Organic Compounds as a Natural Alternative for Pest Control: How Will Climate Change Affect Their Effectiveness?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

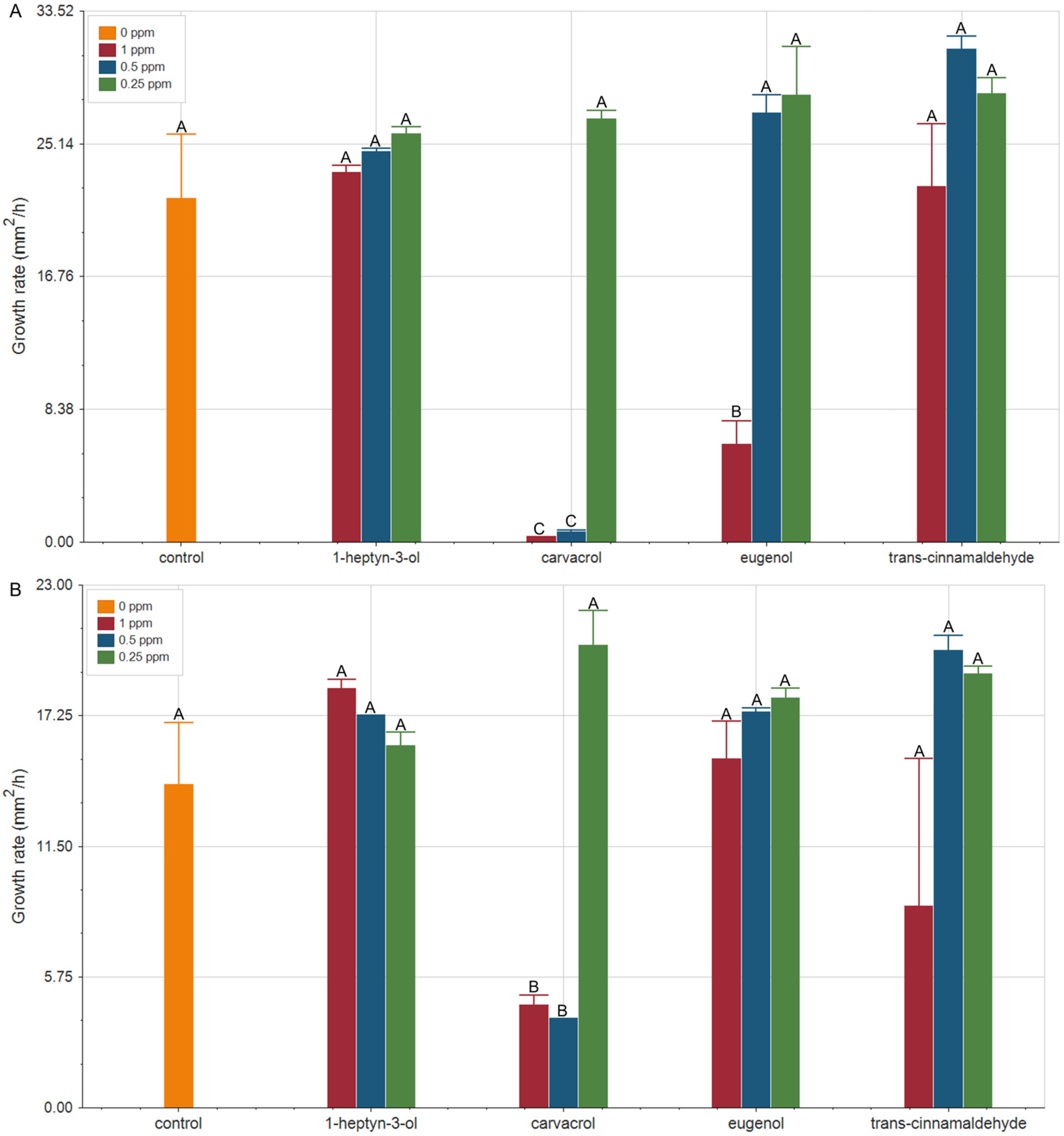

2.1. Carvacrol Retains Antifungal Efficacy Under Global Warming Conditions

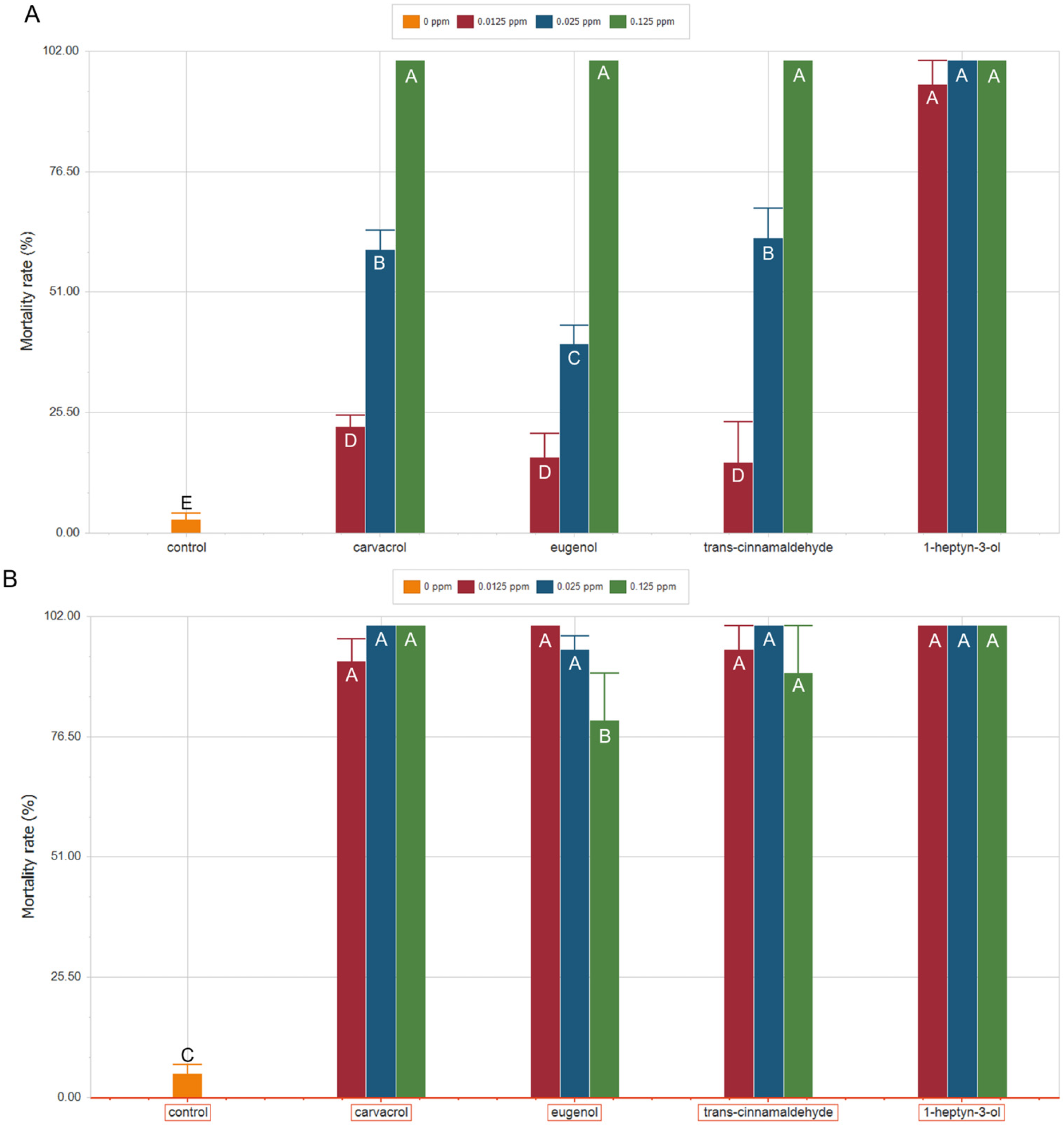

2.2. Increased Temperature Does Not Compromise, and Enhances, the Toxicity of Volatile Compounds Toward S. zeamais

3. Discussion

3.1. Sustained Efficacy of Carvacrol and Eugenol Against F. verticillioides Growth at Elevated Temperatures: Implications for Biocontrol on Climate Change Scenarios

3.2. Enhanced Efficacy of 1-Heptyn-3-ol, Carvacrol, Eugenol, and Trans-Cinnamaldehyde Against S. zeamais Under Global Warming Scenarios

