1. Introduction

Global climate change is worsening droughts through rising temperatures and reduced rainfall [

1]. Simultaneously, outdated and inefficient irrigation systems in many regions are further aggravating water shortages [

2]. It is estimated that by 2030, at least 20% of developing countries will experience severe water scarcity, posing a substantial threat to global food security and ecosystem stability [

3]. Drought not only endangers food production but also severely impacts traditional Chinese medicinal herbs, which often require specific ecological conditions to thrive [

4,

5]. Among them, the perennial medicinal herb ginseng (

Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) is particularly vulnerable [

6]. The seedling stage is especially critical, as it establishes the foundation for the entire growth cycle [

7]. This phase influences root development, shoot morphology, and subsequent nutrient uptake and utilization, ultimately determining the final yield and quality of ginseng. Therefore, enhancing plant resilience to drought is crucial for promoting green agricultural development and ensuring the stability of medicinal plant production.

Under drought stress, plant cellular homeostasis is significantly perturbed [

8]. The reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as the superoxide anion (O

2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), singlet oxygen (

1O

2), and the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (·OH), are excessively generated [

9]. The excessive accumulation of ROS triggers a cascade of damage to cellular components, including membrane lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, resulting in severe harm to plants and potentially leading to plant mortality [

10]. To mitigate oxidative stress-triggered damage, antioxidants such as vitamins, melatonin, polyphenols, carotenoids, and anthocyanins are commonly employed to scavenge ROS. Nevertheless, the efficacy of such antioxidants remains constrained by their inherent instability and susceptibility to degradation under prevalent environmental factors including illumination, thermal stress, and humidity [

11]. Consequently, it is essential to develop innovative alternatives to address these challenges associated with conventional antioxidants.

The application of nanotechnology has recently shown great potential in improving plant stress tolerance [

12]. Among various nanomaterials, nanozymes are defined by their unique ability to mimic enzymatic functions [

13]. Crucially, nanozymes offer advantages such as stable catalytic activity under extreme conditions, and excellent storage and transport stability, positioning them as superior alternatives to natural enzymes. Metal nanoenzymes (such as ZnO and Fe

3O

4 [

14]) have demonstrated efficacy in scavenging ROS and promoting plant growth. However, their synthesis generally relies on complex, multi-step processes that necessitate organic solvents or harsh chemical reagents, making these methods often incompatible with the principles of green chemistry. Moreover, as single-atom nanozymes [

15], they typically possess high specificity toward a particular ROS, which renders them inadequate for countering the diverse spectrum of ROS generated during cellular oxidative stress and thus limits their effectiveness in mitigating comprehensive oxidative damage. Consequently, the development of novel, green, multifunctional biomimetic antioxidant composites is imperative.

Carbon dots (CDs), as an emerging class of carbon-based nanozymes, exhibit substantial application potential in the fields of biomedicine and agriculture owing to their small size, tunable optical properties and excellent biocompatibility [

16,

17]. In particular, biomass-derived CDs are attracting great interest because they offer an eco-friendly solution [

18]. Previous studies have confirmed that CDs synthesised from biomass sources such as fruit peels inherently possess enzyme-mimetic activity [

19]. As natural reservoirs of antioxidant constituents, traditional Chinese medicinal herbs demonstrate even more distinctive potential for preparing CDs with augmented antioxidant activity [

20]. Epimedium as a classic medicinal herb is abundant in flavonoids and phenolic acid compounds possessing potent antioxidant activity [

21], rendering it an ideal precursor for synthesising antioxidant CDs. Based on this principle, we hypothesise that CDs derived from epimedium possess broad-spectrum ROS scavenging capabilities. Not only can they mimic multi-enzyme activity (specifically superoxide dismutase and catalase, i.e., SOD and CAT), but they can also effectively eliminate other free radicals.

Herein, we synthesized multifunctional antioxidant CDs through a simple one-step hydrothermal method using Epimedium as the carbon source. The CDs demonstrated significant cascade nanozyme activities mimicking both SOD and CAT, as well as potent scavenging abilities against multiple free radicals such as ABTS+· and ·OH. The efficient ROS scavenging capacity of the CDs was demonstrated in vitro and subsequently substantiated in ginseng plants under drought stress. Pot experiments demonstrated that CDs eliminated ROS by modulating antioxidant enzymes and enhancing osmotic regulation in ginseng seedlings. Consequently, it significantly enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, thereby alleviating the drought-induced growth inhibition. Furthermore, transcriptomic analysis revealed that CDs mitigated drought stress by modulating a complex network of genes responsible for enhancing antioxidant defense, photosynthetic efficiency, and stress signaling pathways. The CDs also showed excellent biocompatibility and environmental safety. In conclusion, Epimedium-derived CDs significantly enhanced the drought tolerance of ginseng seedlings, offering a promising strategy to enhance resilience in medicinal plants.

