Identification of a Leaf Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Gene BrCER2 in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The gl4 Mutant Shows a Glossy Phenotype

2.2. The Cuticle Permeability of the gl4 Mutant Is Decreased

2.3. Fine Mapping of the Candidate Gene

2.4. Expression Pattern and Subcellular Localization of BrCER2

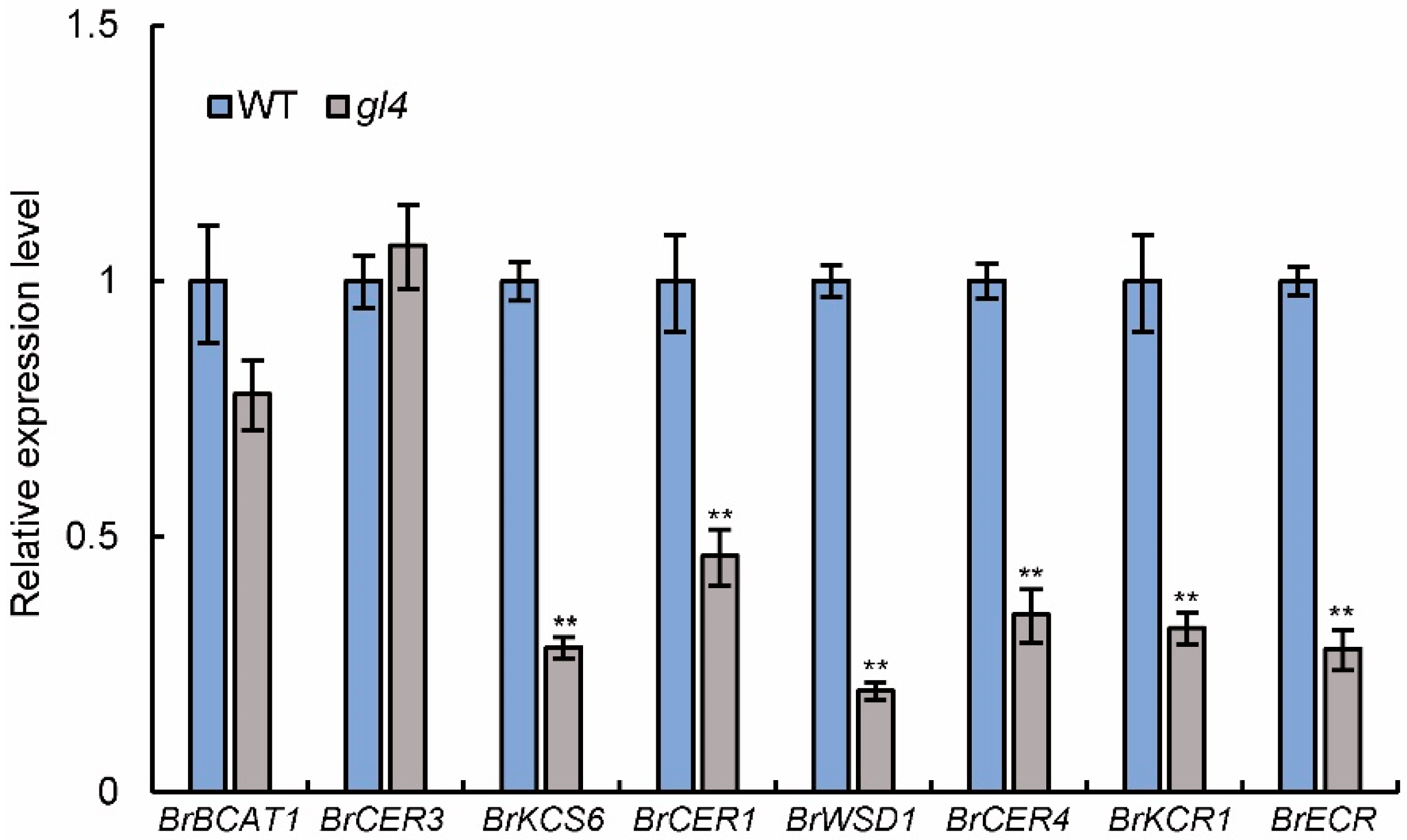

2.5. Expression of Wax-Related Genes Is Down-Regulated in the gl4 Mutant

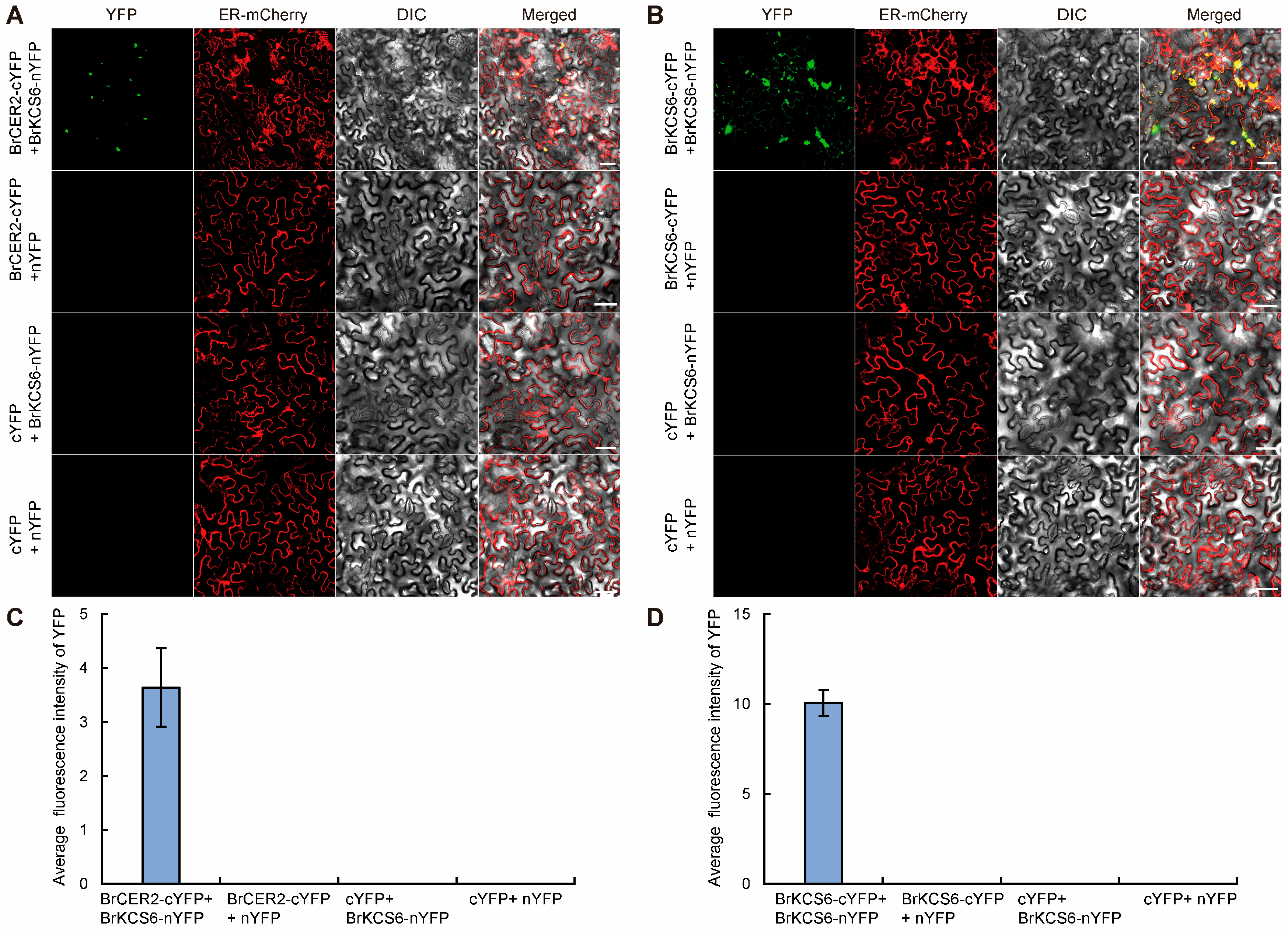

2.6. BrCER2 Interacts with BrKCS6

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

4.3. Toluidine Blue (TB) Test

4.4. Chlorophyll Leaching Assay and Measurement of Water Loss

4.5. BSA-Seq Analysis

4.6. Map-Based Cloning

4.7. DNA, RNA Extraction, and qRT-PCR Analysis

4.8. Subcellular Localization of BrCER2 Protein

4.9. Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation Assays

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, J.; Cao, W.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, P. A 252-bp insertion in BoCER1 is responsible for the glossy phenotype in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). Mol. Breed. 2018, 38, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Zou, J.; Tang, X.; Ren, J.; Song, G.; Feng, H. Mutations in BrMYB31 lead to a glossy phenotype caused by a deficiency in epidermal wax crystals in Chinese cabbage. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2025, 138, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowska, M.; Keyl, A.; Feussner, I. Wax biosynthesis in response to danger: Its regulation upon abiotic and biotic stress. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Advances in the understanding of cuticular waxes in Arabidopsis thaliana and crop species. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Regulatory mechanisms underlying cuticular wax biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventure, G.; Salas, J.J.; Pollard, M.R.; Ohlrogge, J.B. Disruption of the FATB gene in Arabidopsis demonstrates an essential role of saturated fatty acids in plant growth. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1020–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, S.; Song, T.; Kosma, D.K.; Parsons, E.P.; Rowland, O.; Jenks, M.A. Arabidopsis CER8 encodes LONG-CHAIN ACYL-COA SYNTHETASE 1 (LACS1) that has overlapping functions with LACS2 in plant wax and cutin synthesis. Plant J. 2009, 59, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, A.J.; Venegas-Calerón, M.; Vaistij, F.E.; Salas, J.J.; Larson, T.R.; Garcés, R.; Graham, I.A.; Martínez-Force, E. Reduced expression of FatA thioesterases in Arabidopsis affects the oil content and fatty acid composition of the seeds. Planta 2012, 235, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; An, X.; Jiang, Y.; Hou, Q.; Ma, B.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, L.; Wan, X. Plastid-localized ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex ensures maize pollen and anther development through regulating lipid and ROS metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubès, J.; Raffaele, S.; Bourdenx, B.; Garcia, C.; Laroche-Traineau, J.; Moreau, P.; Domergue, F.; Lessire, R. The VLCFA elongase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana: Phylogenetic analysis, 3D modelling and expression profiling. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 67, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, T.M.; Haslam, R.; Thoraval, D.; Pascal, S.; Delude, C.; Domergue, F.; Fernández, A.M.; Beaudoin, F.; Napier, J.A.; Kunst, L.; et al. ECERIFERUM2-LIKE proteins have unique biochemical and physiological functions in very-long-chain fatty acid elongation. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, T.M.; Kunst, L. Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM2-LIKEs are mediators of condensing enzyme function. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 61, 2126–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, E.; Lin, J.; Peng, G.; Huang, J.; Zhu, L.; Deng, L.; Yang, F.; Luo, Q.; et al. HMS1 interacts with HMS1I to regulate very-long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis and the humidity-sensitive genic male sterility in rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 2020, 225, 2077–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, H.; Xiong, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, Z.N. Anther endothecium-derived very-long-chain fatty acids facilitate pollen hydration in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 1101–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Joubès, J. Arabidopsis cuticular waxes: Advances in synthesis, export and regulation. Prog. Lipid Res. 2013, 52, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, M.G.; Keijzer, C.J.; Stiekema, W.J.; Pereira, A. Molecular characterization of the CER1 gene of Arabidopsis involved in epicuticular wax biosynthesis and pollen fertility. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 2115–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, A.; Domergue, F.; Pascal, S.; Jetter, R.; Renne, C.; Faure, J.D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; Lessire, R.; Joubès, J. Reconstitution of plant alkane biosynthesis in yeast demonstrates that Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 and ECERIFERUM3 are core components of a very-long-chain alkane synthesis complex. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3106–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, X.; Lam, P.; Bird, D.; Zheng, H.; Samuels, L.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L. Identification of the wax ester synthase/acyl-coenzyme A: Diacylglycerol acyltransferase WSD1 required for stem wax ester biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, O.; Zheng, H.; Hepworth, S.R.; Lam, P.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L. CER4 encodes an alcohol-forming fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductase involved in cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Yin, M.; Jenks, M.A.; Kosma, D.K.; Yang, P.; Yang, X.; Zhao, H.; Lü, S. Deciphering the core shunt mechanism in Arabidopsis cuticular wax biosynthesis and its role in plant environmental adaptation. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, P.; Tang, J.; Liu, D.; et al. Fine-mapping and analysis of Cgl1, a gene conferring glossy trait in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, D.; Tang, J.; Liu, Z.; Dong, X.