Azospirillum brasilense as a Bioinoculant to Alleviate the Effects of Salinity on Quinoa Seed Germination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

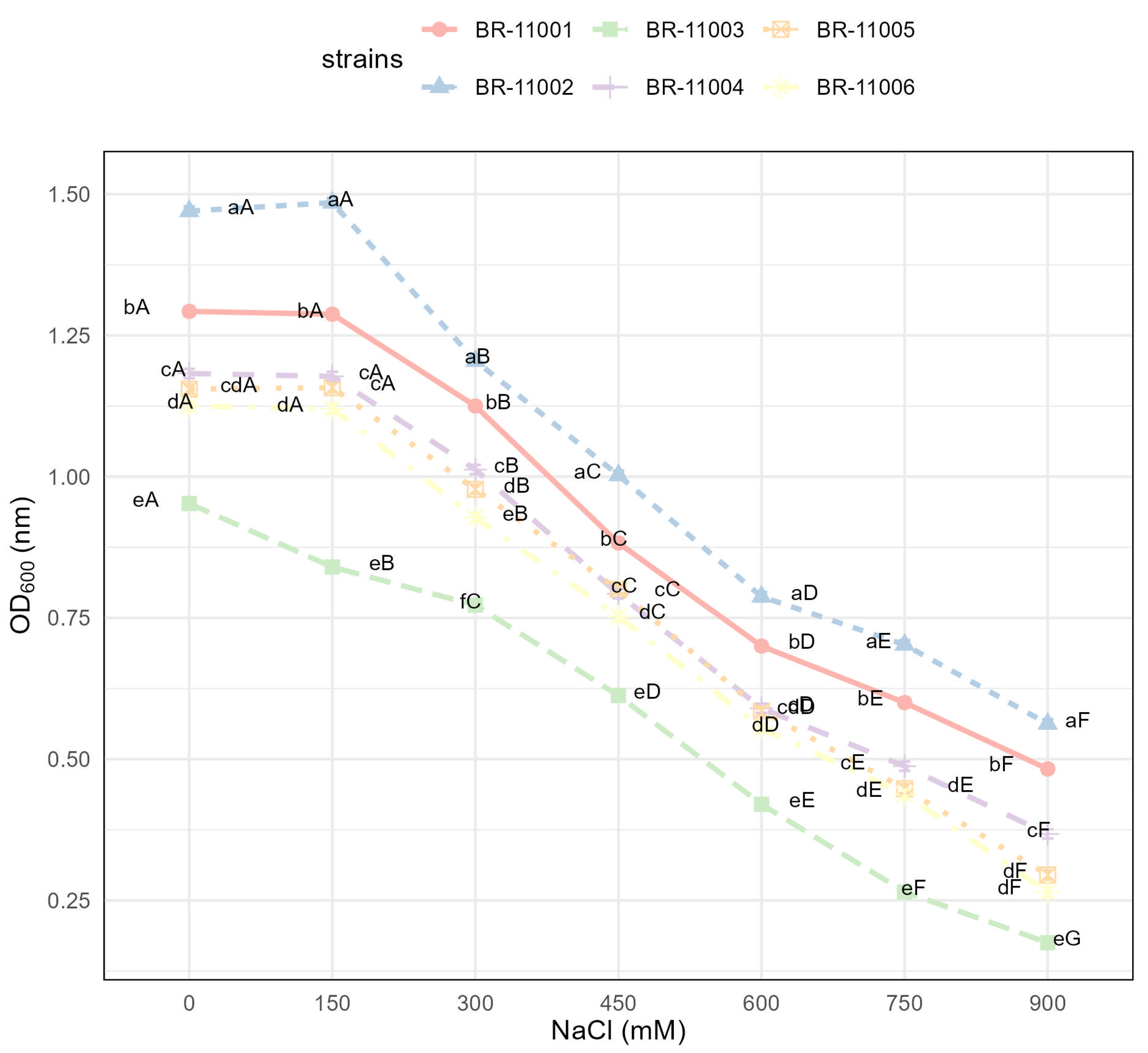

