Intraspecific Variation in Drought and Nitrogen-Stress Responses in Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) Half-Sib Progeny

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Leaf Pigment Content

2.2. Relative Water Content (RWC)

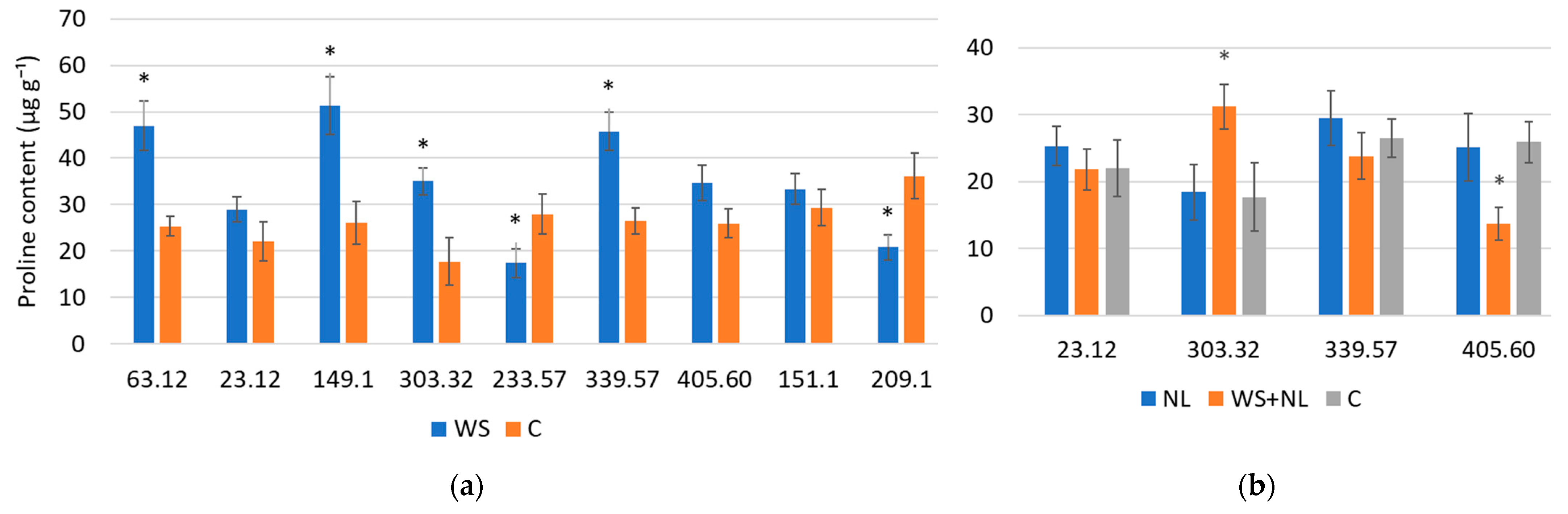

2.3. Proline Content

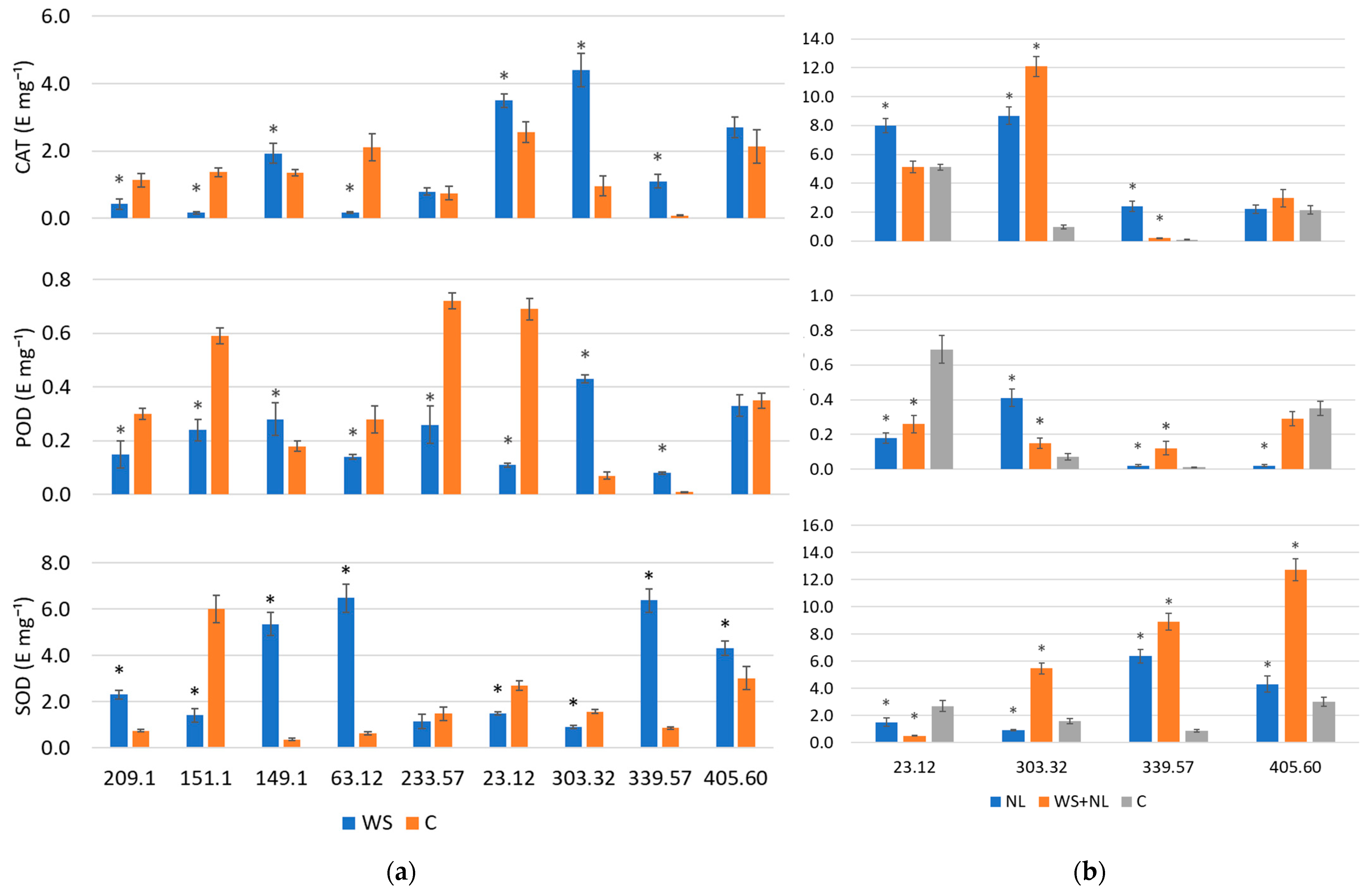

2.4. ROS-Scavenging Enzyme Activity

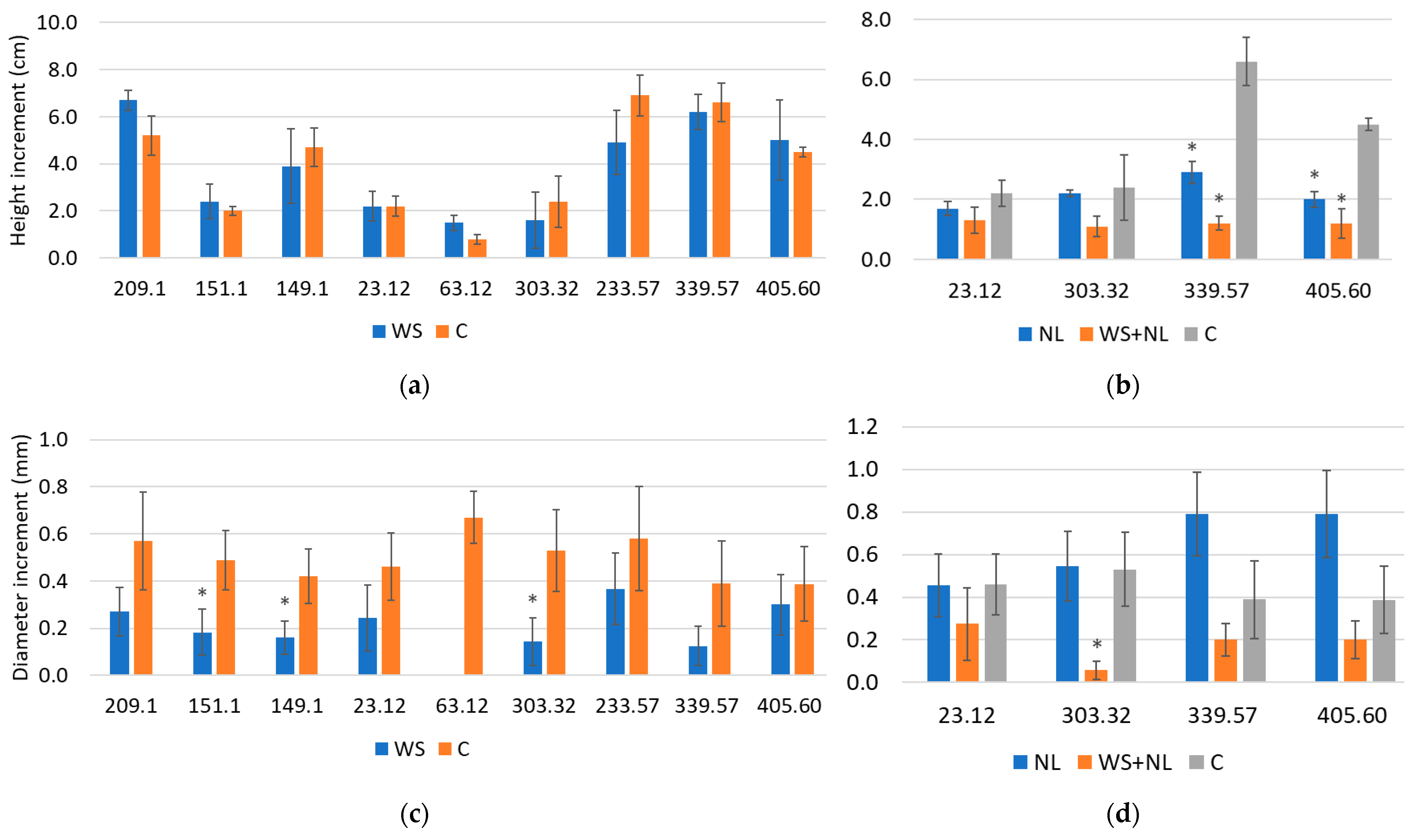

2.5. Plant Height and Diameter

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Half-Sibs F2 Progeny Origin and Plant Material

5.2. Climatic Context

5.3. Edaphic Context

5.4. Controlled Experimental Conditions

5.5. Measurements

5.6. Determination of Soil Water-Holding Capacity

5.7. Water Stress (WS) and Nitrogen Limitation (NL) Treatments

5.8. Enzyme Activity Assays

- dark control: 3 mL reaction medium + 0.2 mL supernatant;

- light control: 3 mL reaction medium + 0.2 mL phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), without supernatant;

- experimental tubes: 3 mL reaction medium + 0.2 mL supernatant.

