Comparative Analysis of Insect Resistance in Transgenic Populus × euramericana cv. Neva Expressing Dual Bt Genes from Different Sources

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. PCR Detection of Exogenous Genes in Transgenic Lines

2.2. Analysis and Validation of Exogenous Gene Insertion Sites in Transgenic Lines

2.3. Analysis of Exogenous Gene Expression in Transgenic Lines

2.4. Insect Resistance Assessment of Transgenic Lines

2.4.1. Analysis of Resistance to H. cunea in Transgenic Lines

Analysis of Resistance Against 1st-Instar H. cunea Larvae

Analysis of Resistance Against 3rd-Instar H. cunea Larvae

2.4.2. Analysis of Resistance Against P. versicolora in Transgenic Lines

2.4.3. Analysis of Resistance Against A. glabripennis in Transgenic Lines

2.5. Transcription Response of P. versicolora Larvae to Bt Toxin

2.5.1. Differential Gene Identification and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis in Larvae

2.5.2. GO Functional Enrichment and KEGG Pathway Annotation of Larval Genes

2.5.3. Transcription Factor Analysis in Larvae

2.5.4. qRT-PCR Validation of Larval Gene Expression

2.5.5. Screening of Larval Development and Bt-Related Genes in P. versicolora

Proteases Involved in Bt protoxin Activation and Digestion in Larvae

Differential Genes Associated with Potential Bt toxin Receptor Proteins in Larvae

Genes Associated with Detoxification Enzyme Systems in Larvae

Differentially Expressed Genes Associated with Larval Growth and Development

3. Discussion

3.1. Variations in Exogenous Gene Expression and Insect Resistance Among Transgenic Lines

3.2. Transgenic Lines Exhibited Differential Insecticidal Efficacy Against the Two Coleopteran Species

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Insect Resistance Conferred by Different Vector Constructs

3.4. Transcriptomic Response of P. versicolora Larvae to Bt Toxin

3.5. Research Summary and Future Directions for Application

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. PCR and qRT-PCR Detection of Exogenous Genes in Transgenic Lines

4.3. Analysis of T-DNA Insertion Sites and Bt Toxin Detection in Transgenic Lines

4.4. Insect Resistance Assessment of Transgenic Lines—Insect Feeding Bioassay/Calculation Methods

- (1)

- H. cunea

- (2)

- P. versicolora

- (3)

