Genome-Wide Identification of the Double B-Box (DBB) Family in Three Cotton Species and Functional Analysis of GhDBB22 Under Salt Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

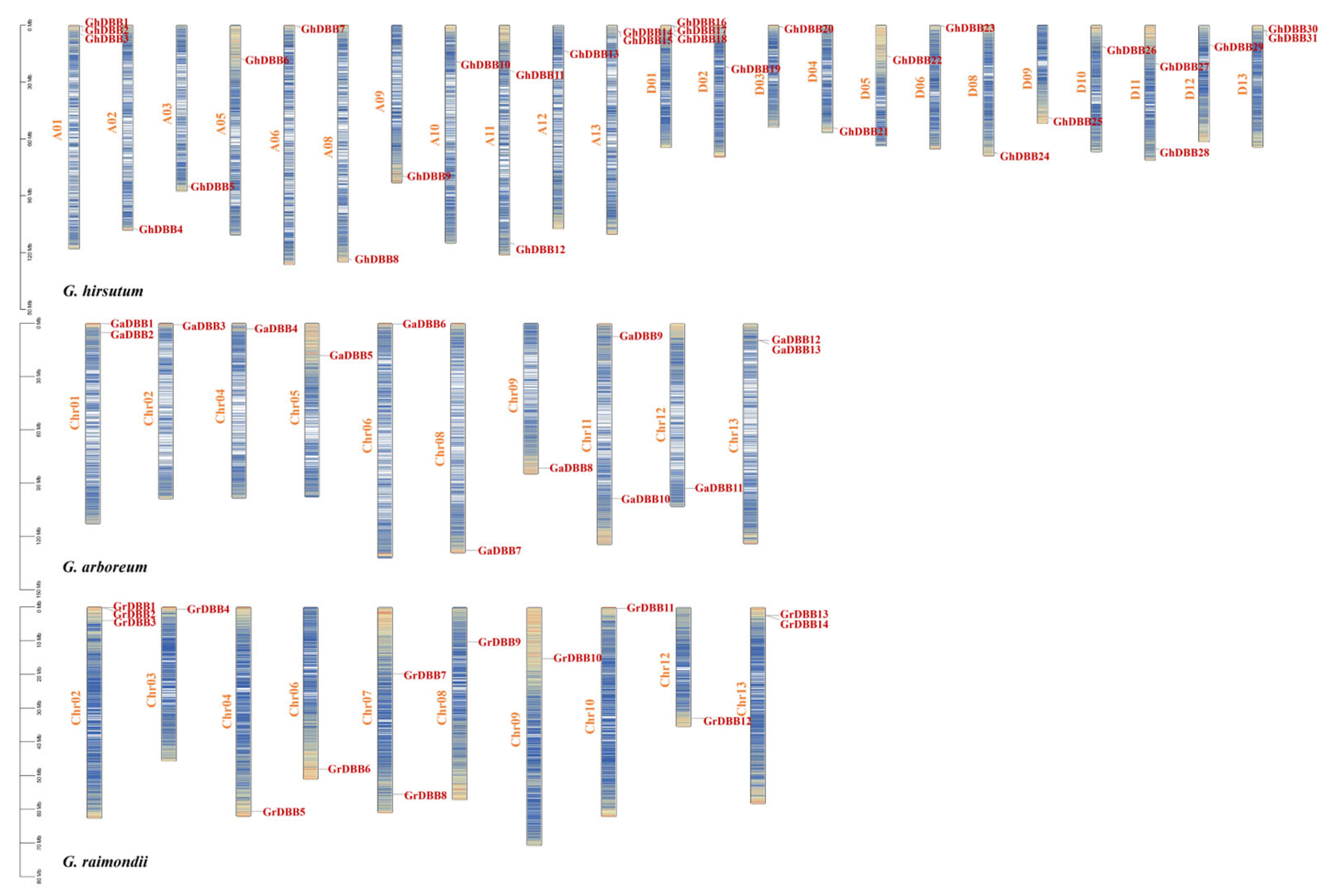

2.1. Identification of DBB Members in Three Cotton Species

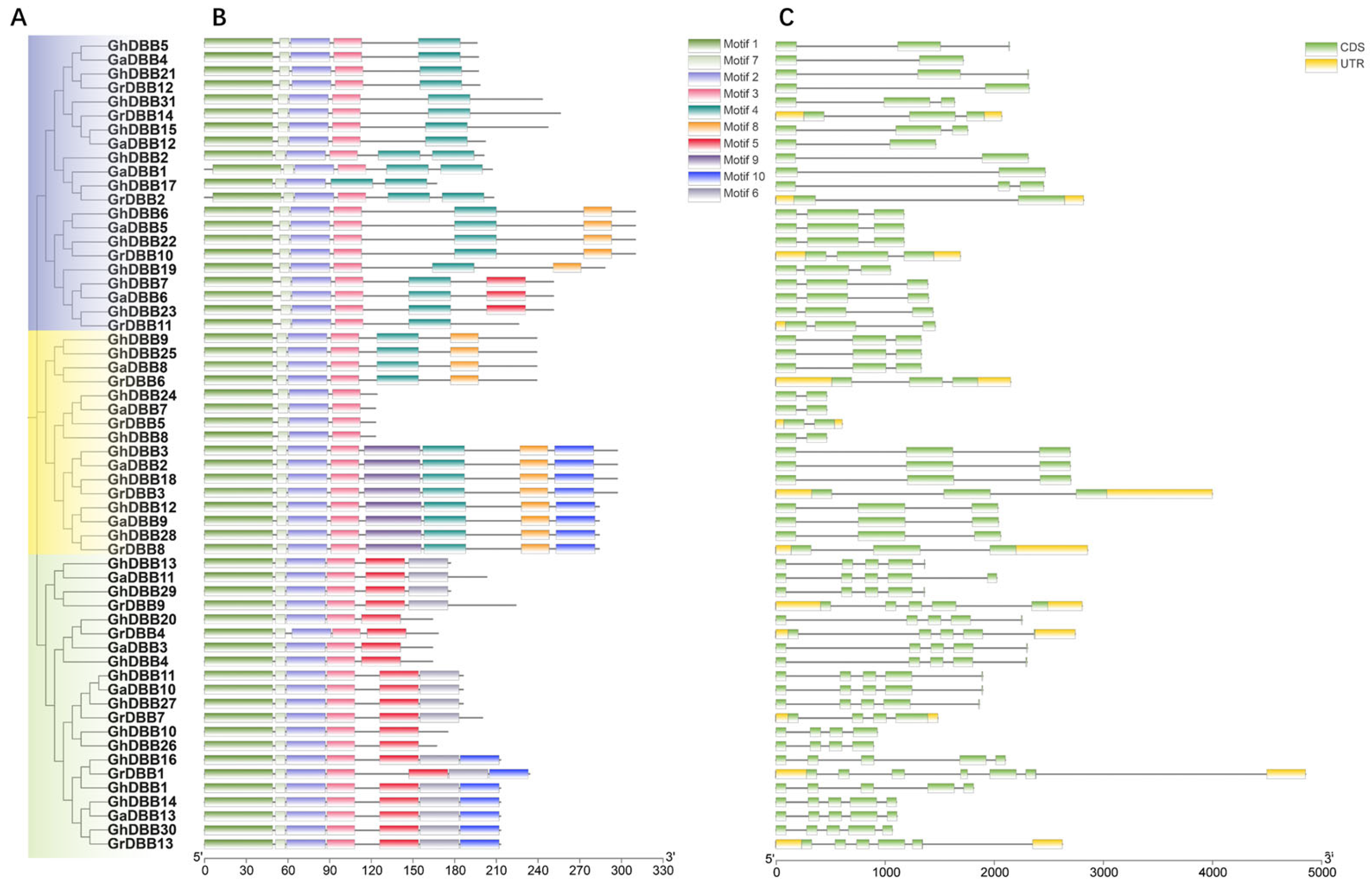

2.2. Phylogenetic Relationship of DBBs

2.3. Gene Structure and Motifs in DBBs

2.4. Gene Replication and Collinearity Analysis of DBBs in Cotton

2.5. The Distribution of Cis-Acting Elements in the Cotton DBB Promoters

2.6. Expression Characteristics of GhDBBs

2.7. Heterologous Expression of GhDBB22 Enhanced Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis

2.8. Silencing of GhDBB22 Impaired Salt Tolerance in Upland Cotton

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of DBB Family Members

4.2. Analysis of the Physicochemical Properties and Chromosomal Physical Location Distribution of DBB Family Members

4.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of DBBs

4.4. Analysis of the Gene Structure Characteristics and Motifs of DBBs

4.5. Collinearity Analysis of the DBBs in Cotton

4.6. Prediction of Cis-Acting Elements of the DBBs

4.7. Expression Characteristic Analysis and qPCR Verification of GhDBBs

4.8. Obtainment of Arabidopsis with Heterologous Expression of GhDBB22 and Identification of Its Salt Tolerance

4.9. Salt Tolerance Evaluation of Upland Cotton Following GhDBB22 Silencing via VIGS

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhou, H.; Ma, C.; Wang, P. Regulation of Plant Responses to Salt Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J. Genet. Genom. 2024, 51, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xia, M.; Su, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, L.; Zhao, H.; Gao, W.; Huang, L.; Hu, Y. MYB transcription factors in plants: A comprehensive review of their discovery, structure, classification, functional diversity and regulatory mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liao, J.; Chen, Q.; Jin, W.; Li, S.; Zhu, T.; Li, S. Identification and Characterization of the BBX Gene Family in Bambusa pervariabilis × Dendrocalamopsis grandis and Their Potential Role under Adverse Environmental Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, B.; Shi, X.; Niu, R.; Lin, F. Multi-layered roles of BBX proteins in plant growth and development. Stress Biol. 2023, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talar, U.; Kiełbowicz-Matuk, A. Beyond Arabidopsis: BBX Regulators in Crop Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Chen, C.; Xu, M.; Wang, G.; Xu, L.-A.; Wu, Y. Overexpression of Ginkgo BBX25 enhances salt tolerance in Transgenic Populus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Holm, M.; Deng, X.W. The B-Box Domain Protein BBX21 Promotes Photomorphogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2017, 176, 2365–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Shao, A.; Wei, M.