Distribution Characteristics and Adaptation Mechanisms of Exotic Spontaneous Plant Diversity in Urban Road Green Spaces of Changchun, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of Species Diversity Composition of Exotic Spontaneous Plants

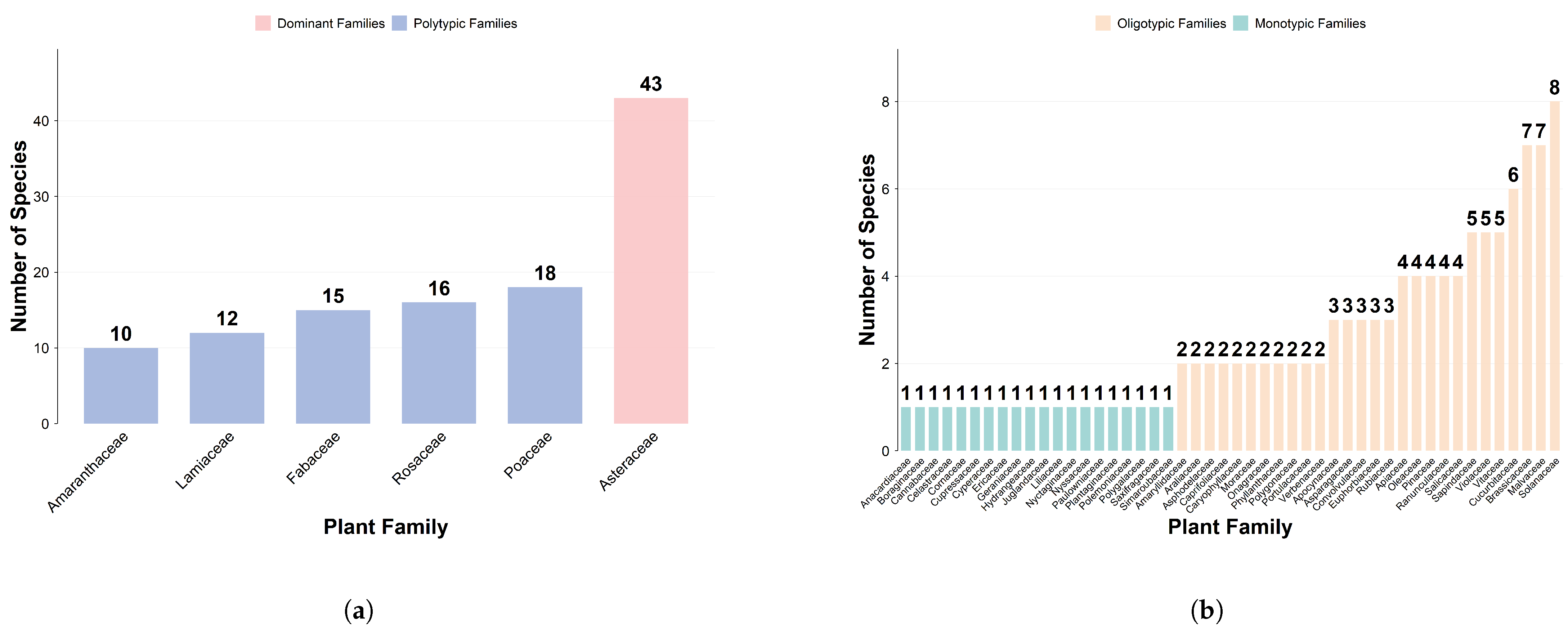

2.1.1. Analysis of Family-Genus Composition and Geographical Elements

2.1.2. Composition Characteristics of Dominant Species and High-Frequency Species

2.2. Distribution Pattern of Exotic Spontaneous Plant Diversity

2.2.1. Diversity Distribution Characteristics of Exotic Spontaneous Plants in Different Habitats

2.2.2. Diversity Distribution Characteristics of Exotic Spontaneous Plants Across Different Urbanization Levels

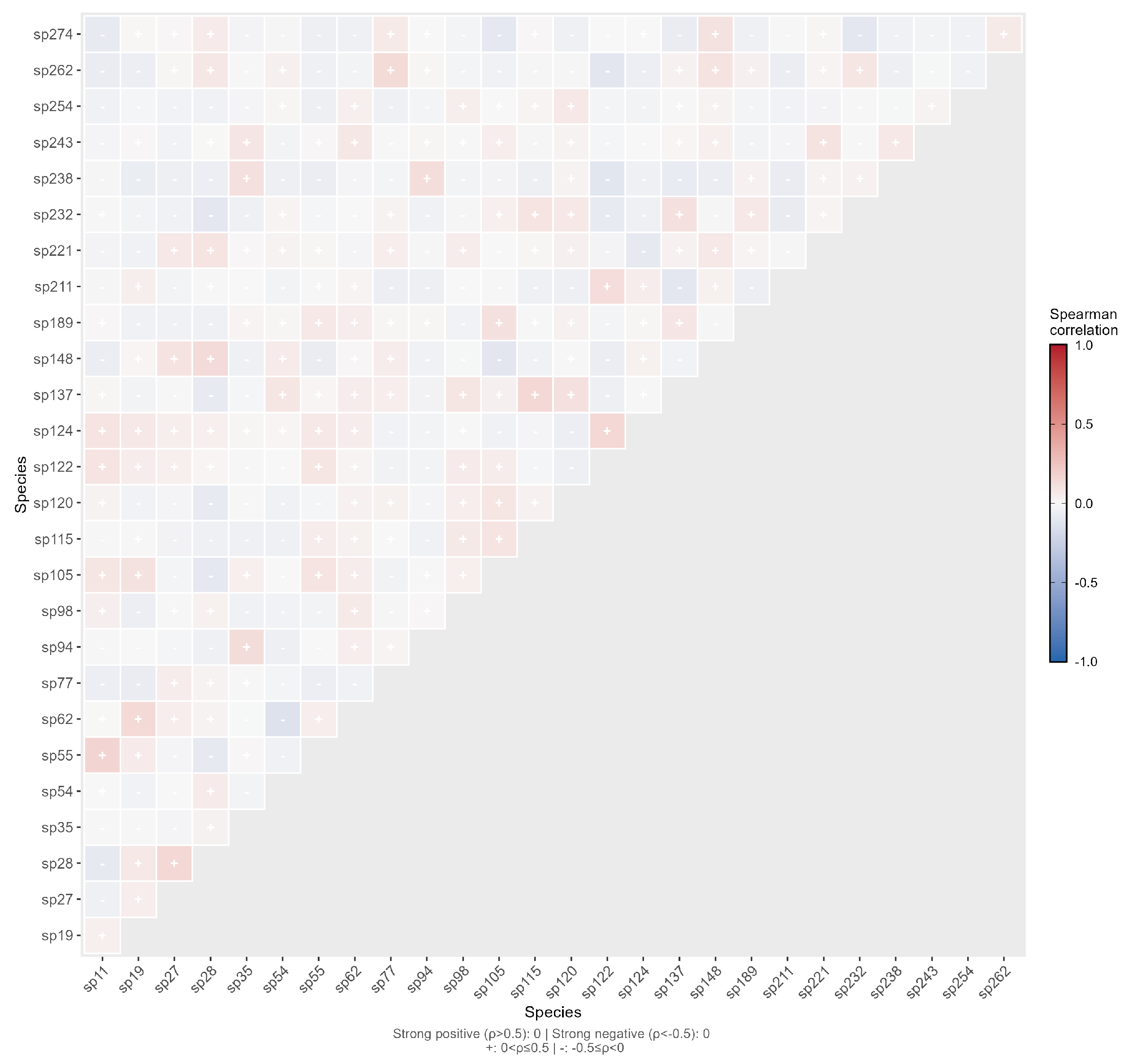

2.3. Interspecific Relationships Between Exotic Spontaneous Plants and Native Spontaneous Plants

2.4. Interaction Relationships of Diversity Between Exotic Spontaneous Plants and Native Spontaneous Plants

3. Discussion

3.1. Composition Characteristics of Species Diversity of Exotic Spontaneous Plants in Road Green Spaces

3.2. Adaptation Strategies of Exotic Spontaneous Plants Across Different Habitat Types and Urbanization Levels

3.3. Diversity and Interspecific Relationships Between Exotic and Native Spontaneous Plants in Road Green Spaces

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Overview of the Study Area

4.2. Research Methods

4.2.1. Plot Setup

4.2.2. Habitat Type Classification

4.2.3. Classification of Urbanization Level and Disturbance Intensity

4.3. Data Processing

- Relative Frequency (RF) = Frequency of a certain species in the quadrat/Sum of frequencies of all species

- Relative Coverage (RC) = Coverage of a certain species in the quadrat/Sum of coverages of all species

- : Shannon-Weiner diversity index

- S: total number of species

- : relative abundance of the i-th species,

- : number of individuals of species i

- N: total number of individuals,

- J: Pielou evenness index (ranges from 0 to 1)

