Protein Post-Translational Modifications in Plant Abiotic Stress Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Main Types of Post-Translational Modifications

2.1. Phosphorylation

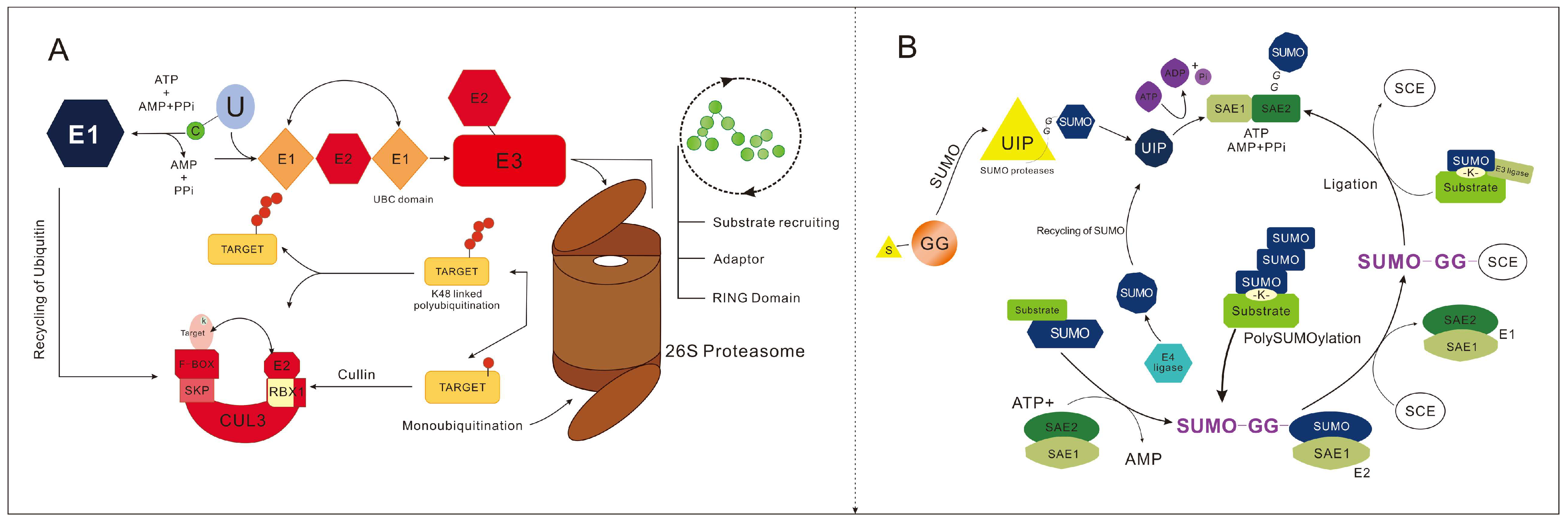

2.2. Ubiquitination

2.3. SUMOylation

2.4. Glycosylation

2.5. Methylations

2.6. Acetylation

2.7. S-Nitrosylation

2.8. Other PTMs

| Types of PTM | Modified Amino Acid Residue | Number of Proteins with Modifications | Main Functions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation | S, T, Y, D, N-term | 82,207 | Plant growth and development, response to abiotic/biotic stresses, substance metabolism, energy balance, intracellular homeostasis, and signal network integration | [53] |

| Ubiquitination | K, N-term | 8315 | Timing and homeostasis of plant growth and development, response to abiotic/biotic stresses, substance metabolism, energy balance, intracellular homeostasis, and signal network integration | [54] |

| SUMOylation | K | 139 | Response to abiotic/biotic stresses, timing and homeostasis of plant growth and development, maintain genome stability, substance metabolism, energy balance, intracellular homeostasis, and signal network integration | [55] |

| N-glycosylation | N, P, R | 3258 | Protein folding, plant growth and development, response to biotic stresses, substance metabolism, energy balance, intracellular homeostasis, and signal network integration | [56] |

| Methylation | R, K, C | 1299 | Epigenetic regulation | [57] |

| Acetylation | K, N-terminus | 23,042 | Epigenetic regulation | [34] |

| S-nitrosylation | C | 5924 | Response to abiotic/biotic stresses, plant growth and development | |

| Crotonylation | K | 15,404 | Photosynthesis, various substance metabolisms, and protein synthesis and quality control | [58] |

| 2-Hydroxyisobuturylation | K | 34,884 | Gene transcription, balance of substance metabolism, and response to biotic stresses | [59] |

| S-sulfenylation | C | 3871 | Cellular redox homeostasis | [60] |

| Reversible Cysteine Oxidation | C | 3826 | Cellular redox homeostasis | [61] |

| Succinylation | K | 2450 | Substance metabolism, energy balance, cellular homeostasis, and epigenetic regulation | [59] |

| S-Acylation | C, N-term | 1524 | Plant growth and development | [60] |

| Carbonylation | R, K, P, T, Y | 188 | Clearance of damaged proteins, and maintenance of cellular homeostasis | [62] |

| S-cyanylation | C | 132 | Cyanide metabolism and toxicity detoxification | [60] |