3. Discussion

Due to their excellent physicochemical properties and high biocompatibility, biomass-derived CDs have become highly regarded green and environmentally friendly nanomaterial for boosting plant stress resistance. This study successfully synthesised multifunctional CDs from the medicinal plant Epimedium using a simple one-step hydrothermal method. The as-prepared CDs exhibited uniform dispersion, a small particle size of approximately 6.8 nm, and abundant surface functional groups (such as -OH, -COOH, and -C=O), collectively conferring hydrophilicity. Most studies indicated that biomass-derived CDs primarily consist of C, N, and O elements [

26]. Similarly, FT-IR and XPS analyses identified these three principal elements within the Epimedium-derived CDs. Notably, these CDs exhibited potent cascade nanozyme activity via simultaneously mimicking the characteristics of SOD and CAT for effectively scavenging multiple ROS in a dose-dependent manner. These in vitro antioxidant properties provided a robust foundation for their application in enhancing drought tolerance in ginseng seedlings.

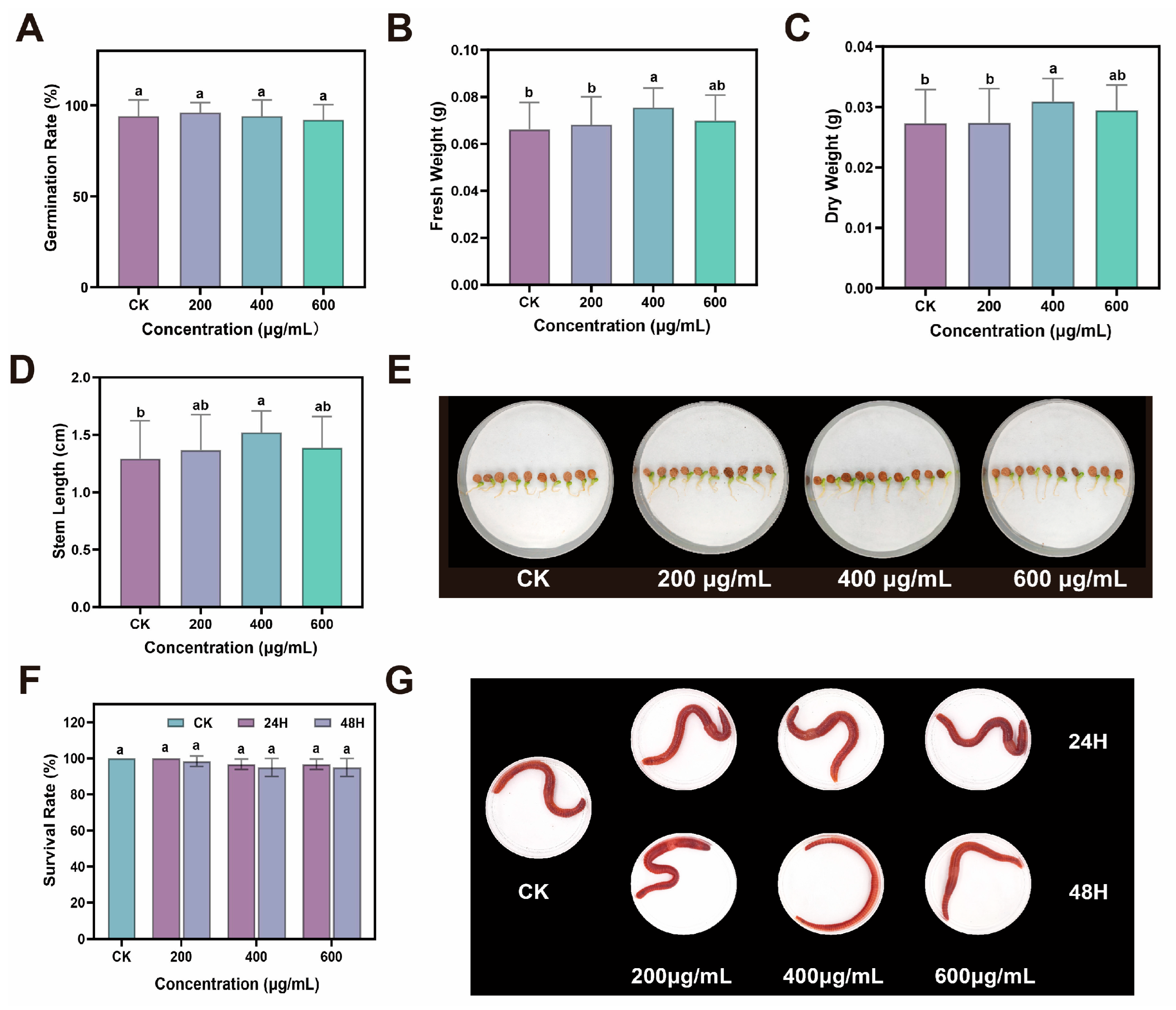

Drought stress severely restricts plant growth by disrupting cellular equilibrium and inducing oxidative damage. Our research demonstrated that foliar application of CDs significantly mitigates drought-induced growth inhibition in ginseng, evidenced by increases in plant height, root length, and biomass, alongside improved photosynthetic performance. Notably, at the optimized concentration of 400 μg/mL, CDs restored net photosynthetic rates and chlorophyll content to levels