- : observed Shannon-Weiner diversity index

- : maximum possible diversity,

- S: total number of species

- D: Simpson dominance index (ranges from 0 to 1)

- : relative abundance of the i-th species,

- S: total number of species

- is the probability of presence (either alien or native species) in plot i within habitat type j

- is the intercept (baseline log-odds when all predictors are 0)

- , , are coefficients for habitat types (with reference level encoded in the model matrix)

- , , are indicator variables for the three habitat types

- is the error term

4.4. -Diversity Differences Among Habitats (Linear Models)

- is the transformed diversity index value for:

- -

- Species richness:

- -

- Shannon index:

- -

- Pielou’s evenness: (no transformation, range 0–1)

- -

- Simpson’s index: (no transformation, range 0–1)

- is the overall mean

- is the fixed effect of habitat type j ()

- is the residual error, assumed normally distributed with mean 0 and variance

4.5. Diversity Trends Along Urbanization Gradient (Linear Regression)

- is the transformed diversity index (same transformations as above)

- X is the numerical urbanization gradient: City Center = 1, Middle Suburbs = 2, Outer Suburbs = 3

- is the intercept

- is the slope coefficient representing the linear trend

- is the error term

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Species Code | Latin Name |

|---|---|

| sp11 | Echinochloa crus-galli |

| sp19 | Polygonum aviculare |

| sp27 | Potentilla supina |

| sp28 | Plantago asiatica |

| sp35 | Cirsium arvense var. integrifolium |

| sp54 | Stellaria media |

| sp55 | Amaranthus retroflexus |

| sp62 | Setaria viridis |

| sp77 | Youngia japonica |

| sp94 | Sonchus wightianus |

| sp98 | Sonchus oleraceus |

| sp105 | Chenopodium album |

| sp115 | Solanum nigrum |

| sp120 | Cynanchum rostellatum |

| sp122 | Portulaca oleracea |

| sp124 | Digitaria sanguinalis |

| sp137 | Galinsoga parviflora |

| sp148 | Taraxacum mongolicum |

| sp189 | Acalypha australis |

| sp211 | Polygonum plebeium |

| sp221 | Erigeron canadensis |

| sp232 | Commelina communis |

| sp238 | Glycine soja |

| sp243 | Lactuca serriola |

| sp254 | Ulmus pumila |

| sp262 | Viola prionantha |

| sp274 | Ixeris chinensis |

References

- Blackburn, T.M.; Pysek, P.; Bacher, S.; Carlton, J.T.; Duncan, R.P.; Jarosik, V.; Wilson, J.R.U.; Richardson, D.M. A proposed unified framework for biological invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Yu, S.; Tang, S.; Cui, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Ma, J. Current status of naturalized alien species in China and its relative problem. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2021, 45, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.M.; Pysek, P.; Rejmanek, M.; Barbour, M.G.; Panetta, F.D.; West, C.J. Naturalization and Invasion of Alien Plants: Concepts and Definitions. Divers. Distrib. 2000, 6, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Fang, G.; Guo, J.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Hu, B. Improved pest and disease spread model for simulating the spread of invasive species: A case study of pine wilt disease. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Febbraro, M.; Bosso, L.; Fasola, M.; Santicchia, F.; Aloise, G.; Lioy, S.; Tricarico, E.; Ruggieri, L.; Bovero, S.; Mori, E.; et al. Different facets of the same niche: Integrating citizen science and scientific survey data to predict biological invasion risk under multiple global change drivers. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 5509–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.h.; Ye, W.h.; Deng, X.; Xu, K. Characteristics of exotic plant invasion and their damages in China. Ecol. Sci. 2002, 21, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Ma, K. Biological invasions:opportunities and challenges facing Chinese ecologists in the era of translational ecology. Biodivers. Sci. 2010, 18, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cao, W. Situation and countermeasure of alien invasive plants in Northeast China. J. Grad. Sch. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2010, 27, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, F.; Han, B.; Bussmann, R.W.; Xue, T.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Chen, T.; Yu, S. Present status, future trends, and control strategies of invasive alien plants in China affected by human activities and climate change. Ecography 2023, 2024, e06919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yan, X.L.; Wang, Z.H.; Li, H.R.; Ma, J.S. Distribution pattern and rating of alien invasive plants in Anhui Province. Plant Sci. J. 2017, 35, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Han, B. Alien invasive species in Inner Mongolia and their influence on the grassland. Pratacultural Sci. 2015, 32, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, C.; Zhang, F. Analysis of socio-economic factors that affected the invasion of alien species in Hebei Province. J. Biosaf. 2021, 30, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.T.; Pan, Y.J.; Chang, C.L.; Liu, Y.J. Effects of native plant-soil microbe interaction on plant invasion. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 48, 1547–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawawa Abonyo, C.R.; Oduor, A.M.O. Artificial night-time lighting and nutrient enrichment synergistically favour the growth of alien ornamental plant species over co-occurring native plants. J. Ecol. 2023, 112, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, H.; Song, X.; Fan, Z. Research progress on the distribution and invasiveness of alien invasive plants in China. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2012, 21, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.H.; He, Z.X.; Gong, Q.; Chen, H.F.; Xing, F.W. The alien plant species in Guangzhou, China. Guihaia 2007, 570–575+554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hierro, J.; Villarreal, D.; Eren, O.; Graham, J.; Callaway, R. Disturbance Facilitates Invasion: The Effects Are Stronger Abroad than at Home. Am. Nat. 2006, 168, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetto, F.; Duncan, R.P.; Hulme, P.E. Environmental gradients shift the direction of the relationship between native and alien plant species richness. Divers. Distrib. 2012, 19, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.A.; Biurrun, I.; García-Mijangos, I.; Loidi, J.; Herrera, M. Assessing the level of plant invasion: A multi-scale approach based on vegetation plots. Plant Biosyst.-Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2013, 147, 1148–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Factors Affecting Alien and Native Plant Species Richness in Temperate Nature Reserves of Northern China. Pol. J. Ecol. 2017, 65, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Shan, L.; Liu, Y. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of invasive alien plants in wetlands of China. Wetl. Sci. 2025, 23, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Yin, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Species composition, floristic characteristics and influencing factors of alien plants in China. Guihaia 2025, 45, 1974–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Bai, F.; Sang, W. Spatial distribution of invasive alien animal and plant species and its influencing factors in China. Plant Sci. J. 2017, 35, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fan, S.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yao, Q. Darwin’s naturalization conundrum:an unsolved paradox in invasion ecology. Sci. Sin. Vitae 2024, 54, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razanajatovo, M.; Föhr, C.; Fischer, M.; Prati, D.; van Kleunen, M. Non-naturalized alien plants receive fewer flower visits than naturalized and native plants in a Swiss botanical garden. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 182, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobock, T.; Winiger, P.; Fischer, M.; van Kleunen, M. The cobblers stick to their lasts: Pollinators prefer native over alien plant species in a multi-species experiment. Biol. Invasions 2013, 15, 2577–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Bao, W.; Wang, A. Influence of Alien species invasion on native biodiversity. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2004, 13, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Yang, J.; Gong, M.; Gong, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y. Niche and interspecific association of dominant species in tree layer of broad-leaved evergreen forests on the western slope of the Cangshan mountain. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2025, 45, 77–88+102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Gan, W.; Wu, Y.; Huang, L. Niche and Interspecific Association of Spontaneous Herbaceous Plants in Fuzhou Section of Minjiang River. J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 2025, 33, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Chen, L.; Tu, H.; Liang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, D.; Nong, J. Niche and interspecific association of main species in shrub layer of Cyclobalanopsis glauca community in karst hills of Guilin, southwest China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 2057–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; van Kleunen, M. Negative conspecific plant-soil feedback on alien plants co-growing with natives is partly mitigated by another alien. Plant Soil 2024, 505, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Shou, H.; Ma, J. The Problem and Status of the Alien Invasive Plants in China. Plant Divers. 2012, 34, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Chen, J.; Yu, S. Biotic homogenization and differentiation of the flora in artificial and near-natural habitats across urban green spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Lin, Y.; Chen, R.; Han, J.; Liu, Y. Road Density Shapes Soil Fungal Community Composition in Urban Road Green Space. Diversity 2025, 17, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.; Chu, Y.; Lee, H. Roads as conduits for alien plant introduction and dispersal: The amplifying role of road construction in Ambrosia trifida dispersal. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhai, C.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, D.; Hu, N.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Y.; Wang, C.; Hong, S.; Hong, W. Spatial pattern of urban forest diversity and its potential drivers in a snow climate city, Northeast China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 94, 128260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-S.; Liang, H.; Song, K.; Da, L.-J. Diversity and classification system of weed community in Harbin City, China. Yingyong Shengtai Xuebao 2014, 33, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Blackburn, T.M.; García-Berthou, E.; Perglová, I.; Rabitsch, W. Displacement and Local Extinction of Native and Endemic Species. In Impact of Biological Invasions on Ecosystem Services; Vilà, M., Hulme, P.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Chen, K.; Da, L.; Gu, H. Diversity, spatial pattern and dynamics vegetation under urbanization in shanghai(III):Flora of the ruderal in the urban area of Shanghai under the influence of rapid urbanization. J. East China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2008, 4, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Statistics and analysis on the seed plant flora in Dashanfeng, Zhejiang. Guihaia 2006, 26, 444–450. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, L.; Cao, E.; Ma, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xu, H. Species of Alien Invasive Asteraceae Plants in China and Their Biological Characteristics. J. Weed Sci. 2025, 43, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.S.; Schwartz, M.W.; Vesk, P.A.; McCarthy, M.A.; Hahs, A.K.; Clemants, S.E.; Corlett, R.T.; Duncan, R.P.; Norton, B.A.; Thompson, K.; et al. A conceptual framework for predicting the effects of urban environments on floras. J. Ecol. 2008, 97, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Zhu, L.; Wang, H.; Nan, Q.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, L. Niche Characteristics of Alien Invasive Plant Erigeron annuus Community in Plain Lake Area. Bot. Res. 2024, 13, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Xu, X.; Jia, G. Urbanization Pressures on Climate Adaptation Capacity of Forest Habitats. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraissinet, M.; Ancillotto, L.; Migliozzi, A.; Capasso, S.; Bosso, L.; Chamberlain, D.E.; Russo, D. Responses of avian assemblages to spatiotemporal landscape dynamics in urban ecosystems. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.T.; Xiao, H.; Fan, C.Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhao, X.H.; Kuang, W.N.; Chen, B.B. Decomposition of β-diversity and its driving factors in shrub communities in Northeast Qinghai Province. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2023, 29, 515–522. [Google Scholar]