3. Post-Translational Modifications in Plant Abiotic Stress

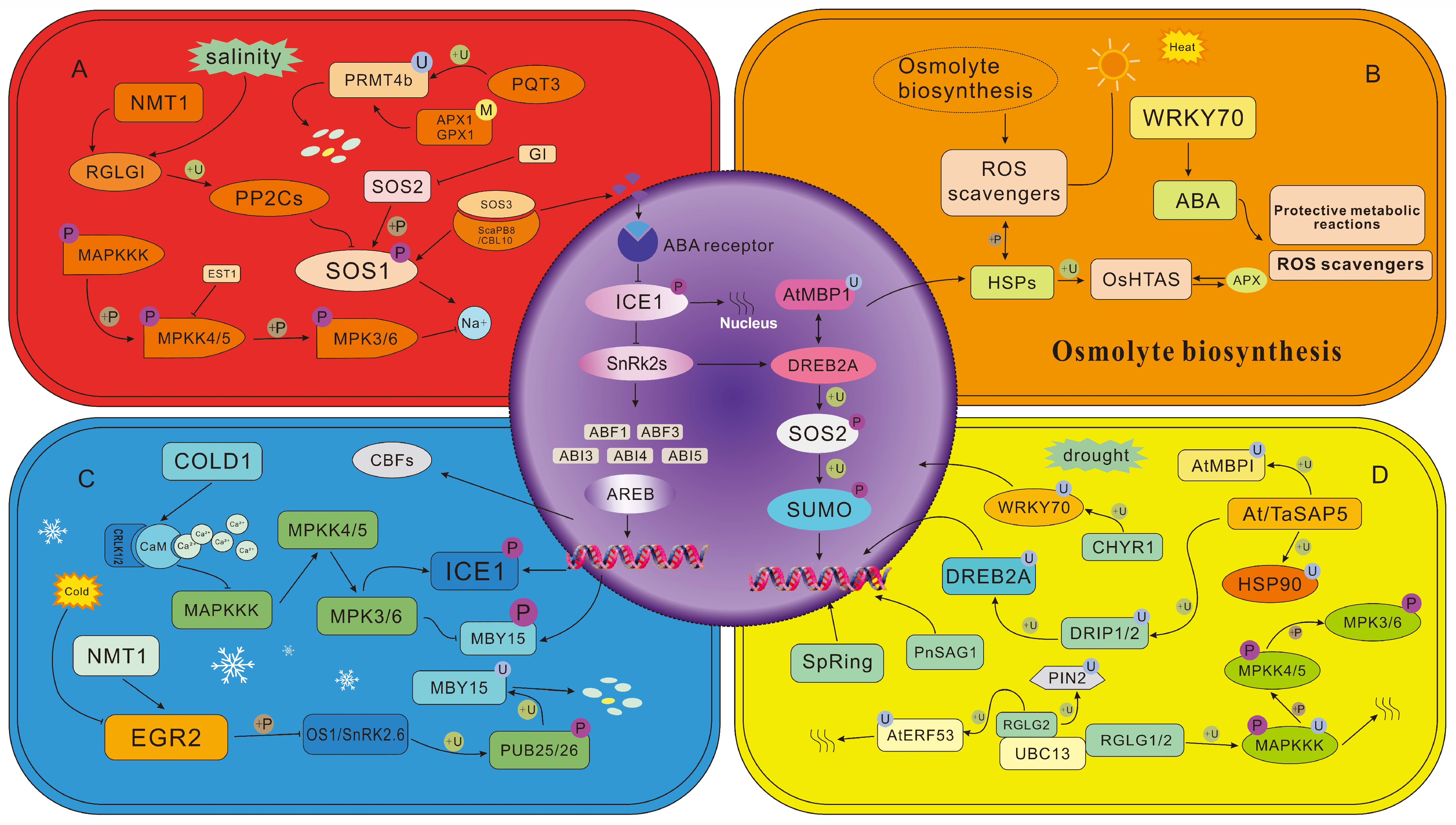

3.1. Heat Stress

3.2. Cold Stress

3.3. Drought Stress

3.4. Salt Stress

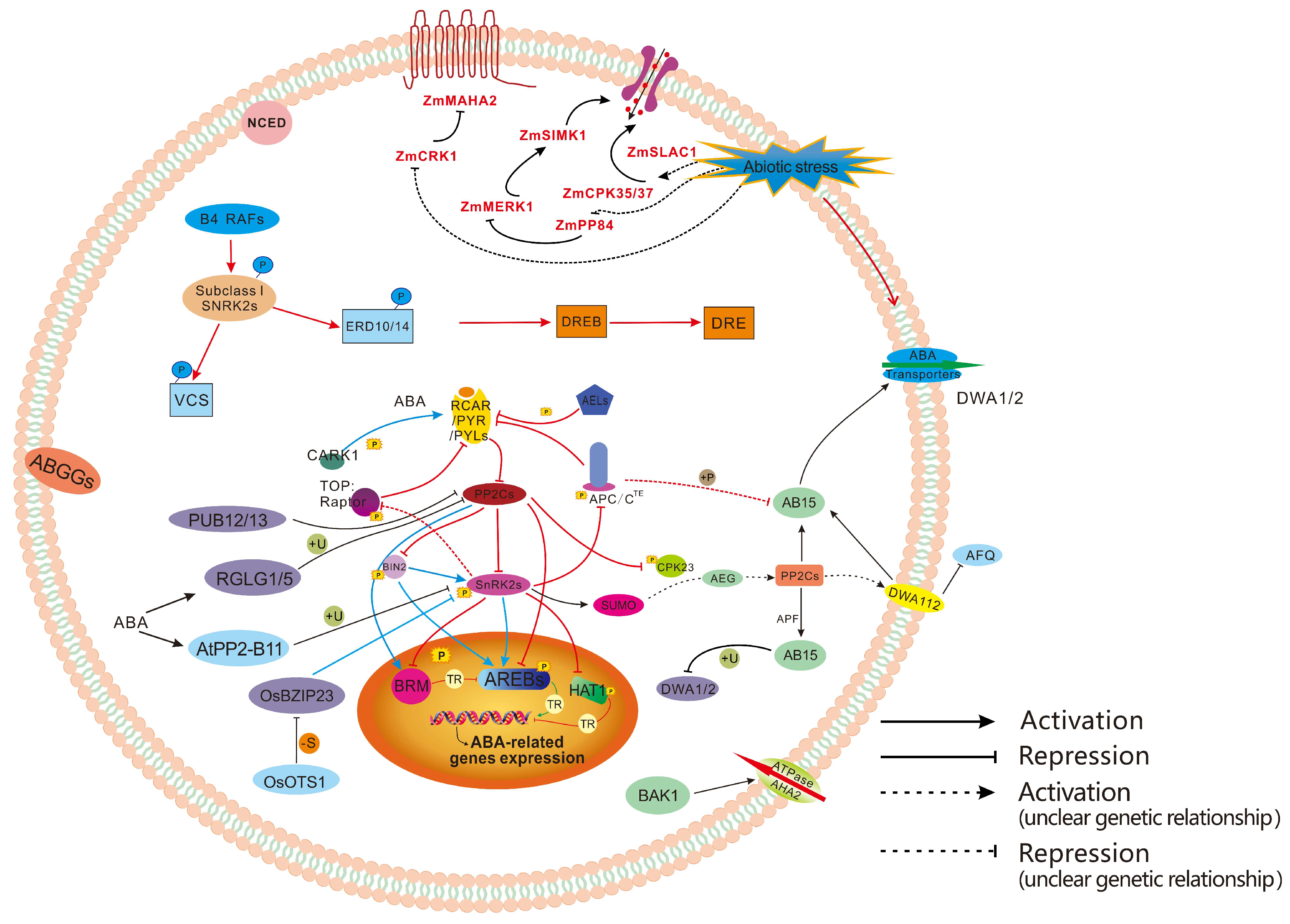

3.5. PTMs in ABA Signaling Transduction

4. PTM Crosstalk

4.1. Crosstalk Between Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination

4.2. Crosstalk Between Phosphorylation and SUMOylation

4.3. Crosstalk Between Ubiquitination and SUMOylation

4.4. Crosstalk Between Phosphorylation, Ubiquitination, and SUMOylation

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millar, A.H.; Heazlewood, J.L.; Giglione, C.; Holdsworth, M.J.; Bachmair, A.; Schulze, W.X. The Scope, Functions, and Dynamics of Posttranslational Protein Modifications. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 119–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Xian, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Protein post-translational modifications (PTM(S)) unlocking resilience to abiotic stress in horticultural crops: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A.; Alsberg, C.L. The Cleavage Products of Vitellin. J. Biol. Chem. 1906, 2, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, J. Protein Phosphorylation in Plant Cell Signaling. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2358, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergner, J.; Frejno, M.; List, M.; Papacek, M.; Chen, X.; Chaudhary, A.; Samaras, P.; Richter, S.; Shikata, H.; Messerer, M.; et al. Mass-spectrometry-based draft of the Arabidopsis proteome. Nature 2020, 579, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, N.M.; Nolan, T.M.; Wang, P.; Song, G.; Montes, C.; Valentine, C.T.; Guo, H.; Sozzani, R.; Yin, Y.; Walley, J.W. Integrated omics networks reveal the temporal signaling events of brassinosteroid response in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Park, C.H.; Hsu, C.C.; Kim, Y.W.; Ko, Y.W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.Y.; Hsiao, Y.C.; Branon, T.; Kaasik, K.; et al. Mapping the signaling network of BIN2 kinase using TurboID-mediated biotin labeling and phosphoproteomics. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montes, C.; Wang, P.; Liao, C.Y.; Nolan, T.M.; Song, G.; Clark, N.M.; Elmore, J.M.; Guo, H.; Bassham, D.C.; Yin, Y.; et al. Integration of multi-omics data reveals interplay between brassinosteroid and Target of Rapamycin Complex signaling in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, S. MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2013, 51, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S. Conveying endogenous and exogenous signals: MAPK cascades in plant growth and defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, K.D. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination: Targeting of proteins for degradation by the proteasome. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000, 11, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isono, E.; Nagel, M.K. Deubiquitylating enzymes and their emerging role in plant biology. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J.; Sun, L.J. Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Mol. Cell 2009, 33, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komander, D.; Rape, M. The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meusser, B.; Hirsch, C.; Jarosch, E.; Sommer, T. ERAD: The long road to destruction. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005, 7, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, L.; Zhao, H. Characterization of the Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme Gene Family in Rice and Evaluation of Expression Profiles under Abiotic Stresses and Hormone Treatments. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; You, X.; Zhang, C.; Fang, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, F.; Kang, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. An ORFeome of rice E3 ubiquitin ligases for global analysis of the ubiquitination interactome. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurepa, J.; Walker, J.M.; Smalle, J.; Gosink, M.M.; Davis, S.J.; Durham, T.L.; Sung, D.Y.; Vierstra, R.D. The small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein modification system in Arabidopsis. Accumulation of SUMO1 and -2 conjugates is increased by stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 6862–6872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.C.; Choi, W.; Park, H.J.; Cheong, M.S.; Koo, Y.D.; Shin, G.; Chung, W.S.; Kim, W.Y.; Kim, M.G.; Bressan, R.A.; et al. Identification and molecular properties of SUMO-binding proteins in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells 2011, 32, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Lee, K.J. Post-translational modifications and their biological functions: Proteomic analysis and systematic approaches. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 37, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qian, K. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: Emerging mechanisms and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitling, J.; Aebi, M. N-linked protein glycosylation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a013359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, M.; Kinoshita, T. GPI-anchor remodeling: Potential functions of GPI-anchors in intracellular trafficking and membrane dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2012, 1821, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Talbot, N.J.; Chen, X.L. Protein glycosylation during infection by plant pathogenic fungi. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanier, G.; Lucas, P.L.; Loutelier-Bourhis, C.; Vanier, J.; Plasson, C.; Walet-Balieu, M.L.; Tchi-Song, P.C.; Remy-Jouet, I.; Richard, V.; Bernard, S.; et al. Heterologous expression of the N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I dictates a reinvestigation of the N-glycosylation pathway in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y. Quantification of N-glycosylation site occupancy status based on labeling/label-free strategies with LC-MS/MS. Talanta 2017, 170, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.P.; Javed, A.; Hard, E.R.; Pratt, M.R. Methods for Studying Site-Specific O-GlcNAc Modifications: Successes, Limitations, and Important Future Goals. JACS Au 2022, 2, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murn, J.; Shi, Y. The winding path of protein methylation research: Milestones and new frontiers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bedford, M.T. Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.W.; Cho, Y.; Bae, G.U.; Kim, S.N.; Kim, Y.K. Protein arginine methyltransferases: Promising targets for cancer therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewary, S.K.; Zheng, Y.G.; Ho, M.C. Protein arginine methyltransferases: Insights into the enzyme structure and mechanism at the atomic level. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 2917–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, H.; Shi, X. Lysine methylation: Beyond histones. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2012, 44, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, A.C.; Hartl, M.; Boersema, P.J.; Mann, M.; Finkemeier, I. The mitochondrial lysine acetylome of Arabidopsis. Mitochondrion 2014, 19 Pt B, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, S.; Yu, C.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Wu, K. Histone Acetylation and Plant Development. Enzymes 2016, 40, 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.M.; To, T.K.; Ishida, J.; Morosawa, T.; Kawashima, M.; Matsui, A.; Toyoda, T.; Kimura, H.; Shinozaki, K.; Seki, M. Alterations of lysine modifications on the histone H3 N-tail under drought stress conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.J.; Tian, L. Roles of dynamic and reversible histone acetylation in plant development and polyploidy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Struct. Expr. 2007, 1769, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambi, S.; Gupta, K.; Bhattacharyya, M.; Ramakrishnan, P.; Ravikumar, V.; Siddiqui, N.; Thomas, A.T.; Visweswariah, S.S. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein lysine acylation in mycobacteria regulates fatty acid and propionate metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 14114–14124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Xiong, H.; Lin, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, H.; Xie, L.; Zhao, W.; Yao, Y.; et al. Acetylation of metabolic enzymes coordinates carbon source utilization and metabolic flux. Science 2010, 327, 1004–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Malhotra, A.; Deutscher, M.P. Acetylation regulates the stability of a bacterial protein: Growth stage-dependent modification of RNase R. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scroggins, B.T.; Robzyk, K.; Wang, D.; Marcu, M.G.; Tsutsumi, S.; Beebe, K.; Cotter, R.J.; Felts, S.; Toft, D.; Karnitz, L.; et al. An acetylation site in the middle domain of Hsp90 regulates chaperone function. Mol. Cell 2007, 25, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Finkemeier, I.; Guan, W.; Tossounian, M.A.; Wei, B.; Young, D.; Huang, J.; Messens, J.; Yang, X.; Zhu, J.; et al. Oxidative stress-triggered interactions between the succinyl- and acetyl-proteomes of rice leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lv, Y.; Mujahid, H.; Edelmann, M.J.; Zhao, H.; Peng, X.; Peng, Z. Proteome-wide lysine acetylation identification in developing rice (Oryza sativa) seeds and protein co-modification by acetylation, succinylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2018, 1866, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Gai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, K.; Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Ding, Z. Comprehensive proteome analyses of lysine acetylation in tea leaves by sensing nitrogen nutrition. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Chen, L.; Zuo, J. Protein S-Nitrosylation in plants: Current progresses and challenges. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019, 61, 1206–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, X.; Wei, S.; Liu, Y. The roles of protein S-nitrosylation in regulating the growth and development of plants: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Fang, H.; Huang, D.; Pan, X.; Liao, W. Role of protein S-nitrosylation in plant growth and development. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.; Mioto, P.T.; Palma, J.M.; Corpas, F.J. Detection of Protein S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) in Plant Samples on Diaminofluorescein (DAF) Gels. Bio-Protocol 2017, 7, e2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamotte, O.; Bertoldo, J.B.; Besson-Bard, A.; Rosnoblet, C.; Aimé, S.; Hichami, S.; Terenzi, H.; Wendehenne, D. Protein S-nitrosylation: Specificity and identification strategies in plants. Front. Chem. 2014, 2, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astier, J.; Rasul, S.; Koen, E.; Manzoor, H.; Besson-Bard, A.; Lamotte, O.; Jeandroz, S.; Durner, J.; Lindermayr, C.; Wendehenne, D. S-nitrosylation: An emerging post-translational protein modification in plants. Plant Sci. 2011, 181, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, D.T.; Matsumoto, A.; Kim, S.O.; Marshall, H.E.; Stamler, J.S. Protein S-nitrosylation: Purview and parameters. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Luo, H.; Lee, S.; Jin, F.; Yang, J.S.; Montellier, E.; Buchou, T.; Cheng, Z.; Rousseaux, S.; Rajagopal, N.; et al. Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell 2011, 146, 1016–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xue, C.; Fang, Y.; Chen, G.; Peng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, G.; Gu, M.; Wang, K.; et al. Global Involvement of Lysine Crotonylation in Protein Modification and Transcription Regulation in Rice. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2018, 17, 1922–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.H.; Xu, T. Protein phosphorylation: A molecular switch in plant signaling. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, D.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Pan, R. Protein ubiquitination in plant peroxisomes. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Lai, J.; Yang, C. SUMOylation: A critical transcription modulator in plant cells. Plant Sci. 2021, 310, 110987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Du, Y.; Fu, M.; Jiao, W. N-Glycosylation-The Behind-the-Scenes ‘Manipulative Hand’ of Plant Pathogen Invasiveness. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 26, e70123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, G. The mechanism of histone lysine methylation of plant involved in gene expression and regulation. Yi Chuan 2014, 36, 208–219. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-de la Rosa, P.A.; Aragón-Rodríguez, C.; Ceja-López, J.A.; García-Arteaga, K.F.; De-la-Peña, C. Lysine crotonylation: A challenging new player in the epigenetic regulation of plants. J. Proteom. 2022, 255, 104488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, S.; Tian, H.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Chen, D.; Zhao, S.; Yan, X.; Niaz, M.; et al. Functions of lysine 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation and future perspectives on plants. Proteomics 2023, 23, e2300045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpas, F.J.; González-Gordo, S.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.; Muñoz-Vargas, M.A.; Palma, J.M. Thiol-based Oxidative Posttranslational Modifications (OxiPTMs) of Plant Proteins. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022, 63, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosse, M.; Rehders, T.; Eirich, J.; Finkemeier, I.; Selinski, J. Cysteine oxidation as a regulatory mechanism of Arabidopsis plastidial NAD-dependent malate dehydrogenase. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciacka, K.; Tymiński, M.; Gniazdowska, A.; Krasuska, U. Carbonylation of proteins-an element of plant ageing. Planta 2020, 252, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Mei, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, L. Differential proteomic analysis reveals sequential heat stress-responsive regulatory network in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) taproot. Planta 2018, 247, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, F.; Shao, Y.; He, J. Regulatory Mechanisms of Heat Stress Response and Thermomorphogenesis in Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Z.; Zhou, M.; Ding, Y.F.; Zhu, C. Gene Networks Involved in Plant Heat Stress Response and Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guihur, A.; Rebeaud, M.E.; Goloubinoff, P. How do plants feel the heat and survive? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022, 47, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorger, P.K.; Pelham, H.R. Yeast heat shock factor is an essential DNA-binding protein that exhibits temperature-dependent phosphorylation. Cell 1988, 54, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.C.; Liao, H.T.; Charng, Y.Y. The role of class A1 heat shock factors (HSFA1s) in response to heat and other stresses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, F.; Larkindale, J.; Kiehlmann, E.; Ganguli, A.; Englich, G.; Vierling, E.; von Koskull-Döring, P. A cascade of transcription factor DREB2A and heat stress transcription factor HsfA3 regulates the heat stress response of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008, 53, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charng, Y.Y.; Liu, H.C.; Liu, N.Y.; Chi, W.T.; Wang, C.N.; Chang, S.H.; Wang, T.T. A heat-inducible transcription factor, HsfA2, is required for extension of acquired thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Gao, K.; Ren, H.; Tang, W. Molecular mechanisms governing plant responses to high temperatures. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurop, M.K.; Huyen, C.M.; Kelly, J.H.; Blagg, B.S.J. The heat shock response and small molecule regulators. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 226, 113846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.T.; Li, G.L.; Chang, H.; Sun, D.Y.; Zhou, R.G.; Li, B. Calmodulin-binding protein phosphatase PP7 is involved in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl, A.; Schöffl, F.; Schell, J.; Koncz, C.; Bakó, L. Phosphorylation by a cyclin-dependent kinase modulates DNA binding of the Arabidopsis heat-shock transcription factor HSF1 in vitro. Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Lv, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Meng, Q. SUMO E3 Ligase SlSIZ1 Facilitates Heat Tolerance in Tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohama, N.; Kusakabe, K.; Mizoi, J.; Zhao, H.; Kidokoro, S.; Koizumi, S.; Takahashi, F.; Ishida, T.; Yanagisawa, S.; Shinozaki, K.; et al. The Transcriptional Cascade in the Heat Stress Response of Arabidopsis Is Strictly Regulated at the Level of Transcription Factor Expression. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, A.; Bublak, D.; Schleiff, E.; Scharf, K.D. Crosstalk between Hsp90 and Hsp70 chaperones and heat stress transcription factors in tomato. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Peer, R.; Schuster, S.; Meiri, D.; Breiman, A.; Avni, A. Sumoylation of Arabidopsis heat shock factor A2 (HsfA2) modifies its activity during acquired thermotholerance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 74, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Rogers, R.; Matunis, M.J.; Mayhew, C.N.; Goodson, M.L.; Park-Sarge, O.K.; Sarge, K.D. Regulation of heat shock transcription factor 1 by stress-induced SUMO-1 modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 40263–40267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Han, D.; Wu, Y.; Ye, W.; Yang, H.; Li, G.; Cui, F.; Wan, S.; et al. SUMOylation Stabilizes the Transcription Factor DREB2A to Improve Plant Thermotolerance. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Hwang, J.E.; Lim, C.J.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Lim, C.O. Arabidopsis DREB2C functions as a transcriptional activator of HsfA3 during the heat stress response. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 401, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, D.; Chong, K. Cold signaling in plants: Insights into mechanisms and regulation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, W.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, D.; Pan, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; et al. COLD1 confers chilling tolerance in rice. Cell 2015, 160, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yang, S. Molecular Regulation of CBF Signaling in Cold Acclimation. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Memon, A.G.; Ahmad, A.; Iqbal, M.S. Calcium Mediated Cold Acclimation in Plants: Underlying Signaling and Molecular Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 855559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, G.E.; Johnson, J.P., Jr.; Zagotta, W.N. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: Shedding light on the opening of a channel pore. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, Z.; Cheng, J.; Hu, P.; Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Jin, M.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; et al. CYCLIC NUCLEOTIDE-GATED ION CHANNELs 14 and 16 Promote Tolerance to Heat and Chilling in Rice. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 1794–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Li, L.; Peng, D.; Liu, M.; Wei, A.; Li, X. TaFDL2-1A interacts with TabZIP8-7A protein to cope with drought stress via the abscisic acid signaling pathway. Plant Sci. 2021, 311, 111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, T.; Otomi, Y.; Nakajima, Y.; Soga, K.; Wakabayashi, K.; Iida, H.; Hoson, T. MCA1 and MCA2 Are Involved in the Response to Hypergravity in Arabidopsis Hypocotyls. Plants 2020, 9, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-García, M.; González-Córdova, C.D.; Ponce-Pineda, I.G.; Cano-Ramírez, D.; Romero-Colín, F.M.; Arroyo-Pérez, E.E.; King-Díaz, B.; Zavafer, A.; Gavilanes-Ruíz, M. Effects of MPK3 and MPK6 kinases on the chloroplast architecture and function induced by cold acclimation in Arabidopsis. Photosynth. Res. 2021, 149, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, P.; Si, T.; Hsu, C.C.; Wang, L.; Zayed, O.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, J.; Tao, W.A.; et al. MAP Kinase Cascades Regulate the Cold Response by Modulating ICE1 Protein Stability. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 618–629.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jia, Y.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Gong, Z.; Yang, S. Plasma Membrane CRPK1-Mediated Phosphorylation of 14-3-3 Proteins Induces Their Nuclear Import to Fine-Tune CBF Signaling during Cold Response. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 117–128.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Z.; Yang, S. MPK3- and MPK6-Mediated ICE1 Phosphorylation Negatively Regulates ICE1 Stability and Freezing Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 630–642.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Lv, J.; Shi, Y.; Gao, J.; Hua, J.; Song, C.; Gong, Z.; Yang, S. EGR2 phosphatase regulates OST1 kinase activity and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e99819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Z.; Zhu, J. OST1 phosphorylates ICE1 to enhance plant cold tolerance. Sci. China Life Sci. 2015, 58, 317–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margalha, L.; Elias, A.; Belda-Palazón, B.; Peixoto, B.; Confraria, A.; Baena-González, E. HOS1 promotes plant tolerance to low-energy stress via the SnRK1 protein kinase. Plant J. 2023, 115, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, K.; Li, H.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Song, C.; Gong, Z.; Yang, S. BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE2 Negatively Regulates the Stability of Transcription Factor ICE1 in Response to Cold Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 2682–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Shi, H.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, H.; Yang, S.; Zheng, W.; et al. Natural variation in CTB4a enhances rice adaptation to cold habitats. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, R.; Wu, B.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, G. OsWRKY70 Plays Opposite Roles in Blast Resistance and Cold Stress Tolerance in Rice. Rice 2024, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Zheng, L.; Wu, J.; Duan, M.; Liu, Q.; Liu, P.; Shen, C.; Liu, J.; Ye, Q.; Wen, J.; et al. The thioesterase APT1 is a bidirectional-adjustment redox sensor. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Zheng, L.; Liu, P.; Liu, Q.; Ji, T.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Liu, L.; Dong, J.; Wang, T. The S-acylation cycle of transcription factor MtNAC80 influences cold stress responses in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 2629–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, G.; Huang, S.; Wu, X.; Hu, L.; Yu, J. The S-nitrosylation of monodehydroascorbate reductase positively regulated the low temperature tolerance of mini Chinese cabbage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Dwivedi, S.; Bhagavatula, L.; Datta, S. Integration of light and ABA signaling pathways to combat drought stress in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.K.; Dubeaux, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Schroeder, J.I. Signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid-mediated stomatal closure. Plant J. 2021, 105, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Guo, Y.; Gong, Z. Protein kinases in plant responses to drought, salt, and cold stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Niu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. Signaling Transduction of ABA, ROS, and Ca(2+) in Plant Stomatal Closure in Response to Drought. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Liu, X.D.; Waseem, M.; Guang-Qian, Y.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Jahan, M.S.; Fang, X.W. ABA activated SnRK2 kinases: An emerging role in plant growth and physiology. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2071024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, B.; Brodsky, D.E.; Xue, S.; Negi, J.; Iba, K.; Kangasjärvi, J.; Ghassemian, M.; Stephan, A.B.; Hu, H.; Schroeder, J.I. Reconstitution of abscisic acid activation of SLAC1 anion channel by CPK6 and OST1 kinases and branched ABI1 PP2C phosphatase action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 10593–10598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Sato, Y.; Fukao, Y.; Fujiwara, M.; Umezawa, T.; Shinozaki, K.; Hibi, T.; Taniguchi, M.; Miyake, H.; Goto, D.B.; et al. Threonine at position 306 of the KAT1 potassium channel is essential for channel activity and is a target site for ABA-activated SnRK2/OST1/SnRK2.6 protein kinase. Biochem. J. 2009, 424, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Fujita, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Mogami, J.; Todaka, D.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Four Arabidopsis AREB/ABF transcription factors function predominantly in gene expression downstream of SnRK2 kinases in abscisic acid signalling in response to osmotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Pivotal role of the AREB/ABF-SnRK2 pathway in ABRE-mediated transcription in response to osmotic stress in plants. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 147, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-mediated transcriptional regulation in response to osmotic stress in plants. J. Plant Res. 2011, 124, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, F.; Takahashi, F.; Kidokoro, S.; Kameoka, H.; Suzuki, T.; Uga, Y.