approaching those of healthy plants, indicating a substantial recovery of photosynthetic function under stress conditions. These findings aligned with prior research demonstrating that CDs enhanced plant photosynthetic capacity and increasing biomass in adverse environments [

27]. Furthermore, CDs significantly reduced the accumulation of ROS and the content of MDA, while concurrently enhancing the activities of key antioxidant enzymes and osmoprotectants. This synergistic enhancement of antioxidant defense and osmotic adjustment underscores the crucial role of CDs in maintaining redox homeostasis and protecting membrane integrity under drought conditions. Similar effects have been documented for CDs derived from

Salvia miltiorrhiza, which were reported not only to scavenge ROS directly but also to mobilize Ca

2+ signaling, thereby enhancing plant adaptation under abiotic stress [

28]. These findings suggested that ROS scavenging represents a common mechanism through which biomass-derived CDs alleviate abiotic stress. Moreover, the regulation of ROS homeostasis is critically dependent on an efficient antioxidant defense system. The enhanced activities of SOD, CAT, and POD, which are essential for ROS scavenging under drought stress, were strongly activated by CDs in drought-stressed ginseng seedlings. Consistent with our observations, the induction of similar antioxidant activities by functional CDs has been reported, which improved plant tolerance under drought conditions through stimulating antioxidant enzymes, modulating osmotic balance, and concomitantly enhancing photosynthetic performance [

29].

