sinensis) Against Tea Green Leafhopper Attack: A Multi-Omics Study. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Sinniah, G.D.; Babu, A.; Tanti, A. How the Global Tea Industry Copes with Fungal Diseases—Challenges and Opportunities. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1868–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Barooah, A.K.; Ahmed, K.Z.; Baruah, R.D.; Prasad, A.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Impact of Climate Change on Tea Pest Status in Northeast India and Effective Plans for Mitigation. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Cai, X.; Li, X.; Bian, L.; Luo, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xin, Z. (E)-Nerolidol Is a Volatile Signal That Induces Defenses Against Insects and Pathogens in Tea Plants. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Xu, J.; Wu, M.; Dai, X.; Xu, F.; Niu, S.; He, Y. Integrative Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Uncovers the Toxoptera aurantii (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Response of Two Camellia sinensis (Ericales: Theaceae) Cultivars. J. Econ. Entomol. 2025, 118, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Ma, L.; Cao, D.; Jin, X. Physiological and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal the Resistance Response Mechanism to Tea Aphid Infestation in New Shoots of Tea Plants (Camellia sinensis). Plant Stress 2024, 13, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, S.; Roy, C.; Ghosh, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Hazarika, L.K.; Chaudhuri, R.K.; Roy, S.; Chakraborti, D. Elicitation of Biomolecules as Host Defense Arsenals During Insect Attacks on Tea Plants (Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 7187–7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmah, S.R.; Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Barooah, A.K. Microbial Biocides—Viable Alternatives to Chemicals for Tea Disease Management. J. Biol. Control 2020, 34, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J.; Ge, S.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H.; Tang, M.; et al. Lignin Metabolism Is Crucial in the Plant Responses to Tambocerus elongatus (Shen) in Camellia sinensis L. Plants 2025, 14, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Qian, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Sun, X. Recent Advances in the Specialized Metabolites Mediating Resistance to Insect Pests and Pathogens in Tea Plants (Camellia sinensis). Plants 2024, 13, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lu, M.; Wu, Y.; Jing, T.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, T.; et al. Salicylic Acid Carboxyl Glucosyltransferase UGT87E7 Regulates Disease Resistance in Camellia sinensis. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 1507–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiboland, R. Environmental and Nutritional Requirements for Tea Cultivation. Folia Hortic. 2017, 29, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczyński, P.; Iwaniuk, P.; Jankowska, M.; Orywal, K.; Socha, K.; Perkowski, M.; Farhan, J.A.; Łozowicka, B. Pesticide residues in common and herbal teas combined with risk assessment and transfer to the infusion. Chemosphere 2024, 367, 143550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Rai, M.; Das, D.; Chandra, S.; Acharya, K. Blister blight: A threatened problem in tea industry—A review. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 3265–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Zhan, J.; Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xie, L.; He, D. Factors and minimal subsidy associated with tea farmers’ willingness to adopt ecological pest management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Lu, Q.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Sarkar, A. Measuring the impact of relative deprivation on tea farmers’ pesticide application behavior: The case of Shaanxi, Sichuan, Zhejiang, and Anhui Province, China. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Feng, H.; Yang, F.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, X.; Wei, C.; Liang, T.; Li, H.; Geng, Y. Does dual reduction in chemical fertilizer and pesticides improve nutrient loss and tea yield and quality? A pilot study in a green tea garden in Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 2464–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatoo, A.M.; Ali, M.N.; Baba, Z.A.; Hassan, B. Sustainable management of diseases and pests in crops by vermicompost and vermicompost tea: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-M.; Sun, X.-L.; Dong, W.-X. Genetics and chemistry of the resistance of tea plant to pests. In Global Tea Breeding; Chen, L., Apostolides, Z., Chen, Z.-M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 343–360. [Google Scholar]