4. Materials and Methods

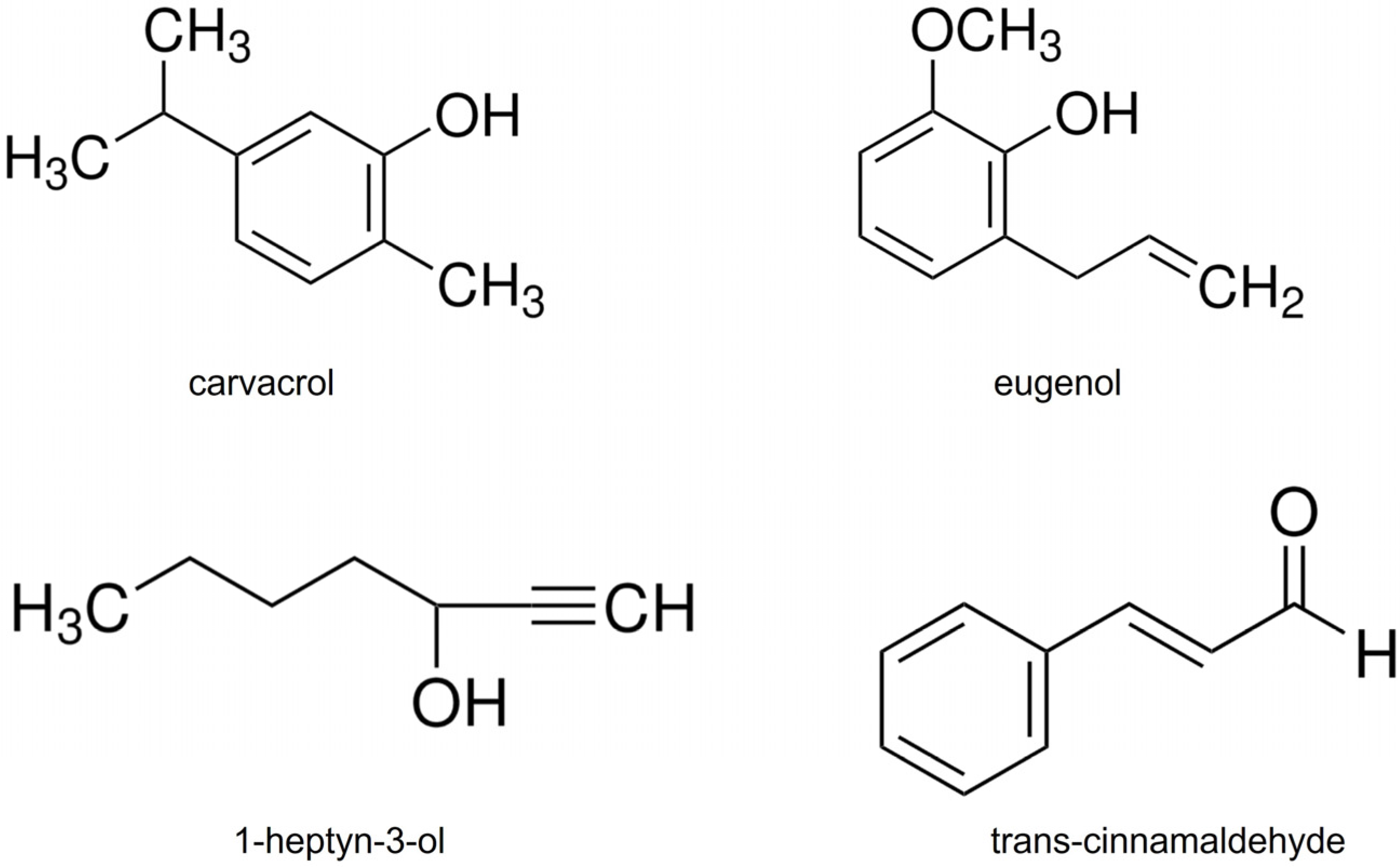

4.1. Fungal Strain, Insects, and Natural Organic Compounds

4.2. Climate Change Scenarios

4.3. Effect of Organic Compounds on Fungal Growth

4.4. Insecticidal Effect of Organic Compounds Against S. zeamais

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naciones Unidas C.C. COP25. Available online: https://unfccc.int/event/cop-25#eq-12 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Bezeng, B.S.; Yessoufou, K.; Taylor, P.J.; Tesfamichael, S.G. Expected Spatial Patterns of Alien Woody Plants in South Africa’s Protected Areas Under Current Scenario of Climate Change. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.W.L.; Frölicher, T.L. Marine Heatwaves Exacerbate Climate Change Impacts for Fisheries in the Northeast Pacific. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Racines, C.; Tarapues, J.; Thornton, P.; Jarvis, A.; Ramirez-Villegas, J. High-Resolution and Bias-Corrected CMIP5 Projections for Climate Change Impact Assessments. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauberger, B.; Archontoulis, S.; Arneth, A.; Balkovic, J.; Ciais, P.; Deryng, D.; Elliott, J.; Folberth, C.; Khabarov, N.; Müller, C.; et al. Consistent Negative Response of US Crops to High Temperatures in Observations and Crop Models. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchi, C.J.; Ruiz-Vera, U.M.; Siebers, M.H.; DeLucia, N.J.; Ort, D.R. Short- and Long-Term Warming Events on Photosynthetic Physiology, Growth, and Yields of Field Grown Crops. Biochem. J. 2023, 480, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Egidi, E.; Guirado, E.; Leach, J.E.; Liu, H.; Trivedi, P. Climate Change Impacts on Plant Pathogens, Food Security and Paths Forward. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, B.; Poudel, A.; Aryal, S. The Impact of Climate Change on Insect Pest Biology and Ecology: Implications for Pest Management Strategies, Crop Production, and Food Security. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Haxim, Y.; Islam, W.; Ahmad, M.; Muhammad, M.; Alqahtani, F.M.; Hashem, M.; Salih, H.; Zhang, D. Climate Change Reshaping Plant-Fungal Interaction. Environ. Res. 2023, 238, 117282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casu, A.; Camardo Leggieri, M.; Toscano, P.; Battilani, P. Changing Climate, Shifting Mycotoxins: A Comprehensive Review of Climate Change Impact on Mycotoxin Contamination. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable de la Nación. Tercera Comunicación Nacional Sobre Cambio Climático. “Cambio Climático En Argentina; Tendencias y Proyecciones”; Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable de la Nación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Donat, P.; Marín, S.; Sanchis, V.; Ramos, A.J. A Review of the Mycotoxin Adsorbing Agents, with an Emphasis on Their Multi-Binding Capacity, for Animal Feed Decontamination. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 114, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, C.A.; Tewksbury, J.J.; Tigchelaar, M.; Battisti, D.S.; Merrill, S.C.; Huey, R.B.; Naylor, R.L. Increase in Crop Losses to Insect Pests in a Warming Climate. Science 2018, 361, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, P.; Li, R.; Ma, P.; Wu, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, H. Increasing Fusarium Verticillioides Resistance in Maize by Genomics-Assisted Breeding: Methods, Progress, and Prospects. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1626–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, O.P.; Babalola, O.O. Fusarium Verticillioides of Maize Plant: Potentials of Propitious Phytomicrobiome as Biocontrol Agents. Front. Fungal Biol. 2023, 4, 1095765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wen, J.; Tang, Y.; Shi, J.; Mu, G.; Yan, R.; Cai, J.; Long, M. Research Progress on Fumonisin B1 Contamination and Toxicity: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, A.S.; Vinson, C.C.; Braga, L.S.; Guedes, R.N.C.; de Oliveira, L.O. Ancient Origin and Recent Range Expansion of the Maize Weevil Sitophilus zeamais, and Its Genealogical Relationship to the Rice Weevil S. Oryzae. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2016, 107, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita Devi, S.; Thomas, A.; Rebijith, K.B.; Ramamurthy, V.V. Biology, Morphology and Molecular Characterization of Sitophilus oryzae and S. zeamais (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 2017, 73, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demis, E.; Yenewa, W. Review on Major Storage Insect Pests of Cereals and Pulses. Asian J. Adv. Res. 2022, 12, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Usseglio, V.L.; Dambolena, J.S.; Martinez, M.J.; Zunino, M.P. The Role of Fumonisins in the Biological Interaction Between Fusarium verticillioides and Sitophilus zeamais. J. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 46, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, M.A.; Lizarraga, S.; Bruce, A.; Kim, T.N.; Morrison, W.R. Grain Inoculated with Different Growth Stages of the Fungus, Aspergillus flavus, Affect the Close-Range Foraging Behavior by a Primary Stored Product Pest, Sitophilus oryzae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ. Entomol. 2022, 51, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fai, P.B.A.; Ncheuveu, N.T.; Tchamba, M.N.; Ngealekeloeh, F. Ecological Risk Assessment of Agricultural Pesticides in the Highly Productive Ndop Flood Plain in Cameroon Using the PRIMET Model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 24885–24899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Fang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Jin, Y. The Toxicity and Health Risk of Chlorothalonil to Non-Target Animals and Humans: A Systematic Review. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosdoski, S.D.; Sinópolis Gigliolli, A.A.; Cabral, L.C.; Julio, A.H.F.; Bespalhok, D.D.N.; Santini, B.L.; Lapenta, A.S. Characterization of Esterases in the Involvement of Insecticide Resistance in Sitophilus oryzae and Sitophilus zeamais (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2024, 44, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, D.; de Oliveira, G.S.; Fernandes, M.G. Resistance Evaluation of Maize Varieties to Sitophilus zeamais Infestation Across Two Generations: Insights for Integrated Pest Management. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2024, 109, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razo-Belman, R.; Ozuna, C. Volatile Organic Compounds: A Review of Their Current Applications as Pest Biocontrol and Disease Management. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonks, A.J.; Roberts, J.M.; Midthassel, A.; Pope, T. Exploiting Volatile Organic Compounds in Crop Protection: A Systematic Review of 1-Octen-3-Ol and 3-Octanone. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2023, 183, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Adeleke, B.S.; Akinola, S.A.; Fayose, C.A.; Adeyemi, U.T.; Gbadegesin, L.A.; Omole, R.K.; Johnson, R.M.; Uthman, Q.O.; Babalola, O.O. Biopesticides as a Promising Alternative to Synthetic Pesticides: A Case for Microbial Pesticides, Phytopesticides, and Nanobiopesticides. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1040901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, Á.; Rodríguez, A.; Magan, N. Climate Change and Mycotoxigenic Fungi: Impacts on Mycotoxin Production. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 5, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshelia, P.L.; Selamat, J.; Iskandar Putra Samsudin, N.; Rafii, M.Y.; Abdul Mutalib, N.A.; Nordin, N.; Berthiller, F. Effect of Temperature, Water Activity and Carbon Dioxide on Fungal Growth and Mycotoxin Production of Acclimatised Isolates of Fusarium verticillioides and F. Graminearum. Toxins 2020, 12, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgrò, C.M.; Terblanche, J.S.; Hoffmann, A.A. What Can Plasticity Contribute to Insect Responses to Climate Change? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2016, 61, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, Y.K.; Beldade, P. Thermal Plasticity in Insects’ Response to Climate Change and to Multifactorial Environments. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I.P.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Insect Pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambolena, J.S.; López, A.G.; Meriles, J.M.; Rubinstein, H.R.; Zygadlo, J.A. Inhibitory Effect of 10 Natural Phenolic Compounds on Fusarium verticillioides. A Structure–Property–Activity Relationship Study. Food Control 2012, 28, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Ju, J. Carvacrol Induces Apoptosis in Aspergillus niger Through ROS Burst. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divband, K.; Shokri, H.; Khosravi, A.R. Down-Regulatory Effect of Thymus Vulgaris L. on Growth and Tri4 Gene Expression in Fusarium oxysporum Strains. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 104, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campaniello, D.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Antifungal Activity of Eugenol Against Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Fusarium Species. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Spiegel, M.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Marvin, H.J.P. Effects of Climate Change on Food Safety Hazards in the Dairy Production Chain. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Bi, Y.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y.; Zong, Y.; Prusky, D. Antifungal Activity of Cinnamaldehyde Against Fusarium sambucinum Involves Inhibition of Ergosterol Biosynthesis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo Jimenez, B.A.; Awwad, F.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Cinnamaldehyde in Focus: Antimicrobial Properties, Biosynthetic Pathway, and Industrial Applications. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.R.; Hu, H.J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.X.; Zhu, X.D.; Ma, J.W.; Liu, Y.Q. Cinnamaldehyde Acts as a Fungistat by Disrupting the Integrity of Fusarium oxysporum Fox-1 Cell Membranes. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cao, H.; Zhang, D. Structure-Activity Relationships of Cinnamaldehyde and Eugenol Derivatives Against Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 97, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, Z.; Sun, H. Antifungal Activities and Mechanisms of Trans-cinnamaldehyde and Thymol Against Food-spoilage Yeast Zygosaccharomyces rouxii. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 1197–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, V.D.; Achimón, F.; Zunino, M.P.; Pizzolitto, R.P. Control of Fusarium verticillioides in Maize Stored in Silo Bags with 1-Octyn-3-Ol. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2024, 106, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.C.; Beato, M.; Usseglio, V.L.; Merlo, C.; Zunino, M.P. Bioactive Paints with Volatile Organic Alcohols for the Control of Sitophilus zeamais. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2024, 109, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.W.; Yarbrough, J.W. Trends in Structure–Toxicity Relationships for Carbonyl-Containing α,β-Unsaturated Compounds. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2004, 15, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R. Química, 9th ed.; Mc Graw Hill Interamericana: Columbus, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dambolena, J.S.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Rubinstein, H.R. Antifumonisin Activity of Natural Phenolic CompoundsA Structure–Property–Activity Relationship Study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohman, B.; Nordlander, G.; Nordenhem, H.; Sunnerheim, K.; Borg-Karlson, A.