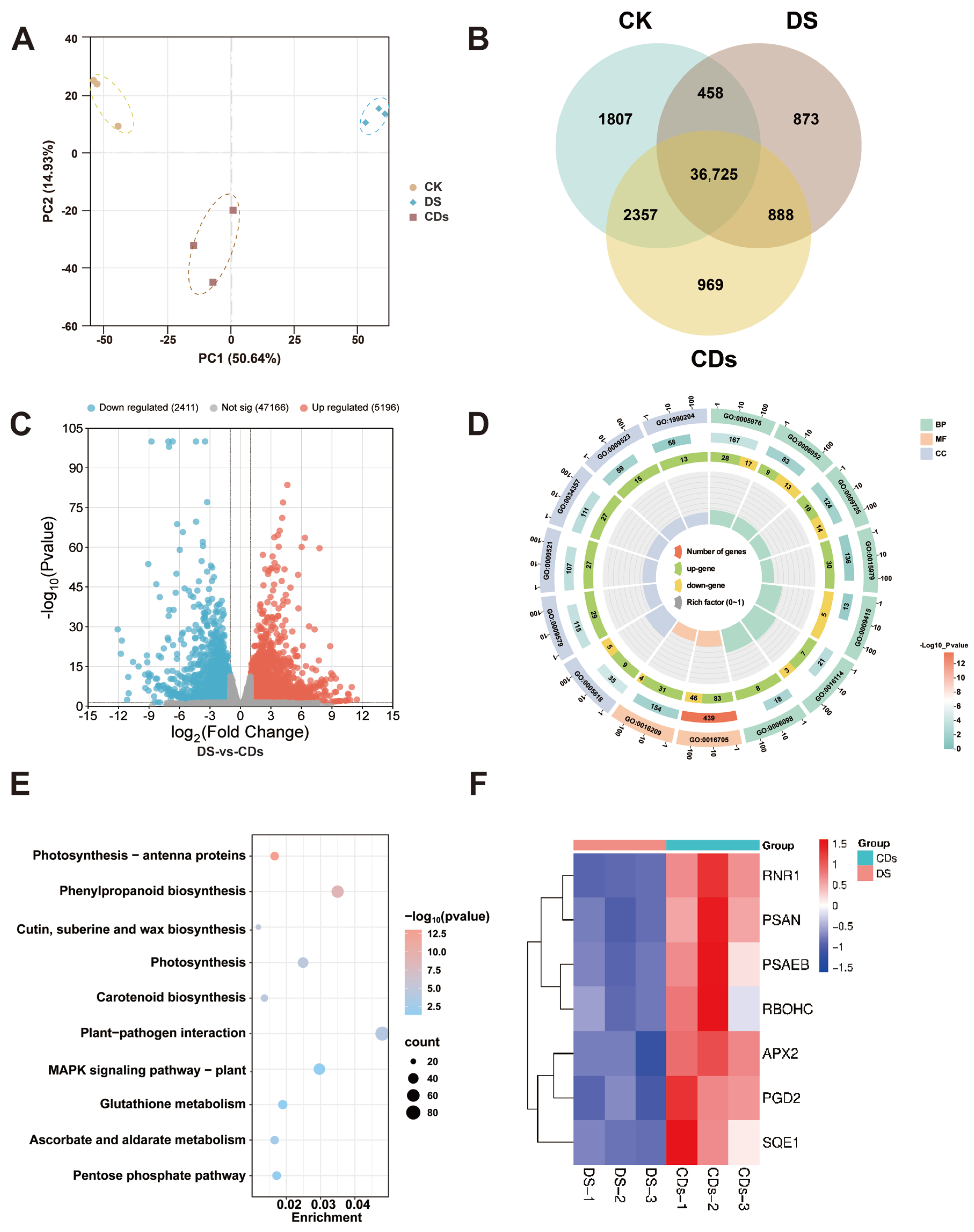

Transcriptome analysis further elucidated the molecular mechanisms underlying CD-induced drought tolerance. Differential gene expression analysis highlighted key alterations in pathways to photosynthesis (e.g.,

PSAEB), antioxidant defence (e.g.,

APX2), MAPK cascade signalling (e.g.,

RBOHC), and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (e.g.,

SQE1), collectively illustrating a multi-level regulatory network activated by CDs. The observed upregulation of the MAPK cascade is of particular significance, as this highly conserved signalling system is a central regulator of plant responses to diverse biotic and abiotic stresses, including drought-induced osmotic stress and ROS signalling [

30]. Within this network, the increased expression of photosynthesis- and antioxidant-related genes, coupled with the coordinated modulation of the MAPK pathway and the downregulation of water-responsive pathways, suggested that CDs facilitate a strategic reallocation of cellular resources from primary growth to defence activation under stress conditions. Furthermore, cytotoxicity assays, seed germination tests, and earthworm toxicity studies confirmed the biosafety and environmental friendliness of

Epimedium-derived CDs. This outcome aligned with the biosafety profiles of other biomass-derived CDs [

31]. Their high safety profile makes them well-suited for use as environmentally friendly agents in agriculture. From a broader perspective, this study not only expands the application of biomass-derived CDs in medicinal plants but also highlights their function as ROS scavengers.