- Mores, A.; Borrelli, G.M.; Laidò, G.; Petruzzino, G.; Pecchioni, N.; Amoroso, L.G.M.; Desiderio, F.; Mazzucotelli, E.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Marone, D. Genomic approaches to identify molecular bases of crop resistance to diseases and to develop future breeding strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Mahla, J.S.; Upadhyay, D.K.; Das, D.; Wankhade, M.; Kumar, M.; Lallawmkimi, M.C. Integration of genetic resistance mechanisms in sustainable crop breeding programs—A review. J. Adv. Biol. Biotechnol. 2025, 28, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Guo, N.; Wang, S.; Bai, J.; Yu, Y.; Liu, S. Identification of causal agent of gray blight disease in Camellia sinensis and screening of resistance cultivars. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisha, S.N.; Prabu, G.; Mandal, A.K.A. Biochemical and molecular studies on the resistance mechanisms in tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] against blister blight disease. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2018, 24, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Wen, D.; Liu, R.; Yao, X.; Chen, Z.; Mu, R.; Pei, H.; Liu, M.; Song, B.; et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly of Camellia sinensis combined with multi-omics provides insights into its responses to infestation with green leafhoppers. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1004387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.-Y.; Su, J.-J.; Zhang, C.-K.; Hao, M.; Zhou, Z.-W.; Chen, X.-H.; Zheng, S.-Z. Identification of key genes associated with anthracnose resistance in Camellia sinensis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Mei, P.; Ye, Y.; Liu, D.; Gong, Y.; Liu, H.; Yao, M.; Ma, C. QTL detection and candidate gene analysis of the anthracnose resistance locus in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 2240–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaswall, K.; Mahajan, P.; Singh, G.; Parmar, R.; Seth, R.; Raina, A.; Swarnkar, M.K.; Singh, A.K.; Shankar, R.; Sharma, R.K. Transcriptome analysis reveals candidate genes involved in blister blight defense in tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guo, N.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, S. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of pathogenesis-related 1 (PR-1) gene family in tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) in response to blister-blight disease stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Singh, G.; Seth, R.; Parmar, R.; Singh, P.; Singh, V.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, R.K. Functional annotation and characterization of hypothetical protein involved in blister blight tolerance in tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze). J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Yang, C.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z. Transcriptome and co-expression network analysis uncover the key genes mediated by endogenous defense hormones in tea plant in response to the infestation of Empoasca onukii Matsuda. Beverage Plant Res. 2023, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Yang, C.; Mi, X.; Tang, M.; Liang, S.; Chen, Z. Genome-wide identification of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) BAHD acyltransferases reveals their role in response to herbivorous pests. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geethanjali, S.; Kadirvel, P.; Anumalla, M.; Hemanth Sadhana, N.; Annamalai, A.; Ali, J. Streamlining of simple sequence repeat data mining methodologies and pipelines for crop scanning. Plants 2024, 13, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.S. SSR genotyping. In Plant Genotyping: Methods and Protocols; Mason, A.S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tillault, A.; Yevtushenko, D.P. Simple sequence repeat analysis of new potato varieties developed in Alberta, Canada. Plant Direct 2019, 3, e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Shu, G.; Hu, Y.; Cao, G.; Wang, Y. Pattern and variation in simple sequence repeat (SSR) at different genomic regions and its implications to maize evolution and breeding. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batashova, M.; Kryvoruchko, L.; Makaova-Melamud, B.; Tyshchenko, V.; Spanoghe, M. Application of SSR markers for assessment of genetic similarity and genotype identification in local winter wheat breeding program. Stud. Biol. 2024, 18, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Qiu, J.; Agarwal, G.; Wang, J.; Ren, X.; Xia, H.; Guo, B.; Ma, C.; Wan, S.; Bertioli, D.J.; et al. Genome-wide discovery of microsatellite markers from diploid progenitor species, Arachis duranensis and A. ipaensis, and their application in cultivated peanut (A. hypogaea). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, D.; Sari, H.; Ikten, C.; Toker, C. Genome-wide discovery of di-nucleotide SSR markers based on whole genome re-sequencing data of Cicer arietinum L. and Cicer reticulatum Ladiz. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Miao, L.; Zou, M.; Hussain, I.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Sun, N.; Kong, L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; et al. Development of SSRs based on the whole genome and screening of bolting-resistant SSR marker in Brassica oleracea L. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuki, Z.M.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ramli, A.; Oladosu, Y.; Latif, M.A.; Sijam, K.; Ismail, M.R.; Sarif, H.M. Segregation analysis for bacterial leaf blight disease resistance genes in rice ‘MR219′ using SSR marker. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 80, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi Holasou, H.; Panahi, B.; Shahi, A.; Nami, Y. Integration of machine learning models with microsatellite markers: New avenue in world grapevine germplasm characterization. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 38, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Yang, Q.; Bai, Y.; Gong, K.; Wu, T.; Yu, T.; Pei, Q.; Duan, W.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of SSRs and database construction using all complete gene-coding sequences in major horticultural and representative plants. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureshkumar, S.; Chhabra, A.; Guo, Y.; Balasubramanian, S. Simple sequence repeats and their expansions: Role in plant development, environmental response and adaptation. New Phytol. 2025, 247, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portis, E.; Lanteri, S.; Barchi, L.; Portis, F.; Valente, L.; Toppino, L.; Rotino, G.L.; Acquadro, A. Comprehensive characterization of simple sequence repeats in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) genome and construction of a web resource. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.J.; Ahmadikhah, A. Occurrence of simple sequence repeats in cDNA sequences of safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) reveals the importance of SSR-containing genes for cell biology and dynamic response to environmental cues. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 991107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ge, L.; Lei, S.; Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Sun, X. A putative 12-oxophytodienoate reductase gene CsOPR3 from Camellia sinensis is involved in wound and herbivore infestation responses. Gene 2017, 615, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xi, L.; Fu, N. Genome-wide development of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers at 2-Mb intervals in lotus (Nelumbo Adans.). BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, J.; Sun, W.; Li, H.; Li, D.; Zhuge, Q. Characteristics and function of the pathogenesis-related protein 1 gene family in poplar. Plant Sci. 2023, 336, 111857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Luo, C.; Yang, X.; Peng, L.; Lu, T.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, F.; et al. Genome-wide identification of the mango pathogenesis-related 1 (PR1) gene family and functional analysis of MiPR1A genes in transgenic Arabidopsis. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 321, 112254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, T.; Wang, W.; Sun, T.; Shen, L.; Feng, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S. Pathogenesis-related 1 (PR1) protein family genes involved in sugarcane responses to Ustilago scitaminea stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meteignier, L.-V.; el Oirdi, M.; Cohen, M.; Barff, T.; Matteau, D.; Lucier, J.-F.; Rodrigue, S.; Jacques, P.-E.; Yoshioka, K.; Moffett, P. Translatome analysis of an NB-LRR immune response identifies important contributors to plant immunity in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caicedo, A.L.; Schaal, B.A.; Kunkel, B.N. Diversity and molecular evolution of the RPS2 resistance gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Zhang, X.; Bent, A.F. The leucine-rich repeat domain can determine effective interaction between RPS2 and other host factors in Arabidopsis RPS2-mediated disease resistance. Genetics 2001, 158, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cao, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Recent advances in functional assays of WRKY transcription factors in plant immunity against pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1517595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, K.K.; Kuo, S.-Y.; Tu, C.-W.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-W.; Hu, C.-C. The role of plant transcription factors in the fight against plant viruses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.-H.; Zoclanclounon, Y.A.B.; Park, G.-H.; Lee, J.-D.; Kim, T.-H. Genome-wide in silico analysis of leucine-rich repeat R-genes in Perilla citriodora: Classification and expression insights. Genes 2025, 16, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marone, D.; Russo, M.; Laidò, G.; De Leonardis, A.; Mastrangelo, A. Plant nucleotide binding site–leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes: Active guardians in host defense responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7302–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Meyers, B.C.; Chen, J.; Tian, D.; Yang, S. Tracing the origin and evolutionary history of plant nucleotide-binding site–leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, L.H.; Fehr, B.; Chobirko, J.D.; Moghe, G.D. Phylogenomic analyses across land plants reveals motifs and coexpression patterns useful for functional prediction in the BAHD acyltransferase family. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1067613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhuang, W.; Wang, T.; Xie, Y. Family characteristics, phylogenetic reconstruction, and potential applications of the plant BAHD acyltransferase family. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1218914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biniaz, Y.; Tahmasebi, A.; Tahmasebi, A.; Albrectsen, B.R.; Poczai, P.; Afsharifar, A. Transcriptome meta-analysis identifies candidate hub genes and pathways of pathogen stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biology 2022, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharabli, H.; Della Gala, V.; Welner, D.H. The function of UDP-glycosyltransferases in plants and their possible use in crop protection. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 67, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Shah, Z.H.; Ludwig-Müller, J.; Chung, G.; Ahmad, M.Q.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, S.I. Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses of family-1 UDP glycosyltransferase in three Brassica species and Arabidopsis indicates stress-responsive regulation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2025. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit Software; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2025; Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Ma, J.-Q.; Yao, M.-Z.; Ma, C.-L.; Wang, X.-C.; Jin, J.-Q.; Wang, X.-M.; Chen, L. Construction of a SSR-based genetic map and identification of QTLs for catechins content in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eminoğlu, A.; İzmirli, Ş.G.; Beriş, F.Ş.; Dinçer, D.; Yazıcı, K. SSR genotyping of 200 tea (Camellia sinensis) clones obtained by selection and DNA barcoding of 12 varietal registration candidates. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene, Protein Family | Biological Function/Role (*) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CsOPR3 | 12-oxophytodienoate reductase; jasmonic acid biosynthesis pathway | [9] |

