Establishment of a Tissue Culture System for Quercus palustris

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Medium Preparation and Culture Conditions

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Shoot Proliferation Induced by Different Concentrations of 6-BA and KT

2.3.2. Root Induction Induced by Different Concentrations of IBA and NAA

2.3.3. Callus Induction in Q. palustris Induced by Different Combinations of 6-BA and NAA and Various Concentrations of FPX

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sterilization Efficiency of Explants

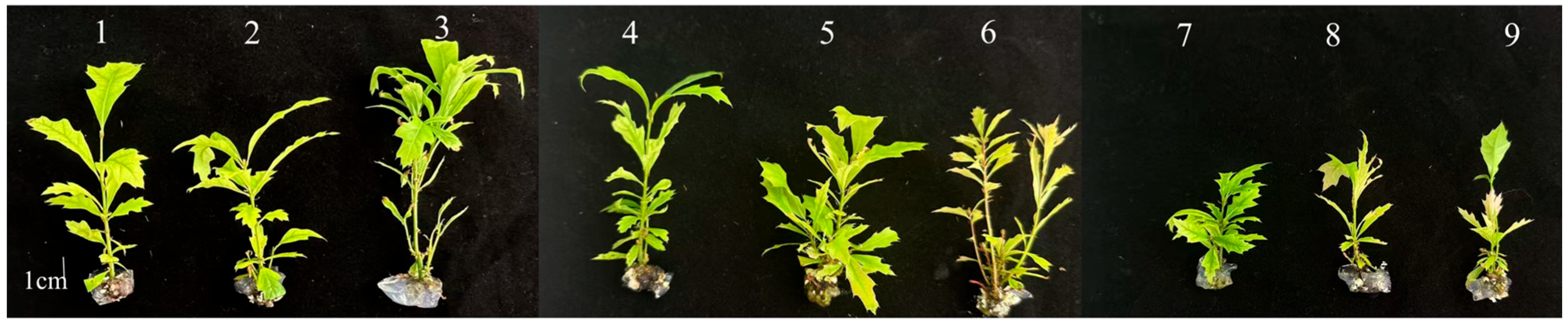

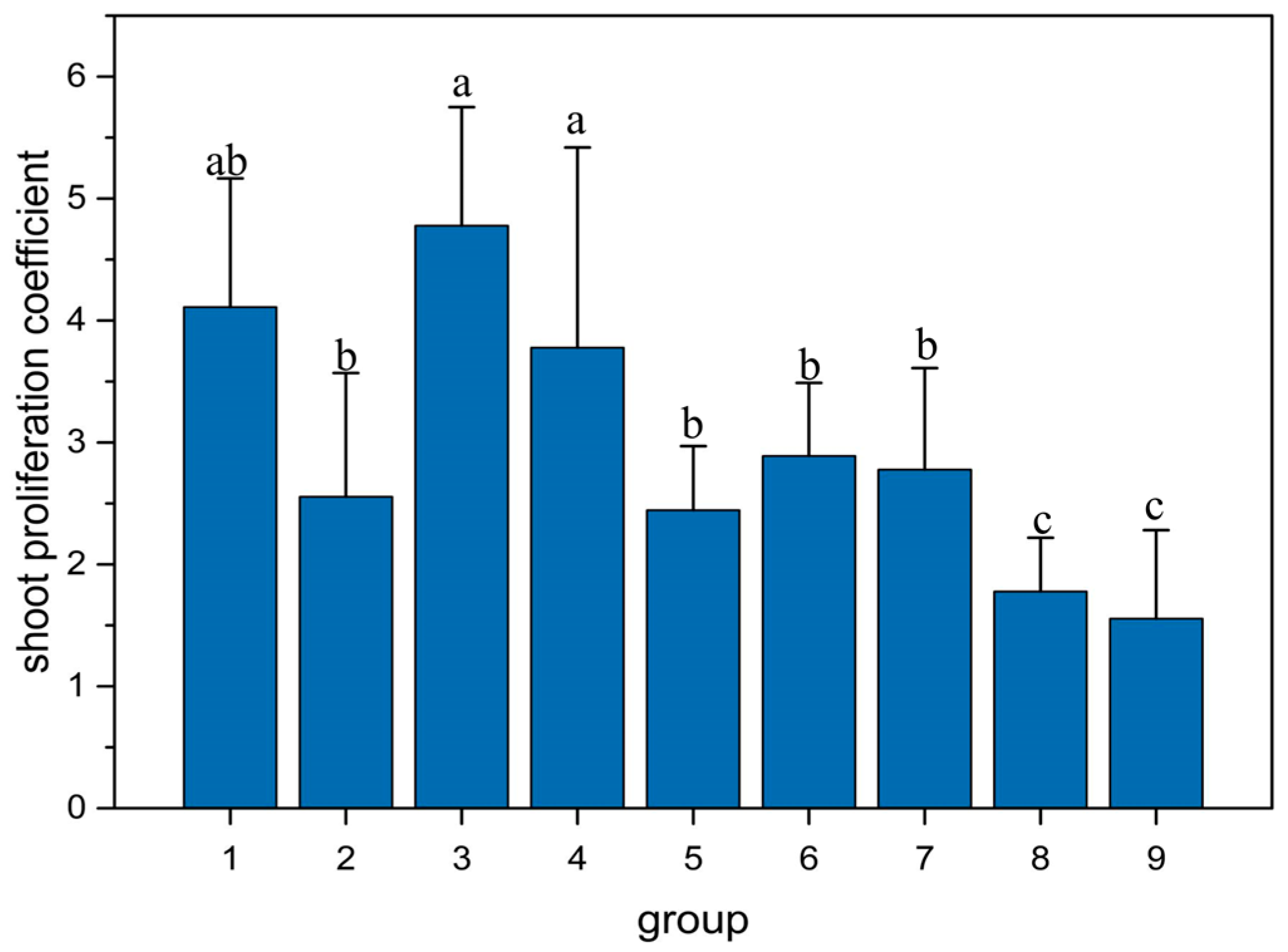

3.2. Effects of Different Combinations of 6-BA and KT Concentrations on Shoot Proliferation in Q. palustris

3.3. Effects of Different Combinations of IBA and NAA Concentrations on Rooting in Q. palustris

3.4. Effects of Different Combinations of 6-BA and NAA Concentrations and FPX on Callus Induction in Q. palustris

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, H.; Cao, Q.; Fan, P.; Yang, N.; Zheng, P.; Wang, R. The effect of climate change on the richness distribution pattern of oaks (Quercus L.) in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.S.; Shifley, S.R.; Rogers, R. Oak-dominated ecosystems. In The Ecology and Silviculture of Oaks; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 8–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brischke, C.; Welzbacher, C.R.; Rapp, A.O.; Augusta, U.; Brandt, K. Comparative studies on the in-ground and above-ground durability of European oak heartwood (Quercus petraea Liebl. and Quercus robur L.). Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2009, 67, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annighöfer, P.; Beckschäfer, P.; Vor, T.; Ammer, C. Regeneration Patterns of European Oak Species (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl., Quercus robur L.) in Dependence of Environment and Neighborhood. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Blas-Morato, R.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I. The Dehesas of Extremadura, Spain: A Potential for Socio-Economic Development Based on Agritourism Activities. Forests 2019, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschendorfer, J.; Rooney, R.; Külheim, C. Strategies to mitigate shifts in red oak (Quercus sect. Lobatae) distribution under a changing climate. Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 2383–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, S.; Reisdorff, C.; Gröngröft, A.; Jensen, K.; Eschenbach, A. Responsiveness of mature oak trees (Quercus robur L.) to soil water dynamics and meteorological constraints in urban environments. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 23, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Liu, G.; Hou, M. The Application of Geographic Information System in Urban Forest Ecological Compensation and Sustainable Development Evaluation. Forests 2024, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, J.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Meng, F.