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W. Genome-wide characterization of the BBX gene family in perennial ryegrass and functional insights into the potentiality of LpBBX3 in drought and salt tolerance. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 302, 118753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangappa, S.N.; Botto, J.F. The BBX family of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Kronmiller, B.; Maszle, D.R.; Coupland, G.; Holm, M.; Mizuno, T.; Wu, S.-H. The Arabidopsis B-Box Zinc Finger Family. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3416–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zeng, J.; Deng, K.; Tu, X.; Zhao, X.; Tang, D.; Liu, X. DBB1a, involved in gibberellin homeostasis, functions as a negative regulator of blue light-mediated hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Planta 2011, 233, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangappa, S.N.; Crocco, C.D.; Johansson, H.; Datta, S.; Hettiarachchi, C.; Holm, M.; Botto, J.F. The Arabidopsis B-BOX Protein BBX25 Interacts with HY5, Negatively Regulating BBX22 Expression to Suppress Seedling Photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-S.J.; Maloof, J.N.; Wu, S.-H. COP1-Mediated Degradation of BBX22/LZF1 Optimizes Seedling Development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tu, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Rao, L. Heat stress-induced BBX18 negatively regulates the thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 2679–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Li, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Meng, Z. Expression analysis of genes encoding double B-box zinc finger proteins in maize. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2017, 17, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Sun, J.; Liu, J.; Ren, H.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Dehesh, K. The B-box protein BBX19 suppresses seed germination via induction of ABI5. Plant J. 2019, 99, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaoka, S.; Takano, T. Salt tolerance-related protein STO binds to a Myb transcription factor homologue and confers salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 2231–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, X.; Weng, X.; Wang, L.; Xie, W. The rice B-box zinc finger gene family: Genomic identification, characterization, expression profiling and diurnal analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, H.; Ni, J.; Yang, T.; Lv, X.; Ren, K.; Xu, X.; Yang, C.; Dai, X.; Zeng, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization and Expression Patterns of the DBB Transcription Factor Family Genes in Wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, R.; Xu, K.; Liu, Y. The DBB Family in Populus trichocarpa: Identification, Characterization, Evolution and Expression Profiles. Molecules 2024, 29, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryum, Z.; Luqman, T.; Nadeem, S.; Khan, S.; Wang, B.; Ditta, A.; Khan, M.K.R. An overview of salinity stress, mechanism of salinity tolerance and strategies for its management in cotton. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 907937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Fang, L.; Guan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Saski, C.A.; Scheffler, B.E.; Stelly, D.M.; et al. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Bao, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhai, J.; Wendel, J.F.; Cao, X.; Zhu, Y. A telomere-to-telomere cotton genome assembly reveals centromere evolution and a Mutator transposon-linked module regulating embryo development. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 1953–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wu, Z.; Percy, R.G.; Bai, M.; Li, Y.; Frelichowski, J.E.; Hu, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, J.Z.; Zhu, Y. Genome sequence of Gossypium herbaceum and genome updates of Gossypium arboreum and Gossypium hirsutum provide insights into cotton A-genome evolution. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, R.; Srivastava, R.; Gunapati, S.; Sane, A.P.; Sane, V.A. Functional characterization of GhNAC2 promoter conferring hormone- and stress-induced expression: A potential tool to improve growth and stress tolerance in cotton. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiełbowicz-Matuk, A.; Rey, P.; Rorat, T. Interplay between circadian rhythm, time of the day and osmotic stress constraints in the regulation of the expression of a Solanum Double B-box gene. Ann. Bot. 2014, 113, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishak, K.P.; Yadukrishnan, P.; Bakshi, S.; Kushwaha, A.K.; Ramachandran, H.; Job, N.; Babu, D.; Datta, S. The B-box bridge between light and hormones in plants. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 191, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Pu, X. ZF-HD gene family in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.): Genome-wide identification, phylogeny, evolutionary expansion and expression analyses. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Dudhate, A.; Shinde, H.S.; Takano, T.; Tsugama, D. Phylogenetic trees, conserved motifs and predicted subcellular localization for transcription factor families in pearl millet. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y. NACs, generalist in plant life. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 2433–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.-h.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME Suite: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Fang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, W.; Niu, Y.; Ju, L.; Deng, J.; Zhao, T.; Lian, J.; et al. Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, A.H.; Wendel, J.F.; Gundlach, H.; Guo, H.; Jenkins, J.; Jin, D.; Llewellyn, D.; Showmaker, K.C.; Shu, S.; Udall, J.; et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature 2012, 492, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; You, F.M.; Datla, R.; Ravichandran, S.; Jia, B.; Cloutier, S. Genome-wide identification of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter and heavy metal associated (HMA) gene families in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ma, X.; Liu, S.; Du, B.; Cheng, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. The Nicotiana tabacum L. major latex protein-like protein 423 (NtMLP423) positively regulates drought tolerance by ABA-dependent pathway. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Nazir, F.; Maheshwari, C.; Kaur, H.; Gupta, R.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Khan, M.I.R. Plant hormones and secondary metabolites under environmental stresses: Enlightening defense molecules. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriotto, T.S.; Saura-Sánchez, M.; Barraza, C.; Botto, J.F. BBX24 Increases Saline and Osmotic Tolerance through ABA Signaling in Arabidopsis Seeds. Plants 2023, 12, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Li, J.; Gangappa, S.N.; Hettiarachchi, C.; Lin, F.; Andersson, M.X.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, X.W.; Holm, M. Convergence of Light and ABA signaling on the ABI5 promoter. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, S.; Song, Z.-T.; Jiang, Y.; Han, J.-J.; Lu, S.-J.; Li, L.; Liu, J.-X. Two B-Box Domain Proteins, BBX18 and BBX23, Interact with ELF3 and Regulate Thermomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1718–1728.e1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.; Park, J.; Kim, S.; Park, J.; Seo, D.; Oh, E. Overexpression of BBX18 Promotes Thermomorphogenesis Through the PRR5-PIF4 Pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 782352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ocampo, G.; Ploschuk, E.L.; Mantese, A.; Crocco, C.D.; Botto, J.F. BBX21 reduces abscisic acid sensitivity, mesophyll conductance and chloroplast electron transport capacity to increase photosynthesis and water use efficiency in potato plants cultivated under moderated drought. Plant J. 2021, 108, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Cheng, S.; Liu, F.