- A. glabripennis

4.5. Transcriptome Sequencing and qRT-PCR Validation of P. versicolora Larvae

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanahuja, G.; Banakar, R.; Twyman, R.M.; Capell, T.; Christou, P. Bacillus thuringiensis: A century of research, development and commercial applications. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011, 9, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-Z.; Cao, J.; Li, Y.; Collins, H.L.; Roush, R.T.; Earle, E.D.; Shelton, A.M. Transgenic plants expressing two Bacillus thuringiensis toxins delay insect resistance evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1493–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, F.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C. The Sustainability of the Farm-level Impact of Bt Cotton in China. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 67, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, S.; Liu, B.; Gao, Y.; Hu, C.; Li, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; et al. Bt maize can provide non-chemical pest control and enhance food safety in China. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, T.R.; Bonsall, M.B. Combining refuges with transgenic insect releases for the management of an insect pest with non-recessive resistance to Bt crops in agricultural landscapes. J. Theor. Biol. 2021, 509, 110514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, V. From microbial sprays to insect-resistant transgenic plants: History of the biospesticide Bacillus thuringiensis. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 31, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouzani, G.S.; Valijanian, E.; Sharafi, R. Bacillus thuringiensis: A successful insecticide with new environmental features and tidings. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 2691–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhong, J.; Wen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Q.; Yu, X.-Q.; Lu, Y. Genome-wide identification and comparative analysis of Cry toxin receptor families in 7 insect species with a focus on Spodoptera litura. Insect Sci. 2022, 29, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, M.; Rodriguez-Almazán, C.; Muñóz-Garay, C.; Pardo-López, L.; Porta, H.; Bravo, A. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt mutants useful to counter toxin action in specific environments and to overcome insect resistance in the field. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 104, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.; Rajadurai, G.; Mohankumar, S.; Balakrishnan, N.; Raghu, R.; Balasubramani, V.; Sivakumar, U. Interactions between insecticidal cry toxins and their receptors. Curr. Genet. 2025, 71, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinos, D.; Millán-Leiva, A.; Ferré, J.; Hernández-Martínez, P. New Paralogs of the Heliothis virescens ABCC2 Transporter as Potential Receptors for Bt Cry1A Proteins. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ferry, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Edwards, M.G.; Gatehouse, A.M.R.; He, K. A proteomic approach to study the mechanism of tolerance to Bt toxins in Ostrinia furnacalis larvae selected for resistance to Cry1Ab. Transgenic Res. 2013, 22, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Villanueva, M.; Muruzabal-Galarza, A.; Fernández, A.B.; Unzue, A.; Toledo-Arana, A.; Caballero, P.; Caballero, C.J. Bacillus thuringiensis Cyt Proteins as Enablers of Activity of Cry and Tpp Toxins against Aedes albopictus. Toxins 2023, 15, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, D.; Bel, Y.; Menezes de Moura, S.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Grossi de Sa, M.F.; Robles-Fort, A.; Escriche, B. Distinct Impact of Processing on Cross-Order Cry1I Insecticidal Activity. Toxins 2025, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-López, L.; Gómez, I.; Rausell, C.; Sánchez, J.; Soberón, M.; Bravo, A. Structural Changes of the Cry1Ac Oligomeric Pre-Pore from Bacillus thuringiensis Induced by N-Acetylgalactosamine Facilitates Toxin Membrane Insertion. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 10329–10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzaro, M.D.; Padilha, I.; Ramos, L.F.C.; Mendez, A.P.G.; Menezes, A.; Silva, Y.M.; Martins, M.R.; Junqueira, M.; Nogueira, F.C.S.; AnoBom, C.D.; et al. Cry1Ac toxin binding in the velvetbean caterpillar Anticarsia gemmatalis: Study of midgut aminopeptidases N. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1484489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Bulla, L.A. Commentary: Analyzing invertebrate bitopic cadherin G protein-coupled receptors that bind Cry toxins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 272, 110963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Almanza, G.; Esparza-Ibarra, E.L.; Ayala-Luján, J.L.; Mercado-Reyes, M.; Godina-González, S.; Hernández-Barrales, M.; Olmos-Soto, J. The Cytocidal Spectrum of Bacillus thuringiensis Toxins: From Insects to Human Cancer Cells. Toxins 2020, 12, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Chen, L.; Cheng, H.H.; Zhao, Y.H.; Wu, Y.Q.; Li, Y.G.; Wu, Y.J. Analysis of genetic and expression stability of exogenous genes in transgenic apple during long-term subculture. J. China Agric. Univ. 2020, 25, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Ren, Y.; Du, K.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Effect of T-DNA Integration on Growth of Transgenic Populus × euramericana cv. Neva Underlying Field Stands. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