5.9. Pigment Content Determination

5.10. Relative Water Content (RWC) Assay

5.11. Proline Content Assay

5.12. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Ouyang, S.; Gessler, A.; Wang, X.; Na, R.; He, H.S.; Wu, Z.; Li, M.-H. Root carbon resources determine survival and growth of young trees under long drought in combination with fertilization. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 929855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sever, K.; Bogdan, S.; Škvorc, Ž. Response of photosynthesis, growth, and acorn mass of pedunculate oak to different levels of nitrogen in wet and dry growing seasons. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, E.; Terrer, C.; Pellegrini, A.F.A.; Ahlström, A.; van Lissa, C.J.; Zhao, X.; Xia, N.; Wu, X.; Jackson, R.B. Global patterns of terrestrial nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Meng, X. Tradeoffs of nitrogen investment between leaf resorption and photosynthesis across soil fertility in Quercus mongolica seedlings during the hardening period. J. For. Res. 2024, 35, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Castro, L.; Pardos, M.; Gil, L.; Pardos, J.A. Effects of the interaction between drought and shade on water relations, gas exchange and morphological traits in cork oak (Quercus suber L.) seedlings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 210, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, L. Effects of drought stress and rehydration on physiological and biochemical properties of four oak species in China. Plants 2022, 11, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atar, F.; Yücesan, Z.; Atar, E.; Üçler, A.Ö. Effect of drought stress on physiological and biochemical traits of Quercus petraea subsp. iberica seedlings. Austrian J. For. Sci. 2024, 141, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Xie, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Guo, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, C. Adaptive growth strategies of Quercus dentata to drought and nitrogen enrichment: A physiological and biochemical perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1479563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, K.; Nikbakht, A.; Haghighi, M.; Etemadi, N.; Rahimmalek, M.; Szumny, A. Screening some pine species from North America and dried zones of western Asia for drought stress tolerance in terms of nutrients status, biochemical and physiological characteristics. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1281688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, J.; He, C.; Wang, Q. Effects of light spectra and 15N pulses on growth, leaf morphology, physiology, and internal nitrogen cycling in Quercus variabilis Blume seedlings. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovreškov, L.; Radojčić Redovniković, I.; Limić, I.; Potočić, N.; Seletković, I.; Marušić, M.; Jurinjak Tušek, A.; Jakovljević, T.; Butorac, L. Are foliar nutrition status and indicators of oxidative stress associated with tree defoliation of four Mediterranean forest species? Plants 2022, 11, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vastag, E.; Cocozza, C.; Orlović, S.; Kesić, L.; Kresoja, M.; Stojnić, S. Half-sib lines of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) respond differently to drought through biometrical, anatomical and physiological traits. Forests 2020, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosenko, T.; Schroeder, H.; Zimmer, I.; Buegger, F.; Orgel, F.; Burau, I.; Padmanaban, P.B.S.; Ghirardo, A.; Bracker, R.; Kersten, B.; et al. Patterns of adaptation to drought in Quercus robur Populations in Central European Temperate Forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.; Kjær, E.D.; Hansen, J.K. Adaptive potential of northern pedunculate oak: Genetic variation in growth and phenology for a warmer and drier future. Eur. J. For. Res. 2025, 144, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačurin, M.; Katičić Bogdan, I.; Sever, K.; Bogdan, S. The Effects of Drought Timing on Height Growth and Leaf Phenology in Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.). Forests 2025, 16, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, J.; Hall, M.; Rula, I.; Franzén, M.; Forsman, A.; Sunde, J. Genetic Variation Associated with Leaf Phenology in Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) Implicates Pathogens, Herbivores, and Heat Stress as Selective Drivers. Forests 2025, 16, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzano, A.; Amitrano, C.; Arena, C.; Pannico, A.; Caputo, R.; Merela, M.; Cirillo, C.; De Micco, V. Does Pre-Acclimation Enhance the Tolerance of Quercus ilex and Arbutus unedo Seedlings to Drought? Plants 2025, 14, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J. The global nitrogen-phosphorus imbalance. Science 2022, 375, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnitch, S.; Donovan, T.; Wenz, J.; Flynn, E.; Schipanski, E.; Comas, H. Can Nitrogen Availability Impact Plant Performance under Water Stress? Plant Soil 2025, 511, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Ashraf, M. Proline Alleviates Abiotic Stress Induced Oxidative Stress in Plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 4629–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, M.; Funck, D.; Trovato, M. Proline and ROS: A Unified Mechanism in Plant Development and Stress Response? Plants 2025, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moukhtari, A.; Cabassa-Hourton, C.; Farissi, M.; Savouré, A. How Does Proline Treatment Promote Salt Stress Tolerance During Crop Plant Development? Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourado, P.; de Souza, E.; dos Santos, M.; Lins, C.; Monteiro, D.; Paulino, M.; Schaffer, B. Stomatal Regulation and Osmotic Adjustment in Sorghum in Response to Salinity. Agriculture 2022, 12, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budeanu, M.; Apostol, E.N.; Besliu, E.; Crișan, V.E.; Petritan, A.M. Phenotypic Variability and Differences in the Drought Response of Norway Spruce Pendula and Pyramidalis Half Sib Families. Forests 2021, 12, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lankhost, J.A.; Stomph, T.J.; Schneider, H.M.; Chen, Y.; Mi, G.; Yuan, L.; Evers, J.B. Root Plasticity Improves Maize Nitrogen Use When Nitrogen Is Limiting: An Analysis Using 3D Plant Modelling. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 5989–6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Whalen, J. Plasticity of Maize (Zea mays L.) Roots in Water Deficient and Nitrogen Limited Soil. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Quan, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, C.; Yu, J.; Tang, X.; Wu, P.; Ma, X.; Yan, X. Integrated Morphological and Physiological Plasticity of Roots for Improved Seedling Growth in Cunninghamia lanceolata and Schima superba under Nitrogen Deficiency and Different NH4+:NO3− Ratios. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1673572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Li, S.; Cui, H.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Hao, G. Divergence in Leaf and Cambium Phenologies among Temperate Tree Species with Reference to Xylem Hydraulics. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1562873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzano, A.; Merela, M.; Krže, L.; Čufar, K. Xylogenesis under Climatic Stress: Wood Anatomical Evidence of Harsh Conditions. Les/Wood 2025, 74, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.; Doonan, J.; Hansen, J.; Kosawang, C.; Xu, J.; Olofsson, J.; Kjær, E. Genomic Selection for Accelerated Heartwood Formation in Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. bioRxiv, 2025; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.; Alwasel, S.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: Antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudenko, N.; Vetoshkina, D.; Marenkova, T.; Borisova-Mubarakshina, M. Antioxidants of Non-Enzymatic Nature: Their Function in Higher Plant Cells and the Ways of Boosting Their Biosynthesis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanović, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Natić, M.; Kuča, K.; Jaćević, V. The Significance of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: A Concise Overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 552969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnoff, N.; Wheeler, G.L. The ascorbate biosynthesis pathway in plants is known, but there is a way to go with understanding control and functions. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2604–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Nesi, A.; Araújo, W.L.; Zsögön, A. Plant stress physiology: Safeguarding food security in a changing climate. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 4731–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Tan, B.; Ochir, A.; Chong, P. Integrated physiological, transcriptomic, and metabolomic analyses elucidate the mechanism of salt tolerance in Reaumuria soongorica mediated by exogenous H2S. BMC Plant Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Rivas-Saenz, S.; Penas, Á. Worldwide Bioclimatic Classification System; Backhuys Publishers: Kerkwerve, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- WeatherSpark. Historical Weather During 2025. Available online: https://weatherspark.com/y/101437/Average-Weather-in-Semiluki-Russia-Year-Round (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Brischke, C.; Wegener, F.L. Impact of Water Holding Capacity and Moisture Content of Soil Substrates on the Moisture Content of Wood in Terrestrial Microcosms. Forests 2019, 10, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganeli, B.; Batalha, M.A. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus availability on the early growth of two congeneric pairs of savanna and forest species. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, e235573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbary, M.A.; Læssøe, S.B.; Novikov, A.; Ræbild, A.; Rosendal Jensen, M.; Fomsgaard, I. Drought effects on growth, physiology, and biochemistry of oak seedlings depend on provenance. Physiol. Plant. 2020, 168, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAdam, J.W.; Sharp, R.E.; Nelson, C.J. Peroxidase activity in the leaf elongation zone of tall fescue: II. Spatial distribution of apoplastic peroxidase activity in genotypes differing in length of the elongation zone. Plant Physiol. 1992, 99, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, L. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, O.; Rosebrough, N.; Farr, A.; Randall, R. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.R. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1983, 11, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrs, H.D.; Weatherley, P.E. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 1962, 15, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbary, E.; Fathizadeh, O.; Pazhouhan, I.; Zarafshar, M.; Tabari, M.; Jafarnia, S.; Parad, G.A.; Bader, M.K.-F. Drought and Pathogen Effects on Survival, Leaf Physiology, Oxidative Damage, and Defense in Two Middle Eastern Oak Species. Forests 2021, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tree No. (by Location) | Tree No. (State Register) | Location, Block | Height, m | Diameter, cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19.1 | 57 | 34.5 | 66.5 |