2.1. Bacterial Growth Under Saline and Nonsaline Conditions

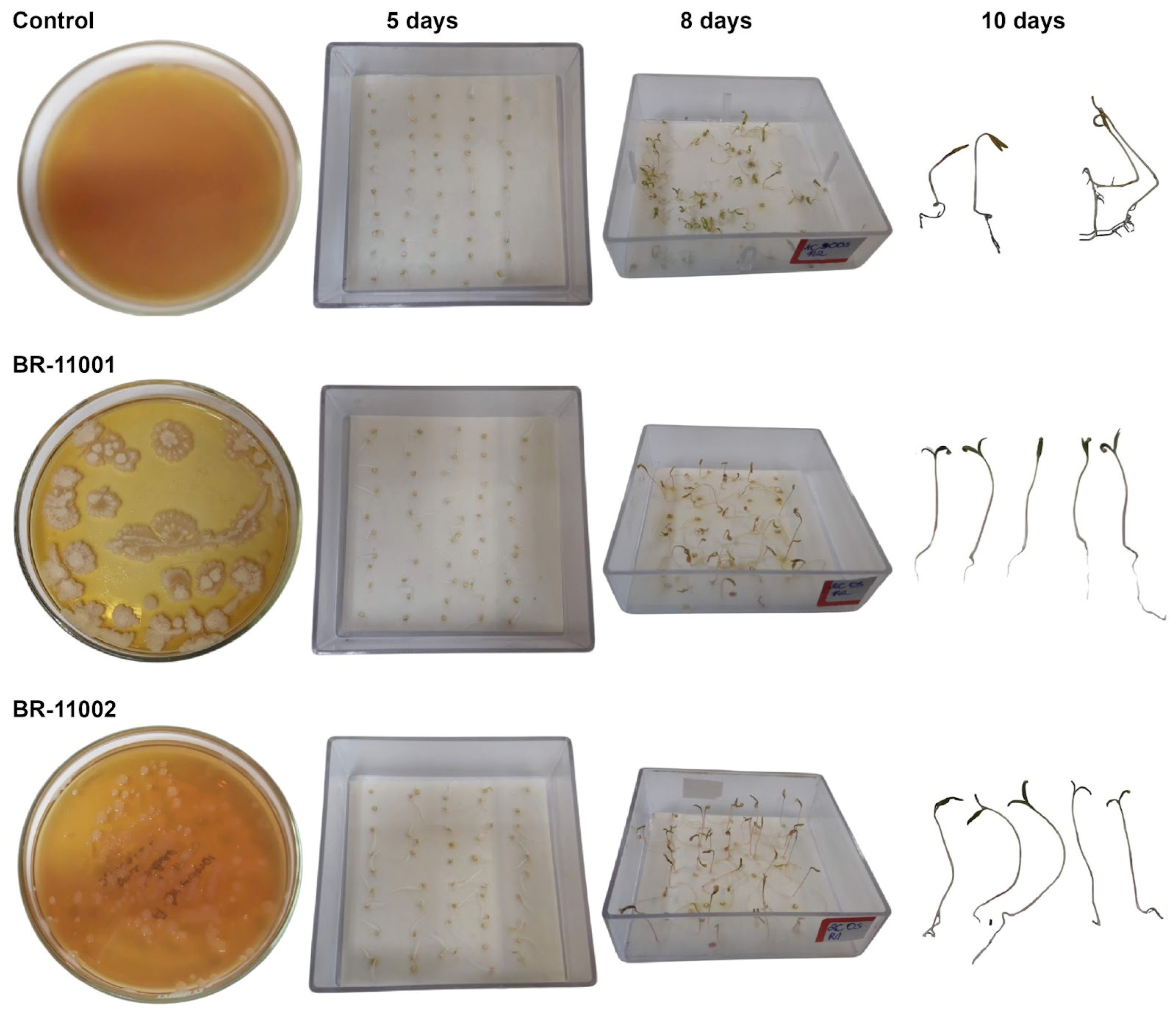

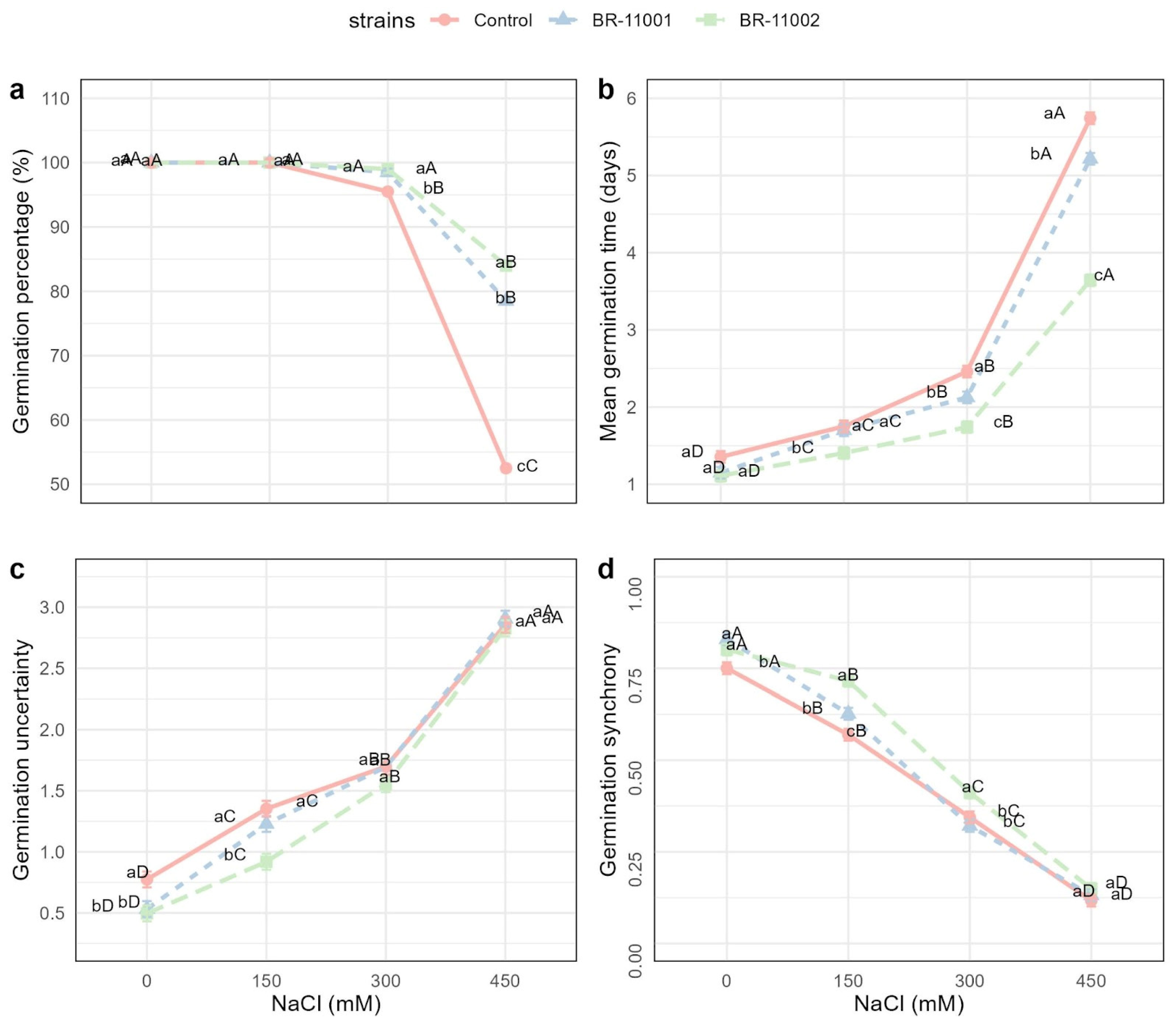

2.2. Germination Dynamics and Cotyledon Emergence Under Salinity Stress

2.3. Seedling Traits and Biomass Allocation

2.4. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Response to Salt Stress and Inoculation