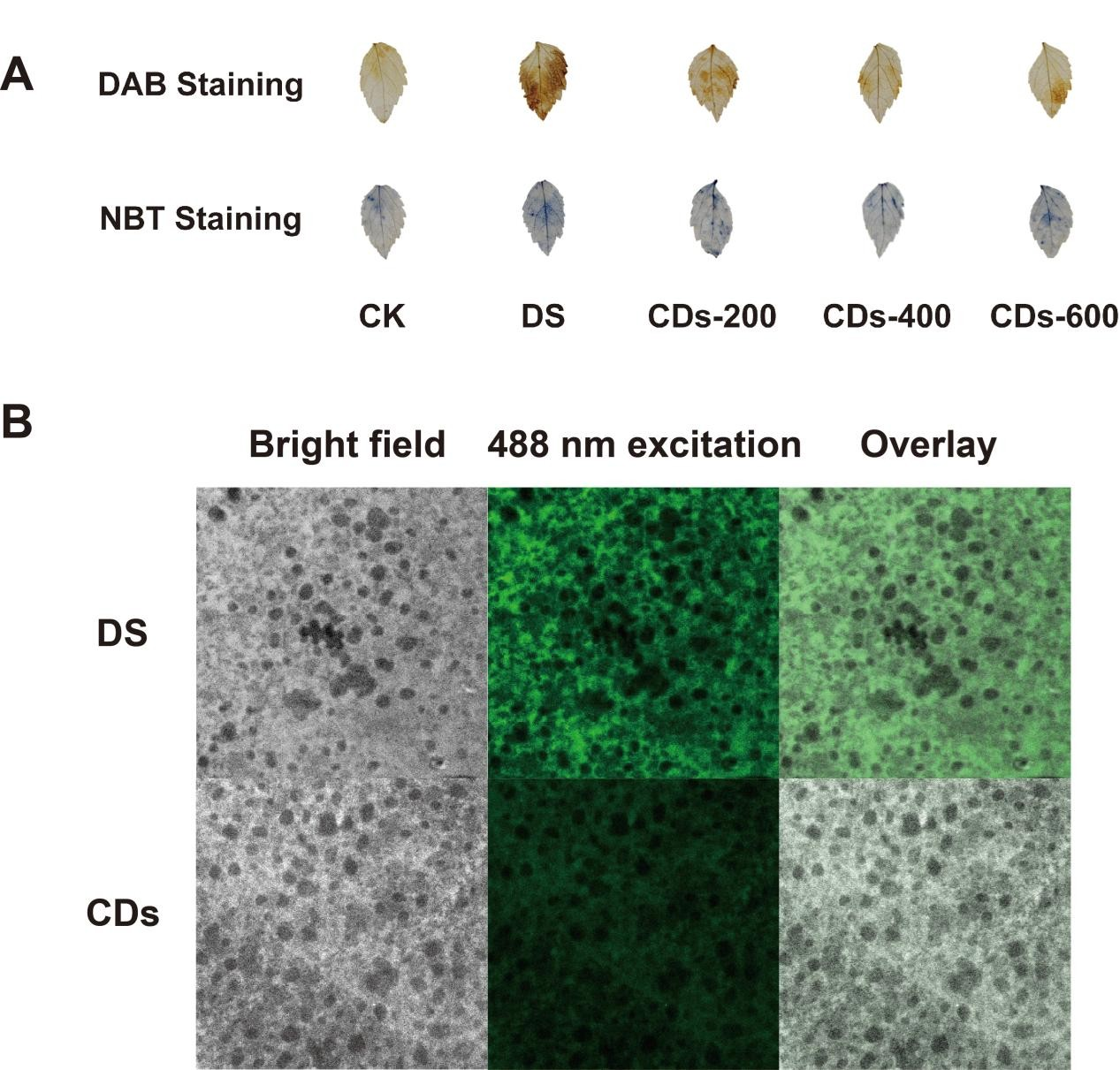

Although we confirmed through integrated physiological, biochemical, and transcriptomic analyses that

Epimedium-derived CDs alleviate drought stress by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activating complex defense signaling networks, we acknowledge that this study failed to directly visualize the distribution and localization of CDs within ginseng tissues. Nevertheless, confocal microscopy using the DCFH-DA probe directly confirmed significantly reduced ROS levels within mesophyll cells treated with carbon dots (

Figure 5B), corroborating the ROS-scavenging activity of carbon dots within plants. This phenomenon aligns with the documented behavior of similarly sized surface-charged carbon dots, which can efficiently penetrate leaf surfaces via stomata and be internalized by plant cells [

32]. Transcriptomic data revealing marked physiological improvements and synergistic transcriptional reprogramming of antioxidant and stress response pathways strongly supports the proposed mechanistic model. Future studies will employ fluorescently labeled CDs or high-resolution microscopy techniques to precisely track the uptake, transport, and localization of these nanoparticles within ginseng plants.