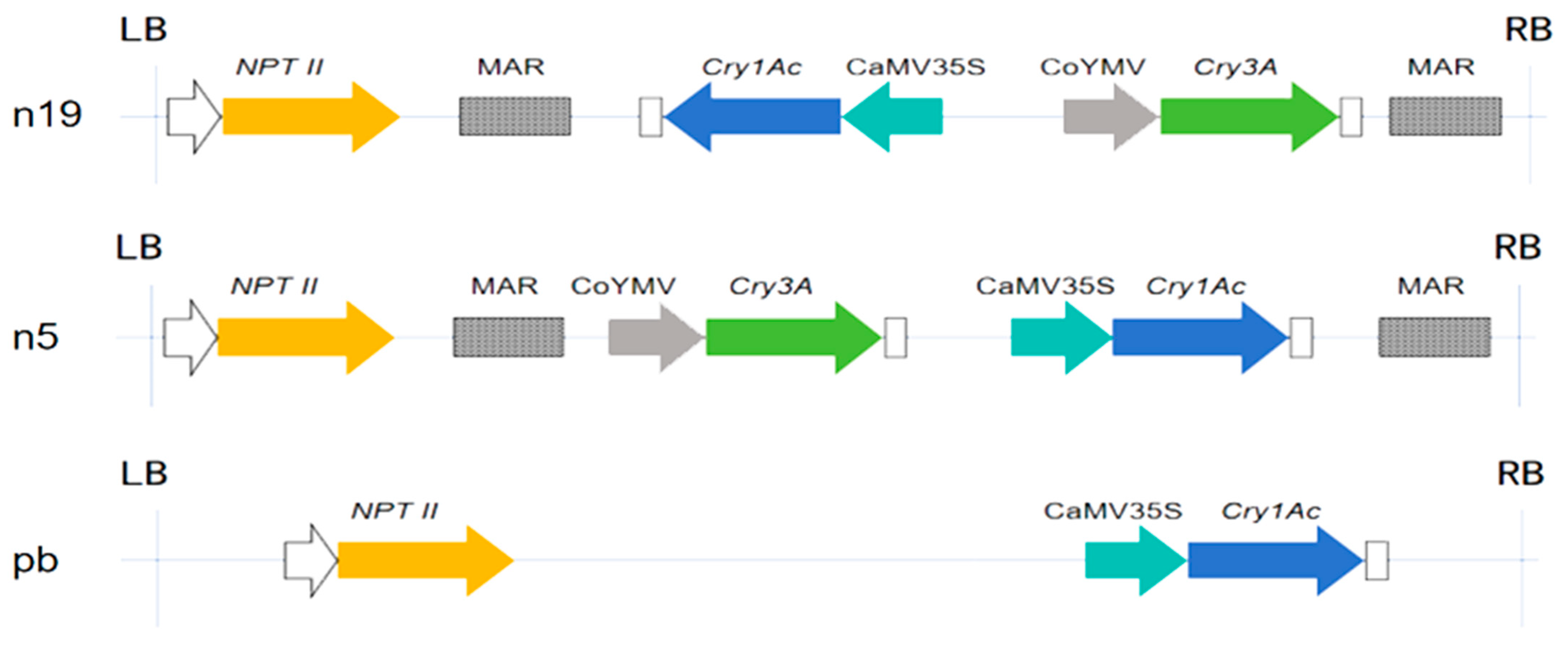

- Qiu, T.; Dong, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J. Effects of the sequence and orientation of an expression cassette in tobacco transformed by dual Bt genes. Plasmid 2017, 89, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butel, N.; Yu, A.; Le Masson, I.; Borges, F.; Elmayan, T.; Taochy, C.; Gursanscky, N.R.; Cao, J.; Bi, S.; Sawyer, A.; et al. Contrasting epigenetic control of transgenes and endogenous genes promotes post-transcriptional transgene silencing in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, P.; Li, X.; Li, R.; Yang, L. A paired-end whole-genome sequencing approach enables comprehensive characterization of transgene integration in rice. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrikeski, P.T. Insertion orientation within the cassette affects gene-targeting success during ends-out recombination in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 2022, 68, 551–564. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.L.; Choi, M.; Jung, K.-H.; An, G. Analysis of the early-flowering mechanisms and generation of T-DNA tagging lines in Kitaake, a model rice cultivar. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4169–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fu, T.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Yu, R.; Ji, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; et al. Identification and characterization of miRNAs and targets in two poplar varieties with different resistance in responses to Anoplophora glabripennis (Coleoptera) infestation. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Zhou, L.Y.; Wang, G.F.; Du, Z.G.; Zhou, X.H. Problems and countermeasures caused by high-proportion pure plantations in central and southeast China. J. Terr. Ecosyst. Conserv. 2022, 2, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, J.; Liang, H.; Yang, M. Expression of Exogenous Genes in Transgenic Populus × euramericana ‘Neva’ with Two Insect-Resistant Genes. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2015, 51, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Meng, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Long, L.; Wu, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Title: Transcriptome-assisted optimization of adventitious bud induction from field-grown stem segments to enhance genetic transformation of Poplar 107 (Populus × euramericana cv. Neva). Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 238, 122291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhou, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Exogenous Gene Expression and Insect Resistance in Dual Bt Toxin Populus × euramericana ‘Neva’ Transgenic Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 660226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhen, Z.; Cui, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, M.; Wu, J. Growth and arthropod community characteristics of transgenic poplar 741 in an experimental forest. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 162, 113284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiao, D.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Y. Advances and Perspectives of Transgenic Technology and Biotechnological Application in Forest Trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 786328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimase, M.; Brown, S.; Head, G.P.; Price, P.A.; Walker, W.; Yu, W.; Huang, F. Performance of Bt-susceptible and -heterozygous dual-gene resistant genotypes of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in seed blends of non-Bt and pyramided Bt maize. Insect Sci. 2021, 28, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wei, H.; Wang, L.; Yin, T.; Zhuge, Q. Optimization of the cry1Ah1 Sequence Enhances the Hyper-Resistance of Transgenic Poplars to Hyphantria cunea. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yue, Q.; Miao, L.; Li, S.; Tian, J.; Si, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. A novel nucleic acid linker for multi-gene expression enhances plant and animal synthetic biology. Plant J. 2024, 118, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.-Y.; Guo, Z.-H.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Han, C.-G.; Wang, Y. Development of Beet necrotic yellow vein virus-based vectors for multiple-gene expression and guide RNA delivery in plant genome editing. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1302–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.