-L. The breeding technology of good hardwood species Mongolian Oak. For. Investig. Des. 2009, 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cernadas, M.J.; Martínez, M.T.; Corredoira, E.; San José, M.d.C. Conservation of holm oak (Quercus ilex) by in vitro culture. Mediterr. Bot. 2018, 39, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Pei, Z.; Street, N.R.; Bhalerao, R.P.; Yu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Ni, J.; et al. Genomic basis of the distinct biosynthesis of β-glucogallin, a biochemical marker for hydrolyzable tannin production, in three oak species. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 2702–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Iqbal, Y.; Sultan, S.; Hassan, M.; Raza, S.; Ali, M.K. Plant tissue culture: A key tool of modern agriculture. Data Plus 2024, 2, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, S.; He, X.; Li, H.; Lyu, S.; Fan, Y. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-Mediated Genetic Transformation and Establishment of CRISPR/Cas9 Genome-Editing Technology in Limonium bicolor. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Huang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, Z.; He, F. Exploration of Suitable Conditions for Shoot Proliferation and Rooting of Quercus robur L. in Plant Tissue Culture Technology. Life 2025, 15, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; Valladares, S.; Vieitez, A.M. Morphohistological analysis of the origin and development of somatic embryos from leaves of mature Quercus robur. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2006, 42, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Magotra, T.; Chourasia, A.; Mittal, D.; Prathap Singh, U.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, S.; García Ramírez, Y.; Dobránszki, J.; Martinez-Montero, M.E. Thin Cell Layer Tissue Culture Technology with Emphasis on Tree Species. Forests 2023, 14, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Cui, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y. Establishment of tissue culture regeneration system of Ficus tikoua. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2024, 60, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, G.; Li, K.; Guo, Y.; Niu, X.; Yin, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Yu, J.; Zheng, S.; et al. Development and Optimization of a Rapid In Vitro Micropropagation System for the Perennial Vegetable Night Lily, Hemerocallis citrina Baroni. Agronomy 2024, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, Y.; Sevindik, B.; Pirhan, A.F. In vitro regeneration protocol for endemic Campanula leblebicii Yıldırım. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2024, 60, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hu, Z.; Luo, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, X.; Wen, S.; Xiao, Z.; Ai, X.; Guo, Y. The Functional Verification of CmSMXL6 from Chrysanthemum in the Regulation of Branching in Arabidopsis thaliana. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Shen, B.; Xie, Y.; Pan, C.; Xu, H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Yin, Z. Regulatory effects and mechanisms of hormones on the growth and rosmarinic acid synthesis in the suspension-cultured cells of Origanum vulgare. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 208, 117824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Castle, W.S.; Gmitter, F.G. In Vitro Shoot Proliferation and Root Induction of Shoot Tip Explants from Mature Male Plants of Casuarina cunninghamiana Miq. HortScience 2010, 45, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Dai, W. Plant regeneration of red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) cultivars ‘Joan J’ and ‘Polana’. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2020, 56, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Yadav, A.; Gupta, R.K.; Sanyal, I. Development of a high-frequency in vitro regeneration system in Indian lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.). Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2024, 60, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, S.; Lan, B.; Gai, Y.; Du, F.K.; Yin, K. Fipexide Rapidly Induces Callus Formation in Medicago sativa by Regulating Small Auxin Upregulated RNA (SAUR) Family Genes. Crops 2025, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, G.C.; Garda, M. Plant tissue culture media and practices: An overview. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2019, 55, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perilli, S.; Moubayidin, L.; Sabatini, S. The molecular basis of cytokinin function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Medina, Y.; Díaz-Ramírez, D.; Herrera-Ubaldo, H.; Di Marzo, M.; Cruz-Valderrama, J.E.; Guerrero-Largo, H.; Ruiz-Cortés, B.E.; Gómez-Felipe, A.; Reyes-Olalde, J.I.; Colombo, L.; et al. The transcription factor ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION 2 orchestrates cytokinin dynamics leading to developmental reprograming and green callus formation. Plant Physiol. 2025, 198, kiaf182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygieł-Sommer, A.; Gaj, M.D. The miR396–GRF Regulatory Module Controls the Embryogenic Response in Arabidopsis via an Auxin-Related Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, G.; Valentim, H.; Costa, A.; Castro, S.; Santos, C. Somatic embryogenesis in leaf callus from a mature Quercus suber L. Tree. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2002, 38, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, M.E.; García-Martín, G.; Antonio Manzanera, J. Shoot development in Quercus suber L. somatic embryos. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2002, 38, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigderrajols, P.; Jofré, A.; Mir, G.; Pla, M.; Verdaguer, D.; Huguet, G.; Molinas, M. Developmentally and stress-induced small heat shock proteins in cork oak somatic embryos. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Casanova-Sáez, R.; Mateo-Bonmatí, E.; Ljung, K. Auxin Metabolism in Plants. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2021, 13, a039867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Huang, R.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Chang, Y.; Pei, D. Transcriptome profiling of indole-3-butyric acid–induced adventitious root formation in softwood cuttings of walnut. Hortic. Plant J. 2024, 10, 1336–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, S.; Singh, S.P.; Kochhar, V.K. Effect of auxins and associated biochemical changes during clonal propagation of the biofuel plant—Jatropha curcas. Biomass Bioenergy 2008, 32, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, R. Optimization of rhizogenesis for in vitro shoot culture of Pinus massoniana Lamb. J. For. Res. 2019, 32, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Khan, B.; Shah, S.T.; Iqbal, J.; Basit, A.; Khan, M.S.; Iqbal, W.; Elsadek, M.F.; Jamal, A.; Ali, M.A.; et al. Preserving Nature’s Treasure: A Journey into the In Vitro Conservation and Micropropagation of the Endangered Medicinal Marvel—Podophyllum hexandrum Royle. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.S.; Degenhardt, J.; Maia, F.R.; Quoirin, M. Micropropagation of Campomanesia xanthocarpa O. Berg (Myrtaceae), a medicinal tree from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Trees 2020, 34, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, L.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Li, P.; Zeng, W.; Kuang, D.; Liu, Q.; et al. The Impacts of Plant Growth Regulators on the Rapid Propagation of Gardenia jasminoides Ellis. in Tissue Culture. Forests 2024, 15, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishal Manchanda, P.; Sidhu, G.S.; Mankoo, R.K. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant potential determination in callus tissue as compared to leaf, stem and root tissue of Carica papaya cv. ‘Red Lady 786’. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazev, A.; Kuluev, B.; Vershinina, Z.; Chemeris, A. Callus Induction and Plant Regeneration from Leaf Segments of Unique Tropical Woody Plant Parasponia andersonii Planch. Plant Tissue Cult. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, S.S.; Woo, H.-A.; Shin, M.J.; Jie, E.Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.-S.; Cho, H.S.; Jeong, W.-J.; Lee, M.-S.; Min, S.R.; et al. Efficient Plant Regeneration System from Leaf Explant Cultures of Daphne genkwa via Somatic Embryogenesis. Plants 2023, 12, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermoshin, A.A.; Kiseleva, I.S.; Galishev, B.A.; Ulitko, M.V. Phenolic Compounds and Biological Activity of Extracts of Calli and Native Licorice Plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 71, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvikrová, M.; Malá, J.; Eder, J.; Hrubcová, M.; Vágner, M. Abscisic acid, polyamines and phenolic acids in sessile oak somatic embryos in relation to their conversion potential. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1998, 36, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, Y.S.; Rhee, J.H.; Chu, H.; Frost, J.M.; Choi, Y. Insights into plant regeneration: Cellular pathways and DNA methylation dynamics. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cai, X. Somatic Embryogenesis Induction and Genetic Stability Assessment of Plants Regenerated from Immature Seeds of Akebia trifoliate (Thunb.). Koidz. Forests 2023, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, B.K.; Islam, M.T.; Muzaffar, A.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Tuskan, G.A.; Chen, J.-G.; Yang, X. Woody Plant Transformation: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Plants 2025, 14, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Tretyakova, I.N.; Nosov, A.M.; Shen, H.; Yang, L. Improved Method for Cryopreservation of Embryogenic Callus of Fraxinus mandshurica Pupr. by Vitrification. Forests 2022, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Group | NaClO Concentration (%) | PPM Concentration (%) | Contamination Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 45.35 |