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Constitutively active B2 Raf-like kinases are required for drought-responsive gene expression upstream of ABA-activated SnRK2 kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2221863120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzio, G.A.; Rodriguez, P.L. Dual regulation of SnRK2 signaling by Raf-like MAPKKKs. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1260–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; Mu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Xie, S.; et al. Initiation and amplification of SnRK2 activation in abscisic acid signaling. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Inoue, T.; Hiraide, M.; Khatun, N.; Jahan, A.; Kuwata, K.; Katagiri, S.; Umezawa, T.; Yotsui, I.; Sakata, Y.; et al. Activation of SnRK2 by Raf-like kinase ARK represents a primary mechanism of ABA and abiotic stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Hsu, C.C.; Du, Y.; Sang, T.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Satheesh, V.; et al. A RAF-SnRK2 kinase cascade mediates early osmotic stress signaling in higher plants. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuta, S.; Masuda, G.; Bak, H.; Shinozawa, A.; Kamiyama, Y.; Umezawa, T.; Takezawa, D.; Yotsui, I.; Taji, T.; Sakata, Y. Arabidopsis Raf-like kinases act as positive regulators of subclass III SnRK2 in osmostress signaling. Plant J. 2020, 103, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fàbregas, N.; Yoshida, T.; Fernie, A.R. Role of Raf-like kinases in SnRK2 activation and osmotic stress response in plants. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Feng, Z.; Ding, Y.; Qi, Y.; Jiang, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qi, J.; Song, C.; Yang, S.; et al. RAF22, ABI1 and OST1 form a dynamic interactive network that optimizes plant growth and responses to drought stress in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1192–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Jing, B.; Lin, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J.; Hu, Z. Phosphorylation of sugar transporter TST2 by protein kinase CPK27 enhances drought tolerance in tomato. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 1005–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, W.; Yang, J.; Fu, J.; Xiong, L. Synergistic regulation of drought-responsive genes by transcription factor OsbZIP23 and histone modification in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Wu, T.; Ma, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Bian, M.; Bai, H.; Jiang, W.; Du, X. Rice Transcription Factor OsWRKY55 Is Involved in the Drought Response and Regulation of Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gavya, S.L.; Zhou, Z.; Urano, D.; Lau, O.S. Abscisic acid regulates stomatal production by imprinting a SnRK2 kinase-mediated phosphocode on the master regulator SPEECHLESS. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eadd2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosa-Puente, B.; Leftley, N.; von Wangenheim, D.; Banda, J.; Srivastava, A.K.; Hill, K.; Truskina, J.; Bhosale, R.; Morris, E.; Srivastava, M.; et al. Root branching toward water involves posttranslational modification of transcription factor ARF7. Science 2018, 362, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uga, Y.; Sugimoto, K.; Ogawa, S.; Rane, J.; Ishitani, M.; Hara, N.; Kitomi, Y.; Inukai, Y.; Ono, K.; Kanno, N.; et al. Control of root system architecture by DEEPER ROOTING 1 increases rice yield under drought conditions. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, B.; Zhou, Y.; He, S.J.; Tang, S.Y.; Lu, X.; Xie, Q.; Chen, S.Y.; Zhang, J.S. E3 ubiquitin ligase SOR1 regulates ethylene response in rice root by modulating stability of Aux/IAA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4513–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, S.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Peng, K.; Geng, W.; Xia, S.; Liu, Q.; et al. IbNIEL-mediated degradation of IbNAC087 regulates jasmonic acid-dependent salt and drought tolerance in sweet potato. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Ma, C.N.; Gu, K.D.; Wang, J.H.; Yu, J.Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; He, J.X.; Hu, D.G.; Sun, Q. The BTB-BACK-TAZ domain protein MdBT2 reduces drought resistance by weakening the positive regulatory effect of MdHDZ27 on apple drought tolerance via ubiquitination. Plant J. 2024, 119, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, X.; Qiu, L.; Mei, Q.; Li, N.; Ma, F. MdbHLH160 is stabilized via reduced MdBT2-mediated degradation to promote MdSOD1 and MdDREB2A-like expression for apple drought tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 1181–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J. Genet. Genom. 2024, 51, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Du, W.; Yang, Y.; Schumaker, K.S.; Guo, Y. A calcium-independent activation of the Arabidopsis SOS2-like protein kinase24 by its interacting SOS3-like calcium binding protein1. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 2197–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shen, L.; Han, X.; He, G.; Fan, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jin, W.; et al. Phosphatidic acid-regulated SOS2 controls sodium and potassium homeostasis in Arabidopsis under salt stress. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e112401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Lin, H.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fuglsang, A.T.; Palmgren, M.G.; Wu, W.; Guo, Y. Phosphorylation of SOS3-like calcium-binding proteins by their interacting SOS2-like protein kinases is a common regulatory mechanism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 2235–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lin, H.; Chen, S.; Becker, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Kudla, J.; Schumaker, K.S.; Guo, Y. Inhibition of the Arabidopsis salt overly sensitive pathway by 14-3-3 proteins. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1166–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, Q.; Guo, Y. SALT OVERLY SENSITIVE 1 is inhibited by clade D Protein phosphatase 2C D6 and D7 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Halfter, U.; Ishitani, M.; Zhu, J.K. Molecular characterization of functional domains in the protein kinase SOS2 that is required for plant salt tolerance. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 1383–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ni, X.; Wang, Q.; Jia, Y.; Xu, X.; Wu, H.; Fu, P.; Wen, H.; Guo, Y.; et al. Structural basis for the activity regulation of Salt Overly Sensitive 1 in Arabidopsis salt tolerance. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1915–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Nie, J.; Cao, C.; Jin, Y.; Yan, M.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, W. Phosphatidic acid mediates salt stress response by regulation of MPK6 in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2010, 188, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, S.; Dong, D.; Zhou, R.; Wang, H. Arabidopsis Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes UBC7, UBC13, and UBC14 Are Required in Plant Responses to Multiple Stress Conditions. Plants 2020, 9, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Nie, N.; Sun, S.; Hu, Y.; Bai, Y.; He, S.; Zhao, N.; Liu, Q.; Zhai, H. A novel sweetpotato RING-H2 type E3 ubiquitin ligase gene IbATL38 enhances salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2021, 304, 110802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Lu, D.; Liu, X. The Arabidopsis ubiquitin ligases ATL31 and ATL6 regulate plant response to salt stress in an ABA-independent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 685, 149156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jang, C.S. E3 ligase, the Oryza sativa salt-induced RING finger protein 4 (OsSIRP4), negatively regulates salt stress responses via degradation of the OsPEX11-1 protein. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 105, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.X.; Li, S.S.; Yue, Q.Y.; Li, H.L.; Lu, J.; Li, W.C.; Wang, Y.N.; Liu, J.X.; Guo, X.L.; Wu, X.; et al. MdHMGB15-MdXERICO-MdNRP module mediates salt tolerance of apple by regulating the expression of salt stress-related genes. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 79, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhao, B.; Wu, S.; Jia, B.; Sun, X.; Zhang, D.; Sun, M. Soybean RING-type E3 ligase GmCHYR16 ubiquitinates the GmERF71 transcription factor for degradation to negatively regulate bicarbonate stress tolerance. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 1128–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Li, S.; Liesche, J. UBIQUITIN-CONJUGATING ENZYME34 mediates pyrophosphatase AVP1 turnover and regulates abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiaf015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Cao, B.; Wei, J.W.; Gong, B. Redesigning a S-nitrosylated pyruvate-dependent GABA transaminase 1 to generate high-malate and saline-alkali-tolerant tomato. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 2148–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.W.; Liu, M.; Zhao, D.; Du, P.; Yan, L.; Liu, D.; Shi, Q.; Yang, C.; Qin, G.; Gong, B. Melatonin confers saline-alkali tolerance in tomato by alleviating nitrosative damage and S-nitrosylation of H+-ATPase 2. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wei, J.W.; Shan, Q.; Liu, M.; Xu, J.; Gong, B. Genetic engineering of drought- and salt-tolerant tomato via Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase S-nitrosylation. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 1038–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Hou, X.; Feng, L.; Liu, Y.; Kong, Y.; Cui, A.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, D.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; et al. SERK3A and SERK3B could be S-nitrosylated and enhance the salt resistance in tomato seedlings. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 133084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Kang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Hu, S.; Zhu, C.; Li, T.; Li, G.; Hu, X. The RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase SlMIEL1 interacts with SlNAC35 to regulate JA biosynthesis and mediate saline-alkali stress responses in tomato. Plant J. 2025, 124, e70598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Liu, T.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Cui, Y.; Lu, S.; Gong, X.; Mao, K.; et al. MdSINA2-MdNAC104 Module Regulates Apple Alkaline Resistance by Affecting γ-Aminobutyric Acid Synthesis and Transport. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2400930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhi, W.; Qiao, H.; Huang, J.; Li, S.; Lu, Q.; Wang, N.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, J.; et al. H2O2-dependent oxidation of the transcription factor GmNTL1 promotes salt tolerance in soybean. Plant Cell 2023, 36, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, K.; Upadhyay, N.; Kumar, N.; Yadav, G.; Singh, J.; Mishra, R.K.; Kumar, V.; Verma, R.; Upadhyay, R.G.; Pandey, M.; et al. Abscisic Acid Signaling and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants: A Review on Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Park, Y.; Hwang, I. Abscisic acid: Biosynthesis, inactivation, homoeostasis and signalling. Essays Biochem. 2015, 58, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Hsu, C.C.; Liu, X.; Fu, L.; Hou, Y.J.; Du, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhang, C.; et al. Reciprocal Regulation of the TOR Kinase and ABA Receptor Balances Plant Growth and Stress Response. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 100–112.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberger, C.L.; Chen, J. To Grow or Not to Grow: TOR and SnRK2 Coordinate Growth and Stress Response in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.H.; Qu, L.; Xu, Z.H.; Zhu, J.K.; Xue, H.W. EL1-like Casein Kinases Suppress ABA Signaling and Responses by Phosphorylating and Destabilizing the ABA Receptors PYR/PYLs in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. CARK1 mediates ABA signaling by phosphorylation of ABA receptors. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.M.; Soon, F.F.; Zhou, X.E.; West, G.M.; Kovach, A.; Suino-Powell, K.M.; Chalmers, M.J.; Li, J.; Yong, E.L.; Zhu, J.K.; et al. Structural basis for basal activity and autoactivation of abscisic acid (ABA) signaling SnRK2 kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 21259–21264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Dai, C.; Lee, M.M.; Kwak, J.M.; Nam, K.H. BRI1-Associated Receptor Kinase 1 Regulates Guard Cell ABA Signaling Mediated by Open Stomata 1 in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilela, B.; Nájar, E.; Lumbreras, V.; Leung, J.; Pagès, M. Casein Kinase 2 Negatively Regulates Abscisic Acid-Activated SnRK2s in the Core Abscisic Acid-Signaling Module. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Hou, C.; Ren, Z.; Pan, Y.; Jia, J.; Zhang, H.; Bai, F.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, H.; He, Y.; et al. A molecular pathway for CO2 response in Arabidopsis guard cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Pan, S.; Dong, R.; Tang, G.; Barajas-Lopez Jde, D.; et al. GSK3-like kinases positively modulate abscisic acid signaling through phosphorylating subgroup III SnRK2s in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9651–9656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, G.; Zhang, H. TAP46 plays a positive role in the ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Z.; Wang, X. Abscisic Acid Signaling Inhibits Brassinosteroid Signaling through Dampening the Dephosphorylation of BIN2 by ABI1 and ABI2. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulekar, J.J.; Huq, E. Expanding roles of protein kinase CK2 in regulating plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 2883–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, S.; Batelli, G.; Wang, B.; Duan, C.G.; Wang, X.; Xing, L.; et al. Type One Protein Phosphatase 1 and Its Regulatory Protein Inhibitor 2 Negatively Regulate ABA Signaling. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.J.; Chen, K.; Sun, S.; Zhao, Y. Osmotic signaling releases PP2C-mediated inhibition of Arabidopsis SnRK2s via the receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase BIK1. EMBO J. 2024, 43, 6076–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, N.; Min, M.K.; Choi, E.H.; Kim, N.; Moon, S.J.; Yoon, I.; Kwon, T.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, B.G. The protein phosphatase 2C clade A protein OsPP2C51 positively regulates seed germination by directly inactivating OsbZIP10. Plant Mol. Biol. 2017, 93, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, W.; Tang, N.; Yang, J.; Peng, L.; Ma, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Xiong, L. Feedback Regulation of ABA Signaling and Biosynthesis by a bZIP Transcription Factor Targets Drought-Resistance-Related Genes. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2810–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Guo, C.; Peng, J.; Li, C.; Wan, F.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, Y.; Qi, L.; Sun, K.; et al. ABRE-BINDING FACTORS play a role in the feedback regulation of ABA signaling by mediating rapid ABA induction of ABA co-receptor genes. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, T.; Yin, Y.; Lin, H. Transcription factor HAT1 is a substrate of SnRK2.3 kinase and negatively regulates ABA synthesis and signaling in Arabidopsis responding to drought. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pei, Y.; Zhu, F.; He, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, B.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Khan, A.; Jahangir, M.; et al. CaSnRK2.4-mediated phosphorylation of CaNAC035 regulates abscisic acid synthesis in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) responding to cold stress. Plant J. 2024, 117, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, D.; Scherzer, S.; Mumm, P.; Stange, A.; Marten, I.; Bauer, H.; Ache, P.; Matschi, S.; Liese, A.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.; et al. Activity of guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is controlled by drought-stress signaling kinase-phosphatase pair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21425–21430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Ebisu, Y.; Shimazaki, K.I. Reconstitution of Abscisic Acid Signaling from the Receptor to DNA via bHLH Transcription Factors. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, D.; Scherzer, S.; Mumm, P.; Marten, I.; Ache, P.; Matschi, S.; Liese, A.; Wellmann, C.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.; Grill, E.; et al. Guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is regulated by CDPK protein kinases with distinct Ca2+ affinities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8023–8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, D.; Wang, C.; He, J.; Liao, H.; Duan, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gong, Z. A plasma membrane receptor kinase, GHR1, mediates abscisic acid- and hydrogen peroxide-regulated stomatal movement in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2546–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Gao, Y.Q.; Wu, W.H.; Chen, L.M.; Wang, Y. Two calcium-dependent protein kinases enhance maize drought tolerance by activating anion channel ZmSLAC1 in guard cells. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.D.; Jia, D.; Qi, L.; Jing, R.; Hao, J.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Chen, L.M. ZmCRK1 negatively regulates maize’s response to drought stress by phosphorylating plasma membrane H(+)-ATPase ZmMHA2. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 1362–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hõrak, H.; Sierla, M.; Tõldsepp, K.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.S.; Nuhkat, M.; Valk, E.; Pechter, P.; Merilo, E.; Salojärvi, J.; et al. A Dominant Mutation in the HT1 Kinase Uncovers Roles of MAP Kinases and GHR1 in CO2-Induced Stomatal Closure. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 2493–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueso, E.; Rodriguez, L.; Lorenzo-Orts, L.; Gonzalez-Guzman, M.; Sayas, E.; Muñoz-Bertomeu, J.; Ibañez, C.; Serrano, R.; Rodriguez, P.L. The single-subunit RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase RSL1 targets PYL4 and PYR1 ABA receptors in plasma membrane to modulate abscisic acid signaling. Plant J. 2014, 80, 1057–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Lou, L.; Tian, M.; Li, Q.; Ding, Y.; Cao, X.; Wu, Y.; Belda-Palazon, B.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Yang, S.; et al. ESCRT-I Component VPS23A Affects ABA Signaling by Recognizing ABA Receptors for Endosomal Degradation. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 1570–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.N.; Zeng, B.; Liu, H.S.; Qi, H.; Xie, L.J.; Yu, L.J.; Chen, Q.F.; Li, J.F.; Chen, Y.Q.; Jiang, L.; et al. SINAT E3 Ubiquitin Ligases Mediate FREE1 and VPS23A Degradation to Modulate Abscisic Acid Signaling. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3290–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Cao, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, Q.; Xia, R.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Q. ESCRT-I Component VPS23A Is Targeted by E3 Ubiquitin Ligase XBAT35 for Proteasome-Mediated Degradation in Modulating ABA Signaling. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1556–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liang, J.; Lou, L.; Tian, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Xia, R.; Wu, Y.; Xie, Q.; et al. The deubiquitinases UBP12 and UBP13 integrate with the E3 ubiquitin ligase XBAT35.2 to modulate VPS23A stability in ABA signaling. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Serio, R.J.; Schofield, A.; Liu, H.; Rasmussen, S.R.; Hofius, D.; Stone, S.L. Arabidopsis RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase XBAT35.2 promotes proteasome-dependent degradation of ACD11 to attenuate abiotic stress tolerance. Plant J. 2020, 104, 1712–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, M.A.; Belda-Palazon, B.; Julian, J.; Coego, A.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Iñigo, S.; Rodriguez, L.; Bueso, E.; Goossens, A.; Rodriguez, P.L. RBR-Type E3 Ligases and the Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme UBC26 Regulate Abscisic Acid Receptor Levels and Signaling. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Meng, J.; Chen, Z.; Xie, Q.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; et al. Degradation of the ABA co-receptor ABI1 by PUB12/13 U-box E3 ligases. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Peirats-Llobet, M.; Belda-Palazon, B.; Wang, X.; Cui, S.; Yu, X.; Rodriguez, P.L.; An, C. Ubiquitin Ligases RGLG1 and RGLG5 Regulate Abscisic Acid Signaling by Controlling the Turnover of Phosphatase PP2CA. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 2178–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, J.; Coego, A.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Lechner, E.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Merilo, E.; Belda-Palazon, B.; Park, S.Y.; Cutler, S.R.; et al. The MATH-BTB BPM3 and BPM5 subunits of Cullin3-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases target PP2CA and other clade A PP2Cs for degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 15725–15734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Wang, Z.; Ren, Z.; Zhi, L.; Yao, B.; Su, C.; Liu, L.; Li, X. SCFAtPP2-B11 modulates ABA signaling by facilitating SnRK2.3 degradation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Kim, J.K.; Jan, M.; Khan, H.A.; Khan, I.U.; Shen, M.; Park, J.; Lim, C.J.; Hussain, S.; Baek, D.; et al. Rheostatic Control of ABA Signaling through HOS15-Mediated OST1 Degradation. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1447–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Lv, M.; Cao, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, H. NUA and ESD4 negatively regulate ABA signaling during seed germination. Stress Biol. 2022, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.N.; Wang, Z.; Ren, Z.; Wang, C.H.; Wang, P.; Zhu, J.K.; Li, X.; Duan, C.G. NUCLEAR PORE ANCHOR and EARLY IN SHORT DAYS 4 negatively regulate abscisic acid signaling by inhibiting Snf1-related protein kinase2 activity and stability in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 2060–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.A.; Mudgil, Y.; Salt, J.N.; Delmas, F.; Ramachandran, S.; Chilelli, A.; Goring, D.R. Interactions between the S-domain receptor kinases and AtPUB-ARM E3 ubiquitin ligases suggest a conserved signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 2084–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Garreton, V.; Chua, N.H. The AIP2 E3 ligase acts as a novel negative regulator of ABA signaling by promoting ABI3 degradation. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 1532–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, S.; Jones, H.D.; Holdsworth, M.J. Interactions of the developmental regulator ABI3 with proteins identified from developing Arabidopsis seeds. Plant J. 2000, 21, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Stone, S.L. Cytoplasmic degradation of the Arabidopsis transcription factor abscisic acid insensitive 5 is mediated by the RING-type E3 ligase KEEP ON GOING. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 20267–20279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, S.L.; Williams, L.A.; Farmer, L.M.; Vierstra, R.D.; Callis, J. KEEP ON GOING, a RING E3 ligase essential for Arabidopsis growth and development, is involved in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 3415–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cui, F.; Wu, Y.; Lou, L.; Liu, L.; Tian, M.; Ning, Y.; Shu, K.; Tang, S.; Xie, Q. The RING finger ubiquitin E3 ligase SDIR1 targets SDIR1-INTERACTING PROTEIN1 for degradation to modulate the salt stress response and ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Zheng, N.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Q.; Gao, T.; Guo, H.; Xie, Q. SDIR1 is a RING finger E3 ligase that positively regulates stress-responsive abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1912–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Lee, J.; Jin, J.B.; Yoo, C.Y.; Miura, T.; Hasegawa, P.M. Sumoylation of ABI5 by the Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 negatively regulates abscisic acid signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5418–5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ma, L.; Liao, C. The Ubiquitin E3 Ligase RHA2b Promotes Degradation of MYB30 in Abscisic Acid Signaling. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G.; Seo, P.J. The Arabidopsis MIEL1 E3 ligase negatively regulates ABA signalling by promoting protein turnover of MYB96. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Schumaker, K.S.; Guo, Y. Sumoylation of transcription factor MYB30 by the small ubiquitin-like modifier E3 ligase SIZ1 mediates abscisic acid response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12822–12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, H.; Nkwe, N.S.; Estavoyer, B.; Messmer, C.; Gushul-Leclaire, M.; Villot, R.; Uriarte, M.; Boulay, K.; Hlayhel, S.; Farhat, B.; et al. An inventory of crosstalk between ubiquitination and other post-translational modifications in orchestrating cellular processes. iScience 2023, 26, 106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, L. Crosstalk between Ubiquitination and Other Post-translational Protein Modifications in Plant Immunity. Plant Commun. 