Our findings demonstrated that Epimedium-derived CDs enhanced drought tolerance in ginseng through a coordinated mechanism. This process involved both the direct scavenging of multiple ROS and the activation of the antioxidant enzyme system, which collectively functioned to maintain cellular homeostasis. These insights not only corroborated but also significantly extended previous studies on plant-derived CDs, underscoring the immense potential of Epimedium-derived CDs as a green and environmentally friendly nanomaterial for boosting plant resilience and productivity in drought-stressed environments. Our one-pot hydrothermal process is inherently green, utilizing only deionized water and avoiding toxic solvents or reagents, which significantly lowers its environmental footprint compared to conventional nanomaterial synthesis. Most importantly, the exceptional multi-enzyme mimetic activity of the Epimedium-derived CDs enables them to function effectively at very low concentrations (e.g., 400 μg/mL). This high potency means that a minimal quantity of material is required to treat a large agricultural area. While this research confirmed the effectiveness of Epimedium-derived CDs in improving drought tolerance, several aspects deserve further attention. Future studies should examine the long-term effects of CDs on soil health and microbial communities, track their movement and accumulation in plants over time, and explore possible synergistic effects with other agents. In addition, large-scale field trials will be essential to verify the practical use and sustainability of CDs in real farming environments, facilitating their adoption in climate-resilient agriculture.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was obtained from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All biochemical assay kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Human epidermal keratinocytes (HaCaT) (cell line FH0186) were sourced from Shanghai Fuheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

4.2. Synthesis of CDs

Epimedium was utilized as a carbon source for the synthesis of CDs. Specifically, the raw Epimedium leaves were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h to a constant weight. The dried leaves were subsequently pulverized into a fine powder using a commercial grinder and sieved through a 100-mesh sieve to ensure uniformity. Then, 0.1 g of the powder was dispersed in 4 mL of water. The mixture was sealed in a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and subjected to hydrothermal treatment at 180 °C for 8 h. As the autoclave was cooled to the room temperature, the crude product was dissolved into 4 mL of ultrapure water. Next, the previous solution was centrifuged for 15 min at 8000 rpm to achieve the removal of the undissolved particles, and the supernatant was therewith collected. Finally, the obtained solution was filtered with a 0.22 µm of filter membrane and further purified through the dialysis process (membrane of 1000 MWCO) for 12 h, then stored at 4 °C before use. The yield of the CDs was calculated to be approximately 13.7%, based on the weight of the initial leaf powder and the final collected CDs product.

4.3. Characterization

The morphological characteristics of the specimens were examined using a Tecnai G2 F20 transmission electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA). Quantitative assessment of particle size distribution was performed through statistical analysis of TEM images utilizing ImageJ software (Version 1.8). Chemical functionalization of the nanoparticles was characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) employing a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS20 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, WI, USA). Optical absorption properties were investigated using a Shimadzu UV-1900i ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Surface elemental composition and chemical states were determined through X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements conducted on a Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.4. SOD Mimetic Assays

The SOD-like catalytic activity of CDs was assessed based on the inhibition of nitro-blue tetrazolium (NBT) photoreduction. A reaction mixture was prepared in 400 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4) containing riboflavin (8 μL, 1 mM), NBT (3 μL, 10 mM), L-methionine (26 μL, 0.2 mM), and varying amounts of CDs. This mixture was exposed to UV light for a predetermined duration, after which its absorbance at 560 nm was recorded. A control sample, consisting of the same reaction mixture, was kept in the dark throughout the procedure. All absorbance measurements were performed using a SHIMADZU UV-1900i spectrophotometer. The inhibition rate was calculated according to the following Equation:

where

A0 is the absorbance of the control without CDs,

A1 is the absorbance in the presence of CDs, and

A2 is the absorbance of CDs.

4.5. CAT Mimetic Assays

The CAT-like enzymatic activity of CDs was evaluated through the detection of dissolved oxygen. The assay was performed in 50 mL centrifuge tubes, each containing 35 mL of PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4) and 1 mL of CDs solution at various concentrations. Thereafter, 4 mL of 30% H2O2 solution was introduced into each tube under continuous stirring. Variations in oxygen content within the reaction system were monitored over time using a portable dissolved oxygen meter, with measurements recorded at 2-min intervals for a total of five time points.

4.6. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity of CDs

The hydroxyl radical (·OH) scavenging activity was assayed by the Fenton reaction. First, ·OH was generated based on the reaction of FeSO

4 (9 mM) and H

2O

2 (8.8 mM). After 10 min, SA (9 mM) and various concentrations of CDs were added to the above mixture. After 30 min, the ·OH scavenging percentage was determined by measuring the absorbance of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid at 510 nm, which was generated by the reaction of SA with ·OH. The calculation method is as follows:

where

A0 is the absorbance of the control without CDs,

A1 is the absorbance in the presence of CDs, and

A2 is the absorbance of CDs.