-K.; Unelius, C.R. Structure–Activity Relationships of Phenylpropanoids as Antifeedants for the Pine Weevil hylobius Abietis. J. Chem. Ecol. 2008, 34, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struck, S.; Schmidt, U.; Gruening, B.; Jaeger, I.S.; Hossbach, J.; Preissner, R. Toxicity vs Potency: Elucidation of Toxicity Properties Discriminating Between Toxins, Drugs, and Natural Compounds. Genome Inform. 2008, 20, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Gu, L.; McClung, A.M.; Bergman, C.J.; Chen, M. Free and Bound Total Phenolic Concentrations, Antioxidant Capacities, and Profiles of Proanthocyanidins and Anthocyanins in Whole Grain Rice (Oryza sativa L.) of Different Bran Colours. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaio, Y.P.; Gatti, G.; Ponce, A.; Saavedra Larralde, N.A.; Martinez, M.J.; Zunino, M.P.; Zygadlo, J.A. Cinnamaldehyde and Related Phenylpropanoids, Natural Repellents, and Insecticides Against Sitophilus zeamais (Motsch.). A Chemical Structure-Bioactivity Relationship. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 5822–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaubey, M.K.; Kumar, N. Role of Carvacrol and Menthone in Maize Weevil Sitophilus zeamais (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Management. Eur. J. Biol. Res. 2023, 13, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Beato, M.; Usseglio, V.L.; Camina, J.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Dambolena, J.S.; Zunino, M.P. Phenolic Compounds as Controllers of Sitophilus zeamais: A Look at the Structure-Activity Relationship. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2022, 99, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.M.G.; Abou-Taleb, H.K.; Abdelgaleil, S.A.M. Insecticidal Activities of Monoterpenes and Phenylpropenes Against Sitophilus oryzae and Their Inhibitory Effects on Acetylcholinesterase and Adenosine Triphosphatases. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2018, 53, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ho, S.H.; Lee, H.C.; Yap, Y.L. Insecticidal Properties of Eugenol, Isoeugenol and Methyleugenol and Their Effects on Nutrition of Sitophilus zeamais Motsch. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 2002, 38, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Long, X.; Huang, A.; Zhang, J.; Geng, J.; Yang, L.; Huang, Z.; Dong, P.; et al. Inhibitory Effects and Mechanisms of Cinnamaldehyde Against Fusarium oxysporum, a Serious Pathogen in Potatoes. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 3540–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.M.G.; Abdelgaleil, S.A.M. Effectiveness of Monoterpenes and Phenylpropenes on Sitophilus oryzae L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Stored Wheat. J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 2018, 21, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, M.K. Insecticidal Activities of Natural Volatile Compounds Against Pulse Beetle, Callosobruchus Chinensis (Bruchidae). Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2024, 46, e68787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beament, J.W.L. The Waterproofing Mechanism of Arthropods. J. Exp. Biol. 1959, 36, 391–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neven, L.G. Physiological Responses of Insects to Heat. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2000, 21, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipupo, S.O.; Wilson, A.E.; Hu, X.P.; Appel, A.G. Why Do Insects Close Their Spiracles? A Meta-Analytic Evaluation of the Adaptive Hypothesis of Discontinuous Gas Exchange in Insects. Insects 2022, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J.; Summerel, B.A. Species Concepts in Fusarium. In Fusarium Laboratory Manual; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 88–95. ISBN 9780470278376. [Google Scholar]