-W.; Liu, G.-F.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Yan, S.-C.; Ma, L.; Yang, C.-P. Response of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar to transgenic poplar, Populus simonii × P. nigra, expressing fusion protein gene of the spider insecticidal peptide and Bt-toxin C-peptide. J. Insect Sci. 2010, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, F.E.; Sathe, S.; Wheeler, E.C.; Yeo, G.W. Non-microRNA binding competitively inhibits LIN28 regulation. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fialcowitz, E.J.; Brewer, B.Y.; Keenan, B.P.; Wilson, G.M. A hairpin-like structure within an AU-rich mRNA-destabilizing element regulates trans-factor binding selectivity and mRNA decay kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 22406–22417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaev, D.; Abdelmessih, M.; Vejnar, C.E.; Yartseva, V.; Weiss, L.A.; Strayer, E.C.; Takacs, C.M.; Giraldez, A.J. UPF1 regulates mRNA stability by sensing poorly translated coding sequences. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, D.; Sturgill, D.; Alhusaini, N.; Dillman, A.A.; Sweet, T.J.; Hanson, G.; Hosogane, M.; Sinclair, W.R.; Nanan, K.K.; Mandler, M.D.; et al. Acetylation of Cytidine in mRNA Promotes Translation Efficiency. Cell 2018, 175, 1872–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbemafle, W.; Wong, M.M.; Bassham, D.C. Transcriptional and post-translational regulation of plant autophagy. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 6006–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Su, X.H.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.A.; Qu, L.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Tian, Y.C. Acquisition of transgenic Populus alba × P. glandulosa with coleopteran-resistant gene and its primary insect resistance evaluation. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2006, 28, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zuo, Y.-Y.; Li, L.-L.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.-Y.; Yang, Y.-H.; Wu, Y.-D. Knockout of three aminopeptidase N genes does not affect susceptibility of Helicoverpa armigera larvae to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A and Cry2A toxins. Insect Sci. 2020, 27, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, D.J.; Hallaway, M. Auxin Control of Protein-Levels in Detached Autumn Leaves. Nature 1960, 188, 240–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Gao, B. Genetic transformation and expression of Cry1Ac–Cry3A–NTHK1 genes in Populus × euramericana “Neva”. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Niu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.; Head, G.P.; Price, P.A.; Wen, X.; Huang, F. Survival and effective dominance level of a Cry1A.105/Cry2Ab2-dual gene resistant population of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) on common pyramided Bt corn traits. Crop Prot. 2019, 115, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daves, C.A.; Williams, W.P.; Davis, F.M.; Baker, G.T.; Ma, P.W.K.; Monroe, W.A.; Mohan, S. Plant resistance and its effect on the Peritrophic membrane of southwestern corn borer (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) larvae. J. Econ. Entomol. 2007, 100, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibaee, A.; Hajizadeh, J. Proteolytic activity in Plagiodera versicolora Laicharting (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): Characterization of digestive proteases and effect of host plants. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2013, 16, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Mu, Y.; Xu, J.; Huang, X.; Li, L. Formyl-phloroglucinol meroterpenoids with Nrf2 inhibitory activity from Eucalyptus globulus leaves. Phytochemistry 2025, 235, 114457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppert, B.; Dowd, S.E.; Bouffard, P.; Li, L.; Conesa, A.; Lorenzen, M.D.; Toutges, M.; Marshall, J.; Huestis, D.L.; Fabrick, J.; et al. Transcriptome Profiling of the Intoxication Response of Tenebrio molitor Larvae to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3Aa Protoxin. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, Z. Midgut transcriptomal response of the rice leaffolder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Guenée) to Cry1C toxin. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Meihls, L.N.; Hibbard, B.E.; Ji, T.; Elsik, C.G.; Shelby, K.S. Differential gene expression in response to eCry3.1Ab ingestion in an unselected and eCry3.1Ab-selected western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) population. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikhedkar, N.; Summanwar, A.; Joshi, R.; Giri, A. Cathepsins of lepidopteran insects: Aspects and prospects. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 64, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Ziling, C.; Huajun, W.; Linlin, L. Changes in Midgut Gene Expression Following Bacillus thuringiensis (Bacillales: Bacillaceae) Infection in Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Fla. Entomol. 2016, 99, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y. Functional validation of cadherin as a receptor of Bt toxin Cry1Ac in Helicoverpa armigera utilizing the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 76, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, L.C.; Siegfried, B.D.; Gassmann, A.J.; Wang, H.; Brewer, G.J.; Miller, N.J. Investigation of Cry3Bb1 resistance and intoxication in western corn rootworm by RNA sequencing. J. Appl. Entomol. 2018, 142, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Fu, Y.; Pan, D.; Zhan, E.; Li, Y. APN3 Acts as a Functional Receptor of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac in Grapholita molesta. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 13393–13404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhu, L.; Guo, L.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; Crickmore, N.; Zhou, X.; Bravo, A.; Soberón, M.; Guo, Z.; et al. A versatile contribution of both aminopeptidases N and ABC transporters to Bt Cry1Ac toxicity in the diamondback moth. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Hussain, K.; Liu, N.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Yang, S. Ecotoxicity of Cadmium along the Soil-Cotton Plant-Cotton Bollworm System: Biotransfer, Trophic Accumulation, Plant Growth, Induction of Insect Detoxification Enzymes, and Immunocompetence. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 14326–14336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, B.-M.; Han, J.; Lee, J.-S. Identification of 74 cytochrome P450 genes and co-localized cytochrome P450 genes of the CYP2K, CYP5A, and CYP46A subfamilies in the mangrove killifish Kryptolebias marmoratus. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Z.; Luo, L.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Z.; Luo, T.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y. An aldo-keto reductase, Bbakr1, is involved in stress response and detoxification of heavy metal chromium but not required for virulence in the insect fungal pathogen, Beauveria bassiana. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2018, 111, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, Z.; Dong, L.; Guo, L.; Bai, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Xie, W.; et al. A midgut transcriptional regulatory loop favors an insect host to withstand a bacterial pathogen. Innovation 2024, 5, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.-J.; Zhu, F.; Liu, Y.-J.; Li, Z.; Moural, T.W.; Liu, X.-M.; Liu, X. MicroRNAs miR-14 and miR-2766 regulate tyrosine hydroxylase to control larval-pupal metamorphosis in Helicoverpa armigera. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 3540–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkittichote, P.; Ah Mew, N.; Chapman, K.A. Propionyl-CoA carboxylase—A review. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 122, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, C.; Wei, L.; Jian, S.; Liu, N. Transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals key genes and secondary metabolites of Casuarina equisetifolia ssp. incana in response to drought stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparast, M.; Park, Y. Differential Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Genes Related to Low- and High-Temperature Stress in the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, 827077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabu, S.; Jing, D.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Wang, Z.; He, K. Hemocyte response to treatment of susceptible and resistant Asian corn borer (Ostrinia furnacalis) larvae with Cry1F toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1022445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vector | Line | Chromosome | Insertion Site | Insertion Type | Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n19 | n19a | Chr2 | 4,814,040 | Paired-end | Reverse |