| RPP13 | RPM1 gene | [3] |

| RF45 | RPM1 gene | [3] |

| R1A-4 | RPM1 gene | [3] |

| RPM1 | RPM1 gene | [3] |

| UGT91A1 | Flavonoid precursor | [3] |

| UGT94ES | Flavonoid precursor | [3] |

| At4g26220 | Flavonoid precursor | [3] |

| At1g67980 | Flavonoid precursor | [3] |

| PBL7 | A0A4S4DNL6 | [29] |

| GLP | A0A4S4EHC7 | [29] |

| LOX | A0A4S4EI95 | [29] |

| CcoAOMT | A0A4V3WNP8 | [29] |

| PKS-ER | A0A4V3WQ16 | [29] |

| CYP74B24 | A0A4S4E216 | [29] |

| CsERF105 | A nuclear-localized Ethylene-responsive transcription factor | [31] |

| RPS2 | Resistance protein (NBS-LRR); pathogen recognition and defense activation | [32] |

| BEAT | BAHD acyltransferase | [32] |

| PR1 | Pathogenesis-related protein 1; marker for systemic acquired resistance | [33] |

| STS14 | PR1 | [33] |

| Chitinase | Hydrolyzes chitin in fungal cell walls; key enzyme in plant defense | [34] |

| Peroxsidase | Involved in reactive oxygen species detoxification and pathogen defense | [34] |

| NAC | Transcription factor regulating stress responses and development | [34] |

| LRR | Leucine-rich repeat domain involved in protein–protein interactions, commonly in resistance proteins | [34] |

| WRKY | Transcription factor family regulating pathogen and abiotic stress responses | [34] |

| EBOS | Terpene synthase | [35] |

| GDS | Terpene synthase | [35] |

| MAPK17 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase; signal transduction in stress and defense pathways | [35] |