- Dambolena, J.S.; López, A.G.; Cánepa, M.C.; Theumer, M.G.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Rubinstein, H.R. Inhibitory Effect of Cyclic Terpenes (Limonene, Menthol, Menthone and Thymol) on Fusarium verticillioides MRC 826 Growth and Fumonisin B1 Biosynthesis. Toxicon 2008, 51, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usseglio, V.L.; Dambolena, J.S.; Merlo, C.; Peschiutta, M.L.; Zunino, M.P. Insect-Corn Kernel Interaction: Chemical Signaling of the Grain and Host Recognition by Sitophilus zeamais. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2018, 79, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhang, H.; Xu, R.; Chang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xiang, H.; Li, Y. Inhibitory Effect of Eugenol on Fusarium oxysporum and Transcriptome Analysis. Tob. Sci. Technol. 2025, 58, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio Meteorológico Nacional Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Available online: https://www.smn.gob.ar/ (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Pizzolitto, R.P.; Jacquat, A.G.; Usseglio, V.L.; Achimón, F.; Cuello, A.E.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Dambolena, J.S. Quantitative-Structure-Activity Relationship Study to Predict the Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils Against Fusarium verticillioides. Food Control 2020, 108, 106836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.M.; Zunino, M.P.; Dambolena, J.S.; Pizzolitto, R.P.; Gañan, N.A.; Lucini, E.I.; Zygadlo, J.A. Terpene Ketones as Natural Insecticides Against Sitophilus zeamais. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 70, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, J.A. Navure Professional+ Version 3.0. 2024. Available online: https://www.navure.com/inicio/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- FAO-ONU Las Interacciones En La Agroecología. 2016. Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/8a99dfd7-e8e1-452f-b61b-abb1966887b4/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Rodríguez, D.A. Interacciones Bióticas de Los Agroecosistemas del Semiárido Bonaerense. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional del Sur, Bahía Blanca, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mossa, A.T.H. Green Pesticides: Essential Oils as Biopesticides in Insect-Pest Management. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 354–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B. Botanical Insecticides in the Twenty-First Century-Fulfilling Their Promise? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B. Plant Essential Oils for Pest and Disease Management. In Crop Protection; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 19, pp. 603–608. ISBN 1604822864. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Dikshit, A.K. Biopesticides: An Ecofriendly Approach for Pest Control. J. Biopestic. 2010, 3, 186–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pavela, R.; Benelli, G. Essential Oils as Ecofriendly Biopesticides? Challenges and Constraints. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Usseglio, V.L.; Zunino, M.P.; Brito, V.D.; Beato, M.; Theumer, M.G.; Dambolena, J.S. Organic Compounds as a Natural Alternative for Pest Control: How Will Climate Change Affect Their Effectiveness? Plants 2026, 15, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010048

Usseglio VL, Zunino MP, Brito VD, Beato M, Theumer MG, Dambolena JS. Organic Compounds as a Natural Alternative for Pest Control: How Will Climate Change Affect Their Effectiveness? Plants. 2026; 15(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleUsseglio, Virginia L., María P. Zunino, Vanessa D. Brito, Magalí Beato, Martin G. Theumer, and José S. Dambolena. 2026. "Organic Compounds as a Natural Alternative for Pest Control: How Will Climate Change Affect Their Effectiveness?" Plants 15, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010048

APA StyleUsseglio, V. L., Zunino, M. P., Brito, V. D., Beato, M., Theumer, M. G., & Dambolena, J. S. (2026). Organic Compounds as a Natural Alternative for Pest Control: How Will Climate Change Affect Their Effectiveness? Plants, 15(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010048