| 2 | 7.5 | 0.1 | 23.86 |

| 3 | 10 | 0.1 | 17.88 |

| 4 | 5 | 1 | 15.5 |

| 5 | 7.5 | 1 | 12.88 |

| 6 | 10 | 1 | 10.67 |

| 7 | 5 | 2 | 8.64 |

| 8 | 7.5 | 2 | 6.46 |

| 9 | 10 | 2 | 4.21 |

| Treatment No. | 6-BA (mg/L) | KT (mg/L) | Days to Reach 80% Lateral Shoot Initiation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | 0.3 | 0 | 15 |

| a2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 16 |

| a3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 13 |

| a4 | 0.6 | 0 | 15 |

| a5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 16 |

| a6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 15 |

| a7 | 0.9 | 0 | 14 |

| a8 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 15 |

| a9 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 18 |

| Treatment No. | IBA (mg/L) | NAA (mg/L) | Total Number of Roots | Rooting Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 16 | 66.67 |

| b2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 20 | 83.33 |

| b3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 14 | 66.67 |

| b4 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 12 | 50.00 |

| b5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 15 | 62.50 |

| b6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 12 | 57.14 |

| b7 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 10 | 41.67 |

| b8 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 5 | 23.81 |

| b9 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 7 | 33.33 |

| b10 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 6 | 25.00 |

| b11 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 3 | 14.29 |

| b12 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 10 | 41.67 |

| Treatment No. | 6-BA (mg/L) | NAA (mg/L) | FPX (μmol/L) | Number of Surviving Leaves | Number of Leaves with Callus Growth | Induction Rate (%) | Browning Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | - | 29 | 3 | 10.34 | 86.21 |

| c2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | - | 14 | 9 | 64.28 | 42.86 |

| c3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | - | 13 | 7 | 53.85 | 76.92 |

| c4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | - | 35 | 20 | 57.14 | 42.86 |

| c5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | - | 4 | 1 | 25.00 | 100.00 |

| c6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | - | 15 | 10 | 66.67 | 40.00 |

| c7 | 0.6 | 0.1 | - | 43 | 29 | 67.44 | 27.91 |

| c8 | 0.6 | 0.3 | - | 32 | 19 | 59.38 | 43.75 |

| c9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | - | 55 | 26 | 47.27 | 69.09 |

| c10 | 0.8 | 0.1 | - | 44 | 32 | 72.73 | 22.73 |

| c11 | 0.8 | 0.3 | - | 32 | 29 | 90.63 | 34.38 |

| c12 | 0.8 | 0.5 | - | 49 | 34 | 69.38 | 36.73 |

| c13 | - | - | 0 | 13 | 1 | 7.69 | 0.00 |

| c14 | - | - | 10 | 38 | 24 | 63.16 | 21.05 |

| c15 | - | - | 20 | 39 | 2 | 5.13 | 28.21 |

| c16 | - | - | 30 | 35 | 3 | 8.57 | 34.29 |

| c17 | - | - | 40 | 24 | 1 | 4.17 | 58.33 |

| c18 | - | - | 50 | 9 | 1 | 11.11 | 88.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Zhu, P.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.; He, F. Establishment of a Tissue Culture System for Quercus palustris. Plants 2025, 14, 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243870

Wang X, Li H, Chen S, Liu J, Zhu P, Chen X, Xu Z, He F. Establishment of a Tissue Culture System for Quercus palustris. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243870

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xinyi, Hao Li, Silai Chen, Jinyu Liu, Peng Zhu, Xiaohong Chen, Zhenfeng Xu, and Fang He. 2025. "Establishment of a Tissue Culture System for Quercus palustris" Plants 14, no. 24: 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243870

APA StyleWang, X., Li, H., Chen, S., Liu, J., Zhu, P., Chen, X., Xu, Z., & He, F. (2025). Establishment of a Tissue Culture System for Quercus palustris. Plants, 14(24), 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243870