4.7. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity of CDs

The ABTS radical scavenging activity was determined according to the following method. An ABTS

+·cation radical stock solution was generated by reacting ABTS (7.4 mM) with K

2S

2O

8 (2.6 mM). This stock solution was then diluted to a specified concentration to obtain the working solution. Subsequently, CDs at varying concentrations were added to the ABTS working solution. After the mixture was incubated in darkness for 5 min, the absorbance of the resulting solution was measured at 734 nm. The scavenging rate was calculated using the following formula:

where

A0 is the absorbance of the control without CDs,

A1 is the absorbance in the presence of CDs, and

A2 is the absorbance of CDs.

4.8. Plant Growth and Cultivation

Surface-sterilized ginseng seeds were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water. Thirty seeds were sown in each pot (14 cm diameter × 17.2 cm height) filled with soil, and a total of ten pots were set up per treatment group. The resulting seedlings were categorized into five experimental groups: control (CK, 70–75% soil moisture), drought-stressed group (DS, 30–36% soil moisture), and three drought-stressed groups supplemented with CDs at concentrations of 200, 400, and 600 μg/mL. (CDs-200, CDs-400 and CDs-600, 30–36% soil moisture). Following 40 days of cultivation under these conditions, the seedlings were harvested. Various physiological and biochemical indicators were measured.

4.9. Determination of Net Photosynthetic Rate

The net photosynthetic rate of ginseng leaves was determined using LCpro-SD photosynthesizer at 9–11 am in sunny weather with temperature (16–20 °C). Multiple repetitions of the measurements were averaged. Each group underwent ten replicate measurements.

4.10. Measurement of Chlorophyll Content

Different groups of 0.2 g of fresh ginseng leaves were weighed and cryogenically ground. Ethanol was added to each sample, and the homogenate was ground until it turned white, then allowed to stand for 5 min. The homogenate was filtered, concentrated to 25 mL, and the absorbance of the solution was measured at 665 nm, 649 nm, and 470 nm, respectively.

4.11. Determination of Biochemical and Physiological Indexes

The plant height, root length, stem length, fresh weight and dry weight were measured. In addition, the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), proline (PRO), malondialdehyde (MDA), soluble sugar content, and soluble protein content were measured by corresponding reagent kits.

4.12. Determination of Relative Conductivity of Leaves

A 0.5 g sample was accurately weighed, cut into segments, and transferred into a stoppered tube. After adding 10 mL of distilled water, the mixture was agitated on an orbital shaker for 30 min and then allowed to stand for an additional 30 min. The initial conductivity (

C1) was measured using a SANXIN MP521 conductivity meter (Shanghai Sanxin Peirui Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The sample was then heated in a boiling water bath for 30 min, cooled to room temperature, and the final conductivity (

C2) was measured. The relative conductivity was calculated according to the following formula:

where

C1 is the initial conductivity,

C2 is the final conductivity.

4.13. DAB and NBT Staining

A solution of either 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) was prepared by dissolving 50 mg of the respective powder in 100 mL of distilled water, with complete dissolution facilitated by ultrasonication. Leaves from ginseng seedlings were immersed in the staining solution (10 mL) within a six-well plate. The staining process was carried out in the dark under constant agitation at 80–100 rpm. Following an incubation period of 12–16 h, the samples were subjected to decolorization using absolute ethanol in a 95 °C water bath. The ethanol was replaced repeatedly until complete removal of chlorophyll, as indicated by the disappearance of green pigmentation. The decolorized specimens were subsequently mounted and photographed for analysis.

4.14. Intracellular ROS Scavenging Detection

CDs powder was initially dissolved in TES infiltration buffer, with the buffer alone serving as the control. Each solution was slowly injected into separate plant leaves. Following a 3-h incubation period, leaf disks were excised from the infiltrated leaves using a cork borer and subsequently treated with 25 μM H2DCF-DA in the dark. After 30 min of incubation, the leaf disks were rinsed three times with distilled water and gently blotted dry. The prepared samples were mounted on glass slides and carefully sealed with an anti-fade mounting medium to prevent interference from air bubbles. Fluorescence imaging was finally performed using a confocal laser scanning microscope, with signal acquisition conducted under 488 nm laser excitation.