2020, 1, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hoehenwarter, W. Changes in the Phosphoproteome and Metabolome Link Early Signaling Events to Rearrangement of Photosynthesis and Central Metabolism in Salinity and Oxidative Stress Response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 3021–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipčík, P.; Curry, J.R.; Mace, P.D. When Worlds Collide-Mechanisms at the Interface between Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubeaux, G.; Neveu, J.; Zelazny, E.; Vert, G. Metal Sensing by the IRT1 Transporter-Receptor Orchestrates Its Own Degradation and Plant Metal Nutrition. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 953–964.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, S.; Aoyama, S.; Hasegawa, Y.; Sato, T.; Yamaguchi, J. Arabidopsis CBL-Interacting Protein Kinases Regulate Carbon/Nitrogen-Nutrient Response by Phosphorylating Ubiquitin Ligase ATL31. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, S.; Sato, T.; Maekawa, S.; Aoyama, S.; Fukao, Y.; Yamaguchi, J. Phosphorylation of Arabidopsis ubiquitin ligase ATL31 is critical for plant carbon/nitrogen nutrient balance response and controls the stability of 14-3-3 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 15179–15193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Maekawa, S.; Yasuda, S.; Domeki, Y.; Sueyoshi, K.; Fujiwara, M.; Fukao, Y.; Goto, D.B.; Yamaguchi, J. Identification of 14-3-3 proteins as a target of ATL31 ubiquitin ligase, a regulator of the C/N response in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011, 68, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, P.; Ma, X.; Lin, W.; Chen, S.; Mishev, K.; Lu, D.; Kumar, R.; Vanhoutte, I.; et al. Regulation of Arabidopsis brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 endocytosis and degradation by plant U-box PUB12/PUB13-mediated ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1906–E1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Lin, W.; Gao, X.; Wu, S.; Cheng, C.; Avila, J.; Heese, A.; Devarenne, T.P.; He, P.; Shan, L. Direct ubiquitination of pattern recognition receptor FLS2 attenuates plant innate immunity. Science 2011, 332, 1439–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahpasandzadeh, H.; Popova, B.; Kleinknecht, A.; Fraser, P.E.; Outeiro, T.F.; Braus, G.H. Interplay between sumoylation and phosphorylation for protection against α-synuclein inclusions. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 31224–31240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffroy, M.C.; Hay, R.T. An additional role for SUMO in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Nelis, S.; Zhang, C.; Woodcock, A.; Swarup, R.; Galbiati, M.; Tonelli, C.; Napier, R.; Hedden, P.; Bennett, M.; et al. Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier protein SUMO enables plants to control growth independently of the phytohormone gibberellin. Dev. Cell 2014, 28, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Sun, W. Sumoylation stabilizes RACK1B and enhance its interaction with RAP2.6 in the abscisic acid response. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.T.; Wuerzberger-Davis, S.M.; Wu, Z.H.; Miyamoto, S. Sequential modification of NEMO/IKKgamma by SUMO-1 and ubiquitin mediates NF-kappaB activation by genotoxic stress. Cell 2003, 115, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda-Palazón, B.; Adamo, M.; Valerio, C.; Ferreira, L.J.; Confraria, A.; Reis-Barata, D.; Rodrigues, A.; Meyer, C.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Baena-González, E. A dual function of SnRK2 kinases in the regulation of SnRK1 and plant growth. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozet, P.; Margalha, L.; Butowt, R.; Fernandes, N.; Elias, C.A.; Orosa, B.; Tomanov, K.; Teige, M.; Bachmair, A.; Sadanandom, A.; et al. SUMOylation represses SnRK1 signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2016, 85, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Parker, J.E.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Schroeder, J.I. Genetic strategies for improving crop yields. Nature 2019, 575, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lin, Q.; Jin, S.; Gao, C. The CRISPR-Cas toolbox and gene editing technologies. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, R.; Niu, R.; Yang, R.; Xu, G. Engineering crop performance with upstream open reading frames. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardi, T.; Murovec, J.; Bakhsh, A.; Boniecka, J.; Bruegmann, T.; Bull, S.E.; Eeckhaut, T.; Fladung, M.; Galovic, V.; Linkiewicz, A.; et al. CRISPR/Cas-mediated plant genome editing: Outstanding challenges a decade after implementation. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 1144–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamthan, A.; Chaudhuri, A.; Kamthan, M.; Datta, A. Small RNAs in plants: Recent development and application for crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Li, P. SnapShot: Condensates in plant biology. Cell 2024, 187, 2894–2894.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis-Miranda, J.; Chodasiewicz, M.; Skirycz, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Moschou, P.N.; Bozhkov, P.V.; Gutierrez-Beltran, E. Stress-related biomolecular condensates in plants. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 3187–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruri-Lopez, I.; Chodasiewicz, M. Involvement of small molecules and metabolites in regulation of biomolecular condensate properties. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzianestis, I.H.; Mountourakis, F.; Stavridou, S.; Moschou, P.N. Plant condensates: No longer membrane-less? Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Su, T.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wong, C.E.; Ma, J.; Shao, Y.; Hua, C.; Shen, L.; Yu, H. N(6)-methyladenosine-mediated feedback regulation of abscisic acid perception via phase-separated ECT8 condensates in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Niu, R.; Tang, Z.; Mou, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Yang, H.; Ding, P.; Xu, G. Plant HEM1 specifies a condensation domain to control immune gene translation. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Shi, S.; Niu, R.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fu, R.; Mou, R.; Chen, S.; Ding, P.; Xu, G. Alleviating protein-condensation-associated damage at the endoplasmic reticulum enhances plant disease tolerance. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1552–1565.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, N.A.; Avin-Wittenberg, T.; Bassham, D.C.; Chen, P.; Chen, Q.; Fang, J.; Genschik, P.; Ghifari, A.S.; Guercio, A.M.; Gibbs, D.J.; et al. The lowdown on breakdown: Open questions in plant proteolysis. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 2931–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Abdel-Aziz, A.K.; Abdelfatah, S.; Abdellatif, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abel, S.; Abeliovich, H.; Abildgaard, M.H.; Abudu, Y.P.; Acevedo-Arozena, A.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition). Autophagy 2021, 17, 1–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhu, S.; Dang, H.; Wen, Q.; Niu, R.; Long, J.; Wang, Z.; Tong, Y.; Ning, Y.; Yuan, M.; et al. Genetically-encoded targeted protein degradation technology to remove endogenous condensation-prone proteins and improve crop performance. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Crews, C.M. PROTACs: Past, present and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5214–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Ngea, G.L.N.; Wang, K.; Lu, Y.; Godana, E.A.; Ackah, M.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H. Deciphering the mechanism of E3 ubiquitin ligases in plant responses to abiotic and biotic stresses and perspectives on PROTACs for crop resistance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2811–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, G.; Feng, B.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, T. Protein Post-Translational Modifications in Plant Abiotic Stress Responses. Plants 2026, 15, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010052

Li G, Feng B, Zhu Q-H, Jiang K, Zhang T. Protein Post-Translational Modifications in Plant Abiotic Stress Responses. Plants. 2026; 15(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Gengmi, Baohua Feng, Qian-Hao Zhu, Kaifeng Jiang, and Tao Zhang. 2026. "Protein Post-Translational Modifications in Plant Abiotic Stress Responses" Plants 15, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010052

APA StyleLi, G., Feng, B., Zhu, Q.-H., Jiang, K., & Zhang, T. (2026). Protein Post-Translational Modifications in Plant Abiotic Stress Responses. Plants, 15(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010052