| AQUA21 | Aquaporin | [35] |

| PIP2.2 | Aquaporin | [35] |

| JAZ1 | Jasmonate-zim-domain protein | [35] |

| CPRX | Cationic peroxidase | [35] |

| ERF8 | CsERF | [35] |

| AMAT | BAHD acyltransferase | [36] |

| HHT | BAHD acyltransferase | [36] |

| BAHD-AT | BAHD acyltransferase | [36] |

| HCT | BAHD acyltransferase | [36] |

| BAHD-DCR | BAHD acyltransferase | [36] |

| FACT | BAHD acyltransferase | [36] |

| ACT | BAHD acyltransferase | [36] |

| VS | BAHD acyltransferase | [36] |

| Assembly | GenBank | Scientific Name | Cultivar |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHAU_CSS_1 | GCA_004153795.1 | Camellia sinensis | Shuchazao |

| ASM1731120v1 | GCA_017311205.1 | Camellia sinensis var. sinensis | Tieguanyin |

| IND_Tea_TV1 | GCA_028456175.1 | Camellia sinensis var. assamica | TV1 |

| ASM2053679v1 | GCA_020536795.1 | Camellia sinensis var. assamica | TES-34 |

| Camellia sinensis L618 reference annotation | GCA_963931755.2 | Camellia sinensis | |

| ASM2053686v1 | GCA_020536865.1 | Camellia sinensis var. assamica | UPASI-3 |

| Pathogen and Pest | Number of Loci | Number of Markers | Single-Product Markers | Multi-Product Markes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colletotrichum fructicola | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Empoasca onukii | 12 | 33 | 9 | 24 |

| Empoasca vitis | 6 | 15 | 6 | 9 |

| Exobasidium vexans | 154 | 278 | 105 | 173 |

| Acaphylla theae | 8 | 22 | 6 | 16 |

| Ectropis obliqua | 13 | 31 | 14 | 17 |

| Colletotrichum camelliae | 1 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Parameter | Setting (Value) |

|---|---|

| Analysis region (locus ± flanking) | ±5000 bp |

| Motif lengths | 2–6 bp |

| Minimum repeat threshold | k = 2:≥8; k = 3:≥5; k = 4:≥4; k = 5–6:≥3 |

| Sliding window size | 1000 bp |

| Window step size | 500 bp (offsets: 0 and 500 bp) |

| Number of permutations | 1000 |

| Hotspot significance threshold | 95% and 99%; final panel: 99% |

| Handling of σ = 0 cases | Z-score set to NA; Z not calculated; excluded from hotspot calling |

| Random Forest settings | ranger; 70/30 train-test split; 1000 trees; mtry = 3; probability = TRUE; importance = node purity; high-confidence cutoff: prob_pos ≥ 0.70 |

| Primer length | 18–20 bp |

| Tm | 50–65 °C |

| GC ratio | 35–65% |

| Amplicon size | 100–400 bp |

| Primer flanking region | ±200 bp |

| Mismatch (in silico PCR) | 0 |

| Max amplicon (in silico PCR): | 1000 bp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eminoğlu, A. Identification and Development of Pathogen- and Pest-Specific Defense–Resistance-Associated SSR Marker Candidates Assisted by Machine Learning and Discovery of Putative QTL Hotspots in Camellia sinensis. Plants 2026, 15, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030454

Eminoğlu A. Identification and Development of Pathogen- and Pest-Specific Defense–Resistance-Associated SSR Marker Candidates Assisted by Machine Learning and Discovery of Putative QTL Hotspots in Camellia sinensis. Plants. 2026; 15(3):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030454

Chicago/Turabian StyleEminoğlu, Ayşenur. 2026. "Identification and Development of Pathogen- and Pest-Specific Defense–Resistance-Associated SSR Marker Candidates Assisted by Machine Learning and Discovery of Putative QTL Hotspots in Camellia sinensis" Plants 15, no. 3: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030454

APA StyleEminoğlu, A. (2026). Identification and Development of Pathogen- and Pest-Specific Defense–Resistance-Associated SSR Marker Candidates Assisted by Machine Learning and Discovery of Putative QTL Hotspots in Camellia sinensis. Plants, 15(3), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030454