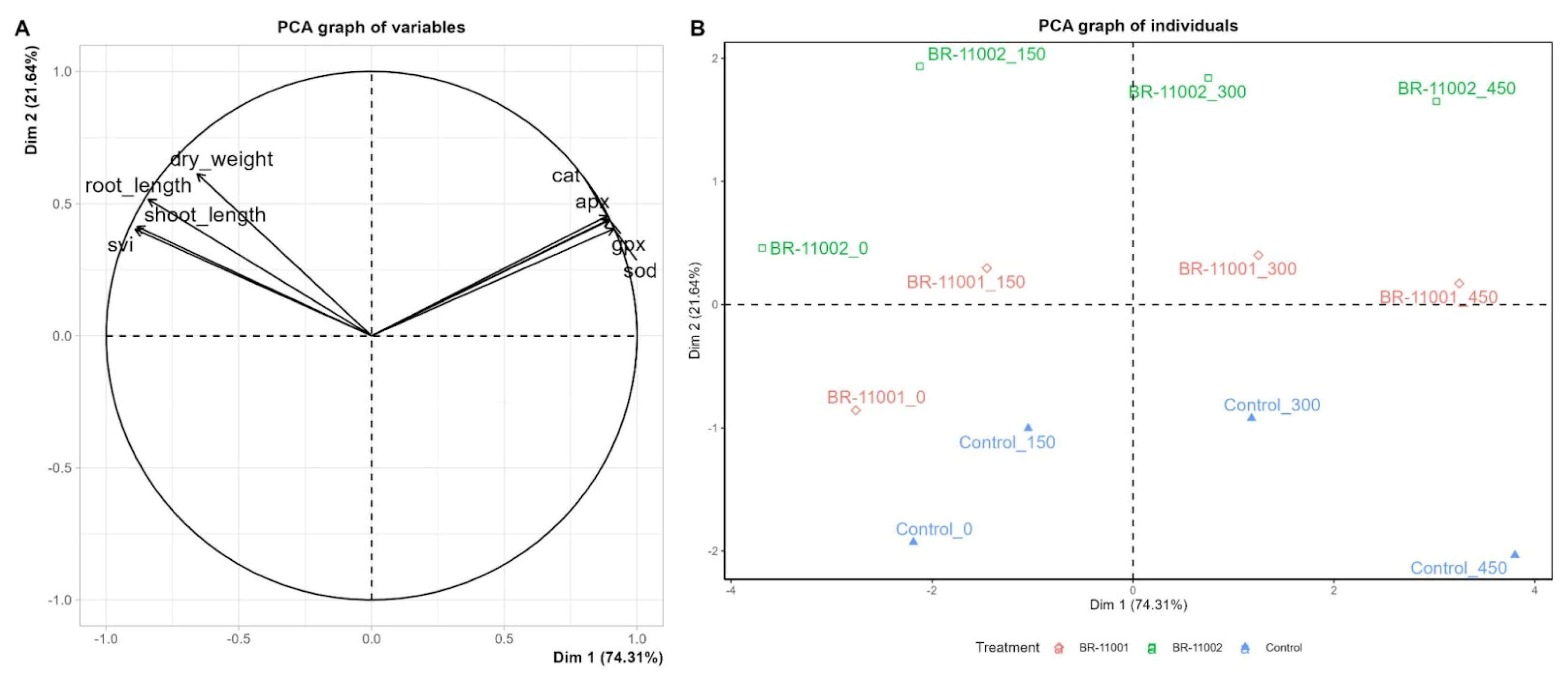

2.5. Multivariate Analysis of Phenotypic and Biochemical Responses Under Salinity Stress

3. Discussion

3.1. Germination Dynamics Under Saline Conditions

3.2. Seedling Responses and Enzyme Activity

3.3. Insights and Limitations

3.4. Implications for Sustainable Agriculture

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biological Materials and Bacterial Strains