| 12 | 25.12 | 57 | 34.5 | 52.0 |

| 32 | – | 35 | 34.5 | 50.0 |

| 57 | 165.60 | 33 | 33.5 | 60.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grodetskaya, T.A.; Popova, A.A.; Ryzhkova, V.S.; Trapeznikova, E.I.; Evlakov, P.M.; Lebedev, V.G.; Shestibratov, K.A.; Krutovsky, K.V. Intraspecific Variation in Drought and Nitrogen-Stress Responses in Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) Half-Sib Progeny. Plants 2025, 14, 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243814

Grodetskaya TA, Popova AA, Ryzhkova VS, Trapeznikova EI, Evlakov PM, Lebedev VG, Shestibratov KA, Krutovsky KV. Intraspecific Variation in Drought and Nitrogen-Stress Responses in Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) Half-Sib Progeny. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243814

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrodetskaya, Tatiana A., Anna A. Popova, Vladlena S. Ryzhkova, Ekaterina I. Trapeznikova, Petr M. Evlakov, Vadim G. Lebedev, Konstantin A. Shestibratov, and Konstantin V. Krutovsky. 2025. "Intraspecific Variation in Drought and Nitrogen-Stress Responses in Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) Half-Sib Progeny" Plants 14, no. 24: 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243814

APA StyleGrodetskaya, T. A., Popova, A. A., Ryzhkova, V. S., Trapeznikova, E. I., Evlakov, P. M., Lebedev, V. G., Shestibratov, K. A., & Krutovsky, K. V. (2025). Intraspecific Variation in Drought and Nitrogen-Stress Responses in Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) Half-Sib Progeny. Plants, 14(24), 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243814