| n19b | Chr5 | 20,284,755 | RB | Forward | |

| pb | pb8 | Chr10 | 2,683,280 | LB | Forward |

| pb9 | Chr11 | 4,359,721 | LB | Forward | |

| n5 | DB16 | Chr1 | 30,504,409 | Paired-end | Reverse |

| Chr12 | 14,365,239 | Paired-end | Tandem Repeat (Forward-Reverse) | ||

| Chr17 | 13,926,822 | Paired-end | Reverse | ||

| DB7 | Chr10 | 344,937 | LB | Forward | |

| Chr10 | 21,796,805 | RB | Reverse |

| Genes | WT vs. n19a | WT vs. DB16 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up | Down | Total | Up | Down | Total | |

| Bt prototoxin activation and digestion-related protease | ||||||

| Trypsin | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Serine protease | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cathepsin | 14 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Carboxypeptidase | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lipase | 2 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Polygalacturonase | 15 | 0 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Potential Bt-binding receptors | ||||||

| Cadherin | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Aminopeptidase N | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Detoxification enzymes | ||||||

| GST | 3 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| CYP450 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UGT | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| AKR | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Growth and development | ||||||

| Eif4ebp1(4E-BP1) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| CDK12,CDK13 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RRM1(RNRM1) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| GFPT1(GFAT) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MTEFMT | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PCCB | 16 | 4 | 20 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| ACP5(TRAP) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Yan, X.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Comparative Analysis of Insect Resistance in Transgenic Populus × euramericana cv. Neva Expressing Dual Bt Genes from Different Sources. Plants 2026, 15, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010051

Li J, Zhang J, Li H, Wang C, Yan X, Ren Y, Wang J, Yang M. Comparative Analysis of Insect Resistance in Transgenic Populus × euramericana cv. Neva Expressing Dual Bt Genes from Different Sources. Plants. 2026; 15(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jialu, Jiali Zhang, Hongrui Li, Chunyu Wang, Xue Yan, Yachao Ren, Jinmao Wang, and Minsheng Yang. 2026. "Comparative Analysis of Insect Resistance in Transgenic Populus × euramericana cv. Neva Expressing Dual Bt Genes from Different Sources" Plants 15, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010051

APA StyleLi, J., Zhang, J., Li, H., Wang, C., Yan, X., Ren, Y., Wang, J., & Yang, M. (2026). Comparative Analysis of Insect Resistance in Transgenic Populus × euramericana cv. Neva Expressing Dual Bt Genes from Different Sources. Plants, 15(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010051