4.2. Evaluation of Salinity Tolerance in A. brasilense Strains

4.3. Inoculum Preparation and Seed Treatment

4.4. Germination Assay Under Salinity Stress

4.5. Seedling Growth Evaluation

4.6. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity Assays

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canton, H. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations—FAO. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-00-317990-0. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil Salinity: A Serious Environmental Issue and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria as One of the Tools for Its Alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zörb, C.; Geilfus, C.-M.; Dietz, K.-J. Salinity and Crop Yield. Plant Biol. 2019, 21, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alandia, G.; Rodriguez, J.P.; Jacobsen, S.-E.; Bazile, D.; Condori, B. Global Expansion of Quinoa and Challenges for the Andean Region. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causin, H.F.; Bordón, D.A.E.; Burrieza, H.P. Salinity Tolerance Mechanisms during Germination and Early Seedling Growth in Chenopodium Quinoa Wild. Genotypes with Different Sensitivity to Saline Stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 172, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougiou, N.; Trikka, F.A.; Trantas, E.A.; Ververidis, F.; Makris, A.; Argiriou, A.; Vlachonasios, K.E. Expression of Hydroxytyrosol and Oleuropein Biosynthetic Genes Are Correlated with Metabolite Accumulation during Fruit Development in Olive, Olea europaea, Cv. Koroneiki. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 128, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Wirth, S.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Hashem, A. Phytohormones and Beneficial Microbes: Essential Components for Plants to Balance Stress and Fitness. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Campo, R.J.; Souza, E.M. Inoculation with Selected Strains of Azospirillum brasilense and A. lipoferum Improves Yields of Maize and Wheat in Brazil. Plant Soil 2010, 331, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumairah, F.H.; Setiawati, M.R.; Fitriatin, B.N.; Simarmata, T.; Alfaraj, S.; Ansari, M.J.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Najafi, S. Halotolerant Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Isolated from Saline Soil Improve Nitrogen Fixation and Alleviate Salt Stress in Rice Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 905210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.P.; Belfiore, C.; Úrbez, C.; Ferrando, A.; Blázquez, M.A.; Farías, M.E. Extremophiles as Plant Probiotics to Promote Germination and Alleviate Salt Stress in Soybean. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbab, S.; Silini, A.; Chenari Bouket, A.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Eshelli, M.; El Houda Rabhi, N.; Belbahri, L. Mitigation of NaCl Stress in Wheat by Rhizosphere Engineering Using Salt Habitat Adapted PGPR Halotolerant Bacteria. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, E.T.; Pedrolo, A.M.; Arisi, A.C.M. Thermal and Salt Stress Effects on the Survival of Plant Growth-promoting Bacteria Azospirillum brasilense in Inoculants for Maize Cultivation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 5360–5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.N.A.; Osman, M.E.H.; Kasim, W.A.; Abd El-Daim, I.A. Improvement of Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of Barley Cultivated Under Salt Stress Using Azospirillum brasilense. In Salinity and Water Stress: Improving Crop Efficiency; Ashraf, M., Ozturk, M., Athar, H.R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 133–147. ISBN 978-1-4020-9065-3. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, V.M.; dos Reis, F.B.D., Jr.; Quesada, D.M.; de Oliveira, O.C.A.; Alves, B.J.R.; Urquiaga, S.; Boddey, R.M. Biological Nitrogen Fixation Associated with Tropical Pasture Grasses. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 2001, 28, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degon, Z.; Dixon, S.; Rahmatallah, Y.; Galloway, M.; Gulutzo, S.; Price, H.; Cook, J.; Glazko, G.; Mukherjee, A. Azospirillum brasilense Improves Rice Growth under Salt Stress by Regulating the Expression of Key Genes Involved in Salt Stress Response, Abscisic Acid Signaling, and Nutrient Transport, among Others. Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1216503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Canseco, J.; Bautista-Cruz, A.; Sánchez-Mendoza, S.; Aquino-Bolaños, T.; Sánchez-Medina, P.S. Plant Growth-Promoting Halobacteria and Their Ability to Protect Crops from Abiotic Stress: An Eco-Friendly Alternative for Saline Soils. Agronomy 2022, 12, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, D.; Rokibuzzaman, M.; Khan, A.; Kim, M.C.; Park, H.J.; Yun, D.-J.; Chung, Y.R. Plant-Growth Promoting Bacillus Oryzicola YC7007 Modulates Stress-Response Gene Expression and Provides Protection from Salt Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Amoanimaa-Dede, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Deng, F.; Qin, Y.; Qiu, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, F. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Strain Q1 Inoculation Enhances Salt Tolerance of Barley Seedlings by Maintaining the Photosynthetic Capacity and Intracellular Na+/K+ Homeostasis. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 105, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Bini, A.R.; Barão, L.F.C.; Haliski, A.; Duart, V.M. Seed Inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense and Nitrogen Fertilization for No-till Cereal Production. Agron. J. 2020, 113, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, V.D.S.; Da Silva Brum, M.; Soares, A.B.; Deak, E.A.; Speth, L.A.L.; Martin, T.N. Promoting Black Oat and Ryegrass Growth via Azospirillum brasilense Inoculation after Corn and Soybean Crop Rotation. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2024, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, M.L.T.; Valgas, R.A.; Martins, J.F.d.S. Evaluation of the Agronomic Efficiency of Azospirillum brasilense Strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 in Flood-Irrigated Rice. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra, A.B.C.; de Rezende, A.V.; Florentino, L.A. Co-Inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense Promotes Growth in Forage Legumes. Rev. Ceres 2023, 70, e70514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, T.S.; Schons, D.C.; Ritter, G.; Netto, L.A.; Eberling, T.; Pan, R.; Guimarães, V.F. Growth Promotion by Azospirillum brasilense in the Germination of Rice, Oat, Brachiaria and Quinoa. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2018, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Akhtar, S.S.; Iqbal, S.; Amjad, M.W.; Amjad, M.; Naveed, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Jacobsen, S.-E. Enhancing Salt Tolerance in Quinoa by Halotolerant Bacterial Inoculation. Funct. Plant Biol. 2016, 43, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, M.U.; Raza, M.A.S.; Saleem, M.F.; Waqas, M.; Iqbal, R.; Ahmad, S.; Haider, I. Improving Strategic Growth Stage-Based Drought Tolerance in Quinoa by Rhizobacterial Inoculation. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2020, 51, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade da Silva, M.S.R.; Tavares, O.C.H.; de Oliveira, I.S.R.; de Andrade da Silva, C.S.R.; de Andrade da Silva, C.S.R.; Vidal, M.S.; da Conceição Jesus, E. Stimulatory Effects of Defective and Effective 3-Indoleacetic Acid-Producing Bacterial Strains on Rice in an Advanced Stage of Its Vegetative Cycle. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshat, M.; Abbasi, A.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Sarikhani, M.R.; Chavan, D.D.; Rasoulnia, A. Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (PGPR) Induce Antioxidant Tolerance against Salinity Stress through Biochemical and Physiological Mechanisms. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaepen, S.; Dobbelaere, S.; Croonenborghs, A.; Vanderleyden, J. Effects of Azospirillum brasilense Indole-3-Acetic Acid Production on Inoculated Wheat Plants. Plant Soil 2008, 312, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, M.S.; Ali, H.H.; Iqbal, M.A.; Erinle, K.O.; Javed, T.; Iqbal, J.; Hashmi, M.I.U.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Salama, E.A.A.; Kalaji, H.M.; et al. Cytokinin Production by Azospirillum brasilense Contributes to Increase in Growth, Yield, Antioxidant, and Physiological Systems of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 886041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Raihan, M.R.H.; Masud, A.A.C.; Rahman, K.; Nowroz, F.; Rahman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesawat, M.S.; Satheesh, N.; Kherawat, B.S.; Kumar, A.; Kim, H.-U.; Chung, S.-M.; Kumar, M. Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species during Salt Stress in Plants and Their Crosstalk with Other Signaling Molecules—Current Perspectives and Future Directions. Plants 2023, 12, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, P.; Schnug, E. Reactive Oxygen Species, Antioxidant Responses and Implications from a Microbial Modulation Perspective. Biology 2022, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, M.; Aleem, S.; Sharif, I.; Wu, Z.; Aleem, M.; Tahir, A.; Atif, R.M.; Cheema, H.M.N.; Shakeel, A.; Lei, S.; et al. Characterization of SOD and GPX Gene Families in the Soybeans in Response to Drought and Salinity Stresses. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, W.A.; Shahid, M.; Shafi, Z.; Farah, M.A.; Zeyad, M.T.; Al-Anazi, K.M.; Ahamad, L. Multifaceted Rhizobacterial Co-Inoculation Enhances Drought-Stress Tolerance in Tomato: Insights into Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Responses. J. Basic Microbiol. 2025, 65, e70065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurbekova, Z.; Satkanov, M.; Beisekova, M.; Akbassova, A.; Ualiyeva, R.; Cui, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhangazin, S. Strategies for Achieving High and Sustainable Plant Productivity in Saline Soil Conditions. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Islam, S.; Glick, B.R.; Vimal, S.R.; Bhor, S.A.; Bernardi, M.; Johora, F.T.; Patel, A.; de los Santos Villalobos, S. Elaborating the Multifarious Role of PGPB for Sustainable Food Security under Changing Climate Conditions. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 289, 127895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Quan, R.; Wang, J.; Huang, R.; Qin, H. Salt Stress Promotes Abscisic Acid Accumulation to Affect Cell Proliferation and Expansion of Primary Roots in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.K.; Reddy, K.R.; Li, J. Abscisic Acid and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrand, J.J.; Krieg, N.R.; Döbereiner, J. A Taxonomic Study of the Spirillum lipoferum Group, with Descriptions of a New Genus, Azospirillum Gen. Nov. and Two Species, Azospirillum lipoferum (Beijerinck) Comb. Nov. and Azospirillum brasilense sp. Nov. Can. J. Microbiol. 1978, 24, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, R.M.S.; Campelo, A.P.D.S.; Mackert, A.; Brasil, M.D.S. Desenvolvimento Inicial e Quantificação de Proteínas do Milho após Inoculação Com Novas Estirpes de Azospirillum brasilense. J. Neotrop. Agric. 2019, 6, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadagi, R.S.; Krishnaraj, P.U.; Kulkarni, J.H.; Sa, T. The Effect of Combined Azospirillum Inoculation and Nitrogen Fertilizer on Plant Growth Promotion and Yield Response of the Blanket Flower Gaillardia pulchella. Sci. Hortic. 2004, 100, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira-Longatti, S.M.; Marra, L.M.; Lima Soares, B.; Bomfeti, C.A.; da Silva, K.; Avelar Ferreira, P.A.; de Souza Moreira, F.M. Bacteria Isolated from Soils of the Western Amazon and from Rehabilitated Bauxite-Mining Areas Have Potential as Plant Growth Promoters. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natália dos Santos, N. Taxonomia e reclassificação de estirpes do gênero Azospirillum e Nitrospirillum pertencentes ao Centro de Recursos Biológicos Johanna Döbereiner. Taxonomy and reclassification of strains of the genus Azospirillum and Nitrospirillum belonging to the Johanna Döbereiner Center for Biological Resources. 2022, 102. Available online: https://rima.ufrrj.br/jspui/handle/20.500.14407/20209 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Dos Santos Ferreira, N.; Hayashi Sant’ Anna, F.; Massena Reis, V.; Ambrosini, A.; Gazolla Volpiano, C.; Rothballer, M.; Schwab, S.; Baura, V.A.; Balsanelli, E.; de Pedrosa, F.O.; et al. Genome-Based Reclassification of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 as the Type Strain of Azospirillum baldaniorum Sp. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 6203–6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanovas, E.M.; Barassi, C.A.; Sueldo, R.J. Azospiriflum Inoculation Mitigates Water Stress Effects in Maize Seedlings. Cereal Res. Commun. 2002, 30, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, A.R.; Simoes, W.L.; Salviano, A.M.; Fernandes Junior, P.I.; Barbosa, I.M. Microrganismos Promotores de Crescimento de Plantas Como Mitigadores do Estresse Hídrico e de Nitrogênio em Sorgo Biomassa. 2024. Available online: http://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/alice/handle/doc/1176444 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Martins, S.J.; Rocha, G.A.; de Melo, H.C.; de Castro Georg, R.; Ulhôa, C.J.; de Campos Dianese, É.; Oshiquiri, L.H.; da Cunha, M.G.; da Rocha, M.R.; de Araújo, L.G.; et al. Plant-Associated Bacteria Mitigate Drought Stress in Soybean. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 13676–13686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura Sampaio, V.T. Análise da Composição Centesimal, do Valor Calórico Total da Quinua Real (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd) e seu Perfil de Ácidos Graxos. Rev. Educ. Ung-Ser. 2014, 9, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, G.F.; Stefanello, R.; Menegaes, J.F.; Munareto, J.D.; Nunes, U.R. Seed Germination and Initial Growth of Quinoa Seedlings Under Water and Salt Stress. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.S.; Ferraz, R.L.S.; Dantas-Neto, J.; Martins, V.D.; Viégas, P.R.A.; Meira, K.S.; Ndhlala, A.R.; de Azevedo, C.A.V.; de Melo, A.S. Seed Priming with Light Quality and Cyperus rotundus L. Extract Modulate the Germination and Initial Growth of Moringa Oleifera Lam. Seedlings. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e255836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, G.F.; Alencar, R.S.d.; Viana, P.M.d.O.; Cavalcante, I.E.; Farias, E.S.D.d.; Bonou, S.I.; Sales, J.R.d.S.; Almeida, H.A.d.; Ferraz, R.L.d.S.; Lacerda, C.F.d.; et al. Seed Priming with PEG 6000 and Silicic Acid Enhances Drought Tolerance in Cowpea by Modulating Physiological Responses. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTA. International Rules Seed Testing|Official ISTA Guidelines. Available online: https://www.seedtest.org/en/publications/international-rules-seed-testing.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ranal, M.A.; de Santana, D.G. How and Why to Measure the Germination Process. Braz. J. Bot. 2006, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Isla, F.; Benites-Alfaro, O.E.; Pompelli, M.F. GerminaR: An R Package for Germination Analysis with the Interactive Web Application “GerminaQuant for R.”. Ecol. Res. 2019, 34, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Joo, J.C.; Kim, J.-Y. Evaluation of Heavy Metal Phytotoxicity to Helianthus annuus L. Using Seedling Vigor Index-Soil Model. Chemosphere 2021, 275, 130026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Sinha, R.P.; Häder, D.-P. Methods in Cyanobacterial Research; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-04-002908-4. [Google Scholar]