- Portela, A.P.; Durance, I.; Vieira, C.; Honrado, J. Environmental filtering and environmental stress shape regional patterns of riparian community assembly and functional diversity. Freshw. Biol. 2023, 68, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, K.; Sakornwimon, W.; Huang, W.; Li, T.; Lai, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, L.; Cong, B.; Liu, S. Spatial planning for dugong conservation: Assessing habitat suitability and conservation gaps in Indo-Pacific Convergence Zone. Mar. Policy 2025, 180, 106777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, S.; Sciandra, C.; Bosso, L.; Russo, D.; Lurz, P.W.W.; Di Febbraro, M. Spatially explicit models as tools for implementing effective management strategies for invasive alien mammals. Mammal Rev. 2020, 50, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosso, L.; Fichera, G.; Mucedda, M.; Pidinchedda, E.; Veith, M.; Smeraldo, S.; De Pasquale, P.P.; Mori, E.; Ancillotto, L. Island Life and Interspecific Dynamics Influence Body Size, Distribution and Ecological Niche of Long-Eared Bats. J. Biogeogr. 2025, e70071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt-Amarante, S.; Abensur, R.; Furet, R.; Ragon, C.; Herrel, A. Do human-induced habitat changes impact the morphology of a common amphibian, Bufo bufo? Urban Ecosyst. 2025, 28, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falfan, I.; MacGregor-Fors, I. Mismatching streetscapes: Woody plant composition across a Neotropical city. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karban, R.; Agrawal, A.A. The Distribution of Species Interactions. Q. Rev. Biol. 2023, 98, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus Type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotypic Genus | Ditypic Genus | Trittypic Genus | Tetratypic Genus | Pentatypic Genus | |

| Genus/Species | 127/127 | 29/58 | 8/24 | 4/16 | 2/10 |

| Percentage (%) | |||||

| Genus proportion | 74.7 | 17.1 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| Species proportion | 54.0 | 24.7 | 10.2 | 6.8 | 4.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, D.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y. Distribution Characteristics and Adaptation Mechanisms of Exotic Spontaneous Plant Diversity in Urban Road Green Spaces of Changchun, China. Plants 2026, 15, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010107

Liu D, Zhao C, Wang Y, Hu Y. Distribution Characteristics and Adaptation Mechanisms of Exotic Spontaneous Plant Diversity in Urban Road Green Spaces of Changchun, China. Plants. 2026; 15(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Diyang, Congcong Zhao, Yongfang Wang, and Yuandong Hu. 2026. "Distribution Characteristics and Adaptation Mechanisms of Exotic Spontaneous Plant Diversity in Urban Road Green Spaces of Changchun, China" Plants 15, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010107

APA StyleLiu, D., Zhao, C., Wang, Y., & Hu, Y. (2026). Distribution Characteristics and Adaptation Mechanisms of Exotic Spontaneous Plant Diversity in Urban Road Green Spaces of Changchun, China. Plants, 15(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010107