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Xiong, X.; Sun, J. Genome-wide analysis of cotton SCAMP genes and functional characterization of GhSCAMP2 and GhSCAMP4 in salt tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Yin, G.; Chai, M.; Sun, L.; Wei, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, S. Systematic analysis of CNGCs in cotton and the positive role of GhCNGC32 and GhCNGC35 in salt tolerance. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hua, R.; Liu, H.; Sui, S. CpBBX19, a B-Box Transcription Factor Gene of Chimonanthus praecox, Improves Salt and Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Genes 2021, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Huang, G.; He, S.; Yang, Z.; Sun, G.; Ma, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Resequencing of 243 diploid cotton accessions based on an updated A genome identifies the genetic basis of key agronomic traits. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artico, S.; Nardeli, S.M.; Brilhante, O.; Grossi-de-Sa, M.F.; Alves-Ferreira, M. Identification and evaluation of new reference genes in Gossypium hirsutum for accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, S.J.; Bent, A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium -mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Sun, H.; Hakim; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. A novel cotton WRKY gene, GhWRKY6-like, improves salt tolerance by activating the ABA signaling pathway and scavenging of reactive oxygen species. Physiol. Plant. 2018, 162, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Yang, J.; He, M.; Wang, N.; Liu, J.; Song, J.; Yu, L.; Chi, W.; Song, X. Genome-Wide Identification of the Double B-Box (DBB) Family in Three Cotton Species and Functional Analysis of GhDBB22 Under Salt Stress. Plants 2026, 15, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010109

Zhang H, Wu X, Yang J, He M, Wang N, Liu J, Song J, Yu L, Chi W, Song X. Genome-Wide Identification of the Double B-Box (DBB) Family in Three Cotton Species and Functional Analysis of GhDBB22 Under Salt Stress. Plants. 2026; 15(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Haijun, Xuerui Wu, Jiahao Yang, Mengxue He, Na Wang, Jie Liu, Jinnan Song, Liyan Yu, Wenjuan Chi, and Xianliang Song. 2026. "Genome-Wide Identification of the Double B-Box (DBB) Family in Three Cotton Species and Functional Analysis of GhDBB22 Under Salt Stress" Plants 15, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010109

APA StyleZhang, H., Wu, X., Yang, J., He, M., Wang, N., Liu, J., Song, J., Yu, L., Chi, W., & Song, X. (2026). Genome-Wide Identification of the Double B-Box (DBB) Family in Three Cotton Species and Functional Analysis of GhDBB22 Under Salt Stress. Plants, 15(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010109