- Aebi, H. [13] Catalase in Vitro. In Methods in Enzymology; Oxygen Radicals in Biological Systems; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 105, pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rekik, I.; Chaabane, Z.; Missaoui, A.; Bouket, A.C.; Luptakova, L. Effects of Untreated and Treated Wastewater at the Morphological, Physiological and Biochemical Levels on Seed Germination and Development of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench), Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and Fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 326, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, J.J.; Won, J.-H. High-Performance Statistical Computing in the Computing Environments of the 2020s. Stat. Sci. Rev. J. Inst. Math. Stat. 2022, 37, 494–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Isla, F.; Kistner, M.B.; QuipoLab; Inkaverse Inti. Tools and Statistical Procedures in Plant Science. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/inti/index.html (accessed on 8 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Apaza-Calcina, J.D.; Munoz-Salas, M.N.; Lozano-Isla, F.; Rezende, R.P.; Santana Silva, R.J. Azospirillum brasilense as a Bioinoculant to Alleviate the Effects of Salinity on Quinoa Seed Germination. Plants 2025, 14, 3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243829

Apaza-Calcina JD, Munoz-Salas MN, Lozano-Isla F, Rezende RP, Santana Silva RJ. Azospirillum brasilense as a Bioinoculant to Alleviate the Effects of Salinity on Quinoa Seed Germination. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243829

Chicago/Turabian StyleApaza-Calcina, Jose David, Milagros Ninoska Munoz-Salas, Flavio Lozano-Isla, Rachel Passos Rezende, and Raner José Santana Silva. 2025. "Azospirillum brasilense as a Bioinoculant to Alleviate the Effects of Salinity on Quinoa Seed Germination" Plants 14, no. 24: 3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243829

APA StyleApaza-Calcina, J. D., Munoz-Salas, M. N., Lozano-Isla, F., Rezende, R. P., & Santana Silva, R. J. (2025). Azospirillum brasilense as a Bioinoculant to Alleviate the Effects of Salinity on Quinoa Seed Germination. Plants, 14(24), 3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243829