4.15. Biocompatibility and Environmental Safety Evaluation

HaCat cells at the logarithmic growth phase were plated in 96-well plates and maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C for 24 h. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium incorporating varying concentrations of CDs, followed by another 24 h of incubation. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay.

Seed germination phytotoxicity assay. CDs were diluted to three concentrations (200, 400, and 600 μg/mL). Ten milliliters of each solution was added to Petri dishes (Φ = 90 mm) lined with two filter papers. Ten surface-sterilized ginseng seeds were placed in each dish. Plates were incubated in a growth chamber at 25 °C for 14 days, with ultrapure water serving as the control (five replicates per treatment). Germination rates and growth conditions were recorded.

Acute toxicity test of earthworms (filter paper contact test). Prepare multiple porous and breathable earthworm preservation boxes, lay a filter paper in each box, drop different concentrations of CDs aqueous solution (200, 400, 600 μg/mL) onto the filter paper to fully wet it. Then place the earthworm in it. Each box held 20 earthworms, with three replicates per group. After it evaporates, replenish the fluid promptly. All earthworm preservation boxes should be stored in a dark environment at 20 ± 1 °C and 80–85% relative humidity for 24 and 48 h. Record the mortality rate of earthworms and take photos at 24 and 48 h. If earthworms do not respond to mild mechanical stimuli, they are considered dead.

4.16. RNA Sequencing and Transcriptome Analysis

Fresh ginseng leaves were used for transcriptome sequencing, and three biological replicates were taken for each treatment. Total RNA was isolated from plant tissues using the TIANGEN RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (DP441, TIANGEN Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) specifically designed for polysaccharide and polyphenol-rich samples. Approximately 100 mg of tissue was pulverized in liquid nitrogen and vigorously homogenized in Lysis Buffer SL containing β-mercaptoethanol. The homogenate was clarified by centrifugation, and the resultant supernatant was filtered, mixed with absolute ethanol, and applied to the CR3 silica-membrane column. The bound RNA underwent a comprehensive on-column DNase I digestion to remove genomic DNA, followed by sequential washes with Buffer RW1 and Buffer RW. Pure, integral total RNA was finally eluted in RNase-free water. RNA quality was assessed by confirming A260/A280 ratios between 1.8–2.1 and visualizing intact 28S and 18S rRNA bands on a denaturing agarose gel.

The RNA sequencing library was constructed using total RNA as the initial input material. Poly(A) RNA was selectively isolated through hybridization to oligo(dT)-conjugated magnetic beads. The enriched mRNA was subsequently subjected to fragmentation via incubation with divalent cations under elevated temperature in 5× First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer. First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using random hexamer primers and M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNase H−). Second-strand cDNA was then generated through the coordinated action of DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. The resulting double-stranded cDNA fragments were blunt-ended by exonuclease/polymerase treatment, followed by 3′ end adenylation. Adapters featuring a hairpin loop structure were ligated to the prepared fragments. Library fragments within the preferred size range of 370–420 bp were selectively purified using the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Amplification was performed with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase employing Universal PCR primers and Index (X) Primer. The final PCR products were purified using the AMPure XP system, and library quality was verified using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Finally, index-coded samples were clustered on a cBot Cluster Generation system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with the TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the protocols. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated.

4.17. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (Version 27.0.1) software. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All treatments included at least three independent replicates. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In this study, multifunctional antioxidant CDs were successfully synthesized from the medicinal herb Epimedium via a simple one-step hydrothermal method. The CDs exhibited excellent dispersion, small particle size, and abundant surface functional groups. In vitro antioxidant experiments demonstrated that the CDs possessed remarkable cascade nanozyme activities mimicking both SOD and CAT, along with potent free radical scavenging ability. Under drought stress, foliar application of CDs significantly alleviated the inhibition of ginseng seedling growth by drought through regulating the antioxidant enzyme system, improving osmotic balance, and reducing membrane lipid peroxidation. Transcriptomic analysis further revealed that CDs activated key pathways related to photosynthesis, antioxidant defense, and stress signaling, thereby reconstructing a regulatory network. Moreover, safety assessments confirmed the excellent biocompatibility and environmental safety of the CDs. Overall, this work presents a novel, green, and eco-friendly strategy for enhancing drought tolerance in medicinal plants, offering promising prospects for application in environmentally friendly agriculture.