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Sun, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Cgl2 plays an essential role in cuticular wax biosynthesis in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Fang, Z.; et al. Fine mapping and candidate gene identification for wax biosynthesis locus, BoWax1 in Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Wei, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, H.; Zhao, X.; Tian, B.; Zhang, X.W.; Yuan, Y. BrWAX2 plays an essential role in cuticular wax biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Liu, C.; Fang, B.; Ren, J.; Feng, H. Identification of an epicuticular wax crystal deficiency gene BrWDM1 in Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris L. ssp. pekinensis). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1161181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Huang, J.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genetic mapping and candidate gene identification of BoGL5, a gene essential for cuticular wax biosynthesis in broccoli. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yue, Z.; Ding, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lei, J.; Zang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Tao, P. A BrLINE1-RUP insertion in BrCER2 alters cuticular wax biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1212528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, Q.; Yang, S.; Feng, H. Fine mapping of BrWax1, a gene controlling cuticular wax biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Mol. Breed. 2013, 32, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Dong, S.; Liu, C.; Zou, J.; Ren, J.; Feng, H. BrKCS6 mutation conferred a bright glossy phenotype to Chinese cabbage. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tang, H.; Wei, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, H.; Niu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X. BrWAX3, encoding a β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase, plays an essential role in cuticular wax biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, X.; Zheng, M.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wu, P.; Jenks, M.A.; Wang, G.; Feng, T.; Liu, L.; et al. An ancestral role for 3-KETOACYL-COA SYNTHASE3 as a negative regulator of plant cuticular wax synthesis. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 2251–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Song, G.; Zou, J.; Ren, J.; Feng, H. BrBCAT1 mutation resulted in deficiency of epicuticular wax crystal in Chinese cabbage. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascal, S.; Bernard, A.; Sorel, M.; Pervent, M.; Vile, D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; Lessire, R.; Domergue, F.; Joubès, J. The Arabidopsis cer26 mutant, like the cer2 mutant, is specifically affected in the very long chain fatty acid elongation process. Plant J. 2013, 73, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Dong, X.; Tian, L.; Qu, L.Q. A β-ketoacyl-coa synthase is involved in rice leaf cuticular wax synthesis and requires a CER2-LIKE protein as a cofactor. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Cao, W.; Tong, L.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Lv, H. Identification and validation of an ECERIFERUM2- LIKE gene controlling cuticular wax biosynthesis in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 4055–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Nikolau, B.J.; Schnable, P.S. Cloning and characterization of CER2, an Arabidopsis gene that affects cuticular wax accumulation. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 1291–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, R.J.; Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Protein-protein interactions in fatty acid elongase complexes are important for very-long-chain fatty acid synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3004–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Feng, T.; Li, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, B.; Zhao, H.; Jenks, M.A.; Yang, P.; Lü, S. Evolutionarily conserved function of the sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.) CER2-LIKE family in very-long-chain fatty acid elongation. Planta 2018, 248, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, Z.; Haslam, T.M.; Kunst, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, H.; Lü, S.; Ma, C. Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase1 influences ECERIFERUM2 activity to mediate the synthesis of very-long-chain fatty acid past C28. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiae253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Gao, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhu, L.; Xu, P.; Yi, B.; Wen, J.; Tu, J.; Ma, C.; et al. A novel dominant glossy mutation causes suppression of wax biosynthesis pathway and deficiency of cuticular wax in Brassica napus. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kosugi, S.; Natsume, S.; Mitsuoka, C.; Uemura, A.; Utsushi, H.; Tamiru, M.; Takuno, S.; et al. QTL-seq: Rapid mapping of quantitative trait loci in rice by whole genome resequencing of DNA from two bulked populations. Plant J. 2013, 74, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waadt, R.; Kudla, J. In planta visualization of protein interactions using bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2008, 2008, pdb.prot4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Bai, X.; Ying, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Huang, M.; Xu, L.; Fang, H.; Wu, J.; Zang, Y. Identification of a Leaf Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Gene BrCER2 in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Plants 2025, 14, 3831. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243831

Huang Y, Bai X, Ying W, Wang Y, Yang C, Huang M, Xu L, Fang H, Wu J, Zang Y. Identification of a Leaf Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Gene BrCER2 in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Plants. 2025; 14(24):3831. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243831

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yunshuai, Xiaoyu Bai, Wenlong Ying, Yanbing Wang, Chaofeng Yang, Mujun Huang, Liai Xu, Huihui Fang, Jianguo Wu, and Yunxiang Zang. 2025. "Identification of a Leaf Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Gene BrCER2 in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis)" Plants 14, no. 24: 3831. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243831

APA StyleHuang, Y., Bai, X., Ying, W., Wang, Y., Yang, C., Huang, M., Xu, L., Fang, H., Wu, J., & Zang, Y. (2025). Identification of a Leaf Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Gene BrCER2 in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Plants, 14(24), 3831. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243831